Abstract

Objective

Few studies have investigated the maintenance of skills acquired in classroom-based clinician education. Using an advanced simulation-based clinical communication skill training program for postgraduate psychiatry education (ComPsych), we aimed to investigate skill acquisition through assessing changes in competence (abilities) and performance (practice).

Methods

Forty trainee psychiatrists (15 males; age range 26–48) participated. Video-recorded Standardized Patient Assessments (SPAs) were delivered twice pre- and post-training to assess learning. Skills were coded by independent psychologists using the Core Communication Skills (CCS) coding system. Simulated patients (SPs) rated trainees' communication performance using the Sim-Patient SPA checklist. Paired t-tests, linear mixed models and logistic mixed models assessed changes in communication skills over time.

Results

For SPAs, reliability of coder ratings was deemed acceptable (ICC range 0.67 to 0.87). Mean post-training communication performance significantly increased for skills in agenda setting (p < 0.001), information organization (p < 0.001), empathic skills (p = 0.046), and overall skills performance (p = 0.001). Significant decreases for questioning skills were indicative of reduced reliance on these skills post-training. SPs rated all skillsets higher post-training. A modest relationship was detected between frequency (coded) and (SP-rated) quality of communication skills. Improvements in agenda setting and information organisation skills were retained ~ 6 weeks post-training.

Conclusions

Training improved patient-centered communication skills in psychiatry trainees, particularly skills in agenda setting and information organization, with skills retained ~ 6 weeks post-training. There was reduced reliance on questioning skills, which are well utilised generally. The study supports the benefits of this method of communication skills training into postgraduate psychiatry education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Background

Effective communication skills are crucial in psychiatric practice for optimal therapeutic intervention and doctor-patient relationships [1]. In acknowledgement of this, communication skills have been identified as essential competencies for progressing through the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) Fellowship Training Program [2]. While doctor-patient communication may be observed during clinical work and supervision within psychiatry training programs in the context of obtaining histories, performing mental state examinations and conducting discrete types of therapies, specific and focused communication skills training (CST) in postgraduate psychiatry are not commonplace, and there is little evidence in the literature regarding such educational strategies [3].

In Australia, a first-year postgraduate trainee commences a 3-year formal education course that covers the curriculum of the RANZCP, usually attended four hours per week for around 40 weeks of the year. These sessions are often didactic with some interactivity. There are multiple providers of formal education courses in each state of Australia. Other learning comes in the form of the ‘apprenticeship model’ [4], which entails on-the-job training with supervision by a consultant psychiatrist.

ComPsych is the only CST program delivered in Australia as part of the RANZCP formal education course for Hunter New England (New South Wales) psychiatry trainees. This training is provided early in training (first year) before clinical communication styles and habits are more deeply embedded. Providing additional activities such as CST for trainees can conflict with clinical responsibilities, and Services and trainees may be limited by the costs involved. This formal education course is supported by the health service and delivered at no cost to trainees, and is facilitated in-kind by dedicated senior staff including consultant psychiatrists and psychologists. The CST course is embedded within the first-year curriculum, with no additional time required of trainees outside of expected weekly training attendance. This addresses the common challenge faced by trainees who may otherwise be asked to take time away from clinical work to attend additional training. Those trainees who cannot attend training because they are on leave or other reasons are re-offered the program in subsequent years.

ComPsych was developed to address the significant gap in integrated CST in postgraduate psychiatry education [5,6,7]. The training was piloted within an existing postgraduate training program in a regional Mental Health Service in NSW, Australia [7,8,9]. The program aims to enhance clinicians’ interpersonal communication through a communication framework adaptable to the clinical context. Trainees closely involved with patient care are best placed to immediately transfer the communications skills acquired in training to the workplace, allowing them to develop their skills in practice.

ComPsych scenarios focus on communication skills pertinent to the care of people with major mental illness (schizophrenia). This emphasis is primarily because schizophrenia is encountered frequently within specialist mental health services and presents a more challenging array of communication tasks than other mental health problems [10,11,12]. Previous studies undertaken in the development of the ComPsych model and examinations of its feasibility have highlighted the needs and challenges of people with schizophrenia and their families [6, 8, 9, 13,14,15]. However, despite the focus of the training context being delivered through a lens of communication about schizophrenia, there is potential for the program’s transferability to other mental health conditions and contexts.

Since the original pilot study [8], the ComPsych program has undergone a significant expansion, with the addition of two modules, along with other minor adjustments to actor training, facilitator training, and program delivery timing. For this study, the ComPsych program structure comprised four 2.5–3.0 h modules: Discussing a Diagnosis of Schizophrenia; Discussing Prognosis with People with Schizophrenia; Discussing Treatment and Management of Schizophrenia; and Conducting a Family Meeting. Each module commenced with an introduction to the topic, background evidence regarding the communication needs in this context, and the educational framework, providing an overview of communication goals, strategies, skills, and process tasks, along with specific examples of preferred communication. For instance, Agenda setting, an advanced skill not universally covered in all CST programs, was highlighted. Once acquired, it serves as a powerful organizing tool for directing and redirecting a meeting within a specified time frame [16]. Agenda setting incorporates both the clinician’s desired topics and those of interest to the patient and/or family. Many clinicians find that agenda setting enhances their engagement with patients and families, reducing the frequency of information-eliciting questioning [8].

The approach was aligned to a recovery-orientated framework to foster hope and rehabilitation during conversations. Each trainee received learning materials containing current best-evidence practices. Topic introductions were followed by facilitated small group role-play sessions (2–3 groups with a maximum of five trainees per group) to practice skills with a specially trained simulated patient (SP) for the first three modules, and a ‘family’ of four SPs in a fishbowl format for the module Conducting a family meeting. Role-plays were video-recorded, and trainees received feedback from a trained facilitator and their peers. Details of how the simulated patients were trained, and results of their applicability to the CST were reported previously [17]. Each SPA was conducted with differing scenarios, which tested the same communication skills, but used a developing case to avoid practice effects. The scenarios used for the SPAs were different to the scenarios used for the training role plays.

A well-established oncology evaluation framework in healthcare [18,19,20,21] was utilized in the evaluation of ComPsych and comprises four levels of evaluation [22]. The initial level assesses learner satisfaction and program reaction. Findings for level 1 evaluation of ComPsych have been published previously [9]. A Level 2 pilot study gauging learning outcomes resulting from ComPsych training, encompassing skills, knowledge, or attitude changes has also been published [8]. According to Kissane et al. [22], Level 3 evaluates behavioral changes in the workplace, while the fourth level evaluates program results within its intended context.

While research predominantly indicates increased learner-reported and objectively rated skills acquisition (Levels 1 and 2 of Kirkpatrick’s framework), studies addressing the gap between competence (clinicians' abilities) and performance (actual practice) are scarce. Transfer, extensively studied in applied psychology and management, occurs when newly learned behaviors are applied and sustained in the job context [23, 24]. Factors influencing transfer include training design, delivery, and the work environment [25]. A literature review by van den Eertwegh et al. [26] identified gaps in research on the transfer of communication skills to the clinical workplace. The review suggested a holistic approach to learning, emphasizing not only immediate gains but also long-term workplace interactions. Additionally, it highlighted the need for investigations into factors specific to doctors’ workplace contexts to understand their influence on the transfer of communication skills. This work is being piloted by our group to investigate the transfer of skills to psychiatry trainees’ clinical practice.

In this study, we provide the initial first step in the process of examining transfer by comparing psychiatry trainees’ communication skill ratings from objective blind-coders with those of simulated patients to assess quantity and quality of trainee communication. This work builds on previous research by conducting a robust evaluation of ComPsych communication skills acquisition within the context of standardized learning (Level 2). The objectives included a comparison between SPA coder-rated skill acquisition with that of simulated patient-rated communication skills to assess if skill frequency (as measured by blinded coders) and skill quality (as measured by the SPs) are associated, and whether trainees’ communication performance was retained one month (4–5 weeks) post-training.

2 Materials and methods

This project was approved by the Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee (15/12/16/4.06). All methods were performed in accordance with the ethics guidelines and regulations, and all trainees and simulated patients provided informed written consent to take part in the study. Participation was entirely voluntary and no participation incentives were provided.

The study design involved Standardized Patient Assessments (SPAs) conducted at four intervals throughout the program—twice pre-training and twice post-training—allowing for a robust blind-coded evaluation of the progression of skill frequency and acquisition over time. SPs also rated individual trainee skills, with a particular emphasis on communication skill quality, permitting an investigation of whether a relationship exists between skill frequency (as measured by blinded coders) and perceived skill quality (as measured by the SPs).

2.1 Participants

Participants included 40 psychiatrists in training (15 males), aged between 26 and 48 years (M = 32.4, SD = 5.6), with 1–3 years of psychiatry training experience (year 1 = 67.5%; year 2 = 25%, year 3 = 7.5%). Participants who did not undertake training in their first year were offered the opportunity to undertake the training in subsequent years. Participants in the study attended at least one SPA and at least one module of the ComPsych CST program (2015–2018) through the HNET formal education course in NSW, Australia. The majority of participants (80%) completed at least three modules of the training.

2.2 Procedure

Skill acquisition was assessed through video recordings of 15-min SPAs, collected at two time points pre-training (~ 6 weeks before training and immediately before the first session) and two time points post-training (immediately after the final training module, and the last collected ~ 6 weeks later). Each SPA presented a different case scenario from that of training, to mitigate practice effects.

2.3 Coding

Two independent coders were trained and employed to review 133 video-recorded SPAs. The coders were not affiliated with the ComPsych research team but possessed expert backgrounds in communication (psychologists). Batches were randomly numbered on a Universal Serial Bus. Coders received training in the scoring method, a coding manual, and practiced coding communication skills with the trainer. Extensive discussions were held to clarify any areas of uncertainty. The coders were kept blind to the study design, order of interviews, and whether recordings were pre- or post-training. Coders utilized a validated instrument, the Core Communication Skills coding sheet from the ComSkil Coding System (CCS) [27] to assess the frequency of 20 specific communication skills (presented in Table 2).

SPs were trained and standardized across all case scenarios, were provided with a training manual, and practiced each case scenario with the trainer pre-sessions. The same SPs participated across all 133 video-recorded SPAs, gaining significant experience. At the end of each SPA, SPs rated each trainee they interacted with for quality of communication using the Sim-Patient SPA Checklist [27], consisting of 17 items rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). These items were directly related to the skillsets outlined in the CCS.

2.4 Data analysis

Reliability was assessed for the two coders for each skillset total of the CCS using intra-class correlation (ICC) statistics (two-way mixed model, absolute agreement, average measures). An ICC of 0.6 or above (considered good/excellent, following Cicchetti and Sparrow [28]), justified the averaging the coders’ scores.

For the analysis of coding sheets, individual skills frequencies, skillset total frequencies, and overall total CCS frequencies for four SPAs were measured and reported. Differences in pooled pre-training (SPAs 1 and 2) and post-training (SPAs 3 and 4) averages for each skill and skillset total were analyzed using paired t-tests. Changes over time (four SPAs) for each skillset total (Agenda Setting; Checking; Questioning; Information Organization; and Empathic skills) were analyzed in a linear mixed model (REML estimation method) with a fixed effect for SPA Number and Participant as the random intercept to account for correlation within participants over Time, along with the overall effect for Time. Differences calculated using the linear mixed modelling between SPA 1 versus 2, 2 versus 3, and 3 versus 4 are presented. The models accounted for missing data if participants had data for at least one SPA. Characteristics of age, gender, and year of psychiatry training were analyzed in linear regression models for each skillset to check whether these characteristics were significantly associated with scores.

Ratings of trainees’ communication skills from the Sim-Patient SPA checklist (on a 5-point Likert-type scale) provided by SPs were transformed to dichotomous variables, indicating whether the SP agreed or strongly agreed that the trainee performed each task (Yes) or not (No). Changes in the proportion of ‘Yes’ for each item were analyzed across SPAs using binary logistic mixed models with a fixed effect of SPA number and random intercept of Participant to account for correlation within the participant over time. Pre/post comparisons of the mean total score of the 5-point Likert-type scale for all combined items as well as item skillsets were analyzed using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, considering the non-normality of ordinal scale data. A Spearman correlation analysis between the mean total SP ratings of trainees’ communication skills quality and the mean total coder-rated frequencies of communication skills was performed.

Analyses were conducted using SPSS software [29] and SAS [30]. A priori, p < 0.05 (two-tailed) was used to indicate statistical significance.

3 Results

3.1 Reliability

Reliability was considered acceptable, as shown in Table 1. Consequently, the data was pooled, and the mean of the two coders was analyzed. Reliability was also verified across each SPA individually, and similar conclusions were drawn.

3.2 Core communication skills

Individual skills frequencies, skillset total frequencies, and overall total skills frequencies were assessed (see Table 2). Post-training the mean communication performance was significantly higher for the skillsets of agenda setting (p < 0.001), information organization (p < 0.001) and empathic skills (p = 0.046), as well as for overall skills performance (p = 0.001). No skillsets showed a significant decrease in this post-training assessment.

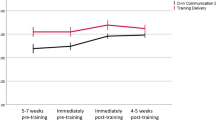

Changes over time were monitored across SPAs 1, 2, 3 and 4 for all skillsets (see Fig. 1). In all linear mixed models, residual plots did not reveal any obvious deviations from homogeneity of variances or normality.

3.2.1 Agenda setting skills

The test of the fixed effect of Time (SPA Number) in the linear mixed model was significant for the Agenda Setting skillset, F (3,90) = 22.5, p < 0.001. This indicates a clear uptake of Agenda Setting skills after training, which were retained at SPA 4 (~ 6 weeks post-training). Pairwise comparisons revealed a significant difference between SPA 2 (M = 1.21, SE = 0.19) and SPA 3 (M = 2.86, SE = 0.23), t(90) = − 6.23, 95%CI [− 2.18, − 1.13], p < 0.001, representing the period during which the training intervention occurred.

3.2.2 Checking skills

The test of the fixed effect of Time (SPA Number) was significant for the Checking skillset, F (3,90) = 8.62, p < 0.001, indicating significant changes across SPAs for Checking skills. Pairwise comparisons showed a significant decrease between SPA 1 (M = 1.82, SE = 0.26) and SPA 2 (M = 0.76, SE = 0.13), t(90) = − 4.16, 95%CI [− 1.57, − 0.55], p < 0.001, which occurred before the training intervention. There was no significant increase after training.

3.2.3 Questioning skills

The test of the fixed effect of Time (SPA Number) was significant for the Questioning skillset, F (3,90) = 4.50, p = 0.005, suggesting significant changes across SPAs for Questioning skills. Pairwise comparisons revealed a significant decrease between SPA 3 (M = 7.27, SE = 0.46) and SPA 4 (M = 5.85, SE = 0.44), t(90) = 2.94, 95%CI [0.46, 2.38], p = 0.004, following the training intervention. Questioning skills were performed at a high level and remained steady across the first three SPAs, then experienced a decline between SPA 3 and 4.

3.2.4 Information organization skills

The test of the fixed effect of Time (SPA Number) was significant for the Information Organization skillset, F (3,90) = 12.02, p < 0.001, indicating significant changes across SPAs for Information Organization skills. Pairwise comparisons showed a significant difference between SPA 2 (M = 1.08, SE = 0.15) and SPA 3 (M = 2.30, SE = 0.29), t(90) = − 4.2, 95%CI [− 1.80, − 0.64], p < 0.001, during which the training intervention occurred. There was a significant uptake of Information Organization skills immediately after training, which was retained through to SPA 4, with a slight but not significant decay.

3.2.5 Empathic skills

In the acquisition phase, the test of the fixed effect of Time (SPA Number) was significant for the Empathic skillset, F (3,90) = 3.05, p = 0.03, indicating significant changes across SPAs for Empathic skills. Pairwise comparisons revealed only a marginal difference between SPA 1 (M = 5.50, SE = 0.40) and SPA 2 (M = 4.30, SE = 0.48), t(90) = − 2.01, 95%CI [− 2.37, − 0.01], p = 0.048, before the training intervention. There was also a significant difference between SPA 2 and SPA 3 (M = 5.79, SE = 0.57), t(90) = − 2.33, 95%CI [− 2.76, − 0.22], p = 0.02, during the training intervention. Empathic skills were initially performed at a high level, with a slight decline between the first two SPAs. However, skills returned to baseline levels immediately after training and were retained through to SPA 4.

Separate linear regression analyses were conducted for each skillset to examine the relationship between the mean score for each skillset and various characteristics. Dose of training ranged from trainees having attended 1 to 4 modules (1 module = 2; 2 modules = 6; 3 modules = 9; 4 modules = 23). For the Checking skillset, age was significantly associated with score (p = 0.023), with the model showing that for each year of increase in age, Checking skills increased on average 0.46. For the Empathic skillset, age was also significantly associated with skillset score (p < 0.001), with the model showing that for each year of increase in age, Empathic skills decreased on average -0.17. For the Information Organization skillset, gender was significantly associated with score (p = 0.025), with the model showing that females’ Information Organization skills decreased on average -0.592 in comparison to males. None of the other characteristics tested in the remaining regression models (including Dose) were significant predictors of score for skillsets. For each linear regression model, assumptions (including linearity, multicollinearity, independence, and normal distribution of the residuals) were checked and no anomalies were detected.

3.3 Simulated patient ratings of trainee communication

The statistical tests for SP-rated changes over time (SPA; see Table 3) revealed significant differences among SPAs for Items 4, 6, 12, 14 and 17. Seven items did not converge, and the significance of the model could not be calculated for those items.

In pre/post comparisons of simulated patient ratings, SPs rated all skillsets higher post-training compared to pre-training (see Table 4).

3.4 Quantity versus quality of skills

Lastly, a Spearman correlation analysis between the mean total SP ratings of trainees’ communication skills quality (from the Sim-Patient SPA Checklist) and the mean total coder-rated frequencies of communication skills (from the Core Communication Skills coding sheet) revealed a small-moderate, statistically significant relationship between the ratings (rho[131] = 0.212, p = 0.015), explaining 4.4% of the variability of these measures (see Fig. 2). As coder-rated CCS scores increased, so did SP ratings of the quality of communication skills.

4 Discussion

This study compared the communication frequency and quality of postgraduate psychiatry trainees post-ComPsych training and over time. Increases in performance were observed for agenda setting, information organization, and empathic skills. SPs rated the quality of all performed skillsets higher post-training, and a correlation was found between the coded quantity of skills performed and the SP-rated quality of skills performed.

Regarding the pattern of specific skillset changes, agenda setting skills notably improved following training and were retained ~ 6 weeks later. Checking skills, while showing no clear pre- to post-training change, significantly dropped between the first and second measurements before training, impacting the overall pattern of acquisition for this skillset. We were unable to predict the factors that may have influenced this pattern, which could include environmental factors, participant characteristics, or variations in training procedure that affected this skillset but not others. Further training or ‘booster’ sessions may be required to foster an increase in checking skills. No significant pre- to post-training changes were observed in Questioning skills, but they decayed between post-training measurements. The reduction in Questioning skills suggests a potential shift in usage, possibly due to increased reliance on agenda setting and information organization skillsets. The post-training decrease in Questioning skills was not significant and mirrors results from the original pilot study [8]. The suggestion that trainees may be performing certain skill sets at the expense of others, and which skills are most important, is a vital area to explore in future work. This skill usage attenuation (i.e., that some skills may degrade as others are used with more frequency) has the potential to alter current accepted practice in CST.

Information Organization skills exhibited a clear uptake after training. Empathic skills, although showing an overall increase from pre- to post-training, were challenging to interpret due to a significant decrease between pre-training measurements. However, it is noteworthy that both baseline and post-training means for Questioning and Empathic skills were far higher than other skillsets, indicating a reasonable grasp of these skills by trainees. The lack of significant movement in these skills suggests that trainees used them more frequently than other skillsets.

For empathic skills, the findings suggest that younger trainees performed better. This may point to the previously identified changes in empathy, reported in longitudinal research among medical students [31]. However, despite age as a factor, all participants were working as junior doctors. Without comparators, it is not possible to confirm this effect. It would be useful to investigate this further in future research.

The regression models also identified that Information Organization skills decreased in females compared to males. One possibility is that female trainees became less reliant on Information Organization as a skill over time or began using a less formal skill to organize information. Evidence shows that males and females differ in their communication style and behaviours, including the length of time taken in consultations [32,33,34,35]. This is an interesting finding worthy of further investigation in future research to examine the gender differences in communication styles by trainees with patients.

The inclusion of SP ratings of the quality of trainees’ communication performance provided a unique perspective from the person receiving the communication. Although SPs were not blinded to the timing of the SPAs, their ratings were significantly correlated with the blinded coders’ ratings, adding validity to the SP ratings. The relationship between frequency of communication skills performed and the graded rating from the SPs suggests that the quality of performance, as perceived by the (simulated) patient, is associated with frequency.

While research predominantly indicates increased learner-reported and objectively rated skills acquisition (Levels 1 and 2 of Kirkpatrick’s framework), studies addressing the gap between competence (clinicians’ abilities) and performance (actual practice) are scarce. Transfer, extensively studied in applied psychology and management, occurs when newly learned behaviors are applied and sustained in the job context [23, 24]. Factors influencing transfer include training design, delivery, and the work environment [25]. A literature review by van den Eertwegh et al. [26] identified gaps in research on the transfer of communication skills to the clinical workplace. The review suggested a holistic approach to learning, emphasizing not only immediate gains but also long-term workplace interactions. Additionally, it highlighted the need for investigations into factors specific to doctors’ workplaces to understand their influence on the transfer of communication skills. A study to investigate the transfer of skills to psychiatry trainees’ clinical practice is the next step for further research.

It is acknowledged that this training sits alongside teaching and supervision in psychotherapies that also emphasize the importance of the therapeutic alliance and clinician-patient relationship [36, 37]. ComPsych differs in that it provides more focused and structured attention to particular tasks in the clinical encounter and uses methods not applied to motivational interviewing or psychotherapy training, but recognise that these skills intersect with other aspects of those frameworks.

Findings from this study are limited by the absence of a control group. While future research should consider utilizing randomised controlled trials, it is important to acknowledge the difficulties of achieving this methodology, including our own method, in a time-limited educational program for post-graduate trainees, where trainees rotate geographically across a large district every 3–6 months. An alternative method could be to compare a trained cohort to a group who does not receive the training. It is also acknowledged that SP ratings are not analogous to real psychiatric patient ratings, and while they provide a useful research tool given their standardized practice and experience, understanding which communication skills are most effective with different patient groups and settings remains a crucial objective of research. Future adaptations of the program could be included to investigate whether actual patients could be used as an alternative to SPs, and to increase the pool of trained local faculty to deliver the curriculum and assessment. Training facilities that lack funding to undertake this training may need to apply for government or other grants to facilitate payments for SPs and other resources.

In conclusion, quantity and quality of communication skills are improved using a simulation-based training program, focussing on common aspects of clinical practice in the care of people with severe mental illness. Comparisons between SPA and SP skill ratings show improvements in a range of patient-centered communication skills among postgraduate trainees in psychiatry, and provide initial first steps in demonstrating competence and performance skill retention and transfer over time. The findings support the integration of CST into postgraduate training programs.

Data availability

Data sets generated during the current study are not openly available, as the data are located in controlled access data storage at the University of Newcastle as SPSS files, but the authors no longer have access to that software. The data may be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Priebe S, Dimic S, Wildgrube C, Jankovic J, Cushing A, McCabe R. Good communication in psychiatry—a conceptual review. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26:403–7.

RANZCP. 2012 Fellowship Program EPA Handbook Stage 1 and 2 [Internet]. 2012. Available from: https://www.ranzcp.org/training-exams-and-assessments/exams-assessments/list-of-epas.

Ditton-Phare P, Loughland C, Duvivier R, Kelly B. Communication skills in the training of psychiatrists: a systematic review of current approaches. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2017;51:675–92.

Clinical Supervision Support Project. Clinical Supervision Support Project: A Framework of Professional Activities for Supervisors [Internet]. RANZCP. [cited 2024 Mar 1]. Available from: https://www.ranzcp.org/getmedia/e47e5165-b871-48c0-b1dc-3771913c9bea/clinical-supervision-support-project-framework.pdf.

Ditton-Phare P, Halpin S, Sandhu H, Kelly B, Vamos M, Outram S, et al. Communication skills in psychiatry training. Australas Psychiatry. 2015;23:429–31.

Levin TT, Kelly BJ, Cohen M, Vamos M, Landa Y, Bylund CL. Case studies in public-sector leadership: using a psychiatry e-list to develop a model for discussing a schizophrenia diagnosis. PS. 2011;62:244–6.

Loughland C, Ditton-Phare P, Kissane DW. Communication and relational skills in medicine. In: Grassi L, Riba MB, Wise T, editors. Person centered approach to recovery in medicine: insights from psychosomatic medicine and consultation-liaison psychiatry. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019. p. 163–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74736-1_9.

Ditton-Phare P, Sandhu H, Kelly B, Kissane D, Loughland C. Pilot evaluation of a communication skills training program for psychiatry residents using standardized patient assessment. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40:768–75.

Loughland C, Kelly B, Ditton-Phare P, Sandhu H, Vamos M, Outram S, et al. Improving clinician competency in communication about schizophrenia: a pilot educational program for psychiatry trainees. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39:160–4.

McCabe R, Priebe S. Communication and psychosis: it’s good to talk, but how? Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:404–5.

Angermeyer MC, Schulze B. Reducing the stigma of schizophrenia: understanding the process and options for interventions. Epidemiol Psychiatric Sci. 2001;10:1–7.

Raffard S, Bayard S, Capdevielle D, Garcia F, Boulenger J-P, Gely-Nargeot M-C. Lack of insight in schizophrenia: a review. Part I: theoretical concept, clinical aspects and Amador’s model]. Encephale. 2008;34:597–605.

Outram S, Harris G, Kelly B, Cohen M, Bylund CL, Landa Y, et al. Contextual barriers to discussing a schizophrenia diagnosis with patients and families: need for leadership and teamwork training in psychiatry. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39:174–80.

Outram S, Harris G, Kelly B, Bylund CL, Cohen M, Landa Y, et al. ‘We didn’t have a clue’: family caregivers’ experiences of the communication of a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2015;61:10–6.

Loughland C, Cheng K, Harris G, Kelly B, Cohen M, Sandhu H, et al. Communication of a schizophrenia diagnosis: a qualitative study of patients’ perspectives. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2015;61:729–34.

Mauksch LB, Dugdale DC, Dodson S, Epstein R. Relationship, communication, and efficiency in the medical encounter: creating a clinical model from a literature review. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1387–95.

Ditton-Phare P, Sandhu H, Kelly B, Loughland C. ComPsych communication skills training: Applicability of simulated patients in psychiatry communication skills training. Australas Psychiatry. 2022;30:552–5.

Bates R. A critical analysis of evaluation practice: the Kirkpatrick model and the principle of beneficence. Eval Program Plann. 2004;27:341–7.

Frye AW, Hemmer PA. Program evaluation models and related theories: AMEE guide no. 67. Med Teach. 2012;34:e288-299.

Kirkpatrick DL. Evaluation of training. In: Bittel LR, Craig RL, editors. Training and development handbook. New York: McGraw Hill; 1967. p. 87–112.

Kirkpatrick D. Great ideas revisited: techniques for evaluating training programs. Training Dev. 1996;50:54.

Kissane D, Bylund C, Banerjee S, Bialer P, Levin T, Maloney E, et al. Communication skills training for oncology professionals. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1242–7.

Blume BD, Ford JK, Baldwin TT, Huang JL. Transfer of training: a meta-analytic review. J Manag. 2010;36:1065–105.

Cheng EWL, Hampson I. Transfer of training: a review and new insights. Int J Manag Rev. 2008;10:327–41.

Burke LA, Hutchins HM. Training transfer: an integrative literature review. Hum Resour Dev Rev. 2007;6:263–96.

van den Eertwegh V, van Dulmen S, van Dalen J, Scherpbier AJJA, van der Vleuten CPM. Learning in context: identifying gaps in research on the transfer of medical communication skills to the clinical workplace. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;90:184–92.

Bylund CL, Brown R, Gueguen JA, Diamond C, Bianculli J, Kissane DW. The implementation and assessment of a comprehensive communication skills training curriculum for oncologists. Psychooncology. 2010;19:583–93.

Cicchetti DV, Sparrow SS. Assessment of adaptive behavior in young children. In: Johnson JH, Goldman J, editors. Developmental assessment in clinical child psychology: a handbook. Elmsford, NY, US: Pergamon Press; 1990. p. 173–96.

IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.; 2011.

SAS Institute Inc. SAS/ACCESS. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 2013.

Hojat M, Vergare MJ, Maxwell K, Brainard G, Herrine SK, Isenberg GA, et al. The devil is in the third year: a longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical school. Acad Med. 2009;84:1182–91.

Roter DL, Hall JA, Aoki Y. Physician gender effects in medical communication—a meta-analytic review. JAMA. 2002;288:756–64.

Mast MS, Kadji KK. How female and male physicians’ communication is perceived differently. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101:1697–701.

Jefferson L, Bloor K, Birks Y, Hewitt C, Bland M. Effect of physicians’ gender on communication and consultation length: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2013;18:242.

Bertakis KD. The influence of gender on the doctor-patient interaction. Patient Educ Counseling. 2009;76:356.

Flückiger C, Del Re AC, Wampold BE, Horvath AO. The alliance in adult psychotherapy: a meta-analytic synthesis. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2018;55:316–40.

Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational interviewing. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:91–111.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank HNET Psychiatry trainees for participating in this study. Thanks to Kerrin Palazzi at HMRI Clinical Research Design and Statistical Services for statistical assistance.

Funding

This research was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship and additional funding assistance from the Center for Brain and Mental Health Research. The funding body of the student’s PhD played no role in study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing the report or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. They accept no responsibility for the contents.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This study was conducted by a PhD student from the University of Newcastle, in conjunction with the student’s supervisors. Conceptualization and methodology was undertaken by all authors. Investigation was undertaken by Philippa Ditton-Phare, who prepared the first draft of the paper and all authors contributed to reviewing and editing the final manuscript. Supervision was provided by Carmel Loughland (primary supervisor), Brian Kelly (secondary supervisor) and Harsimrat Sandhu (secondary supervisor). We would like to thank the Psychiatry trainees who participated in this study. Thanks to Kerrin Palazzi at Hunter Medical Research Institute Clinical Research Design and Statistical Services for statistical assistance.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author(s) declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ditton-Phare, P., Sandhu, H., Kelly, B. et al. Acquisition of key clinical communication skills through simulation-based education: findings from a program for postgraduate psychiatry trainees (ComPsych). Discov Educ 3, 53 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-024-00141-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-024-00141-7