Abstract

One of the most worrying issues in Spanish education is the high school dropout rate, especially for those students who leave compulsory secondary education with no qualifications. Some of these students re-enter the system via adult education centres (AECs), where they can obtain the minimum qualification required by the labour market (the Secondary Education Graduate Certificate, the equivalent of GCSE in UK education). Entry into and adaptation to the AECs was explored in a non-probabilistic sample of 234 individuals from a total population of 2033 enrolled in 14 Catalan AECs, and the roles of a range of factors in shaping successful trajectories were analysed. The aim was to contribute to the design of strategies boosting students’ well-being and raising the probability of their persisting in their studies. The results showed that when study was full-time or combined with a part-time job of half a day or fewer working hours, when there was high academic satisfaction with the centre, and when there was a feeling of empowerment and efficacy in studying, the bond to the centre and the will to continue studying there were enhanced.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In the current Spanish education system, if there is one issue that particularly concerns the various bodies that design and deliver education policy, it is the high school dropout rate. While the percentage of students aged 18 to 24 who had not completed the second stage of secondary education (Basic and Intermediate Vocational Training or Baccalaureate) stood at 13.3% in 2021, decreasing from 16% in 2020 according to the Spanish Labour Force Survey (EPA) of the National Statistics Institute (INE), Spain is still one of the developed countries with the highest dropout rates.

However, the academic careers of these students are not cut short only at high school. This is the outcome of a process beginning much earlier (Salvà-Mut et al., 2014), a gradual disengagement that stretches across their whole education (Archambault et al., 2022), particularly in the case of people who do not obtain the Compulsory Secondary Education (ESO) Certificate, the minimum qualification needed to continue their education.

In this sense, the research presented here focuses on a more vulnerable group of people who, having left the education system without any qualifications, return to their studies due to a lack of opportunities in both employment and further training. The main objective of the study was to analyse the impact of adult education on their personal and professional pathways. Thus, we focus particularly on adult students taking the Secondary Education Graduate Certificate (GES or adult secondary education) in order to obtain the compulsory secondary education qualification. This is a programme that in Spain can be taken in adult education centres (AECs hereinafter), opening the door to continuing education via the baccalaureate or an intermediate level vocational training course (CFGM).

The AECs have become an important means of bringing young people back into education. The centres offer a broad range of programmes (Sánchez Guerrero et al., 2020), amongst them adult secondary education, which is organised into two levels of one year each. To obtain the qualification, a total of 34 quarterly modules must be taken and, if necessary, validated or accredited. The GES, therefore, can also be taken in a shorter time, depending on students’ previous education (Spanish Decret 161/2009, of October 27, on the organization of compulsory secondary education for adults) (Departament d'Educació 2009).

The increasing popularity of AEC courses has led to a change in traditional student profiles. Thus, there has been an increase in numbers of students aged between 16 and 25 from differing social backgrounds and at varying stages of their lives: very young students expelled from ESO due to failure and early dropout; students who study and work at the same time; unemployed students; and older students seeking to complete ESO despite having obtained the former EGB high-school certificate (DIBA, 2019; ESREA, 2017; Rujas, 2015). This growth has also been boosted by the recent pandemic, which increased the numbers of people returning to school. However, once they start, the challenge for these students is to complete their courses. According to data from the Spanish Education Ministry (MECD, 2022), the percentage of the population obtaining the ESO diploma through the AECs, including the free exams, is 7.0%, compared to 84% who pass it as 15-year-olds.

This situation requires an in-depth investigation of successful adult secondary education pathways. To this end, it is essential to explore students’ process of adaptation and integration into the institution, as this is a key factor in explaining continuity and completion of studies. The literature on this process mostly centres on transitions during secondary school or to university, with less research on adult secondary education (Salvà-Mut et al., 2014; Vorhaus et al., 2011). Sociological studies scrutinise variables such as social class, family educational qualifications, and previous educational outcomes as determinants in secondary education transition processes (Bernardi & Cebolla, 2014; Bernardi & Triventi, 2018; Breen & Jonsson, 2000). Along the same lines, transitions to university have been analysed (Daza et al., 2019; Elias et al., 2023). However, given that adult learners form a highly homogeneous social group, it is important to consider other types of variables bearing on decision-making.

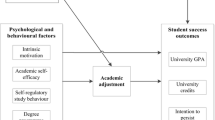

Psychological research stresses cognitive factors and others linked to the learner’s wellbeing. One of these is the feeling of self-efficacy (Bandura, 1999). When a person experiences this perception of their study competences, their level of satisfaction increases, and the process of adaptation is boosted, thus leading to successful outcomes (Lent et al., 2005). Similar conclusions have been reached on the impact of academic self-efficacy and motivation on academic satisfaction and achievement (Huebner & McCullough, 2000). Thus, students’ beliefs and attitudes regarding motivation, another important measure, play a key role in their academic satisfaction and success. Vu et al. (2021) reviewed the evidence on the relationship between motivation and achievement, and concluded that there is a need to explore further the reciprocal relationship between the two variables. Fan and Wolters (2014) add the mediating role of students’ educational expectations to this binomial. On the other hand, Anttila et al. (2022), in a longitudinal study among Finnish secondary school students, found that motivational beliefs and behaviours, high expectations of success and low task avoidance predicted the intention to persist.

Another factor that has been explored is satisfaction (Lent et al., 2009; Lodi et al., 2019). This is a complex construct measured by various indicators and clearly related to persistence (Magnano et al., 2020). Satisfaction often acts as a mediating factor between variables linked to the student’s personal and family characteristics and academic performance (Weber & Harzer, 2022). However, the association between satisfaction and educational success, as well as that between academic self-efficacy and good performance, are also reciprocal in nature. Students with higher satisfaction or more self-efficacy are more likely to persist, but the reverse is also true (Schunk & DiBenedetto, 2014). School satisfaction has also shown strong correlations with factors associated with school atmosphere, such as teacher support and the teacher-student relationships (Coelho & Dell'Aglio, 2019; Zullig et al., 2011).

Students’ relationships with peers and teachers, in the area of academic and personal support, is another important construct when analysing persistence, and is often linked to the study of engagement (Affuso et al., 2023; Fraysier & Reschly, 2022; Reschly, 2020). Receiving support from teachers and maintaining quality student–teacher relationships is often associated with greater persistence and better educational outcomes (Wang & Eccles, 2013). Lack of connection with teachers leads to feelings of alienation, failure and disaffection with the school, causing students to drop out (Bernstein-Yamashiro & Noam, 2013). Other studies use personal, family and context variables to frame their statistical models, since it has been observed that these relationships can be altered by educational transitions and this may increase the likelihood of dropping out (Rumberger & Palardy, 2005). It has also been observed that relationships with teachers and peers may have a mediating effect between engagement and study performance and persistence (Affuso et al., 2023; Konold et al., 2018; López et al., 2007). Much less research examines the impact of peer relationships. In this regard, Orpinas & Raczynsky (2016) concluded that being the victim of rumours or lies, being left out on purpose or being forced to do things in order to be liked increased the likelihood of dropping out.

Although much less attention has been paid to the field of adult education, some of the variables reviewed above reappear, sometimes with greater force, in studies of the education careers of this group. In an analysis of barriers to persistence in UK adult education, Lister (2007) found that one of the most important factors was the student’s attitude to learning, which was mainly explained by accumulated previous experiences giving rise to greater or lesser confidence and motivation to continue. Lister, however, also nuanced his findings according to student profiles. On the other hand, some studies have found that demographic differences among those who drop out and those who persist are not significant (Melrose, 2014). A further barrier identified is work (Bélanger, 2011; Lister, 2007). While this variable does not appear in the studies previously reviewed, since they mostly concern people of school age, it takes on greater relief in the case of older students. Amongst these people, having a paid job makes it more difficult to engage and follow through with their education.

Continuing with socio-cognitive factors, those that have the greatest influence on persistence are high satisfaction (Lister, 2007), mentoring and support from teachers (Lister, 2007; Macedo et al., 2011; Savelsberg et al., 2017), motivation (Gorard & Smith, 2004; MacLeod & Straw, 2010; Vorhaus et al., 2011; Webb, 2006), receiving support in the process of joining the institution (Quigley & Uhland, 2000), and receiving sufficient information and guidance throughout the same process (López et al., 2007).

2 Method

This is a quantitative study whose objective was to explore the success factors of people enrolled in secondary education courses in AECs in Catalonia.Footnote 1 The specific objectives of the study were twofold: (a) to examine the changes produced in the levels of motivation, satisfaction, self-efficacy and social and academic support of adults before and after enrolling in AECs; and (b) to analyse which variables had a greater impact on their intention to persist in their studies.

2.1 Participants

The study population comprised 2,033 peopleFootnote 2 enrolled in courses leading to the Secondary Education Graduate Certificate at a total of 14 AECs in Catalonia. The centres were chosen such that their size, ownership and location would ensure the representativeness of the results. The management of each centre sent a questionnaire by e-mail to the entire study population, regardless of age, to which 234 people responded voluntarily (yielding a sampling error of 6%). This is therefore a non-probabilistic, accidental or convenience sample, as Ruiz (2008) notes, since the subjects were chosen by the fact that they responded.

The size, characteristics and location of the centres ensured the representativeness of the results obtained and their impact in terms of social transfer, since they represented accurately the range of sizes, ownership (municipal and Department of Education), and territorial spread across Catalonia of these centres.

The sample showed a slight bias towards males (51.1% of the sample as opposed to 48.9% of the study population), native inhabitants (78.2% as opposed to 64.3%) and the older age group (mean age 31 as opposed to 29) (Llanes et al., 2022).

2.2 Data collection instrument

A survey in the form of a questionnaire was the tool used to gather data. Its content was validated by experts in the field, including three people from AECs, and piloted amongst a group of students to validate the framing of the questions and their statistical adequacy.Footnote 3

The survey was based on the prior studies reviewed and the analytical models chosen. It included closed Likert-scale questions enquiring into the socio-cognitive variables of the processes of adaptation and persistence in studies, summarised in the following constructs or scales: the level of motivation and attitude towards studies (six measures), the level of satisfaction (five measures, adapted from an original scale by Lent et al., 2009), and the perception of self-efficacy (four measures). To analyse the support received, a single measure was used for the relationship with teachers and another for the relationship with peers. The Cronbach’s alpha values of the scales at the time when participants surveyed were in secondary school and at the time of the study, when they were attending the AECs, are shown below in Table 1. For all participants, the level of reliability of the scales was acceptable (above 0.7).

Some socio-demographic variables that previous studies have found to have a bearing on students’ adaptation to their courses were also considered. In addition to gender, age and nationality, as described above, the parents’ educational qualifications and the employment situation of the students themselves were included (Table 2).

2.3 Procedure

The questionnaire was administered online, with the authorisation of the directors of the centres participating in the study. The teachers invited the students to participate and gave the instructions for completion of the survey during class hours. Since the fieldwork coincided with the period of the pandemic and confinement, a form was designed in Google Forms to facilitate its completion. This was passed on to the management teams of the centres, who administered it. Lastly, SPSS v.27 software was used for processing and analysis.

3 Results

The presentation of results below is divided into two sections. The first explores the levels of motivation, academic satisfaction, self-efficacy and perception of support received at high school and later at the AECs; and the second analyses how these variables are related to students’ intention to persist on their courses, taking into account a range of demographic variables.

3.1 The experience of studying in the AECs

From the analyses of persistence and dropout rates reviewed above, it is clear that knowing students’ motivation for studying, their level of academic satisfaction, their perception of self-efficacy with respect to the programme and the support received from teachers and peers allows us to understand the type of path followed and the decision to drop out or continue. Comparing these factors from the students’ time at secondary school with their appraisal of the same factors during their attendance at the AECs provided a measure of the role the second-chance institutions played in the educational experience of students who had experienced failure and dropped out of compulsory secondary education.

The level of academic satisfaction as one of the factors with the greatest impact on persistence models was analysed both for the period when participants were at secondary school and for the later period after enrolment in courses for the GES qualification. These data allowed us to affirm that there was a significant change in the level of satisfaction, since at the AECs, interviewees stated that they were much more satisfied than they had been at secondary school. All items were between 4 and 5 on a scale of 1 to 5, and higher scores were registered especially when they stated that they felt good in general (4.5) and that they liked the course and enjoyed learning (4.4). This indicated that at the AEC students significantly increased their academic satisfaction in the different measures applied (Fig. 1).

In terms of the perception of self-efficacy, the group’s low self-esteem at school was evident. Their scores did not exceed 3.2 in the different measures. However, after enrolment at the AEC, they saw their confidence and self-esteem increase, particularly feeling much more capable of tackling the tasks given and considering that they were good at the subjects they were studying (Fig. 2).

With regard to the support received from both teachers and peers, they clearly felt they had more support at the AEC than at secondary school, especially when assessing the reception and guidance received from teachers (Fig. 3).

The students’ motivation was clearly stronger during their experience at the AEC than at high school. It was also noteworthy that a higher score was obtained for motivation relating to external factors (to obtain the degree, to have more job opportunities), although more intrinsic motivation such as the desire to improve training and skills should not be disregarded. But what was also noteworthy were the low scores on the measures relating to emotional well-being (feeling accepted and socially connected) during their time at school. This may indicate a problem of social integration, which was seen improve at the AEC, especially in terms of participants’ self-image in relation to the group and their level of integration (Fig. 4).

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test (with a significance level of p ≤ 0.05) corroborated that these were statistically significant differences for all variables, except for the measure titled I was studying for a better future (Table 3).

Given the importance that has been observed in the studies reviewed to the level of satisfaction for motivation and perceived self-efficacy, a principal components analysis (PCA) was carried out to validate the structure of the satisfaction scale and to simplify the information. The analysis revealed a single factor explaining 68% of variance.Footnote 4 The scale means of academic satisfaction for secondary school and for the AECs were 3.2 and 4.4 respectively.

In the following section, we focus on participants’ experience in the AECs. A correlation analysis showed that academic satisfaction correlated moderately and positively with measures of motivation, especially when courses were pursued for motivations centring on enhancement of training and personal skills (intrinsic motives). Satisfaction also correlated strongly with two self-efficacy variables (when the person felt that s/he was good at the subjects and was capable of carrying out the tasks). With regard to support, the greater the perception of support received, the greater the satisfaction, especially when it came to teachers, who showed the highest correlation (Table 4).

3.2 Socio-cognitive factors and the intention to persist

The feeling of well-being and integration at the AECs was clearly greater than at secondary school for this group. In view of the data on repeated dropout and disengagement in adult education, what roles did motivation, satisfaction, self-efficacy and social support play in the intention to persist?

When asked about their intention to persist on their GES programmes, 67.5% of participants answered affirmatively. Figure 5 shows the scores for each measure, according to intention to persist versus intention to drop out. Clearly and without exception, all those who stated that they had some intention to persist had higher scores compared to those who had thought about dropping out at some point.

On performing a Mann–Whitney U test, two of the six indicators of motivation showed significant differences in the intention to persist on the GES: I’m doing it to further my education and improve my skills, and I’m doing it because at the adult education centre I feel accepted. Thus, those with a clear will to persist in their studies were those who were clearer about their educational project, wishing to have more competences and improve their skills, and those who felt more integrated at the centre. For the rest of the scales and variables, the differences were significant, with the exception of peer support. Thus, those who felt more satisfied, more motivated and more confident in their abilities were those who had a clearer intention to continue. Lastly, perceiving greater support from teachers was strongly related to persistence, while peer support was not a facilitating factor when it came to continuing, but neither was it a hindrance (Table 5).

3.3 Personal and family factors

The final factor examined was the influence of the adult education student’s profile on the probability of persistence. A first bivariate analysis was carried out for the variables gender, age, parents’ education, nationality and occupational status. A chi-square test revealed that the only measure with a significant link to the intention to persist in adult secondary education was the student’s employment status (X2 = 14.272, gl = 2, sig. < 0.001). Those who study full-time or who combined studying with working (probably part-time) were those who significantly expressed their intention to continue with their studies (Fig. 6).

3.4 What were the most important factors in the intention to persist at AECs?

The next step was to find out which factors, of those that had showed significant differences in educational trajectories, played the most important roles in the probability of persisting in adult secondary education. To this end, a probability model using logistic regression was designed. The dependent variable represented the probability of persisting in GES versus not persisting. The fit of the model was good, as indicated by the Hosmer–Lemeshow test, and the variability explained by the Y model was 24.2% (see Table 6). The results showed the regression coefficients, the associated statistical significance and the exponential beta.

The logistic regression model revealed that the variables playing a significant role in the decision to persist were the following: the student’s employment situation, the level of academic satisfaction, and self-confidence as a component of self-efficacy. Clearly, the fact of not working or combining a job with studying was what had the greatest influence on the decision to persist. Those who worked had a greater risk than others of disengaging from their studies and ending up dropping out after re-engaging. Next, being academically satisfied with the programme and the centre were clearly a factor in continuity. And lastly, self-confidence also appeared as a very important component of the probability of persisting.

4 Discussion and conclusions

Motivated by the concern for a highly vulnerable group with prior trajectories of failure and repetition in compulsory secondary education, we analysed participants’ educational experiences on entering adult education. To this end, the process of adaptation to the AEC was examined from the perspective of transitions, and the role played by socio-cognitive factors in successful trajectories was investigated.

The first objective was to identify any changes in the levels of motivation, satisfaction, self-efficacy and academic and social support before and after enrolling at the AEC. Our results showed that changing the context brought a new scenario of possibilities for this group of students. They felt better, more motivated and more at ease with their tasks, and had higher self-esteem, all of which are key ingredients for academic success (Huebner & McCullough, 2000; Lent et al., 2017; Vu et al., 2021). They also perceived much more support from teachers, in contrast to the support received at school. Peers, on the other hand, did not seem to be a critical element; this was the factor with the least change in its scores, although it also increased. All this demonstrates the important role played by the AECs as spaces for compensation and inclusion. In a very short time, between leaving secondary school and entering adult education —as can be intuited from the increasingly young profile of the population attending these centres— these students’ attitude towards their studies was transformed. The level of engagement increased, especially in terms of their self-image in relation to the group and their level of integration and well-being at the institution. Consequently, when it comes to people with a history of failure and disengagement from the educational system, access to AECs represents a qualitative leap with respect to secondary school, positively transforming their educational experience.

All these variables also reinforced each other in the case of adult secondary education. Correlation analyses confirmed the high mediating effect of satisfaction with the other variables (Weber & Harzer, 2022). Satisfaction was strongly associated with high study motivation, especially in intrinsic factors. It was also linked to self-efficacy; and lastly, it was associated with the quality of supportive relationships with teachers (Coelho & Dell'Aglio, 2019; Zullig et al., 2011).

This first diagnostic study investigating conditions favouring good performance and continuity in education contrasts with the low success rates in adult secondary education found by the Education Ministry (MECD, 2022), far removed from those registered for compulsory secondary education. Although they start from conditions of well-being and high attachment to the centre, the large scale of these statistics leads us to question their value for the AECs.

This leads to our second objective, which was to determine which variables had the greatest impact on the intention to persist and obtain the adult high school diploma. The first conclusion was that the occupational factor was the most important, in line with studies by Bélanger (2011) and Lister (2007). However, it was not influenced by the parents’ level of education, as argued by sociological studies.

This was followed by socio-cognitive factors linked to satisfaction and self-confidence. Our results concurred with previous research (Brown & Lent, 2015; Magnano et al., 2020): high overall satisfaction with the centre (both socially and academically) increased the probability of persistence. Similarly, self-confidence, as a measure of self-efficacy, was another factor related to the intention not to disengage from education (Schunk and DiBenedetto, 2014), although how these factors are related to each other should be investigated in greater depth to determine the nature of the interaction. It is worth noting that satisfaction and self-efficacy often appeared as deficient or at very low levels in the educational experience of these students at secondary school. Despite this, they were now making up lost ground to strengthen their persistence and achieve the adult high school diploma.

In contrast, teacher support did not seem to have the same impact, as indicated in studies among secondary school populations (Wang & Eccles, 2013); and neither did motivation (Anttila et al. 2022; Vu et al., 2021;). However, in view of the high correlation found between satisfaction and these variables, any initiatives planned from the counselling perspective should avoid disregarding them as important factors. It can be affirmed that advice and guidance from teachers, in accordance with the findings of Lister (2007), Macedo et al. (2011) and Savelsberg et al. (2017), are key factors in students becoming fully aware of their educational and professional life projects. Finding meaning in what one is doing is decisive when it comes to persistence. In contrast, this was not the case with peer support, which did not seem to make a difference in the intention to persist.

The study of persistence and successful pathways through adult education showed points of convergence with analyses carried out at the stage of post-compulsory secondary and higher education. Socio-cognitive ingredients play an important role and are a good starting point for achieving greater attachment and commitment to the educational system on the part of students. But some particularities also emerged that deserve careful attention, such as having a paid job and the insignificant role of peers. As Gravini Donado et al. (2021) remark, this is a complex, multidimensional process in which institutional, academic, social and emotional factors interact and need to be studied in greater depth. It is therefore necessary to undertake further research into the transition processes of adults re-entering the system.

The AECs emerge as facilities for educational inclusion and second-chance instruction that transform young people’s motivations and expectations, often even when they have a long history of school failure. The aim is to ensure that these advantages are maintained and to encourage students’ successful completion of courses. To this end, in these centres, personalised pathways based on tutorial action plans should be devised to boost satisfaction and self-efficacy in academic tasks. Such plans should also be flexible and adapted to their work circumstances, in order to strengthen links with the institution (Affuso et al., 2023; Fraysier & Reschly, 2022; Reschly, 2020).

Finally, one of the limitations of this study that the fieldwork and contact with the centers was carried out in the middle of the COVID confinement, which undoubtedly conditioned the level of participation. Thus, it is proposed to continue this line of research in order to obtain a larger sample of students which would offer greater territorial representativeness and enable us to investigate integration processes and interactions between significant factors in greater depth. These further studies should make it possible to design advice and guidance programmes adjusted to the realities of adult education and to students’ life circumstances. At the same time, this approach should be complemented with a more qualitative one, with the aim to understand the subjective processes that lead to increased engagement and commitment to studying, and to gain insight into the socio-cognitive and relational mechanisms involved.

Notes

Study funded by the Agència de Gestió d'Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca (Catalan Agency for the Management of Aid to Students and Research) under the title “Young People’s Trajectories in Compulsory Secondary Education. Success Factors in Adult Education Centres in Catalonia” (2019 AJOVE 00005). Catalan Youth Agency, Generalitat de Catalunya (Catalan Regional Government).

Students from the academic years 2018–2019, 2019–2020, 2020–2021. In selecting the centres, diversity was accounted for via a range of criteria of representativeness, especially in terms of student profiles and the location of the AEC.

The study was approved by the Bio-Ethical Commission of the University of Barcelona.

The sample adequacy measure KMO, with a value of 0.854, like Barlett's test of sphericity (sig. <0.001), confirmed the appropriacy of continuing with this analysis and summing up the scale in a single factor.

References

Affuso, G., Zannone, A., Esposito, C., Pannone, M., Miranda, M. C., De Angelis, G., Aquilar, S., Dragone, M., & Bacchini, D. (2023). The effects of teacher support, parental monitoring, motivation, and self-efficacy on academic performance over time. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 38(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-021-00594-6

Anttila, S., Lindfors, H., Hirvonen, R., Määttä, S., & Kiuru, N. (2022). Dropout intentions in secondary education: Student temperament and achievement motivation as antecedents. Journal of Adolescence, 95(2), 248–263. https://doi.org/10.1002/jad.12110

Archambault, I., Janosz, M., Olivier, E., & Dupéré, V. (2022). Student engagement and school dropout: Theories, evidence, and future directions. Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 331–355). Springer International Publishing.

Bandura, A. (1999). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 2, 21–41.

Bélanger, P. (2011). Theories in adult learning and education. Barbara Budrich Publishers. http://www.budrich-verlag.de/

Bernardi, F., & Cebolla, H. (2014). Clase social de origen y rendimiento escolar como predictores de las trayectorias educativas. Revista Española De Investigaciones Sociológicas, 146, 3–22. https://doi.org/10.5477/cis/reis.146.3

Bernardi, F., & Triventi, B. (2018). Compensatory advantage in educational transitions: Trivial or substantial? A simulated scenario analysis. Acta Sociológica, 63(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699318780950

Bernstein-Yamashiro, B., & Noam, G. G. (2013). Teacher-student relationships: A growing field of study. New Directions for Youth Development, 137, 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.20045

Breen, R., & Jonsson, J. A. (2000). Analyzing educational careers: A multinomial transition model. American Sociological Review, 65(5), 754–772. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657545

Brown, S. D., & Lent, R. W. (2015). Social cognitive career theory: A theory of self (efficacy) in context. In F. Guay, H. Marsh, D. M. McInerney, & R. G. Craven (Eds.), Self-concept, motivation and identity: Underpinning success with research and practice (pp. 179–200). IAP Information Age Publishing.

Coelho, C., & Dell’Aglio, D. D. (2019). School climate and school satisfaction among high school adolescents. Psicologia: Teoria e Prática, 21(1), 265–281. https://doi.org/10.5935/1980-6906/psicologia.v21n1p265-281

Daza, L., Troiano, H., & Elias, M. (2019). La transición a la universidad desde el bachillerato y desde el CFGS. La importancia de los factores socioeconómicos. Papers, 104(3), 425–445. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/papers.2546

Departament d'Educació. (2009). Decret 161/2009 de 27 d'octubre, d'ordenació dels ensenyaments de l'educació secundària obligatòria per a les persones adultes

DIBA. (2019). Les escoles municipals de persones adultes: Estat de la qüestió. Observatori de Polítiques Educatives Locals.

Elias, M., Daza, L., Troiano, H., & Sánchez-Gelabert, A. (2023). Desigualdad en las transiciones educativas en España. El efecto compensación. Revista Mexicana de Sociología, 85(1), 39–70.

ESREA. (2017). Societat Europea per a la Investigació de Persones Adultes. http://www.esrea.org/?l=en

Fan, W., & Wolters, C. A. (2014). School motivation and high school dropout: The mediating role of educational expectation. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(1), 22–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12002

Fraysier, K., & Reschly, A. L. (2022). The role of high school student engagement in postsecondary enrolment. Psychology in the Schools, 59(11), 2183–2207. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22754

Gorard, S., & Smith, E. (2004) What is ‘underachievement’ at school? School Leadership & Management, 24(2), 205–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/1363243041000695831

Gravini Donado, M. L., Mercado-Peñaloza, M., & Domínguez-Lara, S. (2021). College adaptation among Colombian Freshmen Students: Internal Structure of the Student Adaptation to College Questionnaire (SACQ). Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research, 10(2), 251. https://doi.org/10.7821/naer.2021.7.657

Huebner, E. S., & McCullough, G. (2000). Correlates of school satisfaction among adolescents. The Journal of Educational Research, 93(5), 331–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220670009598725

Konold, T., Cornell, D., Jia, Y., & Malone, M. (2018). Relational climate, student engagement, and academic achievement: A latent variable, multilevel multi-informant examination. AERA Open, 4(4), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858418815661

Lent, R. W., Singley, H. D., Sheu, U. B., Gainor, K. A., Brenner, B. R., Treistman, D., & Ades, L. (2005). Social cognitive predictors of domain and life satisfaction: Exploring the theoretical precursors of subjective wellbeing. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52, 429–442.

Lent, R. W., Taveira, M. C., Figuera, P., Dorio, I., Faria, S., & Gonçalves, A. M. (2017). Test of the social cognitive model of well-being in Spanish college students. Journal of Career Assessment, 25(1), 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072716657821

Lent, R. W., Taveira, M. C., Sheu, H. B., & Singley, D. (2009). Social cognitive predictors of academic adjustment and life satisfaction in Portuguese college students: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74, 190–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2008.12.006

Lister, J. (2007). Persistence. NRDC Research briefing. National Research and Development Centre for Adult Literacy and Numeracy (NRDC).

Llanes, J. (Coord.), Daza, L., Figuera, P., Mallow, D., Marzo, A., Planells, O., Sánchez, I., Soldevila, A., Tey, A. & Torrado, M. (2022). Trajectòries dels i les joves en els estudis de secundària obligatòria. Factors d'èxit als centres de formació d’adults de Catalunya. Col·lecció Análisis nº 7. Observatori Català de la Joventut. Generalitat de Catalunya.

Lodi, E., Boerchi, D., Magnano, P., & Patrizi, P. (2019). High-school satisfaction scale (H-Sat Scale): Evaluation of contextual satisfaction in relation to high-school students’ life satisfaction. Behavioral Sciences, 9(12), 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9120125

López, D., Lister, J., Vorhaus, J., & Salter, E. (2007). Stick with it! Motivating learners to persist, progress and achieve. Year one final report. NRDC Report to the Quality Improvement Agency. QIA.

Macedo, E., Santos, S. A., & Araújo, H. C. (2011). How can a second chance school support young adults’ transition back to education? European Journal of Education, 53, 452–455. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12312

MacLeod, S., & Straw, S. (2010). Adult Basic Skills. Reading: CfBT Education Trust.

Magnano, P., Boerchi, D., Lodi, E., & Patrizi, P. (2020). The effect of non-intellective competencies and academic performance on school satisfaction. Education Sciences, 10(9), 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10090222

MECD. (2022). Sistema estatal de indicadores de la educación. Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional.

Melrose, K. (2014). Annex A: Encouraging participation and persistence in adult literacy and numeracy – literature review. Department for Education. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/683824/Encouraging_participation_and_persistence_in_adult_literacy_and_numeracy.pdf

Orpinas, P., & Raczynsky, K. (2016). School climate associated with school dropout among tenth graders. Pensamiento Sociológico, 14(1), 9–20.

Quigley, A., & Uhland, R. (2000). Retaining adult learners in the first three critical weeks: A quasi-experimental model for use in ABLE programs. Adult Basic Education, 10(2), 55–68.

Reschly, A. L. (2020). Dropout prevention and student engagement. In A. L. Reschly, A. J. Pohl, & S. L. Christenson (Eds.), Student Engagement. Effective academic behavioral, cognitive and affective interventions at school (pp. 31–54). Springer.

Ruiz, A. (2008) La muestra: algunos elementos para su confección. Fitxa metodològica. In REIRE: Revista d’Innovació i Recerca en Educació, 1, 75–88. http://www.raco.cat/index.php/REIRE

Rujas, J. (2015). La Educación Secundaria para Adultos y la FP de Grado Medio: ¿Una segunda oportunidad en tiempos de crisis? RASE: Revista de La Asociación de Sociología de La Educación, 8(1), 28–43.

Rumberger, R. S., & Palardy, G. J. (2005). Does segregation still matter? The impact of student composition on academic achievement in High School. Teachers College Record, 107(9), 1999–2045.

Salvà-Mut, F., Oliver-Trobat, M. F., & Comas-Forgas, R. (2014). Abandono escola y desvinculación de la escuela: perspectiva del alumnado. magis. Revista Internacional de Investigación en Educación, 6(13), 129–142.

Sánchez Guerrero, I., FigueraGazo, P., & Mallows, D. (2020). Retos y oportunidades para los jóvenes en la educación de adultos de Cataluña. Revista Praxis Educacional, 16(42), 240–257.

Savelsberg, H., Pignata, S., & Weckert, P. (2017). Second chance education: Barriers, supports, and engagement strategies. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 57(1), 36–57.

Schunk, D. H., & DiBenedetto, M. K. (2014). Academic self-efficacy. In M. J. Furlong, R. Gilman, & E. S. Huebner (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology in schools (pp. 115–130). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Vorhaus, J., Litster, J., Frearson, M. & Johnson, S. (2011). Review of research and evaluation on improving adult literacy and numeracy skills, research paper no. 61. Department for Business and Skills.

Vu, T., Magis-Weinberg, L., Jansen, B. R. J., Van Atteveldt, N., Janssen, T. W. P., Lee, N. C., Van der Maas, H. L. J., Raijmakers, M. E. J., Sachisthal, M. S. M., & Meeter, M. (2021). Motivation-achievement cycles in learning: A literature review and research agenda. Educational Psychology Review, 34, 39–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09616-7

Wang, M. T., & Eccles, J. S. (2013). School context, achievement motivation, and academic engagement: A longitudinal study of school engagement using a multidimensional perspective. Learning and Instruction, 28, 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2013.04.002

Webb, S. (2006). Can ICT reduce social exclusion? The case of an adults’ English language learning programme. British Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 481–507.

Weber, M., & Harzer, C. (2022). Relations between character strengths, school satisfaction, enjoyment of learning, academic self-efficacy, and school achievement: An examination of various aspects of positive schooling. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 826960. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.826960

Zullig, K. J., Huebner, E. S., & Patton, J. M. (2011). Relationships among school climate domains and school satisfaction. Psychology in the Schools, 48(2), 133–145.

Funding

Study funded by the Agència de Gestió d'Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca (Catalan Agency for the Management of Aid to Students and Research) under the title “Young People’s Trajectories in Compulsory Secondary Education. Success Factors in Adult Education Centres in Catalonia” (2019 AJOVE 00005). Catalan Youth Agency, Generalitat de Catalunya (Catalan Regional Government).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, and draft manuscript preparation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participant

The study was approved by the Bio-Ethical Commission of the University of Barcelona.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Daza-Pérez, L., Llanes-Ordóñez, J. & Figuera-Gazo, P. Exploring the persistence of adults on secondary education courses: occupational status, satisfaction and self-efficacy as key factors. J. New Approaches Educ. Res. 13, 6 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44322-023-00005-2

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44322-023-00005-2