Abstract

Background

Patient extended length of stay has been scarcely studied in Australian inpatient psychiatric units (IPUs). Previous research has focused on public IPUs, however, private IPUs also care for a large proportion of people with mental illness.

Objectives

This study aimed to identify patient, clinical, and treatment characteristics associated with ELOS within a private IPU and compare these characteristics with those of public IPUs. It is hypothesised that patients with ELOS will have complex characteristics such as high unemployment status, multiple psychiatric diagnoses and physical health comorbidities.

Method

This cross-sectional study examined characteristics of ELOS in a private Australian IPU between 1st July 2018 and 30th July 2019. A retrospective patient file audit collected characteristics of ELOS patients.

Results

Of the 54 ELOS patients (M = 42.52 years [18.62]) admitted, the average LOS was 55.04 days (SD = 4.4 days). Most patients were female (77.8%), single (44.4%) and their income status was unemployed (25.9%), employed (24.1%) and pensioner (22.2%). The most prevalent psychiatric diagnoses were major depressive disorder (29.6%), eating disorder (24.1%), alcohol or substance use disorder (7.4%), and complex post-traumatic stress disorder (7.4%) respectively.

Conclusion

This study highlights patient, clinical, and treatment characteristics prevalent among private inpatients with ELOS. Future research should examine whether these are distinct from admissions that are not prolonged, with the aim to identify and reduce ELOS, and improve patient recovery, hospital flow and capacity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Length of stay (LOS) is an important measure in psychiatric hospital settings and is a nationally agreed key performance indicator for both public and private admissions to psychiatric inpatient units [1]. Extended length of stay can have negative impacts on both patients and health services. An extended inpatient stay may result in private insurance providers refusing to cover the cost of readmission to hospital in the days following discharge, leaving private patients with a lack of access to inpatient or a significant out of pocket cost for psychiatric treatment care [2]. It is also essential for private hospital administrators to consider the financial implications of ELOS, especially when measuring the overall cost of hospitalisation in private settings as health funds may offer reduced payments for extended psychiatric admissions. This can affect the long-term viability of private health services.

When examining the clinical factors associated with ELOS, research comparing the public and private psychiatric sector has found contradicting evidence. In private psychiatric hospitals, overactive or aggressive behaviour, drinking problems and hallucinations or delusions are associated with shorter LOS, whereas depressed mood, difficulties with activities of daily living [3] and complex diagnostic [4] are associated with longer stays. These factors are different from the public sector where involuntary admissions, more severe symptoms on admission, unemployment, limited social connections and a primary diagnosis of psychotic disorders are found to be associated with ELOS [5]. Furthermore, recorded diagnoses among public and private psychiatric inpatients varies significantly. The proportion of ELOS patients with schizophrenia or psychotic illness is considerably higher in an Australian public setting at 69% [5] compared to only 9.1% [6] in a private setting. In contrast, rates of affective disorders are two times higher in a private Australian inpatient unit (47%) compared to public one (24.3%). Similarly, substance use disorders were almost two times greater in a private setting (16.4%) compared to a public inpatient unit (9.3%).

Furthermore, a Cochrane review observed that short-stay hospitalization in public patients with schizophrenia was associated with improved patient outcomes in terms of social functioning, reintegration into society, finding employment and less reliance on institutional care [7]. The researchers also concluded that shorter LOS does not cause higher rates of loss to follow-up in community services or likelihood of readmittance, hence not contributing to increased ‘revolving door patients’ [7]. Admissions should be aimed at maximum input in first few weeks with timely discharge and follow-up with outpatient community involvement to improve re-integration and functioning in society [8].

The Australian private sector provides a significant proportion of mental health beds [9] but there is a scarcity of research examining the characteristics of ELOS patients admitted to private psychiatric inpatient units (IPUs) as compared with those of public IPUs. This study sought to demonstrate the patient, clinical, and treatment characteristics of people admitted to a private psychiatric IPU.

2 Methods

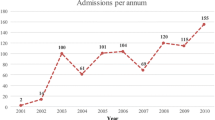

The study was conducted at a private psychiatric hospital in Melbourne, Australia. A retrospective file audit included all patient admissions between 1st July 2018 and 30th July 2019where LOS was 2 standard deviations or greater than average LOS (Fig. 1). All case data were deidentified. The database for this study cannot be publicly shared due to patient confidentiality. A de-identified version of the database may be provided upon request.

The aim was to identify the patient, clinical, and treatment characteristics associated with extended psychiatric patient stays; and compare these characteristics with those of public psychiatric settings. All data points are listed in Table 1 below. Data was collected by authors LJ, GR and medical staff AV and PH. The study was approved by The Melbourne Clinic Human Research Ethics Committee (TMC HREC #341) and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and TMC HREC. As the study was a retrospective file audit of hospital data and did not require the direct involvement of research participants, the need for informed consent was waived by TMC HREC. The STROBE guidelines [9] were utilized in the reporting of this cross-sectional study.

2.1 Data analysis

Descriptive statistical analysis of data was performed on the demographic, clinical and treatment characteristics collected. This data was analysed using SPSS version 21, for frequency, mean and distribution, prevalence rates, and a Pearson’s chi-squared test was used to determine statistical significance. For non-normative distributed data, non-parametric equivalent tests were used.

3 Results

3.1 Demographic factors

There were 2969 patients discharged from The Melbourne Clinic between 01/07/2018 and 30/06/2019 (M = 18.03, SD = 15.23, Range 1–112 days). ELOS patients were characterised as having an average admission length as 2SD greater than average 55 days (range 49–63 days). Of the 54 ELOS patients, the mean age was 42.54 years (range of 20–87 years) and most patients were female (77.8%, 42/54). Almost half were single (44.4%, 24/54) and a quarter married (25.9%, 14/54). Employment status was equally spread between employed (24.1%, 13/54), unemployed (25.9%, 14/54), pensioner (22.2%, 12/54). Most patients were private health insurance funded (88.9%), with a small minority being self-funded (3.7%, 2/54) and TAC funded (3.7%, 2/54). Preadmission living arrangements were spread among living with family (35.5%, 19/54), with partner (24.2%, 13/54), alone (20.5%, 11/54) and with friends (7.5%, 4/54). Most patients resided in advantaged Local Government Areas or suburbs (71.1% [38/54] from quintile 4 and 5, being the two highest ranked socio-economic categories in Australia [10]. A summary of sociodemographic characteristics found in ELOS patients is provided in Table 2.

3.2 Clinical factors

Patients admitted to The Melbourne Clinic with ELOS various diagnoses including major depressive disorder (29.6%, 16/54), eating disorder (24.1%, 13/54), a psychotic disorder (11.1%, 6/54) and alcohol or substance use disorders (7.4%, 4/54). Generalised anxiety disorder was present in 3.7% (2/54) of patients and 5.6% (5/54) had borderline personality disorder. The mean number of comorbid psychiatric diagnoses was 2 and the mean Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS) score was 18/48 (range 0–32). Physical health conditions were highly prevalent with 91% (41/54) of patients having at least one comorbid medical diagnosis. A complete list of psychiatric diagnoses and patient risk history is listed in Table 3.

3.3 Treatment factors

Most patients took between two and four psychotropic medications on admission (69.7%, 38/54) with 18.5% (10/54) taking one, 27.8% (15/54) taking two and 22.2% (12/54) taking three regular medications, and only 3.7% (2/54) of patients taking no regular medications. Fifty percent (27/54) took no pro re nata (PRN) medications and 40% (22/54) took at least one PRN medication. Inpatient electroconvulsive therapy accounted for 9.3% (5/54) of admissions.

Most patients were admitted to a general program (59.3%, 32/54) and the mean number of prior admissions to TMC is 5.5 (range 0–58). Readmission to a specialist programs (Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing [EMDR], obsessive compulsive disorder [OCD] and eating disorder programs) accounted for 22.2% (12/54) of all admissions. Most patients had a previous admission of over 28 days in duration (44.4%, 24/54), compared to those with a duration of under 28 days (16.7%, 9/54) and the majority were discharged home (59.3%, 32/54). Twenty-one patients had no previous inpatient admission (39%).

4 Discussion

This study presented the demographic, clinical and treatment characteristics of patients with ELOS in a private inpatient setting between 1st July 2018 and 30th July 2019.The characteristics of patients with ELOS highlighted the need for carefully considered admission and discharge planning to reduce the risk of extended length of stay. Clinical characteristics were similar to past research conducted in Australian private psychiatric hospitals [6], with respect to diagnosis of schizophrenia or psychotic illness (11.1% compared to 9.1% respectively). As expected, rates of these conditions were considerably higher in studies conducted in Australian public hospitals (39 and 69%) [5]. Interestingly, only 33.3% of patients in the present study had affective disorder diagnoses, given that past research in the same study setting indicated that mood disorders were present in 63% of patients [11]. This finding may indicate that affective disorders may not be associated with ELOS and that other diagnostic risk factors may be involved. Further comparisons to previous research can be viewed in Table 4 below.

Demographic results indicated that most patients were female (77.8%) which is consistent with past research on ELOS showing significantly longer psychiatric admissions for female than male patients [10]. It may be necessary to investigate if female patients require additional support in preparing for discharge or an increase in post-hospitalisation psychiatric treatment support in the community. It is important to note that the type of admission may determine whether ELOS is more likely to occur. Most ELOS admissions were of patients admitted under the general psychiatric unit, rather than to a specialised inpatient unit for planned therapy as part of the EMDR, OCD and eating disorder programs. At this hospital, these specialised therapy programs have planned start and end dates that likely assist with discharge planning. In contrast, private inpatients on general psychiatric wards may require admissions of greater length to treat acute exacerbations in psychiatric symptoms. This is also similar to patients requiring a public psychiatric admission where the focus of treatment is on acute stabilisation and safe discharge of patients [12].

The patients within the study sample displayed a high level of psychiatric complexity and severity. Most were administered between two and four psychotropic medications (regular and PRN) on admission (69.7%) and the average number of comorbid psychiatric conditions was 2 (SD = 6.69). Of note, the prevalence of physical health conditions was very high with 91% of patients having at least one comorbid physical health condition. This further supports the complexity of treatment needs in patients with multiple comorbidities who require prolonged psychiatric admissions, as well as the strong link between physical and mental ill-health. Previous research conducted at this private hospital found that the prevalence rate of one or more physical health conditions was 64.3% [13] and it is possible that the considerably higher prevalence of comorbid physical health conditions in the present study may be an indicator for ELOS. This prior research suggested appointing a dedicated physical health or cardiometabolic health nurse to work alongside existing general practitioner staff at the hospital. A nurse in this role would provide additional monitoring of patients at risk of or diagnosed with cardiometabolic health conditions and may improve patient flow and decrease extended length of stay. Future research may seek to further investigate whether physical comorbidity increases the risk of extended length of stay. Furthermore, identifying patients with high physical comorbidities and multiple psychiatric medications at the point of admission and engaging in early discharge planning should be considered to reduce length of stay. It may also be beneficial to have a hospital pharmacist and a second psychiatrist review the medication charts for patients on multiple psychiatric medications, with a view towards rationalisation if appropriate.

The characteristics of extended length of stay are multifactorial with many clinical and treatment considerations to be made when attempting to reduce extended length of stay admissions in this setting. The findings of this research can inform a review of admission and discharge planning and specialised treatment programs to reduce extended length of stay.

5 Study limitations

A key limitation of this research is that the analysis lacks a comparator group. The results however provide a comprehensive description of the patient, clinical and treatment characteristics in a sample of inpatients who had extended length of stay. Although we were unable to establish if these characteristics differ to those of a non-extended length of stay group, our results are consistent with the findings in the literature. A larger sample size which compares patient, clinical and treatment characteristics of ELOS to non-ELOS patients and the inclusion of patient-reported experiences would provide more substantive data for analysis. The non-parametric test performed in this study (chi square) did not produce statistical evidence of relationships between treatment, demographic and clinical characteristics and ELOS. This is likely due to the lower power of this non-parametric analysis compared to its parametric equivalents. The Pearson’s correlation coefficient test was performed, but it also did not provide any results of statistical significance, likely due to the small sample size. It is unknown whether the results are transferrable to other private or public settings or to other geographic areas within Australia, particularly rural and regional settings. As our study did not address the health economic aspects, future studies should conduct a cost analysis on the factors that cause ELOS as well as methods that reduce length of stay.

6 Clinical implications

Specific characteristics, such as female patients and those with physical health comorbidities and those taking multiple psychiatric medications are more likely to have ELOS in private psychiatric settings. Further studies on patients with ELOS are needed to ascertain if certain diagnoses and their severity are moderating factors for ELOS.

A designated protocol for identification of risk factors for ELOS would allow clinicians to provide targeted support when transitioning these patient groups back into the community. Future longitudinal study should also aim to investigate interventions for patients with risk factors for ELOS would result in improved treatment outcome or reduced readmission rates.

Data availability

The database for this study cannot be publicly shared due to patient confidentiality. A de-identified version of the database may be provided upon request.

References

Callaly T, Hyland M, Trauer T, Dodd S, Berk M. Readmission to an acute psychiatric unit within 28 days of discharge: identifying those at risk. Aust Health Rev. 2010;34(3):282–5. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH08721.

Royal Australian New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. Private Health Insurance. 2017. https://www.ranzcp.org/clinical-guidelines-publications/clinical-guidelines-publications-library/private-health-insurance-policies-for-psychiatry

Goldney RD, Costain WF, Jackson DE, Spence ND. A comparison of patients in private and public psychiatric facilities. Aust Clin Rev. 1988;8(30):117–23.

Keks NA, Hope J, Pring W, Damodaran S, Varma S, Adamopoulos V. Characteristics, diagnoses, illness course and risk profiles of inpatients admitted for at least 21 days to an Australian private psychiatric hospital. Australas Psychiatry. 2019;27(1):25–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856218804345.

Fenton K, Kingsbury A, Jayalath S. Improving patient flow on adult mental health units: a multimodal study of Canberra Hospital’s acute psychiatric facilities. Psychiatr Danub. 2017;29(suppl. 3):594–603.

Boot B, Hall W, Andrews G. Disability, outcome and case-mix in acute psychiatric in-patient units. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171(3):242–6. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.171.3.242.

Babalola O, Gormez V, Alwan NA, Johnstone P, Sampson S. Length of hospitalisation for people with severe mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000384.pub.

Swadi H, Bobier C. Hospital admission in adolescents with acute psychiatric disorder: how long should it be? Australas Psychiatry. 2005;13(2):165–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/j.1440-1665.2005.02181.x.

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453–7.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Specialised Mental Health Care Facilities. 2023. https://www.aihw.gov.au/mental-health/topic-areas/facilities

Botvinik L, Ng C, Schweitzer I. Audit of antipsychotic prescribing in a private psychiatric hospital. Australas Psychiatry. 2004;12(3):227–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/j.1039-8562.2004.02099.x.

Miller DA, Ronis ST, Slaunwhite AK. The impact of demographic, clinical, and institutional factors on psychiatric inpatient length-of-stay. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2021;48(4):683–94.

Nadjidai SE, Kusljic S, Dowling NL, Magennis J, Stokes L, Ng CH, Daniel C. Physical comorbidities in private psychiatric inpatients: prevalence and its association with quality of life and functional impairment. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2020;29(6):1253–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12764.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank medical staff Dr Anna Vaux and Dr Pheobe Hoo for their assistance with data collection for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SEN wrote the main manuscript text. LJ designed the research project protocol. LJ and GR collected data and LJ performed analysis of the data. Authors SEN, LJ, JAK, NLD, GR and CHN provided critical review and edited the manuscript. CNG is the senior author.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nadjidai, S.E., Jester, L., King, J.A. et al. Extended length of stay in an Australian private psychiatric hospital: an observational study of patient, clinical, and treatment characteristics. Discov Health Systems 3, 79 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44250-024-00143-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44250-024-00143-0