Abstract

Delayed massive hemorrhage after biliary surgery is a severe complication and carries a high mortality rate. Upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract bleeding is usually managed endoscopically. However, the presence of altered anatomy following hepato-biliary surgery does preclude endoscopic exploration of the anastomoted loop. In our case of hemorrhage from biliodigestive anastomosis, CT angiography provides accurate information about the presence of active bleeding and its source. We present a case of bleeding from a biliary–digestive loop. The patient exhibited several bleeding risk factors, notably cirrhosis and dual antiplatelet therapy. Furthermore, the site of bleeding, the biliarydigestive loop, had experienced a fistula with a hepatic abscess 2 years earlier, following percutaneous thermoablation. Endovascular embolization with microparticles 300–500 µm and one microcoil 2mx4cm proved to be a safe and effective treatment in this high-risk patient with persistent bleeding. Developments in interventional radiology equipment and techniques, such as low-profile catheter systems and advanced embolic agents, validate embolization as a suitable therapeutic option.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A 79-year-old male with cholecystectomy performed in the 1960s complicated by a biliary-enteric fistula, followed by surgical reoperation and the creation of a bilioenteric anastomosis.

In 2021, we performed percutaneous microwave ablation on a 25 mm HCC (Hepatocellular Carcinoma), located in the V segment of an HCV-related cirrhotic liver. A few days later, we observed the formation of an abscess and the development of a biliary fistula between the abscess and the biliodigestive loop, which was successfully resolved with antibiotic therapy.

In November 2023, in Vascular Surgery Unit, angioplasty and stent placement were performed to treat a stenosis of the right common-internal carotid artery bypass. Following the procedure, a dual antiplatelet therapy regimen was initiated (Cardioaspirin 100 mg/day + Clopidogrel 75 mg/day).

Starting from the beginning of December 2023, the patient was hospitalized for anemia, but endoscopic procedures (1 gastroscopy and 1 colonoscopy) did not reveal any source of bleeding. The patient was treated with intravenous fluid replacement following multiple units of red cell suspension transfusion.

A few days after discharge, the patient was readmitted to the emergency service with recurrent episodes of melena and hematochezia, resulting in anemization HB 6 g/dl (normal: 13.5–18 g/dl). Upon admission, the patient presented with tachycardia and vital signs were recorded as follows: 115 bpm, blood pressure 100/70 mmHg, respiratory rate 14/min, O2 saturation 92% at room air. The INR was 1 and the platelet count was 148 × 109/L. Intravenous fluid replacement following two units of red cell suspension transfusion was initiated in the emergency department. Subsequently, the subject was transferred to the gastroenterology service for further evaluation and follow-up. An upper GI endoscopy was planned but no active bleeding was observed.

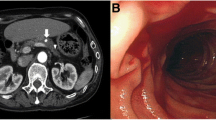

Since endoscopy was unable to explore the bilio-digestive loop, a contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen was conducted. Following the administration of the contrast medium, arterial blush (Fig. 1B) suggestive of active hemorrhage was detected in bowel loops near the biliary-enteric anastomosis, with an increase in blood extravasation in the portal (Fig. 1C) and late venous phases (Fig. 1D).

Considering the high surgical risk, the multidisciplinary team opted to proceed with endovascular embolization for the bleeding. Due to persistent low blood pressure, the patient was managed by the intensive care team.

Angiographic procedures were performed via standard percutaneous transfemoral catheterization using a 5 French (Fr) sheath under local anesthesia. A 5 Fr Cobra (Cordis) catheter was introduced over a 0.035-inch hydrophilic guidewire (Radifocus, Terumo). At the site of the anastomotic loop, two sources of bleeding were identified, originating respectively from distal arterial branches of the right hepatic artery supplying the V hepatic segment (Fig. 2A) and from jejunal branches of the superior mesenteric artery (Fig. 2C).

Angiogram shows the bleeding coming from distal arterial branches of the right hepatic artery supplying the V hepatic segment (A), and from jejunal branches of the superior mesenteric artery (C) (red circle). After embolization with particles and one microcoil no more extravasation of contrast medium was seen (B–D)

Superselective catheterizations were achieved using a microcatheter (Progreat 2.7, Terumo) and the bleeding arteries were embolized with embolic microparticles 300–500 µm (Embosphere, Merit) and one microcoil 2mx4cm (AzurCx 0.018, Terumo), the latter released in a jejunal branch of the superior mesenteric artery (Fig. 2B–D).

The patient returned to hemodynamic stability after the procedure. The dual antiplatelet therapy was discontinued. A contrast-enhanced follow-up CT scan performed 3 days after embolization revealed no signs of active bleeding (Fig. 3). Following an initial episode of metabolic acidosis, lactate levels normalized, and the patient was transferred from the intensive care unit to the general medicine ward. Subsequently, antiplatelet therapy was resumed with only Cardioaspirin.

Discussion

Delayed massive hemorrhage after biliary surgery is a severe complication and carries a high mortality rate [1]. In our case, the hemorrhage originates from ulceration at the biliodigestive anastomosis.

The risk of gastrointestinal bleeding in cirrhotic patients receiving dual anti-platelet therapy is nearly 5 × higher compared to their control counterparts. The use of aspirin alone does not significantly increase the risk of GI bleeding [2].

The presence of a biliodigestive anastomosis and previous bilio-enteric complications likely triggered neoangiogenesis at the level of the anastomosed loop, which also appeared to be supplied by branches of the right hepatic artery for the V segment. The previous fistula between the liver abscess and the bilioenteric loop most likely resulted in structural alterations, rendering its walls more fragile and susceptible to bleeding.

Endoscopy is commonly employed as the initial approach for investigating and managing acute GI tract bleeding [3, 4]. Recent literature highlights the higher technical success rates of endovascular embolization, attributed to advancements in microcatheter, microguide, and embolic agent technologies, coupled with improvements in angiography techniques. The most serious, albeit infrequent, complication of transarterial embolization (TAE) is bowel ischemia or infarction. The risk of significant ischemia increases with embolic agents that advance distal into the vascular bed, such as liquid agents and very small particles. Utilizing coils and medium-to-large particles to large particles (> 300 µm) offers the main advantage of preserving the distal microvasculature.

Embolization has the advantage of avoiding laparotomy in the unfit and elderly population [5]. Surgery has the disadvantage of high rates of postoperative morbidity and mortality.

The typical candidate for endovascular embolization presents with bleeding and/or hypotension, characterized by a systolic pressure of less than 100 mmHg and heart rate of 100/min, who does not respond to conservative medical therapy involving volume replacement and transfusion [6]. The patient must not present a condition of severe hemodynamic instability to be taken to the angiographic room.

In cases where a dual supply of the bleeding area is suspected, both arterial sources need to be embolized to ensure that all the inflow ceases. The role of TAE is to selectively reduce blood supply at the source of bleeding while maintaining enough collateral blood flow to safeguard intestinal viability.

Conclusion

Massive bleeding from the upper tract remains a challenge. It is essential to have a multidisciplinary team composed of skilled endoscopists, intensive care specialists, experienced upper gastrointestinal surgeons, and interventional radiologists, each contributing their expertise to effectively manage the condition.

In this case of hemorrhage from biliodigestive anastomosis, endovascular embolization proved to be a safe and effective treatment strategy in a high-risk patient with persistent upper GI bleeding.

Data availability

The data, if requested, will be available.

References

De Castro SM, Kuhlmann KF, Busch OR et al (2005) Delayed massive hemorrhage after pancreatic and biliary surgery. Ann Surg 241(1):85–91. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000150169.22834.13

Spence L, Russo M, Benbow J, Padilla L, Anderson W, Schrum L (2018) The risk of gastrointestinal bleeding is higher in patients with underlying cirrhosis on dual antiplatelet therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. https://doi.org/10.14309/00000434-201810001-00950

Artigas JM, Martí M, Soto JA, Esteban H, Pinilla I, Guillén E (2013) Multidetector CT angiography for acute gastrointestinal bleeding: Technique and findings. Radiographics 33(5):1453–1470. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.335125072

Hongsakul K, Pakdeejit S, Tanutit P (2014) Outcome and predictive factors of successful transarterial embolization for the treatment of acute gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Acta Radiol 55(2):186–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/0284185113494985

Beggs A et al (2014) A systematic review of transarterial embolization versus emergency surgery in treatment of major nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. https://doi.org/10.2147/ceg.s56725

Loffroy R et al (2015) Transcatheter arterial embolization for acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: Indications, techniques and outcomes. Diagn Interv Imaging 96(7–8):731–744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diii.2015.05.002

Funding

This study was not supported by any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Matteo Vincenzi and Giovanni Balestriero performed the embolization and they are involved in plan and draft the manuscript. Benedetta Rigoni has made important contributions to CT image acquisition and interpretation. Matteo Mazzoli has made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the manuscript. Carla Manupelli oversaw the clinical management of the patient and provided the clinical data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

For this type of paper ethics approval/declarations is not required.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from Patient.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vincenzi, M., Rigoni, B., Manuppelli, C. et al. Endovascular embolization of a biliary–digestive loop bleeding. J Med Imaging Intervent Radiol 11, 18 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44326-024-00008-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44326-024-00008-z