Abstract

Over half of the Ugandan population is under 18-years-old. Surgical care is provided by district general hospitals, whose activity is coordinated by fourteen regional referral hospitals. Mulago National Referral Hospital in Kampala is the main tertiary centre for paediatric surgery. The paediatric surgical need is vast and unmet, with around 15% of Ugandan children having an untreated surgical condition. Most paediatric surgical procedures are performed for neonatal emergencies and trauma, with widespread task-sharing of anaesthesia services. Facilities face shortages of staff, drugs, theatre equipment, and basic amenities. Surgical treatment is delayed by the combination of delays in seeking care due to factors such as financial constraints, gender inequality and reliance on community healers, delays in reaching care due to long distances, and delays in receiving care due to overcrowding of wards and the sharing of resources with other specialties. Nonetheless, initiatives by the Ugandan paediatric surgical community over the last decade have led to major improvements. These include an increase in capacity thanks to the opening of dedicated paediatric theatres at Mulago and in regional hospitals, the start of a paediatric surgical fellowship at Mulago by the College of Surgeons of East, Central and Southern Africa (COSECSA) and development of surgical camps and courses on management of paediatric surgical emergencies to improve delivery of paediatric surgical care in rural areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Uganda is a country in Eastern Africa bordered by Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and South Sudan. Uganda has a population of 47.1 million with a high density (229.0 per km2) and a strong growth rate (3.0%). The demographic structure of Uganda is typical for a low-income country, with around half of its inhabitants being under 18 years of age [1]. Healthcare metrics for Uganda are akin to those of other Sub-Saharan nations. Life expectancy stands at 63.4 years with a maternal mortality ratio of 336 deaths per 100,000 live births. As of 2016, 74.2% of Ugandan births were attended by skilled health personnel with under-5 and neonatal mortality rates of 64 and 27 per 1000 live births, respectively. In 2018, 44% of Ugandans were reported to have access to universal health care [2]. Per capita health expenditure in Uganda stands at $36.9 (~ 7% of GDP), far below the minimum of $86 recommended by the World Health Organisation (WHO) [3].

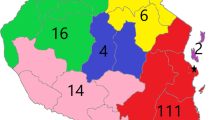

While most first-level surgical care in Uganda is provided by district general hospitals (DGH) in the country’s rural areas, most surgery and anaesthesia providers work in the Kampala-Entebbe metropolis on the shores of Lake Victoria. The activity of DGHs is coordinated by fourteen regional referral hospitals (RRH), which also care for patients from neighbouring countries lacking healthcare infrastructure like South Sudan or the DRC. Mulago National Referral Hospital, teaching hospital for Makerere University in Kampala, is the country’s largest public hospital with 1500 beds (Fig. 1). The paediatric surgery unit (PSU) has a capacity of 64 beds and is the national referral centre for children with surgical disease [4].

2 The paediatric surgical burden in Uganda

The paediatric surgical burden in Uganda is vast and largely unmet. Congenital and acquired paediatric disease is more common in low-resource settings, with 94% of severe birth defects found in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) [5]. Yet, Uganda could until 2015 count on only two fellowship-trained paediatric surgeons and one paediatric anaesthetist. Attempts at quantifying the unmet paediatric surgical need in Uganda have mainly been based on cross-sectional studies relying on household surveys, such as the Surgeons Over-Seas Assessment of Surgical Need (SOSAS) [6]. These studies have consistently identified significant numbers of children with untreated surgical conditions and a high lifetime prevalence of surgical disease, mainly due to congenital anomalies or trauma, which is a cause of disability and preventable mortality (Table 1). Considering the inability of cross-sectional studies to capture emergent surgical disease, these data highlight Uganda’s need for a robust national infrastructure for the delivery of paediatric surgical services.

Facility-based research confirms that Uganda is unable to meet this vast need for paediatric surgical services (Table 2). A cross-sectional study covering Mulago and all 14 RRHs found an average annual volume of 22.0 procedures per 100,000 children. Population-based studies suggest this covers 5–8% of the national paediatric surgical need. Delivery of paediatric surgical care is also characterised by widespread task-sharing of surgical and anaesthesia services [9]. In a system overburdened by high-volume and emergent cases, non-governmental organisations (NGO) and mission hospitals make a critical contribution to elective surgery. For example, a previous study described a clear divide between a public sector covering neonatal disease and emergencies, while mission or NGO hospitals focus on disease-specific elective surgery [10]. Examples in Uganda are cleft lip and palate repair (e.g. SmileTrain, Operation Smile) and paediatric neurosurgery (e.g. CURE International). Public sector facilities in these studies failed to consistently meet WHO standards for level 2 hospitals and faced shortages of personnel, drugs (anaesthetic gas, ketamine, oxygen, blood), equipment (oxygen concentrators, pulse oximeters) and amenities like electricity or running water.

Epidemiological insight on the met paediatric surgical need in Uganda has come from work by John Sekabira’s PSU team at Mulago and from the late Martin Situma’s team at the Mbarara RRH. An analysis of all admissions to the Mulago PSU from the start of a prospective local database in 2012–2016 found that most surgeries were performed in infants under 1 year of age for congenital anomalies. In the context of a 10% post-operative mortality for all children, patients with congenital anomalies were found to have an overall mortality of 27.7% [11]. This is higher than the 17% overall mortality from congenital anomalies shown by pooled data on African countries [12]. While this partly reflects the status of Mulago as a tertiary centre seeing a larger fraction of neonatal emergencies (e.g. intestinal atresia, gastroschisis) studies have investigated the determinants of this high neonatal surgical mortality in Uganda [13,14,15,16]. For example, an analysis of neonatal surgical admissions to Mulago and Mbarara from 2012 to 2017 observed an overall mortality of 36% for admitted neonates who underwent surgery [14]. Overall mortality was highest for gastroschisis at 86%. While this is an improvement from the previous national figure of 98%, it stands in stark contrast to the 4% mortality of HICs [13,14,15,16]. Notably, post-operative mortality from gastroschisis was of only 52%: this does not reflect an advantage of surgical management but rather the selective availability of surgery for neonates with sufficiently good clinical status at presentation. In turn, this is due to the scarcity at Mulago and Mbarara of perioperative support resources including ventilation, total parenteral nutrition, and critical care drugs. While Mulago does have a paediatric and neonatal intensive care unit (ICU) supported by one paediatric anaesthetist, its limited capacity (8 beds) and the lack of specialist trained ICU staff means that most post-operative patients are managed on the ward.

Another critical feature of the paediatric surgical disease burden in Uganda is late presentation. Nearly a third of umbilical and inguinal hernias recorded in the Mulago PSU between 2012 and 2016 were incarcerated or strangulated at diagnosis, suggesting a longer disease course [11]. Similarly, neonates in the Mulago and Mbarara databases presented after travelling a median distance of 40 km, in a country where only 60% of mothers receive antenatal care and 26% do not benefit from skilled birth attendants [14, 17]. Late presentation is a major issue for patients with Hirschsprung’s disease or anorectal malformation (ARM), who require multiple staged procedures. A retrospective review of ARM patients at Mbarara RRH found that most were diagnosed more than 48 h after birth. Definitive treatment by posterior sagittal anorectoplasty (PSARP) was received by only 60% of patients and was delayed relative to HIC standards, albeit with comparable outcomes [18]. In turn, late diagnosis of surgical disease is associated with complications like infection. A retrospective review of the Mulago database found that 20% of the surgical volume of the PSU between 2012 and 2016 was due to infections such as typhoid intestinal perforations or complicated appendicitis. Infections in paediatric surgical patients like abdominal sepsis or necrotising enterocolitis (NEC) were also associated with elevated mortality due to scarcity of critical care resources. [19]. Finally, little is known about patients’ access to follow-up and rehabilitation. Survey- or interview-based studies have estimated that the share of the Ugandan post-surgical paediatric population able to access community services such as assistive devices, rehabilitation programs or school reintegration ranges from 50% in the Kampala-Entebbe area to < 10% in the rural North [20]. These children face obstacles including financial constraints, disability discrimination, and lack of caregiver support [21]. Efforts to scale-up paediatric surgical services in Uganda will thus need to be met with increased accessibility of such community services for children recovering from surgery.

3 Barriers to accessing paediatric surgery and anaesthesia in Uganda

Barriers to accessing surgery for Ugandan children can be analysed under the Three Delays framework theorised for maternal health (Table 3) [22, 23]. Recent studies have applied this framework to understand treatment delays in Mulago and Mbarara. For example, an analysis of visits to the Mulago paediatric surgery outpatient clinic (PSOPC) in 2016 found that patients had first sought care a median of 56 days before reaching the clinic, often presenting multiple times for the same issue. Most patients needing surgery were not admitted to the ward due to capacity constraints and thus experienced delays in care. Compared with clinic outpatients, ward inpatients were also found to have travelled longer distances and faced higher transport costs, often having to sell or borrow assets to cover expenses [24]. A similar study in Mbarara found that delays in seeking care were the most important determinant of delays in treatment, with only 14% of families seeking care immediately. Care-seeking delay was associated with the concern of out-of-pocket costs (e.g. buying surgical supplies), which were incurred by 64% of families [25]. These findings broadly suggest that while all three delays play a significant role in shaping the Ugandan paediatric surgical burden, delays in seeking care predominate and reflect the direct and indirect (e.g. transport) costs of seeking surgery in a low-income country.

Factors influencing delays in seeking paediatric surgical care (first delay) in Uganda can be divided into sociocultural and economic factors. Qualitative studies based on thematic content analysis have described multiple sociocultural determinants of care-seeking delay for families in rural Uganda, including lack of knowledge and stigma about paediatric surgical disease, reliance on traditional remedies, fear of surgery and anaesthesia, and gender inequality [26]. While these are known to act as common barriers to seeking care in LMICs, studies in Uganda have described disease-specific obstacles [27]. For example, a study including both family and local community members for children with congenital anomalies at Mbarara RRH described the belief that surgery would leave to poverty or to the father abandoning the child as major barriers. Several respondents had also previously witnessed a child with congenital anomalies being left to die or had been advised to do so [28]. Such societal pressures increase care-seeking delays for children with congenital anomalies and may contribute to a ‘hidden mortality’. Nonetheless, financial constraints remain the most common barrier to seeking surgery for Ugandan children. Studies among ward inpatients by the Mulago and Mbarara teams reported that several families incurred catastrophic health expenditure, defined as spending over 10% of annual household expenditure, due to the decision to seek surgery. Combining direct and indirect costs, the Mulago study estimated a total out-of-pocket cost of $150.62 per stay [29, 30]. While surgery in Uganda is formally free, financial protection initiatives for families of children seeking care are required if care-seeking delays are to be reduced in coming years.

The delay between the decision to seek care and arrival at a surgical facility (second delay) is influenced by availability of transport infrastructure and shapes the geographic distribution of the Ugandan paediatric surgical burden. As common in LMICs, rurality is associated with long second delays and poor access to surgical care. Household-based epidemiological studies have observed that most children with identified surgical conditions or with an unmet surgical need live in rural areas of Uganda and are prevented from accessing care by the financial impact of travelling to a district general hospital (DGH) or a tertiary centre like Mulago [31]. Studies have applied geospatial analysis to results of surveys to generate a granular description of this rural–urban divide. Children in the rural North, characterised by poor infrastructure, poverty, and conflict, were found to experience longer distances and travel times to reach an appropriate surgical centre and had higher rates of unmet surgical need than the more urbanised Central and Eastern regions [32]. Accessibility and availability of care were also found to be inversely related, with remote facilities in the North having higher ratios of available beds per patient relative to close-by but overcrowded hospitals around Kampala. This demonstrates the interdependence of the three delays: a long second delay due to distance can increase the first delay by disincentivising families from seeking care but may conversely reduce the third delay as surgery is more readily available for children that do to reach a surgical facility.

The delay between arrival at a surgical facility and receipt of appropriate surgery (third delay) in Uganda is determined by the mismatch between a multitude of children seeking care, which include emergencies and elective cases, and the limited workforce and equipment available for paediatric surgery. For example, studies at the Mulago PSOPC found that 37.5% of patients admitted to the ward had their surgery postponed. Reasons included lack of beds, the need to wait for equipment repairs, blood results or imaging, or being told to return for surgical camps. Critically, more than three fourths of postponed patients were told to return after more than a month [24]. The key determinant of the third delay at Ugandan tertiary centres is displacement of elective cases to accommodate children with surgical emergencies or urgent problems. A review of the ward databases at Mulago and Mbarara showed that most admissions were due to emergencies (e.g. incarcerated hernia, intussusception) or urgent problems such as oncology cases (e.g. Wilms’ tumour, sacrococcygeal teratoma). This high burden of emergencies came at the expense of elective cases, with three diverting colostomies for Hirschsprung’s disease or anorectal malformation performed for every definitive repair [33]. This elective backlog is a major problem for patients affected by conditions requiring staged procedures, who often have to live with a stoma for several years, travel long distances and face long hospital stays [34]. One solution that could offload the burden of tertiary centres is investment towards implementing the recommendation, found in the Optimal Resources for Children’s Surgery document by the Global Initiative for Children’s Surgery (GICS), that elective surgery for common conditions in infants should be performed after 1 year of age at DGH level [35].

4 The Ugandan paediatric surgical workforce—training and task-sharing

In the 2015 Hugh Greenwood Lecture given to the British Association of Paediatric Surgeons, the head of the Mulago PSU John Sekabira identified four critical problems challenging the paediatric surgical community in Uganda [4].

-

1)

Late presentation, a universal problem that is especially severe for vulnerable neonates and children with otherwise curable cancers presenting with metastatic disease.

-

2)

Limited facilities and equipment, in particular the lack of a paediatric and/or neonatal ICU at both the Mulago and Mbarara paediatric surgery departments.

-

3)

Workforce shortages, from surgeons to anaesthesia providers and nursing staff. With a paediatric population of 20 million, Uganda would need at least 100 specialist surgeons to meet high-income country standards for service delivery.

-

4)

Lack of awareness about the importance of timely access to paediatric surgery. From first-line doctors to policy makers, people in Uganda assume children’s surgery is a rare need or an exclusive luxury. Awareness-building is further limited by inadequate record-keeping and scarcity of publications as doctors are overburdened by clinical responsibilities.

Concerted efforts by the Ugandan paediatric surgical community in the last decade have led to a major scale-up of its workforce. Curriculum hours for paediatric surgery have increased for medical students and trainees. Under auspices of the College of Surgeons of East, Central and Southern Africa (COSECSA) and in partnership with University of British Columbia (UBC), a paediatric surgery fellowship at Mulago was started in 2015 and is currently graduating 1–2 surgeons per year. There are currently nine fellowship-trained paediatric surgeons in Uganda, including one double-certified paediatric urologist. A COSECSA fellowship in paediatric orthopaedics was also started in 2020 and has currently graduated three specialised surgeons. In 2022, a fellowship in paediatric anaesthesia was started at Mulago by the Association of Anaesthesiologists of Uganda (AAU), in the context of the Paediatric Anaesthesia Training in Africa (PATA) program endorsed by the World Federation of Society of Anaesthesiologists (WFSA) with support from international partners (SmileTrain, Vanderbilt University). The program is currently training five fellows who will join an existing workforce of four paediatric anaesthetists. Finally, there are two paediatric neurosurgeons and one paediatric ENT surgeon who have returned to practice in Uganda following training abroad.

Since eight of Uganda’s nine paediatric surgeons are based in Kampala, several initiatives have focussed on ensuring that this expanded workforce can reduce the caseload of tertiary centres by bringing surgery to rural settings. The first example of this were paediatric surgical camps held in 2008, 2011 and 2013. Organised by the Mulago team, these camps involved both Ugandan and Canadian specialists, trainees, and medical students and treated 677 children for a range of conditions (e.g. hernia, cryptorchidism, hypospadias). Aside from treating children near their home, surgical camps allow local teams to become more comfortable with paediatric procedures and contribute to building North–South partnerships for teaching and research [36].

Another focus for the Ugandan paediatric surgical community has been training and support of adult general surgeons or physicians working in rural settings. This task-sharing solution has been endorsed by global guidelines as a way to reduce the burden of elective procedures on tertiary centres and to improve outcomes from paediatric surgical emergencies [35]. Analysis of a prospective database instituted at Soroti RRH and St Mary’s Hospital Lacor, two key referral centres in Eastern and Northern Uganda, demonstrated that each centre performed more than 700 paediatric procedures between 2016 and 2019. These were mostly standard general surgery cases (e.g. hernia, intussusception) with 30–50% of cases being emergency procedures for infection, trauma, or burns. While surgery was performed by general surgeons as both centres lack specialist paediatric surgeons, mortality was low at 2.4% for Soroti and 1% for Lacor. This high paediatric surgical volume was estimated to have averted 12,400 disability-adjusted life-years (DALY) for an annual benefit of $10.2 million [37]. The need to further train general surgeons and medical officers in managing common paediatric surgical emergencies (e.g. intussusception, hernias) led the Mulago and Mbarara teams to develop a Paediatric Emergency Surgical Care (PESC) course to ensure that children treated by non-specialist providers need not reach a tertiary centre or are appropriately managed before they do. First delivered in 2018, the PESC course is a 2 day course that includes modules on perioperative management, neonatal emergencies (e.g. Hirschsprung’s), intestinal emergencies (e.g. incarcerated hernias) and burns/trauma. While participants observed that scarcity of equipment would act as a barrier to applying teaching from the course in their practice, their knowledge improved significantly from pre (55.4%) to post-course tests (71.9%) [38]. Considering that features of the Ugandan paediatric surgical burden are common to most Sub-Saharan LICs, a standardised expanded version of the course, also including hands-on teaching and simulation, may be exported to other countries in the context of a train-the-trainer program that could form the basis for future South-South global surgical partnerships.

5 Current outlook—strengthening surgical care for Ugandan children

In the long term, improvements in paediatric surgical services in Uganda will require systemic initiatives from the Ministry of Health (MoH), infrastructural investment to reduce the three delays and address existing resource deficits, and autochthonous projects developed by the Ugandan paediatric surgical workforce to gain support among local stakeholders and improve outcomes for children in rural areas. Uganda has a national healthcare plan that includes service delivery standards for scale-up of surgical, anaesthesia and obstetric care [9]. Regrettably, however, a defined package for paediatric surgery was absent in Health Sector Development Plan 2015/16–2019/20 and the MoH Strategic Plan for 2020–25 [39, 40]. In 2023, however, the MoH in collaboration with NGO Kids Operating Room (KidsOR) announced a new 5 year Children’s Surgery National Plan that supports some of the solutions that have contributed to recent improvements in the Ugandan paediatric surgery landscape, including the commitment to establish paediatric theatres and ICUs in all RRHs, support for the COSECSA fellowship, and encouragement for initiatives aiming to equip general surgical teams at the DGH level to manage children with common surgical disease, such as the PESC course [41].

Another key characteristic of the Ugandan paediatric surgical community is its focus on multi-institutional collaborations. In September 2015, a conference was held in Kampala to unify stakeholders across institutions (Ugandan hospitals, academic institutions, NGO faith-based organisations,) and specialties (surgery, anaesthesia, nursing, oncology, neonatology) in the previously fragmented landscape of children’s surgical care in Uganda. Focusing on the themes of infrastructure, service delivery, workforce training and retention, and research and advocacy, the conference unified this informal network into the Paediatric Surgical Foundation, which coordinates the surgical outreach camps, PESC course and other projects [42]. An advance that epitomises the ability of such partnerships to facilitate integration of best practice standards is the Mulago Paediatric Tumour Board (MPTB). Started in 2011 at the Uganda Cancer Institute, MPTB meets weekly to discuss solid tumour patients with involvement of paediatric oncology, surgery, and radiology. Since its creation, treatment abandonment has dropped from ~ 60% to ~ 20% and the 2 year event-free survival for patients finishing treatment has increased to over 70% [4]. A retrospective review of decisions by the board found that 57% of management decisions were implemented, 12% of which resulted in changes in diagnosis and 41% in major changes in management [43]. While the MPTB still needs significant efforts in improving documentation and implementation of its decisions, these findings highlight that optimal multidisciplinary management of paediatric cancer can be achieved in LMIC settings.

An optimistic outlook on paediatric surgery in Uganda is further allowed by the finding that the recent successes of collaborations with NGOs have been driven by local need and focused on strengthening the infrastructure for service delivery. This is exemplified by the work of the Scottish charity The Archie Foundation and KidsOR. In 2015, the Archie Foundation was instrumental in the opening of Uganda’s first dedicated paediatric operating theatre at Naguru hospital in Kampala, which treated patients from the PSU ward at Mulago, in response to local data showing high mortality from neonatal emergencies due to limited access to surgery. A cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) using a decision tree-based model found that the paediatric theatre at Naguru averted a total of 6551 DALYs for an annual cost of $244,001. This equates to an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of $37.25 per averted DALY ($2321 per life saved), which is not only far below WHO cost-effectiveness thresholds but also ten times more effective than a common intervention like HIV antiretroviral therapy [44, 45]. These data have supported further increases in surgical capacity for Ugandan children through the opening of four more theatres by KidsOR (3 in Mulago, 1 in Mbarara). Furthermore, KidsOR has since 2021 been partnering with Smile Train to provide scholarships for Ugandan trainees in the COSECSA paediatric surgery fellowship [46]. Significant advances in service delivery have also been observed for Mbarara RRH. With support from American charity BethanyKids, the paediatric surgery team at Mbarara have started integrating trainees from the COSECSA fellowship and have also developed surgical outreach camps and a wheelchair program to support physical rehabilitation of post-operative patients [47]. In 2021, paediatric surgical beds in Uganda were then tripled with the opening by the NGO EMERGENCY of a Children’s Surgical Hospital (CSH) in Entebbe, which includes three specialist theatres and a neonatal ICU. While initially only dealing with self-referred elective cases, the Entebbe CSH has gradually begun to coordinate its activity with Mulago and the Ugandan paediatric surgical infrastructure. As of 2023, initiatives for training of ICU nurses and integration of the CSH within the COSECSA fellowship are underway (L. Napolitano, personal communication).

6 Conclusion

Uganda is a low-income country with a vast unmet need for paediatric surgery and intersecting sociocultural, financial, and infrastructural barriers that result in long treatment delays and chronic equipment and workforce deficits. However, progress in the last decade is gradually shifting the landscape towards one closer to that of neighbouring middle-income countries (e.g. Kenya). Thanks to a well-coordinated stakeholder group, an effective training pathway has been instituted, several rural outreach programs have been instituted and a florid research environment is producing growing numbers of publications. Furthermore, growth and intensification of international partnerships is leading to consistent increases in facilities for paediatric surgery, which is translating to cost-effective improvements in service delivery and patient outcomes. This progress not only allows for optimism about the future of surgery for Ugandan children but is also a blueprint for other LMICs investigating strategies to scale up their paediatric surgical services in the long term.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

References

World Bank. Uganda – Country overview 2021; https://www.google.com/search?q=uganda+world+bank+overview&oq=uganda+world+bank+&aqs=chrome.1.69i57j0i19i512l2j0i19i22i30l2j0i15i19i22i30l2j69i60.3505j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8.

United Nations. Uganda - SDG Factsheet. 2020 [cited 2022 17th October]; https://uganda.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-10/Uganda%20SDG%20Fact%20Sheet.pdf.

Khisa, I., Uganda’s per capita health expenditure far below WHO’s recommended standard, in The Independent. 2022.

Sekabira J. Paediatric surgery in Uganda. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50(2):236–9.

World Health Organization. Birth Defects – Factsheet. 2012 [cited 2022 24th October]; https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/birth-defects.

Fuller AT, et al. Surgeons OverSeas assessment of surgical need (SOSAS) Uganda: update for household survey. World J Surg. 2015;39(12):2900–7.

Butler EK, et al. Quantifying the pediatric surgical need in Uganda: results of a nationwide cross-sectional, household survey. Pediatr Surg Int. 2016;32(11):1075–85.

Ajiko MM, et al. Prevalence of paediatric surgical conditions in eastern Uganda: a cross-sectional study. World J Surg. 2022;46(3):701–8.

Ajiko MM, et al. Surgical procedures for children in the public healthcare sector: a nationwide, facility-based study in Uganda. BMJ Open. 2021;11(7):e048540.

Walker IA, et al. Paediatric surgery and anaesthesia in south-western Uganda: a cross-sectional survey. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(12):897–906.

Cheung M, et al. Epidemiology and mortality of pediatric surgical conditions: insights from a tertiary center in Uganda. Pediatr Surg Int. 2019;35(11):1279–89.

Livingston MH, et al. Mortality of pediatric surgical conditions in low and middle income countries in Africa. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50(5):760–4.

Badrinath R, et al. Outcomes and unmet need for neonatal surgery in a resource-limited environment: estimates of global health disparities from Kampala, Uganda. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49(12):1825–30.

Ullrich SJ, et al. Burden and outcomes of neonatal surgery in Uganda: results of a five-year prospective study. J Surg Res. 2020;246:93–9.

Wesonga AS, et al. Gastroschisis in Uganda: opportunities for improved survival. J Pediatr Surg. 2016;51(11):1772–7.

Wright NJ, et al. Mortality from gastrointestinal congenital anomalies at 264 hospitals in 74 low-income, middle-income, and high-income countries: a multicentre, international, prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2021;398(10297):325–39.

Kinney MV, et al. Sub-Saharan Africa’s mothers, newborns, and children: where and why do they die? PLoS Med. 2010;7(6):e1000294.

Kayima P, et al. Patterns and treatment outcomes of anorectal malformations in Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital, Uganda. J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54(4):838–44.

Kakembo N, et al. Burden of surgical infections in a tertiary-care pediatric surgery service in Uganda. Surg Infect. 2020;21(2):130–5.

Smith ER, et al. Availability of post-hospital services supporting community reintegration for children with identified surgical need in Uganda. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):727.

Barton SJ, et al. Perceived barriers and supports to accessing community-based services for Uganda’s pediatric post-surgical population. Disabil Rehabil. 2021;43(15):2172–83.

Barnes-Josiah D, Myntti C, Augustin A. The “three delays” as a framework for examining maternal mortality in Haiti. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46(8):981–93.

Meara JG, et al. Global surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet. 2015;386(9993):569–624.

Kakembo N, et al. Barriers to pediatric surgical care in low-income countries: the three delays’ impact in Uganda. J Surg Res. 2019;242:193–9.

Pilkington M, et al. Quantifying delays and self-identified barriers to timely access to pediatric surgery at Mbarara Regional Referral hospital, Uganda. J Pediatr Surg. 2018;53(5):1073–9.

Ajiko MM, Löfgren J, Ekblad S. Barriers and potential solutions for improved surgical care for children with hernia in Eastern Uganda. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):11344.

Grimes CE, et al. Systematic review of barriers to surgical care in low-income and middle-income countries. World J Surg. 2011;35(5):941–50.

Commander SJ, et al. Social and financial barriers may contribute to a “hidden mortality” in Uganda for children with congenital anomalies. Surgery. 2021;169(2):311–7.

Yap A, et al. From procedure to poverty: out-of-pocket and catastrophic expenditure for pediatric surgery in Uganda. J Surg Res. 2018;232:484–91.

MacKinnon N, et al. Out-of-pocket and catastrophic expenses incurred by seeking pediatric and adult surgical care at a public, tertiary care centre in Uganda. World J Surg. 2018;42(11):3520–7.

Bearden A, et al. Rural and urban differences in treatment status among children with surgical conditions in Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(11):e0205132.

Smith ER, et al. Geospatial analysis of unmet pediatric surgical need in Uganda. J Pediatr Surg. 2017;52(10):1691–8.

Grabski DF, et al. Burden of emergency pediatric surgical procedures on surgical capacity in Uganda: a new metric for health system performance. Surgery. 2020;167(3):668–74.

Muzira A, et al. The socioeconomic impact of a pediatric ostomy in Uganda: a pilot study. Pediatr Surg Int. 2018;34(4):457–66.

Global Initiative for Children’s Surgery. Optimal resources for children’s surgical care: executive summary. World J Surg. 2019;43(4):978–80.

Blair GK, et al. Pediatric surgical camps as one model of global surgical partnership: a way forward. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49(5):786–90.

Grabski DF, et al. Access to pediatric surgery delivered by general surgeons and anesthesia providers in Uganda: results from 2 rural regional hospitals. Surgery. 2021;170(5):1397–404.

Ullrich S, et al. Implementation of a contextually appropriate pediatric emergency surgical care course in Uganda. J Pediatr Surg. 2021;56(4):811–5.

Ugandan Ministry of Health. Health Sector Development Plan 2015/16 – 2019/20. 2015; Available from: https://www.health.go.ug/cause/health-sector-development-plan-2015-16-2019-20/.

Ugandan Ministry of Health, Ministry of health strategic plan 2020/21 - 2024/25. 2020.

Ester Nakkazi. Uganda launches $5 million strategic plan to enhance children surgery. Health Journalism Network Uganda 2023; https://hejnu.ug/moh-launches-first-ever-5-million-strategic-plan-to-enhance-children-surgery/#:~:text=The%20Uganda%20Ministry%20of%20Health,well%20as%20training%20of%20paediatric.

Kisa P, et al. Unifying children’s surgery and anesthesia stakeholders across institutions and clinical disciplines: challenges and solutions from Uganda. World J Surg. 2019;43(6):1435–49.

George PE, et al. Analysis of management decisions and outcomes of a weekly multidisciplinary pediatric tumor board meeting in Uganda. Future Sci OA. 2019;5(9):417.

Yap A, et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of a pediatric operating room in Uganda. Surgery. 2018;164(5):953–9.

Yap A, et al. Best buy in public health or luxury expense?: the cost-effectiveness of a pediatric operating room in uganda from the societal perspective. Ann Surg. 2021;273(2):379–86.

KidsOR. 2024 Smile Train and Kids Operating Room Paediatric Surgical Scholarships. 2024; www.kidsor.org/assets/uploads/files/2024%20ST-KidsOR%20Scholarship%20Announcement.pdf.

BethanyKids. Operation: Uganda. 2021; https://bethanykids.org/uganda/.

Funding

There was no external funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.A wrote the main text of the manuscript. P.K. edited the manuscript. Both authors reviewed the final text of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Research involving human participants and/or animals

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals.

Informed consent

No informed consent was necessary for this study.

Competing interests

There are no competing interests to be reported.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alberti, P., Kisa, P. Paediatric surgery in Uganda: current challenges and opportunities. Discov Health Systems 3, 29 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44250-024-00076-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44250-024-00076-8