Abstract

This study examined the perspectives of Ghanaian higher education students on the use of ChatGPT. The Students’ ChatGPT Experiences Scale (SCES) was developed and validated to evaluate students’ perspectives of ChatGPT as a learning tool. A total of 277 students from universities and colleges participated in the study. Through exploratory factor analysis, a three-factor structure of students' perspectives (ChatGPT academic benefits, ChatGPT academic concerns, and accessibility and attitude towards ChatGPT) was identified. A confirmatory factor analysis was carried out to confirm the identified factors. The majority of students are aware of and recognize the potential of Gen AI tools like ChatGPT in supporting their learning. However, a significant number of students reported using ChatGPT mainly for non-academic purposes, citing concerns such as academic policy violations, excessive reliance on technology, lack of originality in assignments, and potential security risks. Students mainly use ChatGPT for assignments rather than for class or group projects. Students noted that they have not received any training on how to use ChatGPT safely and effectively. The implications for policy and practice are discussed in terms of how well-informed policy guidelines and strategies on the use of Gen AI tools like ChatGPT can support teaching and improve student learning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) has rapidly developed in recent years, leading to various applications in different disciplines, including education [1]. Digital transformation is becoming essential in higher education. These transformations, such as the use of AI technologies, mobile technologies, and online meeting platforms, became inevitable in the post-COVID-19 era [2]. A more recent development is Chat Generative Pre-trained Transformer (ChatGPT), an AI-powered Chabot released by OpenAI equipped with a large language model that enables it to generate original text in response to prompts given by users [3]. The relevant application of ChatGPT in higher education focuses on several areas, including developing assignments [4], supporting essay writing [5], and encouraging critical reflection on AI’s use in society [6]. Despite the advantages, concerns exist about AI-assisted cheating among students [7, 8].

The interest and use of AI technologies continue to surge worldwide [9, 10]; therefore, it is important to consider the societal and policy implications of AI, as well as the potential varying impacts on diverse populations with the deployment of these new technologies. This is particularly crucial for those residing in developing countries, where the debate about the benefits and societal impact of AI needs to be understood in the context of social and economic realities. Synchronizing AI issues and the digital divide debate may be timely for Africa, as both emphasize the use of technologies. The digital divide is a way to understand the existing inequalities not only in African societies but also in communities globally [11]. While recognizing the potential of new AI technologies to transform education, health, and businesses in Africa and potentially impact economic growth, it is vital to highlight the social and economic challenges such as access to technologies, ICT skills, broadband costs, and protecting indigenous data that remain out of reach for most African citizens [12].

Considering that AI relies on extensive data, many have concerns about access, data processing costs, and data management to protect privacy and rights. Although much research has been conducted on AI and ChatGPT in particular, the discussions have not considered the digital divide in the global south. Moreover, empirical discussions have primarily involved academics and professionals [10, 13], with minimal exploration among students. To understand the impact of ChatGPT as a learning tool within the context of the digital divide in the global south, investigating students’ experiences and perspectives is crucial. Students’ perceptions can influence motivation, engagement, and academic achievement, in addition to other factors [14, 15]. When students have positive perceptions of their learning experience, they are more likely to be engaged and motivated, leading to better academic outcomes. Conversely, negative perceptions can result in disengagement, lack of motivation, and lower academic success. This study aims to explore higher education students' perceptions of ChatGPT. The following research questions guided the study:

-

1.

What is the level of awareness of ChatGPT among students?

-

2.

How do students perceive ChatGPT as a learning tool?

-

3.

Are there significant differences in students' perceptions of ChatGPT based on demographics such as gender, age, and level of education?

2 Literature review

This literature review explores the multifaceted dynamics of AI adoption in the global south, with a focus on its implications for higher education, students’ perceptions of ChatGPT as a learning tool, and the influence of demographic variables on AI perceptions. It examines the AI divide in the global south, highlighting disparities in access and adoption, while also delving into the opportunities and challenges of integrating AI in higher education. Additionally, the review investigates students’ awareness, perceptions, and concerns regarding ChatGPT, emphasizing the factors that shape their attitudes towards its utility and ethical implications. Moreover, it analyzes the impact of demographic variables such as gender, age, and educational level on perceptions of AI, underscoring the need for inclusive policies and initiatives to address disparities and promote responsible AI adoption in educational contexts within the global south.

2.1 AI divide in the global south

In 2019, UNESCO identified inequality as one of the world’s most pressing problems, with serious concerns that the spread of digital technology could worsen the issue. The most critical technological challenge is the concept of the digital divide—the extent to which a country, region, group, or individual is either completely or partially excluded from the benefits of digital technology [16, 17]. This has long been the primary perspective through which the relationship between digital technology and inequality is analyzed [18, 19]. There is a growing recognition of the importance of considering the impact of AI on developing countries. The main concern is that most AI systems are Western-oriented, and the potential development of a suitable one in the global south could further exacerbate existing systems of oppression [20].

The global south presents valid concerns for a reason. Despite the promising prospects, several technological interventions in many nations in the global south have failed to deliver the expected results [21,22,23]. Any technological advancement that neglects contextual factors may face failure, regardless of its novelty—a phenomenon evident in many nations in the global south. Langthaler and Bazafkan [24] argued that this region is significantly impacted by the Fourth Industrial Revolution [4IR], characterized by rapid technological advancements like automation, the internet of things, and AI. Körber [25] contended that while the 4IR narrative promises wealth and wellbeing, the global south lacks empirical evidence to substantiate these claims.

It is widely acknowledged that the readiness of the global south to embrace digitalization will greatly influence the impact of digitalization and automation on labor markets [26]. However, hurdles such as inadequate infrastructure, low skill levels, and high capital costs hinder automation in the global south, resulting in a significant digital gap [24, 27]. Without bridging the digital divide, the rapid digitalization of the global economy could lead to profound negative effects on countries within the global south, including substantial job losses. Naudé [28] emphasized that raising educational and skill standards is crucial to ensure that the global south can benefit from the 4IR rather than lagging behind.

To address these challenges, the World Bank [29] proposes an alignment system that focuses on developing robust adaptability, education, and training systems to prioritize lifelong learning policies. Developing nations should prioritize modern intellectual and socio-emotional skills like critical thinking and problem-solving, while developed nations should focus on fundamental academic and socio-emotional skills alongside basic digital literacy [24, 29]. AI holds promise for the global south in various areas such as politics, poverty alleviation, environmental sustainability, transportation, agriculture, healthcare, education, financial transactions, and religious and traditional belief systems. While many of these AI systems are no longer hypothetical but are becoming a reality in Africa, they are primarily driven by companies from the global north [30].

Nevertheless, significant economic and legal challenges hinder the adoption and implementation of AI across the global south. The benefits and risks of AI are substantial, and its development may infringe on fundamental rights and freedoms [30,31,32]. Collaborative efforts are necessary to promote the acceptance and utilization of AI in the global south, including ethical use, regulatory policies, and effective application in education.

2.2 AI in higher education

AI is essential in the academic landscape, enhancing educational efficiency, effectiveness, and productivity. Recent literature [33, 34] has reported that AI could improve education by supplementing the role of human instructors rather than replacing them. New technologies force industries to constantly innovate to keep up with the ever-changing market [35,36,37]. Students and instructors must be the pioneers in facilitating new technologies such as AI to ensure safe and proper use to support teaching and learning.

Several AIs have been rolled out, each with its potentials and drawbacks. However, one AI that has attracted widespread attention is ChatGPT [38,39,40]. Due to its flexibility and content-rich generative ability, ChatGPT has quickly become a ‘student companion’ in developing and developed nations [41, 42]. However, evidence suggests that ChatGPT is not accepted and implemented well especially in higher education. The challenge lies in overcoming the ideological barriers that exist among educators and administrators in order to facilitate successful implementation. Rudolph et al. [43] also highlighted that there is insufficient scholarly research on the implementation of ChatGPT at higher education institutions, partly due to the novelty of the topic. Woithe and Filipec [34] corroborated that even though its features, strengths, limitations, consequences, applications, possibilities, and threats have been examined, current studies cannot be relied upon or replicated.

There are few studies that have investigated the use of ChatGPT in higher education [44,45,46,47]. Higher education students could use ChatGPT as a tool for independent study. In addition to passing higher education courses, Zhai [48] echoed that ChatGPT could assist students to write cohesively and insightfully. Studies in the field of finance have discovered that ChatGPT is useful for brainstorming, literature synthesis, and data identification [49, 50]. Faculty should incorporate AI into teaching and learning activities to challenge students to think critically and creatively as they work to solve authentic challenges.

However, there is also a body of knowledge supporting how ChatGPT can affect effective teaching and learning. For example, Rudolph et al. [43] argued that lower-level cognitive skills are not as well developed. Higher education students have been reported using ChatGPT to commit academic crimes [51, 52]. The inconsistencies in research findings on ChatGPT and effective pedagogy need continuous investigations, especially in academic settings [48, 51, 53, 54]. Nevertheless, for students to successfully appreciate and use ChatGPT in learning situations, they need to be aware of its context of applicability. Their contextual awareness of how they apply ChatGPT could inform their perceptions and any potential concerns about its usage.

2.3 Awareness, perceptions, and concerns of students regarding ChatGPT as a learning tool

Awareness refers to an individual’s capacity to perceive and understand their surroundings [55, 56]. Research conducted in the global north has shed light on students’ awareness and perceptions of ChatGPT. For instance, McGee [57] discovered that university students were aware of ChatGPT and frequently used it for their academic tasks. He found that approximately 89% of students used ChatGPT for homework, while 53% used it for academic assignments. About 48% and 22% of students utilized ChatGPT during tests and for creating paper outlines, respectively.

In addition, Jowarder [58] examined the familiarity, use, perceived utility, and impact of ChatGPT on academic success among undergraduates in the United States. The study revealed that over 90% of participants in semi-structured interviews were familiar with this innovative tool. However, there was a varying level of awareness among students, with some being familiar with and using ChatGPT, while others were not acquainted with it. Cui and Wu [59] also found that respondents in China perceived AI as more beneficial than risky.

Contrastingly, Demaidi [60] found a significant lack of awareness of AI in developing countries, particularly in the global south. This may be attributed to the limited utilization of AI in various industries and the legal framework struggling to keep pace with technological advancements. Makeleni et al. [61] conducted a systematic review on the challenges faced by academics in the global south regarding AI in language teaching. Their findings highlighted four key challenges: limited language options, cases of academic dishonesty, bias and lack of accountability, and a general lack of interest among both students and teachers. Perceptions can vary between positive and negative dimensions. A handful of studies have explored students’ perceptions of ChatGPT as a learning aid. For example, Fiialka et al. [62] noted that educators in higher education who interact with students tend to have a favorable attitude towards AI and its potential. Woithe and Filipec [34] investigated students’ adoption, perceptions, and learning impact of ChatGPT in higher education and found that students had a positive view of its utility, user-friendly interface, and practical benefits.

Research by Popenici and Kerr [63] examined the impact of AI systems on education and highlighted negative perceptions among students and teachers due to concerns about privacy, power dynamics, and control. However, Perin and Lauterbach [64] found that students appreciated the quick feedback provided by an AI grading system. Positive perceptions towards AI systems could facilitate instructors in offering continuous feedback to enhance student learning. Seo et al. [65] reported mixed findings on the impact of AI in teaching and learning, emphasizing concerns about responsibility, agency, and surveillance issues. While AI systems are praised for improving communication quality and providing personalized support, worries about misunderstandings and privacy are also prevalent. These mixed beliefs about AI have been discussed in other studies as well.

Despite the existing literature on AI in education, there is a lack of comprehensive research on students’ awareness, perceptions, and concerns regarding ChatGPT, particularly in the global south. This study aimed to address this gap by investigating the state of awareness, perceptions, and concerns about ChatGPT among higher education students in the global south, recognizing their importance as major stakeholders in the education system.

2.4 The influence of demographic variables on perceptions of AI

There is limited literature on the influence of demographics and other socioeconomic variables on AI perception [66,67,68]. For instance, Brauner et al. [66] conducted a study on the public’s perception of AI and found that individuals with lower levels of trust still perceived AI more positively. These individuals believed that the outcomes of AI were more favorable, although the magnitude of this impact may be small. The authors concluded that AI is still considered a ‘black box,’ making it challenging to accurately evaluate its risks and opportunities. This lack of understanding may result in biased and irrational beliefs regarding the public’s perceptions of AI.

A large-scale study conducted by Gerlich [69], involving 1389 scholars from the US, UK, Germany, and Switzerland, revealed varied public views on AI. The author concluded that factors such as perceived risks, trust, and the scope of applications influenced public awareness and perceptions of AI. In another study focusing on the influence of demographic variables on AI perceptions, Yeh et al. [70] examined public attitudes towards AI and its connection to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The results showed that the public generally held a positive view of AI, despite perceiving it as risky. Additionally, males exhibited greater confidence in AI knowledge compared to females, while more females believed that AI should have a greater impact. Respondents aged 50 to 59 years and college students, as opposed to master’s graduates, held stronger opinions on how AI would impact human lives and alter decision-making processes.

Furthermore, research by Yigitcanlar et al. [71] investigated the factors influencing public perceptions of AI, highlighting that gender, age, AI knowledge, and AI experience play crucial roles. Similar findings were reported by Miro Catalina et al. [72], indicating that females, individuals over 65 years old, and those with university education harbored greater distrust towards AI usage. These results suggest that individuals with diverse demographic backgrounds exhibit varying perceptions of AI, with limited focus on discussions in the global south. Therefore, the current study, which also explores the impact of gender, age, and educational level, holds significant importance.

3 Methods

3.1 Data collection procedures and sampling methods

The research focused on exploring higher education students’ perspectives on ChatGPT. Data was gathered using a quantitative approach through an electronic survey conducted on Qualtrics. The choice of Qualtrics was based on its familiarity to most higher education students [73] and its ability to facilitate remote data collection, which was particularly suitable for higher education students in Ghana. Participant recruitment utilized a combination of snowball and convenience sampling methods. To reach a wider audience, the survey link was shared through various online platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp groups.

Identified respondents were encouraged to further distribute the survey link among their peers. All participants received consent forms and detailed information about the study prior to their participation. They were given the opportunity to review and understand the information before providing their consent. Participants were also assured that they could withdraw from the study at any point without facing any consequences. Throughout the study, confidentiality and anonymity of the participants were prioritized. Their identities were kept undisclosed, and their responses were treated with the utmost privacy and confidentiality.

3.2 Survey instrument

A developed questionnaire, known as the Students’ ChatGPT Experiences Scale (SCES), was utilized for this study. The questionnaire consisted of three parts: demographic information, students’ awareness and usage of ChatGPT, and students’ perspectives on ChatGPT. The section on students’ awareness and usage of ChatGPT included four items that were measured dichotomously, with responses being ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. The students’ perspectives on ChatGPT were assessed using the SCES comprising 33 items. The survey utilized a 4-point Likert-type scale, with responses ranging from ‘Strongly Agree’ (SA) and ‘Agree’ (A) to ‘Disagree’ (D) and ‘Strongly Disagree’ (SD).

The validity and reliability of the scale were considered. Initially, three researchers developed the questionnaires based on existing literature. Subsequently, an expert panel review, consisting of two experts, qualitatively examined the wording of the items. A reliability analysis using Cronbach’s alpha indicated a high level of internal consistency (0.906) for all 33 items. Furthermore, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) were conducted to assess the psychometric properties of the 33 items. The outcomes of the validity and reliability analysis are detailed in the results section.

3.3 Participants

Although 441 students from Ghanaian higher education institutions (i.e., universities and colleges of education) started providing responses to the survey, 277 students completed all sections of the survey. As shown in Table 1, out of the sample of 277 students, there were more males (55.6%) than females (43%). The majority (41.9%) of the students were in their second year. Most (49.1%) of them were within the age range of 20–25 years.

3.4 Data analysis

Prior to conducting the main analysis, EFA and CFA were carried out to evaluate the psychometric properties of the measurement instrument. EFA was conducted using SPSS, with the extraction method of Principal Component Analysis (PCA) being utilized, while considering the sample sizes [74]. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (KMO) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were employed to assess sampling adequacy [75], with a cut-off point of 0.40 set to filter the factor loadings [76]. Eigenvalues greater than 1 and screen plots were used to determine factor solutions, and Monte Carlo’s PCA for Parallel Analysis was conducted to confirm the identified factor solutions based on eigenvalues and screen plots [77]. Items that did not meet the cut-off or did not load significantly onto a factor were eliminated. Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities (α) were used to evaluate item consistencies, with alpha values of 0.70 and above indicating acceptable internal consistency [78], serving as the criteria for evaluating the emerging factors.

The CFA was conducted in AMOS to further validate the factors identified in the EFA. Evaluation criteria such as Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardised Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) were utilized. RMSEA and SRMR were used to assess the absolute fit of the model, while CFI and TLI indicated incremental fit [79]. Lower values of Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) indicated a parsimonious model fit [80]. To determine model fit, it is recommended that CFI should be above 0.95 or 0.90, or possibly satisfactory if above 0.80. SRMR should be below 0.09, and RMSEA should be less than 0.05 for good fit, or between 0.05 and 0.10 for moderate fit [81]. Composite reliability (CR), discriminant, and convergent validity were also utilized to assess the internal consistency and validity of the confirmed items. According to Hair et al. [82], a CR value greater than 0.70, AVE greater than 0.50, and MSV less than AVE indicate acceptable psychometric properties of the developed scales.

Regarding the first research question addressing students’ awareness of ChatGPT, data analysis was conducted using frequencies and percentages in SPSS. For the second research question on students’ perceptions of ChatGPT as a learning tool, factor structures identified from EFA and CFA in AMOS, along with means and standard deviations, were utilized to describe their perceptions. These statistical tools were chosen to summarize and organize data focusing on student awareness and perceptions of ChatGPT [83]. Since the survey utilized a 4-point Likert-type scale, with responses ranging from ‘Strongly Agree’ (SA) and ‘Agree’ (A) to ‘Disagree’ (D) and ‘Strongly Disagree’ (SD), the highest possible score on any item was 4.0, representing unanimous strong agreement among all respondents. Conversely, the lowest possible score on any item was 1.0, indicating unanimous strong disagreement. The cut-off point for determining overall agreement or disagreement was set at 2.50, calculated as either 4.0–1.50 or 1.0 + 1.50. A mean score of 2.50 or higher indicated agreement with the survey statements, while a mean score below 2.50 indicated disagreement.

Both EFA and CFA were employed to explore and confirm the underlying factor structures and relationships that influence students’ perceptions of ChatGPT as a learning tool [84]. Addressing the final research question examining differences in students' perceptions of ChatGPT based on demographics, a Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) was used to assess significant mean differences in perceptions with respect to gender, age, and education level [85]. Checks for normality (using Shapiro–Wilk, skewness and kurtosis), linearity, and homogeneity of variance were performed before analysis. Results indicated that the data approximated a normal distribution and assumptions of equal variances were met, allowing for valid interpretation and appropriate use of inferential statistics. Statistical significance was determined at a 5% alpha level.

4 Results

4.1 EFA and CFA

Based on the EFA, the 33 items that measured students’ perceptions of ChatGPT as a learning tool loaded onto six factors. The scree plot (see Fig. 1) and Monte Carlo PCA for parallel analysis were used to determine the number of factors or components to retain. These parameters supported a three-factor structure. The KMO value was 0.899, and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was also significant (p < 0.001), indicating the appropriateness of interpreting factor analysis results (see Table 2).

Furthermore, Table 3 provides the factor structure, loadings, reliability coefficients (i.e., Cronbach’s alpha), and variance explained of the identified three-factor structure that explains students' perceptions of ChatGPT as a learning tool. Factor 1 was identified as Perceived Academic Benefits of ChatGPT, consisting of 17 items focused on the positive impacts of using ChatGPT for academic purposes. Students highlighted various benefits, such as saving time, convenient access to information, accuracy, better understanding of difficult topics, meeting deadlines, recommending it to others, finding it more useful than alternatives, and improving academic performance. These responses emphasize ChatGPT’s valuable role in supporting student learning.

Factor 2, referred to as Perceived Accessibility and Attitude towards ChatGPT, includes seven items that demonstrate students’ positive attitudes and enthusiasm for using ChatGPT in academic settings. Students appreciate the attractiveness and enjoyment of using ChatGPT, indicating a willingness to embrace AI tools in their educational journey. Factor 3, labeled as Perceived Academic Concerns with ChatGPT, comprises 9 items reflecting students’ fears and reservations about using ChatGPT for academic purposes. Common concerns include plagiarism, hindering critical thinking development, security vulnerabilities, over-reliance on technology, lack of originality, academic policy violations, and privacy risks associated with ChatGPT use.

The reliability estimates for the three factors ranged from 0.812 to 0.917: (a) Perceived Academic Benefits: α = 0.917, (b) Perceived Academic Concerns: α = 0.833, (c) Perceived Accessibility and Attitude: α = 0.812. Collectively, these factors explain 46.5% of the variance in students' perceptions of ChatGPT as a learning tool.

The CFA confirmed the explored factors resulting from the EFA. Significant standardized estimates ranged from 0.323 to 0.769, with p < 0.001. The three-factor model showed a satisfactory fit, with TLI = 0.813, CFI = 0.825, SRMR = 0.0695, RMSEA = 0.071, and low AIC = 1378.054. Additionally, the model demonstrated excellent composite reliability, convergent validity, and divergent validity. For example, composite reliability ranged from 0.836 to 0.919, AVE values ranged from 0.501 to 0.519, and MSV ranged from 0.006 to 0.406, confirming excellent composite reliability, convergent, and divergent validity [81, 82]. Significant correlations were found between the three identified factors. The first and second factors were significantly positively correlated (r = 0.784, p < 0.001). The third and first factors were significantly negatively correlated (r = − 0.012, p < 0.001), while the third and the second factors were significantly positively correlated (r = 0.079, p < 0.001). Figure 2 illustrates the confirmed factor structure from the CFA.

4.2 Research question 1: what is the state of awareness of ChatGPT among students?

The results indicate that students are aware of ChatGPT. As shown in Table 4, approximately 77% indicated that they have heard about ChatGPT. Additionally, more than 60% indicated that they have used ChatGPT. However, the majority of students (89%) indicated that they have not received any training or guidelines on using ChatGPT.

Students were asked to indicate how they have utilized ChatGPT, taking into consideration their awareness of the tool. As shown in Table 5, the majority of students (around 37%) used ChatGPT for personal learning, 22% for assignments, 5% for group work, and 3% class work. Additionally, 34% of students mentioned using ChatGPT for other non-academic reasons.

4.3 Research question 2: what are students’ perceptions of ChatGPT as a learning tool?

Overall, students indicated positive perceptions of using ChatGPT as a learning tool, especially regarding its perceived academic benefits (overall mean = 3.01). As shown in Table 6, they indicated that they are more likely to recommend ChatGPT as it facilitated their academic duties (Item 6, mean = 3.17, SD = 0.65). According to them, ChatGPT helps understand difficult concepts better (Item 4, mean = 3.15, SD = 0.65), saves time and effort in doing assignments (Item 15, mean = 3.14, SD = 0.72), is convenient (Item 2, mean = 3.13, SD = 0.75), and saves time when searching for information (Item 1, mean = 3.12, SD = 0.85).

Despite the generally positive perceptions about ChatGPT, Table 6 shows that students had concerns regarding the use of ChatGPT (overall mean = 2.89). For example, they fear relying too much on ChatGPT and not developing their critical thinking skills (Item 23, mean = 3.01, SD = 0.81). They also shared concerns about security (Item 24, mean = 2.95, SD = 0.78), privacy risks (Item 28, mean = 2.88, SD = 0.76), as well as a lack of originality in their assignments (Item 22, mean = 2.86, SD = 0.85).

Regarding students' perceptions of accessibility, they found ChatGPT accessible (overall mean = 3.09). As shown in Table 6, students indicated it does not take a long time to learn how to use ChatGPT (Item 17, mean = 3.14, SD = 0.70) and does not require extensive technical knowledge (Item 19, mean = 3.01, SD = 0.75). Students also indicated that they find GenAI like ChatGPT fun to use (Item 31, mean = 3.13, SD = 0.71).

4.4 Research question 3: are there any significant differences in students’ perceptions of ChatGPT based on their demographics, such as gender, age, and level of education?

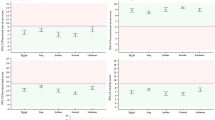

The multivariate results presented in Tables 7, 8, and 9 indicate that there are no significant differences in students’ perceptions of ChatGPT based on gender (F(6, 544) = 1.437, p = 0.198 > 0.05; Wilk’s Λ = 0.969), age (F(12, 175) = 0.455, p = 0.940, Wilk’s Λ = 0.980), and level of education (F(9, 660) = 1.551, p = 0.127, Wilk’s Λ = 0.950). These findings suggest that regardless of students' demographics, their perceptions of ChatGPT may be similar.

5 Discussion

The present study investigated the perspectives of Ghanaian higher education students on ChatGPT as a learning tool. It explored the students’ levels of awareness, perceptions, and variations in perceptions of ChatGPT based on gender, age, and educational level. The findings revealed that the students were indeed familiar with ChatGPT as a learning tool.

The study also found that most students use ChatGPT for their assignments; however, the majority of the students are reluctant to use it for classwork and group work. For example, the question “I often use ChatGPT as a source of information in my assignments and duties” had the highest coefficient (0.768). One possible explanation is that most higher education institutions in Ghana do not have clear guidelines on the use of technologies like smart phones (which is the common devise use among students) in the classrooms [86, 87]. Consequently, many students hesitate to use these devices during instructional sessions, as there may be faculty members who do not endorse their use within the classroom environment. Students therefore may feel comfortable using ChatGPT for their assignment, which is mostly done outside of the classroom. Another potential factor to consider is that the majority of higher education students in Ghana may not possess personal computers. Consequently, they face challenges accessing devices like laptops, which could be utilized to access ChatGPT and enhance their classwork. This finding further highlights the digital divide that continues to be one of the challenges of most developing countries in the global south [18, 19, 21, 24, 27, 30, 32, 38]. The finding also confirms previous studies regarding students’ awareness of ChatGPT, as well as how it has been used in teaching and learning [57, 58, 59]. For example, McGee [57] reported that university students demonstrated awareness of ChatGPT and used it for homework and academic assignments.

Other interesting results that emerged from this study are the perceived academic benefits, positive attitudes, and accessibility of ChatGPT that most of the participants reported. This indicates students’ general positive attitudes toward the use of ChatGPT as a learning tool. For example, students in this study indicated that using ChatGPT has helped them to improve their overall academic performance. Primarily because ChatGPT helps them in better understanding difficult topics and concepts. Also, ChatGPT saves them a lot of time when searching for information. Students also highlighted that they do not face many difficulties when using ChatGPT and find it fun to use. Additionally, ChatGPT does not require extensive technical knowledge. Students feel enthusiastic about using ChatGPT for learning and research. These results align with extant literature that supports higher education students' and instructors' positive perceptions of AI models such as ChatGPT [34, 62, 64].

ChatGPT offers personalized assistance, especially in challenging subjects, and assists students in their assignments, while suggesting areas for improvement [34, 38, 41,42,43]. For example, Baidoo-Anu and Owusu Ansah [38] stated that ChatGPT promotes personalized and interactive learning, generates prompts for formative assessment activities that provide ongoing feedback to inform teaching and learning. It helps create adaptive learning systems based on a student's progress and performance. An adaptive learning system based on a generative model (e.g., ChatGPT) could provide more effective support for students learning programming, resulting in improved performance on programming assessments. This finding is further corroborated by studies examining teachers' dispositions towards the integration of Gen AI in education. For example, the research led by Fiialka et al. [62] found that higher education instructors had a favorable disposition towards AI models and their potential to improve interactions with students. In this study, participants reported that using ChatGPT is convenient for their information search. They found ChatGPT to be accurate and improve their understanding of learning concepts, especially in difficult topics. ChatGPT is a useful alternative learning tool that supports their learning. The participants found ChatGPT to be attractive as it provided an environment of teaching and learning that makes students receptive to the use of AI models to improve their learning. It has long been established that AI models such as ChatGPT are convenient, accessible, user-friendly, fast, and responsive [43, 64, 88]. According to Perin and Lauterbach [64], AI models were perceived positively because they assisted instructors in providing continuous feedback on student learning. Equally important studies that highlighted positive AI model perceptions are those of Ross et al. [88]. They argued that with AI models such as ChatGPT, students could adapt learning contents based on their needs, which increased their motivation and engagement. When students find ChatGPT to be convenient, user-friendly, accessible, and useful in their learning, they are more likely to perceive it as an effective tool that can support their learning.

The study also found that a significant portion of students reported using ChatGPT primarily for non-academic reasons. This finding could be explained by students’ concerns regarding the use of ChatGPT as revealed in the factor analysis. Students in this study indicated that they have concerns regarding the use of ChatGPT such as risk of hindering critical thinking skill development, potential security vulnerabilities, over-dependence on technology, lack of originality in assignments, violations of academic policies, and privacy-related risks associated with using ChatGPT. Extant literature on the use of Gen AI among higher education students has shown similar findings [10, 38, 89, 90]. For example, Hu [10] found that higher education students were concerned about accuracy, privacy, ethical issues, and the impact on personal development. A significant factor contributing to students’ reluctance to leverage Gen AI tools like ChatGPT is the absence of clear policy guidelines from many higher education institutions [10, 38, 39]. Students may therefore hesitate to use Gen AI for academic purposes or may choose not to disclose their use of such tools in academic settings due to concerns about academic integrity.

Also, ChatGPT may fail to provide accurate information to improve student learning. The responses in ChatGPT are based on what is available in its training data and may lack a true understanding of the real academic world. There is a greater likelihood that ChatGPT may result in the propagation of misleading and inaccurate information without tangible academic sources and rigor, which can be detrimental to student learning. Bai et al. [91] study that investigated the cognitive effect of ChatGPT on learning and memory revealed that AI models, including ChatGPT, are promising in supporting personalized student learning and access to academic information. However, users of ChatGPT may be exposed to several risks such as reduced critical thinking capabilities and decline of memory retention as the results of this study have shown. It is important to acknowledge that ChatGPT can be a powerful teaching and learning tool for students in the global south; it simultaneously raises serious concerns such as overreliance on ChatGPT, academic integrity, accuracy of information, etc., especially because students in this study have not received any training or institutional guidelines on how to use ChatGPT safely and constructively.

In analyzing students’ demographics and their views on ChatGPT, there were no significant variations in how students perceive ChatGPT among different demographic groups. This suggests that regardless of factors like gender, age, or education level, students have consistent views on ChatGPT. Essentially, students from diverse backgrounds share similar opinions on the advantages, concerns, and accessibility of ChatGPT as a learning tool. This consistency in viewpoints highlights the strength and universality of students’ perspectives on ChatGPT, indicating that its benefits and challenges go beyond demographic differences. These findings emphasize the potential for ChatGPT to be widely accepted among various student populations, demonstrating its versatility and inclusivity in educational settings. Furthermore, the absence of demographic distinctions implies that efforts to incorporate ChatGPT into educational practices do not need to be customized for specific demographic groups, making implementation strategies simpler and promoting equal access to AI-supported learning opportunities for all students. Based on the findings presented, we challenge previous studies that suggest variations in the perceptions of AI models, such as ChatGPT, based on demographic factors like gender and age [70,71,72].

6 Conclusion and implications for policy and practice

The study highlights the need for education stakeholders, particularly in the global south, to embrace innovative pedagogies leveraging AI tools like ChatGPT to enhance learning outcomes and bridge the digital divide. This study provides valuable insights into the awareness and potential role of AI, specifically ChatGPT, in the global south, particularly among tertiary education students. Educational policy makers can leverage students’ awareness of ChatGPT to promote individualized learning and growth. Students could be prepared to align themselves with innovative pedagogies aimed at developing 21st-century skills and core competencies.

Evidence from this study also shows that the majority of students are using ChatGPT for their academic work. However, they are yet to receive any training or institutional guidelines on how to use it safely and constructively to support their learning. Scholars have argued that students will not benefit from the advancement of AI, especially ChatGPT, if they are not trained on appropriate use within the academic space. Atlas [9] maintained that educating students on the appropriate utilization of ChatGPT is helpful in ensuring students use it safely to support their learning. This can be accomplished through workshops, training sessions, or integrating content related to academic integrity and plagiarism into the curriculum. DeLuca et al. [91] argued that encouraging students to collectively define learning objectives and establish criteria for the task, considering the role of AI software, would empower them to assess and discern suitable contexts in which AI such as ChatGPT can serve as a valuable learning tool.

Moreover, as highlighted in this study, students' concerns (especially around academic integrity) about the use of Gen AI tools like ChatGPT can limit their potential use of these tools for academic purposes. To support students in leveraging Gen AI in higher education settings, policymakers can develop well-informed policy guidelines and strategies for the responsible and effective implementation of Gen AI tools. For example, it is important to teach students to use AI-generated content for brainstorming and understanding concepts, rather than relying on it for original research or writing. Clear direction and creating a supportive environment are essential when incorporating Gen AI tools into education. While establishing a policy framework is crucial, providing specific guidance and support within those policies is equally important to ensure their successful implementation and impact. Educators can effectively enhance student learning experiences by using Gen AI models like ChatGPT in a thoughtful and strategic manner.

Additionally, establishing a secure and efficient environment for integrating ChatGPT into educational settings requires the implementation of a comprehensive strategy that focuses on privacy, security, and academic integrity. This strategy includes providing training on ethical use, incorporating privacy measures such as encryption and consent mechanisms, and implementing content moderation to maintain accuracy and appropriateness. Integration with existing platforms allows educators to oversee usage, while feedback mechanisms enable users to promptly report any issues. Continuous monitoring and collaboration with stakeholders ensure adherence to best practices, promoting responsible usage and maximizing ChatGPT’s potential for learning and knowledge acquisition while minimizing risks. By doing so, higher education institutions can enhance teaching and learning experiences.

Other scholars have also emphasized that capacity building or institutional guidelines on the use of Gen AI tools like ChatGPT are not only beneficial to students but teachers as well. For example, according to Baidoo-Anu and Owusu Ansah [38], by enhancing their professional capabilities, teachers can acquire the necessary skills to effectively leverage ChatGPT and other Gen AI technologies for facilitating advanced pedagogical methods that enhance student learning. Moreover, as the prevalence of AI continues to grow in various professional domains, incorporating Gen AI tools into the educational setting and guiding students on their constructive and safe utilization can also equip them for success not only in educational settings but also in future workforce dominated by AI [38]. Consequently, educators could utilize Gen AI models such as ChatGPT to bolster and enhance the learning experiences of their students.

The study further highlights a paradigm shift in the educational landscape, signaling the need for education stakeholders, especially instructors and administrators in the global south, to embrace learner-centered technology-based pedagogies. Education administrators are encouraged to not only create technologically rich learning environments but also to implement student engagement programs that orient students on the productive use of ChatGPT. This approach promotes the appropriate use of ChatGPT, addressing individual learning needs, offering immediate feedback, and facilitating better understanding of concept.

Finally, the satisfactory psychometric properties and model fit demonstrated during the validation of the SCES highlight its credibility and effectiveness as a comprehensive tool for evaluating students’ perceptions of ChatGPT as an educational resource. These results not only advance research in AI-enhanced education but also provide useful insights for educators and policymakers looking to use Gen AI tools like ChatGPT efficiently in order to improve student learning experiences. With these findings, researchers can use the SCES as a reliable tool to study different aspects of students’ experiences with ChatGPT and analyze how perceptions evolve over time and factors influencing them. Educators and policymakers can use the validated SCES to assess the impact of ChatGPT implementation on student learning experiences and outcomes, identify areas for improvement, and tailor instructional strategies accordingly. These findings add to the limited research available on the development of a reliable scale to assess students’ interactions with ChatGPT in the context of AI-driven education [92, 93].

7 Limitations and future research

While this study’s cross-sectional design offers valuable insights, it is limited in its ability to establish causal relationships. The variables under examination were assessed solely through self-reported instruments distributed via an online survey, potentially introducing social desirability biases in student responses. Although the SCES has been validated among university students, it is important to recognize the potential for errors due to confounders, endogeneity biases, over reporting, underreporting biases, and other factors inherent in cross-sectional designs. Additionally, the study is constrained by its reliance on self-reporting, which may not always accurately reflect participants’ behaviors and experiences. Furthermore, the sample was drawn exclusively from Ghanaian higher education students, limiting the generalizability of the findings to other regions or demographic groups within the global south. A follow-up interview to clarify quantitative results and a consideration of faculty perspectives on ChatGPT could enhance the richness of this investigation.

Despite these limitations, this study significantly enhances our knowledge of university students’ awareness and utilization of ChatGPT in the global south. Subsequent research could explore potential technological interventions to address the educational risks associated with ChatGPT use in Africa. Longitudinal mixed-method studies involving input from higher education students and faculty could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamics and long-term impacts of ChatGPT adoption among different interest groups.

Data availability

The quantitative data used in our analysis is available based on a reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Zawacki-Richter O, Marín VI, Bond M, Gouverneur F. Systematic review of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education—where are the educators? Int J Educ Technol High Educ. 2019;16:39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-019-0171-0.

Agbaglo E, Bonsu EM. The role of digital technologies in higher education during the coronavirus pandemic: insights from a Ghanaian university. Soc Educ Res. 2022;2(2):45–57. https://doi.org/10.37256/ser.3320221402.

OpenAI. ChatGPT: Optimizing language models for dialogue. 2023. from https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt/. Accessed 10 Mar 2023

Sullivan M, Kelly A, McLaughlan P. ChatGPT in higher education: considerations for academic integrity and student learning. J Appl Learn Teach. 2023;6(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.37074/jalt.2023.6.1.17.

Crawford J, Cowling M, Allen KA. Leadership is needed for ethical ChatGPT: Character, assessment, and learning using artificial intelligence (AI). J Univ Teach Learn Pract. 2023;20(3):113–45. https://doi.org/10.53761/1.20.3.02.

van Dis EAM, Bollen J, Zuidema W, van Rooij R, Bockting CL. ChatGPT: five priorities for research. Nature. 2023;614(7947):224–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-00288-7.

Mhlanga D. Open AI in education, the responsible and ethical use of ChatGPT towards lifelong learning. SSRN, 4354422. 2023. from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm. Accessed 15 Jun 2023.

Sallam M.. The utility of ChatGPT as an example of large language models in healthcare education, research and practice: Systematic review on the future perspectives and potential limitations. 2023. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/

Atlas S. ChatGPT for higher education and professional development: A guide to conversational AI. 2023. from https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/cba_facpubs/548. Accessed 23 Oct 2024.

Hu K. ChatGPT sets record for fastest-growing user base—analyst note. Reuters. 2023. https://www.reuters.com/technology/chatgpt-sets-record-fastestgrowing-user-base-analyst-note-2023-02-01/

Wilson EJ. The information revolution and developing countries. MIT Press; 2006.

Lopez C, Jose R, Rogy M. Enabling the digital revolution in Sub-Saharan Africa: What role for policy reforms? AFCW3 Economic update. Washington: World Bank Group; 2017.

Khalil M, Er E. Will ChatGPT get you caught? Rethinking of plagiarism detection. Preprint arXiv, 2302.04335. 2023. 1–13. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2302.04335

Jones BD, Carter D. Relationships between students course perceptions, engagement, and learning. Soc Psychol Educ. 2019;22(4):819–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-019-09500-x.

Muenks K, Canning EA, LaCosse J, Green DJ, Zirkel S, Garcia JA, Murphy MC. Does my professor think my ability can change? Students perceptions of their STEM professors mindset beliefs predict their psychological vulnerability, engagement, and performance in class. J Exp Psychol. 2020;149(11):19–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000763.

OECD. Understanding the digital divide OECD Digital Economy Papers, No 49. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2001. https://doi.org/10.1787/236405667766.

Vassilakopoulou P, Hustad E. Bridging digital divides: a literature review and research agenda for information systems research. Inf Syst Front. 2023;25:955–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-020-10096-3.

Heeks R. Digital inequality beyond the digital divide: conceptualizing diverse digital incorporation in the global south. Inf Technol Dev. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2022.2068492.

van Dijk J. The digital divide. J Am Soc Inf Sci. 2020;72(1):136–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24355.

Arun C. AI and the global south: Designing for other worlds. Draft chapter for the Oxford Handbook of Ethics of AI. 2019. from https://ssrn.com/abstract=3403010. Accessed 15 May 2023.

Adarkwa MA. “I’m not against online teaching, but what about us?”: ICT in Ghana post Covid-19. Educ Inf Technol. 2021;26:1665–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10331-z.

Buchele FS, Owusu-Aning R. The one laptop per child (OLPC) project and its applicability to Ghana. Sponsored by the U.S. Department of State under a Fulbright Scholar Program grant. 2007. https://archives.ashesi.edu.gh/V3_2004_2010/RESEARCH/RESEARCH/BUCHELE/Buchele_ICAST_OLPC.pdf. Accessed 2 Sept 2023.

Owusu-Ansah S, Bubuame, CK. Accessing academic library services by distance learners. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal), 1347. 2015. from https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3663&context=libphilprac. Accessed 11 Mar 2023.

Langthaler M, Bazafkan H. (2020). Digitalization, education, and skills development in the global South: An assessment of the debate with a focus on Sub-Saharan Africa. ÖFSE Briefing Paper, No. 28, Austrian Foundation for Development Research (ÖFSE), Vienna. 2020.

Körber M. Socio-ethical notes on digitalization—education—global Justice. ZEP - J Int Educ Res Dev Educ. 2018;41(3):13–7.

Banga K, te Velde DW. Digitalization and the future of African manufacturing. Supporting Economic Transformation. 2018. Accessed on June 1 2023 from https://set.odi.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/SET_Future-of-manufacturing_Brief_Final.pdf

Faloye ST, Ajayi N. Understanding the impact of the digital divide on South African students in higher educational institutions. Afr J Sci Technol Innov Dev. 2022;14(7):1734–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/20421338.2021.1983118.

Naudé W. Entrepreneurship, education and the fourth industrial revolution in Africa. Discussion Paper Series. 2017. https://docs.iza.org/dp10855.pdf

The World Bank Annual Report (2016). from https://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/596391540568499043/worldbankannualreport2016.pdf. Accessed 15 Sept 2023.

Jaldi A. Artificial intelligence revolution in Africa: Economic opportunities and legal challenges. Policy Paper, Policy Center for the New South. 2023. https://www.policycenter.ma/sites/default/files/2023-07/PP_13-23%20%28Jaldi%20%29.pdf. Accessed 20 Oct 2023.

Khan B, Fatima H, Qureshi A, Kumar S, Hanan A, Hussain J, Abdullah S. Drawbacks of artificial intelligence and their potential solutions in the healthcare sector. Biomed Mater Devices. 2023;8:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44174-023-00063-2.

Okolo CT, Dell N, Vashistha, A. Making AI explainable in the Global South: a systematic review. In: ACM SIGCAS/SIGCHI Conference on Computing and Sustainable Societies (COMPASS). 2022. pp. 439–452. https://doi.org/10.1145/3530190.3534802

Reiss MJ. The use of AI in education: practicalities and ethical considerations. London Rev Educ. 2021;19(5):1–14. https://doi.org/10.14324/LRE.19.1.5.

Woithe J, Filipec O.. Understanding the adoption, perception, and learning impact of ChatGPT in higher education: A qualitative exploratory case study analyzing students’ perspectives and experiences with the AI-based large language model. 2023. from https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1762617/FULLTEXT01.pdf. Accessed 10 Jul 2023.

Cano YM, Venuti F, Martinez RH. Chatgpt and AI text generators: Should academia adapt or resist. Harvard Business Publishing Education. 2023. fromhttps://hbsp.harvard.edu/inspiring-minds/chatgpt-and-ai-text-generators-should-academia-adapt-or-resist. Accessed 7 Apr 2023.

Ryan M, Antoniou J, Brooks L, Jiya T, Macnish K, Stahl B. The ethical balance of using smart information systems for promoting the United Nations’ sustainable development goals. Sustainability. 2020;12(12):4826. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124826.

Wakunuma K, Jiya T, Aliyu S. Socio-ethical implications of using AI in accelerating SDG3 in least developed countries. J Responsib Technol. 2020;4:100006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrt.2020.100006.

Baidoo-Anu D, Owusu Ansah L. Education in the era of generative artificial intellegnce (AI): understaning the potential benfits of ChatGPT in promoting teaching and learning. J AI. 2023;7(1):52–62. https://doi.org/10.61969/jai.1337500.

Gozalo-Brizuela R, Garrido-Merchan EC. ChatGPT is not all you need. A state of the art review of large generative AI models. 2023. from https://arxiv.org/abs/2301.04655. Accessed 8 Apr 2023.

Helberger N, Diakopoulos N. The European AI act and how it matters for research into AI in media and journalism. Digit J. 2023;11(9):1751–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2022.2082505.

Adiguzel T, Kaya MH, Cansu FK. Revolutionizing education with AI: exploring the transformative potential of ChatGPT. Contemp Educ Technol. 2023;15(3):429. https://doi.org/10.30935/cedtech/13152.

Su J, Yang W. Unlocking the power of ChatGPT: a framework for applying generative AI in education. ECNU Rev Educ. 2023;6(3):355–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/20965311231168423.

Rudolph J, Tan S, Tan S. ChatGPT: Bullshit spewer or the end of traditional assessments in higher education? J Appl Learn Teach. 2023;6(1):342–263. https://doi.org/10.37074/jalt.2023.6.1.9.

Cotton RED, Cotton AP, Shipway JR. Chatting and cheating: ensuring academic integrity in the era of ChatGPT. Innov Educ Teach Int. 2023;1:12. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2023.2190148.

Gilson A, Safranek CW, Huang T, Socrates V, Chi L, Taylor RA, Chartash D. How does ChatGPT perform on the United States medical licensing examination? The implications of large language models for medical education and knowledge assessment. JMIR Med Educ. 2023;9: e45312. https://doi.org/10.2196/45312.

Lund BD, Wang T. Chatting about ChatGPT: how may AI and ChatGPT impact academia and libraries? Library Hi Tech News. 2023;40(3):26–9. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHTN-01-2023-0009.

Perkins M. Academic integrity considerations of AI large language models in the post-pandemic era: ChatGPT and beyond. J Univ Teach Learn Pract. 2023. https://doi.org/10.53761/1.20.02.07.

Zhai X. ChatGPT user experience: implications for education. SSRN. 2022. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4312418.

Dowling M, Lucey B. ChatGPT for (Finance) research: the Bananarama conjecture. Financ Res Lett. 2023;53(1):103662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2023.103662.

Cao Y, Zhai J. Bridging the gap–the impact of ChatGPT on financial research. J Chin Econ Bus Stud. 2023;21(2):177–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/14765284.2023.2212434.

Susnjak T. ChatGPT: The end of online exam integrity? 2023. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2212.09292

Ventayen JRM. ChatGPT by OpenAI: students’ viewpoint on cheating using artificial intelligence-based application. SSRN. 2023. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4361548.

Kasneci E, Sessler K, Kuchemann S, Kasneci G. ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learn Individ Differ. 2023;103:102274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2023.102274.

Qadir J. Engineering education in the era of ChatGPT: Promise and pitfalls of generative AI for education. 2022. https://doi.org/10.36227/techrxiv.21789434.v1

Carden J, Jones RJ, Passmore J. defining self-awareness in the context of adult development: a systematic literature review. J Manag Educ. 2022;46(1):140–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562921990065.

Morin A. Self-awareness Part 1: definition, measures, effects, functions and antecedents. Soc Pers Psychol Compass. 2011;5(10):807–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00387.x.

McGee RW. Is ChatGPT biased against conservatives? An empirical study. SSRN. 2023;3:5. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4359405.

Jowarder M, I. The influence of ChatGPT on social science students: Insights drawn from undergraduate students in the United States. Indonesian J Innov Appl Sci. 2023;3(2):194–200. https://doi.org/10.47540/ijias.v3i2.878.

Cui D, Wu F. The influence of media use on public perceptions of artificial intelligence in China: evidence from an online survey. Inf Dev. 2021;37(1):45–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266666919893411.

Demaidi MN. Artificial intelligence national strategy in a developing country. AI Soc. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-023-01779-x.

Makeleni S, Mutongoza BH, Linake MA. Language education and artificial intelligence: an exploration of challenges confronting academics in global south universities. J Cult Values Educ. 2023;6(2):158–71. https://doi.org/10.46303/jcve.2023.14.

Fiialka S, Kornieva Z, Honcharuk T. ChatGPT in Ukrainian education: problems and prospects. Int J Emerg Technol Learn (IJET). 2023;18(17):236–50. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v18i17.42215.

Popenici SAD, Kerr S. Exploring the impact of artificial intelligence on teaching and learning in higher education. Res Pract Technol Enhanc Learn. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41039-017-0062-8.

Perin D, Lauterbach M. Assessing text-based writing of low-skilled college students. Int J Artif Intell Educ. 2018;28(1):56–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-016-0122-z.

Seo K, Tang J, Roll I, Fels S, Yoon D. The impact of artificial intelligence on learner-instructor interaction in online learning. Int J Educ Technol High Educ. 2021;18(1):54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-021-00292-9.

Brauner P, Hick A, Philipsen R, Ziefle M. What does the public think about artificial intelligence? A criticality map to understand bias in the public perception of AI. Front Comput Sci. 2023. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomp.2023.1113903.

Samuel G, Diedericks H, Derrick G. Population health AI researchers’ perceptions of the public portrayal of AI: a pilot study. Public Underst Sci. 2021;30(2):196–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662520965490.

Wang S. Factors related to user perceptions of artificial intelligence (AI)-based content moderation on social media. Comput Human Behav. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.107971.

Gerlich M. Perceptions and acceptance of artificial intelligence: a multi-dimensional study. Soc Sci. 2023. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090502.

Yeh SC, Wu AW, Yu HC, Wu HC, Kuo YP, Chen PX. Public perception of artificial intelligence and its connections to the sustainable development goals. Sustainability. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169165.

Yigitcanlar T, Degirmenci K, Inkinen T. Drivers behind the public perception of artificial intelligence: insights from major Australian cities. AI Soc. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01566-0.

Miro Catalina QM, Fuster-Casanovas A, Vidal-Alaball J, Escalé-Besa A, Marin-Gomez FX, Femenia J, Solé-Casals J. Knowledge and perception of primary care healthcare professionals on the use of artificial intelligence as a healthcare tool. Digit Health. 2023;9:20552076231180510. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076231180511.

Batubara HH. Penggunaan google form sebagai alat penilaian kinerja dosen di prodi pgmi uniska muhammad Arsyad Al Banjari. Al-bidayah J Pendidik Dasar Islam. 2016;8(1):40–50. https://doi.org/10.14421/al-bidayah.v8i1.91.

Bandalos DL, Finney SJ. Factor analysis: exploratory and confirmatory. In: Hancock GR, Stapleton LM, Mueller RO, editors. The reviewer’s guide to quantitative methods in the social sciences. Milton Park: Routledge; 2018. p. 98–122. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315755649.

Hutcheson GD, Sofroniou N. The multivariate social scientist: introductory statistics using generalised linear models. Newcastle upon Tyne: Sage; 1999.

Stevens J. Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences. 2nd ed. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.; 1992.

Watkins MW. Monte Carlo PCA for parallel analysis [Programa informático]. State College: Ed and Psych Associates; 2000.

Pallant J. SPSS survival manual. 4th ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2010.

Alavi M, Visentin CD, Thapa KD, Hunt GE, Watson R, Cleary M. Chi-square for model fit in confirmatory factor analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2020;76(9):2209–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14399.

Schumacker RE, Lomax RG. A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling. 2nd ed. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2004.

Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999;6(1–55):1210. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE. Multivariate data analysis. 7th ed. London: Pearson; 2010.

Field A. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. 4th ed. Newcastle upon Tyne: Sage; 2023.

Gallagher MW, Brown TA. Introduction to confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation modeling. In: Teo T, editor. Handbook of quantitative methods for educational research. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers; 2013. p. 289–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6209-404-8_14.

Kendal NS, Lamb NK, Henson KR. Making meaning out of MANOVA: the need for multivariate post hoc testing in gifted education research. Gifted Child Quart. 2020;64(1):41–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986219890352.

Adzifome NS, Agyei DD. Learning with mobile devices—insights from a university setting in Ghana. Educ Inf Technol. 2023;28:3381–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11300-4.

Bansah AK, Agyei DD. Perceived convenience, usefulness, effectiveness and user acceptance of information technology: evaluating students’ experiences of a learning management system. Technol Pedagog Educ. 2022;31(4):431–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2022.2027267s.

Ross B, Chase AM, Robbie D, Oates G, Absalom Y. Adaptive quizzes to increase motivation, engagement and learning outcomes in a first-year accounting unit. Int J Educ Technol High Educ. 2018;15(30):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-018-0113-2.

Johnston H, Well FR, Shanks EM, Boey T, Parsons BN. Student perspectives on the use of generative artificial intelligence technologies in higher education. Int J Educ Integr. 2024;20(2):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-024-00149-4.

Bai L, Liu X, Su J. ChatGPT: the cognitive effects on learning and memory. Brian-X. 2023;1(3): e30. https://doi.org/10.1002/brx2.30.

DeLuca C, Coombs A, LaPointe-McEwan D. Assessment mindset: exploring the relationship between teacher mindset and approaches to classroom assessment. Stud Educ Eval. 2019;61:159–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2019.03.012.

Albayati H. Investigating undergraduate students’ perceptions and awareness of using ChatGPT as a regular assistance tool: a user acceptance perspective study. Comput Educ Artif Intell. 2024;6:100203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2024.100203.

Singh H, Tayarani-Najaran M-H, Yaqoob M. Exploring computer science students’ perception of ChatGPT in higher education: a descriptive and correlation study. Educ Sci. 2023;13(9):1–23. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090924.

Acknowledgements

We express our appreciation to all participants from the tertiary institutions in Ghana for their support during the data collection phase.

Funding

There was no funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (DBA, DA, IA, and IM) collaborated on every aspect of this study. DBA, IA, and IM took the lead in conceptualizing and planning the study, as well as in collecting data. DA and IM were involved in developing the introduction and literature review. DBA and DA were responsible for the methodology, conducted statistical analysis, and interpreted the results. The conclusions and implications were largely led by DBA, DA, and IA. All authors (DBA, DA, IA, and IM) approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research was ethically approved by the institutional review boards (IRBs) of the University of Education, Winneba and Atebubu College of Education. Prior to participation, all participants were duly informed of their rights and responsibilities and provided explicit written consent. The study was conducted in agreement with the guidelines governing research involving human participants, as outlined by the respective IRBs of both institutions.

Competing interests

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baidoo-Anu, D., Asamoah, D., Amoako, I. et al. Exploring student perspectives on generative artificial intelligence in higher education learning. Discov Educ 3, 98 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-024-00173-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-024-00173-z