Abstract

Purpose

Rectal prolapse commonly affects elderly, frail patients. The impact of frailty alone on surgical outcomes for rectal prolapse has not been thoroughly investigated. The aim of this study was to utilize the National Inpatient Sample and the modified frailty index (mFI-11) to compare postoperative outcomes between frail and robust patients undergoing surgery for rectal prolapse.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective population-based cohort study using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) NIS from 2015 to 2019. The mFI-11 was utilized to classify patients as frail or robust. The primary outcomes were overall in-hospital postoperative morbidity and mortality. The secondary outcomes included system-specific postoperative morbidity, length of stay (LOS), total in-hospital healthcare cost, and discharge disposition. These were assessed using univariable and multivariable regressions.

Results

A total of 2130 patients, 239 frail (mFI > 0.27) and 1,891 robust patients (mFI < 0.27) who underwent rectal prolapse repair were analyzed. After adjustment, frail patients had a higher rate of in-hospital mortality (OR 10.38, 95% CI 0.65–166.59, p = 0.098) and morbidity (OR 2.18, 95% CI 1.31–3.63, p = 0.003), longer LOS (MD 1.60 days, 95% CI 1.05–2.44, p = 0.028), and greater cost of treatment (MD $15,561.56, 95% CI − 6023.12–37,146.25, p = 0.157) than robust patients.

Conclusion

Frailty increases postoperative morbidity and mortality and cost more to the healthcare system overall for patients undergoing rectal prolapse repair. This retrospective study is limited by selection bias and residual confounding. Consideration of preoperative optimization programs for frail patients undergoing surgery for rectal prolapse is an important next step to mitigate these poor outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Rectal prolapse is a debilitating pathology that can lead to significant dysfunctional defecation with a resultant negative impact on quality of life [1]. Given that rectal prolapse occurs due to anatomical abnormalities, namely a patulous anus, levator diastasis, a deep pelvic cul-de-sac, a redundant sigmoid colon, and loose sacral fixation of the colon, that worsen with age, this is a disease that is predominantly seen in elderly patients [1]. Patients over the age of 65 are two times more likely to experience rectal prolapse than those younger than 65 years of age [2]. Surgical management of rectal prolapse has changed significantly over the past two decades [3]. In an epidemiological study from England analysing trends in rectal prolapse management from 2001 to 2012, authors showed a dramatic increase in rectal prolapse surgery with introduction of laparoscopic approaches [3]. Operative intervention may involve either an abdominal or a perineal approach [1].

As per the 2017 Dutch guidelines on management of rectal prolapse, external rectal prolapse requires surgical management whereas surgery for internal rectal prolapse is considered if a patient fails conservative treatment [4]. Laparoscopic ventral rectopexy is the recommended first-line surgical treatment for both external and internal rectal prolapse. Perineal approaches include Delorme or Altemeier procedure, with no difference in recurrence rates between the two procedures [4]. The PROSPER trial randomized patients with rectal prolapse to different surgical approaches and showed that patients with recurrence had a significantly worse quality of life [5]. While perineal approaches are associated with higher rates of recurrence, they are often preferred in older patients as they have an associated lower risk of postoperative morbidity (~ 20%) as compared to abdominal approaches (~ 50%) [6]. The Consensus Statement of Italian Colorectal Surgery group provide similar recommendations for treatment as the Dutch guidelines and suggests that perineal approach should be considered only when abdominal approach could not be undertaken due to anesthetic risks [7].

Elderly patients undergoing operative intervention for their rectal prolapse are often frail due to the physiologic decline that occurs with age [8]. Yet, the impact of frailty, independent of age, has not been studied in the setting of rectal prolapse. Although there are no studies discussing impact of frailty on rectal prolapse surgery, frailty has shown worse outcomes in other forms of colorectal surgery [8, 9]. A prospective cohort study of over five thousand males over 65 years of age showed mortality was two-times greater in frail people compared to robust individuals [9]. A systematic review of elderly patients undergoing colorectal surgery showed that frailty of patients can predict the severity of post-operative complications, with robust patients having significantly better survival rate at 1-year and 5-years [9]. This showcases the importance of classifying the frailty of patients to elect appropriate candidates for surgical management. In particular, classifying patients with rectal prolapse according to frailty as opposed to age alone, may improve patient selection for the different types of operative interventions available (i.e., abdominal vs. perineal approaches).

The modified frailty index (mFI) is a relatively recently developed tool consisting of 11 categories used to classify patients in different levels of frailty [10]. This tool helps classify patients based on frailty and has been shown to predict post-operative outcomes including complications, length of stay and mortality [10, 11]. This frailty index has never been applied to a cohort of patients undergoing surgery for rectal prolapse. As such, the aim of this retrospective study is to use the data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database to assess the relationship between mFI and post-operative outcomes in patients undergoing surgical management for rectal prolapse.

2 Method

2.1 Data source

A retrospective population-based cohort study was performed utilizing the September 1st, 2015, to December 31st, 2019, data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) NIS, managed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The timeline was chosen to capture the years that NIS started utilizing the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes. The NIS is the largest public all-payer inpatient database in the U.S.; it approximates a 20% stratified sample of community hospital discharges, and its included hospitals cover more than 97% of the population, providing a nationally representative sample of the patient population and hospital characteristics. The NIS records information on roughly 7 million hospitalizations annually, including weighted data to help make population estimates. Local ethics board approval was not required for this study.

2.2 Cohort selection

The NIS captures 30 admission diagnoses and 15 admission procedures through the ICD-10-CM codes. Corresponding ICD-10-CM codes were utilized to identify a cohort of adult patients (> 18 years of age) admitted with an admission diagnosis of rectal prolapse. The study group was further narrowed by identifying only those patients who underwent operative intervention for their rectal prolapse by way of either a trans-abdominal approach (i.e., rectopexy, resection rectopexy) or perineal approach (i.e., perineal proctosigmoidectomy). Please see Appendix 1 for detailed ICD-10-CM codes utilized to identify the cohort for this study. Patients with missing data pertaining to age, sex, type of hospital admission (i.e., elective vs. emergent), morbidity, mortality, length of stay, and total in-hospital healthcare cost were excluded.

2.3 Patient and institution characteristics

The patient characteristics included for analysis were age, sex, race category (White, Black, Hispanic, Asian or Pacific Islander, and others), body mass index (BMI), insurance status (Medicare, Medicaid, Private Insurance, Self-pay, and others), and income quartile. Comorbidities were assessed with the Charlson Comorbidity Index software for ICD-10-CM for each individual patient. The institutional characteristics included for analysis were teaching status, rural status, region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West), and bed size (small, medium, large).

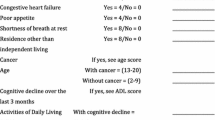

2.4 Modified frailty index

The mFI, as previously described by Velanovich et al. consists of 11 variables: (1) functional health (totally or partially dependent); (2) diabetes mellitus (insulin- or non-insulin dependent); (3) hypertension requiring medication; (4) peripheral vascular disease, history of revascularization or amputation for peripheral vascular disease, rest pain, or gangrene; (5) congestive heart failure within 30-day period prior to surgery; (6) history of myocardial infarction within 6 months prior to surgery; (7) chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or pneumonia; (8) coronary artery disease, history of angina, previous coronary surgery, or prior percutaneous coronary intervention; (9) history of delirium/impaired sensorium; (10) history of transient ischemic attack; and (11) history of cerebrovascular accident (12). Each item was allocated the same weight (1 point) when calculating the index. The mFI was calculated as the number of items present in an individual patient divided by the number of total items. Patients were stratified into two groups based on an mFI cut-off of 0.27, which has been suggested by previous studies to differentiate between individuals of “frail” (i.e., mFI greater than or equal to 0.27) and “robust” (i.e., mFI less than 0.27) status [12]. The original description of the mFI was tailored for data abstraction from the NSQIP database [6]. For the purposes of the present study, the items were adapted to the NIS database through corresponding ICD-10-CM codes (Appendix 1).

2.5 Outcomes

The primary outcomes were overall in-hospital postoperative morbidity and mortality.

Postoperative morbidity was identified with ICD-10-CM diagnosis and procedure codes that explicitly identified individual postoperative outcomes. Specifically, it was a composite of all of the system-specific complications that were encoded using ICD-10 coding (i.e., respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, infectious, and thromboembolic). For postoperative morbidity that was not identifiable by individual ICD-10-CM codes, the AHRQ Patient Safety Indicators were used [13]. The secondary outcomes included system-specific postoperative morbidity, length of stay, total in-hospital healthcare cost, and discharge disposition. System specific complications included; respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, infectious, and thromboembolic using previously utilized methods [14]. Healthcare utilization resources (i.e., length of stay, cost) are recorded in the HCUP NIS. Discharge disposition was categorized into home, short-term hospital, skilled-nursing facility, home healthcare, and others. Due to the nature of the NIS database not having patient identifiers or linkage with other administrative databases, only in-hospital outcomes could be captured and out of hospital outcomes could not be captured.

2.6 Statistical analyses

Patient characteristics are presented as frequencies (%) for categorical variables and means (standard deviations) for continuous variables. Statistical analyses for categorical and continuous variables were performed using the chi square test and two sample t-test, respectively. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models were fit for the primary outcomes and dichotomous secondary outcomes according to an mFI cut-off of 0.27 (i.e., frail vs. robust). Univariable and multivariable linear regression models were fit for the continuous secondary outcomes according to the aforementioned mFI cut-off. All multivariable models were determined a priori by experts in the field on the basis of clinical importance of the covariate. The final model included age, Charlson Comorbidity Index, operative approach, type of operation, insurance status, income quartile, and hospital bed size. For each independent variable in the models, the variation inflation factor (VIF) was calculated to exclude multicollinearity. No sensitivity or subgroup analyses were performed. All statistical tests were two-sided with the threshold for significance set at p < 0.05. Discharge-level weight provided by HCUP was used to calculate national estimates. All statistical analysis was performed using STATA (StataCorp version 15; College Station, TX).

This cohort study was reported based on The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines [15]. A STROBE checklist has been completed and uploaded with this manuscript.

3 Results

3.1 Patient demographics and hospital characteristics

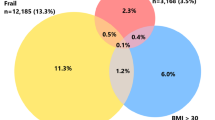

The total patient population included in the analysis was 2,130 with the weighted population estimate of 11,346 patients. The baseline characteristics of included patients were provided in Table 1.

There were 1977 (92.8%) female patients and 239 (11.2%) frail patients, (mFI ≥ 0.27). The mean age was significantly higher in frail patients with mFI ≥ 0.27 compared to robust patients (i.e., mFI < 0.27) (p < 0.001). The median Charlson Comorbidity Index in the frail and robust groups were 8 (IQR 7–9) and 4 (IQR 3–6), respectively (p < 0.001). A greater proportion of frail patients were reliant on Medicare support (84.5% vs 51.3%, p < 0.001) and had lowest residential income (24.3% vs 18.6%, p < 0.001). Fewer frail patients underwent minimally invasive procedures (34.7% vs. 53.7%, p < 0.001). Frail patients were significantly more likely to undergo Altemeier procedures (23.4% vs. 7.4%, p < 0.001) and significantly less likely to undergo rectopexy (67.4% vs. 79.7%, p < 0.001). Frail patients were also operated on more commonly in the emergent setting (19.2% vs. 9.1%, p < 0.001).

3.2 Postoperative morbidity and mortality

In-hospital mortality (OR 10.38, 95% CI 0.65–166.59, p = 0.098), morbidity (OR 2.18, 95% CI 1.31–3.63, p = 0.003) and post-operative ICU admission (OR 4.39, 95% CI 1.10–17.56, p = 0.036) were higher in patients with mFI > 0.27 (Table 2). A system-specific complication analysis showed higher respiratory (OR 4.46, 95% CI 1.37–14.55, p = 0.013), gastrointestinal (OR 2.15, 95% CI 0.75–6.16, p = 0.153) and genitourinary (OR 2.10, 95% CI 1.12–3.95, p = 0.021) complications in frail patients (Table 2).

3.3 Discharge disposition

Patients in the frail group were less likely to be discharged to home following their index operation (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.30–0.74, p = 0.001) and required more home healthcare support (OR 1.70, 95% CI 0.94–3.08, p = 0.077) or were transferred to a nursing care facility (OR 1.60, 95% CI 0.88–2.89, p = 0.120) upon discharge.

3.4 Healthcare resource utilization

Patients in the frail group had significantly longer length of stay (MD 1.32, 95% CI 0.23–2.41, p = 0.018) and prolonged hospital stay (MD 1.60, 95% CI 1.05–2.44, p = 0.028) (Table 3). The adjusted mean difference in overall cost of treatment was $15,561.56 more in the frail group than the robust group (95% CI − 6023.12–37,146.25, p = 0.157).

3.5 Multivariable regression

The multivariable regression analysis showed that increasing mFI was associated with increased odds of experiencing postoperative morbidity (OR 2.18, 95% CI 1.31–3.63, p = 0.003), postoperative mortality (OR 10.38, 95% CI 0.65–166.59, p = 0.098), and reduced odds of being discharged home (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.30–0.74, p = 0.001). Age was not significantly associated with postoperative morbidity (OR 1.01, 95% CI 0.99–1.03, p = 0.348), but was associated with an increased odds of postoperative mortality (OR 1.18, 95% CI 1.05–1.31) and decreased odds of being discharged home (OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.95–0.99, p = 0.001). Minimally invasive surgery was associated with a decreased odds of postoperative morbidity (OR 0.49, 95% CI 0.35–0.69, p < 0.001) and an increased odds of being discharged home (OR 1.71, 95% CI 1.27–2.30, p < 0.001). The remainder of the associations from the multivariable analysis are reported in Table 4.

4 Discussion and conclusions

Rectal prolapse has a negative impact on quality of life of people and its incidence is highest in elderly population [1, 2]. This study aimed to assess the impact of frailty on clinical outcomes and healthcare costs in a cohort of patients undergoing surgical management for rectal prolapse from a 2015–2019 cohort of the NIS. The postoperative morbidity and mortality were significantly higher in frail patients according to the mFI-11. These patients were also less likely to be discharged to home, and generally needed to be discharged to a more healthcare-intensive setting, such as a nursing care home. The length of stay was significantly longer in frail patients. Even though no significant difference was noted, the cost of healthcare utilization was increased in frail patients.

A 2021 systematic review including 17 studies evaluating over 100,000 patients has shown similar results of increase in post-operative morbidity and mortality in frail patients undergoing surgical management for colorectal cancer [16]. In particular, there was a significantly longer length of stay, greater readmission rates, and reoperation rates in patients with a higher frailty score [16]. Similar frailty data have never been published for patients undergoing surgery for rectal prolapse. A 10-year period study published in 2007 by Hammond et al. including 75 patients showed no mortality and a low morbidity of 13% after surgical management for rectal prolapse, not accounting for frailty of patients [17]. Based on age, patients are offered different types of rectal prolapse surgery such that elderly patients often undergo the perineal approach, whereas younger patients often undergo abdominal approaches [3]. However, the studies comparing the effectiveness of these two operations do not take frailty into account [18, 19]. Even though the perineal approach has shown to have lower morbidity, it has also been found to be more prone to recurrence than the abdominal approach [3]. Chronological age and frailty can work synergistically but are not the same processes and cannot be interchanged when making clinical decisions [20]. Frailty is a syndrome which involves physical decline, mental and social changes, increased vulnerability to stressors and high inflammatory state [20]. Even on a molecular biology level, there have been differences noted in inflammatory response in ageing and frailty, depicting that there may be young individuals who are frail, and elderly patients who are robust [21]. Prospective studies have shown frailty to be a better predictor of outcomes compared to age in trauma patients [22]. Perhaps by considering frailty preoperatively, with the use of screening tools such as the mFI-11, people can be offered more targeted approach, including elderly, such that robust individuals are offered abdominal approaches while perineal approaches are reserved for frail patients. This would potentially guard against older, more fit individuals undergoing an operation with a higher recurrence rate simply on the basis of their age.

A 2014 retrospective cohort study by Raizada et al. showed that surgical management was more expensive than non-surgical management of rectal prolapse ($10,432 vs. $3,157) per patient [23]. In a similar 2019 European study by Royo Pérez et al., showed that cost of surgical management is greater than non-surgical management by €4536 [24]. However, none of these studies, stratified patients by age or frailty. Our study does show that frail patients had significantly longer length of stay and health care cost with a mean difference of $15,561.56 compared to patients with a lower mFI. Thus, suggesting that increased frailty may be a contributing factor to increased costs of surgical management, which is already known to be higher than expectant management, as identified by previous studies. Investing in programs designed to mitigate the negative consequences of frailty in the setting of rectal prolapse repair could offer significant cost savings to the healthcare system. Often times, preoperative optimization interventions for elderly, frail patients encompass a significant amount of physical activity, which is low cost and often does not require significant healthcare resource utilization [25]. Multiple clinical trials assessing the impact of prehabilitation in frail patients undergoing colorectal surgery have shown promising outcomes [26, 27, 28]. The PREHAB trial assessing multimodal prehabilitation comprised of high-intensity exercise, nutritional intervention, psychological support and smoking cessation on patients undergoing colorectal surgery showed a significantly lower rate of severe post-operative complications in patients receiving prehabilitation [26]. Another randomized clinical trial with 112 patients showed no difference in patient’s time for 6-min walk test after prehabilitation in colorectal surgery patients [27]. The study did however show walking and breathing has a significantly positive impact on walking capacity compared to biking or strength training suggesting different forms of physical activity may have different impacts, which can be used while devising prehabilitation programs for better outcomes [27]. In a two-centre randomized trial involving patients with poor baseline functional capacity, defined by authors as baseline ventilatory anaerobic threshold < 11 mL/kg/min, undergoing elective colon resection for (pre)malignancy showed significantly less post-operative complications in exercise prehabilitation group [28]. Thus, further development and study of preoperative optimization (i.e., ‘prehabilitation’) programs for frail patients undergoing colorectal surgery, and in particular rectal prolapse surgery, is required. Investment in pre-habilitation and pre-treatment programs may be applied to patients with frailty to reduce overall complications and length of stay, contributing to a reduced cost of surgical management.

The data from our study should be interpreted bearing certain limitations in mind. Only patients undergoing surgical treatment of rectal prolapse were included in the study. As such, they were already considered as being in a higher physical state to tolerate the procedure, further stressing the impact that frailty could have on patients. Despite employing multiple regression analysis to eliminate potential confounding variables, this study is a retrospective study utilizing registry data which could be subject to selection bias. Although the study corrects for sex, age, BMI, and race there is still considerable residual confounding in the form of patient’s comorbidities, surgeon technique for different operations as well as post-operative care given the retrospective nature of the study. Additionally, the study only includes in-patient data and does not provide long-term outpatient follow-up information. While this may not directly impact outcomes between patients who are frail or not, it does underestimate the value of overall resource utilization as well as morbidity post-surgical management for rectal prolapse. Lastly, this is retrospective review of a prospectively managed data registry rather than an intervention-based prospective trial so information about impact of frailty on post-procedure outcomes stratified by different surgeries cannot be delineated. Despite the limitations, this is a nationally representative sample of over 11,000 patients providing a case for considering frailty of patients and its impact on clinical and financial aspects of surgical treatment for rectal prolapse.

After applying the mFI-11 to a cohort of patients undergoing operative intervention for rectal prolapse, it became apparent that frail patients do worse following surgery for this disease. Specifically, frail patients have increased morbidity, longer length of stay, and are more often discharged to nursing care facilities rather than their home. Further studies are needed in the form of granular, patient-level data to understand the impact of frailty, and the different components that comprise this entity, on patient outcomes. Consideration of preoperative optimization programs for frail patients undergoing surgery for rectal prolapse is an important next step to mitigate these poor outcomes.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) National Inpatient Sample from September 1st, 2015, to December 31st, 2019 at https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/tech_assist/centdist.jsp

References

Cannon JA. Evaluation, diagnosis, and medical management of rectal prolapse. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2017;30(1):16–21. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0036-1593431.

Stein EA, Stein DE. Rectal procidentia: diagnosis and management. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2006;16(1):189–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giec.2006.01.014.

El-Dhuwaib Y, Pandyan A, Knowles CH. Epidemiological trends in surgery for rectal prolapse in England 2001–2012: an adult hospital population-based study. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22(10):1359–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.15094.

van der Schans EM, Paulides TJC, Wijffels NA, Consten ECJ. Management of patients with rectal prolapse: the 2017 Dutch guidelines. Tech Coloproctol. 2017;22(8):589–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-018-1830-1.

Senapati A, Gray RG, Middleton LJ, Harding J, Hills RK, Armitage NC, Buckley L, Northover JM. PROSPER Collaborative Group PROSPER: a randomised comparison of surgical treatments for rectal prolapse. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15(7):858–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.12177.

Madiba TE, Baig MK, Wexner SD. Surgical management of rectal prolapse. Arch Surg. 2005;140(1):63–73. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.140.1.63.

Gallo G, Martellucci J, Pellino G, Ghiselli R, Infantino A, Pucciani F, Trompetto M. Consensus statement of the italian society of colorectal surgery (SICCR): management and treatment of complete rectal prolapse. Tech Coloproctol. 2018;22(12):919–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-018-1908-9.

Cawthon PM, Marshall LM, Michael Y, Dam TT, Ensrud KE, Barrett-Connor E, Orwoll ES. Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Research Group. Frailty in older men: prevalence, progression, and relationship with mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(8):1216–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01259.x.

Fagard K, Leonard S, Deschodt M, Devriendt E, Wolthuis A, Prenen H, Flamaing J, Milisen K, Wildiers H, Kenis C. The impact of frailty on postoperative outcomes in individuals aged 65 and over undergoing elective surgery for colorectal cancer: a systematic review. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7(6):479–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2016.06.001.

Velanovich V, Antoine H, Swartz A, Peters D, Rubinfeld I. Accumulating deficits model of frailty and postoperative mortality and morbidity: its application to a national database. J Surg Res. 2013;183(1):104–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2013.01.021.

Xu ZY, Hao XY, Wu D, Song QY, Wang XX. Prognostic value of 11-factor modified frailty index in postoperative adverse outcomes of elderly gastric cancer patients in China. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2023;15(6):1093–103. https://doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v15.i6.1093.

Wahl TS, Graham LA, Hawn MT, Richman J, Hollis RH, Jones CE, Copeland LA, Burns EA, Itani KM, Morris MS. Association of the modified frailty index with 30-day surgical readmission. JAMA surg. 2017;152(8):749–57. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2017.1025.

Quan H, Drösler S, Sundararajan V, Wen E, Burnand B, Couris CM, Halfon P, Januel JM, Kelley E, Klazinga N, Luthi JC, Moskal L, Pradat E, Romano PS, Shepheard J, So L, Sundaresan L, Tournay-Lewis L, Trombert-Paviot B, Webster G, Ghali WA. Adaptation of AHRQ Patient Safety Indicators for Use in ICD-10 Administrative Data by an International Consortium. In K. Henriksen (Eds.) et. al., Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches (Vol. 1: Assessment). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2008.

Storesund A, Haugen AS, Hjortås M, Nortvedt MW, Flaatten H, Eide GE, Boermeester MA, Sevdalis N, Søfteland E. Accuracy of surgical complication rate estimation using ICD-10 codes. Br J Surg. 2019;106(3):236–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10985.

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. STROBE Initiative. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008.

Maturana MM, English WJ, Nandakumar M, Chen JL, Dvorkin L. The impact of frailty on clinical outcomes in colorectal cancer surgery: a systematic literature review. ANZ J Surg. 2021;91(11):2322–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.16941.

Hammond K, Beck DE, Margolin DA, Whitlow CB, Timmcke AE, Hicks TC. Rectal prolapse: a 10-year experience. Ochsner J. 2007;7(1):24–32.

Smedberg J, Graf W, Pekkari K, Hjern F. Comparison of four surgical approaches for rectal prolapse: multicentre randomized clinical trial. BJS open. 2022;6(1):140. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsopen/zrab140.

Lee JL, Yang SS, Park IJ, Yu CS, Kim JC. Comparison of abdominal and perineal procedures for complete rectal prolapse: an analysis of 104 patients. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2014;86(5):249–55. https://doi.org/10.4174/astr.2014.86.5.249.

Gordon EH, Hubbard RE. Frailty: understanding the difference between age and ageing. Age Ageing. 2022;51(8): afac185.

Fedarko NS. The biology of aging and frailty. Clin Geriatr Med. 2011;27(1):27–37.

Joseph B, Pandit V, Zangbar B, Kulvatunyou N, Hashmi A, Green DJ, O'Keeffe T, Tang A, Vercruysse G, Fain MJ, Friese RS, Rhee P. Superiority of frailty over age in predicting outcomes among geriatric trauma patients: a prospective analysis. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(8):766–72.

Raizada A, Abbas MA, Karimuddin AA, Brown CJ, Raval MJ, Phang PT. Cost-effectiveness analysis of surgical versus non-surgical management of rectal prolapse. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29(3):377–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-013-1785-y.

Royo Pérez C, Cárdenas-Camarena L, Durán-Pérez EG, Torres-Villalobos G. Cost-utility analysis of surgical versus non-surgical management of rectal prolapse. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2019;111(7):524–9. https://doi.org/10.17235/reed.2019.6323/2018.

Carli F, Ferreira V. Prehabilitation: a new area of integration between geriatricians, anesthesiologists, and exercise therapists. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2018;30(3):241–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-017-0875-8.

Molenaar CJL, Minnella EM, Coca-Martinez M, Ten Cate DWG, Regis M, Awasthi R, Martínez-Palli G, López-Baamonde M, Sebio-Garcia R, Feo CV, van Rooijen SJ, Schreinemakers JMJ, Bojesen RD, Gögenur I, van den Heuvel ER, Carli F, Slooter GD; PREHAB Study Group Effect of Multimodal Prehabilitation on Reducing Postoperative Complications and Enhancing Functional Capacity Following Colorectal Cancer Surgery: The PREHAB Randomized Clinical Trial [published correction appears in JAMA Surg. 2023;158(6):572–81.

Carli F, Charlebois P, Stein B, Feldman L, Zavorsky G, Kim DJ, Scott S, Mayo NE. Randomized clinical trial of prehabilitation in colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 2010;97(8):1187–97.

Berkel AEM, Bongers BC, Kotte H, Weltevreden P, de Jongh FHC, Eijsvogel MMM, Wymenga M, Bigirwamungu-Bargeman M, van der Palen J, van Det MJ, van Meeteren NLU, Klaase JM. Effects of Community based Exercise Prehabilitation for Patients Scheduled for Colorectal Surgery With High Risk for Postoperative Complications: Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial. Ann Surg. 2022;275(2):e299–e306.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design of the study–Tyler McKechnie, Janhavi Patel, Ghazal Jessani, Yung Lee, Nalin Amin, Aristithes Doumouras, Dennis Hong, Cagla Eskicioglu. Acquisition of data–Tyler McKechnie, Yung Lee. Analysis and interpretation of data–Tyler McKechnie, Janhavi Patel, Ghazal Jessani, Yung Lee, Nalin Amin, Aristithes Doumouras, Dennis Hong, Cagla Eskicioglu. Drafting and revision of the manuscript–Tyler McKechnie, Janhavi Patel, Ghazal Jessani, Yung Lee, Nalin Amin, Aristithes Doumouras, Dennis Hong, Cagla Eskicioglu. Approval of the final version of the manuscript–Tyler McKechnie, Janhavi Patel, Ghazal Jessani, Yung Lee, Nalin Amin, Aristithes Doumouras, Dennis Hong, Cagla Eskicioglu. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work–Tyler McKechnie, Janhavi Patel, Ghazal Jessani, Yung Lee, Nalin Amin, Aristithes Doumouras, Dennis Hong, Cagla Eskicioglu.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Disclosure

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

McKechnie, T., Patel, J., Jessani, G. et al. The impact of frailty on rectal prolapse repair: a retrospective analysis of the national inpatient sample for clinical outcomes and health resource utilization. Discov Med 1, 1 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44337-024-00001-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44337-024-00001-1