Abstract

This article (Special thanks to the editors of Discover Global Society magazine, Dr. Rajendra Baikady and Dr. Akshay Dhavale, and the anonymous referees for the article) analyzes the impact of technological innovation on occupational integration, using Brazil as a case study. The Brazilian example is evaluated as an illustration of how change promoted by innovation occurs, as well as its effects and consequences for individuals, positions, and occupations. The old and feared possibility of replacing humans with machines is discussed in light of the renewed fear caused by recent developments in artificial intelligence and how they may impact employment in different parts of the world. The study uses cohort analyses, occupational classes, and their respective productive sectors to provide empirical evidence for its arguments. Based on a historical-statistical analysis of a given social space, the study defends the hypothesis that the change resulting from technological innovation in the way goods and services are produced has not increased unemployment. However, it did contribute to the decline of the old middle class and the rise of a new middle class. It was not rural and urban workers who were replaced by machines. Instead, rural and urban smallholders found it difficult to compete with larger organizations that had already established themselves as modern enterprises. These former self-employed or smallholders with few employees changed occupations, and this trend was reproduced in the new generation, leading to a decline in the number of petty bourgeoisie and a concomitant increase in the occupational class called non-manual routine workers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The fear of technology replacing human labor is a longstanding concern [1,2,3,4,5]. The Luddite movements represented one of the greatest oppositions to the use of machines and robots in the production sector. The ongoing shift in artificial intelligence is likely to significantly impact the way production and work are organized in the short term. While some predict a future without opportunities and jobs, others point out that capitalism is in crisis and that technology is paving the way for a post-capitalist society based on collaboration and common ownership. There are also optimistic authors who see technological innovation as an essential driver for capitalist development, just as there are those who see it as a natural factor, the result of the natural competition existing in the capitalist mode of production.

This article has two main objectives, to discuss, with classic [6,7,8] and contemporary authors [9,10,11,12], the possibility of substituting humans by machines and how technology and scientific development affect the social levels of employment. The main research question is whether artificial intelligence will replace human beings in the productive sphere. From a historical-statistical analysis of a particular social space, the article evaluates the hypothesis that the change resulting from technological innovation in the way goods and services are produced has contributed to the decline of the old middle class and the rise of a new middle class. This is because small rural and urban owners found it difficult to compete with larger organizations. Globalization has accentuated this process. The old forms of organization and execution of work, as well as occupational classes, are the ones that have been replaced, not individuals. People migrate, return to their parents' or other relatives' homes, go back to school, look for work alternatives, retire, and die. It is a contradiction, just as it is limited to understand the individual only in their economic aspect, to think that humans are periodically replaced by mechanized machines and/or by the process of automation of production.

Some social anthropologists[13, 14] argue that the advantage of human beings over other species is their adaptive capacity. In the results section, it is shown how this adaptive advantage occurs both in changes of occupational direction (rarer), when individuals change, by will or by external impositions, their work activities, and in changes between generations (more common type), when social change occurs in later generations. It is worth remembering that the educational process of adapting to labor change depends on contributions and investments from different organizations, states, companies, NGOs, and, above all, the families of those affected by unemployment. It would be ideal if there were preventive public policies to welcome individuals at risk of unemployment due to technological motivations.

As this is a competition between different rational agents vying for the supply of a good or service in a non-monopolistic market, the competitive advantage that scientific and technological innovation provides to institutions capable of investing in their technological restructuring is essential to their survival. Like Schumpeter, it is understood that innovation is crucial for the survival of capitalism, but this article takes a different position by recognizing that this innovation is not exclusively the result of organic competition between individuals and institutions. That is, exogenous factors and agents are also crucial in this scenario. The effective action of companies, states, universities, non-governmental organizations, professional investors, donors, and others, to mitigate the problem of unemployment caused by cultural changes in the ways of thinking and executing services and processes, is essential for a faster absorption of the crises arising from constant capitalist changes. Scientific, technological, political, and social changes are outcomes of cultural contestation and innovation movements. The principle of binary opposition between traditional and modern is fundamental in capitalism, as it guides the constant search for innovation. This incessant search for innovation is the main characteristic that distinguishes this mode of production from other known modes, since other modes of productive organization also depend relatively on notions of exploitation, domination and power.

To support the argument that competitive advantage derives from technological innovation, a representative sample study of the Brazilian reality is used as empirical evidence that corporate and sole proprietorship legal entities struggle in the face of competition with large corporations. This is evidenced by the decrease in the number of individuals in occupational positions designated as small rural owners, which includes small farmers, poultry farmers, cattle ranchers, extractives, fishermen, and others, all acting as self-employed or owners in companies with few formal collaborators. Also, the numerical decline of the occupational class of smallholders acting in non-rural businesses, as well as the growth of new occupational classes, such as routine non-manual workers, further supports this argument.

Regarding methodologies, cohort analyses, occupational class analyses, and analyses of productive sectors in which these occupations operate are utilized. The sample is representative of Brazil and evaluates a period in which numerous social, political, and technological changes occurred both in Brazil and worldwide, namely, the second half of the twentieth century. Inter- and intra-generational labor information of individuals is also examined, meaning that changes across generations as well as changes over the life cycle of individuals are examined.

In summary, the article aims to discuss how technological and scientific advancements impact levels of employment and entrepreneurship within society.

2 The theory of mutable capitalism and its foundations in economic thought

The Theory of Mutable Capitalism is based on Joseph Schumpeter's "institutional-evolutionary" approach, specifically his concept of Creative Destruction. According to the theory of loss of competitiveness, machines will not replace humans, but rather certain occupations and functions, as humans are capable of adapting. At each scientific and technological revolution, several individuals and institutions lose competitiveness due to the forces of innovation. Crisis is a moment of adaptation, of learning new practices to generate a new cycle of prosperity. In this theory, capitalism does not enter into crisis due to its inability to generate cycles of prosperity, but rather due to the recent monopolization by some generally private organizations of some form of work or service considered valid (unlimited capitalism thesis), which renders the previous productive way obsolete and costly. The technological revolution modifies capitalism, but it does not revolutionize the capitalist, capital-based mode of production.

Capitalism is an ever-changing and evolving economic system that can be influenced by new technologies, innovations, and social change. Change occurs when a revolutionary technology is developed and socially utilized by some organizations, causing restructuring in certain sectors of the productive way, which requires ongoing learning and adaptation. Schumpeter [15] emphasized the role of innovation and creative destruction in economic development, arguing that capitalism is a dynamic system that is constantly in flux due to the entry of new firms and disruptive technologies that overturn old firms and technologies. Perez [16] proposed the theory of the "great surge" of technological innovation, which occurs in cycles of sixty to seventy years. She argued that these surges are driven by changes in technological infrastructure and that each surge leads to a new phase of economic development. Christensen [17] coined the term "disruptive innovation" and argued that companies must be able to adopt new technologies and business models to survive in a constantly evolving market.

The term "mutable capitalism" describes the idea that the capitalist system is inherently resistant to change and cannot be fundamentally transformed. Proponents of this view argue that the changes that occur in capitalism are superficial and do not affect the fundamental nature of the system. This view is more commonly held by critics of capitalism. Karl Marx emphasized the importance of class struggle and collective action in transforming the economic and social structures of the capitalist system. Karl Marx's contribution in The Capital [18] is fundamental for the reader to understand the classical basis of the discussion presented in this article, as well as the later reproductions of Marxian thought and the criticisms that arose from it. Authors such as Émile Durkheim, Max Weber, Joseph Schumpeter, among others, used Marx's sociological and economic analyses as a starting point for their own reflections, whether to criticize them, reuse them or give them a new guise.

Specifically in the chapter "The Revolution Operated by Capital in the Mode of Production", Marx addresses three central questions which are fundamental in the construction of Durkheim's concept of Organic Solidarity, although Durkheim does not cite Marx; just as for Max Weber's development of "The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism", also for the interpretation of capitalism proposed by Schumpeter, just as these questions are fundamental for the interpretation of the arguments, results and conclusions of the present article. The issues are (a) the question of cooperation; (b) the specific problem of cooperation in the capitalist mode of production, including the division of labor in the manufacturing mode of production; and (c) the question of mechanization and big industry. According to Marx, collective cooperation at the beginning of capitalism was voluntary, but became compulsory when it was no longer possible, with the advent of machinufacturing (the first industrial revolution), for small artisans and small landowners to compete with the large capitalist corporations (Additional file 1).

It is also in this chapter that Marx defines the concept of Capitalism:

As the collaboration of a large number of workers, working simultaneously and in the same place, or in the same field of labor), in a constant manner, ordered by the same capitalist, with the aim of producing the same type of commodity. Capitalist production begins when the same individual capital employs a significant number of workers and the labor process expands, allowing the production of large quantities of products.Footnote 1

The simultaneous employment of many wage earners in the same labor process therefore constitutes the starting point of capitalist production.Footnote 2This is the first alteration undergone by the real labor process due to its subordination to capital.Footnote 3Cooperation is called this form of labor in which many workers labor side by side or together, according to a general plan, in the same process of production or in different but related processes.Footnote 4Co-operation in the labor process in the beginnings of civilization is based on the one hand on the common ownership of the conditions of production, and on the other on the fact that the individual is as closely linked to the tribe and the community as the bee to the hive.Footnote 5

It is distinguished from capitalist cooperation by these two characteristics. The sporadic, large-scale employment of co-operation in the ancient world, in the Middle Ages and in the modern colonies, is based on immediate relations of domination and servitude, and almost always on slavery.Footnote 6

The capitalist form, on the contrary, supposes first of all the existence of a free wage-earner, who sells his labor-power to capital.Footnote 7Capital has the immanent instinct and permanent tendency to increase the productive force of labor, in order to lower the price of commodities and therefore that of the worker himself.Footnote 8 The capitalist form centered on accumulation and profit, needs the production of labor to be collective in order to decrease the final value of the merchandise, such as the value paid to the wage earner. The incessant search for the maximization of time and money often results in the pauperization of the worker and the adoption of a disposable vision in relation to human beings.

Marx divides capitalism into two phases, the manufacturing phase (beginning) and the machinofactory phase (maturity). In the manufacturing phase, the mode of production differs from the industry of trades guilds in that it occupies a large number of workers with the same capital.Footnote 9

Thus, at first there is only a quantitative difference. However, within certain limits a substantive change is produced. In all branches of industry, the individual worker, João Bras or Marcelo, differs more or less from an average worker. But these individual divergences compensate for each other and disappear as soon as an expressive number of workers is assembled.Footnote 10

The English writer Edmond Burke (1729-1797), basing himself on his own experience as a caretaker, asserts that in so small a group as the group of five ploughboys, any individual difference in work disappears, and that five adult ploughboys, whatever they may be, perform in the same lapse of time as much work as any five others taken at random.Footnote 11

He continues:

Just as the offensive force of a cavalry squadron or the defensive force of an infantry regiment differs essentially from the offensive or defensive forces employed by each cavalryman or each infantryman, so the sum of the mechanical forces of isolated workers differs from the social force which develops when many arms collaborate simultaneously in the same undivided operation, when it is a matter for example of lifting a bale, turning a crank or pushing aside an obstacle.Footnote 12

So that, as the performance of work in a collective way becomes an imperative in modern, capitalist societies, most individuals are forced to sell their labor power to some capitalist, given the difficulty of competing with the large industrial corporations. Thus, Marx anticipated the decline of the petty bourgeoisie, as well as the classes referring to small rural and urban landowners.

In the manufacturing period the collective worker is still the very mechanism of labor.Footnote 13

Since professional skill remains the basis of manufacture and the total mechanism which functions in it has no material structure independent of the workers, capital constantly struggles against the insubordination of the workers.Footnote 14

Marx also discusses in the chapter cited the impact of the introduction of machines in production and argues that it is at this moment that it becomes possible to speak of an industrial revolution. It is at this moment that he differentiates a machine from a simple tool, arguing that while tools are an extension of the human being, machines operate autonomously.Footnote 15 So that, machines are created to increase productive efficiency, as to decrease the final cost of goods, however it is also a way to replace human labor.

One of the most perfect creations of manufacturing capitalism was the workshop in which the instruments of labor are manufactured, above all the complex mechanical devices already in use at that time. This workshop, a product of the manufacturing division of labor, performed by all in the same service environment, produced in turn the machines. Thus, the barriers that the dependence of labor on the personal abilities of the worker still opposed to the domination of capital disappeared. In manufacturing, the starting point of the revolution in the mode of production is the labor power; in big industry, it is the means of labor.Footnote 16

The machine is distinguished from the instrument of labor, as soon as the real tool which acts on the raw material passes from man to a mechanism, the machine replaces the simple tool. The revolution in the mode of production of industry and agriculture notably made necessary a revolution in the general conditions of the social process of production, in the means of communication and transport.Footnote 17

The machine-tool, which serves as the starting point of the industrial revolution, replaces the worker, who handles one tool only, by a mechanism which works simultaneously with a number of tools working identical or analogous and is moved by a single motive force, the assembly of all these simple instruments, set in motion by a single engine, constitutes a machine - Babbage, London, 1832.Footnote 18

While professional skill is fundamental in the period of manufacturing, due to the need to handle the tools, seen as an extension of the human hand, this ceases to be significant in the age of the machinofactory.Footnote 19 Thus, the notion that human labor is perfectly replaceable stems both from the change in the form of production—which ceased to be individual and autonomous to be eminently collective, for the sake of rationality and profit—and from the change in the mode of production made possible by the machinofactory, during the first industrial revolution.

Max Weber [19] argued that capitalism is based on a logic of rational-legal domination that tends to perpetuate existing power structures. Thorstein Veblen [20] emphasized the importance of class distinction in the dynamics of the capitalist system and argued that conspicuous consumption was a way of demonstrating social status within the capitalist system. In this regard, similarities can be found between Veblen's ideas and those of Marx and Weber, such as the notion of the perpetuation of relations of domination that occur through the transmission of class and status.

Schumpeter's vision is positive in relation to capitalism, as he sees it as functioning similarly to how Karl Popper [21] understood the functioning of science, not as an accumulation of knowledge and theories, but as a true principle of the substitution of one paradigm for another. This means that the success of one entrepreneur or company represents the selective failure of others who are less competitive. The concept of Mutable Capitalism [22,23,24] recognizes that the capitalist system is constantly changing and adapting in response to changes in the economic, social, and technological environment, giving rise to different phases of capitalism. While there is divergence among authors, the following phases of capitalism can be identified from the perspective of Mutable Capitalism.

There have been different phases of capitalism throughout history. The first one was Commercial Capitalism, which began in the Middle Ages and focused on trade and colonies. Then came Industrial Capitalism during the Industrial Revolution, where companies used machines to mass-produce goods. Financial Capitalism followed, where banks and investors lent money to companies for growth. State Capitalism started after World War II when governments became more involved in regulating the economy. In the 1970s, neoliberal policies became popular, advocating for the reduction of state intervention in the economy. Later, Information Capitalism emerged with the expansion of the internet and new technology. These phases demonstrate how the economic system adapts to changes, and businesses need to innovate and adapt to succeed. The phases of capitalism demonstrate the constant adaptation of the economic system to changes in the environment, and how these changes affect business and society in general. Mutable Capitalism recognizes the importance of innovation and adaptation for the survival and success of businesses in this ever-changing environment.

Creative Destruction is a concept introduced by economist Joseph Schumpeter, which refers to the constant destruction of old industries and companies and the creation of new ones, as part of the process of economic evolution. According to Schumpeter, innovation is the engine of economic growth and is driven by competition and the constant search for new market opportunities. The concept of adaptation can be defined as the ability of an organism or system to adjust to the environmental conditions in which it finds itself, to maximize its survival and reproduction. Adaptation is an evolutionary process that can occur at both the individual and population levels and is fundamental to the survival of species in ever-changing environments. Among some concepts coined by Park [25], the idea of Ecology has a different meaning from the current one. Influenced by Darwin [26], Durkheim [27], and especially by a quantitative and qualitative empirical approach, it states that individuals compete for resources and for space.

Another central concept used is Revolution, which represents an economic and social rupture in the mode of productive organization, as understood by Karl Marx. The technological revolution does not cause the downfall of capitalism because it is fostered by it. Capitalism lives on scientific and technological innovation, so all changes and even technological revolutions are appropriated by this mode of production. It is understood that the technological revolution is possible thanks to the capitalist ethic of the search for continuous innovation, which is the main strength of this mode of production.

3 Impact of automation and robotics on employment: perspectives and challenges

There is a variety of articles examining the employment implications of automation technologies. Some suggest that robots and other machines can replace human workers in certain tasks, while others argue that these technologies can complement human labor, increasing productivity and creating employment opportunities. Wang et al. [28] examined the impact of robot adoption on firm innovation in China and demonstrated that robots can improve innovation in manufacturing firms. Meanwhile, Huang et al. [29] analyzed data from several Chinese companies and found that robot adoption is associated with increased productivity. However, the impact of robot adoption varied between different types of industries and company sizes. In a review of the literature on automation and employment, Filippi et al. [30] suggest that the impact of automation on jobs depends on the institutional context and the nature of the tasks involved.

Hertog et al. [31] estimated the effects of automation on time spent on housework and care work in Japan and the United Kingdom, showing that automation can reduce the time devoted to these activities. Ferreira et al. [32] discuss the implementation of Industry 4.0 in manufacturing multinational enterprises and highlighted the importance of environmental and social sustainability in this process. Other articles focus on topics such as the love-hate relationship between technology and successful aging at work [33], the relationship between works councils and firms’ further training provision in times of technological change [34], and assessing alternative occupations for truck drivers in an emerging era of autonomous vehicles [35].

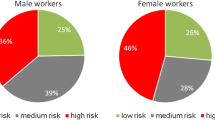

The increasing use of automation and technological advances has raised concerns about the future of employment. According to information from the OECD, Arntz et al. [36]. conducted a comparative analysis of this risk and found that approximately nine percent of jobs in OECD countries are fully automatable, while another twenty-five percent are at risk [36] of significant changes in the way they are performed. In a later study, Arntz et al. reviewed the risk of automation and found that the proportion of jobs at risk had slightly decreased due to changes in the tasks performed by workers.

Bakhshi et al. [37] examined the impact of automation on the creative economy and argued that automation is not a significant threat to this sector as machines are not yet able to replicate human creativity. On the other hand, Bessen [38] took a different approach in his study, suggesting that automation could actually boost employment. He argued that automation can lead to the creation of new jobs and increase productivity, which can result in economic growth and job creation.

4 The process of substitution and capitalist crises

When a productive way is replaced by other form, a period of social instability ensues, which can culminate in economic crises. The crisis occurs because of the contradictions brought about by social and technological changes, especially in terms of the inequalities generated during times of change in social organization. Initially, a few corporations dominate and monopolize new techniques or methods of work, which provide an advantage over the old productive way for the same service. However, as the entire social organizational structure is modified, many companies are not able to survive the intense technological and social changes.

The technological change achieved by some organizations may lead to a rupture in the stable production chains until then, when a simpler, cheaper, and more accessible way of doing things comes into existence, which modifies the economic and social distribution of resources, often leading to concentration without the intensive action of the State. The exchange of the right to work for the right to consumption becomes problematic, as consumption mostly comes from work, and few are rent-seekers or large owners of the means of production. As some trades and labor activities are modified, the chains that were previously constituted are dismantled, and the company that developed certain technology appropriates all the wealth that was initially in a speculative and symbolic state. As a business group has a monopoly, at least at the beginning, on the constitution of an activity or service, it grows rich at the expense of other business societies, which become outdated, and the people who lived from these activities are often forced to change their lives.

Corporations that innovate an activity, a way of doing a service, or a job, promote a change that makes various forms of work, activities, and services obsolete. The change in the offer of services puts at risk the companies that offer this service with less efficiency. The crisis also arises because the shares of old companies lose liquidity in a short space of time, as well as because of the lack of liquidity of banks and financial institutions when individuals redeem or seek to redeem their capital at the same time, and especially because of the widespread default of individuals and companies in debt. A social crisis, triggered by significant technological change, leads to a breakdown of confidence in the banking system, which can offer nothing but securities and promises of payments of pecuniary values, all speculative. Since banks act speculatively, and thus make fortunes, should a situation arise in which their former creditors simultaneously withdraw or attempt to withdraw their expectations of income or some form of real capital, such as specie, and these bank creditor agents discover that the financial institution, an agent that moves both the money of the capitalist, the worker, the State, and the Third sector, has filed for bankruptcy. This is a common situation in moments of capitalist crises. Their alibi for what has happened (to the bank) is that they were asked by the This leads to the problem of the absence of liquid assets to cover all the simultaneous obligations.

On the other hand, the capital of the new capitalist, the revolutionary, also exists initially, in its beginnings, as speculative capital. After all, nobody has a crystal ball to know if the states or other agents, like social movements, will act to curb the new technology, which would result in a high speculative investment for nothing if it is prohibited, for example. Although history shows us that scientific and technological revolutions usually prevail over state protectionism, this may take some time, and time is money [39], just as time is life. The new productive form is speculative, but which, however, may have already caused the collapse of the old productive form. The public discovery of the technological revolution leads to a state of generalized distrust about the recently old ways of executing some tasks and activities. When the technological revolution is in fact assimilated by most nations, it results in the extinction of an entire niche market, causing an economic and social crisis in those markets anchored in this fictitious system of profit maximization.

The loss of competitiveness of small businesses in capitalism has contributed to the shrinking of the old middle class and the rise of a new middle class. This is because urban and rural smallholders have found it difficult to compete with larger organizations, and globalization has accentuated this process.

While technology does not completely replace workers, it can lead to job losses in sectors that have become obsolete due to automation and digitalization. However, technology also creates new opportunities in other areas, sectors, and occupations, which can be seized by both new and old generations. This process is known as "creative destruction," a concept introduced by Schumpeter, which means that innovation takes old players out of the game but at the same time creates new opportunities and new players. It is important to find ways to support small businesses and workers who are affected by technological change by encouraging small domestic producers to innovate and develop new sectors and employment opportunities. The only way for small businesses to compete with larger organizations in a globalized and networked market is through subsidies and incentives from national governments.

5 Results

We have used data from the 2008 Social Dimensions of Inequality Survey to present a division by cohorts (25–35|36–45|46–55|56–64), occupational sectors, and occupational classes, the latter based on the class scheme of Goldthorpe, Erikson, and Portocarero [40], which analyzed the process of social change in two distinct generations (Parents-Children) (Tables 1 and 2). The results of both sectoral and class analysis indicate that Brazil has undergone a significant change in its work and employment organization. However, the rural worker has not lost his job to the machine in the last fifty years, nor has the industrial worker been replaced, as he has been open to technological changes. Instead, the loss of competitive power of small rural producers and the difficulty of the small businessman or autonomous worker to compete with global capital companies have been observed. It is noteworthy that it was not the workers in these sectors who were replaced but the small enterprises. The explanatory hypothesis is the difficulty of competition of the small with the big capitalist, who is increasingly influenced by innovation, as defended by Schumpeter with the notion of Creative Destruction, in which Capitalism destroys those who cannot innovate.

It is also interesting to note that the State, in all its spheres, is one of the largest employers in Brazil, accounting for more than a third of the entire employed population. The employment/unemployment situation in Brazil for the following cohorts (25–35|36–45|46–55|56–64), respectively, was 40/60, 63/37, 74/26, 74/26. The conclusions presented are reinforced by the results of Barnichon and Matthes [41], which suggest the existence of a natural rate of unemployment that has been remarkably stable throughout history, oscillating between 4.5% and 5.5% for long periods, including during the Great Depression. Therefore, the jobs lost due to innovation are generally replaced in other sectors, creating a dynamic economy, as advocated by Schumpeter. In such an economy, the collapse of old classes may occur before the rise of new groups, which can create a social vacuum that contributes to the perpetuation of crises. However, it is important to note that technological innovations have a variable social impact, and the capacity to absorb these changes may be greater in the twenty-first century compared to the late 19th and early twentieth century.

The pessimistic view in relation to technological advances points to the possibility that man will be replaced by the machine in the near future. However, analysis of employment rates over the last hundred years suggests that this prediction is unfounded. In fact, human employment has remained stable over time.

6 Conclusion and discussion

This article analyzes the impact of technological innovation on occupational integration, using Brazil as a case study. The Brazilian example is evaluated as an illustration of how change fostered by innovation occurs, as well as its effects and consequences for individuals, positions, and occupations. Technology is viewed, in this study, as a normal part of a cycle or process that Schumpeter called the Life Cycle of Capital, which is neither a threat nor a panacea for all human problems. The old and feared possibility of replacing human beings with machines is discussed in light of the renewed fear caused by recent developments in artificial intelligence and how they may impact employment in different parts of the world. The study utilizes cohort analyses, occupational classes, and their respective productive sectors to provide empirical evidence for its arguments. Based on a historical-statistical analysis of a given social space, the study defends the hypothesis that the change resulting from technological innovation in the way goods and services are produced has not increased unemployment. However, it has contributed to the decline of the old middle class and the rise of a new middle class. It was not rural and urban workers who were replaced by machines. Instead, small rural and urban owners found it difficult to compete with larger organizations that had already established themselves as modern enterprises. These former self-employed or smallholders with few employees changed occupations, and this trend was reproduced in the new generation, leading to a decline in the number of petty bourgeois and a concomitant increase in the occupational class called routine non-manual workers.

The debate about job displacement by machines considers the importance of a fair transition and the need for public policies to protect workers affected by automation. Occupational reintegration public policies can target the petty bourgeoisie, which is generally the class most affected by technological innovation. It is crucial to recognize that technological change can bring challenges and require social adaptation. In this sense, it is possible that some occupations will be transformed or even become extinct, but this does not mean that human employment is in danger. However, people need the assistance of various agents, such as companies, governments, non-governmental organizations, among others. The central conclusion is that humans will not be replaced by machines, nor by intelligent machines capable of learning, at least according to recent capitalist history.

Notes

Marx, K. O Capital, p. 47.

Ibid.

Ibid, p. 54.

Ibid, p. 48.

Ibid, p. 53.

Ibid, p. 53–54.

Ibid, p. 54.

Ibid, p. 46.

Ibid, p. 47.

Ibid, p. 47.

Ibid, p. 47.

Ibid, p. 48–49.

Ibid, p. 61.

Ibid, p. 68.

Ibid, p. 61.

Ibid, p. 69.

Ibid, p. 72.

Ibid, p. 71.

Ibid, p. 61.

References

Butler SE. London: Trübner & Co., 1872.

Wells HG. The time machine. London: William Heinemann; 1895.

Huxley A. Brave new world. London: Chatto & Windus; 1932.

Mumford L. Technics and civilization. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company; 1934.

Ellul J. The technological society. New York: Vintage Books; 1964.

Smith A. An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. Londres: W. Strahan and T. Cadell, 1776.

Ricardo D. Principles of political economy and taxation. London: John Murray; 1817.

Marx K. Capital: critique of political economy, vol. I. Hamburg: Verlag von Otto Meissner; 1867.

Frey C, Osborne M. The future of employment: how susceptible are jobs to computerization? Technol Forecast Soc Chang. 2016;114:254–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.08.019.

Ford M. Rise of the robots: technology and the threat of a jobless future. Basic Books, 2015.

Graetz G, Michaels G. Will robots take our jobs? a review of the evidence. Ann Rev Econ. 2018;10:1–20.

Bostrom N. Superintelligence: paths, dangers. Strategies: Oxford University Press; 2014.

Kroebe, A. O superorgânico. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2015.

Boas, F. The mind of primitive man. New York; Macmillan, 1911.

Schumpeter J. Capitalism, socialism and democracy. New York: Harper & Brothers; 1942.

Perez C. Technological revolutions and financial capital: The dynamics of bubbles and golden ages. Edward Elgar Publishing, 2002. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781781005323

Christensen CM. The innovator’s dilemma: when new technologies cause great firms to fail. Brighton: Harvard Business Review Press; 1997.

Marx K. O Capital. Lisboa: Edições 70, 1979.

Weber M. A Ética Protestante e o Espírito do Capitalismo. Rio de Janeiro: Companhia das Letras; 1904.

Veblen T. The theory of the leisure class: an economic study of institutions. New York: Macmillan; 1899.

Popper K. The logic of scientific discovery. Translated by Octanny Silveira da Mota and Leonidas Hegenberg. São Paulo: Editora Cultrix, 2000.

Polanyi K. The great transformation: the political and economic origins of our time. Boston: Beacon Press; 1944.

Bell D. The coming of post-industrial society: a venture in social forecasting. Basic books, 1973.

Harvey D. The condition of postmodernity: an enquiry into the origins of cultural change. Blackwell, 1989.

Park RE. Human ecology. Am J Sociol. 1936;42(1):1–15.

Darwin, C. A Origem das Espécies. São Paulo: Hemus – Livraria Editora Ltda.

Durkheim É. As regras do método sociológico. São Paulo: Martin Claret; 2001.

Wang X, Zheng Y, Zhang Q, Li Y. Robot adoption and firm innovation: evidence from China. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2023;173:121201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121201.

Huang Y, Luo D, Zhang T. How does robot adoption affect firm productivity? Evidence from Chinese firms. Int J Prod Econ. 2023;240:108359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2021.108359.

Filippi M, Robb R, Seabrooke L. Automation and employment: a review of the literature. Socio-Econ Rev. 2023;21(1):139–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwz039.

Hertog E, Robb R, van der Zwan N. Automation and the future of housework and care work: Insights from two empirical studies. Gender Work Organ. 2023;30(1):63–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12634.

Ferreira JJ, Lopes JM, Gomes S, Rammal HG. Industry 40 implementation: Environmental and social sustainability in manufacturing multinational enterprises. J Clean Prod. 2023;311:127785.

Pak K, Renkema M, van der Kruijssen DTF. A conceptual review of the love-hate relationship between technology and successful aging at work: Identifying fits and misfits through job design. Hum Resour Manage Rev. 2023;33(1): 100849.

Lammers A, Lukowski F, Weis K. The relationship between works councils and firms’ further training provision in times of technological change. Br J Ind Relat. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjir.12549.

Wang S, Mack EA, Van Fossen JA, Savolainen PT, Baker N. Assessing alternative occupations for truck drivers in an emerging era of autonomous vehicles. Transp Res Interdiscip Perspect. 2023;13: 100499.

Arntz M, Gregory T, Zierahn U. The risk of automation for jobs in OECD countries: a comparative analysis. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2016. (OECD Social, Employment, and Migration Working Papers, n. 189).

Bakhshi H, Frey CB, Osborne M. Creativity vs. robots: The creative economy and the future of employment. London: Nesta; 2015. https://media.nesta.org.uk/documents/

Bessen, J. Automation and jobs: when technology boosts employment. No. 17-09 Boston University School of Law, Law and Economics Research Paper 2018. https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/faculty_scholarship/815.

Franklin B. Poor Richard's Almanack. Philadelphia: Benjamin Franklin, 1757.

Goldthorpe JH, Erikson R, Portocarero L. The social grading of occupations: a new approach and scale. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1979.

Barnichon R, Matthes C. The phillips curve: a new deal era relic. FRBSF Econ Lett. 2017. https://doi.org/10.24148/epl2017-23.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AF wrote the manuscript alone, every step of the way. The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Fig. S1.

Scientific theory of substitution. Table S1. Digital domination index.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Freitas, A.A. The impact of technological innovation on occupational insertion: a case study in Brazil. Discov glob soc 1, 2 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44282-023-00002-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44282-023-00002-y