Abstract

Background

Insufficient physical inactivity and an unhealthy diet are significant health risk factors globally. Dietary risk factors were responsible for approximately 16.5% of all deaths in Iran in 2019. This paper aimed to propose a dietary policy package for the health sector to reduce the risk of an unhealthy diet, which might effectively help prevent and control non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in Iran.

Methods

In this qualitative study, we conducted semi-structured, face-to-face, and in-depth interviews with 30 purposefully selected experts, including policymakers, high-level managers, and relevant stakeholders, during 2018–2019 in Iran. All interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim, and thematically analyzed, facilitated by MAXQDA 11 software.

Results

We developed several dietary recommendations for different stakeholders. These include traffic light labeling reforms, i.e., the need to make the signs large and readable enough through utilizing advanced technology, cooperation with other sectors, promoting healthy symbols and supporting food products with them, food basket reforms, updating dietary standards, adopting appropriate mechanisms to report violations of harmful products laws, scaling up mechanisms to monitor restaurants and processed foods, and creating an environment for ranking restaurants and other relevant places to support a healthy diet, for instance through tax exemption, extra subsidies for healthy products, Non-Government Organizations (NGOs) alliances, and using influential figures.

Conclusion

Iran’s health sector has developed a practical roadmap for the prevention and control of NCDs through promoting healthy nutrition. In line with the sustainable development goal (SDG) 3.4 pathway to reduce premature mortality due to NCDs by 30% by 2030 in Iran, we advocate for the Ministry of Health and Medical Education (MoHME) to adopt appropriate evidence-informed interventions for improving public health literacy and reducing consumption of unhealthy food.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Background

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) killed 42 million people in 2019 (over 74% of the global deaths) [1]. The top NCDs with the highest mortality are cardiovascular diseases, cancers, respiratory diseases, and diabetes [2]. In descending order, the most significant risk factors of NCDs are an unhealthy diet, inadequate physical inactivity, tobacco use, and the harmful use of alcohol [3, 4]. A rising concern has been developed that poor diet increases the potential risk of chronic diseases and diet problems in society [5]. Consuming processed meat and sugar-sweetened beverages in large amounts, besides other unhealthy lifestyle factors, i.e., smoking, a high body mass index (BMI), and physical inactivity is associated with a greater risk for NCDs [6]. Improvement in diet would prevent 20% of deaths worldwide [7]. In response to the NCDs’ burden, as part of its efforts to address behavioral and physiological risk factors for NCDs, the World Health Organization (WHO) has confirmed a set of nine voluntary targets, i.e., reducing salt intake by 30% and a 25% relative reduction of overall mortality from NCDs by 2030 [8].

WHO reported 82% of mortality in Iran due to NCDs (43% cardiovascular diseases, 16% cancers, and 23% other NCDs) in 2020, as the biggest public health concern in the country, imposing a considerable burden on Iran’s health system [9]. Table 1 provides information about Iran’s demographic indicators [10]. Eighty percent of the primary causes of death in Iran are attributed to NCDs. Dietary risk factors are the primary cause of NCDs in Iran. Dietary risk factors were responsible for approximately 16.5% of all deaths in Iran in 2019 [11]. The prevalence of an unhealthy diet in Iran is attributed to certain habits, such as high consumption of salt and saturated oils [12], hence the vital need for promoting a healthy diet through reducing calories, salt, sugar, and saturated fatty acid intake at the individual and industrial levels [13, 14]. Iran's health sector has implemented several industrial and population interventions to decrease NCDs' mortality and related problems [15, 16]. In 2012, the Community Nutrition Office affiliated with the Ministry of Health and Medical Education (MOHME) developed the National Nutrition and Food Security Policy (NNFSP) in collaboration with other stakeholders. This office has several duties, i.e., evaluation of nutrition and food security status at the community level, raising cultural awareness and nutrition literacy within the community, planning to reduce food insecurity and malnutrition, and promoting healthy nutrition among the general population [17], despite all the challenges in effectively addressing nutritional issues [18]. Besides, other countries have highlighted the health sector’s key role in minimizing NCDs and increasing population well-being at the individual and organizational levels [19]. Despite several accomplishments in the prevention and control of NCDs, dietary risk factors as the primary cause of NCDs cause a lot of mortality in Iran. This paper aimed to propose a policy package to reduce the risks of an unhealthy diet, aiming to prevent and control NCDs in Iran.

2 Methods

2.1 Study design & data collection

In this qualitative study, we collected data through semi-structured, in-depth and face-to-face interviews with 30 purposefully selected experts through snowball sampling, including policymakers, top managers, and relevant stakeholders, during 2018–2019 in Iran (Table 2). We continued interviews until we reached data saturation, meaning that no new theme revealed. Using the Government Healthy Food Environment Policy Index (Food-EPI) monitoring tool and complementary literature review, we developed a generic interview guide for data collection [13].

Our participants ranged from 35 to 78 years old, including 21 males and nine females. We provided all participants with an information sheet that outlined the study objectives, obtained their informed consent, and assured them about data confidentiality and anonymity. The first author (MA) conducted all interviews, except for the first interview, supervised by the corresponding author (AT). MA also attended some courses on interviewing techniques and participated in some workshops. Interviews lasted 30–90 min, 60 min on average. We took notes during the interviews and recorded the place, date, time, and other relevant matters. All interviews were digitally recorded after permission for recording from participants, transcribed verbatim, and thematically analyzed using the health policy triangle framework. The policy analysis triangle encompasses four key components: the context (the reasons behind the policy's necessity), the content (the main focus of the policy), the process (how the policy was introduced and executed), and the actors (those involved in and influencing the policy's development and implementation) [13].

To establish a constructive relationship with interviewees and enhance the rigor of study, we assessed the interviewees' knowledge of research and the interview process through the following steps:

First, during the recruitment phase, we provided detailed information about the purpose and objectives of study to potential interviewees. This allowed them to understand the research context and make an informed decision about participation.

Second, before conducting each interview, we sent out an introductory email to the participant, described the research process, explained the interview format, and addressed their potential questions or concerns. We ensured that the interviewees were aware of their rights as participants and emphasized the voluntary nature of their involvement.

During the interviews, we further assessed the interviewees' knowledge by incorporating probing questions related to their understanding of the research topic, their experiences, and their familiarity with the interview process. This allowed us to gauge their level of engagement and comprehension, ensuring that they were actively contributing to the study.

Moreover, We kept communication open and transparent throughout the research process. We encouraged the interview participants to share their feedback, ideas, and recommendations about the study. This helped build a collaborative relationship and ensured the participants were actively involved in the research.

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the participants.

2.2 Data analysis

We used a mixed deductive and inductive approach to analyze qualitative data, facilitated by the MAXQDA 11 softwareFootnote 1 (VERBI software, Germany). We analyzed the data in the following five stages, i.e., familiarization, identifying the thematic framework, indexing, mapping, and interpretation. Initially, we conducted open coding, followed by categorizing the codes into several groups and comparing them. We changed the codes constantly to show the message of the interviews and provided some participants with the transcripts, categories, subcategories, and codes to increase their credibility and sought their final approval. We sought the expertise of other researchers who were knowledgeable in qualitative research analysis to review some interviews, codes, and themes in order to ensure their validity.

2.3 Ethical clearance

The Ethical Committee of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS) approved this study (the ethical code: IR.TUMS.REC.1397.193).

3 Results

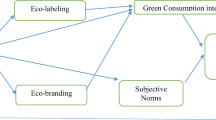

We developed five primary themes and several diet recommendations for different stakeholders, including promoting healthy symbols and supporting food products with them, food basket reforms, food labeling reforms, cooperation with other sectors, updating dietary standards and improving mechanisms to report violations of harmful products, organizing restaurants and processed foods, NCD alliance and using influential figures. In case of discrepancy, we conducted member checking. It involved sharing the identified themes with the participants themselves to validate the accuracy and relevance of the findings. Our main findings are summarized in Fig. 1.

3.1 Promoting healthy symbols and cooperation with other sectors

Designing specific symbols for healthier food products with low sugar, salt and fat was recommended as an excellent incentive to promote healthy food consumption:

“People care about two things: their income and their name. The MoHME should introduce and support every institution and organization that produces healthy products through specific symbols. Producers that provide food in accordance with the MoHME standards, need to be recognized and incentivized” (No8)

Besides, the national TV and radio (IRIB) could facilitate free advertisement of healthy food products by endorsing healthy symbols, so consumers will be encouraged to reduce the use of unhealthy products:

“One intervention is to give a safety symbol to healthy products. We have an FDO logo. Besides, we have a healthy apple symbol for some products, which differs from the FDO logo on all food products, including harmful ones. A product can receive a healthy apple symbol apart from the FDO logo. We need to promote products with the healthy apple symbol.” (No 29)

As the primary authority for public health, the MoHME is responsible for signing memoranda with other relevant ministries and organizations to enhance intersectoral collaboration and promote cooperation in health:

"Currently, there exist certain memoranda; however, they are incomplete and lack enforceability. Furthermore, certain organizations lack such agreements. " (NO18)

Our interviewees were cognizant of multisectoral cooperation significance and its impact on promoting a healthy diet:

"Working with various sectors necessitates the application of health diplomacy. To this end, the MoHME should optimally leverage the potential of media, cinema, social networks, and other relevant organizations". (No27).

3.2 Traffic light food labeling and food basket reforms

Traffic light labeling for food products became mandatory in 2005 in Iran and has become a necessary norm in the past few years. Nonetheless, some updates are necessary to enhance the impacts of such reform, i.e., making the signs larger and more readable:

“The food industry must make the food labeling legible and visible on the products.” (No1)

The problem is even worse on small-size products, where the food labeling is almost invisible. Our interviewees advised the food industry to use some attachments to make food labeling more prominent or utilize advanced technology and mobile applications:

"Sometimes the product is very small. Factories can attach a piece of paper and label it." (No12)

One policymaker added:

“We need to utilize technology more appropriately. Australia has developed software that reads product barcodes and displays product information on mobile. In fact, along with the color code, you will be able to get all the nutrition information via your mobile phone. “(No26)

Some experts accused the current traffic light food labeling of being confusing and asked for more simplification to make it more understandable:

"Labeling should be based on the type of product. It needs a fundamental change. If they offered a result, it would be much better. For example, a man's body has different colors, and his whole body turns red from very harmful products." (No4)

Another interviewee also mentioned:

"Traffic light is an educational tool. We should teach people about its mechanism, and the industry is expected to implement it appropriately to achieve desirable results. The current situation confuses the customer and should be upgraded to a better method. For example, despite its possible harms, all sections are green in zero soda and red in the dough (yogurt drink), which might have some nutritional benefits. This is misleading!" (No13)

A number of experts hold the view that the food basket requires a revision based on local and regional factors. The nutritional requirements of each region should be defined, where possible, by taking into account the availability of food resources:

"The food basket can be revised based on the unique circumstances of the country and different regions, placing greater emphasis on the consumption of vegetables and fruits." (No.27)

3.3 Updating standards and improving mechanisms to report violations in harmful products

Many interviewees called for standard revision as an essential intervention to improve the monitoring of food quality and combat the increasing trend of unhealthy food consumption:

"In harmful products, monitoring is not easy, but it is enforceable. Salt, sugar and fat standards must be defined and revised and monitored." (No27)

Some experts called upon the need to reform the monitoring mechanisms for harmful products, so products that violate the law should be introduced to the authorities:

"We should report every violation, like what the environmental health authorities do. Medical universities are required to record any violations in law and report them to the judiciary for further action and possible penalties" (No2)

Meanwhile, some experts pointed out that a long list of harmful goods might cause resistance from the industry. Therefore, they called to prepare a shortlist first of harmful goods, implement it and then move on to other goods:

"In harmful goods, we can prepare a shortlist and implement it in the industry. Then, we can add more harmful products based on the evidence. " (No19)

3.4 Organizing restaurants and processed food

One measure to encourage restaurants to use healthy foods with less sugar, salt, and fat is regular monitoring and ranking them according to health criteria:

"A while ago, something happened to the ranking of restaurants, similar to health-promoting schools. It can be helpful if we rank and value them and give them a label. Ranking restaurants based on the nutritional quality of foods in terms of sugar, salt, and fat can be other incentives." (No13)

Another interviewee noted:

"There is a trendy magazine in Germany which ranks food and prices. It makes the food industry try to improve its products. We attempted to do the same in Iran, nevertheless, the food laboratories did not cooperate. "(No12)

There are several ways to support healthy restaurants, i.e., the MoHME approval, tax exemptions, and subsidies for some products:

“One gap that I see is the incentive policies for restaurants. I think the MoHME needs to support restaurants that add calories to their menu and use low-fat oil and low-fat cheese” (No18)

Due to lifestyle changes and industrialization, people tend to use more canned and processed foods. Some interviewees pointed out that besides bread, cheese, buttermilk, and restaurants, the MoHME should also work to reduce the consumption of canned and processed foods:

“Foods such as sunflower seeds and other products also have salt and need to be paid attention to, including effective policies on canned and processed foods.” (No 27)

3.5 NGOs alliance and using influential figures

Some interviewees proposed forming an alliance of NGOs to enhance and coordinate the participation of NGOs in health and nutrition and increase the effectiveness of their activities. Currently, there are 250 NGOs active in the NCDs and 700 working in health. Their potential capacity needs to be used to convey messages related to a healthy diet through their channels:

“There are many models of people’s participation. Establishing the NCD Alliance is a practical example in our country. If the NGOs come together, they will be more effective.” (No10)

Further, the MoHME can enlist the support of influential figures, such as artists, athletes, journalists, media, and educators, to promote healthy nutrition concepts within the community:

Nowadays, many people are involved with the media, and actors, TV hosts, athletes, and celebrities significantly influence the public. Their potential can be utilized for positive purposes. (No30)

4 Discussion

This paper provides a dietary policy package for the health sector in Iran. We developed several dietary recommendations for different stakeholders, including traffic light labeling reforms, cooperation with other sectors, promoting healthy symbols, food basket reforms, updating dietary standards, adopting appropriate mechanisms to report violations of harmful product laws, scaling up mechanisms to monitor restaurants and processed foods, creating an environment for ranking restaurants and other relevant places to support a healthy diet, NGOs alliance and using influential figures.

Studies in Finland and Brazil have documented several benefits of traffic light food labeling [20]. Although implementing the traffic light food labeling policy is beneficial in Iran, it is not comprehensive and needs to be reviewed and upgraded. For example, the small size of labels and their invisibility require labels to enlarge and become readable. In line with our findings, another Iranian study also highlighted the downside of small food traffic light labels, which made it hard to decide to select products with a red symbol [21]. We recommend that the food industry use attachments, appropriate technology, and mobile applications to make comparing food products easier and avoid confusion in decision-making. A similar study recommends applying digital technology to help consumers purchase healthier products [22]. Another study shows that interpreting labels depends on health literacy, and different labeling systems may confuse consumers [23]. A similar study revealed consumers’ preference for simple labels (traffic lights) to interpret and decide easily [24]. The primary barrier to implementing a food labeling intervention in Iran is the limited public knowledge about its practical benefits. As a result, there is a pressing need to enhance the general population's knowledge through mass media campaigns and education initiatives [25, 26]. In addition to labeling, Finland has used other symptoms, such as “healthy heart,” to introduce healthy foods and help customers make better choices [27]. Therefore, applying some reforms to traffic light food labeling is the first recommendation. Further, dietary choices are based on socio-economic status, and disparities in food selection among socio-economic groups result in variations in nutrient intake [28]. Food availability, accessibility, and affordability may vary across regions, resulting in a higher difficulty in accessing certain types of foods in disadvantaged areas [29]. Therefore, we advocate revisions to the food basket based on local and regional factors.

Promoting safety symbols such as healthy apples for food products with low sugar, salt and fat is a reasonable incentive to encourage the food industry towards healthy production. For instance, in Singapore, a specific symbol indicating lower fat, sodium, and sugar in the product is used for packaged foods to promote healthy living [30]. Another study in Canada found that menu labeling with symbols significantly increased the purchasing of healthy choices [31]. Besides, the current inter-sectoral collaboration initiatives in Iran seems insufficient to ensure the effective management of NCDs [32]. A study in Iran revealed that many organizations do not consider health when making decisions [18]. As a result, the MoHME needs to sign memoranda with other sectors to enhance intersectoral collaboration and promote a healthy diet in Iran. An effective strategy for the prevention and control of NCDs requires the collaboration of all sectors to minimize NCD-related risks and alleviate their burden on communities, including: healthcare, economics, diplomacy, education, agriculture, insurance, markets, taxation, the food industry, and legislative systems [32].

Improving dietary standards is another important intervention, including the need for FDO to revise the traffic light standards [17], as well as through enforcement. Another study also called upon the FDO to revise the standards of food products and update the amount of fat, sugar, and salt content based on the new recommendations [17]. Moreover, restaurants, fast foods, and non-industrial foods need to implement robust policies regarding materials, types of food products, and consumption. Restaurant meals have more calories, carbohydrates and fats than homemade foods [33]. Ranking restaurants based on providing healthy foods with less sugar, salt, and fat and promoting healthier places by the MoHME are also important. In Oman, the Healthy Restaurants Initiative has led some restaurants to voluntarily offer healthy food recipes with low salt, fat, and sugar on their menus, while healthy food preparation classes are also offered to the staff [34]. One study found that educating restaurant owners and chefs about sodium intake can affect their behavior and food preparation [35]. A similar study in South Korea called for implementing appropriate interventions to reduce the unhealthy content of foods prepared in restaurants [36]. The implementation of calorie labeling in the study resulted in a 25-cal decrease in Taco Bell meals purchased, as observed two years later [37].

NGOs involvement is a strategy to increase the participation of NGOs in health and nutrition. As the backbone of civil society, NGOs are among the most effective and important tools available to address global issues like the environment, peace, and poverty [38]. The estimated number of NGOs in Iran was approximately 20,000 in 2020. Since their inception, NGOs in Iran have played a significant role in various aspects of healthcare, including service provision, treatment and pharmaceutical activities, financial aid, education and prevention, social well-being, advisory functions, technical information, and monitoring access to healthcare within communities [39]. NGOs increase the effectiveness of their actions. Multilateral actors emphasized the need for more public–private partnerships (PPPs) with NGOs to mobilize resources to address NCDs in an environment of economic challenges that impact aid flows [40]. Another study pointed to the critical role of NGOs in tobacco cessation interventions and ways they can help the government implement tobacco strategies [41]. Therefore, we recommend meaningful engagement with NGOs to establish a functioning alliance in health and nutrition, aiming to increase the effectiveness of activities for the NCDs program. Besides, celebrities can stimulate herd behavior and differentiate between endorsed products and their competitors. Studies in marketing have shown that celebrities' characteristics are transferred to the products they endorse, which enhances the credibility of these products. Celebrities have the potential to be an underutilized resource for public health promotion, as their influence can bring about favorable changes in public opinion and health-related behaviors [42]. Therefore, the MoHME can use celebrities' support to promote healthy nutrition in the community.

4.1 Rigor of study

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first of its type and presents a policy package for the health sector to promote a healthy diet in Iran. Four interviewees did not participate in our study due to a lack of interest or relevance, time constraints, and fear of repercussions. Nonetheless, the in-depth interviews with other stakeholders allowed us to access a reliable data source. Besides, we conducted this study before the COVID-19 pandemic. We suppose different factors might have changed people's diet, including economic conditions and food accessibility, especially among vulnerable citizens.

5 Conclusions

The Iranian health sector has developed a practical roadmap for preventing and controlling NCDs and promoting healthy nutrition. Nevertheless, the MoHME and other vital sectors need to provide a series of interventions to change people’s behavior regarding food choices to consume less unhealthy food, i.e., reforms in traffic light labeling, promoting healthy symbols, updating dietary standards and improving mechanisms to report violations in harmful products, more effective monitoring of restaurants and processed foods and NGOs alliance. Along the sustainable development goal (SDG) 3.4 pathway to reduce premature mortality due to NCDs by 30% by 2030 in Iran, we advocate evidence-informed intervention to reduce unhealthy food consumption.

Data availability

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request to interested researchers.

Notes

References

Paulson KR, Kamath AM, Alam T, Bienhoff K, Abady GG, Abbas J, et al. Global, regional, and national progress towards sustainable development goal 3.2 for neonatal and child health: all-cause and cause-specific mortality findings from the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. 2021;398(10303):870–905.

Lisy K, Campbell JM, Tufanaru C, Moola S, Lockwood C. The prevalence of disability among people with cancer, cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory disease and/or diabetes: a systematic review. JBI Evid Implement. 2018;16(3):154–66.

Murray CJ, Aravkin AY, Zheng P, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi-Kangevari M, et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. The Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1223–49.

Allen L, Williams J, Townsend N, Mikkelsen B, Roberts N, Foster C, et al. Socioeconomic status and non-communicable disease behavioural risk factors in low-income and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(3):e277–89.

Sithey G, Li M, Thow AM. Strengthening non-communicable disease policy with lessons from Bhutan: linking gross national happiness and health policy action. J Public Health Policy. 2018;39(3):327–42.

Schulze F, Gao X, Virzonis D, Damiati S, Schneider MR, Kodzius R. Air quality effects on human health and approaches for its assessment through microfluidic chips. Genes. 2017;8(10):244.

Afshin A, Sur PJ, Fay KA, Cornaby L, Ferrara G, Salama JS, et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. The Lancet. 2019;393(10184):1958–72.

Chandran A, Selva Kumar S, Hairi NN, Low WY, Mustapha FI. Non-communicable disease surveillance in Malaysia: an overview of existing systems and priorities going forward. Front Public Health. 2021;9:913.

Ahmadi A, Shirani M, Khaledifar A, Hashemzadeh M, Solati K, Kheiri S, et al. Non-communicable diseases in the southwest of Iran: profile and baseline data from the Shahrekord PERSIAN Cohort Study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–14.

Doshmangir L, Bazyar M, Majdzadeh R, Takian A. So near, so far: four decades of health policy reforms in Iran, achievements and challenges. Arch Iran Med. 2019;22(10):592–605.

Azadnajafabad S, Mohammadi E, Aminorroaya A, Fattahi N, Rezaei S, Haghshenas R, et al. Non-communicable diseases’ risk factors in Iran; a review of the present status and action plans. J Diabet Metab Disord. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40200-020-00709-8.

http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool. Accessed 21 Nov 2020. GBoDSGRdotIIfHMaEIAf.

Amerzadeh M, Takian A, Pouraram H, Sari AA, Ostovar A. Policy analysis of socio-cultural determinants of salt, sugar and fat consumption in Iran. BMC nutrition. 2022;8(1):1–7.

Mohebi F, Mohajer B, Yoosefi M, Sheidaei A, Zokaei H, Damerchilu B, et al. Physical activity profile of the Iranian population: STEPS survey, 2016. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–17.

Amerzadeh M, Salavati S, Takian A, Namaki S, Asadi-Lari M, Delpisheh A, et al. Proactive agenda setting in creation and approval of national action plan for prevention and control of non-communicable diseases in Iran: the use of multiple streams model. J Diabet Metab Disord. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40200-020-00591-4.

Amerzadeh M, Takian A. Reducing sugar, fat, and salt for prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) as an adopted health policy in Iran. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2020;34:136.

Damari B, Abdollahi Z, Hajifaraji M, Rezazadeh A. Nutrition and food security policy in the Islamic Republic of Iran: situation analysis and roadmap towards 2021. EMHJ-East Mediterr Health J. 2018;24(02):177–88.

Goshtaei M, Ravaghi H, Sari AA, Abdollahi Z. Nutrition policy process challenges in Iran. Electron Phys. 2016;8(2):1865.

Goetzke BI, Spiller A. Health-improving lifestyles of organic and functional food consumers. Br Food J. 2014;116:510–26.

Wijesinha-Bettoni R, Khosravi A, Ramos AI, Sherman J, Hernandez-Garbanzo Y, Molina V, et al. A snapshot of food-based dietary guidelines implementation in selected countries. Glob Food Sec. 2021;29:100533.

Haghighian Roudsari A, Zargaran A, Milani Bonab A, Abdollah S. Consumers’ perception of nutritional traffic light in food products: a qualitative study on new nutritional policy in Iran. Nutr Food Sci Res. 2018;69.

Schneider T, Eli K, Dolan C, Ulijaszek S. Introduction: Digital food activism–food transparency one byte/bite at a time? In: Schneider T, Eli K, Dolan C, Ulijaszek S, editors. Digital food activism. Milton Park: Routledge; 2017. p. 1–24.

Madilo FK, Owusu-Kwarteng J, Kunadu AP-H, Tano-Debrah K. Self-reported use and understanding of food label information among tertiary education students in Ghana. Food Control. 2020;108:106841.

de Menezes EW, Lopes TdVC, Mazzini ER, Dan MCT, Godoy C, Giuntini EB. Application of Choices criteria in Brazil: Impact on nutrient intake and adequacy of food products in relation to compounds associated to the risk of non-transmissible chronic diseases. Food Chem. 2013;140(3):547–52.

Amerzadeh M, Takian A, Pouraram H, Akbari Sari A, Ostovar A. The health system barriers to a healthy diet in Iran. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(1): e0278280.

Rezaei S, Mahmoudi Z, Sheidaei A, Aryan Z, Mahmoudi N, Gohari K, et al. Salt intake among Iranian population: the first national report on salt intake in Iran. J Hypertens. 2018;36(12):2380–9.

Miklavec K, Hribar M, Kušar A, Pravst I. Heart images on food labels: a health claim or not? Foods. 2021;10(3):643.

Gill M, Feliciano D, Macdiarmid J, Smith P. The environmental impact of nutrition transition in three case study countries. Food Secur. 2015;7:493–504.

Sobhani SR, Babashahi M. Determinants of household food basket composition: a systematic review. Iran J Public Health. 2020;49(10):1827.

Barclay AW, Augustin LS, Brighenti F, Delport E, Henry CJ, Sievenpiper JL, et al. Dietary glycaemic index labelling: a global perspective. Nutrients. 2021;13(9):3244.

White CM, Lillico HG, Vanderlee L, Hammond D. A voluntary nutrition labeling program in restaurants: consumer awareness, use of nutrition information, and food selection. Prev Med Rep. 2016;4:474–80.

Bakhtiari A, Takian A, Majdzadeh R, Ostovar A, Afkar M, Rostamigooran N. Intersectoral collaboration in the management of non-communicable disease’s risk factors in Iran: stakeholders and social network analysis. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1669.

Cantu-Jungles TM, McCormack LA, Slaven JE, Slebodnik M, Eicher-Miller HA. A meta-analysis to determine the impact of restaurant menu labeling on calories and nutrients (ordered or consumed) in US adults. Nutrients. 2017;9(10):1088.

Mohamed N, Elfeky S, Khashoggi M, Ibrahim S, Aliahia A, Al Shatti A, et al. Community participation and empowerment in healthy cities initiative: experience from the eastern mediterranean region. J Soc Behav Commun Health. 2020;4(2):553–65.

Park S, Lee H, Seo D-i, Oh K-h, Hwang TG, Choi BY. Educating restaurant owners and cooks to lower their own sodium intake is a potential strategy for reducing the sodium contents of restaurant foods: a small-scale pilot study in South Korea. Nutr Res Pract. 2016;10(6):635–40.

Kweon S, Kim Y, Jang M-j, Kim Y, Kim K, Choi S, et al. Data resource profile: the Korea national health and nutrition examination survey (KNHANES). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(1):69–77.

Roberto CA, Petimar J. Restaurant calorie labeling and changes in consumer behavior. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(12): e2346813-e.

Asadi-Lari M, Ahmadi Teymourlouy A, Maleki M, Eslambolchi L, Afshari M. Challenges and opportunities for Iranian global health diplomacy: lessons learned from action for prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. Health Res Policy Syst. 2021;19(1):1–15.

Bidar Z, Ghasemi G. Role of NGOs in developing the right of health. Med Law J. 2020;14(52):7–26.

McPake B. The need for cost-effective and affordable responses for the global epidemic of non-communicable diseases. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(10):e1293–4.

WH Organization. Gear up to end TB: introducing the end TB strategy. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

Hoffman SJ, Mansoor Y, Natt N, Sritharan L, Belluz J, Caulfield T, et al. Celebrities’ impact on health-related knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and status outcomes: protocol for a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression analysis. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):1–13.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to all stakeholders, healthcare providers, and interviewees who participated in this study.

Funding

This research is a part of a Ph.D. thesis in health policy at TUMS, which benefited from TUMS’ financial and intellectual support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AT and MA conceived the study. AT supervised the entire evaluation phase and revised the manuscript. HP, AO, and AKS were advisors in methodology, contributing to the intellectual development of the manuscript. MA collected data and conducted primary data analysis. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. AT is the guarantor.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethical Committee of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS) approved this study (the ethical code: IR.TUMS.REC.1397.193). Our methods were conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Information sheets were provided to the interviewees, explaining the purpose of the study to them, and written consent was obtained.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

None declared.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Amerzadeh, M., Takian, A., Pouraram, H. et al. A proposed dietary policy package for the health sector in Iran. Discov Health Systems 3, 24 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44250-024-00089-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44250-024-00089-3