Abstract

In many developing countries, like Ghana, persons with disability face a lot of marginalisation and discrimination. Despite WHO’s assertion that disabled persons deserve equal access to healthcare, disparities remain. Health professionals play a pivotal role in reducing maternal mortality. Yet few studies engage professionals to understand these perceptions and how they shape service provision. This highlights the need for research investigating health professionals’ perceptions of delivering maternal healthcare to women with disabilities in Ghana. With the aid of a qualitative approach, this study explored the perceptions of healthcare professionals on disabled women who sought maternal healthcare in Ghana. Data was gathered from 25 healthcare workers, consisting of midwives and doctors. The thematic analysis uncovered two contrasting themes—positive perceptions highlighting the determination and strength of disabled women and negative perceptions shaped by cultural biases questioning the need for disabled women to become pregnant. Bridging this gap necessitates comprehensive training, patient-centred collaborative approaches, and anti-discrimination policies to establish an equitable Ghanaian healthcare system that safeguards the reproductive rights and options of pregnant and disabled women. Dedication from all stakeholders is imperative to ensure inclusiveness and fair treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Disability, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO), is characterised as the outcome of physiological, intellectual, psychological, sensory, hormonal, biological, or any mixture of these impairments that limit a person’s capacity to engage in activities regarded as “rational” in their everyday culture [1]. Persons with disabilities account for 15% of the global population [2]. Even though the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities assures people with disabilities the same degree of access to high-quality and cost-effective primary health care, which includes sexual and maternal healthcare as non-disabled individuals [3] people with disabilities remain one of the most disadvantaged and socially marginalised groups in many countries, and Ghana is without exception [4, 5]. In Ghana, recent estimations have shown that about 8% of the country’s population has experienced some form of disability across different geographic and socio-economic groups [6]. However, among women aged 15–49 in Ghana, approximately 10.2% have some form of disability [7] with physical disabilities, visual impairment, and hearing impairments being the three most common types of disabilities experienced by this group in the country [1]. Committed to safeguarding the rights of persons with disabilities, Ghana is a signatory to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Pursuant to this commitment, the country passed the Persons with Disability Act (Act 715) in 2006 [8]. Although a full implementation and enforcement of the Act is yet to be documented, the Act ensures that persons with disabilities have the right to access healthcare services equitably as those available to the general population [8]. This means that persons with disabilities have equal access to the same or specialised range of healthcare services to achieve equality in quality and standards. The Act extends these rights to various areas, including sexual and reproductive health [8].

Nonetheless, the challenges of Persons with disabilities extend to several domains. For instance, research has shown that persons with disabilities have poor health outcomes, poor educational outcomes, reduced economic prospects, and greater chances of being poor than individuals without disabilities [9]. Notably, other studies have shown that women with disabilities are more likely to be impoverished and have worse social and economic standing than their non-disabled counterparts [5, 10]. Nonetheless, it is also well documented that women with disabilities have higher rates of medical risk factors, such as obesity, diabetes, stress, depression, smoking, and alcohol and/or substance use, which are more prevalent among the disabled in general [11,12,13]. Given the risk factors that Women With Disability introduce into pregnancy, they are likely to have a higher theoretical risk of maternal mortality [14,15,16]. Numerous explanations have been advanced for these maternal complications associated with women living with disabilities among health professionals [17, 18]. Meanwhile, health professionals are critical workers who provide primary care to individuals seeking maternal care. They play an important role in mitigating maternal health challenges by providing essential maternal health care at the household and community level, reducing inequalities in health care for marginalised populations like the poor and disabled, providing education and primary curative health services, and liaising between the community and more skilled workers and facility-based services [19, 20]. Notwithstanding these benefits, research and reports in developing countries have identified several factors contributing to maternal mortality [21]. This includes a lack of health workers, an unequal distribution of the health workforce, and a lack of motivation among health professionals [22, 23]. The above factors are still significant as they contribute significantly to maternal health complications among pregnant women and more adversely for those with disabilities [24,25,26].

In light of the recently established Sustainable Development Goals, there has been an increasing body of research in developing countries that addresses the health needs, difficulties and hindrances to maternal and reproductive healthcare care services by women with disabilities [27,28,29]. For instance, in Ghana, several studies have recently explored various disability issues, including the rights of persons with disabilities [30,31,32,33], challenges to accessing healthcare among persons with disabilities [18, 34, 35], and the recognition of the disabled in sexual and reproductive health policies [36,37,38]. However, a research gap remains regarding health professionals’ perceptions of maternal healthcare provision for women with disabilities. Given professionals’ central role, their perceptions likely influence service delivery to this vulnerable group. Yet few studies engage professionals to understand these perceptions and how they shape service provision. This highlights the need for research investigating health professionals’ perceptions of delivering maternal healthcare to women with disabilities in Ghana. As such, this research investigates health professionals’ perceptions of maternal healthcare delivery for women with disabilities. The findings will help fill a significant knowledge gap regarding health professionals’ perceptions of maternal healthcare for women with disabilities in Ghana. This can inform efforts to improve this population’s maternal health services and outcomes.

1.1 Intersectionality

In many societies, persons with disabilities face marginalisation and barriers to healthcare access [2]. However, the disadvantage intersects with gender, as disabled women experience far more significant social, economic and health challenges than disabled men [10]. This study explores healthcare professionals’ perceptions of providing maternal care to disabled women in Ghana through an intersectionality lens. Intersectionality is a theoretical framework analysing how multiple social categorisations—such as gender, race, class, and disability status—intersect at the micro level of individual experience to reflect multiple interlocking systems of privilege and oppression at the macro social-structural level [39]. The theory examines how the intersection of these categories produces compounded inequality and complex marginalisation. In Ghanaian society, both disability and female gender independently incur cultural stigma and assumptions limiting autonomy and rights. However, their intersection magnifies disabled women’s marginalisation, restricting reproductive choices far more severely than able-bodied women or disabled men [35]. Disabled women disproportionately face poverty, dependence on others, assumptions about incapacity for childrearing responsibilities, and extreme pressures against becoming pregnant [35]. These intersecting biases rooted in societal attitudes about disability and womanhood likely influence healthcare professionals as well. Providers play a crucial role in shaping access to health services for vulnerable groups [20]. Their perceptions regarding disability and gender potentially impact the maternal healthcare disabled women receive. Yet few studies engage professionals to understand these views in Ghana. This research aims to address this gap by investigating health professionals’ perceptions of delivering maternal healthcare to disabled women. The findings can inform multipronged efforts needed to transform inherently biased attitudes, practices and policies that restrict equitable, inclusive maternal healthcare access for disabled women.

2 Methods

2.1 Research design

This study employed a qualitative case study design to examine professionals’ perspectives within the context of maternal healthcare for women with disabilities. This approach was chosen based on the value of gathering and analysing highly relevant data through qualitative methodology. In-depth interviews with healthcare professionals enabled a comprehensive exploration of their nuanced views on service delivery to this population. The qualitative approach provided opportunities to delve into complex subject matter in a way that quantitative methods may only capture partially. Conducting open-ended interviews yielded detailed insights directly from professionals closest to the issue, serving as powerful instruments for understanding their experiences and beliefs. Researchers could probe important topics inaccessible via surveys or questionnaires through these interviews. Adopting a qualitative case study methodology allowed the collection of rich, descriptive data on professionals’ perceptions, capturing the complexity of their vantage points through their own words. This intensive pursuit of qualitative data from interviews was critical to obtaining the understanding needed to elucidate professionals’ perspectives on delivering care to women with disabilities. The methodology shaped the depth and specificity of inquiry, facilitating analysis of professionals’ views within the precise context of interest.

2.2 Study area

The study was conducted at the Midwifery unit at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) Hospital. The unit accommodates roughly 15 to 20 patients. Due to the limitations of the midwifery unit, the hospital has commenced the construction of an ultra-modern midwifery unit. The maternity unit delivers care to a socioeconomically diverse patient population, including many women with disabilities. Thus it provided an information-rich setting suitable for exploring health professionals’ perspectives on serving disabled pregnant women seeking maternal healthcare. Generally, the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) Hospital was established primarily to meet the healthcare needs of university employees, their dependents, and student enrollment [40]. It has now opened its doors to the general public. It is now able to provide health services to the surrounding 30 communities, which are experiencing population growth at an unprecedented rate [40]. The hospital currently serves over 200,000 people, including 21,000 students, 30,000 employees and dependents, and approximately 150,000 people from the surrounding 30 communities [40]. The University Health Services provides primary medical care as well as specialised departments such as outpatient/inpatient, radiology, laboratory, surgery, obstetrics, gynaecology, public/ occupational health, dental clinic, pharmacy, and student clinic (NHIS). The Student Clinic (SC) opened on April 2, 2007, to improve health care for university students [41]. The clinic is conveniently located on the university’s main campus [41]. The clinic has a standby emergency service ambulance, which comes with its power plant in the event of an emergency. The clinic was established to help relieve the strain on the university hospital [42]. Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology has a strategic plan to become a leading university health service provider with a broad range of general and specialised services, establishing it as a centre of excellence for quality health care, teaching, and research. The mission of the hospital is to promote and preserve the health and well-being of the university community and the surrounding 30 communities through the efficient and compassionate delivery of high-quality health care, to educate and train physicians and other health care professionals, and to ensure the continued availability of comprehensive health services for the university community and surrounding 30 communities [42].

2.3 Sample size

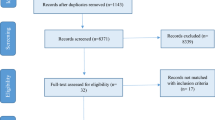

In all, 25 healthcare professionals participated in this research. Of the 25 health professionals, 20 were midwives, and 5 were doctors. 23 were females, and 2 were males. Regarding years of experience, 12 health professionals had less than 5 years’ experience. 7 health professionals had 5–10 years of experience, and 6 had more than 10 years of experience. The saturation of the data determined the above sample size, thus 25. Data saturation occurs when additional data collection fails to shed new light on the issue being investigated; saturation has been reached (Ryan and Bernard 2000). In the case of this research, data saturation occurred on the 24 participants, and was confirmed by the 25th participants. Table 1 summarizes the demographics of participants used in the study.

2.4 Sampling technique

The study used a purposive sampling technique in selecting participants for the study. Purposive sampling is a non-probability sampling method in which researchers choose a sample out of the population to participate in a research based on their judgment [43]. Essentially, purposive sampling is the deliberate selection of participants based on their ability to explain a particular theme, concept, or phenomenon [44]. Purposive sampling was the most appropriate sampling technique for this research since researchers wanted to recruit information-rich cases that could provide detailed insights about this issue central to the study purpose. In this case, it was vital to interview healthcare workers with direct professional experience caring for disabled women seeking maternal services. Specifically, recruiting midwives and doctors who have worked with this patient population enabled the collection of data rooted in real-world encounters. This purposive approach ensured that participants could provide first-hand insights about delivering obstetric care to women with disabilities based on their occupational knowledge and exposure. The purposive sampling process began when the researcher went to the maternal unit of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology hospital and got a list of midwives and physicians who work there. This list, with the criteria of (a) Either a doctor or a nurse, (b) having worked or worked with women with disabilities in the Midwifery Unit, and (c) Having more than a year of experience working with women with disabilities, were used in the selection of midwives and physicians. The researcher began interviews after these selections were made.

2.5 Sources of data

The data used for the study was gathered from primary sources by the researchers. The participants, thus, healthcare professionals, including physicians and midwives, served as the primary data source for this study.

2.6 Data collection

This study was part of a broader research project investigating healthcare professionals’ experiences providing maternal health services to women with disabilities in Ghana. As such, a semi-structured interview guide was developed to address the following specific research questions for this study: What perceptions do health professionals have towards women with disabilities seeking maternal health? What challenges do health professionals face in delivering maternal healthcare to women with disabilities? And what resources do health professionals need to provide high-quality maternal health services? Hence, the interview guide covered questions on perception, challenges, and resources health professionals have encountered regarding women with disabilities seeking maternal health. Specific questions asked during the in-depth interviews included: What perceptions do you have about disabled women becoming pregnant and seeking maternal healthcare? In your experience, what specific needs or challenges do women with disabilities have during pregnancy and childbirth?

Data collection began when the second author (EAA) and the corresponding author (EA) obtained a list of midwives and physicians working in the maternal unit of Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology Hospital and selectively recruited participants who met the inclusion criteria. The use of in-depth interviews ensured that the participants had the luxury of time, space, and flexibility to share their experiences. Furthermore, the approach allowed the researchers to probe into new insights from the participant’s responses [45]. The eligible midwives and physicians were contacted to schedule interviews regarding their perspectives on providing maternal healthcare to women with disabilities. The interviews were conducted by two authors, the second author (EAA) and the corresponding author (EA), who are both well-versed in collecting qualitative data. Interviews lasting 30–60 min were conducted in a private room at the hospital using an interview guide approach to explore relevant topics in depth while still allowing conversational flow. With permission, interviews were audio recorded and supplemented by handwritten notes. Recruitment and interviews continued until data saturation was attained, that is, no substantively new themes emerged from additional interviews. Verbatim transcriptions were created from the recordings and verified for accuracy. The purposive selection of knowledgeable informants and in-depth, conversational interview structure allowed for a nuanced investigation of the research objectives.

2.7 Data analysis

Data analysis began when the first author (EAA) transcribed the audio recordings verbatim to create written transcripts of the interviews. The transcripts were then verified against the original audio recordings by the corresponding author (EA) to confirm accuracy before data analysis began. Thematic analysis was used to analyse the qualitative data while centering the respondents as the focus of the study. This enabled a deeper examination of the phenomenon beyond simple theme identification to gain a comprehensive understanding [46]. Braun and Clark [46] six phases for conducting thematic analysis guided the analytic process. The process involves becoming acquainted with the data, programming, identifying, evaluating, defining, and labelling patterns and documenting the findings. The research questions of the study were analysed using these stages.

Thematic analysis of this study began with the familiarisation of data. Familiarisation involves active and repeated reading of the entire data set by the researcher to be conversant with the data [46]. With this, the all researchers read through all field transcripts to be familiar with that data. This offered a valuable outlook on the raw data and was a prerequisite for all subsequent stages. The second stage, coding, entails the researcher developing a phrase to represent a fundamental segment, or element, of raw data or information that can be evaluated meaningfully in relation to the phenomenon [46]. So, for instance, extracts such as “It’s amazing how strong some of these disabled are. When I say strong, I don’t mean in the physical aspect. I mean strong in spirit. Against all odds, which is the problem with their disability, they can overcome and give birth”. This was also given the code of strength and confidence. The next stage, which is stage 3, is searching for themes. This stage involves examining the coded and collated data extracts to look for potential themes of broader significance [46]. So, codes such as strength and confidence were given the theme of positive perception. In the next stage, stage 4, additional codes from different transcripts were added to the theme of positive perception. This stage ensures that all codes have been added to a particular theme. In stage 5, the researcher creates a definition and narrative description of each theme and explains why it is relevant to the larger research question [46]. All researchers defined each theme and provided a narrative description explaining the theme’s essence to the larger research. For instance, the theme of positive perception and its relevance to the research questions were explained among the authors. The sixth and final stage entails writing the final analysis and description of the findings [46]. The researcher (EA) wrote a final analysis with the themes that emerged from the data obtained from the field.

2.8 Ethical consideration

The ethical considerations that needed to be followed were informed consent and voluntary participation. Other considerations included ensuring that participants were not harmed, maintaining the confidentiality of the data collected, and protecting the privileges of participants. The research protocol for this study involving human participants was reviewed and approved by the College of Humanities Ethics Committee of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST). All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards set by the College of Humanities Ethics Committee of KNUST and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Further, each health professional invited to participate received detailed information about the study’s purposes and procedures so they could decide whether to take part. They were informed of the voluntary nature of participation and the option to decline participation or opt-out at any time. Signed consent was gathered from every interviewee prior to conducting interviews. Further, the confidentiality of participants was paramount. The researchers ensured that no personally identifying information was collected or attached to interview data. Pseudonyms were assigned for any illustrative quotes or excerpts used from the interviews. Transcripts, notes, recordings and other data collection artefacts presented no participant names, positions, or other direct identifiers. Researchers were also committed to non-maleficence—ensuring no harm would come to participants due to the study. By guaranteeing confidentiality and anonymity in data reporting, professionals could share perceptions freely without concern over professional repercussions for their viewpoints. Interviews were scheduled privately during participants’ work shifts to avoid taking additional personal time. Each participant was treated professionally and allowed to clarify any interview remarks as desired. Finally, fidelity and transparency were upheld as researchers accurately conveyed the voluntary nature, aims, methods and intended uses of data to any participants. Interviewers remained open to questions, ensuring subjects were fully informed throughout the process. The researchers adhered closely to the methods and procedures outlined in the approved protocols by the university ethics review committee. Upholding these ethical obligations throughout the qualitative study allowed robust data collection while protecting the professional participants’ dignity, autonomy and interests.

3 Findings

To fully understand the maternal healthcare delivery of women with disabilities, it was imperative to investigate the perception of healthcare professionals towards women with disabilities seeking maternal healthcare. From the data gathered, two themes emerged from the findings. These were positive perceptions and negative perceptions.

3.1 Positive perception

The data revealed that some health professionals had positive perceptions towards women with a disability seeking maternal health care. According to the participants, although they were fully aware of the stresses that come with pregnancy, they were overwhelmed by the zeal and determination that some disabled women wielded, which allowed them to go through pregnancy and childbirth regardless of the stresses that come with it, and particularly for them having disabilities. As a result, they are mostly left in awe and admiration of the strength and confidence on the part of these disabled, pregnant women seeking maternal health care.

For instance, to HP 4, she had this to share about how she perceives pregnant, disabled women seeking maternal healthcare. This is how she puts it;

“…Even for the abled, when they are pregnant, I see the stress they go through, and so when I see those people, I feel like that’s a double load of stress on them. And then sometimes, you see some of them and see confidence, you see strength, and you see them exuding so much confidence that you feel that if she can do it, you can also do it. It’s not like seeing her as less of a human because she is disabled, but you think she’s still here even with all she has been through. Sometimes I feel compassionate, and other times even though I feel compassionate, I see strength.”

The above extract reveals how HP4 feels compassionate for disabled women seeking maternal care. HP5 also had this to say on the perception of confidence;

‘It’s amazing how strong some of these disabled are. When I say strong, I don’t mean in the physical aspect. I mean strong in spirit. Against all odds, which is the problem with their disability, they can overcome and give birth. I see strength and confidence. Because even though I am an abled woman, I am scared of pregnancy. They are very strong”.

In addition to strength and confidence, some participants indicated that if the disability does not affect the reproductive system, they do not see why a disabled woman should not give birth. According to these participants, just like abled women, disabled women have a reproductive system. Hence, they should give birth. HP 6 had this to say about this;

“My perception of them is dependent on the type of disability. I say this because it depends on which body part is affected by the disability. Having a disability in the leg does not affect a woman’s chances of giving birth. Suppose the disability doesn’t allow the person to give birth or gives them a lower chance of giving birth. In that case, the doctor of such a person should advise the lady because there might be a risk, but if it doesn’t affect the pregnancy in any way, then there is a possibility to give birth if she wishes to give birth”.

From the extracts, some disabilities don’t affect pregnancy, but others may pose risks, so doctors should advise accordingly about each woman’s situation. Just like HP6, HP1 had similar thing to say;

“If the woman doesn’t have a disability in relation to the reproductive organ, it shouldn’t be a big concern. She can get pregnant and deliver. If she has assistance and the strength to go through pregnancy and push when it is time, I see no problem. But if the disability is related to the reproductive system, other procedures can be done. She can try artificial insemination or surrogacy to have a child if she needs one. She doesn’t necessarily have to carry her child herself”.

The above quotes indicate that unless reproductive organs are affected, disability need not bar pregnancy. Even if it does, assistance and alternative procedures like surrogacy can enable motherhood. In addition to HP6 and HP1, HP12 added this to the discussion on reproductive organs.

“I would say that per the knowledge doctors and midwives have now, I wouldn’t discourage anyone with a disability from giving birth because we have many solutions to some problems that they have. Because of the woman I spoke about, if it weren’t that she went for antenatal clinic at maternity care and came to the hospital, no doctor would have encouraged her to go in for vaginal delivery, they would have booked her for Ceasearian Section, and everything would be ok, and her baby would have been alive. But it’s because she went to the maternity care, and I don’t know the kind of care they are giving there because someone with a limping gate as a midwife should come to mind that the person won’t have an adequate pelvic. So, people like that are not encouraged to deliver by themselves. So, I think it’s because of the places they go for maternity services. However, being disabled does not mean you can’t give birth”.

From the above extracts, it is evident that some health professionals did not see any reason why women with disabilities should not be encouraged and motivated to give birth and also have babies as every other woman would be.

3.2 Negative perception

While some health professionals had positive perceptions towards pregnant women who sought maternal health care, others had negative perceptions. To these participants, so far as one is disabled, it was very problematic and unnecessary for disabled women to get pregnant and maintain it regardless of the type of disability.

For instance, HP20 had to say this when asked about her perceptions about disabled pregnant women seeking maternal healthcare. She opines that;

“Even for the abled, pregnancy presents several challenges. Pregnancy is a lot of work on its own. Taking into consideration the nine-month journey, labour and delivery. It is a complete work. Pregnancy is difficult for able-bodied women, but much more so for the disabled. So, I wonder why disabled women get pregnant since they need a lot of help during their pregnancy.”

Pregnancy’s physical and emotional challenges are multiplied for disabled women, who require extra help, so their desire for motherhood despite difficulties is remarkable. More similarly, HP19 indicated that she sees it as a burden when the disabled is pregnant; she had this to say;

“Sometimes you feel it’s a burden for that person. I once fell sick and had a leg problem and needed to be assisted all the time. It made me so uncomfortable. So, to be in that state is not an easy thing because you have to depend on people. After all, you are disabled in your leg and can’t walk or do anything. Even when you want to ease yourself, you must be assisted with the chamber pot. There are a lot of pregnancy complications. Don’t see why they should get pregnant”.

In addition, HP 2 also indicated that she does not see disabled pregnant women as having the ability to have and maintain a pregnancy, given the stress that comes with it. She puts it like this;

“I do not see them as having what it takes to be pregnant in the first place, even to think of it. Once pregnant and they come here, they burden the professionals here. Something that could have been prevented if they had chosen not to become pregnant in the first place. So, personally, I don’t think disabled women should be pregnant because of the burden it brings on us working here. They can adopt children, but to give birth is a big issue for me.”...

Also, some participants indicated that they had a negative perception when disabled pregnant women had more than one child. HP16 put it in the following;

“The first thing that came to mind when I saw the woman was retro positive, and she had her B twin, and it was her third pregnancy. So, as soon as I saw her and read about her, I asked myself, “Why didn’t she take a break for a while?” and “Why did she have to be pregnant for the third time knowing her condition and the number of babies she had?” She should be more concerned about her health because this was her third pregnancy. Given their medical situation, I believe she could have avoided the pregnancy at the very least”.

In a somewhat similar fashion to HP16, HP7 also indicated that pregnancy worsens the health conditions of disabled pregnant women, as such, there was no need to be pregnant. This is how she puts it;

“Most of these pregnant women are inactive already because of their condition, and the pregnancy worsens. When it happens that way, the burden they bring to us when they come for maternity is too much. I wonder why a disabled person would worry themselves to even get pregnant in the first place. Pregnancy is not for the disabled but for the abled. Even abled pregnant women are crying, let alone disabled pregnant women”.

Moreover, according to HP3, she sees it as very worrying for a disabled woman to get pregnant. She puts her views across like this;

“I see them to be worrying themselves too much. Already, you’re undergoing the stress and challenges that come with being a disabled person. Only for you to add to this stress to the pregnancy. I think they do not think about their welfare because if they do, no disabled person would want to get pregnant and keep it. What if the unborn also becomes disabled after birth? You see the thing. So, in my own opinion, advising disabled women to get pregnant and give birth would be the last thing I’ll think of or do. They can go ahead and have sex, even that one there is a question mark, but to give birth, it’s a no-go area for me”.

From the quotations above, it is evident that some healthcare professionals perceived disability as a burden. Hence, being a disabled woman, there is no need to get pregnant to avoid pregnancy stress and also avoid being overburdened given their conditions.

4 Discussions

Our current study has found that healthcare professionals had positive and negative perceptions about disabled pregnant women seeking maternal healthcare services. Regarding positive perception, the findings reveal that some healthcare professionals perceive disabled, pregnant women seeking maternal care as strong, confident and courageous for pursuing motherhood despite disability-related challenges. This positive viewpoint aligns with research indicating that some disabled women reject disability as a barrier to childbearing and approach pregnancy with self-empowerment [47]. When disabled women present themselves as capable and determined, they appear to gain health professionals’ admiration and respect, leading to ablest assumptions [10]. Health professionals view these women as equally deserving of quality care as non-disabled mothers [48]. However, maintaining these positive perceptions requires continuously educating disabled pregnant women to reinforce norms of appearing “strong” and “capable” when seeking care [49]. The findings suggest that positive health professional attitudes rest on presumptions of able-bodiedness and resilience and not necessarily the recognition of disabled women’s autonomy and rights [50]. This demonstrates how the intersection of social categorisations—such as gender and disability status—intersect within the context of maternal healthcare provision to disabled pregnant women to reflect multiple interlocking systems of privilege and treatment options. Being a woman in itself and having a disability in Ghana independently incur cultural stigma and assumptions that limit autonomy and rights. The intersection of these social categorisations magnifies disabled women’s marginalisation and restricts their reproductive choices comparatively to abled persons [35]. Therefore, such perceptions among healthcare professionals do not align with international standards that promote the rights and autonomy of disabled pregnant women, irrespective of their abilities [51]. This underscores the need to alter these positive perceptions among healthcare professionals to be rooted in an understanding and acknowledgement of disabled women’s rights and autonomy. Recognising disabled pregnant women’s rights and autonomy in decisions related to their reproductive health will help to strengthen maternal healthcare systems that are inclusive and responsive to the specific needs of women, particularly those with disabilities. Further, our study findings revealed that aside from the positive perceptions, some healthcare professionals delivering maternal healthcare services to disabled pregnant women had negative perceptions about disability. According to the findings, healthcare professionals held the perception that being disabled in itself made it unnecessary for disabled women to have or think about having children, especially given the complications that come with pregnancy and childbirth, even for non-disabled women. This finding is not surprising given how individuals have been shaped to view disability through sociocultural practises and belief systems in Ghanaian society. The presence of stigmatisation reflects the influence of dominant cultural beliefs and societal norms in Ghana that have traditionally shaped how disability is regarded. Through socialisation, these cultural and religious belief systems significantly affect public attitudes and assumptions about disabled and disabled individuals [52]. These belief systems foster adverse societal attitudes and treatment of the disabled, particularly disabled women, as documented by studies across contexts [53, 54]. For healthcare professionals, internalising such cultural biases through socialisation can translate into discriminatory actions and insensitivity towards pregnant, disabled women and their maternal health needs, as several studies highlight [55,56,57]. An appropriate approach recognises that these mixed perceptions (positive and negative) stem from providers’ cultural conditioning. Those expressing more progressive views have likely been exposed to recent advocacy efforts empowering disabled Ghanaians. However, negative perceptions remain shaped by inherited assumptions. Bridging this gap requires expanded training on disability rights and competencies. Educational programs can raise awareness of the needs and experiences of pregnant patients with disabilities, helping providers recognise and challenge inherent biases shaped by cultural beliefs. Developing this understanding is critical to dismantling prejudicial attitudes. Second, facilities should adopt collaborative care approaches that actively involve disabled women in decision-making about their maternal healthcare. Giving patients a voice and agency is essential for patient-centred care. Through open, non-judgmental communication, providers can better understand women’s preferences and empower them to make informed reproductive choices. Finally, policy and institutional reforms must reinforce training and collaborative care with robust protections against discrimination. Laws and policies should uphold disabled women’s equal rights to healthcare and mandate accessibility accommodations. With multifaceted efforts to transform perceptions, practices and structures, Ghana’s healthcare system can overcome inherited cultural assumptions and ensure dignified, equitable care for all women seeking maternal services—regardless of disability. However, change requires sustained commitment, dialogue and advocacy. By working together, providers and patients can make healthcare more inclusive and responsive to the needs of disabled pregnant women.

5 Conclusions

This study reveals the multifaceted perceptions held by healthcare professionals towards disabled women seeking maternal care in Ghana. The findings underscore the coexistence of positive and negative perceptions, reflecting the influence of cultural conditioning on health professionals. Some professionals perceive disabled, pregnant women through an empowering perspective—as courageous, resilient individuals meriting respect for pursuing motherhood notwithstanding disability. However, these ostensibly positive perceptions frequently rely on ableist assumptions regarding appearances of “strength” that disregard disabled women’s autonomy. Conversely, other professionals had negative perceptions enmeshed in sociocultural stigma that questioned the very capacity of disabled women to be mothers. As demonstrated, such biases can propagate discrimination and insufficient maternal healthcare provision. Bridging this divide requires multifaceted efforts to transform perceptions, practices and policies. Comprehensive training and education are needed to help professionals recognise and challenge inherent cultural biases. Patient-centred collaborative approaches that amplify disabled women’s voices are essential for equitable care. Robust anti-discrimination protections and reforms must reinforce inclusion. Existing policies and health frameworks such as the Disability Act of Ghana (Act 751), the National Health Policy of Ghana, the “Code of Patients’ Rights” developed by the Ghana Health Service, and international guidelines such as the World Health Organisation’s recommendation on health promotion interventions for maternal and newborn health could be drawn on to promote the rights and access to maternal care for all women, especially those with disabilities. With concerted collaboration, Ghana’s healthcare system can progress towards more empowering, equitable care that upholds all women’s reproductive rights and choices. However, driving positive change requires sustained commitment from all stakeholders to make Ghana’s healthcare settings more welcoming for disabled pregnant women.

Data availability

All data analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

WHO, ‘World Report on Disability’. Accessed: Nov. 04, 2022. Available: https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/sensory-functions-disability-and-rehabilitation/world-report-on-disability.

Krahn GL. WHO world report on disability: a review. Disabil Health J. 2011;4(3):141–2.

Adams D, et al. Service use and access in young children with an intellectual disability or global developmental delay: associations with challenging behaviour. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2018;43(2):232–41. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2016.1238448.

Montez JK, Zajacova A, Hayward MD. Disparities in disability by educational attainment across US states. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(7):1101–8.

Pinilla-Roncancio M. The reality of disability: multidimensional poverty of people with disability and their families in Latin America. Disabil Health J. 2018;11(3):398–404.

Ghana Statistical Service, ‘2021 Population and Housing Census’. Accessed: Jan. 26, 2024. Available: https://census2021.statsghana.gov.gh/.

Ghana Statistical Service, ‘Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), Ghana Health Service...—Google Scholar’. Accessed: Jan. 26, 2024. Available: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?&title=Ghana%20maternal%20health%20survey%202017&publication_year=2018#d=gs_cit&t=1706270846304&u=%2Fscholar%3Fq%3Dinfo%3AXzjUxxrsKpAJ%3Ascholar.google.com%2F%26output%3Dcite%26scirp%3D0%26hl%3Den.

‘Ghana—Persons With Disability Act, 2006—Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund’. Accessed: Jan. 26, 2024. Available: https://dredf.org/legal-advocacy/international-disability-rights/international-laws/ghana-persons-with-disability-act-2006/.

Banks LM, Kuper H, Polack S. Correction: poverty and disability in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(9): e0204881.

Iezzoni LI, et al. Physicians’ perceptions of people with disability and their health care: study reports the results of a survey of physicians’ perceptions of people with disability. Health Aff. 2021;40(2):297–306. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01452.

Alhusen JL, Bloom T, Laughon K, Behan L, Hughes RB. Perceptions of barriers to effective family planning services among women with disabilities. Disabil Health J. 2021;14(3): 101055.

Kitsantas P, Aljoudi SM, Booth EJ, Kornides ML. Marijuana use among women of reproductive age with disabilities. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61(4):554–62.

Matin BK, Williamson HJ, Karyani AK, Rezaei S, Soofi M, Soltani S. Barriers in access to healthcare for women with disabilities: a systematic review in qualitative studies. BMC Women’s Health. 2021;21(1):1–23.

Dissanayake MV, Darney BG, Caughey AB, Horner-Johnson W. Miscarriage occurrence and prevention efforts by disability status and type in the United States. J Women’s Health. 2020;29(3):345–52.

Mitra M, Smith LD, Smeltzer SC, Long-Bellil LM, Sammet Moring N, Iezzoni LI. Barriers to providing maternity care to women with physical disabilities: perspectives from health care practitioners. Disabil Health J. 2017;10(3):445–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2016.12.021.

Tarasoff LA, Ravindran S, Malik H, Salaeva D, Brown HK. Maternal disability and risk for pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222(1):27-e1.

Acheampong E, Nadutey A, Anokye R, Agyei-Baffour P, Edusei AK. The perception of healthcare workers of People with Disabilities presenting for care at peri-urban health facilities in Ghana. Health Soc Care Community. 2022;30(4):e944–52.

Dassah E, Aldersey HM, McColl MA, Davison C. Health care providers’ and persons with disabilities’ recommendations for improving access to primary health care services in rural northern Ghana: a qualitative study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(9): e0274163.

Laurenzi CA, et al. Instructive roles and supportive relationships: client perspectives of their engagement with community health workers in a rural South African home visiting program. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20(1):1–12.

Tuyisenge G, Crooks VA, Berry NS. Facilitating equitable community-level access to maternal health services: exploring the experiences of Rwanda’s community health workers. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):1–10.

Prodinger B, Stucki G, Coenen M, Tennant A. The measurement of functioning using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: comparing qualifier ratings with existing health status instruments. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(5):541–8.

Arisukwu O, Akinfenwa S, Igbolekwu C. Primary healthcare services and maternal mortality in Ugep. Ann Med Surg. 2021;68: 102691.

Sharona DD. A study of maternal near miss cases in department of obstetrics and gynecology, Government Mohan Kumaramangalam Medical College and Hospital, Salem. PhD Thesis, Government Mohan Kumaramangalam Medical College, Salem, 2020.

Brown HK, et al. Association of preexisting disability with severe maternal morbidity or mortality in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2034993–e2034993.

Devkota HR, Murray E, Kett M, Groce N. Healthcare provider’s attitude towards disability and experience of women with disabilities in the use of maternal healthcare service in rural Nepal. Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):79. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-017-0330-5.

Mueller BA, Crane D, Doody DR, Stuart SN, Schiff MA. Pregnancy course, infant outcomes, rehospitalization, and mortality among women with intellectual disability. Disabil Health J. 2019;12(3):452–9.

Badu E, Gyamfi N, Opoku MP, Mprah WK, Edusei AK. Enablers and barriers in accessing sexual and reproductive health services among visually impaired women in the Ashanti and Brong Ahafo regions of Ghana. Reprod Health Matters. 2018;26(54):51–60.

Ganle JK, Otupiri E, Obeng B, Edusie AK, Ankomah A, Adanu R. Challenges women with disability face in accessing and using maternal healthcare services in Ghana: a qualitative study. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(6): e0158361. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158361.

Kumi-Kyereme A. Sexual and reproductive health services utilisation amongst in-school young people with disabilities in Ghana. Afr J Disabil (Online). 2021;10:1–9.

Ayoung DA, Baada FN-A, Baayel P. Access to library services and facilities by persons with disability: insights from academic libraries in Ghana. J Librariansh Inf Sci. 2021;53(1):167–80.

Mfoafo-M’Carthy M, Grischow JD, Stocco N. Cloak of invisibility: a literature review of physical disability in Ghana. SAGE Open. 2020;10(1):2158244019900567.

Odame PK, Abane A, Amenumey EK. Campus shuttle experience and mobility concerns among students with disability in the University of Cape Coast, Ghana. Geo Geogr Environ. 2020;7(2): e00093.

Opoku MP, Nketsia W, Agyei-Okyere E, Mprah WK. Extending social protection to persons with disabilities: exploring the accessibility and the impact of the disability fund on the lives of persons with disabilities in Ghana. Global Social Policy. 2019;19(3):225–45.

Abodey E, Vanderpuye I, Mensah I, Badu E. In search of universal health coverage–highlighting the accessibility of health care to students with disabilities in Ghana: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1–12.

Naami A, Okine J. CRPD Article 6–Vulnerabilities of women with disabilities: Recommendations for the disability movement and other stakeholders in Ghana. In Disability Rights and Inclusiveness in Africa: The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Challenges and Change, Boydell & Brewer, 2022, p. 193.

Abdul Karimu ATF. Disabled persons in Ghanaian health strategies: reflections on the 2016 adolescent reproductive health policy. Reprod Health Matters. 2018;26(54):20–4.

Ganle JK, Ofori C, Dery S. Testing the effect of an integrated-intervention to promote access to sexual and reproductive healthcare and rights among women with disabilities in Ghana: a quasi-experimental study protocol. Reprod Health. 2021;18(1):1–11.

Mills AA. Navigating sexual and reproductive health issues: voices of deaf adolescents in a residential school in Ghana. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;118: 105441.

Devkota HR, Clarke A, Murray E, Kett M, Groce N. Disability caste, and intersectionality: does co-existence of disability and caste compound marginalization for women seeking maternal healthcare in Southern Nepal. Disabilities. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities1030017.

Gyapong R. Characterization of Severe Malaria and Treatment-Related Adverse Drug Reactions among Hospitalised Children, at the KNUST Hospital, Kumasi, Ghana. PhD Thesis, Citeseer, 2009. Accessed: Feb. 07, 2024. Available: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=f08c2a35cf6a74934f614409490f3313c93d897a.

Gyamfi D, et al. Prevalence of pre-hypertension and hypertension and its related risk factors among undergraduate students in a Tertiary institution, Ghana. Alexandria J Med. 2018;54(4):475–80.

Anokye R, et al. Perception of childhood anaemia among mothers in Kumasi: a quantitative approach. Ital J Pediatr. 2018;44(1):142. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-018-0588-4.

Campbell S, et al. Purposive sampling: complex or simple? Research case examples. J Res Nurs. 2020;25(8):652–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987120927206.

Etikan I, Musa SA, Alkassim RS. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am J Theor Appl Stat. 2016;5(1):1–4.

Marvasti A, Freie C. Research interviews. The BERA/SAGE handbook of educational research, pp. 624–639, 2017.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Bradbury-Jones C, Breckenridge JP, Devaney J, Kroll T, Lazenbatt A, Taylor J. Disabled women’s experiences of accessing and utilising maternity services when they are affected by domestic abuse: a critical incident technique study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15(1):181. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0616-y.

Smeltzer SC, Wint AJ, Ecker JL, Iezzoni LI. Labor, delivery, and anesthesia experiences of women with physical disability. Birth. 2017;44(4):315–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12296.

Dudgeon MR, Inhorn MC. Men’s influences on women’s reproductive health: medical anthropological perspectives. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(7):1379–95.

Kallianes V, Rubenfeld P. Disabled women and reproductive rights. Disability Soc. 1997;12(2):203–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599727335.

World Health Organization, WHO Recommendations on Health Promotion Interventions for Maternal and Newborn Health. in WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. Accessed: Jan. 26, 2024. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK304983/.

Akasreku BD, Habib H, Ankomah A. Pregnancy in disability: community perceptions and personal experiences in a rural setting in Ghana. J Pregnancy. 2018;2018:1.

Devkota HR, Kett M, Groce N. Societal attitude and behaviours towards women with disabilities in rural Nepal: pregnancy, childbirth and motherhood. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:1–13.

Devkota HR, Murray E, Kett M, Groce N. Are maternal healthcare services accessible to vulnerable group? A study among women with disabilities in rural Nepal. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(7): e0200370.

Ganle J. Addressing socio-cultural barriers to maternal healthcare in Ghana: perspectives of women and healthcare providers. J Womens Health, Issues Care. 2014;6:2.

Ganle JK, Otupiri E, Obeng B, Edusie AK, Ankomah A, Adanu R. Challenges women with disability face in accessing and using maternal healthcare services in Ghana: a qualitative study. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(6): e0158361.

Ganle JK, Parker M, Fitzpatrick R, Otupiri E. A qualitative study of health system barriers to accessibility and utilization of maternal and newborn healthcare services in Ghana after user-fee abolition. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):1–17.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the health professionals at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) for their invaluable guidance and support. We also sincerely appreciate their participation and encouragement in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to various aspects of this manuscript. E.A.A, B.O and E.A were instrumental in conceptualizing the study and defining the research questions that served as the foundation for the entire research process. Additionally, E.A.A, E.A and C.A played a key role by actively participating in data collection and analysis. B.O directions and expertise in analytical methods and techniques was invaluable, greatly enhancing the quality of the analysis. This ensured the accuracy and meaningfulness of the results and findings presented. His contributions were vital across all phases - from initial conceptualization to final data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest regarding the research, authorship and publication of this article. This study was carried out objectively and ethically. The authors have no financial, personal, or professional interests that could influence the findings reported here. All authors contributed equitably based on their academic and professional qualifications, without competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Obeng, B., Asante, E.A., Agyemang, E. et al. Maternal health care for women with disabilities: perspectives of health professionals in Ghana. Discov Health Systems 3, 22 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44250-024-00083-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44250-024-00083-9