Abstract

Coastal mangrove-dependent communities face various risks due to climate change, thus rendering them vulnerable. This study explored the vulnerability of these communities in the Tana Delta in Kenya using an indicator-based vulnerability assessment framework to better understand their exposure, sensitivity and adaptive capacity. Data was collected through household surveys (n = 377), focus group discussions (FGDs), and key informant interviews (KIIs). The analysis revealed mean vulnerability indices at the sub-location level ranged from 0.850 for Kipini to − 0.913 for Kilelengwani and − 2.702 for Ozi. The statistically significant indicators of vulnerability were (i) exposure—high temperatures and rainfall changes; (ii) sensitivity—household numbers, head of household’s age, dependents’ education, and dependents’ employment; and (iii) adaptive capacity—ownership of assets, access to community infrastructure and services, condition/quality of houses, total income, and alternative sources of income. The findings highlight the need for adaptation strategies that ensure greater financial assets supported by education and skills enhancement to utilize existing opportunities. Attention to community infrastructure and services is crucial. Policy should focus on financial, physical, and human assets to reduce community vulnerability alongside the continued conservation and management of mangrove resources. The results will help policymakers in addressing the impacts of climate change and benefit households in the study area. These insights can be applied to regions with similar climate conditions and livelihood systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Global climate change is increasing the occurrence of floods and droughts. The frequency and intensity of extreme weather events and rising sea levels are on an upward trajectory and are anticipated to continue rising [1]. The ecosystems most sensitive to these disturbances include forests and wetlands, particularly coastal forests such as mangroves. Mangroves are vital ecosystems that support local communities by providing fuelwood, construction material, medicine, food, fisheries, timber, and tannins [2, 3]. They also safeguard coastlines from flooding and store carbon [4,5,6]. However, climate-related risks, including sea-level rise, floods, and saltwater intrusion, threaten these ecosystems [7, 8]. Despite coping with seasonal and annual climate vulnerability, mangroves and their dependent communities remain vulnerable to climate change [7, 9, 10].

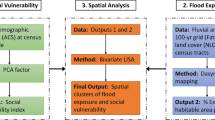

The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report indicates that the most significant potential for reducing near-term climate risk, especially in Africa, is reducing vulnerability [11]. The vulnerability assessment of communities to climate change offers information on the impact of changes on their livelihoods and the ability to cope at the household level and is a prerequisite for designing climate change adaptation strategies [12]. In the third IPCC assessment report, vulnerability was conceived as a function of exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity [13]. To better understand community vulnerability, various vulnerability assessment methodologies have been used, including participatory strategies, qualitative methodologies grounded in case studies, simulation models, indicator-centric approaches, and vulnerability mapping, as outlined by [14,15,16,17,18].

Various approaches have been employed to assess community vulnerability to climate change. For instance, community vulnerability to climate change has been assessed using a set of three key indicators, namely, exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity, as documented in previous studies [19, 20]. Additionally, both econometric and indicator-based methodologies have been applied. The econometric approach relies on socioeconomic survey data at the household level, whereas the indicator-based method systematically integrates natural, social, financial, physical, and human capital factors to gauge vulnerability levels [20,21,22,23,24].

The Tana Delta houses crucial natural resources, including mangrove forests, and was designated a Ramsar site in 2012. Whereas previous vulnerability assessments have been undertaken in other coastal areas in Eastern Africa, there is limited focus on the Tana Delta. Furthermore, in the Tana Delta, research has focused primarily on fisherfolk and fish-related aspects (e.g., [23, 25]), with limited attention given to other mangrove-dependent communities, such as farmers and pastoralists. This study addresses these gaps by integrating the sustainable livelihood framework (SLF) with the three dimensions outlined by the IPCC: exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity. Local knowledge was integrated to collect information on the unique vulnerabilities, adaptive capacities and needs of mangrove-dependent communities. Furthermore, this study expands on the SLF and IPCC dimensions by incorporating the concept of ecosystem services provided by mangroves to sustain livelihoods. In line with the indicator-based approach proposed by [26], this study evaluated 20 indicators. A participatory and systematic approach was employed to guide participants in assessing and prioritizing feasible actions to address identified challenges. The findings of this study are expected to inform decisions on sustainable livelihood issues. These findings can offer valuable insights for other coastal mangrove areas facing similar climate conditions and livelihood systems.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study area

The study was conducted on the Kenyan coast in the Tana Delta subcounty. It is within the larger Tana River County, between longitude 40.52°E and latitude 2.48°S. The sub-county has an area of approximately 16,012 km2. It shares borders with Lamu County to the east, Kilifi County to the southwest, the Tana River subcounty to the north and the Indian Ocean to the south. The Tana Delta, which is part of the Kenyan Coastal Plains, rises from sea level to 140 m [27]. It was designated a Ramsar site in 2012 and houses crucial natural resources [28]. Mangrove forests play a pivotal role in supporting the livelihoods of coastal communities [6]. Specifically, the Tana Delta sub-county includes the Kipini and Tarassa Division mangrove stands. For our study, we chose three sublocations (Ozi, Kipini, and Kilelengwani) (Fig. 1) due to their proximity to mangroves and similarities in their livelihoods and sociocultural aspects. We ensured a representative sample size at the 95% confidence level.

2.2 Desktop studies

2.2.1 Sampling techniques

The study used a proportional stratified random sampling technique where the number of households in each sublocation was determined by their number relative to the entire population. This ensured that each sublocation received proper representation within the sample [29]. In the first stage, this study adopted Cochran's sampling formula [30] to obtain a household sample size of 384:

*95% confidence level and p = 0.5 are assumedWhere n is the sample size; z is the selected critical value of the desired confidence level (z = 1.96); p is the estimated proportion of the attribute present in the population; q is 1-p (1–0.5 = 0.5); and e is the desired level of precision, set to + 5%; hence, e = 0.05. [30] suggested a correction formula to correct the sample size calculated by the infinite formula when the specific population size is known. Thus, the sample size in the equation above was corrected by Cochran's correction formula as follows:

Where n = the new sample size to be determined, n0 = the sample size derived from the equation above, and N = the actual sample size of the subjects (18,028). This yielded a sample size of 376. The following formula was used to determine the specific sample size in each sublocation:

Where n1 = the population of each sublocation (Kipini, Ozi, Kilelengwani) and N = the actual sample size (18,028). Thus, the sample sizes were—Kipini (235), Ozi (52) and Kilelengwani (76). In the second stage, lists collected from the chiefs assisted in randomly selecting households per sublocation. The local administration helped in the selection of participants for this study. This enabled the inclusion of different voices as per [31] recommendations.

2.2.2 Acquisition of satellite images for the past 30 years (1989 to 2019)

The satellite data used in the analysis were from Landsat 4–5 Thematic Mapper and Landsat 8 Operational Land Imager (OLI) imagery from the United States Global Survey (USGS) Landsat image archives covering the extent of the Kipini Division (Table 1). The data were collected for three periods: 1989, 1999, 2009, and 2020. Images were selected for the different months (February, May, and December) to reduce the effects of seasonality. The data were downloaded from https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/. Landsat images with less than 10% cloud cover were acquired, and some scenes from the same years were collected and computed to remove cloud cover.

2.2.3 Selection of indicators and criteria for their justification

Vulnerability is a function of exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity [1]. Indicators were chosen based on extensive literature reviews (Table 2). Historical climate variables (temperature and precipitation) were taken as exposure indicators. Sensitivity indicators were influenced by [32] and [33], who focused on the significance of employment and income for livelihoods [34]. Adaptive capacity indicators are aligned with the Department of International Development’s (DFID) sustainable livelihoods framework, where adaptive capacity hinges on livelihood assets, including physical, human, natural, financial, and social assets [35].

2.3 Fieldwork

In March 2019, reconnaissance visits to the study area involved local stakeholders, including government officials. Four community members and two experienced assistants were trained for data collection using household questionnaires, FGDs, and KIIs. The questionnaires were pretested with five households in Kipini, as recommended by [36]. Similarly, an FGD guide was tested for suitability, participatory processes, duration, and identification of emerging issues. Tools were translated into Kiswahili.

The data were collected from December 2019 to May 2020 and included participatory observations. Face-to-face interviews were conducted with a random sample of 377 households, preferably household heads or their spouses, using a questionnaire divided into four sections: demographic information (Section A), household livelihoods and income diversity (Section B), livelihood assets (Section C), and climate risks, responses, and impacts (Section D). This questionnaire provided data for identified vulnerability indicators (see Table 2).

Four focus group discussions (FGDs) involving 46 community members (24 men and 22 women) were conducted, with each FGD having no more than 12 participants, aligning with [37] recommendations. An experienced facilitator engaged with the discussants, seeking consent before the discussions. FGDs lasted 1 to 1.5 h, with information recorded through audio recording and notetaking. The topics covered included climate trends and risks, their impact on daily life and production, community livelihoods’ vulnerability to climate variability and climate risks and adaptation options.

A historical timeline was used to provide an overview of mangrove-dependent livelihood activities. A seasonal calendar was used to collect information on weather patterns and seasonal events affecting livelihood activities and provided valuable information when developing adaptation options. For key informant interviews (KIIs), 11 individuals representing the government, local organizations, leadership, and the community were selected based on stakeholder analysis. KIIs explored changes in mangrove extent, livelihoods, vulnerability factors and adaptation options.

Adaptation options were developed through community consultations and the use of vulnerability assessment results. The adaptation options were built upon discussions with communities on suitable adaptation options to mitigate negative projected impacts and a literature review of current adaptation options to determine best practices. Participants were provided with guidance throughout the process of evaluating all feasible actions aimed at addressing the identified challenges. This involved a systematic examination of various potential interventions, considering factors such as effectiveness, feasibility, and resource availability. Participants were encouraged to critically assess each option and weigh its potential impact against the local context through facilitated discussions and deliberations.

2.4 Data analysis

For mangrove cover change analysis, Landsat imagery data underwent several steps: conversion to radiance for better vegetation spectral properties, dataset correction, enhancement of the image’s appearance, and mangrove visibility. Images were classified into three groups: mangrove vegetation, non-mangrove vegetation (classified as bare land, developed land, and forests), and water bodies. The analysis relied on Landsat imagery band reflectance, revealing mangrove changes due to their distinct spectral properties.

Vegetation indices such as the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) and normalized difference water index (NDWI) were derived to improve classification. The combined mangrove recognition index (CMRI) was then calculated using a formula based on [38]:

ArcGIS version 10 was used to analyze the NDVI, NDWI and CMRI datasets and generate final output maps to monitor mangrove changes over time.

Data analysis commenced after the editing, coding, classification, and tabulation of the raw data. XLSTAT was utilized to analyze the data further. The demographic characteristics of the respondents, such as the number of household members, education, employment, and skills, were analyzed using percentages and frequencies. Frequencies and percentages were also generated for household livelihood and income options, livelihood assets and climate risks, responses, and impacts. The transcribed field notes and recordings from FGDs and KIIs were verified and coded in NVivo software under themes such as livelihoods, mangrove importance and dependence, changes in mangrove coverage, livelihood assets, and livelihood vulnerability. This enabled the researcher to identify similar views based on the themes presented in the study's findings and direct quotations where necessary.

To calculate the vulnerability index, the chosen indicators were normalized to bring their values within a close range, as recommended by [39]. Normalization was performed in Excel by subtracting the mean from the observed value and dividing it by the standard deviation for each indicator.

Principal component analysis (PCA) was run in XLSTAT for the normalized indicators to generate exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity indices. Finally, this study used the method employed by [40] in the computation of the vulnerability indices:

PCA helps extract key components among many variables to identify vulnerability determinants. The first set (component) was considered the most significant variation possible, and each subsequent set accounted for the possible remaining variability. The variables were converted into factors, and the coordinate of each variable was computed to ascertain the factor loadings. Factor loadings clarified how strongly the variables are associated with each factor discovered [41]. In addition, correlation analysis was used to determine the strength and direction of the relationships between several variables.

For the adaptation actions, once a comprehensive list of potential actions was generated, participants thoroughly examined various potential interventions, considering factors such as effectiveness, feasibility, and resource availability. Facilitated discussions and deliberations encouraged participants to critically assess each option.

3 Results

3.1 Mangroves and mangrove-based livelihood activities in the Tana Delta

The NDWI highlighted the water content of mangrove leaves, while the NDVI emphasized greenness. The NDWI and the NDVI output were compared to extract the mangrove vegetation. The first analysis revealed a strong correlation (− 0.988) and a robust inverse relationship. The analysis of the NDVI, NDWI, and CMRI datasets revealed accuracies between 81 and 94% from 1989 to 2020. The user’s accuracy ranged from 88 to 95%, and the kappa coefficient of the classification results was between 0.83 and 1, indicating perfect agreement between the extracted data and the mangrove layer. Due to their swampy environment and unique chlorophyll content, mangroves appear darker in multispectral images. The wet forest added distinguishing features.

The study revealed that the mangrove areas in the Kipini Division were 1425.2, 1345.6, 1366.7 and 1466.9 ha in 1989, 1999, 2009 and 2020, respectively. The mangrove area decreased by 79.6 ha (− 5.7%) from 1989 to 1999, increased by 21.1 ha (1.61%) from 1999 to 2009, and further increased by 100.8 ha (7.3%) between 2009 and 2020. The most significant cover loss occurred between 1989 and 1999. The results further suggest that most of the mangrove loss occurred seaward, while any recorded increases occurred landward. Loss of mangroves was also observed near Kipini (Fig. 2).

The study revealed that 63% of households depend on mangroves for their livelihoods. Among them, 52.1% primarily rely on mangroves for fishery products, mainly in the Ozi sublocation (over 90%). Additionally, 42.6% of the respondents used mangrove wood for firewood, 24.9% for building materials and 12.1% for making fishing implements. Other uses include medicine extraction medicine (11.3%), honey harvesting (6.4%), furniture making (3.0%), boat construction (1.9%), and tannin/dye production (0.8%). Regarding cooking fuel, 62.6% of households use firewood, 31.6% use a combination of charcoal and firewood, and a small fraction (2.9%) rely solely on charcoal. Only 2.9% of households use LPG or kerosene. An FGD participant confirmed the following:

“Mangroves are utilized for domestic and commercial purposes, with fish and honey being the most harvested products for domestic and commercial purposes. On the other hand, households gather poles and medicines mainly for domestic purposes.”

The proportion of community members who earn income from mangrove-based activities in each sublocation is 71% in Kipini, 57.8% in Kilelengwani and 28.9% in Ozi. Households were differentiated in terms of well-being by separating them based on their total income into high, medium and low income. The income source distribution revealed that 29 respondents (12.3%) had a high income of USD 1000/year, 75 respondents (31.9%) had a middle income between USD 500 and 1000/year, and 131 respondents (55.6%) had a low income of USD 500/year. The chi-square test confirmed that the relationships between mangrove forest income and different income levels were significant (P < 0.01). For this study, based on discussions during FGDs, an annual income of less than USD 500 was considered low, an income between USD 500 and USD 1000 was deemed medium, and an income of more than USD 1000 was considered high.

3.2 Vulnerability assessment

3.2.1 Vulnerability at the sublocation level

The mean vulnerability indices at the sublocation level ranged from 0.850 for Kipini to − 0.913 for Kilelengwani to − 2.702 for the Ozi sublocations (Fig. 3). Kipini falls within the moderately vulnerable category, while Kilelengwani and Ozi are highly vulnerable. The Kipini sublocation has the highest adaptive capacity, while the Ozi sublocation has the lowest.

3.2.2 Determinants of vulnerability

Significant determinants of vulnerability were identified from the ordered logistic regression model (Table 3). Although ten sensitivity indicators were hypothesized to be correlated with vulnerability, four indicators (household number, head of household’s age, dependents’ education, and dependents’ employment) had a significant influence (at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01) on vulnerability to climate change. The statistically significant (p < 0.05) adaptive capacity indicators in this study are ownership of assets, access to community infrastructure and services, condition/quality of houses, total income, and alternative sources of income. Exposure indicators, which include elevated temperatures and rainfall changes, are also significant (p < 0.01) in determining vulnerability.

3.2.3 Description of variables by vulnerability categories

Table 4 shows the results from an analysis of how much households in the three vulnerability classes differ in terms of the significant determinants of vulnerability. The less vulnerable households have more physical assets, are in good condition and have an average household monthly income above USD 500. They also have access to alternative income, primarily from non-nature-based sources such as businesses, as well as access to community infrastructure and services, including electricity. Similarly, for the sensitivity factors, they have a more significant percentage of heads of household between 30 and 40 years of age and have smaller household sizes (those with fewer than five members).

3.3 Exposure indicators of mangrove-dependent communities in the Tana Delta sub-county

Changes in rainfall and temperature were considered the main climate variables (Table 5). Regarding temperature increases, 68.1% of households from the household surveys in the Kipini Division perceived temperature increases over 30 years (1988 to 2018). Focus group discussions also confirmed the temperature increases and that these increases have become more persistent, especially over the last 30 years (1988 to 2018). The results from the household questionnaires indicate that just over half of the households (54.8%) interviewed in the Kipini Division perceived that there had been a change in rainfall (increase or decrease) in the 30 years preceding the interview (1988–2018). Of the respondents who perceived changes in rainfall, 90.9% were from the Ozi sublocation, while 67.5% and 44.1% were from the Kilelengwani and Kipini sublocations, respectively. Although respondents did not keep a detailed account of minor climatic variations, they identified periods when rainfall was above average and extended dry periods.

FGD participants reported an increase in the occurrence of hazards, such as floods and droughts, as well as longer-term incremental changes, including coastal erosion. The most widespread climate change impact reported was drought (84.1%), followed by floods (45.2%) (Fig. 4). The communities also perceived saltwater intrusion (35.8%), coastal erosion (23.9%) and sea-level rise (24.1%) as climate-related risks. The results of the study showed that farmers (85.8%), fisherfolk (85.5%) and petty traders (89.2%) all perceived drought as a significant climate-related risk.

3.4 Sensitivity indicators of mangrove-dependent communities in the Tana Delta sub-county

Table 6 shows the data on household size; the average household size is 6.3. It is worth noting that household size in this study does not necessarily refer to the size of the nuclear family but includes everyone living in the same house as the respondent, including relatives and grandchildren. Additionally, almost one-third of households (28.3%) had two or fewer children, 53.5% had three to six children, and 18.1% had more than six children.

Among the respondents, the majority (51.2%) were aged 31 to 50, with 14.8% in the 21 to 30 age group. This age distribution was consistent across all three sublocations: Kipini (52.2%), Ozi (48.9%), and Kilelengwani (49.4%). Additionally, 16.5% of respondents were above 60, with variations in different areas: Kipini (17.5%), Ozi (20%), and Kilelengwani (11.4%). FGDs confirmed that household heads were most active between the ages of 21 and 50.

Regarding education among dependents, 30.7% had attained at least a secondary school education. This distribution varied across sublocations, with higher percentages in Kipini (38.8%) than in Ozi (15.6%) and Kilelengwani (15.5%). Even those without formal education received basic Islamic education through madrassas. Additionally, a key informant mentioned government efforts to improve education quality enrollment in primary and secondary schools. Spouses and dependents faced high unemployment rates, at 98.1% and 93.0%, respectively.

3.5 Adaptive capacity indicators of mangrove-dependent communities in the Tana Delta sub-county

Household ownership of physical assets is generally low (Table 7). Regarding community infrastructure and services, most respondents (75.7%) lacked access to electricity, with only a minority (24.3%) having access. Regarding health facilities, 81.0% reported access to a public health center or dispensary, while 19.0% did not. FGDs highlighted the challenges these health facilities face, including shortages of medical personnel, equipment, and medications. A key informant shared:

"The limited access to basic services like health can add to the low adaptive capacity of the local communities."

The findings reveal that 75% of surveyed homes require renovation. They fall into distinct categories: 19.5% are temporary, 73.3% are semipermanent, and only 7.2% are permanent. Additionally, only 18.7% had cemented floors, 32.1% had corrugated iron sheet roofs, and 10.2% had walls made of bricks or stones. Notably, 89.8% of the respondents own their homes, while 10.2% do not. An FGD participant, however, noted:

“Addressing tenure rights and obtaining ownership documents for the land on which the houses are built is essential. Many homes are also constructed in high-risk areas”.

Field observations confirmed that certain villages, such as Bulla Mkoko, are at risk. A noticeable transition from mud walls and coconut-thatch roofs to stone/brick walls and corrugated iron roofs was also noted.

Table 8 shows the average annual household income. The FGDs confirmed that access to financial resources enhances the community's ability to ensure greater resilience to climate hazards such as drought and floods. The non-nature-based sources of income investigated in the study included ownership of a private business, rent, social security benefits, employment, family, savings, loans, and insurance (Fig. 5).

The proportion of community members participating in non-nature-based income-generating activities in each sublocation is 47.3% in Kipini, 28.9% in Kilelengwani and 2.2% in Ozi. An FGD participant said:

“I use the little cash I get to solve many problems, and I cannot save money. I want to diversify into other activities, including a small business. However, I am restricted because I cannot get enough money due to insufficient savings or access to credit or a loan”.

3.6 Relationships between vulnerability indicators and adaptive capacity

The results in Table 9 indicate that adaptive capacity positively correlates with head of household age (HOH AGE), although this correlation is not statistically significant. There were moderate positive correlations with “Education of Dependent” (ED DPDT) and “Employment of Dependent” (EMP DEPDT). Adaptive capacity has strong positive correlations with the number of assets (ASSET No.), total income (TOT INC), electricity availability (ELEC), loans (LOANS), business ownership (BUSINESS), and home conditions (HOME COND). There is a weak negative correlation between "frequency of high temperatures" (HIGH TEMP FREQ) and “head of household age” (HOH AGE), and this correlation is not statistically significant.

3.7 Proposed climate change adaptation options in Kipini division

Participants were guided to evaluate potential actions based on specific criteria, including urgency, significance, and local relevance. This approach helped prioritize measures that were most aligned with the community’s pressing needs and had the potential to have a meaningful impact. The climate change adaptation options were categorized into six response categories: (i) sustainable livelihoods; (ii) finance; (iii) technology, community infrastructure and services; (iv) formal and informal capacity and skills; (v) sustainable resource management; and (vi) governance and community planning. Sustainable livelihoods were identified as crucial for the adaptation of mangrove-dependent communities. In particular, the Matangeni FGDs advocated livelihood diversification. For cattle rearing, zero-grazing and dairy cattle were proposed. During the KIIs, Galla goats were recommended for their resilience, milk production, and rapid maturation. Poultry rearing was also recommended for the indigenous chickens. A focus group discussant confirmed that poultry rearing has picked up, and it can supplement diets and earn income. Beekeeping, though underutilized, was identified as promising, with training and support.

According to a key informant, fish farming is being encouraged, with plans for increased government support. FGDs in Ozi and Kilelengwani indicated that as Kipini Division, proposals for prawn (kamba) and crab (kaa) farming have been submitted in the past, with limited success, and proposed that these could be followed up. Furthermore, farming and selling live lobsters could earn a good income (up to USD 50 per kilogram) and could be explored as an adaptation option. FGDs reported that during the high season (January to February), lobster farmers could harvest between 200 and 300 kg per month. It was, however, expensive to start; support in the form of equipment and technical advice was needed.

Enhancing value through the development of crop, livestock, and fisheries value chains, in addition to bolstering cooperative structures, has emerged as a crucial strategy for accessing markets and stabilizing incomes. Fisherfolk supported the formation of cooperatives, and one of them confirmed that they sometimes spent several days at sea and eventually sold fish at low prices to brokers. Notably, a key informant further underscored the county’s endorsement of cooperatives, focusing on promoting cooperatives such as the Tana River Mango Marketing Cooperative. Eco-friendly initiatives such as plastic recycling and eco-tourism were proposed. Kipini FGDs noted that there had been previous attempts to set up an eco-tourism camp. KIIs were, however, cognizant that beach erosion has affected tourism enterprises in Kipini and proposed that setting up the enterprises should go hand in hand with environmental conservation activities.

FGDs, household surveys and vulnerability assessments highlight the importance of financial assets. Microfinance, including group savings and loans, boosts adaptive capacity. FGDs also noted the need to ensure the availability of funds to micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) for business growth. A key informant from the County Government agreed with this and noted that MSMEs play a vital role in economic development. Developmental partners have partnered with counties such as the Tana River to address financial barriers in local governance, which was acknowledged by FGDs as helpful in disentangling resource limitations. FGDs called for sustainable long-term investments in climate change interventions. KII cited the World Bank’s Program on Financing Locally Led Climate Action (FLLoCA), which aims to translate climate agendas into grassroots initiatives. FGDs recognized that different funding channels were available globally for climate change interventions. Key informants concurred and cited innovative funding mechanisms such as carbon-based funding, blended finance, and green bonds as examples. The participants further acknowledged that the climate finance landscape remains complex and needs to be demystified. Opening dialogs on innovative finance and private-sector investment were deemed crucial.

FGDs emphasized the importance of investing in modern agricultural technologies for adaptation but cited their inaccessibility and high costs as barriers. They also expressed the need for modern fishing equipment, noting that owning boats, engines and fishing gear would greatly benefit artisanal fisherfolk. Women in Matangeni advocated for clean energy technologies such as improved cookstoves (jikos) to reduce their reliance on forest resources. Moreover, FGD discussants in Kipini proposed promoting biomass briquettes as an alternative fuel source to lessen the dependence on mangrove trees. Additionally, a key informant suggested establishing tree nurseries and woodlots to provide alternative fuel sources.

Investment in climate-resilient infrastructure is pivotal in the adaptation efforts of the Kipini Division. A focus group discussant expressed the following:

“Good roads are key, and they connect different villages and towns even when it rains. We now have a good road from Witu to Malindi. However, we still use boats to move from Ozi to Kilelengwani. Even our mangoes must be transported by boat from Ozi. A good road from Ozi to Kilelengwani will ease our movement and open markets for mangoes and other goods”.

As the incidence of flooding increased, key informants stressed the urgency of addressing flooding incidents by exploring technologies such as groundwater recharge ponds. Climate information and early warning systems are recognized as key in providing timely responses to extreme weather events. FGDs have proposed incorporating disease risk predictions, updated data on the prices of essential commodities in key markets, and information about the geospatial distribution of available forage and water availability to enhance response mechanisms. To mitigate floods from upstream dams, FGDs recommended that the electricity generation company (KENGEN) establish a robust “early warning mechanism” to warn downstream communities before water is released.

Community services such as electricity, water supply, and healthcare need improvement. Discussants stressed the importance of undertaking studies to avoid drilling unproductive or saltwater boreholes. A key informant agreed with this and noted that the responsible government ministry was mapping the study area to identify where more boreholes could be drilled and where water pans could be constructed. Sustainable water management, including rainwater harvesting and reservoir construction, was cited as paramount. Additionally, a key informant noted that access to electricity, particularly in remote villages, is essential for sustainable livelihoods. FGDs, particularly in Ozi and Kilelengwani, proposed solar energy as an opportunity.

Formal and informal capacity and skills are integral for adaptive capacity. Women residing in Matangeni underscored the importance of enhancing educational standards and literacy levels within the Kipini Division. Additionally, a key informant perceived improving specific capacities and skills required for adaptation to climate change for local government technical officers, including extension officers, as crucial and noted:

"For the development and implementation of appropriate adaptation, there is a need for knowledge on current and future climate variability and economic valuation of the benefits of adaptation. Additionally, although climate change is reflected in our documents and plans as a cross-cutting issue, there is still a need to know how climate change can be integrated into subsectors."

This could include a capacity-building program at the county level to assist in developing bankable projects. A BMU member noted that formal community-based organizations (BMUs, CFAs and local CSOs) require capacity-building support for effective conservation efforts. This includes training forest guards in areas such as Kilelengwani and extension officers—NGOs are currently facilitating this training. Climate change awareness initiatives are crucial. A key informant opined that many impacts were still too far removed from daily activities; therefore, initiatives with an initial focus on local impacts would ensure engagement and inspire individual and community action.

The conservation and sustainable management of mangrove ecosystems are vital for coastal community adaptive capacity. Additionally, appropriate timing and monitoring of conservation efforts are necessary for success, with local organizations such as CFAs and BMUs playing a pivotal role in monitoring areas and reporting illegal activities. Integrated rangeland management and land use planning are proposed to address conservation-economic conflicts.

Improved governance and institutional frameworks emphasizing community engagement and collaboration are effective for climate change adaptation. The inclusion of women and bottom-up approaches is stressed for local ownership and sustainable outcomes. Strengthened collaboration between stakeholders and local communities is vital for codesigning and implementing adaptation interventions based on local knowledge and priorities.

4 Discussion

4.1 Mangroves and mangrove-based livelihoods

Between 1999 and 2020, the mangrove area in Kipini Division grew by 7.4%, expanding from 1345.6 hectares to 1444.9 hectares. This growth aligns with the findings of the Global Mangrove Watch (GMW) report, which indicated a 10.4% (578 hectares) increase in Kenya’s total mangrove area between 2016 and 2020, estimated at 54,430 hectares [42]. These findings support the reduced deforestation rates suggested by [43]; this can be attributed to efforts in mangrove conservation or natural regeneration processes. However, localized losses around Kipini indicate ongoing threats to mangrove habitats. Continuous conservation measures with a focus on ecological mangrove restoration are necessary. Notably, the significant mangrove loss in Southeast Asia [44] highlights the importance of considering local factors in mangrove conservation and restoration efforts.

In the Tana Delta, mangroves are vital for livelihoods, with 63.5% of households relying on mangroves. In addition to fisheries, mangroves also provide resources such as firewood and building materials. This reliance on mangroves for livelihoods is not unique to Kipini, as similar trends have been observed in other mangrove regions, such as the Sundarbans in Bangladesh [45]. Furthermore, the study findings indicate that the proportion of community members earning income from mangrove-based activities varies across sublocations, with greater dependence observed in Kipini than in Kilelengwani and Ozi. The findings also indicate that low-income households rely more on mangrove products than medium- and high-income households. These findings are consistent with research from other developing countries, such as Myanmar [46] and Bangladesh [45]. In establishing mangrove conservation and restoration initiatives, it is essential to consider ecosystem-based adaptation (EbA) approaches because they provide co-benefits for biodiversity, livelihoods, health, food security and carbon sequestration [1]. A particular focus on low-income households is also crucial.

4.2 Vulnerability assessment

Exposure: Coastal communities in the Tana Delta face multiple hazards, including increased temperatures, changes in rainfall patterns, droughts, floods, saltwater intrusion, coastal erosion, and rising sea levels. These environmental stressors worsen existing vulnerabilities and undermine socioeconomic stability. Targeted adaptation measures are needed to mitigate these risks, particularly in high-risk areas. Climate-resilient practices, training, resources, and technical assistance can help these communities adapt and sustain their livelihoods.

Sensitivity: The key sensitivity indicators in the study area include household size, the age of the head of the household, dependents’ education, and dependents’ employment. The average household size in Kipini was relatively large. The relationship between family size and vulnerability is multifaceted and context dependent. While large families may face challenges in resource allocation, as highlighted by [47], they may also possess adaptive capacities that enable them to cope with and respond to adversity.

Education levels among dependents were generally low, particularly in Ozi, indicating potential limitations in opportunities for adaptation. High unemployment rates among spouses and dependents further highlight mangrove-dependent communities' socioeconomic challenges, worsening their vulnerability to climate change impacts. Similar observations have been made among ethnic farmers in Vietnam and Ethiopia, underscoring the global importance of investing in human capital [48, 49]. The latest IPCC report also supports this, emphasizing the need for human capital investment for economic development and poverty reduction [11].

Adaptive capacity: The study revealed that average annual income levels varied among sublocations, with a considerable number of households earning less than USD 500 per year. Non-nature-based sources of income, such as private businesses and employment, were limited, particularly in Ozi, indicating challenges in diversifying livelihoods and reducing dependence on mangrove resources. The link between financial capacity or income and household vulnerability is consistent with observations in other regions worldwide, including southern Mozambique, Southeast Asia, and Bolivia [50,51,52].

Many houses require renovation, with notable deficiencies in housing quality. Moreover, the mention of tenure rights suggests that there may also be legal and socioeconomic challenges related to housing alongside physical inadequacies. Addressing this issue may include initiatives to improve housing conditions through renovation programs, strengthening land tenure security and community land titling initiatives.

The ownership of smaller household assets such as mobile phones and radios is widespread. These assets can be utilized to disseminate climate information and early warnings in remote areas, as supported by [53]. However, the ownership rates of physical assets such as tractors, irrigation systems, boat engines and fishing gear show significant disparities. Similar findings have been reported in studies conducted in Zanzibar [54] and Jamaica [55]. A lack of these physical assets hinders the efficiency and productivity of small-scale livelihood activities, leading to low returns, meager savings, and elevated poverty levels and, thus, increased vulnerability. Bridging this gap could involve asset-redistribution programs or exploring solutions such as skills development and training programs to maximize the effective use of existing resources.

At the community level, physical assets include infrastructure such as electricity and healthcare. However, approximately 25% of households have access to electricity, a situation common in developing countries, as observed by [56]. Inadequate healthcare provision, as well as deficient potable water, sewage, and drainage infrastructure, are prevalent issues in the lower Tana Delta. Comparable challenges have been highlighted in studies conducted in Kenya and Bangladesh's small coastal and riparian communities by [57] and [58], respectively. Remote indigenous communities in Australia also face infrastructure deficiencies and isolation, which exacerbate their vulnerability to climate change [59]. These findings underscore the global nature of these challenges, necessitating swift and cooperative action to ensure resilient infrastructure for all individuals, regardless of their location or socioeconomic status, in the face of climate change. Upgrading health facilities and enacting county-specific health laws are necessary for facilitating accessible and effective healthcare delivery.

Notably, the communities residing around the mangroves in the lower Tana Delta rely heavily on wood fuels such as charcoal and firewood for cooking. [60] observed that forest-adjacent communities favor firewood for cooking due to its availability and affordability. Given this context, the communities around mangroves will continue to depend on forest resources as an economical fuel source. However, the widespread use of wood fuels has detrimental environmental consequences and contributes to greenhouse gas emissions [61]. Clean energy technologies such as liquid petroleum gas (LPG) can substitute for mangroves as a fuel source. Nevertheless, the current cost of LPG at the study site ranges between 25 and 30 USD. Subsidies or financial assistance can support the adoption of clean energy technologies, especially among low-income households.

4.3 Relationship between vulnerability indicators and adaptive capacity

A weak negative correlation exists between adaptive capacity and household size, implying a slight decrease in adaptive capacity for larger households. Positive correlations are observed between adaptive capacity, the household head’s age, and the dependents' education level, suggesting increased capacity with older age and higher education. Research conducted in the Philippines has demonstrated that increased levels of education correlate with greater adaptive capacity [62]. Likewise, studies in Botswana have shown a positive correlation between age and adaptive capacity [63]. Moderate positive correlations with employment and asset ownership indicate greater adaptive capacity in households with more assets and jobs. This could be attributed to financial stability and access to resources that facilitate adaptation to changing circumstances [64]. Strong positive correlations with higher income, electricity access, loan availability, business ownership, and home conditions reflect economic stability and access to essential resources. There is a weak negative correlation with high temperatures and a very weak positive correlation with rain changes. This suggests that households in areas experiencing more frequent elevated temperatures may have slightly lower adaptive capacity.

Overall, this analysis highlights the multidimensional nature of adaptive capacity, which is influenced by socioeconomic factors, environmental conditions, and individual characteristics within households. This suggests that interventions to improve education, employment opportunities, asset ownership, income levels, access to essential services, and environmental resilience can enhance households' adaptive capacity and overall resilience.

4.4 Adaptation options

According to numerous studies, the availability of financial resources plays a vital role in building adaptive capacity [62, 65]. To address limited financial resources, interventions should prioritize income enhancement and the financial inclusion of mangrove-dependent communities. Facilitating access to microfinance provides savings options, credit facilities and other financial products that enable investment in alternative income-generating activities and build financial resilience. It plays a vital role in the absence of traditional banking services, which may be inaccessible or insufficient. Microfinance Institutions (MFIs) can also contribute to climate-smart lending practices by providing loans for climate-resilient agricultural practices and renewable energy technologies. Successful examples from countries such as Ethiopia demonstrate the effectiveness of group loans in enhancing income [66]. The lessons learned from the Building Resilience and Adaptation to Climate Extremes and Disasters (BRACED) program in Wajir, Kenya, also emphasize the importance of financial literacy programs and improved access to banking services in promoting saving and investment [67]. The full establishment of a microfinance corporation proposed by the Tana River County Microfinance Act (2017) is pivotal.

Innovative financial instruments such as green bonds can be considered in addition to traditional funding sources. Accelerating the development of the County Climate Finance Policy and aligning it with the National Finance Policy 2018 can enhance access to climate finance. Strengthening the capacity of relevant institutions in the county on innovative finance tools and mechanisms is essential. Long-term funds for transformative adaptation should also be allocated.

Diversifying livelihoods is crucial as a coping mechanism during hazards and a means for advancing livelihoods in favorable economic environments [64]. Typically, households with multiple income streams are less vulnerable and are better at recovering from climate change-induced shocks than those relying solely on a single income source. However, access to diverse income opportunities is limited in the lower Tana Delta. Findings from [54] in a coastal community in Zanzibar confirm these challenges faced by households in exploring alternative livelihood options. This is not easy for most households. According to [68], occupational identity and unfamiliarity with new activities pose challenges for social groups such as fishers. Additionally, households in deep poverty may lack the resources to diversify [69]. Therefore, training programs, financial support and well-informed initiatives are crucial for successful diversification. Microfinance initiatives and market linkages are particularly emphasized by [70]. Furthermore, cooperatives facilitate joint business ventures and benefit from economies of scale and support from other stakeholders. The county is committed to prioritizing cooperative policies and establishing funds.

Improving infrastructure and ensuring access to essential services are crucial for enhancing the adaptive capacity of mangrove-dependent communities. [71] and [11] agree on the significance of this aspect. Furthermore, prioritizing access to essential services, especially in vulnerable communities, is crucial for reducing disparities. Government policies should prioritize improving infrastructure in the Tana Delta, including housing, electricity, healthcare facilities, potable water, and sanitation systems. Investing in housing infrastructure can improve living conditions and enhance household resilience to environmental and socioeconomic shocks. This could include upgrading housing quality, implementing disaster-resistant construction standards, and providing subsidies or incentives for home improvements. Furthermore, given the long lifespan of built infrastructure, it is crucial to incorporate adaptation and resilience considerations for climate change impacts. Collaboration among government agencies, NGOs and stakeholders is necessary to address infrastructure gaps. Eco-friendly alternatives such as beach nourishment are recommended for coastal protection instead of sea walls. Additionally, regularizing land tenure rights and providing legal support for ownership documents can reduce vulnerability to displacement and land-related conflicts.

Continued investment in education and capacity-building programs is critical for enhancing the knowledge and skills needed to adapt to climate change. Strengthening technical skills for climate change adaptation and creating awareness at all levels is also crucial. Initiatives at the community level should include participatory approaches. Sustaining these efforts is essential, as highlighted by [72]. Local governments, such as the Tana County Government, should continue investing in the formal education sector and improving access to education for both males and females, particularly secondary schooling. [64] and [73] agree and emphasize the importance of robust institutions, which the county government is addressing to improve literacy levels.

Entrepreneurship skills training is also vital for formal sector employment and access to sustainable livelihoods. A vocational training center (VTC) is being established in Kipini to improve tertiary skills such as mechanics and electrical technology. County priorities include building the capacity of instructors, supplying learning and teaching materials, and providing bursaries to needy students. The German government plans to support VTCs in the coastal region through the “Go Blue” Initiative. Aligning vocational skills with local economic opportunities, as noted by [74], is essential, as is establishing a governance framework for VTC management. Connecting VTC trainees through business models and collaborating with county departments for employment can enhance effectiveness.

Promoting sustainable resource management practices in the Tana Delta region can enhance adaptive capacity. Investment in the restoration and conservation of mangroves can sustain communities’ reliance on them for various purposes, such as fishing, firewood, building materials and medicine extraction. Successful strategies from other regions include community-based mangrove restoration projects in Mozambique [75]. Furthermore, promoting clean and renewable energy alternatives such as liquid petroleum gas (LPG) can reduce the demand for wood fuel and contribute to the recovery of mangrove forests. Transitioning to sustainable energy sources requires implementing policies and incentives that address financial, economic, and regulatory barriers. [76] share a similar perspective and emphasize prioritizing clean and renewable energy alternatives.

Policy considerations such as participatory forest management (PFM) can foster local involvement and ownership in mangrove conservation and restoration efforts. Kenya’s Forest Act of 2007 initiated legislation for PFMs and highlighted the significant role community forest associations (CFAs) play in forest rehabilitation and management. The current Forest Conservation and Management Act of 2016 and the National Mangrove Ecosystem Management Plan, 2017–2027, also support collaborative forest management. However, [77] noted that the outcomes of PFM initiatives have varied across various locations. While mixed results have been observed in areas such as the Sundarbans in Bangladesh, positive outcomes have been observed in places such as Kwale in Kenya due to government support, donor assistance, and national partnerships.

Enforcement of policies and strengthening of institutions for sustainable resource management are needed at the local and national levels to ensure the preservation of resources and their ecological functions. Effective policy enforcement has contributed to the sustainable availability of mangrove resources in Southeast Asian countries, as demonstrated by [78]. However, addressing governance barriers, such as slow policy implementation and fragmented approaches, is crucial for successful adaptation, as highlighted by [79]. For instance, the Tana River County Climate Act 2021 was enacted on August 6. 2021 offers opportunities to establish frameworks for effective climate response. The Tana River County Integrated Development Plan can also facilitate coordinated adaptation efforts. Engaging in long-term planning that aligns with climate scenarios is also essential. Collaborative efforts involving the government, communities, and development partners are necessary. [11] stress the importance of expediting the implementation of adaptation programs across various dimensions, including knowledge generation, governance and finance. These dimensions align with the research findings, and addressing them promptly and effectively is crucial.

5 Conclusions

This study examines the importance of mangrove areas for communities' livelihoods and emphasizes the negative consequences of depleting these mangroves. This highlights the necessity of ongoing conservation and restoration efforts, considering regional disparities in mangrove loss. This study also revealed the vulnerabilities of mangrove-dependent communities in the Tana Delta. Factors such as limited education, financial resources, assets, infrastructure, and education contribute to the vulnerability of these communities.

A comprehensive and tailored strategy is necessary to address these vulnerabilities effectively. This strategy should include practical and holistic measures to achieve sustainable and meaningful results. Boosting financial resources should be a key focus, with microfinance institutions playing a crucial role by providing avenues for savings and credit and enabling investments in alternative income-generating activities. Establishing a microfinance corporation at the county level is essential to this goal. Diversifying livelihoods is imperative and is supported by training programs and financial assistance. Upgrading infrastructure upgrades, implementing early warning systems and ensuring access to essential services are pivotal in reducing exposure to extreme weather events. Collaboration among governmental bodies, NGOs, and stakeholders, along with formalizing land tenure rights, is essential for mitigating vulnerability. Investment in education, entrepreneurship skills, and sustainable resource management practices is also vital. Long-term planning aligned with climate scenarios and timely implementation.

Furthermore, policies focused on mangrove conservation and restoration, infrastructure development, access to services, education and human capital development are essential. Collaboration among various stakeholders is central to achieving inclusive outcomes and ensuring the success of these endeavors. While this study provides a foundation for future research in assessing vulnerabilities in similar settings, it is also important to note that its findings are context-specific and may change over time due to evolving indicators. Future studies should build upon the indicators used in this study and explore additional indicators to enhance understanding. It is also crucial to consider that adaptations that are beneficial to some people may increase the vulnerability of others or create long-term risks. Future research should address potential maladaptive outcomes and strive for sustainable solutions.

Data availability

The authors confirm that all the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

IPCC, et al. Summary for Policy Makers. In: Portner HO, Roberts DC, Tignor M, Poloczanska ES, Mintenbeck K, Alegria A, et al., editors. Climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability, contribution of WG II to the sixth assessment report of the IPCC. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2022.

Aheto DW, Kankam S, Okyere I, Mensah E, Osman A, Jonah FE, et al. Community-based mangrove forest management: Implications for local livelihoods and coastal resource conservation along the Volta estuary catchment area of Ghana. Ocean Coast Manag. 2016;127:43–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.OCECOAMAN.2016.04.006.

Hamza A, Esteves L, Cvitanovic M, Kairo J. Past and present utilization of mangrove resources in Eastern Africa and drivers of change. J Coast Res. 2020;95:39–44. https://doi.org/10.2112/SI95-008.1.

Macreadie PI, Anton A, Raven JA, Beaumont N, Connolly RM, Friess DA, et al. The future of blue carbon science. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11693-w.

Menéndez P, Losada IJ, Torres-Ortega S, Narayan S, Beck MW. The global flood protection benefits of mangroves. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61136-6.

Gitau P, Duvail S, Verschuren D. Evaluating the combined impacts of hydrological change, coastal dynamics and human activity on mangrove cover and health in the Tana River delta, Kenya. Reg Stud Mar Sci. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RSMA.2023.102898.

Ward R, Friess D, Day R, Mackenzie R. Impacts of climate change on mangrove ecosystems: a region-by-region overview. Ecosyst Health Sustain. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1002/EHS2.1211.

Nicholls RJ, Cazenave A. Sea-level rise and its impact on coastal zones. Science. 1979;2010(328):1517–20. https://doi.org/10.1126/SCIENCE.1185782.

Touza J, Lacambra C, Kiss A, Amboage RM, Sierra P, Solan M, et al. Coping and adaptation in response to environmental and climatic stressors in Caribbean coastal communities. Environ Manage. 2021;68:505–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00267-021-01500-Y/FIGURES/1.

Birkmann J, Liwenga E, Pandey R, Boyd E, Djalante R, Gemenne W, et al. Poverty, livelihoods and sustainable development. In: Portner H, Roberts D, Tignor M, Poloczanska K, Mintenbeck K, Alegria A, et al., editors. Climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of the WG II to the 6th assessment report of the IPCC. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2022. p. 1171–274. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844.010.

Trisos C, Adelekan IO, Totin E, Ayanlade A, Efitre J, Gemeda A, et al. Africa. In: Portner H, Roberts D, Tignor S, Poloczanska E, Mintenbeck K, Alegria A, et al., editors. Climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability contribution of the WG II to the sixth assessment report of the IPCC. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2022. p. 1285–455. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844.011.

Giri M, Bista G, Singh PK, Pandey R. Climate change vulnerability assessment of urban informal settlers in Nepal, a least developed country. J Clean Prod. 2021;307: 127213. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2021.127213.

IPCC. Climate change 2007: impacts adaptation and vulnerability. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007.

Vincent K. Creating an index of social vulnerability for Africa. Norwich: Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research Working; 2004.

Hahn M, Riederer A, Foster S. The Livelihood Vulnerability Index: a pragmatic approach to assessing risks from climate variability and change—a case study in Mozambique. Glob Environ Change Human Policy Dimens. 2009;19:74–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GLOENVCHA.2008.11.002.

Gerlitz JY, Macchi M, Brooks N, Pandey R, Banerjee S, Jha SK. The Multidimensional Livelihood Vulnerability Index—an instrument to measure livelihood vulnerability to change in the Hindu Kush Himalayas. Clim Dev. 2016;9:124–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2016.1145099.

Zhang Q, Zhao X, Tang H. Vulnerability of communities to climate change: application of the livelihood vulnerability index to an environmentally sensitive region of China. Clim Dev. 2018;11:525–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2018.1442808.

Gupta AK, Negi M, Nandy S, Kumar M, Singh V, Valente D, et al. Mapping socio-environmental vulnerability to climate change in different altitude zones in the Indian Himalayas. Ecol Indic. 2020;109: 105787. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECOLIND.2019.105787.

Liu Y, Zhao M, Liu D. Exposure, sensitivity, and social adaptive capacity related to climate change: empirical research in China. Chin J Popul Resour Environ. 2017;15:209–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10042857.2017.1365451.

Pandey R, Jha SK, Alatalo JM, Archie KM, Gupta AK. Sustainable livelihood framework-based indicators for assessing climate change vulnerability and adaptation for Himalayan communities. Ecol Indic. 2017;79:338–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECOLIND.2017.03.047.

Omerkhil N, Chand T, Valente D, Alatalo JM, Pandey R. Climate change vulnerability and adaptation strategies for smallholder farmers in Yangi Qala District, Takhar, Afghanistan. Ecol Indic. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECOLIND.2019.105863.

Jha C, Gupta V. Farmer’s perception and factors determining the adaptation decisions to cope with climate change: an evidence from rural India. Environ Sustain Indic. 2021;10: 100112. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.INDIC.2021.100112.

Huynh PTA, Le ND, Le STH, Nguyen HX. Vulnerability of fishery-based livelihoods to climate change in coastal communities in central Vietnam. Coast Manag. 2021;49:275–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2021.1899927.

Wu T. Quantifying coastal flood vulnerability for climate adaptation policy using principal component analysis. Ecol Indic. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECOLIND.2021.108006.

Dzoga M, Simatele D, Munga C. Assessment of ecological vulnerability to climate variability on coastal fishing communities: a study of Ungwana Bay and Lower Tana Estuary, Kenya. Ocean Coast Manag. 2018;163:437–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.OCECOAMAN.2018.07.015.

Sarker MNI, Cao Q, Wu M, Hossin AGM, Shouse RC. Vulnerability and livelihood resilience in the face of natural disaster: a critical conceptual review. Appl Ecol Environ Res. 2019. https://doi.org/10.15666/aeer/1706_1276912785.

Odhengo P, Matiku P, Nyangena J, Wahome K, Opaa B, Munguti S, et al. Tana River Delta Strategic Environmental Assessment. 2014.

GOK. National Mangrove ecosystem management plan 2017–2027. Kenya: Republic of Kenya; 2017.

Hennick M, Hutter I, Bailey A. Qualitative research methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2020.

Cochran W. Sampling techniques. 3rd ed. New York: Wiley; 1977.

Nyumba T, Wilson K, Derrick CJ, Mukherjee N. The use of focus group discussion methodology: insights from two decades of application in conservation. Methods Ecol Evol. 2018;9:20–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12860.

Islam M, Sallu S, Hubacek K, Paavola J. Vulnerability of fishery-based livelihoods to the impacts of climate variability and change: insights from coastal Bangladesh. Reg Environ Change. 2014;14:281–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10113-013-0487-6/TABLES/4.

Huynh LTM, Stringer LC. Multi-scale assessment of social vulnerability to climate change: an empirical study in coastal Vietnam. Clim Risk Manag. 2018;20:165–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CRM.2018.02.003.

Marshall N, Marshall P, Tamelander J, Obura D, Malleret-King D, Cinner J. A framework for social adaptation to climate change: sustaining tropical coastal communities and industries. Gland: IUCN-The International Union for the Conservation of Nature; 2009.

DFID. Sustainable livelihoods guidance sheets. London: DFID; 1999. p. 1999.

Ruel E, Wagner WE, Gillespie BJ. The practice of survey research: theory and applications. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2016. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483391700.

Dilshad R, Latif M. Focus group interview as a tool for qualitative research: an analysis. Pak J Soc Sci (PJSS). 2013;33:191–8.

Gupta K, Mukhopadhyay A, Giri S, Chanda A, Datta Majumdar S, Samanta S, et al. An index for discrimination of mangroves from non-mangroves using LANDSAT 8 OLI imagery. MethodsX. 2018;5:1129–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MEX.2018.09.011.

Nelson R, Kokic P, Crimp S, Meinke H, Howden SM. The vulnerability of Australian rural communities to climate variability and change: part I-conceptualising and measuring vulnerability. Environ Sci Policy. 2010;13:8–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENVSCI.2009.09.006.

Nellitz M, Boardley S, Smith S. Tools for climate change vulnerability assessments for watersheds: a report prepared for the Canadian Council of Ministers of Environment (CCME). 2013.

Meraj G, Romshoo SA, Ayoub S, Altaf S. Geoinformatics based approach for estimating the sediment yield of the mountainous watersheds in Kashmir Himalaya. India Geocarto Int. 2017;33:1114–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/10106049.2017.1333536.

Erftemeijer P, de Boer M, Hillarides L. Status of Mangroves in the Western Indian Ocean Region. 2022.

de Lacerda LD, Ferreira AC, Ward R, Borges R. Editorial: mangroves in the anthropocene: from local change to global challenge. Front For Glob Change. 2022;5: 993409. https://doi.org/10.3389/FFGC.2022.993409/BIBTEX.

Spalding M, Leal M. The State of the World Mangroves 2021. Global Mangrove Alliance; 2021.

Mallick B, Priodarshini R, Kimengsi JN, Biswas B, Hausmann AE, Islam S, et al. Livelihoods dependence on mangrove ecosystems: empirical evidence from the Sundarbans. Curr Res Environ Sustain. 2021;3: 100077. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CRSUST.2021.100077.

Aye W, Wen Y, Marin K, Thapa S, Tun A. Contribution of Mangrove forest to the livelihood of local communities in Ayeyarwaddy region, Myanmar. Forests. 2019;10:414. https://doi.org/10.3390/F10050414.

Nkondze M, Masuku M, Manyatsi A. Factors affecting households vulnerability to climate change in Swaziland: a case of Mpolonjeni area development programme (ADP). J Agric Sci. 2013. https://doi.org/10.5539/JAS.V5N10P108.

Sen S. Sunderban Mangroves, Post Amphan: an overview. Int J Creat Res Thoughts. 2020;8:2751–5.

Belay D, Fekadu G. Influence of social capital in adopting climate change adaptation strategies: empirical evidence from rural areas of Ambo district in Ethiopia. Clim Dev. 2021;13:857–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2020.1862741.

Zacarias DA. Understanding community vulnerability to climate change and variability at a coastal municipality in southern Mozambique. Int J Clim Chang Strateg Manag. 2019;11:154–76. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCCSM-07-2017-0145/FULL/PDF.

Bauer T, de Jong W, Ingram V, Arts B, Pacheco P. Thriving in turbulent times: livelihood resilience and vulnerability assessment of Bolivian Indigenous forest households. Land Use Policy. 2022;119: 106146. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.LANDUSEPOL.2022.106146.

Diana NIM, Zulkepli NA, Siwar C, Zainol MR. Farmers’ adaptation strategies to climate change in Southeast Asia: a systematic literature review. Sustainability. 2022;14:3639. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU14063639.

Donatti C, Harvey C, Hole D, Panfil S, Schurman H. Indicators to measure the climate change adaptation outcomes of ecosystem-based adaptation. Clim Change. 2020;158:413–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02565-9.

Makame M, Salum L, Kangalawe R. Livelihood assets and activities in two east coast communities of Zanzibar and implications for vulnerability to climate change and non-climate risks. J Sustain Dev. 2018. https://doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v11n6p205.

Baptiste A, Kinlocke R. We are not all the same!: Comparative climate change vulnerabilities among fishers in Old Harbour Bay. Jamaica Geoforum. 2016;73:47–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GEOFORUM.2015.05.006.

Twesigye P. Structural, governance, and regulatory incentives for improved utility performance: a comparative analysis of electric utilities in Tanzania, Kenya, and Uganda. Util Policy. 2022;79: 101419. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JUP.2022.101419.

Olago D, Marshall M, Wandiga SO, Opondo M, Yanda PZ, Kangalawe R, et al. Climatic, socio-economic, and health factors affecting human vulnerability to Cholera in the Lake Victoria Basin, East Africa. Ambio. 2007;36:350–8. https://doi.org/10.1579/0044-7447(2007)36.

Alam G, Alam K, Mushtaq S, Filho W. How do climate change and associated hazards impact on the resilience of riparian rural communities in Bangladesh? Policy implications for livelihood development. Environ Sci Policy. 2018;84:7–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENVSCI.2018.02.012.

Lansbury Hall N, Crosby L. Climate change impacts on health in remote indigenous communities in Australia. Int J Environ Health Res. 2020;32:487–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/09603123.2020.1777948.

Makonese T, Ifegbesan AP, Rampedi IT. Household cooking fuel use patterns and determinants across southern Africa: evidence from the demographic and health survey data. Energy Environ. 2017;29:29–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958305X17739475.

Elasu J, Ntayi JM, Adaramola MS, Buyinza F. Drivers of household transition to clean energy fuels: a systematic review of evidence. Renew Sustain Energy Transit. 2023;3: 100047. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RSET.2023.100047.

Defiesta G, Rapera C. Measuring adaptive capacity of farmers to climate change and variability: application of a composite index to an agricultural community in the Philippines. J Environ Sci Manag. 2014;17:48–62.

Cassidy L, Barnes GD. Understanding household connectivity and resilience in marginal rural communities through social network analysis in the village of Habu, Botswana. Ecol Soc. 2012. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-04963-170411.

Chepkoech W, Mungai NW, Stöber S, Lotze-Campen H. Understanding adaptive capacity of smallholder African indigenous vegetable farmers to climate change in Kenya. Clim Risk Manag. 2020;27: 100204. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CRM.2019.100204.

Lemos MC, Lo YJ, Nelson DR, Eakin H, Bedran-Martins AM. Linking development to climate adaptation: leveraging generic and specific capacities to reduce vulnerability to drought in NE Brazil. Glob Environ Chang. 2016;39:170–9.

Eshetu AA. Microfinance as a pathway out of poverty and viable strategy for livelihood diversification in Ethiopia. J Bus Manag Econ. 2014;5:142–51.

Ahmed M. Expanding access to financial services. In: Ahmed M, editor. Innovative humanitarian financing. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan; 2021. p. 135–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-83209-4_6.

Cinner J, Adger W, Allison E, Barnes M, Brown K, Cohen P, et al. Building adaptive capacity to climate change in tropical coastal communities. Nat Clim Chang. 2018;8:117–23. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-017-0065-x.

Cohen P, Lawless S, Dyer M, Morgan M, Saeni E, Teioli H, et al. Understanding adaptive capacity and capacity to innovate in social–ecological systems: applying a gender lens. Ambio. 2016;45:309–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/S13280-016-0831-4.

Djoudi H, Brockhaus M. Is adaptation to climate change gender neutral? Lessons from communities dependent on livestock and forests in northern Mali. Int For Rev. 2011;13:123–35. https://doi.org/10.1505/146554811797406606.

Sinay L, Carter RW. Climate change adaptation options for coastal communities and local governments. Climate. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/CLI8010007.

Omari-Motsumi K, Barnett M, Schalatek L. Broken connections and systemic barriers: overcoming the challenge of the “missing middle” in adaptation finance. 2019.

Aryal J, Rahut D, Marenya P. Climate risks, adaptation and vulnerability in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. In: Alam GM, Erdiaw-Kwasie MO, Nagy GJ, Leah Filho W, editors. Climate vulnerability and resilience in the global South. Cham: Climate Change Management, Springer; 2021. p. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77259-8_1/TABLES/4.

Kithae P, Awuor E, Letting N, Gesimba P. Impact of TVET institutions as drivers of innovative skills for sustainable development in Kenya. Kenya J Tech Vocat Educ. 2014;2:66–74.

Macamo C, Inácio da Costa F, Bandeira S, Adams JB, Balidy HJ. Mangrove community-based management in Eastern Africa: experiences from rural Mozambique. Front Mar Sci. 2024;11:1337678. https://doi.org/10.3389/FMARS.2024.1337678/BIBTEX.

Mungai EM, Ndiritu SW, Da Silva I. Unlocking climate finance potential and policy barriers—a case of renewable energy and energy efficiency in Sub-Saharan Africa. Resourc Environ Sustain. 2022;7: 100043. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RESENV.2021.100043.

Kairu A, Kotut K, Mbeche R, Kairo J. Participatory forestry improves mangrove forest management in Kenya. Int For Rev. 2021;23:41–54. https://doi.org/10.1505/146554821832140385.

Friess DA, Thompson BS, Brown B, Amir AA, Cameron C, Koldewey HJ, et al. Policy challenges and approaches for the conservation of mangrove forests in Southeast Asia. Conserv Biol. 2016;30:933–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/COBI.12784.

Owen G. What makes climate change adaptation effective? A systematic review of the literature. Glob Environ Chang. 2020;62: 102071. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GLOENVCHA.2020.102071.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge those whose contributions in various capacities have made this research possible. Special thanks to the community in the Tana Delta for their generous contributions

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Julie Mulonga and Prof Daniel Olago contributed to the study’s conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Julie Mulonga. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Julie Mulonga, and Prof Daniel Olago commented on earlier versions of the manuscript. Julie Mulonga and Prof Daniel Olago have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was assessed and approved as per the university guidelines and performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mulonga, J., Olago, D. Vulnerability to climate change of coastal mangrove-dependent communities in the Tana Delta, Kenya: a local perspective. Discov Environ 2, 68 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44274-024-00108-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44274-024-00108-3