Abstract

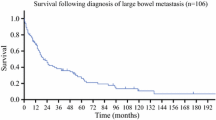

Melanoma represents approximately 5% of all the skin cancers and is well known for its ability to metastasize to a wide range of atypical locations. Organs most commonly affected by metastatic melanoma include liver, lung and brain, but spread to the gastrointestinal tract is not uncommon and small bowel involvement ranges from 51 to 71% of the cases. Given the nonspecific nature of the clinical presentation and the broad differential diagnosis, the prompt choice of imaging modality and its correct interpretation is important in order to perform a timely diagnosis. Early diagnosis and treatment of these lesions improve survival and quality of life, even in palliative cases. In this narrative review, we analyze the different imaging modalities used in the diagnosis of gastrointestinal metastases from melanoma. Typical radiological signs supporting the radiologists in interpreting images are also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Malignant melanoma is the cause of 1–3% of the global neoplastic diseases [1], and it is the most aggressive form of skin cancer, with a tendency to metastasize to any organ. It is characterized by its high metastatic potential and poor prognosis [2].

The global incidence of melanoma continues to rise, and the mortality associated with unresectable or metastatic melanoma remains high. Globally, 132,000 new cases of melanoma are diagnosed and an estimated 48,000 people die from advanced melanoma each year [3]. Malignant melanoma is the most common cause of mortality due to skin cancer worldwide and its incidence is increasing [4]. Melanoma is the fifth most common cancer in man and the sixth in women [5].

Melanomas are derived from melanocytes, which originate in the neural crest and are widely distributed through the skin and other tissues. Many melanomas develop on sunlight-exposed areas. Primary melanoma most commonly arises from the skin; however, it can also develop in other areas, including the eye and mucosae. It is a tumor arising from the malignant proliferation of melanocytes that derived from neural crest cells, which can be present on the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and brain [6]. Melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract (GI) is rarely detected as a primary neoplasm, since more frequently a primary cutaneous melanoma develops metastases to the GI tract [7]. Malignant melanoma is the most common carcinoma to metastasize to the GI and has an affinity to spread to the small bowel (51%-71% of cases), especially to the jejunum and ileum. This can be explained by the strong melanoma cell surface expression of CCR9, a chemokine receptor, for which its CCR9 ligand, CCL25, is highly expressed in the small intestine.

The involvement of the small bowel is followed by metastatic spread to the stomach (27%), large intestine (22%) and esophagus (5%) [8]. The major risk factor for melanoma is skin color, the presence of a large number of dysplasic melanocytic nevi, a family history of melanoma and the sunlight exposure [9]. Patients with metastatic melanoma are staged according to TNM (AJCC 8th edition) in local disease (stage I–II), node-positive disease (stage III) and advanced/metastatic disease (stage IV). Patients with metastatic involvement of the GI tract have stage IV disease [10].

Due to the increasing incidence of metastatic malignant melanoma, there is a substantial need for effective therapies that can further improve patient survival. Improved imaging of metastatic disease is crucial for selection of effective therapy options. However, there is very little literature on targeted imaging of metastatic patterns of melanoma. Few studies, for example, were dedicated to imaging and metastatic spread of melanoma subtypes [11].

In this narrative review, we analyze the different imaging modalities used in the diagnosis of gastrointestinal metastases from melanoma. Typical radiological signs supporting the radiologists in interpreting images are also discussed.

Imaging of gastrointestinal metastatic melanoma

Clinical examination with endoscopic and radiological imaging is essential for diagnosis of gastrointestinal metastatic melanoma.

Diagnosis of metastatic melanoma to the gastrointestinal tract is generally performed by contrast studies, ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET).

An optimal approach to improve sensitivity for the detection of gastrointestinal melanoma metastases is the use of 18F FDG-PET/CT for whole-body staging of malignant melanoma [11]. The increased metabolic activity of melanoma metastases, marked by a high 18F FDG uptake, helps to overcome the sometimes limited sensitivity of other imaging techniques relying on morphological assessment alone such as contrast-enhanced CT, which is the present standard for staging of malignant melanoma. This is of special interest in small bowel metastases as these are not accessible to endoscopy and not suitable for video capsule passage due to impaired intestinal passage [11].

Early stages of small intestine metastases can be clinically silent, and the diagnosis is difficult [2]. Conventional X-ray imaging does not assure diagnostic advantages for metastases, but is useful to diagnose an intestinal obstruction [12]. Plain abdominal film can reveal the presence of small bowel distension with multiple air-fluid levels [13]. Barium studies, such as enteroclysis and small bowel follow-through examinations can be used for early detection of suspected small bowel masses [14]. The technique accurately detects luminal abnormalities, including low-grade bowel obstruction, but does not show important extraintestinal findings. Therefore, enteroclysis is not sufficient to exclude diagnosis of small bowel neoplasm and further techniques might be needed [15]. Abdominal ultrasonography is frequently chosen as a first screening method because it is noninvasive and does not require special preparation. Sonography is, furthermore, readily accessible and inexpensive. In fact, abdominal sonography of the gastrointestinal tract has become widely recognized as a directed tool to examine bowel disorders in patients with abdominal pain [16]. With high-frequency ultrasound, the individual bowel wall layers of a small bowel intussusception are easily appreciated as either concentric rings, when scanning transversely across the bowel or as hypoechoic and hyperechoic stripes, when viewing the bowel longitudinally. It is also possible to search for an associated lead point, such as a mural tumor [17]. On longitudinal view, the characteristic hayfork or sandwich sign is formed by three parallel hypoechoic areas separated by hyperechoic zones. These zones represent the dilated intussuscipiens containing the intussusceptum and is considered pathognomonic for intussusception. Alternatively, the appearance of a pseudokidney sign is formed if the intussusception is curved and when the mesentery is seen on only one side of the intussusceptum. On axial view, there is a hypoechoic ring from the edematous wall of the intussuscipiens around an echo-dense center formed by the interface of the mucosal and serosal layers of the intussusceptum. This characteristic sign is called by several names including “bulls eye sign”, “target sign”, “donut sign” or “concentric ring sign” [18]. However, obesity and the presence of massive air in the distended bowel loops limit the image quality and the subsequent diagnostic accuracy [19].

In the clinical practice, the most commonly observed pattern is represented by multiple mural polypoid lesions in the jejunum or ileum that appear as multiple intraluminal filling defects on barium studies and enhancing intraluminal nodules on CT [20]. Intraluminal polypoid nodules can mimic carcinoid tumors, primary small bowel carcinoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, lymphoma, or other intestinal metastases.

Nowadays, CT examination is the most preferred modality of investigation [21]: CT scans have a sensitivity of 60–70% for detecting metastases [22]. Due to the CT accuracy, the lesion could be localized in the stomach or in the small bowel. CT images additionally can demonstrate a “crescent-in-doughnut sign” and a “sandwich sign”, typical CT signs of invagination [23] (Fig. 1). CT has accuracy close to 80%, but it needs an experienced radiologist to recognize an intraluminal lesion acting as a lead point [24]. These specific findings can be clearly visible or they can remain undetected due to edema; in these cases, the classic three-layer appearance and anatomic detail are often lost and consequently an irregularity mass can show the intussusception [25].

A 89-year-old man presented in emergency department with abdominal pain, vomiting and bowel closed to feces and gas. His medical history consisted in known lung and liver metastases from primary melanoma. Its lab exams showed only mild neutrophilia. Abdominal X-ray and sonographic examination were performed before CT in the emergency setting. The patient underwent ileal resection surgery with ileostomy. The CT images (A – B: axial view; C: MPR coronal view) show the ileoileal intussusception with crescent-in-doughnut sign; to observe the intussuscepted intestine and the mesentery dragged into the intussusception

On imaging, a common manifestation of small bowel metastases from melanoma is mural thickening that may result in an aneurysmal pattern [26]. Such appearance is defined as a cavitary dilatation of the intestinal lumen (> 4 cm) with a nodular, irregular luminal contour and peripheral bowel wall thickening and was first described as an imaging finding characteristic of lymphoma [27].

CT-enteroclysis increases the sensitivity and specificity of detecting bowel wall and intraluminal pathology, resulting in better detection of the exact site, degree, and cause of obstruction than obtained with CT and, possibly, with enteroclysis. It should be considered as the first-line imaging modality in the clinical setting of recurrent, low-grade of obstructive symptoms [28].

On magnetic resonance Imaging (MRI), melanoma metastases are classically described as having high-signal intensity on T1-weighted (T1W) imaging and mixed-signal intensity on T2-weighted (T2W) imaging and marked enhancement on post-contrast T1-weighted images [29].

Whole-body PET scan with fluorodeoxyglucose has a higher sensitivity and specificity than conventional CT for detecting gastrointestinal metastases in melanoma patients. In fact, some researchers believe that PET should be the primary staging test for disease recurrence [30].

For a precise diagnosis of GI involvement by a metastatic melanoma, there are excellent endoscopic options, including video capsule endoscopy and enteroscopy [31]. Small bowel capsule endoscopy (SBCE) is a useful tool for detecting small bowel tumors, primary or metastatic [32]. Video capsule endoscopy has opened a new opportunity in small bowel evaluation, allowing a complete direct visualization of the small intestine [33].

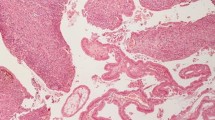

Immunohistochemical stains are needed to confirm diagnosis of malignant melanoma; the S100 sensitivity varies between 33 and 100%, and HMB-45 antibodies has sensitivity between 80 and 97%, but the specificity is high (100%) [34] (Fig. 2).

A Histologically, a polypoid neoplastic proliferation is found, which ulcerates the mucosa and infiltrates the entire thickness of the intestine (H&E staining; 2.5 × magnification; scale bar 1 mm). B The neoplasm shows a diffuse growth pattern, infiltrating even the intestinal glands, composed of epithelioid and fusiform cells, with evident cytological atypia (H&E staining, 10 × magnification, scale bar 200 µm). (C – E) Immunohistochemical analysis reveals positivity for MART-1 (C), S100 (D), and negativity for CK20 (E), which is positive in intestinal cells (immunohistochemistry staining, 10 × magnification, scale bar 200 µm)

The main characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Discussion

Primary intra-abdominal melanoma can be difficult to differentiate from metastatic melanoma since the primary skin lesion can sometimes regress, remain undiscovered, or become unknowingly removed. Up to 4–10% of the melanoma cases have an unknown primary site [20].

Melanomas are capable of metastasizing to both regional and distant sites and are notably known to metastasize to the skin, lungs, brain, liver, bone [35]. The frequency of GI metastases is difficult to estimate, but autopsy series suggest that this represents a common site of metastatic spread, often in greater than 50% of the patients [36]. The small intestine is the most frequent site of metastatic melanoma in the GI tract [37]; however, small bowel involvement is found at postmortem in 50–60% of the melanoma patients and diagnosis is only made during life in 10% of the cases [38].

The average time from initial diagnosis of melanoma to development of small bowel metastases ranges from 3 to 6 years [20].

Small bowel neoplasms can be asymptomatic; even when symptomatic, they often have a bowel and nonspecific clinical manifestation, with symptoms including intermittent abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and weight loss. Small bowel neoplasms can lead to complications including jaundice, gastrointestinal bleeding, obstruction, and perforation [39]. Bowel obstruction is a representative symptom of intestinal metastasize of malignant melanoma and intussusception is most frequent cause in this entity [40]. The tendency of metastatic melanoma to form a gastrointestinal mass that acts as lead point causing intussusception as been reported in few cases. The variable presentation of adult intussusception along with a low index of suspicion for the condition, given its rarity, makes diagnosis challenging [41]. A study by Bender et al. [42] revealed that the polypoid pattern is the most common manifestation of metastatic melanoma to the small bowel. This study determines the frequency of different pattern of melanoma metastases to small bowel on radiological examination and compared it to the findings at surgery and at autopsy. Metastases were categorized as polypoid, cavitary, infiltrating or exoenteric. In a total of 32 patients, the polypoid pattern was seen in 20 patients (63%), 8 patients (25%) demonstrated a cavitary pattern, a circumferential mass with inner marginal necrosis, and 5 (16%) showed an infiltrating pattern. One patient (3%) had an exoenteric lesion with a fistulous tract. Patterns of metastasis to the small bowel are shown in Table 2.

Patients with metastatic melanoma to the small intestine may benefit from surgical intervention especially in cases of complete resection of demonstrable disease or in cases of palliative care [43].

Conclusion

In adults, given the nonspecific nature of the clinical presentation and the broad differential diagnosis, the choice of imaging modality is important in order to perform a timely diagnosis. Knowledge of the different imaging methods can accelerate the diagnosis and, consequently, facilitate elective treatment avoiding non-elective hospitalization.

In conclusion, gastrointestinal metastatic melanoma should always be suspected in any case of patient with a history of malignant melanoma and anemia or even in patients with specific symptoms. Recognition of unusual radiological signs affecting the gastrointestinal tract is important to accelerate the diagnosis, to provide adequate treatment and to improve the quality of life and increase the survival of these patients, even in palliative cases.

Data availability

Not applicable, considering the review article.

References

Sinagra E, Sciumè C (2020) Ileal melanoma, a rare cause of small bowel obstruction: report of a case, and short literature review. Curr Radiopharm 13:56–62. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874471012666191015101410

Fan WJ, Cheng HH, Wei W (2023) Surgical treatments of recurrent small intestine metastatic melanoma manifesting with gastrointestinal hemorrhage and intussusception: a case report. World J Gastrointest Oncol 15:205–214. https://doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v15.i1.205

Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, Dutriaux C, Maio M, Mortier L, Hassel JC, Rutkowski P, McNeil C, Kalinka-Warzocha E, Savage KJ, Hernberg MM, Lebbé C, Charles J, Mihalcioiu C, Chiarion-Sileni V, Mauch C, Cognetti F, Arance A, Schmidt H, Schadendorf D, Gogas H, Lundgren-Eriksson L, Horak C, Sharkey B, Waxman IM, Atkinson V, Ascierto PA (2015) Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med 372:320–330. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1412082

Chaves J, Libânio D (2022) Metastatic malignant melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract: too dark to be seen? GE Port J Gastroenterol 30:1–3. https://doi.org/10.1159/000527210

Dzwierzynski WW (2021) Melanoma risk factors and prevention. Clin Plast Surg 48:543–550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cps.2021.05.001

Galindo L, Traylor C, Check L, Faris M (2023) Primary left thigh melanoma presenting as an obstructive hemorrhagic melanoma of the small bowel. Cureus 15:e42428. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.42428

Gallino G, Maurichi A, Patuzzo R, Mattavelli I, Barbieri C, Leva A, Valeri B, Cossa M, Galeone C, Pelucchi C, Santinami M (2021) Surgical treatment of melanoma metastases to the small bowel: a single cancer referral center real-life experience. Eur J Surg Oncol 47:409–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2020.08.025

Kohoutova D, Worku D, Aziz H, Teare J, Weir J, Larkin J (2021) Malignant melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract: symptoms, diagnosis, and current treatment options. Cells 10:327. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10020327

Marks R (2000) Epidemiology of melanoma. Clin Exp Dermatol 25:459–463. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2230.2000.00693.x

Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, Sondak VK, Long GV, Ross MI, Lazar AJ, Faries MB, Kirkwood JM, McArthur GA, Haydu LE, Eggermont AMM, Flaherty KT, Balch CM, Thompson JF (2017) Melanoma staging: evidence-based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin, 67:472–492

Othman AE, Eigentler TK, Bier G, Pfannenberg C, Bösmüller H, Thiel C, Garbe C, Nikolaou K, Klumpp B (2017) Imaging of gastrointestinal melanoma metastases: correlation with surgery and histopathology of resected specimen. Eur Radiol 27:2538–2545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-016-4625-7

Stagnitti F, Orsini S, Martellucci A, Tudisco A, Avallone M, Aiuti F, Di Girolamo V, Stefanelli F, De Angelis F, Di Grazia C, Napoleoni A, Nicodemi S, Cipriani B, Ceci F, Mosillo R, Corelli S, Casciaro G, Spaziani E (2014) Small bowel intussussception due to metastatic melanoma of unknown primary site. Case report G Chir 35:246–249

Soares F, Brandão P, da Inez Correia R, Valente V (2019) Small bowel obstruction due to intraluminal metastasis from malignant melanoma. J Surg Case, 2019:rjz044

Buckley JA, Fishman EK (1998) CT evaluation of small bowel neoplasms: spectrum of disease. Radiographics 18:379–392. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiographics.18.2.9536485

Lens M, Bataille V, Krivokapic Z (2009) Melanoma of the small intestine. Lancet Oncol 10:516–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70036-1

Ledermann HP, Binkert C, Fröhlich E, Börner N, Zollikofer C, Stuckmann G (2001) Diagnosis of symptomatic intestinal metastases using transabdominal sonography and sonographically guided puncture. AJR Am J Roentgenol 176:155–158. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.176.1.1760155

Wale A, Pilcher J (2016) Current role of ultrasound in small bowel imaging. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 37:301–312. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sult.2016.03.001

Ramsey KW, Halm BM (2014) Diagnosis of intussusception using bedside ultrasound by a pediatric resident in the emergency department. Hawaii J Med Public Health 73:58–60

Marinis A, Yiallourou A, Samanides L, Dafnios N, Anastasopoulos G, Vassiliou I, Theodosopoulos T (2009) Intussusception of the bowel in adults: a review. World J Gastroenterol 15:407–411. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.407

Chang ST, Desser TS, Gayer G, Menias CO (2014) Metastatic melanoma in the chest and abdomen: the great radiologic imitator. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 35:272–289. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sult.2014.02.001

Patel RB, Vasava NC, Gandhi MB (2012) Acute small bowel obstruction due to intussusception of malignant amelonatic melanoma of the small intestine. BMJ Case Rep 2012:bcr2012006352. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2012-006352

Atiq O, Khan AS, Abrams GA (2012) Metastatic amelanotic melanoma of the jejunum diagnosed on capsule endoscopy. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY) 8:691–693

Strobel K, Skalsky J, Hany TF, Dummer R, Steinert HC (2007) Small bowel invagination caused by intestinal melanoma metastasis: unsuspected diagnosis by FDG-PET/CT imaging. Clin Nucl Med 32:213–214. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.rlu.0000255212.17086.e9

Đokić M, Badovinac D, Petrič M, Trotovšek B (2018) An unusual presentation of metastatic malignant melanoma causing jejuno-jejunal intussusception: a case report. J Med Case Rep 12:337. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-018-1887-5

Panzera F, Di Venere B, Rizzi M, Biscaglia A, Praticò CA, Nasti G, Mardighian A, Nunes TF, Inchingolo R (2021) Bowel intussusception in adult: prevalence, diagnostic tools and therapy. World J Methodol 11:81–87. https://doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v11.i3.81

Barat M, Guegan-Bart S, Cottereau AS, Guillo E, Hoeffel C, Barret M, Gaujoux S, Dohan A, Soyer P (2021) CT, MRI and PET/CT features of abdominal manifestations of cutaneous melanoma: a review of current concepts in the era of tumor-specific therapies. Abdom Radiol (NY) 46:2219–2235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-020-02837-4

Mendes Serrao E, Joslin E, McMorran V, Hough C, Palmer C, McDonald S, Cargill E, Shaw AS, O’Carrigan B, Parkinson CA, Corrie PG, Sadler TJ (2022) The forgotten appearance of metastatic melanoma in the small bowel. Cancer Imag 22:27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40644-022-00463-5

Walsh DW, Bender GN, Timmons H (1998) Comparison of computed tomography-enteroclysis and traditional computed tomography in the setting of suspected partial small bowel obstruction. Emerg Radiol 5:29–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02749123

Serrao EM, Costa AM, Ferreira S, McMorran V, Cargill E, Hough C, Shaw AS, O’Carrigan B, Parkinson CA, Corrie PG, Sadler TJ (2022) The different faces of metastatic melanoma in the gastrointestinal tract. Insights Imag 13:161. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13244-022-01294-5

Wu F, Lee MS, Kim DE (2022) Small bowel obstruction caused by hemorrhagic metastatic melanoma: case report and literature review. J Surg Case Rep 2022:rjac395. https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjac395

Ionescu S, Nicolescu AC, Madge OL, Simion L, Marincas M, Ceausu M (2022) Intra-abdominal malignant melanoma: challenging aspects of epidemiology, clinical and paraclinical diagnosis and optimal treatment - a literature review. Diagnostics (Basel) 12:2054. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12092054

Aerts MA, Mana F, Neyns B, De Looze D, Reenaers C, Urbain D (2012) Small bowel metastases from melanoma: does videocapsule provide additional information after FDG positron emission tomography? Acta Gastroenterol Belg 75:219–221

Spada C, Riccioni ME, Familiari P, Marchese M, Bizzotto A, Costamagna G (2008) Video capsule endoscopy in small-bowel tumours: a single centre experience. Scand J Gastroenterol 43:497–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365520701797256

Ettahri H, Elomrani F, Elkabous M, Rimani M, Boutayeb S, Mrabti H, Errihani H (2015) Duodenal and gallbladder metastasis of regressive melanoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Gastrointest Oncol 6:E77–E81. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2015.048

Froes C, Scibelli N, Carter MK (2022) Case report of metastatic melanoma presenting as an unusual cause of gastrointestinal hemorrhage in an elderly gentleman. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 78:103920. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2022.103920

Schuchter LM, Green R, Fraker D (2000) Primary and metastatic diseases in malignant melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Curr Opin Oncol 12:181–185. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001622-200003000-00014

Blecker D, Abraham S, Furth EE, Kochman ML (1999) Melanoma in the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Gastroenterol 94:3427–3433. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01604.x

Prakoso E, Selby WS (2007) Capsule endoscopy in patients with malignant melanoma. Am J Gastroenterol 102:1204–1208. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01115.x

Jasti R, Carucci LR (2020) Small bowel neoplasms: a pictorial review. Radiographics 40:1020–1038. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2020200011

Kumano K, Enomoto T, Kitaguchi D, Owada Y, Ohara Y, Oda T (2020) Intussusception induced by gastrointestinal metastasis of malignant melanoma: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 71:102–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2020.03.026

Kharroubi H, Osman B, Kakati RT, Korman R, Khalife MJ (2022) Metastatic melanoma to the small bowel causing intussusception: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 93:106916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2022.106916

Bender GN, Maglinte DD, McLarney JH, Rex D, Kelvin FM (2001) Malignant melanoma: patterns of metastasis to the small bowel, reliability of imaging studies, and clinical relevance. Am J Gastroenterol 96:2392–2400. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04041.x

Alkhatib AA (2019) Metastatic melanoma to the jejunum. Arab J Gastroenterol 20:105–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajg.2018.12.005

Funding

All the authors have declared that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lo Mastro, A., Grassi, R., Reginelli, A. et al. Gastrointestinal metastatic melanoma: imaging findings and review of literature. J Med Imaging Intervent Radiol 11, 2 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44326-024-00003-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44326-024-00003-4