Abstract

This article contributes to the stock of scientific knowledge by showing the effect of orphan status on child labour and school attendance in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). While the abolition of child labour is undeniably one of the major tasks assigned to the International Labour Organization (ILO) when it was founded, child labour remains a severe problem worldwide. In many parts of the world, especially in developing countries, children do not have access to school. Instead of ending up in school, millions of children are forced to engage in child labour in income-generating and non-income-generating activities. Little researchers have yet made it possible to obtain simultaneous information on child labour, school attendance and orphaned children. This paper describes the research that tries to make such a connection. Data used is from the out-of-school children and adolescents (OOSC-DRC-2012) survey organised by the Ministry of Primary, secondary and Vocational Education. Using a bivariate probit econometric model and testing the endogeneity with an instrumental variables approach, funding of the analysis supports the assumption of a significant negative relationship between child labour and school attendance. The result shows also that being orphaned reduces a child's likelihood of school attendance and increases the probability of entering the labour market. It is underlined that most children are present in non-income-generating than income-generating activities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

While the abolition of child labour was one of the major tasks assigned to the ILO when it was founded in 1919 [1], child labour remains a severe concern worldwide [2]. Overcoming the challenge of child labour is crucial to progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals, to which the world is currently committed. Eradication of child labour is considered a primary objective for many scholars [3,4,5,6]. However, children of all ages continue to work in many developing countries. According to the ILO [5, 6], around 152 million children are forced into child labour, with millions of them engaged in hazardous work such as forced labour, commercial sexual exploitation, criminal activities, mining activities, as well as in hotels, etc. Children are generally in dangerous work, whether it is salaried work or unpaid domestic work [6]. According to Adusei [2], the term "child labour" applies to any illegal employment of children under the age of 15 in work that is considered hazardous work. Among the worst forms of child labour, the existing literature cites women and girls’ exploitation through prostitution, and other economic exploitation of children [7, 8], which Bernards [9] identifies as child abuse.

In many circumstances, work interferes with schooling by depriving children of the opportunity to go to or finish school [10, 11]. In these conditions, child labour is usually in conflict with schooling. The existing literature [12, 13] seems to indicate that in the African context, there is a trade-off between child labour and schooling. Many children's rights organisations and anti-child labour campaigns believe that child labour and education are incompatible. They show that child labour is a real obstacle to education for all. Therefore, child labour should be eradicated through the promotion of education [9]. The lack of affordable schools has been shown to encourage the early entry of children into the labour market without any skills [14].

The debate on child labour on school attendance highlights a variety of issues surrounding the causes and consequences of the phenomenon. One of the least explored ramifications to date is the status of orphaned children. Ray [15] shows that the AIDS pandemic is widespread in many African countries, resulting in many orphans. It should also be pointed out that repeated wars in several African countries are responsible for the deaths of many people, leaving behind orphans.

Literature on child labour and school attendance is abundant [9, 16,17,18,19,20,21], however, there remains a gap, namely the link between these two phenomena and orphaned children. Many children are denied the right to attend school and are condemned to work at an early age because their parents are not alive to provide for their basic needs.

This paper answers the following question: what are the connections between child labour, school attendance and orphaned children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo?

Interestingly, nothing is known about child labour, school attendance and orphaned children in the DRC. Hence, the objective of this paper is to fill this gap in the existing literature on empirical investigation of the relationship between these three concepts. We are therefore also testing the trade-off between school attendance and child labour in the DRC.

The economic literature on child labour identifies two approaches associated with this phenomenon [22]. While referring to poverty as a cause of child labour [23], these two approaches have emerged in the way of studying the impact of child labour on the economy. The first approach examines the phenomenon in terms of the cost of consumption. It focuses on the poverty aspect and sees child labour as a means of improving the well-being of the household. This approach is not without limits and is based on a set of questionable assumptions. A second approach explores the trade-off between child work and child schooling [24]. This approach studies the effects of child labour on children’s future well-being. The focus is, therefore, on the cost of investment. It focuses on the role that education may play as a means of getting children out of the labour market, analyses the causes of children's low schooling and the implications of such a phenomenon on the economy.

As Kim [22] has pointed out, the total time available to the child is allocated to two main activities regardless of their time of leisure: work and schooling. The child is considered a labour force and can contribute to the productive needs of the household. In contrast, education is seen as an investment in human capital to increase future well-being and productivity.

Therefore, children’s parents decide on the choice to make between the labour market and formal education. A trade-off between costs and benefits will guide the parental decision provided by child work and the expected gain for child schooling. These costs and profits are direct or indirect; considering that parental decisions are rational [12]. For instance, parents who expect a higher level of income from education investment and their well-being will send their children to school. In comparison, those who expect a lower level of income, and education investment will prioritize sending their children to work. In this case, decisions about having children work conflict with schooling [25]. All the existing literature focuses on parental decision-making. The context in which the child is orphaned has not yet been sufficiently clarified. Few of those studies directly focus on child labour, school attendance and orphaned children [15].

The DRC is a country that has been particularly hard hit by the aversions of war for several decades now. This situation is at the root of the deaths of several million people, especially in the eastern part of the country. This war has led to massive population displacements and has resulted in thousands of pupils dropping out of school, children left to fend for themselves because one or both parents have died, and so on. Hilson [7] also shows that friends can be a motivator for children to participate in daily activities. It should also be pointed out that the education sector in the DRC faces several problems, including inadequate and irregular payment of teachers' salaries, the lack of a pension system, the lack of qualified teachers, etc. These multiple problems affect the quality of education negatively and contribute substantially to children's exclusion from school. Faber et al. [19] focused on the prevalence, forms, and causes of child labour in the artisanal cobalt supply chain and found that poverty and social norms mainly explain why children work in the mining sector, and why such children; mostly boys; are not enrolled in school. Therefore, this paper tests the following hypothesis: there is a negative association between child labour and schooling decisions in the DRC, relying on the results of some empirical studies [12, 13]. Also, orphan status may negatively impact school attendance and positively influence child labour.

Child labour reduces children’s net enrolment rate at both primary and secondary levels. Novella [16] found that there is a negative correlation between the levels of economic activities of children aged between 6 and 14 and the literacy rates of children engaged in full-time work. Children working in rural areas tend to be among the most disadvantaged groups due to the lack of school infrastructure. Economical child labour is more visible in situations of poverty [19, 22, 26,27,28] and the illiteracy of parents. However, ILO [6] thinks that this argument is only valid regarding dangerous child labour. Those authors postulate that, in some contexts, children contribute substantially to the household revenue.

Yet, some children combine both school and work [12, 22]. Nevertheless, there is a criticism that not all child labour is bad [1], that child labour can be compatible with education, and that work can enable learning [2, 29,30,31]. In this perspective, children are considered as a source of income [27]. Parents send their children to work because they can bring money to support the household. Children from low-income families can even pay their school fees by working in their spare time. According to Shafiq [8], some children in developing countries help their family businesses, which allows them to limit costs in the production process. In many cultures worldwide, especially in Africa, children grow up imitating and contributing to the activities of their loved ones, including work. Work is therefore seen as a part of life, and children participate as they grow up to become socially responsible and integrated people. There are cases where children's lives are disrupted by initiatives that prevent them from working. The report of ILO [5] shows that more than two-thirds of working children are unpaid workers in family businesses. Nearly 70 per cent of them are in the agricultural sector, and mainly on family farms. There are social norms that tolerate child labour as pointed out by Adusei [2] and Chamarbagwala [32]. Child labour is also a consequence of social inequalities reinforced by discrimination in several regions around the world. It has been demonstrated that capitalist culture plays a vital role in child labour [33], primarily through the adverse incorporation of children as a vulnerable labour force.

The consequences of child labour are legion and affect many areas of life. Regarding education, most child labourers cannot attend school. By working as children, they are deprived of their freedom to choose their future. From a health point of view, millions of children are subjected to hazardous work [5, 6, 34, 35]. Children may injure themselves with dangerous tools, suffer the consequences of handling toxic substances, and carry heavy loads that interfere with their physical and mental development. Other researchers show that girls who work at a young age are sexually exploited, leading to early pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases [7]. It is therefore argued that child labour is a barrier to children's socio-economic development. These consequences are more observable in developing countries where child labour perpetuates the vicious cycle of poverty [36]. Because most of the time, working children do not finish school, the result is that they end up integrating only low-paying jobs. As adults, they may let their children work at a young age, and later this situation may lead to intergenerational poverty.

Despite the positive results of the past years in eradicating child labour [5], children still work in large numbers in developing countries [7]. Although this problem is not well documented in the DRC, it is a tradition in Africa that children are involved in household chores, which is considered beneficial for their personal development [27]. Even though child labour is generally harmful to children, there are some situations in which children have no other choice but to work. For example, the DRC is one of the countries where schools operate with limited government funding. Therefore, parents pay the school fees so their children can access education. As a result, many children are out of school because of the poverty of their families [19]. Hilson [7] states that the economic consequences affecting children are evident as child labour perpetuates an unskilled workforce with low productivity.

Several econometric modelling of child labour co-exist with school attendance. These methods depend on the parents' decision-making process to send a child to work or to focus on schooling. However, there are circumstances where children can decide by themselves. It is the case, for example, when the parents are absent. Many empirical studies use binary models (logit and probit used by [16, 17], and multinomial models [12, 21, 25, 37], to analyse the probability of a child working or attending school. These methods remain limited because they do not take the interdependence of the child's choice of schooling or work into account. As a result, scholars are increasingly using models to consider the relationship between a child's work and school attendance. The most used models to solve endogeneity issues are bivariate probit [16, 31] and instrumental variables [4, 12, 23, 38]. To consider the interdependence of child work and child schooling, we use a bivariate probit model. The advantage of this model is not only to take into consideration the causality of variables by avoiding endogenous bias but also to study the interaction between child labour and school attendance. The Wald test allows testing the hypothesis of independence between child labour and school attendance. Even though the use of the bivariate probit approach deals with a problem usually known as endogeneity [39] between child labour and school attendance, we also used the instrumental variable method to ensure the robustness of the results. We use data from the out-of-school children and adolescents (OOSC-DRC-2012) survey organised by the Ministry of Primary, Secondary and Vocational Education in the DRC with funding from UNICEF and UNESCO.

The main result shows that child labour is in conjunction with schooling in the DRC. In other words, we find a positive and joint relationship (simultaneity of the decision) between child labour and school attendance. Being an orphan decreases the likelihood of school attendance and at the same time increases the likelihood of child labour. Maternal orphans have a higher probability of not attending school compared to parental. It is underlined that most children are present in non-economic than in economic activities. Also, most children in the DRC work at the same time as they attend school, which means that child labour is a simultaneous phenomenon with school attendance as highlighted by Ray [25]. The issue of child labour is a concern to policymakers because of the early age at which children start to participate in the labour market which prevents them from their childhood and may harm economic growth in the long run.

2 Methodology

2.1 Justification of the econometric model

The head of the household makes a trade-off between child labour and school attendance of its children. Supposing a sequential mode of decision-making is to assume that parents establish an order in the decision-making in terms of child labour and school attendance. Studies show that four decisions are possible [40], either the child only works, or the child goes to school alone, or the child combines work and schooling, or the child does not work and study. It is necessary to postulate extreme assumptions about the parents’ behaviour [21], as there is no clear order between alternatives. The order depends mainly on the motivation of the head of the household, considering Basu and Van’s assumptions. However, there may be situations where parents are not there to make this decision and their absence can certainly influence either positively or negatively both children's work and school attendance.

Using a multinomial logit assumes that all options are independent under the condition of independence of irrelevant alternatives [31]. This seems quite difficult unless one can do confirmation tests beforehand. Methods of estimating simple probit or housing models ignore all forms of correlation that may exist in the choices of schooling and putting children to work. Indeed, the assumption of independence of irrelevant alternatives that are made in the multinomial model is generally not verified in the case of the decision of work and schooling of children [31]. Thus, one of the parametric solutions appears to be the bivariate probit model [39]. As highlighted by Marra et al. [39] bivariate probit approaches control for unobserved confounders by utilising a two-equation structural latent variable framework, where the first equation models a binary outcome as a function of observed confounders and a treatment, or selection, whereas the second equation models a binary treatment or selection process. A bivariate probit model assumes that child labour and schooling attendance are interdependent choices [32]. For this reason, bivariate probit, in the presence of two decisions, has been much more used in the literature [31, 32]. The bivariate modelling of a household decision can be described as follows:

XS and XW refer to the vectors of decision variables, S* and W* the latent variables of schooling and putting to work. S and W represent the observed results taking value one if the decision is made and 0 if not. ρ is the correlation coefficient between the two decision-making processes.

When ρ = 0 means that the decisions are independent. The head of the household faces four choices [28, 37, 40,41,42] depending on whether the child works, goes to school, or does nothing at all.

If schooling and working decisions prove to be interdependent, the head of the household is required to choose one of the two possibilities that ensure the maximum utility of the household. The empirical form of the decision-making process can be described as follows:

where Si and Wj refer to latent variables related to the child’s employment and schooling, respectively. These variables are assumed to be dependent on household characteristics Si and Wj. These two vectors can be of the same size and contain the same variables, although the determinants may vary between the two equations. Random deviations μ are supposed to follow a normal distribution. The results Si = 1 and Wj = 1 refer to the child's choices of employment and schooling, respectively. Si is a binary variable that takes the value one when the child is in school and 0 if not.

Similarly, Wj takes the value one if the child participates in activities that may be related to child labour and zero if not. The model considers Eqs. (3) and (4) as, therefore, a combination of two first Eqs. (1) and (2) probit.

In the decision-making process, the trade-off hypothesis is valid at two levels: an observable and an unobservable level. The observable trade-off is tested from coefficients βi and βj. This type of compromise is observed on a given characteristic z when the coefficients βiz and βjz are contrary signs as demonstrated by Oryoie et al. [28]. The testing unobservable trade-off is equivalent to testing the nullity and the sign of the coefficient, which serves as a link between two equations. When this coefficient is negative and significant, then there is an intrinsic competition or trade-off between the two choices. Where the nullity hypothesis cannot be rejected, both decisions are independent. At the same time, it is enough to estimate each equation by a simple probit.

Nielsen [41] proposes to interpret the coefficient as the parameter indicating the extent to which work increases (decreases) when schooling decreases (increases). This interpretation, therefore, remains valid when is negative. When is positive and significant, it means that both choices are mutually beneficial. There are also other interpretations such as Johnson et al. [42] indicating that the coefficient represents the degree to which the head of the household favours child labour against schooling. Instead, Rosati and Rossi [40] suggest incorporating the notion of opportunity cost into the interpretation of coefficients. From this point of view, the coefficient could, therefore, reflect the level of opportunity cost borne by the head of the household by taking one of the options.

To test these two types of arbitration, in this work, income-generating and non-income-generating activities are considered. The system estimate is implemented by the maximum conditional likelihood inspired by the works of [17, 31, 41]. We assume that human capital is accumulated by sending children to school. The total time children spend at school is limited and fixed (it means that school hours are not flexible, and school attendance requires a minimum fixed amount of time devoted to school). Some of the children who both work and attend school may miss some classes, thus making their school time more flexible. Therefore, the flexibility that can be achieved in this way is limited because skipping school often leads to dropping out [43] and usually is not tolerated by schools [40].

As a rule, the measurement between variables such as “child labour and school attendance” results in an endogeneity bias [4, 23, 38]. The fact that working children may differ from their counterparts who are not in child labour may result in a set of observed and unobserved characteristics. Although a bivariate probit can correct the endogeneity problem [39], the instrumental variable method is the most recommended. This makes it possible to test and correct for this endogeneity bias. If this approach is an effective procedure for dealing with this bias, the issue in practice consists of finding adequate instruments. We therefore use the instrumental variables approach to check the robustness of our results and solve issues related to unobserved characteristics, reverse causality, omitted variables, and simultaneity. By using instrument variables, we estimate the causal effect of the observed variables on the outcome while accounting for the unobserved characteristics. The instrumental variables approach can estimate the causal effect of the treatment variable on the outcome while accounting for selection bias.

2.2 Variables and hypotheses

To determine the impact of each explanatory variable on the likelihood of child labour and/or child schooling, a bivariate probit model is estimated to take the interaction between child labour and schooling decisions into account. Based on empirical studies, this section tries to identify a range of variables that might explain the probability of children working and/or being in school.

Two dependent variables are defined in this study: Child school attendance and Child labour. School attendance is one of the two outcome variables in this paper. The variable that captures child school attendance has been dichotomized, and I have given it the value one for children who are in school and zero for those who are out of school. In the analysis of the interaction between child labour and education, the literature points out the existence of bias of endogeneity during the estimation [17, 31, 42]. The main advantage of this model is that it takes the causality of variables and allows to study of the interaction between child labour and schooling with robust tests into account. The assumption here is that schooling attendance has the effect of removing children from working activities (vice-versa), considering the existence of a trade-off between child work and schooling. The second dependent variable is child labour.

The measure of child labour is far from consensus. The absence of a common methodological framework leads to the impossibility of creating a homogeneous indicator acceptable and usable for all. Scholars guide their methodological choice in the direction of the question studied and take the context into account. Most authors capture child labour in terms of working hours [4, 14, 18, 21, 44].

However, scholars [28, 31, 32, 41] measure child labour using a dummy variable. Thus, child labour takes the value one if the child is involved in income-generating and/or non-income-generating activities and zero otherwise (details of how we captured this variable in Table 9). Based on the limitation of Basu and Van's unitary household model, the child may also be considered a statistical unit. In the rest of the analysis, the variable child labour is subdivided into two dummy variables for children participating in income-generating activities and another for those participating only in non-income-generating activities.

The main control variable is the child's orphan status. Indeed, the fact of having lost one or both parents can influence the child's education. Case and Ardington [45] had already demonstrated that the death of the mother caused a drop in the child's academic results and reduced the child's chance of being enrolled in school. We postulate that orphan status negatively impacts schooling and can lead a child to work. This variable takes the value one if the child is an orphan and zero otherwise. One of the main sources of social and economic disadvantage for children in the DRC is the impact of the decades-long war in the country, which has resulted in the death of many parents. Unfortunately, our database does not contain detailed information on the causes of death of parents, as my repeated political and civil unrest is the cause of death of a significant number of the population.

Several explanatory other variables are selected for this study for robustness check. Most of them are also used in the relevant literature.

-

The age of the child is one of the criteria that defines child labour as mentioned above. While the authors do not agree with the minimum age, it is still true that the age below 15 is used in several types of research to qualify a child [4, 5, 21, 31, 46, 47]. If children aged 15 and 17 can participate in part-time work and work full-time during school holidays, it is forbidden to allow children to engage in work that may negatively impact their future development [5, 20]. This variable is a quantitative one and considers children in the age group of 6 to 17 years. The age of 6 years is retained because in the DRC the school attendance rate is 7 to 14 years.

-

The variable sex of the child is also an essential element in measuring the link between child labour and schooling, especially in developing areas. In Zimbabwe, Oryoie et al. [28] found that boys are more likely to be put to work. ILO [5] highlights, however, the fact that girls would take on a disproportionate responsibility for household chores compared to boys and agrees that sex must be considered in child labour analysis. The proportion of boys involved in child labour (58%) remains higher than that of girls. The reference group is zero for girls.

-

Household composition is cited as a factor that impacts child schooling and child labour [40, 48]. This variable is quantitative and is measured by taking into account the total number of individuals in the household. The milieu of residence is among regressors.

-

The living space has a significant influence on the behaviour of the individual and his/her development. People living in rural zones and those living in urban areas behave differently. This variable is coded one for urban and zero otherwise. In developing countries [47], most of the child labour is in rural areas, especially in the primary sector. The reference category is zero for the rural zone.

-

Household economic status (Hhecostatus) is captured through three categories (poor, middle, and rich households). Several studies have already shown that household economic status is among the factors that influence the decisions of parents in the arbitration between the work and schooling of children [13,14,15, 49]. We postulate that households with low income would send children to work, average households would combine the two decisions, and wealthy households would choose schooling instead of work.

-

Access to electricity is captured as a dummy variable. Access to electricity reduces children's time on income-generating activities and leisure pursuits.

-

Access to water is also chosen as a variable. In the database, this variable is captured in terms of time spent fetching water. We have dichotomised it by considering that those who spend less than a minute in the process of drawing water have access to this commodity and that those who spend more than thirty minutes drawing water do not have access to it. Statistical software Stata version 17.0 was used throughout.

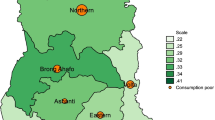

2.3 Data presentation

The dataset used is from the out-of-school children and adolescents (OOSC-DRC-2012) survey conducted by the Ministry of Primary, Secondary and Vocational Education in the DRC. This survey was executed by the Higher Institute for Population Sciences of the University of Ouagadougou (ISSP/UO). OOSC-DRC was financed by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) and technically supported by the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) and the UNESCO Institute for Statistics. This study focuses on two subsamples based on the OOSC-DRC-2012 survey, information from the household questionnaire and information from children aged 5–17 questionnaire. After the data cleaning operation based on the purpose of the study, a sample was selected.

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive statistics

In Table 1, we cross-tabulate child labour with variables such as school attendance, being an orphan of the mother, being an orphan of the father and being an orphan of two parents, and school attendance with being involved in income-generating and non-income-generating activities and being an orphan of two parents. Linking child labour and school attendance shows that 80.19% of children are involved in both child labour and school attendance. In other words, children combine school and work, whether income-generating or not. Only 19.81% of children attend school but do not engage in activities that are categorised as child labour. These figures show that child labour and school attendance are non-exclusive and therefore simultaneous activities. As for the relationship between child labour and orphan status, 3.55% of working children are motherless and almost 9.89% are fatherless. The figures show that children whose mothers have died also have lost their fathers.

As a result, many children are fatherless only. This result is like what Novella [16] found in Zimbabwe, showing that maternal orphans represent the smallest group among orphans. By cross-referencing school attendance, most orphaned children do not attend school. As access to education requires financial means, children who have no one to pay the school fees for them are excluded from school and have no choice but to work. To find out in which activities children are more involved, we separated income-generating activities from non-income-generating activities. 89.52% of working children involved in non-income-generating activities also attend school, while only 6.29% of those involved in income-generating activities also attend school. Adusei [2] points out that children are more likely to work longer hours at home due to the nature of the work such as laundry, cooking, cleaning, looking after children of different ages, and so on; what Savahl et al. [26] qualified as excessive household chores. Statistics show that income-generating activities are a major obstacle to children attending school. Some children indeed finance their schooling on their own in the short term, but in the long term, children may drop out of school because of a taste for money and concentrate entirely on work.

Table 2 is based on the proposed subdivision of working hours proposed by UNICEF [50] to capture the concept of child labour. We separate hours of work by type of activity and by gender. The criterion is proposed to capture child labour by working hours. The principle is that if the child has been doing economic activities in the last week for hours longer than the number of hours depending on his age, this is considered child labour: 5–11 years: 1 h or more; 12–14 years: 14 h or more; 15–17 years: 43 h or more. Overall, in terms of children's working hours, on average, children worked 33.388 h per week with a standard deviation of 6.901. The dispersion around the average is very high as the minimum hour is zero while the maximum is 35 per week. The difference is not significant between girls and boys. This leads us to note that girls and boys worked the same number of hours on average.

The age of the children involved in this study is between 6 and 17 years old. Most children included in this study (around 60%) are aged between 6 and 11 years old. This result means that in the DRC children begin to enter the labour market at a very young age, which is a danger for the future of these children who are not yet physically and mentally strong for work. Analysing the difference between ages considering the sex of the child, the difference is not significant in terms of girls and boys. As much as girls are present in child labour, there are also boys. The other two age groups (12–14 years) and (15–17 years) only represent approximately 40% of the entire sample. The subdivision of the total population into sub-age groups, allowed for meaningful comparisons as noted by Savahl et al. [26]. In fact, child labor does not affect all children equally. If work can lead the younger ones to interrupt school because they cannot combine work and school, the older ones can use the money earned to pay for school fees and other educational needs.

3.2 Econometric results and discussion

To test independence, the sign coefficient and the significance of ρ allow us to conclude whether variables are associated or not. When the coefficient is not significant, despite the sign, the independence between work and schooling is difficult to establish. According to the results in Table 3, child labour and schooling decisions are linked. Coefficient ρ = 0.217 is positive and significant at the 1% level. Therefore, the null hypothesis is rejected, and we conclude that there is a joint relationship between child labour and school attendance. As shown in the bottom of Table 3, the Wald test is significantly greater than zero (160.829) at the 1% level of probability, rejecting the null hypothesis.

Indeed, the significance of the coefficient ρ makes it possible to reject the null hypothesis of independence between the work and schooling of children. There is a positive relationship between the decision to work and the decision to attend school. Based on Nielsen [41], the coefficient ρ in Table 3 is a parameter that indicates that schooling attendance and child labour are joint decisions in the context of the DRC. Indeed, this result reflects the coexistence between child labour and schooling attendance. Each column of tables reports results from bivariate regressions, with robust standard errors in parentheses. Marginal effects are presented. The finding for estimation is in contradiction with empirical findings which found a negative sign of ρ coefficient. Indeed, their result shows a kind of competition between the choice of school attendance and child labour. Unlike the work of [3, 4], our results reject the hypothesis of a possible trade-off between school attendance and child labour and confirm that children combine school attendance and child labour. While this finding is consistent with previous empirical evidence [29] which proposes a flexible education system in Ethiopia to make it easier for children who combine labour market participation and school attendance, other authors have found that child labour remains a serious problem that particularly impacts schooling negatively [2, 4, 7, 20, 21, 48]. Contrary to what our results show, Ray [15] found the existence of a trade-off between child labour and school attendance for both girls and boys in Nepal and Pakistan. Using the rational argument of an economic agent, Edmonds [46] explains that parents decide that their children work because the return to work would be higher than the return to not working. On the other hand, Adusei [2] found in Ghana that most children who combine fishing and schooling generally attend school irregularly. This irregularity in going to school can expose the child to temporary exclusion, with the logical consequence of dropping out in the end. Indeed, in the context of the DRC and Africa in general, it remains difficult to find a child who is not involved in child labour activities. The results show that being orphaned by a mother has a negative influence on school attendance and increases the likelihood of the child working. On the other hand, being orphaned by the father does not influence school attendance, but it does increase the likelihood of the child being involved in child labour. The mother's task is, among other things, to preserve and strengthen the child's physical being, and to free and shape the child's moral being. The mother thus has the most direct and lasting impact on the child's learning and plays a key role in supporting their education. This negative impact may be due to changes in roles within the family: educational choices of children come under the control of themselves. For instance, [36] found that a mother's illness reduces the child's chance of being enrolled in school in Vietnam. Moreover, children might be requested to substitute their absent mothers in household duties. When it is the mother who is involved in her child's education, the child is more committed to his or her schoolwork, stays at school longer and achieves better learning results. This also translates into longer-term economic and social benefits. Although a mother's role in her child's education evolves as the child grows up, it is important to emphasize that in the context of the DRC, the mother plays an undeniable role because she is more present in the home than the father. As our results point out, Case and Ardington [45] found that orphaned children have a high probability of not going to school compared to non-orphans. The mother's attitude to education can both inspire the child and make them responsible for their education. In a country like the DRC, where the major cost of educating children is borne by households, the loss of a parent can have a positive impact on a child's schooling.

Table 4 clearly shows that when a child is completely orphaned, i.e., has neither father nor mother, this increases the likelihood of being involved in child labour and at the same time reduces the likelihood of going to school. The loss of both parents has a direct impact on a child's ability to continue their education, and results in poor access to basic needs. In addition to the trauma that accompanies the loss of parents, early orphanhood exposes the child to a large number of psychosocial risks in the short, medium and long term. The death of the parents, through the drop in economic resources it entails, worsens the child's living conditions because it is associated with serious material deprivation. It is a social risk that can change a child's destiny. The results show that being an orphan has a negative impact on access to schooling. This situation encourages children to enter the labour market at an early age to survive. A child is more likely to drop out of school when he/she does not have a biological father or mother, which pushes him/her to enter the labour market for survival. Studies have already shown that orphans in South Africa are disadvantaged in terms of school outcomes [45]. Thus, the position of the ILO, to abolish child labour at all costs [1] must be taken with a grain of salt since all the causes of child labour have not yet been identified. The total elimination of child labour therefore does not only involve education for all.

In Table 5, the gender of the child is statistically significant at the one per cent threshold. The girl being the reference modality, being a boy in DRC increased the likelihood of working and decreased the likelihood of school attendance.

Similar to Le and Homel [48] finding, there is a significant difference between girls and boys in terms of the time children spend on work and school. This result dovetails with previous research in developing countries, which finds that in the DRC artisanal mining sector, boys are more likely to work in mining activities than girls [9, 19].

The variable age is significant, respectively at one per cent for school attendance and for child labour. The significance of age squared means that an additional year of a child increases the probability of child labour and decreases the likelihood of school attendance. The negative value of the coefficient related to the age squared indicates that the probability increases sharply with age in the early years, then grows less over time, and eventually stops. The results, however, do not tell at what age the probability of working starts to decrease. The fact that the likelihood of a working child increases with age seems reasonable. The older the child, the more his/her physical strength increases. Generally, children mostly perform manual and physical tasks.

According to the composition of the household (household size), the coefficient has a negative sign and is significant at a threshold of one per cent for school but positive and significant for child labour. Therefore, the size of the family decreases the probability of a child to attend school. When the child lives in a household with many children, this situation decreases the likelihood of school attendance. It increases the probability of the child being involved in child labour. Although they are not directly involved in paid activities, some children of advanced age take care of their younger brothers and sisters within the household. Consequently, having siblings decreases significantly at the one per cent level of the likelihood of a child to attend school. Research by Edmonds [18] shows that households with a large number of children discriminate between them, by choosing who to send to school and who to send to work. A household with several schoolchildren may make the selection to know who to send to school or not, due to limited financial resources. The decision of child schooling is, therefore, also a function of the number of heads to be fed. Canagarajah and Nielsen [13] point out that household size is a key element in defining child labour eradication policies. Rosati and Rossi [40] in Pakistan and Nicaragua argue that an additional child in the household could hurt the likelihood of schooling. As in most cases, access to education requires individual costs. Depending on the financial means available, parents may choose among the children, who will attend school and who will stay at home or will work.

The milieu of residence affects positively the probability of school attendance but does not have an impact on child labour. This variable is significant at one per cent for school attendance and child labour. The interpretation is that living in an urban zone increases the probability of school attendance. Indeed, child labour is more pronounced in rural areas than in cities and towns. School infrastructure is insufficient in rural areas compared to what we have in urban areas. This means that some children, despite working, can also attend school in urban areas. Urban children are less likely than rural children to drop out of school. The number of children enrolled in school is lower in rural than it is in urban zones as revealed by the work of Bai and Wang [51] in India. Children who live in towns and cities have more opportunities to attend school because more school infrastructures are concentrated in urban areas. It should therefore be noted that child labour is more pronounced in the agricultural sector.

The household level of income is an important explanatory variable when dealing with child labour and school attendance in a country where most people are reputed to live below the poverty line. A low level of income decreases the probability of a child to attend school. The findings show that, at the one per cent significance threshold, poverty decreases the likelihood of child school attendance while it increases the probability of child labour. In the DRC the income effect is a limiting factor for schooling. Indirect costs associated with schooling can encourage households to send their children to work especially in the informal sector. Those results are completely in line with the initial assumption that child labour would be lower in relatively nonpoor households compared to low-income families [34]. The results found the poverty argument as a primary explanation of child labour must be deeply investigated. Although authors [13, 23, 31], argued that poverty is not only the self-evident reason for child labour, the lower the economic status of a household, the higher the probability for children to be involved in child labour activities. As underlined by Faber et al. [19], in the DRC, poverty is among the main explanations for child labour. This argument is sustained by several scholars, especially those who address the problem of child labour in developing regions [7, 19]. Basu and Van [24] show that child labour leads to a decline in adult wages in the labour market, which in the long run leads to the spread of household poverty. The realities of the DRC where access to education is conditioned by the contribution of parents, the analysis of poverty on the incidence of child labour and schooling should be investigated. ILO [5] argues that educational deprivation is a way in which families experience poverty and is associated with child labour.

To verify the robustness of the sensitivity of the orphan status on child labour and school attendance we successively estimated the bivariate probit model by considering the sex of the child (Table 8) and the subdivision of child labour into income-generating and non-income-generating activities (Table 6). Firstly, an analysis in terms of income-generating activity and non-income-generating activity, concerning education is considered simultaneously. The regression coefficients of the model immediately show the existence of interdependence of three activities (child labour, school attendance and orphan status since the parameter ρ is significant at the one per cent level. Furthermore, the Wald test suggests that the null hypothesis of joint independence of the coefficients must be rejected for the entire model.

We observe that the fact of a child having lost both parents negatively and significantly affects his schooling and positively and significantly his participation in both economic and domestic activities. However, the coefficient ρ does not allow us to reject the hypothesis of no independence between participation in economic activities and the schooling of children. This actually qualifies the previous results and shows that when we separate economic activities from non-economic activities, we find that it is only non-economic or domestic activities that can be simultaneous with the child's schooling.

When we estimate the model according to the sex of the child, we notice that the child's schooling remains an activity combined with work for both girls and boys. The coefficients of ρ are positive and statistically significant respectively 0.192 for boys and 0.213 for girls at the one percent threshold. As we can read in Table 7, being orphaned of both father and mother significantly reduces the probability of the child continuing to go to school, for both girls and boys. This situation also increases the probability of work for boys significantly but not for girls. The results of [36] on the vulnerability of children due to parents’ illness had rather shown that this situation increased the probability of girls being in the labour market and reduced their chance of being enrolled in school.

As no change is observed in the breakdown of the results by sex of the child, the results found remain robust. The previous results clearly show that when parents are not alive, children have a high chance of not continuing to go to school because they have fewer resources devoted to their schooling and this increases their probability of ending up in the labour market. To better understand these effects, we examine whether the probability of work and schooling varies according to the age group of the child (Table 8). We note that orphan status harms the school attendance of children aged 6 to 11 and 12 to 14 for both girls and boys. The education of children in primary school is more negatively affected by the death of their parents than that of their counterparts in secondary school. Also, the fact of being orphaned by both father and mother increases the probability of a child working for the two age groups mentioned above.

On the other hand, orphan status has no effect either on children's schooling or on their probability of participating in the labour market, for children in the age group between 15 and 17 years old. It is therefore clear that the loss of parents affects older children (15–17) much less than younger children (6–11 & 12–14). By subdividing children into age groups, the results now show a negative relationship between school attendance and child labour; for children between 6 and 11 years old. This means that for younger children, there is a trade-off between working and going to school, both for girls and boys. Thus, when you are a child aged between 6 and 11, working reduces the probability of going to school and vice versa. For other age groups, schooling and child labour remain joint activities.

3.3 Robustness check

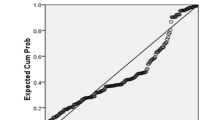

Although the use of the bivariate probit model makes it possible to deal with the endogeneity bias between child labour and school attendance [31, 39], we are not entirely sure that it eliminates this problem. Several authors, however, do not pay particular attention to this issue, even though it can lead to questionable and biased results. The main reason for this is the lack of valid instruments in the databases used. To deal with this problem, the recommended methodology is to use instrumental variables. The use of instrumental variables has thus become a recommended approach for controlling the endogeneity of explanatory variables. Looking at the literature, the average wage of children is one of the best instruments used to test endogeneity. Unfortunately, this instrument is not always available in many databases. It is difficult to measure children's wages, especially in a context where child labour is prohibited. In studies that use cross-sectional data, instrumental variables are included in the child labour equation but excluded in the school attendance one. This exclusion restriction assumes that variations in the instruments are orthogonal. To deal with this difficulty, the authors use proxies. Scholars have used variables such as access to drinking water and access to electricity by Nankhuni and Findeis [12], incomes, assets and infrastructure (radio, telephone, access to water and electricity) by Ray and Lancaster [38], agricultural wages at the community level by Bhalotra [23], the price of rice and disasters at the community level by Beegle et al. [4] as instruments. Most of them find a significant and negative effect of child labour on school attendance. For our study, to resolve the endogeneity bias, we use the instruments used by [38], such as access to drinking water and access to electricity. The lack of basic infrastructure, particularly water, can lead to sanitary constraints for household production activities and, consequently, increase the number of child workers to compensate for the loss of family income. The DRC context shows that access to water and electricity remains a challenge for a large part of the Congolese population. The study by Nankhuni and Findeis [12] showed that in Malawi, the lack of access to electricity for a household can contribute to a heavier workload for children. As a result, children may spend more time collecting resources for cooking. For the results to be consistent and conclusive, certain assumptions regarding the instruments must be respected. The instruments used must not be weak, which means that the correlation between the instruments and the endogenous regressor must not be below a given limit. The suitability of the instruments we use is measured using an over-identification test and the F-test of joint significance (see the bottom of Table 10 in the appendix). Our endogeneity assumption is that these instrumental variables affect school attendance and outcomes only through their impact on child labour and not directly. The result is generally conditional on the validity of the instruments used.

The results in Table 10 show that child labour has a significant negative probability of school attendance. This means that the fact of child labour decreases the likelihood of children attending school. Also, the fact that a child is orphaned decreases without any chance of school attendance, and this is a very significant way. These results support the existence of a trade-off between school attendance and child labour as found by Haile and Haile [31]. Similar to the previous results, being an orphan decreases the probability of school attendance. For the F-test of joint significance, the value must be greater than 10 to confirm that the instruments are strong. Our results show that the F-values are greater than 15 so the hypothesis of a weak instrument is rejected. All relative p-values are less than 10%. Another more important test concerns the validity of the instruments used, which tells us whether the results are reliable. To carry out the instrument validity test, it is recommended to have more instruments than endogenous regressors, which is the case here. As a result, with Hansen’s overidentification test values well above, the test does not reject the overidentification restriction hypothesis, and we conclude that the instruments are therefore valid. The fact that the estimates coincide when two instruments are used indicates that they are robust and that their reliability therefore increases. This means that our results are robust.

4 Conclusion

This study provides a general picture of the effect of orphan children on child labour and school attendance in the context of the DRC. Studies on child labour and school attendance have highlighted the negative relationship between the two activities. Household poverty is cited as one of the main causes that push children to work and cause them to drop out of school. The fact that a child works at a young age harms their development and has long-term consequences on their future as an adult. The absence of parents in the household may be at the origin of the psychological costs. Children who are not accompanied by their parents are generally vulnerable to traumatic outcomes because they lack the emotional support and protection of their adult relatives. This can change the decision-making process within the household, implying a change in duties and responsibilities within the household itself. This situation can also possibly lead children to devote less time to school activities, devoting part of their time to looking for means of survival. Most existing studies assess the relationship between child labour and school attendance, causes of child labour, etc. This article seeks to contribute to the scientific debate on child labour and school attendance by showing that orphan status can impact both school attendance and the child's participation in the labour market in the DRC context. To achieve this, a bivariate probit was used to test the possible link between child labour and school attendance in the DRC, a country where households must pay school fees for children. In addition to a bivariate probit, we test the endogeneity of child labour using instrumental variables to ensure our results are robust. The main result of the analysis is that orphan status negatively influences children's school attendance, increasing the likelihood of children working at a young age. The impact is even greater for maternal orphans than for paternal orphans. This result supports the hypothesis that mothers take more care of their children compared to fathers. The results also show a coexistence between child labour and school attendance. Indeed, many children work, both in income-generating activities and in non-income-generating activities, and at the same time, they continue to attend school. Additionally, the effect of living in a rural environment negatively influences school attendance and increases a child's likelihood of working. The economic situation of the household negatively influences school attendance and leads children to enter the labour market early. Our results argue in favour of greater attention to be paid to orphaned children by public authorities in the DRC. It is therefore important to remember, if children are the adults of tomorrow, to boost economic growth for the country, not placing particular emphasis on orphaned children, especially in terms of their schooling, is a loss of human capital that could lead to long-term costs. Child labour to the detriment of schooling can have serious consequences in terms of future living standards. Therefore, greater educational attainment of both orphaned and non-orphaned children should be properly supported with adequate instruments for the future of children and the future of the national economy.

Since the DRC is one of the developing countries in which artisanal mining exploitation is very developed, child labour could be very pronounced in this sector and may interfere with school attendance; future research can address this issue.

Data availability

The data used in this paper can be freely and openly accessed on https://www.uantwerpen.be/en/projects/great-lakes-africa-centre/national-datasets-livelihoods-drc/national-survey-on-t/

References

Bonnet M, Schlemmer B. Aperçus sur le travail des enfants. Mondes Dev. 2009;37(2):11–25. https://doi.org/10.3917/med.146.0011.

Adusei EK. Child labor and child well-being: the case of children in marine fishing in Ghana. In: Vulnerable children: global challenges in education, health, well-being, and child rights, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6780-9_10.

Coulombe H, Canagarajah S. Child labor and schooling in Ghana. World Bank Economic and Sector Work (ESW), 1999.

Beegle K, Dehejia R, Gatti R. Why should we care about child labor? The education, labor market, and health consequences of child labor. J Hum Resourc. 2009;44(4):871–89. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.44.4.871.

ILO. Global estimates of child labour: results and trends 2012–2016. 2017.

ILO. What is child labour. Stop child labour, no. 182, 2023.

Hilson G. Challenges with eradicating child labour in the artisinal mining sector: experience from northern Ghana. Dev Change. 2010;41(3):445–73.

Shafiq MN. Household schooling and child labor decisions in rural Bangladesh. J Asian Econ. 2007;18(6):946–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asieco.2007.07.003.

Bernards N. Child labour, cobalt and the London metal exchange: fetish, fixing and the limits of financialization. Econ Soc. 2021;50(4):542–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2021.1899659.

Yıldırım B, Beydili E, Görgülü M. The effects of education system on to the child labour: an evaluation from the social work perspective. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2015;174:518–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.697.

Bhukuth A. Le travail des enfants: limites de la définition. Mondes Dev. 2009. https://doi.org/10.3917/med.146.0027.

Nankhuni FJ, Findeis JL. Natural resource-collection work and children’s schooling in Malawi. Agric Econ. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agecon.2004.09.022.

Canagarajah S, Nielsen HS. Child labor in Africa: a comparative study. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci. 2001. https://doi.org/10.1177/000271620157500105.

Beegle K, Bank W, Dehejia RH, Gatti R, Krutikova S. The consequences of child labor: evidence from longitudinal data in rural tanzania subjective wellbeing View project Determinants of consumption measurement View project SEE PROFILE. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/23723534

Ray R. The determinants of child labour and child schooling in Ghana. J Afr Econ. 2002;11(4):561–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/11.4.561.

Novella R. Orphanhood, household relationships, school attendance and child labor in Zimbabwe. J Int Dev. 2018;30(5):725–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3353.

Quattri M, Watkins K. Child labour and education – a survey of slum settlements in Dhaka (Bangladesh). World Dev Perspect. 2019;13:50–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wdp.2019.02.005.

Edmonds EV. Understanding sibling differences in child labor. J Popul Econ. 2006;19(4):795–821. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-005-0013-3.

Faber A, Krause B, Sánchez de la Sierra B, UC Berkeley CEGA White Papers Title Artisanal Mining, Livelihoods, and Child Labor in the Cobalt Supply Chain of the Democratic Republic of Congo Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/17m9g4wm Publication Date. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/17m9g4wm

Hamenoo ES, Dwomoh EA, Dako-gyeke M. Children and youth services review child labour in Ghana : implications for children ’ s education and health. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2018;93:248–54.

Chakrabarty S, Grote U, Lüchters G. Does social labelling encourage child schooling and discourage child labour in Nepal? Int J Educ Dev. 2011;31(5):489–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2010.11.002.

Kim CY. Is combining child labour and school education the right approach? Investigating the Cambodian case. Int J Educ Dev. 2009;29(1):30–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2008.04.007.

Bhalotra S. Is child work necessary? Oxf Bull Econ Stat. 2007;69(1):29–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0084.2006.00435.x.

Basu K, Hoang Van P. The Economics of Child Labor. 1998.

Ray R. Simultaneous analysis of child labour and child schooling: comparative evidence from Nepal and Pakistan. Econ Polit Wkly. 2002;37(52).

Savahl S, et al. The relation between children’s participation in daily activities, their engagement with family and friends, and subjective well-being. Child Indic Res. 2020;13(4):1283–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-019-09699-3.

Folashade D, Omokhodion FO, Omokhodion SI, Odusote TO. Perceptions of child labour among working children in Ibadan, Nigeria. Child Care Health Dev. 2006;32:281–6.

Oryoie AR, Alwang J, Tideman N. Child labor and household land holding: theory and empirical evidence from Zimbabwe. World Dev. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.07.025.

Admassie A. Child labour and schooling in the context of a subsistence rural economy: can they be compatible? Int J Educ Dev. 2003;23(2):167–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0738-0593(02)00012-3.

Meka’a CB, Ewondo Mbebi O. Le travail des enfants : uniquement un problème de pauvreté ? Travail et employ. 2015. https://doi.org/10.4000/travailemploi.6683.

Haile G, Haile B. Child labour and child schooling in rural Ethiopia: nature and trade-off. Educ Econ. 2012;20(4):365–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/09645292.2011.623376.

Chamarbagwala R. Regional returns to education, child labour and schooling in India. J Dev Stud. 2008;44(2):233–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380701789935.

Schuman M. History of child labor in the United States-part 2: the reform movement. https://doi.org/10.2307/90001352.

Kruger D, Soares RR, Berthelon M. Household choices of child labor and schooling: a simple model with application to Brazil. SSRN J. 2007. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.986348.

ILO, Decent work indicators guidelines for producers and users of statistical and legal framework indicators ilo manual second version. Guidelines for Producers and Users of Statistical and Legal Framework Indicators, 2013.

Mendolia S, Nguyen N, Yerokhin O. The impact of parental illness on children’s schooling and labour force participation: evidence from Vietnam. Rev Econ Househ. 2019;17(2):469–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-018-09440-z.

Khan REA. Children in different activities: child schooling and child labour. Pak Dev Rev. 2003;42(2):137. https://doi.org/10.30541/v42i2pp.137-160.

Ray R, Lancaster G. The impact of children’s work on schooling: multi-country evidence. Int Labour Rev. 2005;144(2):189–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1564-913X.2005.tb00565.x.

Marra G, Radice R, Filippou P. Regression spline bivariate probit models: a practical approach to testing for exogeneity. Commun Stat Simul Comput. 2017;46(3):2283–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/03610918.2015.1041974.

Rosati FC, Rossi M. Children’s working hours and school enrollment: evidence from Pakistan and Nicaragua. World Bank Econ Rev. 2003;17(2):283–95. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhg023.

Nielsen HS. Child labor and school attendance: two joint decisions. SSRN Electron J. 2005. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.176068.

Johnson G et al. Entries and exits from homelessness: a dynamic analysis of the relationship between structural conditions and individual characteristics. AHURI Final Report, no. 248, 2015.

Del Rey E, Jimenez-Martin S, Vall Castello J. Improving educational and labor outcomes through child labor regulation. Econ Educ Rev. 2018;66:52–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2018.07.003.

Author P, Ray R. Simultaneous analysis of child labour and child schooling: comparative evidence from Nepal and Pakistan. 2002. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4413018

Case A, Ardington C. The impact of parental death on school outcomes: longitudinal evidence from South Africa. Demography. 2006;43(3):401–20. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2006.0022.

Edmonds EV. Child labor and schooling responses to anticipated income in South Africa. J Dev Econ. 2006;81(2):386–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2005.05.001.

Maconachie R, Hilson G. Re-thinking the child labor ‘problem’ in rural sub-Saharan Africa: the case of Sierra Leone’s Half Shovels. World Dev. 2016;78:136–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.10.012.

Le HT, Homel R. The impact of child labor on children’s educational performance: evidence from rural Vietnam. J Asian Econ. 2015;36:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asieco.2014.11.001.

Edmonds E, Theoharides C. The short term impact of a productive asset transfer in families with child labor: experimental evidence from the Philippines. J Dev Econ. 2020;146: 102486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2020.102486.

UNICEF. Enquête par grappes à indicateurs multiples, 2017–2018, rapport de résultats de l’enquête. Kinshasa, République Démocratique du Congo. mics.unicef.org. 2019.

Bai J, Wang Y. Returns to work, child labor and schooling: the income vs. price effects. J Dev Econ. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2020.102466.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the teams of the "Mardis de recherche" from the University of Mons and the Université Catholique de Bukavu doctoral school who allowed us to present this paper in seminars and conferences to have the current version. We also thank the two anonymous reviewers as well as the editorial team of the journal for their constructive comments.

Funding

We received no funding to produce this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, IMM, DBM, and GV; methodology, IMM; validation, DBM, GV; formal analysis, IMM; investigation, IMM, DBM, GV; resources, IMM; writing—original draft preparation, IMM; writing—review and editing, IMM, DBM, GV; all authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mihigo, I.M., Vermeylen, G. & Munguakonkwa, D.B. Child labour, school attendance and orphaned children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Discov glob soc 2, 8 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44282-024-00029-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44282-024-00029-9