Abstract

Purpose

Hospitalization of a child in PICU affects the psychological health and functioning of their family. In case of prolonged or repeated hospitalizations, sources of stress and family needs evolve, which leads to new challenges for families. To date, little is known about changes in the health of chronic critically ill (CCI) children’s family. We aimed to identify and compare psychosocial outcomes of mothers and fathers of CCI children overtime and the associated factors of better family functioning.

Methods

This national prospective longitudinal study was conducted in eight paediatric intensive care units in Switzerland. Outcome measures included perceived stress, PICU sources of stress, and family functioning using validated standard questionnaires. Family members with a CCI child completed self-reported questionnaires during PICU hospitalization, at discharge and 1 month later.

Results

A total of 199 mothers and fathers were included. Our results show high levels of stress experienced by parents throughout and after the hospitalization. Sources of stress are mainly related to child appearance and emotional responses and parental role alteration. Family functioning is low throughout the hospitalization and significantly decreased after 30 days of hospitalization (p = 0.002). Mothers experience higher physical and emotional family dysfunction than fathers after PICU discharge (p = 0.05). Family dysfunction is associated with pre-existing low child’s quality of life.

Conclusion

Our study highlights the importance of reducing the negative impact of PICU stay on parents’ psychosocial outcomes, through early emotional parental support, and appropriate response to their individual needs throughout and after PICU hospitalization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Parents experience multiple sources of stress during hospitalization of their child in paediatric intensive care unit (PICU), related to the child’s health condition, physical appearance, painful procedures, uncertainty of recovery, sights and sounds of the environment, and alteration of parental role [1,2,3]. The impact of PICU hospitalization can last for years after PICU discharge [4]. Prevalence rates of parental post-traumatic stress disorder range between 8 to 68% within 3 months post-discharge [5], in particular for parents of chronic critically ill (CCI) children [6]. Although there is no consensus definition for CCI children, they share common characteristics such as having a history of prolonged PICU stay and dependence on technology or persistent multiorgan dysfunction [6]. The experience of families is highly dependent on how staff respond to their needs [7]. The systematic review by Abela et al. revealed inconclusive evidence on gender differences in terms of psychological support needs [8]. Several studies published more than 10 years ago showed mothers, when compared to fathers, tend to have higher anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder [9,10,11], and others showed no gender differences [12, 13].

PICU hospitalization is disruptive for any family for the duration of the entire stay and beyond. In the context of paediatric chronic disease, higher family functioning has been positively associated with better child’s adjustment, social competence, and quality of life in both children and families [14,15,16]. However, this association has not been demonstrated in the PICU setting. A recent scoping review, including 21 PICUs, one mixed PICU/NICU, and one cardiac intensive care unit (CICU), revealed mixed results on the impact of a child’s PICU stay on general family functioning 6 months after PICU discharge. Despite inconsistent results, severity of illness and primary diagnostic appeared to be associated with poor family functioning, while lower baseline distress, greater social support, and being a two-parent family seemed to be protective factors of family functioning [17].

In this national prospective longitudinal study, we aimed to address the limited and inconclusive evidence of the impact of PICU stay on psychological health and family functioning in both mothers and fathers during and after PICU stay.

The primary objective of this cohort study was to determine the psychosocial health of family members of CCI children during PICU stay and 1 month later. Secondary objectives were to compare psychosocial outcomes between mothers and fathers over time, and to identify associated factors of better family functioning.

Methods

Study design and setting

This prospective longitudinal study was conducted in the eight PICUs in Switzerland, accounting for 100 beds and approximately 5000 annual admissions of medical and surgical paediatric patients, including neonates. Family visitation practice was similar across all participating units with no restrictions before March 2020 and restrictions to one family member at the bedside during the COVID pandemic.

Population

A non-probability convenient sample of family members of CCI children (see definition in Supplementary Table S1) was used. The estimation of the sample size was based on the number of children with a PICU LOS ≥ 8 days in the national database of the Swiss Society of Intensive Care Medicine and an estimated participation rate of 60%. Approximately we anticipated to enrol 200 family members in the study. Family members were eligible, if they were (a) the mother, the father, or a significant other, whether they were blood-related or not to the patient [18], and (b) fluent in French, German, or English. Family members were excluded if the child was in an end-of-life situation.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Swiss Human Research Ethics Committees related to the eight sites with the leading committee being the CER-VD, project-ID: 2019-00954. Written informed consent to participate in this study was obtained for each participating family member.

Data collection and study procedures

Clinical data were collected from the patient electronic record and psychological outcomes via self-reported questionnaires between November 2019 and February 2021, including a 3-month study suspension period (March–May 2020) due to COVID-19 health restrictions.

Data collection time points and measurements for each CCI group are described in Fig. 1. The number of measurements varied according to the PICU LOS.

Consenting family members completed the questionnaires, either online (via the secure web application REDCap) or in paper format using the pre-addressed postage-paid envelope for return. About 30 min was estimated for completion of all questionnaires. Three to five days after questionnaires distribution, a reminder was sent to participants using their email address or phone number. Simultaneously, each local investigator recorded the child’s clinical data in an electronic standardized care report form (eCRF) in REDCap.

Measurements

The children’s characteristics included the following: age, gender, planned hospitalization, type of CCI, number of technologies needed [19, 20], functional status [21], and medical diagnosis (Supplementary Table S2). Patients’ medical diagnosis were categorized as follows: cardiovascular, respiratory, neurological, digestive, oncology, sepsis, injury, and other diagnoses (prematurity, renal, digestive, hematologic, metabolic and others).

The family members’ characteristics included the following: relationship to the child, age, nationality, duration of residence in Switzerland, marital status, religious affiliation, education, current occupation, part-time/full-time work, number of siblings, yearly household income (in Swiss Francs), and perceived financial difficulties. Families’ organizational characteristics included commuting time between home and hospital, access to hospital accommodation, and time spent at the bedside per week.

Perceived child’s quality of life (QOL)

The PedsQL Generic Core Scale (four age-adapted versions, 21 to 55 items) assesses child’s health-related QOL and is completed by a parent [22]. The original and translated versions demonstrated good psychometric properties [22]. The item responses were assessed on a 5-point Likert scale. The total score ranges between 0 and 100, with higher scores indicating better perception of child’s QOL.

Perceived stress

The Perceived Stress Scale (10 items) demonstrated good psychometric proprieties [23, 24]. After a standardized process of translation and cultural adaptation to develop a German version [25], we performed reliability testing, showing good internal consistency (Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.82). Each item was assessed on a 5-point Likert scale (scores between 0 and 5). In addition, global scores of self-reported stress using a visual analogue scale (VAS, 100-mm horizontal line with verbal anchors to express the extremes of the severity of the symptom; scores of 0 = no stress and 100 = maximum stress) were used. The VAS was shown to provide perceived stress assessment similar to those obtained with former validated stress questionnaires [26], with good discriminant validity when comparing two groups [27].

PICU-related sources of stress

The Parental Stressor Scale: Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (37 items) demonstrated good psychometric properties [28]. The German and French versions were both translated and culturally adapted [25] and have good reliability for each domain (Cronbach alpha; French, range = 0.81–0.86; German, range = 0.72–0.87). Dimensions include sources of stress related to child’s appearance, behaviours and emotions, lights and sounds, procedures, professional staff, behaviour of professional staff, and parental role. Each item was assessed on a 5-point Likert scale; higher scores indicating higher stress (1 = not stressful to 5 = extremely stressful; with an option of “not experienced”).

Family functioning

The PedsQL™ Family Impact Module (36 items) measures parents’ perceptions of their own health-related QOL and the impact of child’s chronic health conditions on parental QOL and family functioning (87). Original and translated versions demonstrated good psychometric proprieties [29]. PedsQL™ has eight dimensions: physical, emotional, social, cognitive, communication, worry, daily activities, and family relationships and a total score. Each item score on a 5-point Likert scale was reversed and linearly transformed to a 0–100 scale (0 = 100, 1 = 75, 2 = 50, 3 = 25, and 4 = 0). The total scores range from 0 = poor family functioning to 100 = good family functioning.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to check for errors, missing data, and distribution and to describe sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of CCI children and family members. Categorical variables were summarized using frequency and percentage and continuous variables using mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range (IQR) if not normally distributed.

All data were categorized into 2 groups: mothers and fathers, except data from the only one participant who was neither a mother nor a father. Group comparisons were performed for nominal data with a Pearson’s chi-square test or a Fisher’s exact test and for continuous data with an independent t-test. Level of significance was two-sided α = 0.05. A mixed model for repeated measures was used to assess psychosocial changes over time, in which clustering controlled for more than one family member. Bivariate and multivariable linear regression mixed-models were conducted to identify associated factors with better family functioning at baseline, using family units and hospital unit as clusters. Model building investigated following variables:

Child-related factors are as follows: type of CCI patients (neonatal and paediatric CCI vs. frequently admitted), young age (≤ 2 years vs. > 2 years), diagnosis (cardiovascular, respiratory, neurological, digestive, other), child’s QOL, and functional status before PICU hospitalization (good, mild/moderate disability, severe disability) [30, 31].

Parents-related factors are as follows: relationship to the child, residence time in Switzerland married/in partnership, tertiary education, siblings, and perceived financial difficulties.

Significant variables at the level of 0.20 (conservatively) in the bivariate analysis were kept in the last multivariable logistic regression model [32]. Coefficient (b) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are used to report the results. Level of significance was two-sided α = 0.05. Analyses were performed using STATA version 15.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

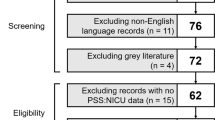

Data checking revealed < 10% of missing data, except for functional status (Pediatric Overall Performance Category (POPC) scores) with 30% of missing values (no specific pattern was found), and no problem of collinearity among variables (r > 0.4). Out of the 570 children that were screened, 174 CCI patients were included in analyses, the majority of whom were CCI children (66%), less than 2 years old (62%), and boys (56%). The CCI patients QOL was significantly lower 1 month post-PICU discharge when compared to pre-PICU admission (M = 78 and M = 70, p < 0.001, respectively) (Supplementary Table S3).

A total of 174 of families were included for analyses, of whom 99 families had one family member participating, and 75 families had two family members (see the flow chart in Supplementary Figure S1).

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the total sample and mothers (n = 136, 68%) and fathers (n = 63, 32%) separately. Most of the participants were Swiss (70%) or European (28%). The majority of them were married or in a partnership (82%), employed (71%), and had one or two children.

Compared to fathers, mothers were significantly less likely to be employed (94% vs 60%, p < 0.001) and when employed less likely to work more than 0.8 FTE (94% vs 60%, p < 0.001, respectively). Median number of hours per week spent at the bedside was 45 h, with no statistical difference between mothers (50, IQR 28–84) and fathers (38, IQR 20–70), p = 0.020.

Stress

The median parental level of stress on VAS scale significantly increased from before PICU admission (Mdn = 33, IQR 20–60) to baseline (Mdn = 70, IQR 49–80) and 1 month after PICU discharge (Mdn = 71, IQR 40–80) (b = 22.7 (95% CI = 17.3–28.1), p < 0.001). The mean perceived stress (PSS) at baseline was 2.9 (SD = 0.6) and significantly decreased 1 month after PICU discharge (b = 2.7, (SD = 0.7), p < 0.001). Table 2 presents the other parents’ psychosocial outcomes changes over time.

PICU-related sources of stress

Overall mean stress score was steady from admission (M = 2.6, SD = 0.7) to PICU discharge (M = 2.5, SD = 0.8) and 1 month after (M = 2.5, SD = 0.7). The highest sources of stress were parental role (mean between 3.2 and 3.3) and child’s appearance/behaviours/emotions (mean between 2.8 and 2.9). Related to this, lower score was observed at PICU discharge than during hospitalization (b = − 0.09 (95% CI = − 0.4–0.003), p = 0.05). Stress related to PICU procedures decreased significantly from baseline to discharge (b = − 0.27, p = 0.017) and 1 month after (b = − 0.30, p = 0.029).

Family functioning

Significantly lower score after 30 days of hospitalization were observed in the entire sample in physical (b = − 8.60, p = 0.002) and cognitive functioning (b = − 10.2, p = 0.003). Daily activities dimension had the lowest scores throughout the PICU hospitalization. It was significantly lower in those whose child was hospitalized ≥ 30 days. The daily activity score 1 month after PICU discharge was statistically higher than at admission (p < 0.05). Social functioning dimension was significantly lower 1 month after PICU discharge compared to baseline (b = − 4.37, p = 0.012).

Stress and family functioning differences between mothers and fathers at the different time points are presented in Supplementary Table S4.

The associated factors of better family functioning in CCI families are presented in Table 3. Based on the bivariate analysis results, the following variables were included in the multivariable analysis: child’s QOL and functional status before PICU admission, married/in-partnership, education, and perceived financial difficulties. The multivariable analysis shows a significant positive association between child’s QOL and family functioning (b = 0.34, p < 0.001) and a negative association between financial difficulties and family functioning (b = − 9.36, p = 0.037).

Discussion

This national study is the first to evaluate the psychosocial outcomes of CCI families over time and to compare these outcomes between mothers and fathers. This study confirms that mothers and fathers experience high level of stress throughout the PICU hospitalization and up to one month after PICU discharge, the main sources of stress being related to the child appearance and behaviours, and to the parental role alteration. Our findings reveal unmet informational and organizational needs and family dysfunction throughout the PICU hospitalization, especially when the child has lower QOL prior to the PICU hospitalization or when the family has financial difficulties.

Our study/results confirm(s) the results of the systematic review showing high level of stress during PICU stay among up to 80% of families of children with critical cardiac conditions [4]. In our study, perceived stress was significantly higher in mothers than fathers [2, 8, 33]. Emotional support interventions must respond to the “roller coaster” of emotions experienced by families throughout child’s hospitalization and beyond [1, 7, 34].

Our findings showed that the highest levels of stress were related to the child appearance behaviours and emotions and the parental role, as in other studies [2, 3, 35]. However, in different contexts, parental stress can be related to the sight and sounds in the PICU and to the procedures carried out on their child as well [36], which can be explained by the various healthcare systems characteristics and different patients’ chronic conditions. In our study, PICU environment and procedures done on children became less stressful for parents as they progressed throughout the PICU stay. This suggests adaptive strategies during PICU stay as well as familiarization with PICU environment and staff as described in two qualitative studies [37, 38]. In our study parental stress was associated with the child appearance and emotional responses and the parental role. Other studies corroborate our findings in which greatest stressor for parents was alteration to the parental role, followed by infant appearance [39] and where parents felt. However, most parents need to adapt with their child’s new environment and clinical conditions, including getting accustomed with equipment and technologies [7, 40]. It is, therefore, essential to identify the parents’ individual desires and needs to get involved, including whether they wish to be present at the bedside and participate in their child’s care [41]. Being intense advocates for their child, especially in situations of repeated PICU hospitalizations or pre-existing chronic conditions, makes the parental role more important [7]. The recognition of the parental expertise for their child, negotiation of partners’ boundaries, being really known by HCPs, and an inclusive decision-making process were found fundamental actions to decrease the parental role alteration in CCI families [41,42,43].

Our results show low family functioning among CCI families throughout and after the PICU hospitalization. This low family functioning can be explained by the altered parental role during hospitalization as well as the burden of the transition to chronic health conditions leading to social isolation [7, 38]. Other studies showed families of children with chronic conditions have lower score of family functioning than healthy controls [44,45,46]. In our study, families struggled to maintain daily activities, which is probably explained by the parental presence at the bedside and the return to work. However, most families, including those in our study, reported good relationships between family members [44,45,46]. Mothers of our sample showed worst physical, emotional, and cognitive functioning than fathers throughout PICU hospitalization. These results may be explained by the fact that mother spend more time at the bedside than fathers and by the higher level of stress in mothers than fathers [14, 15]. We recommend assessing the unmet needs and providing support to all family members and the family as a whole, as also suggested by Van Schoors et al. [15]. The integration of family nursing into routine care, including systemic family assessments and interventions, is an interesting avenue to support each family members by drawing on their strengths and mobilizing resources available within and outside of the family system [47]. In our study, poor family functioning was associated with low child’s QOL before PICU hospitalization. This finding is not surprising because families of children with a chronic condition experience high psychological distress in their daily life [4, 35] and low satisfaction with care in general [48].

This study has several strengths, including involvement of all the Swiss PICUs, and findings from different types of institutions. Longitudinal findings add valuable insights on the evolution of CCI families’ outcomes throughout and after PICU hospitalization. In addition, we were able to include a large number of fathers in our sample. Several limitations should be noted. First, as per our study objectives, we analysed the data of the three groups of CCI children together. Although our sample was constituted of CCI children with clear pre-defined inclusion criteria, it would be interesting to explore potential differences in family outcomes and needs within the three groups. This is addressed in secondary analyses of the data that will be published elsewhere. We excluded family members that were withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining medical treatment of the CCI child due to their different needs; yet, these families may have experienced higher stress and family dysfunction [7]. Finally, exclusion of families who did not speak or read French or German limited the cultural and ethnic diversity of PICU families in Switzerland.

Clinical implications

Our results show there is room for improvements. Patient and family-centred care (PFCC) with a family systemic perspective may be a pathway to enhance psychosocial outcomes and unmet needs of CCI families [18, 47]. We propose a synthesis of recommendations for the domains of nursing practice, management, education, and research in Fig. 2.

Conclusions

Our study underlines the importance of including mothers and fathers in caring of CCI children. Families report high negative emotional responses leading by numerous sources of stress, which affect their family functioning. Mothers may need more attention due to higher stress and lower emotional functioning than fathers. Providing support to CCI families early and throughout the PICU stay as well as after the PICU is recommended to enhance individualized care and minimize the negative effect of hospitalization.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

References

Hagstrom S (2017) Family stress in pediatric critical care. J Pediatr Nurs 32:32–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Pedn.2016.10.007

Alzawad Z, Marcus Lewis F, Ngo L, Thomas K (2021) Exploratory model of parental stress during children’s hospitalisation in a paediatric intensive care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 67:103109. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Iccn.2021.103109

Lisanti AJ, Allen LR, Kelly L, Medoff-Cooper B (2017) Maternal stress and anxiety in the pediatric cardiac intensive care unit. Am J Crit Care 26(2):118–125. https://doi.org/10.4037/Ajcc2017266

Woolf-King SE, Anger A, Arnold EA, Weiss SJ, Teitel D (2017) Mental health among parents of children with critical congenital heart defects: a systematic review. J Am Heart Assoc 6(2):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1161/Jaha.116.004862

Woolf C, Muscara F, Anderson VA, Mccarthy MC (2016) Early traumatic stress responses in parents following a serious illness in their child: a systematic review. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 23(1):53–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10880-015-9430-Y

Murphy Salem S, Graham RJ (2021) Chronic illness in pediatric critical care. Front Pediatr 9:686206. https://doi.org/10.3389/Fped.2021.686206

Grandjean C, Ullmann P, Marston M, Maitre MC, Perez MH, Ramelet AS (2021) Sources of stress, family functioning, and needs of families with a chronic critically ill child: a qualitative study. Front Pediatr 9:740598. https://doi.org/10.3389/Fped.2021.740598

Abela KM, Wardell D, Rozmus C, Lobiondo-Wood G (2020) Impact of pediatric critical illness and injury on families: an updated systematic review. J Pediatr Nurs 51:21–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Pedn.2019.10.013

Bronner MB, Kayser AM, Knoester H, Bos AP, Last BF, Grootenhuis MA (2009) A pilot study on peritraumatic dissociation and coping styles as risk factors for posttraumatic stress, anxiety and depression in parents after their child’s unexpected admission to a pediatric intensive care unit. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 3(1):33. https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-3-33

Bronner MB, Knoester H, Bos AP, Last BF, Grootenhuis MA (2008) Follow-up after paediatric intensive care treatment: parental posttraumatic stress. Acta Paediatr 97(2):181–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1651-2227.2007.00600.X

Bronner MB, Peek N, Knoester H, Bos AP, Last BF, Grootenhuis MA (2010) Course and predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder in parents after pediatric intensive care treatment of their child. J Pediatr Psychol 35(9):966–974. https://doi.org/10.1093/Jpepsy/Jsq004

Ehrlich TR, Von Rosenstiel IA, Grootenhuis MA, Gerrits AI, Bos AP (2005) Long-term psychological distress in parents of child survivors of severe meningococcal disease. Pediatr Rehabil 8(3):220–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/13638490400022246

Stremler R, Haddad S, Pullenayegum E, Parshuram C (2017) Psychological outcomes in parents of critically ill hospitalized children. J Pediatr Nurs 34:36–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Pedn.2017.01.012

Leeman J, Crandell JL, Lee A, Bai J, Sandelowski M, Knafl K (2016) Family functioning and the well-being of children with chronic conditions: a meta-analysis. Res Nurs Health 39(4):229–243. https://doi.org/10.1002/Nur.21725

Van Schoors M, Caes L, Knoble NB, Goubert L, Verhofstadt LL, Alderfer MA (2017) Systematic review: associations between family functioning and child adjustment after pediatric cancer diagnosis: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Psychol 42(1):6–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/Jpepsy/Jsw070

Mendes TP, Crespo CA, Austin JK (2017) Family cohesion, stigma, and quality of life in dyads of children with epilepsy and their parents. J Pediatr Psychol 42(6):689–699. https://doi.org/10.1093/Jpepsy/Jsw105

O’Meara A, Akande M, Yagiela L, Hummel K, Whyte-Nesfield M, Michelson KN, Et Al (2021) Family outcomes after the pediatric intensive care unit: a scoping review. J Intensive Care Med 8850666211056603. https://doi.org/10.1177/08850666211056603

Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC, Puntillo KA, Kross EK, Hart J et al (2017) Guidelines for family-centered care in the neonatal, pediatric, and adult ICU. Crit Care Med 45(1):103–128. https://doi.org/10.1097/Ccm.0000000000002169

Marcus KL, Henderson CM, Boss RD (2016) Chronic critical illness in infants and children: a speculative synthesis on adapting ICU care to meet the needs of long-stay patients. Pediatr Crit Care Med 17(8):743–752. https://doi.org/10.1097/Pcc.0000000000000792

Srivastava R, Stone BL, Murphy NA (2005) Hospitalist care of the medically complex child. Pediatr Clin North Am 52(4):1165–1187. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Pcl.2005.03.007

Fiser DH (1992) Assessing the outcome of pediatric intensive care. J Pediatr 121(1):68–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3476(05)82544-2

Varni JW, Seid M, Rode CA (1999) The Pedsql: measurement model for the pediatric quality of life inventory. Med Care 37(2):126–139

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R (1983) A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 24(4):385–396

Langevin V, Boini S, François M, Riou A (2015) Risques psychosociaux: Outils D’évaluation. Références En Santé Au Travail 143:101–104

Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, Eremenco S, Mcelroy S, Verjee-Lorenz A et al (2005) Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: report of the ISPOR task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value Health 8(2):94–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1524-4733.2005.04054.X

Barré R, Brunel G, Barthet P, Laurencin-Dalicieux S (2018) Perceived stress assessment using a visual analogue scale: validation and implication in the periodontal risk analysis. J Clin Periodontol 45:14–14

Lesage FX, Berjot S, Deschamps F (2012) Clinical stress assessment using a visual analogue scale. Occup Med 62(8):600–605. https://doi.org/10.1093/Occmed/Kqs140

Carter MC, Miles MS (1989) The parental stressor scale: pediatric intensive care unit. Matern Child Nurs J 18(3):187–198

Varni JW, Sherman SA, Burwinkle TM, Dickinson PE, Dixon P (2004) The Pedsql family impact module: preliminary reliability and validity. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2:55. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-2-55

Pollack MM, Holubkov R, Reeder R, Dean JM, Meert KL, Berg RA et al (2018) PICU length of stay: factors associated with bed utilization and development of a benchmarking model. Pediatr Crit Care Med 19(3):196–203. https://doi.org/10.1097/Pcc.0000000000001425

Pagowska-Klimek I, Pychynska-Pokorska M, Krajewski W, Moll JJ (2011) Predictors of long intensive care unit stay following cardiac surgery in children. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 40(1):179–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Ejcts.2010.11.038

El Sanharawi M, Naudet F (2013) Understanding logistic regression. J Fr Ophtalmol 36(8):710–715

Bedford ZC, Bench S (2019) A review of interventions supporting parent’s psychological well-being after a child’s intensive care unit discharge. Nurs Crit Care 24(3):153–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/Nicc.12405

Alzawad Z, Lewis FM, Kantrowitz-Gordon I, Howells AJ (2020) A qualitative study of parents’ experiences in the pediatric intensive care unit: riding a roller coaster. J Pediatr Nurs 51:8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Pedn.2019.11.015

Ramirez M, Navarro S, Claveria C, Molina Y, Cox A (2018) Parental stressors in a pediatric intensive care unit. Rev Chil Pediatr 89(2):182–189. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0370-41062018000200182

Aamir M, Mittal K, Kaushik JS, Kashyap H, Kaur G (2014) Predictors Of stress among parents in pediatric intensive care unit: a prospective observational study. Indian J Pediatr 81(11):1167–1170. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12098-014-1415-6

Bogetz JF, Trowbridge A, Lewis H, Shipman KJ, Jonas D, Hauer J et al (2021) Parents are the experts: a qualitative study of the experiences of parents of children with severe neurological impairment during decision-making. J Pain Symptom Manage 62(6):1117–1125. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Jpainsymman.2021.06.011

Geoghegan S, Oulton K, Bull C, Brierley J, Peters M, Wray J (2016) The experience of long-stay parents in the ICU: a qualitative study of parent and staff perspectives. Pediatr Crit Care Med 17(11):E496–E501. https://doi.org/10.1097/Pcc.0000000000000949

Govindaswamy P, Laing S, Waters D, Walker K, Spence K, Badawi N (2019) Needs and stressors of parents of term and near-term infants in the NICU: a systematic review with best practice guidelines. Early Hum Dev 139:104839. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Earlhumdev.2019.104839

Foster K, Young A, Mitchell R, Van C, Curtis K (2017) Experiences and needs of parents of critically injured children during the acute hospital phase: a qualitative investigation. Injury 48(1):114–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Injury.2016.09.034

Rennick JE, St-Sauveur I, Knox AM, Ruddy M (2019) Exploring the experiences of parent caregivers of children with chronic medical complexity during pediatric intensive care unit hospitalization: an interpretive descriptive study. BMC Pediatr 19(1):272. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12887-019-1634-0

Wool J, Irving SY, Meghani SH, Ulrich CM (2021) Parental decision-making in the pediatric intensive care unit: an integrative review. J Fam Nur 27(2):154–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074840720975869

Koch A, Albrecht T, Kozhumam AS, Son H, Brandon D, Docherty SL (2021) Crossroads of parental decision making: intersections of hope, communication, relationships, and emotions. J Child Health Care 13674935211059041. https://doi.org/10.1177/13674935211059041

De Kloet AJ, Lambregts SA, Berger MA, Van Markus F, Wolterbeek R, Vliet Vlieland TP (2015) Family impact of acquired brain injury in children and youth. J Dev Behav Pediatr 36(5):342–351. https://doi.org/10.1097/Dbp.0000000000000169

Mishra K, Ramachandran S, Firdaus S, Rath B (2015) The impact of pediatric nephrotic syndrome on parents’ health-related quality of life and family functioning: an assessment made by the Pedsql 4.0 family impact module. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 26(2):285–292

Kountz-Edwards S, Aoki C, Gannon C, Gomez R, Cordova M, Packman W (2017) The family impact of caring for a child with juvenile dermatomyositis. Chronic Illn 13(4):262–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742395317690034

International Family Nursing Association (2017) IFNA position statement on advanced practice competencies for family nursing. https://internationalfamilynursing.org/2017/05/19/Advanced-Practice-Competencies/. Accessed 15 June 2021

Lessa AD, Cabral FC, Tonial CT, Costa CAD, Andrades GRH, Crestani F et al (2021) Brazilian translation, cross-cultural adaptation, validity, and reliability of the empowerment of parents in the intensive care 30 (EMPATHIC-30) questionnaire to measure parental satisfaction in PICUs. Pediatr Crit Care Med 22(6):e339–e348. https://doi.org/10.1097/pcc.0000000000002594

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all parents who consented to participate in the study. A warm thank to Dr. Pierluigi Ballabeni (Institute of Higher Education and Research in Healthcare (IUFRS) for the statistical analysis support and to all members of the OCToPuS Consortium. The authors also wish to express their special thanks to the study nurses for their strong commitment in family recruitment.

OCTOPUS Study group members:

Pediatric intensive care unit, Department Woman-Mother-Child, Lausanne University Hospital, Lausanne, Switzerland (Anne-Laure Lauria); Pediatric and neonatal intensive care unit, Department of Pediatrics, Gynecology and Obstetrics, University Hospitals of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland (Angelo Polito; Nathalie Bochaton); Pediatric intensive care and pulmonology, University Children’s Hospital Basel UKBB, Basel, Switzerland (Daniel Trachsel; Mark Marston); Pediatric intensive care unit, Department of Children and Adolescents, University Hospital, Bern, Switzerland (Silvia Schnidrig, Tilman Humpl); Pediatric and neonatal intensive care unit, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Switzerland, St. Gallen, Switzerland (Bjarte Rogdo; Ellen Wild); Pediatric and neonatal intensive care unit, Department Children’s Hospital, Lucerne Cantonal Hospital, Switzerland (Thomas Neuhaus; Sandra Stalder); Department of neonatal and pediatric intensive care, University Children‘s Hospital, Zurich, Switzerland (Barbara Brotschi; Franziska von Arx; Anna-Barbara Schlüer); Pediatric and neonatal intensive care unit, Department of Pediatrics, Cantonal Hospital Graubuenden, Chur, Switzerland (Thomas Riedel, Pascale Van Kleef).

Take-home message

In parents of children with a chronic critical illness, stress level was elevated and remained unchanged throughout PICU stay and 1 month after discharge. Family functioning was significantly altered throughout and was negatively associated with pre-existing low child’s QOL. CCI families require specific support to decrease the negative impact of PICU hospitalization on their psychosocial health.

Tweet

Families with a chronic critically ill child need support to decrease stress and improve family functioning during and after a PICU stay.

Funding

This study was funded by the Marisa Sophie Foundation Switzerland, the Anna & André Livio Glauser Foundation Switzerland, the Stiftung Pflegewissenschaft Schweiz, and an ESPNIC-Gettinge research grant for the coordination and the data collection in each site.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

CG, ASR, and MCM contributed substantially to conception and design of the study. CG and members of the OCToPuS study group contributed substantially to the data collection. CG and ZR performed the data analyses that were overseen by ASR. CG, ZR, ASR, and MHP interpreted the data. CG wrote the first draft of the manuscript. ZR and ASR substantially reviewed sections of the manuscript. All authors provided critical revision of the article and approved the version submitted for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Swiss Human Research Ethics Committees related to the eight sites with the leading committee being the CER-VD, project-ID: 2019-00954. Written informed consent to participate in this study was obtained for each participating family member.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table S1.

Pre-defined criteria of Chronic Critically Ill (CCI) children. Supplementary Table S2. Definition of variables. Table S3. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of CCI patients. Supplementary Figure S1. Flow chart.

Additional file 2: Supplementary Table S4.

Psychosocial outcomes of family members: differences between mothers and fathers.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grandjean, C., Rahmaty, Z., Perez, MH. et al. Psychosocial outcomes in mothers and fathers of chronic critically ill children: a national prospective longitudinal study. Intensive Care Med. Paediatr. Neonatal 2, 9 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44253-024-00027-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44253-024-00027-4