Abstract

The primary goal of this study was to investigate the severity of being overweight/obese among non-pregnant women and its trend for change over the last 10 years in Bangladesh. This research featured 16,398 female participants and used the chi-Squared test to investigate the association between different socioeconomic variables and dependent variables. We applied the average annual rate of increase (AARI) to determine the trends of selected variables over the last decade. Next, we applied a multilevel logistic regression model to determine specific trigger factors at the individual and community levels; for this, we used the 2017–2018 data from the Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS). Individually, women between the ages of 40 and 44 years (odds ratio [OR] 5.68; 95% confidence interval [95% CI] 4.68–6.89) with better education (OR 1.55; 95% CI 1.34–1.80) and from the wealthiest households (OR 3.65; 95% CI 3.17–4.20) had a higher risk for being overweight or obese. On the other hand, working women (OR 0.80; 95% CI 0.75–0.87) had a lower risk of becoming overweight or obese. Respondents from affluent communities had a higher probability of being overweight or obese (OR 1.93; 95% CI 1.72–2.18) whereas women in rural areas were less likely (OR 0.63; 95% CI 0.57–0.69) to be overweight or obese. The efforts of both individuals and communities are expected to raise awareness among wealthy and educated women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Obesity has continued to increase since becoming a global epidemic, almost tripling worldwide between 1975 and 2020. Overweight subjects accounted for over 1.9 billion individuals aged greater or equal 18 years, including approximately 650 million people affected by obesity. Worldwide, 39% of adults are overweight (39% of males and 40% of females); 13% are obese (11% of males and 15% of females) [1, 2]. In 1997, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially recognized obesity as a global disease and pointed out that obesity is increasing rapidly among nations [3]. Obesity has reached epidemic proportions, prompting increased anxiety over its severe health and economic implications. Obesity contributes significantly to the worldwide prevalence of untreated non-communicable disorders and disabilities (NCDs), in addition to coronary heart disease, some cancers, stroke, hypertension, type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia. The seriousness of being overweight/obese in women has been associated with increased cancers [4, 5].

The latest data shows that the prevalence of obesity in adults is higher in developed countries, such as the United States which has a prevalence of 37% compared to 30% in the United Kingdom, 31% in Canada, 26% in Germany, 30% in Australia and 23% in France [2, 6]. Although obesity and being overweight were once considered a sign of prosperity, they are now widely recognized as severe health problems; men and women are both in danger, particularly those in low- and lower-middle-income nations [6, 7]. In low- and middle-income nations, the rates of overweight and obesity among adult women range from 4.7% in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) to 88.3% in Tonga. More than 50% of the world’s 671 million obese people live in ten different countries; eight of these are low- and middle-income countries: Brazil, China, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Pakistan, and Russia [8].

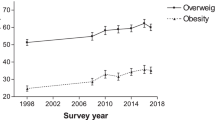

The prevalence of overweight/obesity, particularly among women, is also expanding in Bangladesh, a middle-income country [9,10,11]. According to the Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS), between 2007 and 2017–18, the proportion of overweight or obese subjects increased from 12 to 32% of the population in Bangladesh; this was also associated with an increased risk of chronic illnesses, including hypertension and cardiovascular disease. Furthermore, the rising rate of overweight/obesity in Bangladesh could be influenced by a number of factors, including rapid urbanization, a lack of physical movement, maternal obesity, and a lack of knowledge relating to unhealthy eating habits [12,13,14,15,16].

However, there has been no specific investigation of overweight/obesity in Bangladesh or the factors involved. The primary goals of this research were to (i) determine the sociodemographic factors that influence obesity utilizing BDHS 2017–18 data and (ii) identify the gradual changes in the average annual rate of increase (AARI) of sociodemographic factors for those who were overweight or obese from 2007 to 2017–18 using BDHS data.

2 Methods

2.1 Data Source and Setting

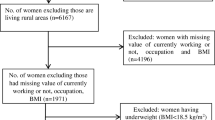

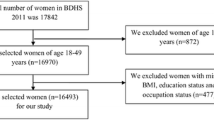

This study drew on four rounds of the Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS): 2007, 2011, 2014, and 2017–18, a cross-sectional national health inspection. The surveys relied on face-to-face interviews. These data incorporate enumeration areas (EAs) that consist of an average of 100–120 households. Large primary sampling units (PSUs) were divided by probability proportional to size. A two-stage stratified sampling of households was performed. In the first stage, 675 EAs were selected using probability proportional to size, consisting of 250 and 425 EAs in urban and rural areas, respectively. In the second stage, an average of 30 households was selected using systematic sampling within each PSU. Data were collected in five phases by highly trained field staff; the overall duration of the survey was 4 months [15,16,17,18]. A total of 20,160 households were selected, and 19,457 households were interviewed. Next, 20,127 eligible women were interviewed (urban 7374 and rural 12,753) [16]. As the overall response rate was 98.8%, a missing value was present (329) and had to be removed from the analysis. After cleansing, the number of respondents was 19,798. Finally, after removing individuals who were pregnant (1116) and those with a body mass index (BMI) < 18.5 kg/m2 (2284), the number of women used in the final analysis was 16,398. Multi-level analysis was performed using data from the BDHS 2017–18 and the AARI using data from the BDHS 2007–2017.

2.2 Dependent Variable

Overweight/obese was considered as the dependent variable. Individuals were classified as being overweight or obese based on their BMI. BMI was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m2).

The BMI of every female was classified according to WHO standards [3]. For multi-level logistic regression, two categories were used: 8.5–24.9 kg/m2 as a normal weight range and 25 kg/m2 and above as overweight/obese.

2.3 Independent Variables

The independent variables were split into two factors based on socioeconomic and demographic data at the individual and community levels.

2.4 Individual Level Variables

Women were classified into the following age groups: 15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, 40–44 and 45–49 years with the degree of education ranging from no education to primary, secondary and higher education. Wealth was categorized as poorest, poorer, medium, richer and richest. The employment status of females was categorized as either “Yes” or “No”. For analytical purposes, religion was recorded as Islam and other religions. Media access was defined as the respondent’s access to a newspaper, radio, or television at least once a week. Media access was created by aggregating the frequency of reading newspapers, the frequency of listening to or watching radio and television and was categorized as “Yes” (has media access) or “No” (no media access).

2.5 Community Level Variables

Household variables were used to create community-level variables. Data relating to a number of household assets were collated from the BDHS 2017–18 dataset initially, including access to electricity, a car/truck/bicycle, refrigerator, toilet facility, floor, roof, and wall materials, and the source of drinking water. Then, we performed factor analysis and principal component analysis; we also created a wealth index for communities that were categorized as poor, medium and rich. Communities were classified as urban or rural based on the location of residences. Finally, households that possessed a TV or radio were identified and aggregated to create a community with a radio or television; these were categorized as “Yes” or “No” [19].

2.6 Statistical Analysis

The chi-squared test was used to identify correlations between variables. AARI was designed by applying the formula, \({Y}_{t+n}={Y}_{t}*{(1+r)}^{n}\), where \({Y}_{t+n}\) indicated the prevalence of overweight/obese in the \({(n+t)\mathrm{th}}\) year, \({Y}_{t}\) was the prevalence of overweight/obese in any given year or the base year, r was the annual rate of change, and n was the number of years between two surveys. To allow flexibility in the investigation, the equation was modified as required and data from the BDHS 2007–17 were used for analysis. We used a two-level multi-level regression model to identify variations at the individual and community levels in the BDHS 2017–18. The model was compared and considered statistically significant by using the probability ratio test for any variances and a P-value of < 0.05. In a multi-level model, intra-cluster correlation (ICC) quantifies the variation caused by individual and community level factors. Further information on ICC and median odds ratio (MOR) can be found elsewhere [19, 20].

2.7 Model Fitness and Specifications

To identify the best model, we performed a null model and detected an ICC of 8.9%. To reduce clustering effects, a two-level multi-level model was introduced. The reduction of Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) indicated significant improvement when compared to the previous model. The model with the least AIC and BIC was determined to be the best.

Microsoft Excel 2016 and IBM SPSS version 26 were used for AARI and bivariate analysis, and STATA version 16 (StataCorp, College Station, United States) was applied for the multi-level regression model.

3 Results

3.1 Bivariate Analysis

Table 1 shows the associations between being overweight/obese and the individual and community characteristics of the females surveyed. Of all age groups, females between 30 and 34 years (7.6%) were the most overweight/obese.

Females with secondary education (14.9%) were more overweight/obese than women with no education (4.6%) or higher education (6.6%). Unemployed females had a higher prevalence of being overweight/obese (20.9%). In addition, in wealthy communities, the severity of being overweight/obese was high (16.4%). Moreover, the chi-squared test indicated a significant (P < 0.001) association between being overweight/obese and the factors age, highest level of education, wealth status, media access, residence, community wealth, community with a radio or television under study. Furthermore, there was no trace of multi-collinearity between individual and community variables as variance inflation factor (VIF) was < 10 and the tolerance < 0.1.

3.1.1 Change in the Rates of Being Overweight/Obese

The AARI for overweight/obese women in Bangladesh is given in Table 2. This rate varied significantly across different periods over the last 10 years. Older females, particularly those aged 45–49 and 40–44 years, exhibited a significant increase in being overweight/obese (8.8% and 7.8%, respectively). A steady rise was seen among younger women of aged 15–19 years (8.2%). A notable increase was also evident among women with primary (9.5%) and secondary education (7.1%). When compared to Muslim women, non-Muslim women had a higher AARI for being overweight/obese (6.6% vs. 8.1%). Women living in the poorest (17.5%) and poorer households (16.5%) showed an increased risk of being overweight/obese relative to those living in the middle (13.6%) and richer (9.9%) households. However, of all households, the wealthiest households (1.1%) showed the lowest increase. In the case of working women, a large rise was seen compared to non-working women (14.7% vs. 3.2%). Furthermore, a sharp rise was seen among women with no media access when compared to women with media access (11.7% vs. 5.6%).

3.2 Multi-level Logistic Regression

3.2.1 Association Measures (Fixed Effects)

Next we took the BDHS 2017–18 data and applied multi-level regression analysis. Table 3 depicts the relationship between individual and community factors and being overweight/obese. A substantial association between these individual factors and being overweight/obese was identified in Model 2. Model 3 also revealed a substantial link between being overweight/obese and communities. Analysis showed that women who were 40–44 years-of-age and 35–39 years-of-age were 5.73-fold (95% CI 4.72–6.96) and 5.50-fold (95% CI 4.57–6.63) more likely to be overweight/obese than women aged 15–19 years after accounting for all categorized individuals and community factors in the final model (Model 4). A respondent with secondary (OR 1.55; 95% CI 1.37–1.74) or higher education (OR 1.53; 95% CI 1.32–1.77) education was more likely to be overweight/obese than women with no education. Non-Muslim women, on the other hand, had a lower chance of being obese (OR 0.88; 95% CI 0.78–0.99) than Muslim women. Women with media access were 1.12-fold (95% CI 1.02–1.24) more likely to be overweight/obese when compared to women with no media access. On the other hand, women in rural areas had a lower risk of being overweight/obese (OR 0.81; 95% CI 0.74–0.88) than women in urban areas. Furthermore, 12% (OR 1.12; 95% CI 1.01–1.25) more communities had access to a television or radio than communities without a television or radio; females living in these communities had a significantly higher risk of being overweight or obese.

3.2.2 Variation Measures (Random Effects)

Model 1 showed that there was a substantial difference in the odds of being overweight/obese throughout communities (P < 0.05), even after accounting for all participant and group-level factors (P < 0.001). In the null model, the ICC revealed that differences between communities were responsible for 8.9% of the variation in being overweight/obese. When both individual and community-level factors were added, the ICC dropped sharply to 1.8%, thus indicating that differences between communities accounted for 1.8% of the total variation. Individual-level factors explained 80% of the variation in those who were overweight/obese in Model 2, but community factors could interpret only 64% of the variation in Model 3. Finally, Model 4 could account for 81% of the total variation in overweight/obese females between communities.

In the null model, the MOR for being overweight/obese was 1.71, thus indicating cluster variation. When all variables were considered, the MOR dropped to 1.26, thus representing a high cluster effect. In other words, when a woman relocated from a lower risk community to a higher risk community, the chances of being overweight or obese increased by 71% and 26%, respectively. Finally, the AIC and BIC for Model 4 were the lowest, thus identifying this Model as the best.

4 Discussion

The study assessed the demographic risk factors for being overweight/obese in non-pregnant females between the ages of 15 and 49 years. We found that 37.1% of women were overweight or obese while 62.9% were healthy. Women of reproductive age, along with those with higher education, a better wealth status, those residing in urban areas, those who worked, and those with access to media were all associated with an increased risk of being overweight/obese. In the case of age, we demonstrated that older women were more overweight/obese; this was consistent with the findings of other studies that showed that obesity was more prevalent in older women [21]. The risk of a female becoming overweight or obese rises with age, possibly due to unhealthy fatty food consumption and a lack of physical activity [22].

Of the 6181 urban women surveyed here, half were overweight or obese (n = 2872). Furthermore, our research indicated that urban women are more at risk of being overweight/obese; this finding also concurs with previous research [4, 11]. Females from urban areas with a high household income may choose to use cars and other fuel-based vehicles, leaving them less opportunity for walking and physical activity and increasing the risk of a higher consumption of fast food. All of these factors may contribute to being overweight/obese, as compared to women from rural regions. Our findings also showed that the prevalence of being overweight/obese in urban respondents was 42%; this was higher than the national average (32%) [10, 16]. This rising trend is supported by the fact that women with a higher socioeconomic status tend to use more improved technologies for a more comfortable lifestyle [23, 24].

According to our findings, 28.3% of women had access to media and were 1.12-fold more likely to be overweight or obese; these findings align with a previous study that found 25.79% and 23.94% of women residing in urban and rural areas had access to media and also concluded that urban and rural women were 1.49- and 1.31-fold more likely to be overweight [9]. A study conducted in Bangladesh in 2017 also suggested that viewing television was linked to obesity because television allows access to worldwide channels instead of allowing subjects to exercise regularly; women enjoy watching television, thus resulting in a sedentary lifestyle. Similarly, our study also revealed that 25.4% of women lived in communities with access to radio or television. Previous research showed that access to TV reduces the consumption of healthy foods and increases the consumption of high-calorie, sugar-added beverages via commercial advertisements [25]. We believe that advertisements for processed foods and prolonged television watching lead to a poor diet and reduced physical activity among Bangladeshi women.

Furthermore, owning a television is associated with a higher socioeconomic background and is also associated with excessive weight and obesity [26]. In the present study, we found that women from wealthy households had higher odds of being overweight/obese than women from lower-income households. Our analysis also identified a significant relationship between community wealth and being overweight/obese; women from affluent communities were more overweight/obese than women from poor and medium communities. Results of a study in India showed that the wealthiest women are more at risk of being overweight than the most impoverished women [27]. This was also consistent with a study reporting a higher interaction between middle- to low-income countries and a link between richness and obesity [28]. This is because an increase in wealth leads to increased energy consumption and processed foods; these are common in middle-income counties [29]. Our study concluded that non-Muslim women had a lower likelihood of being overweight or obese. Studies indicate that staying at home, not maintaining a routine life, skipping meals, and frequently eating are the primary reasons that Muslim women are overweight/obese [30].

Our study also indicated that working women are less likely to be overweight or obese. We believe that this might be because working women are more health-conscious and try to maintain a healthier diet and regular physical exercise so that they can be more focused on their careers [31]. It is possible that women with higher education were engaged in various jobs and had less time to be involved in physical activities [21, 32]. On the other hand, unemployment leads to poor health and well-being and is associated with smoking and drinking. Furthermore, unemployed subjects are known not to generally accept health care services due to the cost involved [33, 34].

This is the first study to investigate the AARI in those that were overweight or obese in Bangladesh between 2007 and 2017. This is critical information for national health policymakers to act on to avoid a future public health crisis.

Over the previous 10 years, there has been a remarkable rise in the numbers of overweight/obese including both younger and older women. This concurs with a study conducted between 2004 and 2014 that showed an expansion in the proportion of younger and older women who were overweight or obese [21]. This previous study also identified a significant increase in overweight and obesity among women with primary, secondary, and higher education, thus concurring with our present findings. Finally, this previous study identified the highest growth among the wealthiest households [21]; in our study, we found that women from each household showed a sharp increase in excessive weight and obesity, except the most affluent families who showed the lowest increase [21].

Our study also has some limitations that need to be considered. A cross-sectional design cannot provide a causal relationship between dependent and independent variables. The presence of a large number of missing values in all four surveys caused difficulty during our analysis. Because our study only included non-pregnant women, the conclusions cannot be applied to all women. Many useful variables were not available in the DHS dataset, including dietary habits, daily hours of physical activity, and the use of the internet or mobile phones. Disease history was not available in the dataset, thus creating a significant limitation. However, apart from these limitations, our analysis used four nationally representative BDHS datasets from 2007 to 2017–18. AARI is a key dimension that represents the rate of increase over the last 10 years. Moreover, a particular strength of our study is that we revealed the relative influences of different community variables on being overweight/obese.

5 Conclusion

The main challenge for policymakers is to address health issues related to excessive weight and obesity in females. These issues can be influenced by a range of significant factors such as wealth status, residence, employment, highest education status and media access. Undoubtedly, the working status of a female is the primary factor that can lead to excessive weight gain or obesity. Furthermore, regular exercise and fitness should be carried out among older women to control excess weight. The affluent community is more affected by this health problem than the poorer community. Appropriate interventions and awareness programs relating to the risks of being overweight/obese should be implemented at the secondary and higher secondary education levels to minimize the growth of excessive weight and obesity. We strongly recommend introducing health education and awareness programs that focus mainly on younger women and the health risks associated with aging. To ensure continuous awareness, the government should introduce mass media campaigns related to dieting and exercising. To raise awareness, government and non-government groups should work together to create a welcoming environment for females who are overweight and obese, especially in cities.

Availability of Data

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in The DHS Program at https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm, reference country Bangladesh.

Abbreviations

- AARI:

-

Average annual rate of increase

- AIC:

-

Akaike information criterion

- BDHS:

-

Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey

- BIC:

-

Bayesian information criterion

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- EA:

-

Enumeration area

- ICC:

-

Intra-cluster correlation

- MOR:

-

Median odds ratio

- NCDs:

-

Non-communicable disorders and disabilities

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PSUs:

-

Primary sampling units

- SE:

-

Standard error

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

- VIF:

-

Variance inflation factor

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Obesity and diabetes in the world: A-Mansia Biotech; 2021. https://www.a-mansia.com/obesity-and-diabetes-in-the-world/.

World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases country profiles 2018. World Health Organization. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274512.

WHO Consultation on Obesity & World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic: report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organization; 2000. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42330.

Mangemba NT, San SM. Societal risk factors for overweight and obesity in women in Zimbabwe: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–8.

Hu FB. Overweight and obesity in women: health risks and consequences. J Womens Health. 2003;12(2):163–72.

Campbell T, Campbell A. Emerging disease burdens and the poor in cities of the developing world. J Urban Health. 2007;84(1):54–64.

Ziraba AK, Fotso JC, Ochako R. Overweight and obesity in urban Africa: a problem of the rich or the poor? BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):1–9.

Ford ND, Patel SA, Narayan KV. Obesity in low-and middle-income countries: burden, drivers, and emerging challenges. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:145–64.

Sarma H, Saquib N, Hasan MM, Saquib J, Rahman AS, Khan JR, et al. Determinants of overweight or obesity among ever-married adult women in Bangladesh. BMC Obesity. 2016;3(1):1–11.

Khan MM, Kraemer A. Factors associated with being underweight, overweight and obese among ever-married non-pregnant urban women in Bangladesh. Singapore Med J. 2009;50(8):804.

Kamal SM, Hassan CH, Alam GM. Dual burden of underweight and overweight among women in Bangladesh: patterns, prevalence, and socio-demographic correlates. J Health Popul Nutr. 2015;33(1):92.

Shafique S, Akhter N, Stallkamp G, de Pee S, Panagides D, Bloem MW. Trends of under-and overweight among rural and urban poor women indicate the double burden of malnutrition in Bangladesh. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(2):449–57.

Banik S, Rahman M. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in Bangladesh: a systematic review of the literature. Curr Obes Rep. 2018;7(4):247–53.

Siddiquee T, Bhowmik B, Moreira NCDV, Mujumder A, Mahtab H, Khan AA, et al. Prevalence of obesity in a rural Asian Indian (Bangladeshi) population and its determinants. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1–9.

National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT) MaA, and Macro International. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2007. Dhaka, Bangladesh and Calverton, Maryland, USA: National Institute of Population Research and Training, Mitra and Associates, and Macro International, 2009.

National Institute of Population Research and Training, ICF. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2017–18: Key Indicators. Dhaka, Bangladesh, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NIPORT, and ICF, 2019.

National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), Mitra and Associates, International aI. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Dhaka, Bangladesh and Calverton, Maryland, USA: NIPORT, Mitra and Associates, and ICF International, 2013.

National Institute of Population Research and Training , Mitra and Associates, and ICF International. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2014: Key Indicators. Dhaka, Bangladesh, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NIPORT, Mitra and Associates, and ICF International, 2015.

Setu SP, Islam M, Halim S, Bin F. Individual and community-level determinants of institutional delivery services among women in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. Int J Clin Pract. 2022;2022:3340578.

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. New York: Wiley; 2000.

Biswas T, Uddin MJ, Mamun AA, Pervin S, Garnett SP. Increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity in Bangladeshi women of reproductive age: findings from 2004 to 2014. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(7): e0181080.

Alemu E, Atnafu A, Yitayal M, Yimam K. Prevalence of overweight and/or obesity and associated factors among high school adolescents in Arada Sub city, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. J Nutr Food Sci. 2014;4(2):1.

Ghose B. Frequency of TV viewing and prevalence of overweight and obesity among adult women in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(1): e014399.

Islam M, Sathi NJ, Abdullah HM, Naime J, Butt ZA. Factors affecting the utilization of antenatal care services during pregnancy in Bangladesh and 28 other low-and middle-income countries: a meta-analysis of demographic and health survey data. Dr Sulaiman Al Habib Med J. 2022;4(1):19–31.

Doak CM, Adair LS, Monteiro C, Popkin BM. Overweight and underweight coexist within households in Brazil, China and Russia. J Nutr. 2000;130(12):2965–71.

Hu FB, Li TY, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Manson JE. Television watching and other sedentary behaviors in relation to risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. JAMA. 2003;289(14):1785–91.

Subramanian SV, Perkins JM, Khan KT. Do burdens of underweight and overweight coexist among lower socioeconomic groups in India? Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(2):369–76.

Reyes Matos U, Mesenburg MA, Victora CG. Socioeconomic inequalities in the prevalence of underweight, overweight, and obesity among women aged 20–49 in low-and middle-income countries. Int J Obes. 2020;44(3):609–16.

Du S, Mroz TA, Zhai F, Popkin BM. Rapid income growth adversely affects diet quality in China—particularly for the poor! Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(7):1505–15.

Rasheed P. Perception of body weight and self-reported eating and exercise behaviour among obese and non-obese women in Saudi Arabia. Public Health. 1998;112(6):409–14.

Puciato D, Rozpara M, Mynarski W, Oleśniewicz P, Markiewicz-Patkowska J, Dębska M. Physical activity of working-age people in view of their income status. BioMed Res Int. 2018;2018:1–7.

Islam M, Sathi NJ, Hossain M, Jabbar A, Renzaho A, Islam SMS. Caesarean delivery and its association with educational attainment, wealth index, and place of residence in Sub-Saharan Africa: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):1–14.

Pharr JR, Moonie S, Bungum TJ. The impact of unemployment on mental and physical health, access to health care and health risk behaviors. Int Scholar Res Notices. 2012;2012:1–7.

Islam MA, Kabir MR, Talukder A. Triggering factors associated with the utilization of antenatal care visits in Bangladesh: an application of negative binomial regression model. Clin Epidemiol Global Health. 2020;8(4):1297–301.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT) Bangladesh and MEASURE DHS for allowing us to use DHS data in our analysis.

Funding

The authors did not receive any funds for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MNAK and HR contributed to the manuscript's conceptualization and writing (review and editing). MAI, HR, and MNAK contributed to data curation and formal analysis. MNAK and HR wrote the original draft. MAI supervised the project. All authors helped in writing (initial draft) of the manuscript, editing, and approval of the final form of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Raihan, H., Khan, M.N.A. & Islam, M.A. Investigating the Factors Affecting Overweight/Obese amidst Non-pregnant Women in Bangladesh: A Multi-level Analysis of Demographic and Health Survey. Dr. Sulaiman Al Habib Med J 4, 159–167 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44229-022-00015-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44229-022-00015-w