Abstract

Many leaders in medical education have called for the inclusion of students with disabilities. Yet, a small number of review articles have been written summarizing the key literature addressing this topic. This review focuses on literature published between 2000 and 2021 that discusses medical education disability-specific barriers, student disability prevalence, and available institutional disability resources. Barriers include lack of procedure for students with disabilities to access services, delays in education to address disability needs, identified institutional disability resource professional (DRP), structural and physical barriers, outdated policies, and lack of understanding of accommodations needed in all educational settings, especially clinical. Medical school stakeholders must clearly understand the published literature on this topic to promote the full inclusion of students with disabilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

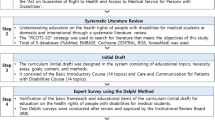

Over the past few decades, many leaders in medical education have called for the full inclusion of students with disabilities [1]. Surprisingly, although many articles have been written, no review has been published in a journal that summarizes this topic's critical literature. This review focuses on literature published in journals between 2000 and 2021 that discuss medical education disability-specific barriers, medical student disability prevalence, and available institutional disability resources. The number of medical students disclosing disabilities to their institutions increased from roughly 2.7% in 2016 to 4.6% in 2019 [2]. Alongside this increase, resources provided to include those with disabilities also need to be enhanced [1, 3]. However, for stakeholders to understand the resources required to support students with disabilities (SWD), they must become familiar with the literature that has been published that enumerates barriers facing this specific population. Therefore, a scoping review was conducted by searching for specific criteria such as disability prevalence, barriers to institutional support programs, lack of understanding of accommodation needs, and the need for more research, all presented in Table 1 using EBSCO host, Google Scholar, Pubmed, and the Coalition for Disability Access in Health Science Education website for papers that specifically address barriers facing SWD. Overall, 30 scholarly papers were identified as published bodies of work on medical students with disabilities; 28 of these papers met the criteria for this scoping review.

Throughout the literature, four common themes were presented: a noticeable increase in the prevalence of students with disabilities in medical education, institutional support program barriers, the need for all who interact with students to understand accommodation needs, and the need for more research to understand best practices to support this population of learners. One main concern is a deficit in model support programs to support learners with disabilities across the medical education spectrum [4]. Barriers have included structural barriers, including restrictive or outdated policies and procedures [1], a poor understanding of clinical accommodations [1], a gap between disability and wellness support services [1], and a physical environment that limits accessibility, often resulting in very immediate, specific, and practical implications for trainees [4].

2 Disability prevalence

Many of the studies within this review discuss medical students with disabilities, yet not all the studies specify disability prevalence (Table 1). In 2012 Eickmeyer and colleagues reported a 0.3 to 0.6% prevalence of North American medical students with disabilities [5]. The U.S. population has been reported to have 19% of persons with sensory disabilities (such as deafness or difficulty seeing). Yet less than 1% of medical students and 2–10% of practicing physicians represent that population [6]. In the past 3–5 years, quantitative data has been collected to demonstrate the rise in students disclosing disabilities in medical education. Meeks et al. 16 reported that between 2016 and 2019, there was an increase in medical student disclosure to their institution from 2.7 to 4.6% overall [1, 2, 5]. The top categories reported were ADHD/DD at 30.4% and psychological disabilities (Adjustment, anxiety, obsessive–compulsive, post-traumatic stress, and bipolar disorder, to name a few) at 32.3% [1, 2, 5]. Learning disabilities, chronic health disorders, physical and sensory disorders make up 18–1% [1, 2, 5]. Some of the students who disclosed also have more than one of the high-profile category disabilities, which is why if one were to add up the percent numbers, there would be a total of over 100% [6]. As attention towards this subject grows more substantial, internal, and national processes are necessary to facilitate reporting medical student disability data, including psychological disabilities [1, 2, 5]. Although an increase in medical students disclosing disabilities has been reported, there are gaps in available information regarding the experiences of these students and their retention in the training and career pipeline [1, 2, 5]. Currently, it is suggested that 1% of medical students disclose major depressive disorder because of structural barriers such as discrimination and judgment [1, 2, 5, 7]. Two-thirds of medical students who disclosed their disability had psychological or learning disabilities [1, 2, 5, 7].

Student’s fear disclosing due to the risk of their confidentiality being exposed, which increases the need to continue reducing stigma and improving support programs around disclosure [1, 2, 5, 7]. Studying the academic performance of medical students with disabilities is new and requires a better understanding of the prevalence of students within various categories of disabilities [1, 5, 8]. Medical schools are required under federal mandate to document any communication and decision-making regarding students with disabilities [2], and yet no centralized system currently exists to track this data nationally. A recent 2021 study by Meeks et al. addressed the lack of information about whether accommodations on USMLE Step 1 impact performance, time to graduation, and match rates. The information discussed in the Searcy and Tehrani articles left the area of students being accommodated within the medical school and on USMLE Step exams open for more investigation [9–11]. Within the study, 69% of students were identified as having cognitive/learning disabilities [9]. Although these students had lower Step 1 scores and were less likely to graduate on time, no accommodated SWD Step 1 scores were lower than the rest of the population. When SWD are accommodated, they perform better than their no accommodated SWD peers, which indicates that barriers remain, and students are not being rightfully accommodated [9].

There are many benefits to increasing the representation of medical students with disabilities, thereby increasing the number of physicians with disabilities. These include the idea of patients feeling more comfortable with a physician who has a disability [4]. One statistical comparison indicated that nondisabled physicians have a disadvantage because they are unable to better understand a patient's feelings who are disabled. One who does understand disability can better empathize—disabled respondents were much more likely to react positively. Increasing meaningful reporting relationships with DRPs for students with disabilities and dedicated disability awareness training is vital for challenging existing beliefs and recognizing individuals with disabilities' full potential to become health care providers [12]. Meeks et al. [13] found that of students who disclosed their disability, 10% had apparent disabilities such as visual, mobility, and auditory disabilities [12]. Students with invisible, less noticeable disabilities, such as attention, learning, psychological, and chronic health disabilities, make up the remaining 90% [12].

3 Barriers to institutional support programs

Numerous articles demonstrate that the social construction of the medical school environment presents considerable barriers for individuals with physical disabilities (Table 1) [4]. Broader advocacy is needed to align the institution's technical standards with an inclusive message [11]. The practice of regularly updating technical standards is likely to address some barriers facing medical students with disabilities [3], including allowing the use of new assistive technologies [5, 14].

Physicians with disabilities are more likely to commit to fostering an accessible and supportive environment for patients [3]. When the population of physicians includes those with hearing loss, this can support patients who experience hearing loss as part of the aging process [1].

Medical school stakeholders can support students and practicing physicians with physical disabilities by using creative approaches to clinical work [13]. Acceptance can be achieved by not promoting ideology but, preferably, making systemic changes to create better opportunities and sustain individuals with disabilities to pursue careers in medicine [13]. From a student services perspective, a collaborative approach that facilitates access to the program normalizes a student with deafness presence and contributes to an inclusive and non-marginalizing experience is exceptionally appropriate in this situation [12].

Students with Learning Disabilities (LD) accounted for 6% of students entering higher education in 2010 [8, 15]. Within a particular group of medical students, a learning disability may be unknown and is only discovered when a student faces barriers as the volume and pace of medical school curricula increases [15]. A study from 2000 revealed that almost 66% of the students surveyed were not aware that they had a learning disability when they entered college [9, 15]. Early recognition of these learning disabilities and proper accommodation can dramatically change these students' learning processes and academic outcomes [15]. The theme of creating a more accessible environment to allow for disclosure can aid in breaking that stigma.

Having routine identification of barriers so there can continue to be creative, appropriate accommodations and plans to continue to make students aware that these supports are in place [15]. This requires that students disclose their disability and related needs to the institution. Within the first year of medical school, self-referral and academic failure have been the most common means of identifying students with learning disabilities [11, 15]. A consistent discrepancy between a student's academic performance and their understanding of the subject matter must be considered a warning sign to probe further [15]. Late diagnosis is further complicated by issues related to intersectionality-socioeconomic and educational backgrounds [14]. Those who work with medical students understand that students may be diagnosed with language and reading disorders following admission to medical school [14]. 2.86% of U.K. medical students disclosed having a disability in 2005 upon matriculating into medical school [8]. Students with impairments such as ADHD and Learning Disabilities may find what they developed as coping strategies ineffective when studying medicine, which lead them to question if their capability and therefore, possibly seeking a diagnosis [7]. Medical students are a population in general often whom do not often seek help, especially those presenting with disabilities, because there remains the fear of being "outed" or ostracized within the medical education system even though they are within their rights to receive the accommodations entitled by federal law [16]. Having medical students become confident in disclosing disabilities can be done by creating safe environments for them to do so. Providing a safe and knowledgeable environment can change students' attitudes and perceptions towards their peers with disabilities. The American association of medical colleges (AAMC) also requested that LCME accredited medical schools employ structures to allow for more disability disclosure [6]. As of now, 35% of North American medical schools do not have environments that support access for students with disabilities [6]. These structural barriers continue for medical students which turns them off from accessing accommodations and therefore deter disability disclosure [6].

In Javaeed [5], it was demonstrated that with proper accommodations for multiple choice question exams, students with learning disabilities could perform at a satisfactory or exceptional level [7]. Javaeed observed two groups of students; those that disclosed their disability and those that did not. According to the article, students who did not disclose had lack of awareness of possible accommodations and an overwhelmingly unfortunate nonpositive view of their disability [7]. Though they seemed self-aware, this awareness was considered "faulty." The students reported that they did not think they needed the accommodations and were apprehensive about avoiding damaging comments/remarks from peers [7].

There was a contrast with the disclosure group compared to the nondisclosure group in that the disclosure group had a more positive view of their disability which made their experience more fruitful [7]. When the non-disclosure students enter medical school, a pattern develops in which the increasing demand for academic coursework overwhelms them, and their performance only continues to worsen. The student's struggle may become a hurtful pattern until the student loses self-esteem and sometimes their mental health can be affected [1].

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in adulthood has been linked to severe functional impairment in various areas of life, including academic underachievement [2, 3, 17]. There is limited data available on the prevalence of ADHD in the higher education student population and more so in medical students. Researchers: Tuttle et al. [18] found that 5.5% of medical students reported being diagnosed with ADHD across all 4 years of education in United States. public medical colleges [1, 16]. Therefore, students with ADHD might struggle applying their previous coping skills which can be ineffective in tackling medical school's demanding curriculum. Studies are starting to be published that highlight disability category, such as ADHD [16]. ADHD remains to make up around 30% of disclosed disabilities by North American medical students, while psychological disabilities have increased from 20 to 32% of disclosed medical students [16]. Along with more prevalence studies being updated and published, the AAMC graduate questionnaire (G.Q.), as of 2020, now reports disabilities of medical students by category.

Stakeholders face a struggle to support a student who does not self-identify, does not receive accommodations, and will not have full access to demonstrate their knowledge [19]. Unfortunately, as students experience stigma, they are less likely to disclose and get the help they require. This culture of lack of support was discussed in Romberg et al. when a faculty member accused a student of using their disability as an excuse to receive special treatment [19].

4 Lack of understanding of accommodation needs

Medical school designees are charged with determining appropriate and reasonable accommodation plans for qualified applicants with disabilities [3]. There are many misconceptions about providing accommodations for medical students; one of the most concerning is that incorporating accommodations into licensure exam environments decreases exam efficacy and presents concerns about ensuring that performance standards are met [20]. The concept of inclusive education orders that schools accommodate all learners in the classroom [15]. An inclusive learning environment allows students to celebrate each other's strengths and support each other as they improve limitations [8, 15]. The inclusive design incorporates the thoughts and principles of universal design for learning (UDL), which places high value on diverse student learning and inclusion of learning differences [8, 16]. However, incorporating inclusive learning, students should still be referred so that their accommodation needs are met [8, 16]. In a 2014 study, medical students with ADHD receiving accommodations reported considerably more prominent symptoms than those not receiving accommodations, indicating that students with the most severe cases of ADHD are receiving support, though few investigations have looked at the efficacy of specific academic accommodations in this population [1]. The 2014 study also confirms other reported findings [21, 22], which suggest that test accommodations, including extra time, allow students with specific learning difficulties and ADHD to perform at the same level as their peers [23].

Testing accommodations are classified as alterations such as extended time, extra breaks, private room, and ability to bring snacks and medications are among some modifications to standard test administration to allow test takers with documented disabilities to show their abilities rather than the extent of their disabilities. Students whose MCAT scores were obtained with extra time accommodations demonstrated no significant difference between these students matriculating into medical school admission than students with standard testing time [6, 24]. However, students who took the MCAT with timed accommodations had lower passing rate on the United States Medical Licensing Exam (USMLE) [24]. Students who don't pass USMLE on the first try take longer to complete USMLE Step examinations, often resulting in delayed graduation [8, 24]. For students with cognitive/learning disabilities who are unable to receive accommodations on the USMLE Step 1 exam, their scores are 12 points lower than the average population of test takers..

In contrast, those who receive accommodations are 6 points lower than the average population of test takers [9]. This information further proves that barriers remain for competent students when not given their proper accommodations [8, 9, 24]. Therefore, there is a need to investigate the medical education learning environment to ensure robust support systems for these students [24].

In Searcy et al. [21], mean MCAT scores and acceptance rates were not significantly, 43.9% of students who received extra time vs. 44.5% of those who had standard time and were accepted into medical school, different among those who received extra time compared to those who did not [24]. Yet, students who tested with extra time performed less well on the USMLE Step examinations or repeated the exam and had delays in graduation. A recent study looked at MCAT vs. USMLE performance within cognitive (psychological, learning disorders, and ADHD) and noncognitive groups of disabilities (physical disabilities, deaf and hard of hearing (DHOH), and others) [8]. Students with noncognitive disabilities scored lower on Step 1 than their non-disabled peers, yet their Step 2CK scores are within the same range as the nondisabled group [8]. Students with cognitive disabilities score lower on both Step 1 and Step 2CK compared to students with noncognitive disabilities and students without disabilities [8]. The reason for this discrepancy is unclear and encourages more research in this area [8]. Medical school educators and administrators need to better understand potential barriers to medical education for students with disabilities to develop evidence-based supportive practices, supportive policies, procedures, and resources [8, 24]. There is consistency in studies that indicate common academic measures, which count for numerical scores on in-house and standardized exams, for students with disabilities were lower and less likely to graduate. Yet, these students' clinical performances were comparable to those without disabilities [8, 24]. Current research also found that the magnitude of differences in clinical performance varied by type of disability [8, 24]. For example, students presenting with psychological disabilities tended to perform lower clinically than others [23]. To have a better understanding of how to support student performances with varying disabilities, more research is needed to understand the interplay between disability and performance differences to improve the medical education process for students with disabilities and information about the accommodations provided on the USMLE Step examinations and compare them with MCAT accommodations [8, 24]. In Purkiss' et al.'s [10] study, USMLE scores were compared to MCAT scores, yet whether those students receive accommodations on the USMLE exam is unknown [8]. What was found was that student from the noncognitive disabled group (which encompass mobility, physical, chronic health, deaf and hard of hearing, and low vision) did score lower on USMLE Step 1 compared to the global population but performed the same on USMLE Step 2CK [8, 16]. The cognitively disabled group (psychological, learning, and ADHD disabilities) scores were lower on USMLE Step 1 and Step 2CK than the global population [8, 16]. There is a positive correlation between MCAT scores vs. USMLE scores, yet the study did not indicate whether the students studied did receive accommodations on that standardized exam [8, 16]. Knowing this limitation could be helpful in narratively explaining why students with disabilities struggle on these exams.

In a study from 2013, clinical clerkship performance of students with protected disabilities from a mental impairment, but not physical impairment, was below that of students without protected disabilities [23]. However, the magnitude of the differences was small, and whether these present differences difficulties in practice is unknown [23]. It is also important to note that early research from the 2000s focused on academic performances from a numeral standpoint (letter grades, step 1 scores) rather than clinical abilities. Studies indicate that care by physicians with disabilities allows for greater empathy of patients [4]. There continues to be a difference in graduation rates between students with and without protected disabilities shows to be more noticeable in students with disabilities, yet due to the limitation of the study being within a single institution is yet again another indication why there needs to be more research [23, 25]. Reasons for differences during medical school and subsequent performance during and beyond residency training should be further assessed. As a starting point, as suggested by the Purkiss et al. [10] article, to continue to look at the connection between MCAT and USMLE scores may better advise stakeholder regarding the academic performance of applicants with disabilities so they can be further supported [8, 25]. Since the model conducted had a significant disability by MCAT collaboration, showing that MCAT scores were related with similar changes in USMLE scores regardless of disability status [8, 25].

5 The need for more research

It is critical to further research barriers facing people with disabilities in medical school and postgraduate training curriculums to understand better ways of mitigating those barriers [3]. More research is also needed to determine the number of people with disabilities applying to medical school and their admission rates, graduation rates, and career experiences [3]. Because of the absence of scholarly literature in this field, physicians and medical students with disabilities should be encouraged to document their own experiences and practice strategies to develop successful models [3]. The stigma around disclosing disabilities is still prominent yet providing anonymous spaces more self-disclosure if shown to occur [13]. Such documentation would help medical educators construct plans and modifications to address barriers facing medical students with disabilities [3]. Transparent policies around disability disclosure can be produced to allow students to safely request accommodations without fear of stigma [13].

One study examined the prevalence of sensory impairments in medical students and whether medical schools used best practices to set admissions criteria [14]. Students with Physical and Sensory Disabilities (PSDs) were reported to be accepted into and graduating medical school at low rates compared to the general medical student population [14]. Additional studies are necessary to understand why lower graduation rates occur for those with PSD [14].

A longitudinal study is needed and a detailed review describing successful physicians who have navigated the work-life balance of utilizing accommodations. Such publications would provide much-needed insight into modifying accommodations to best support this group of students [8, 14]. In addition, further research is needed to examine the impact of academic accommodations for medical students with ADHD and other high-profile disabilities, investigating a possible relation between academic performance, symptom severity, and the granting of extended time on exams or providing a limited distraction testing environment [8]. A recent study from Purkiss et al. [10] also indicated that there needs to be a better understanding of MCAT performance in association with USMLE scores in students with disabilities that can aid in making informed decisions about these students [8].

6 Discussion

Physician diversity improved care for underserved populations, yet relatively few physicians have disclosed [13, 27]. However, self-disclosure increases when there is an ability to report anonymously, roughly a 5% difference in disclosure rates when reported anonymously [13]. By creating a safe place within medical schools to disclose disabilities without being anonymous, this practice could feed forward into professional practice for better representation [13, 27]. The underrepresentation of medical students and physicians with disabilities is challenging because having inclusive representation of diversity professionals improve patient outcomes [27]. However, as can be indicated from the Searcy [21] article, there are additional barriers once students are accepted [8, 27]. Most U.S. medical schools' technical standards do not adequately support accommodating students with disabilities to represent new creative accommodation for a variety of disabilities including physical disabilities without risking anyone's health or safety [8, 27]. Findings of a review of institutions technical standards do suggest systemic exclusion by U.S. medical schools of individuals with disabilities [8, 27]. Second, the integration of students with disabilities in their medical school classes better understand the emotional reality of disabilities and become better able to care for patients with disabilities [8, 27]. Disability can be incorporated and be beneficial at the highest professional work levels [8, 27]. There is a belief that the disability topic's investment will show that justice and fairness provide social benefits worth the cost [8, 27]. While still few, many physicians with disabilities serve in clinical, educational, and research roles [8, 27]. No studies detail the barriers for physicians with physical disabilities [8, 27]. Possible internal and external factors may contribute to these students' underrepresentation in medical education [5, 6]. These factors could include a lack of access to appropriate accommodation at any point in the educational pipeline [5, 6]. There is a lack of knowledge about accommodation strategies, such as concerns about the institution's concessions cost which contribute to the stigma and barriers to disclosure [5, 6]. There is a possibility that a combination of the above factors contributes to underrepresentation [5, 6]. The rise of competency-based medical education has helped drive these changes. Broadening medical education aims to integrate teaching in professionalism, learning, and improvement as part of one's practice and finally shifting focus from assessment to measuring performance rather than only knowledge [5, 6]. With this approach, schools can assess students with disabilities' understanding and implement reasonable accommodations to allow students to utilize alternative assessments to demonstrate their mastery of skills [5, 6].

Technical standards are criteria and abilities required for students upon being admitted into medical school [13]. These standards are also expectations throughout and when students graduate from medical school.. Many focus on technical standards when discussing students with disabilities, which suggests a strong emphasis on technical skills [6]. Several essential questions regarding the role of technical skills and their relative importance should be addressed in the context of graduation competencies, such as knowledge and intelligence, professional attitude, and the ability to communicate and interact effectively [4]. Yet, these technical standards can remain a primary barrier for students entering, during, and completing medical school [13]. In addition, some schools' technical standards do not comply with the ADA laws, and therefore frequent review should be conducted of these standards as disability accommodations continue to evolve [13].

Providing better support and understanding of resources can aid the student and the faculty working with these students. These supports can give evaluative assessments to find students with disabilities sooner, which is costly but can be worth the financial gain in providing quicker resources for students and educating faculty in these evaluations and disability types. Suppose schools offer these resources instead of requiring a student's ability to pay for or increase their financial burden, which is why most students do not know or have worked on their disability due to cost. In that case, these resources can become part of the support of financial infrastructure [26]. Continued support solutions need to include creating professional teams that collaborate closely with disability professionals to ensure proper treatment of students with disabilities such as providing reasonable accommodations while continuing developing a pool of resources. Ongoing and continuous monitoring of requirements and functions is essential (technical standards) for each medical school program's stage, as Kezar suggested [12]. Finally, continue to educate administrators, staff, and faculty about learning disabilities so that all stakeholders can holistically support these students [26].

References

McKee M, Case B, Fausone M, Zazove P, Ouellette A, Fetters M. Medical schools’ willingness to accommodate medical students with sensory and physical disabilities: ethical foundations of a functional challenge to “Organic” technical standards. AMA J Ethics. 2016;18(10):993–1002.

Kessler R, Adler L, Barkley R, Bierderman J, Conners KC, Demler O, Faraone S, Greenhill L, Howes M, Secnik K, Spencer T, Ustum BT, Walters E, Zaslavsky AM. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the Unites States results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. AM J Psychiatry. 2006;183(4):716–23.

Antshel K, Barkley R. Developmental and behvioral disorders grown up: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2009;30(1):81–90.

Curry RH, Meeks LM, Iezzoni LI. Beyond technical standards: a competency based framework for access and inclusion in medical education. Acad Med. 2020;95(128):S109–12.

Javaeed, A. (2018). Learning Disabilities and Medical Students. MedEdPublish.

Haque O, Stein M, Marvit A. Physician, heal thy double stigma- doctors with mental illness and structural barriers to disclosure. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(10):888–91.

Donlan, M. (2016). Voiceless in medical school students with physical disabilities. dissertations, thesis, and master projects. Paper 1499449833.

Meeks LM, Case B, Stergiopoulos E, Evans BK, Petersen KH. Structural barriers to student disability disclosure in US-allopathic medical schools. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/23821205211018696.

Meeks L, Herzer K. Prevalence of self-disclosed disability among medical students in U.S. allopathic medical schools. JAMA. 2016;316(21):2271–2.

Purkiss J, Plegue M, Grabowski CJ, Kim MH, Jain S, Henderson MC, Meeks LM. Examination of medical college admission test scores and U.S. medical licensing examination step 1 and step 2 clinical knowledge scores among students with disabilities. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(5):e2110914. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10914.

Roseraugh C. Learning disabilities and medical school. Med Educ. 2000;34:994–1000.

Kezar L, Kirschner K, Clinchot D, Laird-Metke E, Zazove P, Curry R. Leading practices and future directions for technical standards in medical education. Acad Med. 2019;94(4):520–7.

Meeks L, Herzer K, Jain N. Removing barriers and facilitating access: increasing the number of physicians with disabilities. Acad Med. 2018;8(93):540–3.

DeLisa J, Thomas P. Physicians with disabilities and the physician workforce: a need to reassess our policies. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;84(1):5–11.

DeLisa J, Lindenthal JJ. Learning from physicians with disabilities and their patients. AMA J Ethics. 2016;18(10):1003–9.

Meeks L, Case B, Herzer K, Plegue M, Swenor B. Change in prevalence of disabilities and accommodation practices among U.S. Medical schools, 2016 vs. 2019. JAMA. 2019;322(20):2022–4.

Miller T, Nigg JT, Faraone S. Axis I and II comorbidity in adults with ADHD. J Abnorm Psychol. 2007;116(3):519–28.

Tuttle J, Scheurich N, Ranseen J. Prevalance of ADHD diagnosis and nonmedical prescription stimulant use in medical students. Acad Psychiatry. 2010;34(3):220–3.

Romberg F, Shaywitz B, Shaywitz S. How should medical schools respond to students with dyslexia? AMA J Ethics. 2016;18(10):975–85.

Eickmeyer S, Do K, Kirschner K, Curry R. North american medical schools experience with and approaches to the needs of students with physical and sensory disabilities. Acad Med. 2012;87:5670573.

Searcy C, Dowad K, Hughes M, Bladwin S, Pigg T. Association of MCAT scores obtained with standard vs. extra administration time with medical school admission, medical student performance, and time to graduation. JAMA. 2015;313(22):2253–62.

Sharp K, Earle S (2000) Assessment, Disability and the Problem of Compensation. Assess Eval High Educ 25(2):191–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/713611423.

O’Callaghan P, Sharma D. The severity of symptoms and quality of life in medical students with ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2014;18(8):654–8.

Meeks L, Engelman A, Booth A, Argenyi M. Deaf and hard of hearing learners in emergency medicine. Educ Adv. 2018;19(6):1014–8.

Meeks L, Plegue M, Swenor B, Moreland C, Jain S, Grabowski C, Eidtson W, Patwari R, Angoff N, LeConche J, Temple B, Poullos P, Guzman-Sanchez M, Coates C, Low C, Henderson M, Purkiss J, Kim M. Trajectory of medical students with disabilities: results from the pathways project. Acad Med. 2021;96(11S):S209–21.

Meeks L, Stergiopoulos E, Petersen K. Institutional accountability for students with disabilities: a call for liaison committee on medical education action. Acad Med. 2021;97(3):341–5.

Petersen, K.H. (2020). Increasing Accessibility Through Inclusive Instruction and Design. Disability as diversity. Chapter 7(pp 143–162)

Ricketts C, Brice J, Coombes L. Are multiple-choice tests fair to medical students with specific learning disabilities? Adv Health Sci Educ. 2010;15:265–75.

Schwarz C, Zetkulic M. You belong in the room: addressing the underrepresentation of physicians with physician disabilities. Acad Med. 2019;94:17–9.

Swenor B, Meeks L. Disability Inclusion- Moving Beyond Missions Statements. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(22):2089–91.

VanMatre R, Nampiaparampil D, Curry R, Kirschner K. Technical standards for the education of physicians with physical disabilities, perspectives of medical students, residents, and attending physicians. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;83:54–60.

Teherani A, Papadakis M. Clinical Performance of medical students with protected disabilities. JAMA. 2013;310(21):2309.

Lin J, Oransky I. The Americans with disabilities act and afterwards: disabilities in medical education and practice. Pulse, The Medical Student Section of JAMA. 1998;279 (1).

Zazove P, Case B, Moreland C, Plegue M, Hoekstra A, Quellette A, Sen A, Fetters M. U.S. medical schools’ compliance with the Americans with disabilities act: findings from a national study. Acad Med. 2016;91:979–86.

Blacklock B (2015) Enhancing Access in Medical and Health Science Programs: The college Model. Disability Compliance for Higher Education.

Jain M (2018) Association of American Medical Colleges, Accessibility, Inclusion, and Action in Medical Education: Lived Experiences of Learners and Physicians with Disabilities.

Lisa M, Neera J (2016) The Guide to Assisting Student with Disabilities. Springer Publishing Company

Meeks LM, Jain NR. Accommodating chronic health conditions in medical education. Disabil Compl Higher Educ. 2018;23:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/dhe.30432.

Funding

NA

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This manuscript was written collaboratively by medical students and faculty. The passion of the topic of student support was expressed within each word, by each author. RN wrote the main manuscript, Brandon C, Brooke C, KF and RG took split the manuscript into 4 ways and edited pieces and contributed their views to their assigned sections. SG provided editing time to make sure that the manuscript was sound. Each author contributed equally to the writing and editing of this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

NA.

Informed consent

NA.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nash, R., Conner, B., Fellows, K. et al. Barriers in medical education: a scoping review of common themes for medical students with disabilities. Discov Educ 1, 4 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-022-00003-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-022-00003-0