Abstract

Background

The exclusive breastfeeding rate in Sub-Saharan Africa is abysmally low, and based on current trends, achieving the World Health Organization's (WHO) global nutrition goal of a 50% exclusive breastfeeding rate by 2025 will require an additional three decades.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study involving healthcare workers (HCWs) providing direct care to breastfeeding mothers in six geopolitical zones in Nigeria. HCWs were recruited using a stratified random sampling method, with a minimum sample size of 1537. Data was collected through validated-interviewer-administered-questionnaires.

Results

The mean age of the 1294 respondents was 35.2 ± 10.0 years, with a male-to-female ratio of 1:3. Overall, breastfeeding knowledge was subsufficient (41.2% across three domains), with specific knowledge gaps observed in breastfeeding for mothers with breast cancer (13.4%) and hepatitis B (59.4%). Only 18.9% correctly identified laid-back and cross-cradle breastfeeding positions. High school and tertiary education were significantly associated with sufficient breastfeeding knowledge (AOR: 2.2, 95% CI 1.299–3.738; AOR: 2.0, 95% CI 1.234–3.205). Negative attitudes toward breastfeeding support were associated with being female (AOR: 1.5, 95% CI 1.094–1.957), while being a doctor was linked to the lowest instructional support (AOR: 0.3, 95% CI 0.118–0.661). Positive attitudes toward breastfeeding support were significantly associated with sufficient knowledge (AOR: 2.4, 95% CI 1.833–3.161; p < 0.001), but not with technical knowledge (AOR: 0.8, 95% CI 0.629–0.993).

Conclusion

Healthcare workers showed subsufficient overall breastfeeding knowledge, especially regarding breastfeeding in maternal illnesses and positioning. Targeted programs are needed to improve breastfeeding support knowledge, instructional support and attitudes, especially among female HCWs and physicians.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Breastfeeding is the most effective intervention for child survival in the perinatal period and beyond, with long-term benefits lasting a lifetime [1,2,3,4]. The unique composition of human milk, includes its content of stem cells with enormous potential, the microbiome, epigenetic factors such as micro ribonucleic acids and deoxyribonucleic acid methylation, the intricate interplay of nutrient variability based on maternal diets and stage of lactation, and a plethora of immunological factors such as antibodies, cytokines, and immune factors, makes it an unrivalled source of sufficient nutrients for the infant [5, 6]. The human milk is very rich in oligosaccharides, prebiotics, probiotics, postbiotics, and functional lipids that account for its easy digestibility, prevention of chronic diseases like diabetes and obesity, as well as ovarian and breast cancer in the mother [5, 7,8,9,10,11]. Besides, breastfeeding could save huge economic waste from the commercialization of formula feeds based on the misconception that recent advances in breastmilk substitutes make formula feeds comparable to human breast milk [6, 12].

Despite the obvious benefits of breastfeeding, the exclusive breastfeeding rate in the first 6 months in Sub-Saharan Africa remains abysmally low, with values ranging from 12 to 70%. Only about one-third of African countries (18 out of 49) are on track to meet the World Health Organization (WHO) global nutrition target to increase the rate of exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months up to at least 50% by 2025 [13,14,15]. Based on the current trend of a 6% increase in exclusive breastfeeding rates over 21 years (from 30% in 2008 to 36% in 2021), achieving the World Health Organization’s global target of 50% exclusive breastfeeding rates can take another three decades (2050) if pragmatic approach is not adopted.

In low-middle-income countries (LMICs), observed barriers to exclusive breastfeeding include inadequate antenatal care [16], delayed breastfeeding initiation, insufficient perinatal maternal breastfeeding support, and limited focused breastfeeding care at discharge and follow-up. With sufficient breastfeeding support, it is possible to overcome all of these barriers and constraints [13, 14]. On this premise, the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that healthcare workers provide breastfeeding support to mothers during the first ten days after delivery, with the first two days being the most critical[2, 15]. This further emphasizes the central role healthcare personnel play in promoting appropriate breastfeeding practices. Published literature [1, 2] have demonstrated that health facilities that implement the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative were found to have higher rates of exclusive breastfeeding and longer durations of breastfeeding practices [1, 2].

Breastfeeding support (BFS) involves providing mothers with the information, and practical skill assistance needed to breastfeed successfully. It encompasses the combined efforts made by all stakeholders to adequately offer the right assistance and appropriate facilities to breastfeeding mothers. Healthcare workers including doctors, nurses, midwives, and International Board-Certified Lactation Consultants, are in a unique position to provide this support, as they often have frequent and extended contact with mothers during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period. In addition, this assistance cannot be in isolation as the husband, family and community also play significant roles.

However, the roles of health workers in implementing breastfeeding support in low-income settings are of particular interest. This is due to the undeniable need for health workers to provide breastfeeding support services during the ante, peri, and post-natal periods for mother and baby to have a successful breastfeeding relationship. The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative’s (BFHI) ten steps to successful breastfeeding neatly sum up these services and supports [17].

Although breastfeeding support has been demonstrated to be an effective intervention for increasing breastfeeding rates, little attention has been paid to the quality of breastfeeding support provided to nursing women in LMICs in order to maximize the impact of this nutrient-dense, eco-friendly, and cost-effective feeding option.

The awareness, attitudes and practices of healthcare workers concerning breastfeeding can significantly affect breastfeeding outcomes for both mothers and their infants. Healthcare workers’ awareness and knowledge of the benefits of proper breastfeeding techniques are essential for providing effective support to mothers [18]. Healthcare workers must be well-informed of the most recent research evidence and recommendations on breastfeeding to be able to translate such evidence-based care to mothers. This includes understanding the health benefits of breastfeeding for both mothers and infants, recognizing the signs of successful breastfeeding, and being able to identify and address common breastfeeding problems. They must ensure that bonding and attachment are skillfully supported. It is also their responsibility to prevent circumstances that result in mother-baby separation and provide a link to maternal support groups with ‘breastfeeding champions’ and hotlines for mothers to call when they require support after being discharged from the hospital. Similarly, a positive or negative attitude of healthcare workers towards breastfeeding can either encourage or discourage mothers to initiate and sustain breastfeeding. Healthcare workers’ assistance with proper positioning and attachment techniques, as well as continual reassurances throughout their breastfeeding journey, cannot be overemphasised.

Currently, there is a dearth of nationally representative data on which to base a strategic plan for an effective breastfeeding support program. Evidence-based policies from formative research are required to address barriers implement facilitators to exclusive breastfeeding in modern medicine. These policies are a work in progress, with the need for ongoing monitoring and evaluation, as well as the need to update practices based on progress made. Assessing healthcare workers' awareness of, attitudes towards, and practices regarding breastfeeding support is critical to reversing the current trend and rolling back the long-term health damage done to the next generation of babies. Baseline data will be required to inform policy formulation and a review of the current national breastfeeding action plan as the country moves towards updating its breastfeeding action plan.

This study, therefore, aimed to assess the awareness of, attitudes towards, and practices regarding breastfeeding support for breastfeeding mothers among healthcare workers in Nigeria. It is hoped that data from this study will provide information for pragmatic and targeted intervention in this regard to improve breastfeeding uptake.

2 Subjects and methods

2.1 Study design

This was a nationwide cross-sectional study involving the six geo-political zones in Nigeria. The study was conducted between August 2022, and February 2023.

2.2 Study settings

The study was hospital-based, with participants from both private and public hospitals. Although the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative was established in Nigeria in 1991, following the Innocenti Declaration in 1990, marking 33 years since its inception [19]. Despite the introduction of auxiliary programs aimed at enhancing its adoption, the initiative continues to be underutilized. In fact, as of 2017, the implementation rate of the Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative in African countries, including Nigeria, was reported to be less than 5% [20]. Due to this persistently low uptake, the National Ministry of Health initiated the development of adapted guidelines in 2019. These guidelines were crafted by the nutrition division and other stakeholders to include locally relevant content, signifying a concerted effort to tackle this challenge. It is important to emphasize that all participating centers in this study were designated as Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) facilities by the WHO, yet there is a notable absence of regular reassessments. Additionally, while some centers provide training on breastfeeding support to both new and existing staff, there remains a deficiency in conducting routine quality checks on the breastfeeding competencies of healthcare workers.

The participating health workers, with the exception of community health extension workers, offer services to breastfeeding mothers at either Level 2 or Level 3 facilities, as per the WHO criteria in the Nigerian Comprehensive Newborn Guidelines for designating healthcare service levels. Community health extension workers typically operate at Level 1 facilities, providing primary healthcare services [21].

2.3 Study population

Health workers, including doctors, nurses, midwives, hospital attendants, dieticians, community health extension workers, and lactation consultants, were recruited to participate in the study. These participants are directly involved in providing care to breastfeeding mothers at various healthcare settings such as ante-natal clinics, delivery rooms, post-natal wards, immunization clinics, neonatal wards, pediatric clinics, and primary and secondary facility clinics across Nigeria.

Health workers at all levels receive some form of training on breastfeeding support, either through formal training or on-the-job training. However, there is no routine assessment of breastfeeding competencies across all levels of training.

2.4 Eligibility criteria

2.4.1 Inclusion criteria

In-service healthcare professionals who attend to breastfeeding mothers in Nigerian hospitals.

2.4.2 Exclusion criteria

-

1.

Healthcare workers recently redeployed or a healthcare worker who has been assigned to a newborn unit for less than 6 months.

-

2.

Healthcare workers who work in the newborn unit but are not in active service for at least 6 months.

2.5 Sample size determination

To obtain the maximum sample size for the study on breastfeeding support knowledge, attitude, and practice among in-service health workers, we estimated a 50% prevalence of sufficient breastfeeding support practices. Utilising Raosoft software, a minimum sample size of 1537 was determined at a margin of error of 2.5% and an alpha level of probability of 0.05.

2.6 Sampling techniques

The participants for the study were selected using a single-stage stratified simple random sampling method. In-service Nigerian hospital healthcare workers (nurses, midwives, nursing assistants, hospital maids, community health extension workers, dieticians, and breastfeeding champions) who provide services to pregnant women, breastfeeding mothers, and infants at ANCs, paediatrics wards and clinics, labour wards, lying-in wards, immunisation centres, private hospitals, and postnatal wards and clinics were identified.

The sample size was proportionally distributed among eligible health workers based on ratios of 6:2:1:1:1 for nurses, hospital maids/nursing assistants, doctors, dieticians, and other supporting health workers based on the 2018 National Demographic Survey [19]. To gain their support, the sectional heads of the various cadres of healthcare workers were contacted and briefed on the research. An interviewer-administered questionnaire was employed to obtain data from study participants.

2.7 Development of research questionnaire

The survey questionnaire was developed for a large ongoing clinical research on breastfeeding medicine. A group of Paediatricians and Neonatologists used the WHO Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative's ten steps to successful breastfeeding (BFHI) and BFI 20 Hour Course: clinical Practice Options as well as other published literature as a guide to develop the questionnaire [17, 22]. The questionnaire was face validated. In a pilot study involving 50 participants, the questionnaire was evaluated for its suitability. Following the completion of the pilot survey, the team modified the questionnaire based on public feedback. The results of the pilot study were analysed and a Cronbach alpha score of 0.8 was obtained. In addition, the questionnaire was validated by five public health specialists. At the beginning of the questionnaire, the respondent voluntarily provided consent; if “NO” was selected as a response, the participant will exit the survey. There were three sections within the questionnaire. Section A examined the sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants and their knowledge of breastfeeding support. Using questions adapted from the Lactation-Specific Care Questionnaire, Section B evaluated the attitudes of healthcare professionals toward breastfeeding support, whereas Section C examined the In-service healthcare professionals on practical breastfeeding support skills. The questionnaire is attached as a supplementary document (Suppl. Questionnaire 1).

2.8 Data management and analysis

Data were entered into a Microsoft Access file and analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (S.P.S.S) version 23. The ages of the participants were summarised as mean and standard deviation while the discrete variables were summarised as frequency and percentages. For categorical variables (with a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response), percentages of correct answers were reported for general breastfeeding knowledge and breastfeeding support knowledge. Differences in proportion were compared for significance using the Chi-square test or Fischer’s exact. The 5-point Likert scale was dichotomized with ‘at least agreed’ as the threshold for a positive response, and the results were reported using frequency tables and percentages [23]. In addition, the mean of the total responses on the 5-point Likert scale for breastfeeding support knowledge and breastfeeding attitude were calculated.

The mean scores for each knowledge domain, including general, technical, and support aspects, were computed. The criterion for sufficient knowledge was set at a score of 3.25 on a 5-point scale, corresponding to 70% on the scale [24]. This threshold aligns with the recommended cut-off established by the Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations of 70%, in accordance with the recommendation by the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations using the guidelines for assessing nutrition related knowledge, attitudes, and practices and was also chosen for comparison with similar published literature [24, 25]. To determine an overall sufficient knowledge score regarding breastfeeding, the summary score from the three knowledge domains was considered. An aggregate score of 70% or more was defined as sufficient overall knowledge of breastfeeding [24]. Regarding instructional support for breastfeeding, on a 5-point Likert scale, the lowest response was grade 1 for never, and the highest response was grade 3 for always. Scores above the 2.1 or 70% were deemed sufficient, while scores below the mean were deemed insufficient for breastfeeding instructional support [24]. The predictor variables (such as age, gender, educational attainment, and levels of healthcare practice (primary, secondary, and tertiary), workplace (private or public sector), healthcare specialist, study location, and clinical practice years] for breastfeeding support were determined by using multivariable logistic regression and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) reported. For all levels of statistical significance, the p-value was set at < 0.05.

2.9 Ethical considerations

The study received ethical approval from Nigeria’s National Health Research Ethics Committee (NHREC/01/01/2007–26/08/2022). This research was carried out following the Helsinki Declaration [26]. The participants were informed about the study before providing their informed consent. To ensure privacy, the data was redacted, password-protected and confidentiality was maintained throughout the study.

3 Results

3.1 General characteristics of the study participants

A total of 1294 participants were recruited across all six geopolitical zones in Nigeria. The mean (standard deviation) age of the respondents was 35.2 (10.0) years and most were females (977; 75.5%). Almost half of the participants were aged 31–50 years (48.8%). Table 1 shows that most of the participants had a tertiary level of education (1227; 94.8%), work at tertiary health facilities (71.8%), and from public hospitals (85.5%). About half (48.0%) of the study participants were nurses and midwives. Based on the geopolitical zones of the participants, the Southwest had the highest (26.6%) representation. Further details are shown in Table 1. Figure 1 provide a visual overview of the results, for clear understanding.

3.2 Overall breastfeeding knowledge

Breastfeeding knowledge across all three assessed domains was found to be inadequate with a summary score 41.2%. Specifically, only 41.0% of healthcare workers (HCWs) demonstrated sufficient general knowledge, 42.2% exhibited sufficient technical knowledge, and a notable (79.7%) showcased adequate understanding of breastfeeding support (Table S1).

3.3 Knowledge of breastfeeding: general, technical and support

Only two-thirds of HCWs (63.8%) accurately defined exclusive breastfeeding and were familiar with the baby-friendly hospital initiative (63.9%). When it came to maternal health and breastfeeding (Fig. 2), 75% had the correct knowledge about breastfeeding for HIV/AIDS-positive mothers, and 59% for hepatitis B-positive mothers. However, awareness of breastfeeding in mothers with breast cancer was notably low (13.4%). While breastfeeding technique knowledge was generally fair, fewer than one-fifth of HCWs (18.9%) correctly identified laid-back and cross-cradle positions.

With respect to breastfeeding support knowledge, only 45.1% agreed that dummies/pacifiers should not be used for breastfeeding babies. Of the 1294 participating HCWs, 85.7% agreed that not providing breastfeeding support could lead to early breastfeeding cessation. Figure 3 provides more information.

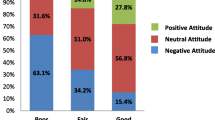

4 Healthcare workers’ attitudes towards breastfeeding and breastfeeding support

Only 641 of HCWs (49.5%) held a positive attitude toward the importance of HCWs managing common breastfeeding problems, while less than a third (27.2%) considered the baby-friendly initiative burdensome. While 93.8% of respondents ‘at least agreed’ that healthcare workers’ support is advantageous for working mothers in promoting exclusive breastfeeding, it is notable that only two-thirds (63%) ‘at least agreed’ that early breastmilk supplementation may potentially reduce milk supply (Fig. 4).

4.1 Breastfeeding practice regarding instructional support

The primary forms of support provided by HCWs to breastfeeding mothers were direct instruction (93%) and educating them on breastfeeding benefits (91%). Only 60% of HCWs also offered breastfeeding assistance to both mothers and their families. Figure 5 provides additional details.

4.2 Factors associated with sufficient overall breastfeeding knowledge

The overall knowledge of healthcare workers (HCWs) regarding breastfeeding exhibits no statistically significant differences in relation to age, gender, or educational background. Health workers in secondary (AOR: 2.2, 95% CI 1.299–3.738, p = 0.003) and tertiary (AOR: 2.0, 95% CI 1.234–3.205) health facilities demonstrated better overall knowledge of breastfeeding compared to those in primary health facilities. The deficiency in knowledge was consistent across all health worker cadres, including doctors, nurses, health attendants, and dieticians, with no significant variations.

Geographically, about 50% of health workers in the northeastern geopolitical zone of the country demonstrated poor breastfeeding knowledge (AOR: 0.50, 95% CI 0.313–0.941, p = 0.029) compared to those in the other six geopolitical zones. The years of clinical experience contrarily had no discernible effect on health workers' overall knowledge of breastfeeding. Additional information are on (Table 2).

4.3 Factors associated with negative attitude towards breastfeeding

Among the explanatory variables considered in logistic regression, including age, level of education, tier of health facility, and whether in the private or public sector, only gender showed a significant association with a negative attitude toward breastfeeding. Specifically, females (AOR: 1.5; 95% CI 1.094, 1.957, p = 0.010) demonstrated approximately a 50% increased odds of being averse to breastfeeding compared to males. Moreover, health workers in the northwestern region of the country (AOR: 1.5; 95% CI 1.094, 1.957, p = 0.010) displayed an elevated likelihood of harbouring a negative attitude toward breastfeeding (Table 3).

4.4 Factors associated with breastfeeding sufficient instructional support by In-service health workers

Adequate instructional support for breastfeeding among health workers was significantly associated with tertiary-level education (AOR: 5.3; 95% CI 1.681, 16.764; p = 0.004). Medical doctors provided the poorest support (AOR: 0.3; 0.118, 0.661; p = 0.004), trailing even behind ward attendance (AOR: 0.4; 0.129, 0.875; p = 0.025) and other health worker cadres (AOR: 0.3; 0.089, 0.747; p = 0.012), excluding dieticians, community health extension workers, and nurses.

Furthermore, health workers in the Southwestern part of the country demonstrated a higher likelihood of sufficient instructional support (AOR: 1.71; 95% CI 1.061, 2.701; p = 0.027) as shown in Table 4.

4.5 Relationship between attitude (positive) and sufficient knowledge of breastfeeding

In the assessment of the three knowledge domains—general, technical, and support—a positive attitude towards breastfeeding by HCWs had a significant association with sufficient knowledge of breastfeeding support (AOR: 2.4; 95% CI 1.833, 3.161; p = < 0.001). Conversely, a positive attitude towards breastfeeding was linked to a 20% reduction in the odds of having sufficient technical knowledge of breastfeeding (AOR: 0.8; 95% CI 0.629, 0.993).

While an initial association was noted between a positive HCWs’ attitude to breastfeeding and the provision of instructional material for breastfeeding support to mothers (COR: 1.4; 95% CI 1.027, 1.665), this association became attenuated upon adjusting for confounders. Other details are in Table 5.

5 Discussion

This study assessed breastfeeding support awareness, attitudes, and practices among Nigerian in-service healthcare workers. We observed a significant deficiency in breastfeeding support knowledge across all three domains evaluated, with the most notable gaps concerning maternal health and breastfeeding, instrumental support, particularly in various breastfeeding positions. Female healthcare workers displayed reluctance towards breastfeeding support, while physicians demonstrated the weakest knowledge in providing instructional support for breastfeeding mothers.

The significant deficiency in breastfeeding support knowledge observed among healthcare workers is consistent with previous research indicating a lack of proper training and education in breastfeeding support [27]. A number of studies have found that healthcare personnel lack knowledge regarding breastfeeding management, including best practices, common problems, and effective support measures [27, 28]. This lack of understanding can lead to low breastfeeding rates and stymie efforts to promote breastfeeding as an essential component of newborn nutrition and maternal health.

Our findings of the worse performance in areas of maternal illnesses: maternal infections such as hepatitis and HIV, as well as maternal malignancies, with breast cancer being the most prevalent malignancy in women, suggests a potential barrier to actively supporting and aiding mothers in sustaining breastfeeding while undergoing treatment for these specific conditions. Inadequate breastfeeding support can lead to premature weaning, which has an impact on both maternal and infant health outcomes [29]. The inability of healthcare workers (HCWs) to identify specific breastfeeding positions and their respective indications is also concerning, as previous studies have highlighted the significant impact of poor attachment and positioning of breastfeeding mothers as formidable barriers to successful breastfeeding [30, 31].

This gap is particularly concerning, given that a substantial portion of the participants are from tertiary hospitals, often sought out for their expertise and leading-edge practices. If healthcare professionals, who are entrusted with an excellent grasp of fundamental principles, fail to demonstrate the expected level of expertise, it raises serious concerns about the quality of education provided to lay mothers who lack specialised training. This highlights the critical need for targeted interventions, such as raising awareness and implementing breastfeeding support protocols endorsed by the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine in various settings of maternal illnesses and other breastfeeding medicine moderating bodies [17, 32, 33]. This also calls for ongoing education and enhanced training for healthcare professionals as advocated by the World Health Organization in order to effectively support breastfeeding mothers who are facing challenging health conditions [32, 34]. Recognizing that knowledge fuels skills, and skills, in turn, enhance knowledge, conducting a thorough assessment across all facets of breastfeeding support utilizing the revised Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative competency evaluation would be pivotal as an initial step in crafting effective, focused interventions [17].

The reluctance to provide breastfeeding support reported among female healthcare professionals is a notable result supporting earlier reports on gender differences in breastfeeding attitudes and behaviours. Cultural norms, societal expectations, and personal experiences can all impact women’s attitudes about breastfeeding, including their readiness to assist nursing mothers [35, 36]. Addressing the underlying causes of this hesitancy, such as cultural constraints or a lack of institutional support, is critical for enabling female healthcare workers to embrace their role in promoting breastfeeding.

The finding that physicians had the least competence in providing instructional support for nursing mothers is consistent with earlier studies revealing inadequacies in medical education and training on breastfeeding [37, 38]. This encompassed insufficient guidance on using breast pumps, inadequate instructions on non-nutritive suckling for preterm infants, and a lack of information sheets on breastfeeding support. Despite its significance for mother and child health, breastfeeding instruction is frequently restricted or insufficiently incorporated into medical school curriculum and postgraduate training programmes. It is crucial to recognise that in low- and middle-income countries such as Nigeria, superspecialization in breastfeeding medicine is rare and neonatal nursing is still at a rudimentary level. Consequently, there arises a pressing need for medical councils in these countries to review the teaching curriculum and collaborate with their counterparts in high-income countries to provide training for healthcare practitioners in breastfeeding medicine, ultimately promoting exclusive and extended breastfeeding.

The finding of health workers’ positive attitudes towards breastfeeding and a lack of alignment with adequate technical expertise presents an intriguing paradox. This implies that the factors influencing these variables are diverse, emphasising the importance of conducting a comprehensive and nuanced assessment of breastfeeding support competencies. While emotional factors, awareness of the benefits, and societal encouragement all have an impact on attitudes, technical knowledge is primarily acquired through professional training and specialisation in breastfeeding medicine. A comprehensive breastfeeding support programme should offer clear guidance on techniques, positions, and practices, along with practical knowledge for proper latching and infant feeding. Additionally, addressing emotional and psychological aspects is crucial for empowering individuals, fostering confidence, and facilitating discussions on concerns and challenges [39, 40].

The updated WHO-UNICEF BFHI reinforces healthcare worker competencies and counselling skills, as well as comprehensive breastfeeding knowledge, in order to improve breastfeeding support. It is imperative to enhance national implementation efforts to augment HCW competencies and counseling capacity, thereby fostering improved breastfeeding support. Effective counselling necessitates establishing a dialogue between healthcare providers and patients that is characterised by active listening, empathetic communication, and the exploration of patients' views, understandings, beliefs, and emotions. This tailored approach would not only address the physical aspects of breastfeeding, but also the psychological, social, and emotional dimensions of care, encouraging overall well-being and patient-centered support within the breastfeeding context [39, 40].

The WHO has made available a range of online resources aimed at enhancing breastfeeding practices. These resources include breastfeeding support counseling guidelines, a competency verification toolkit, and implementation guidance for promoting breastfeeding in maternity and newborn care facilities. These materials are not only intended for healthcare workers but also for policymakers and national managers of maternal and child health programs related to the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) [41,42,43]. They serve as valuable reference materials for individuals involved in maternal, fetal, and infant health to enhance outcomes.

5.1 Study strength and limitation

Our study, like every other research, has its own strengths and limitations. One of the study’s significant strengths is its multicenter nature and fairly large sample size, which enhances the study’s statistical power and provide a more representative picture of breastfeeding support awareness, attitudes, and practices among a broader population of healthcare workers. Additionally, the study’s comprehensive scope enables a deeper understanding of the factors influencing breastfeeding support among healthcare workers, yielding valuable insights.

However, being a cross-sectional study, despite the large sample size, it may only capture a snapshot of variables and practices at a specific point in time, limiting our ability to establish causality or observe changes over time. Moreover, the reliance on self-reported data could introduce social desirability bias, potentially leading participants to provide responses they perceive as socially expected rather than expressing their true attitudes and practices. We recognize that the questions related to knowledge assessment, especially in the field of counseling, may be perceived as being inexhaustive. This is an important aspect to take into account for future research endeavors. Furthermore, the study’s predominantly tertiary-centred focus may introduce sampling bias, which could impact the generalizability of our findings to a more diverse healthcare worker population.

Nevertheless, our study lays the groundwork for future research on breastfeeding support among in-service healthcare workers, particularly in light of the significant migration of skilled health workers post-COVID-19, which has resulted in limited replacements [44]. By recognising its strengths and limitations, we hope that future investigations can build upon this foundation, employing longitudinal designs and more diverse sampling techniques to overcome the identified limitations and further contribute to this vital area of research.

6 In conclusion

Healthcare workers lack essential breastfeeding knowledge, particularly in maternal illnesses and positioning. Targeted programs are necessary to enhance support knowledge, counseling techniques, and attitudes, especially among female HCWs and physicians. These findings can guide interventions to improve breastfeeding support among Nigerian healthcare workers.

Data availability

The data is available to editors, reviewers and readers without any restriction when required.

References

Kinshella M-LW, Prasad S, Hiwa T, Vidler M, Nyondo-Mipando AL, Dube Q, et al. Barriers and facilitators for early and exclusive breastfeeding in health facilities in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Glob Heal Res Policy. 2021;6(1):1.

Fox R, McMullen S, Newburn M. UK women’s experiences of breastfeeding and additional breastfeeding support: a qualitative study of Baby Café services. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0581-5.

Van Dellen S, Wisse B, Mobach MP, Dijkstra A. The effect of a breastfeeding support programme on breastfeeding duration and exclusivity: a quasi-experiment. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):993.

Joseph FI, Earland J. A qualitative exploration of the sociocultural determinants of exclusive breastfeeding practices among rural mothers. North West Nigeria Int Breastfeed J. 2019;14(1):1–11.

Bardanzellu F, Peroni DG, Fanos V. Human breast milk: bioactive components, from stem cells to health outcomes. Curr nutr report. 2020;9:1–13.

Falcão MC, Zamberlan P. Infant Formulas: a long story. Inter J Nutro. 2021;14:e61–70.

Tingö L, Ahlberg E, Johansson L, Pedersen SA, Chawla K, Sætrom P, et al. Non-coding RNAs in human breast milk: a systematic review. Front Immunol. 2021;12: 725323.

Horta BL, Loret de Mola C, Victora CG. Breastfeeding and intelligence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104:14–9.

Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ, França GV, Horton S, Krasevec J, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387:475–90.

Witkowska-Zimny M, Kaminska-El-Hassan E. Cells of human breast milk. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2017;22:1–11.

Mischke M, Plösch T. More than just a gut instinct–the potential interplay between a baby’s nutrition, its gut microbiome, and the epigenome. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;304:R1065–9.

Miqdady M, Al Mistarihi J, Azaz A, Rawat D. Prebiotics in the infant microbiome: the past, present, and future. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2020;23:1.

Bhattacharjee NV, Schaeffer LE, Marczak LB, Ross JM, Swartz SJ, Albright J, et al. Mapping exclusive breastfeeding in Africa between 2000 and 2017. Nat Med. 2019;25:1205–12.

Zamora G, Lutter CK, Pena-Rosas JP. Using an equity lens in the implementation of interventions to protect, promote, and support sufficient breastfeeding practices. J Hum Lact. 2015;31:21–5.

Doherty T, Horwood C, Haskins L, Magasana V, Goga A, Feucht U, et al. Breastfeeding advice for reality: women’s perspectives on primary care support in south Africa. Matern Child Nutr. 2020;16(1):e12877.

Iliyasu Z, Galadanci HS, Emokpae P, Amole TG, Nass N, Aliyu MH. Predictors of exclusive breastfeeding among health care workers in urban Kano. Nigeria J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2019;48:433–44.

World Health Organization. (2020) Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative training course for maternity staff: customisation Guide. 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240008915, Accessed on 15 May 2023

Marinelli KA, MorenTaylor and The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine JS K. Breastfeeding support for mothers in workplace employment or educational settings: Summary statement. Breastfeed Med. 2013;8:137–42.

National population commission. Nigeria demographic and health survey. 2018.

World Health Organization. National implementation of the Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative, Geneva. 2017

Federal ministry of health and social welfare, Federal Republic of Nigeria. National Guideline for comprehensive newborn care: Family Health Policy Documents; Federal Ministry of Health. 2023. https://health.gov.ng/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=158&Itemid=0. Accessed on Mar 23 2023

World Health Organization (WHO). Nutrition and Food Safety.Ten steps to successful breastfeeding. 2020. https://www.who.int/teams/nutrition-and-food-safety/food-and-nutrition-actions-in-health-systems/ten-steps-to-successful-breastfeeding. Accessed on May 13 2023.

Capik C, Gozum S. Psychometric features of an assessment instrument with likert and dichotomous response formats. Public Health Nurs. 2015;32:81–6.

Marías YF, Glasauer P. Guidelines for assessing nutrition-related knowledge, attitudes and practices. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2014.

Jain S, Thapar RK, Gupta RK. Complete coverage and covering completely: breast feeding and complementary feeding: Knowledge, attitude, and practices of mothers. Med J Armed Forces India. 2018;74(1):28–32.

World Medical Association. World Medical Association declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053.

Pérez-Escamilla R, Martinez JL, Segura-Pérez S. Impact of the baby-friendly hospital Initiative on breastfeeding and child health outcomes: a systematic review. Matern Child Nutr. 2016;12(3):402–17.

Balogun OO, Dagvadorj A, Anigo KM, Ota E, Sasaki S. Factors influencing breastfeeding exclusivity during the first 6 months of life in developing countries: a quantitative and qualitative systematic review. Matern Child Nutr. 2015;11(4):433–51.

World Health Organization (WHO). HIV and infant feeding: a guide for health-care managers and supervisors. World Health Organization. 2016. https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/9241591226/en/

Riaz A, Bhamani S, Ahmed S, Umrani F, Jakhro S, Qureshi AK, et al. Barriers and facilitators to exclusive breastfeeding in rural Pakistan: a qualitative exploratory study. Inter Breastfeed J. 2022;17:1–8.

Nduagubam OC, Ndu IK, Bisi-Onyemaechi A, Onukwuli VO, Amadi OF, Okeke IB, et al. Assessment of breastfeeding techniques in Enugu, south-east Nigeria. Ann Afr Med. 2021;20:98.

Johnson HM, Mitchell KB, AoB M. ABM clinical protocol# 34: breast cancer and breastfeeding. Breastfeed Med. 2020;15:429–34.

Bartick M, Hernández-Aguilar MT, Wight N, Mitchell KB, Simon L, Hanley L, Meltzer-Brody S, LawrenceAcademy of Breastfeeding Medicine RM. ABM clinical protocol# 35: supporting breastfeeding during maternal or child hospitalization. Breastfeed Med. 2021;16(9):664–74.

Helewa M, Levesque P, Provencher D, Lea RH, Rosolowich V, Shapiro HM. Breast cancer, pregnancy, and breastfeeding. J Obstet Gynaecol Can: JOGC. 2002;24:164–80.

Stevens EE, Patrick TE, Pickler R. A history of infant feeding. J Perinat Educ. 2009;18(2):32–9.

Jesus PC, Oliveira MI, Fonseca SC. Impact of health professional training in breastfeeding on their knowledge, skills, and hospital practices: a systematic review. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2016;92:436–50.

Health UDo and Services H. Executive summary the surgeon general’s call to action to support breastfeeding. Breastfeed Med. 2011;6:3–5.

Biggs KV, Fidler KJ, Shenker NS, et al. Are the doctors of the future ready to support breastfeeding? a cross-sectional study in the UK. Inter Breastfeed J. 2020;15:46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-020-00290-z.

Leshi OO, Makanjuola MO. Breastfeeding knowledge, attitude and intention of nursing students in Nigeria. Open J Nurs. 2022;12:256–69.

Alamirew MW, Bayu NH, Birhan Tebeje N, Kassa SF. Knowledge and attitude towards exclusive breast feeding among mothers attending antenatal and immunization clinic at dabat health center northwest Ethiopia a cross-sectional institution-based study. Nurs Res Pract. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/6561028.

World Health Organization. Guideline: counselling of women to improve breastfeeding practices. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

World Health Organization 2020. Competency verification toolkit ensuring competency of direct care providers to implement the baby-friendly hospital initiative. web annex D: examiner’s resource (sorted by BFHI step), Geneva.

World Health Organization. Guideline: protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding in facilities providing maternity and newborn services. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

Yakubu K, Shanthosh J, Adebayo KO, Peiris D, Joshi R. Scope of health worker migration governance and its impact on emigration intentions among skilled health workers in Nigeria. PLOS glob public health. 2023;3(1): e0000717.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Alao Michael Abel: substantially contributed to conception or design; contributed to acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; drafted the manuscript; critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content; gave final approval; agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions relating to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Rasheed Olayinka Ibrahim and Datonye Christopher Briggs: substantially contributed to the design, analysis, and interpretation of data; critically revised manuscript; gave final approval; agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy. Contributed to the design, drafting of the manuscript, critically revised manuscript; gave final approval; agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy. Sakiru Abiodun Yekinni, Chisom Adaobi Nri-Ezedi, Sikirat Adetoun Sotimehin, Yetunde Toyin Olasinde, Rasaki Aliu, Ayodeji Mathew Borokinni, Jacinta Chinyere Elo-Ilo, Oyeronke Olubunmi Bello, Udochukwu Michael Diala, Joyce Foluke Olaniyi-George, Temilade Oluwatoyosi Adeniyi, Usman, Hadiza Ashiru: Contributed to the design, critically revised manuscript; gave final approval; agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy. Olukemi Oluwatoyin Tongo: A mentor, contributed to the design, critically revised manuscript; gave final approval; agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by The Nigeria’s National Health Research Ethics Committee (NHREC/01/01/2007–26/08/2022).

Statement of methods and guideline compliance

We ensured that the researchers adhered to NHREC Approved Protocol Number NHREC/01/01/2007–13/08/2022. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Informed consent

After reviewing the consent form, the interviewer assessed the participant’s comprehension. Only those who showed a clear understanding were invited to provide electronic informed consent by selecting ‘Yes’ on the electronic form, in compliance with approval from Nigeria’s National Health Research Ethics Committee. If ‘No’ was chosen, they were excluded from further participation in the study.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alao, M.A., Ibrahim, O.R., Briggs, D.C. et al. Breastfeeding support among healthcare workers in Nigeria. Discov Health Systems 3, 46 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44250-024-00094-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44250-024-00094-6