Abstract

This article argues that the Bank of Japan is caught in a bind owing to both its quantitative easing policies of the last two decades and chronic inflation. In response to quantitative tightening abroad, the Bank of Japan is under pressure to raise interest rates and/or allow yields on ten-year government bonds to rise. This is because the response to inflation among G7 nations has undermined the yen, which have made clear the flaws of the Bank of Japan’s approach to restoring economic growth, namely quantitative easing as any attempt to adapt to international efforts to address inflation, using monetary methods, runs the risk of triggering a cascade of loan defaults due to illiquidity issues both at home and in foreign markets. To demonstrate this, the article evaluates Japanese quantitative easing measures, including the Bank of Japan’s yield curve control policy, and assesses the problems it faces due to inflation and the responses to it, including monetary tightening abroad.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent years, the global economy, particularly those economies of the so-called developed world, have begun to recognize that inflation is chronic and thus governments and their monetary authorities have embarked on quantitative tightening (QT) and monetary tapering measures in response. History shows us that addressing inflation at home can have significant ramifications abroad, which, owing to the increasingly interconnected nature of the world’s economies, certainly remains the case today. Furthermore, how each state responds to inflation will be inflected by a variety of factors including the policy apparatus at their disposal. Thus, understanding inflation in the context of multiple decades of quantitative easing measures enacted by central banks across the developed world is an important matter. Moreover, owing to various economic factors at home as well as general uncertainty, the response to chronic inflation is likely to be disorganized and hence cause unforeseen issues to arise in global financial markets due to the entrenched nature of risk. Understanding each state’s capacity to respond to this is hence a critical issue and requires an in-depth analysis of the economic conditions of each state and how it impacts on their ability to respond to the risks that global inflation poses.This article argues that long-term quantitative easing has limited Japan’s ability to effectively respond to inflation. Japan is a particularly pertinent case study in this respect a) because it was the first country to implement it and thus has the longest track record for QE; b) the lessons learned from an analysis of Japan may be applicable to other countries that have depended on long-term QE to attain economic growth; and c) it has been used as a case study to explain why QE is, in fact, misunderstood inasmuch as it provides necessary stimulus to the economy which does not cause hyperinflation (Bernanke and Reinhart 2004; Morgan 2012; Kelton 2020; Shirakawa 2021). In spite of this, this article argues that both inflation in Japan and in key international markets have exposed a frailty in the economy at large caused by the Bank of Japan’s (BOJ) QE measures, which may be applicable to other countries whose economies have been reliant on QE also.

The ostensible idea behind QE policy in Japan has been to make conditions for lending favorable to the banks so that they carry out investment in the real economy. This was the traditional basis of Japanese industrialization both prewar and postwar but it came with rigorous mechanisms that guided the flow of credit in the economy. The traditional model centered on a government-bureaucratic guidance of credit which was funded to a large extent by Japanese savings accumulated in public/state banks and channeled off to government-affiliated companies and lending bodies as well as local governments (Johnson 1982; Werner 2003; Brown 2013). Although Japan has attempted to retain aspects of its state-guided model of economic growth (Robinson 2017), the fact is that today, Japan is a much different economy owing to the reforms carried out after the Japanese bubble economy crashed in 1991 (Gibney 1998; Sasaki, 2010; Yamamoto and Toritani 2023). Thus, the QE implemented in recent decades and its impact on the economy must be understood in order to assess the risks inflation poses to the Japanese economy as it is today.

As this article demonstrates, while the BOJ did attempt to bring about inflation in Japan, this was on the pretense that it would be a marker for the extension of credit into the real economy by Japan’s banks. Inflation not caused by this is a very different phenomenon and poses a huge risk to the Japanese economy. To explain why this is the case, the analysis is divided into four sections. The first section explains and details the BOJ’s experiments in QE, the second section then evaluates its efficacy and success using empirical economic data. The aim here is to suitably contextualize the Japanese economy and the BOJ’s agency therein before assessing the impacts inflation has had on the BOJ itself and its capacity to maintain QE and manage the economy. The third section qualifies what kind of inflation Japan is undergoing in order to explain why it is not directly related to Japan’s QE policies and certainly should not be considered proof of success. The fourth section then uses empirical economic data to show how inflation both in key international markets and in Japan has impacted on the Japanese economy and in what ways both the BOJ and Japanese financial institutions have sought to respond, while a summary of the main arguments is presented in the conclusion.

QE in Japan: a brief overview

The goal of QE is to induce rises in the rate of credit creation by bailing out the banks so that they step up lending in the economy. For Japan, it entailed the BOJ greatly expanding the “monetary base,” or central bank reserves, and depositing them into the accounts of certain financial institutions held at the BOJ itself. Of course, the BOJ generally buys up the Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs) it issued or other financial assets such as mortgage-backed securities from commercial banks, life insurance companies and other financial institutions in open market operations and then deposits the funds in the general account that these institutions hold at the BOJ (Yamamoto and Toritani 2023). By issuing more bonds, the national debt increases.

Nonetheless, these deposits are fictitious assets created by the central bank that it uses to flush out toxic assets from financial institutions so that they can stay solvent (Brown 2013, 2019; Huber 2017). Central banks can take on toxic assets provided that demand for its bonds is sufficient enough to guarantee the credibility of the currency. Central bank reserves are then traded between commercial banks as a check-clearing mechanism and are not injected into the “real economy,” that is, into the bank accounts of regular customers and businesses. For this reason, the huge increments in bank reserves themselves have not directly caused inflation by increasing the money supply in Japan. Rather, the logic goes, that financial institutions would offload toxic assets for neutral ones—central bank reserves backed by the credibility of the bank—and, on that basis, would increase lending in the real economy by creating deposits through loan issuance.

The BOJ implemented QE for five years under the Koizumi government (2001–2006) given that interest rates could not be lowered any further (Bank of Japan, May 1, 2001). After an eight-year hiatus, QE returned under the second Abe administration (2012–2020; first: 2006–2007) in 2013 (Prime Minister's Office of Japan 2014) and has been in effect until very recently. The goal of lowering rates on uncollateralized lending has traditionally been to simulate conditions favorable to credit creation by lowering perceived risk among investors. The first hand of QE is central banks trading newly created assets for toxic ones from commercial banks. The second hand is central bank policy of lowering rates for lending and other such measures which are designed to encourage the banks to lend more. Crucially, unlike economic models of the past, there is no significant credit guidance mechanism provided by the state.

However, even before QE proper, the BOJ had lowered rates as low as they could feasibly go, and so the shift to focusing on central bank reserves held by financial institutions at the BOJ was meant to lower expectations of rates increasing in the future among investors (Tanaka 2009). This is what is meant by “simulating market conditions;” the apparent idea is to carry out operations to alter the indices associated with assessing market conditions in an attempt to lower the perception of risk among the banks so that they issue new loans necessary for credit-based growth (Tanaka 2009). In both Koizumi's and Abe's economic strategies, the goal was to overcome deflation. In Koizumi's case, the primary cause was debt overhang as a result of Japan’s post-bubble deflationary spiral, while in Abe's case, it was the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007 and the Tohoku Earthquake and Fukushima Nuclear Disaster of 2011, which had exacerbated Japan’s economic problems.

Both Koizumi’s and Abe’s economic programs were based on targeting a given inflation rate as per Japan’s Consumer Price Index (CPI) and buying up long-term JGBs to increase the balance of current accounts at the BOJ up to a given overall target (Bank of Japan, May 1, 2001). Both came with promises of economic reform and a consistent monetary policy to keep interest rates low. One drawback was that Japanese financial institutions traditionally viewed reserves as an indicator of risk as it pertains to a given institution. Essentially, excess reserves meant bad finance, and so the enormous increase in reserves held in accounts at the BOJ had the effect of obfuscating perceived risk on the call market (Miwa 2011). It also undermined the incentive to make investments in the call market in the first place because the BOJ became the main supplier of short-term funds. Furthermore, with the economy undergoing deflation, there was little need to use these reserves for anything else other than balancing accounts once the bulk of toxic assets was offloaded.

Thus, Koizumi and Abe made lavish promises of economic reform in order to stoke up demand for credit in the economy. Indeed, many perceived structural changes to the Japanese economy to be necessary, particularly during the Koizumi administration, which had to deal with the issues of excess debt, excess personnel and excess capacity due to deflation after the collapse of the bubble economy and adapt to a burgeoning globalized capitalism which required adherence to various new standards and expectations (Sekioka 2004). In essence, Japanese banks had suffered enormous losses due to the Plaza Accords of 1985 and the subsequent the enactment of the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) capital adequacy ratio in 1988 (fully implemented in 1993) by European and American countries (Yamamoto and Toritani 2023), and thus throughout the lost decade that followed the collapse of its bubble economy, Japan underwent a series of reforms aimed at internationalizing the economy.

Most crucial to this was to become reliant on corporate profitability and international investment at the expense of the government’s traditional reliance on Japanese savings at public banks for public investment with the central bank as the so-called “lender of last resort” (Yamamoto and Toritani 2023, 297–8). The liberalization of Japan’s economy was carried out by installing market mechanisms to government and public functions through the use of semi-autonomous bodies known as Independent Administrative Institutions; privatizing key public services; disaggregating bureaucratic organizations, deregulating its financial sector; implementing austerity; and promoting and participating in the establishment of international free-trade zones and partnerships (Pope 2021).

While debate remains over exactly how necessary these changes were, many economists were sanguine about economic prospects after the Koizumi administration owing to the fact that commercial banks were able to dispose of “bad loans” and improve profitability, both attracting capital to Japan and allowing Japanese corporations to utilize their position in global markets by investing in growth centers of the time such as China (Sakai 2006). This is also one reason why QE was brought back during the second Abe administration which, commencing at the very end of 2012, was similar to the Koizumi administration inasmuch as it followed an economic crisis and a response by previous administrations considered to be unsatisfactory by much of the electorate. QE, then, was seen as a means to directly influence financial conditions in an economy which over the years, owing to structural changes, lost its capacity to indirectly finance investments through preferential credit administered through a nexus of bureaucratic bodies, local government and banking networks.

Koizumi's and Abe’s administrations were successful in reducing the unemployment rate, even if it came at the cost of increasingly irregular, low-paid and insecure work, and increasing profitability among Japanese corporations by, for one, inducing booms in the stock market. It is likely that this was considered to improve Japan’s position in the international arena to negotiate conditions favorable for its national interests with regards to the establishment of multilateral free-trade agreements such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership. The logic, then, was that QE would allow the government to have its cake and eat it too. That is, amidst liberalization measures, by injecting liquidity into financial markets, the central bank could still intervene to protect its own credibility by overcoming deflation. Thus, it sought to replace interest-bearing sovereign debt instruments held by Japanese financial institutions with central bank reserves that could be traded among relevant parties to clear out blockages in the financial plumbing as the stock market soars in an attempt to increase productive investments in the real economy so as to induce inclusive, credit-based growth that increases incomes as well as profits, and hence “reflates” the economy (Nagai, February 6, 2013).

Unlike the Koizumi administration, the Abe administration added to its economic arsenal by vastly expanding Japan’s fiscal spending, unconcerned about its potential to crowd out private investment. Again, the logic was that government spending would excite private entrepreneurship by creating opportunities for spending and hence consumption, which over time would give corporations leeway enough to increase wages. Abe’s interest in Japan hosting the 2020 Olympics may be seen in this context (Yamamoto and Toritani 2023). Moreover, this spending was meant to put additional cash in the hands of Japanese citizens and businesses to spend and hence elevate effective demand.

However, investors exploited the low interest rates by taking yen and converting it to foreign currency in order to buy up foreign financial equities and securities that had higher yields. This was by no means an unforeseen consequence of QE, while the low yen was also the result of the BOJ and private financial institutions buying up US treasuries (USTs) with the gains made from the country’s trade surplus and primary income (Yamamoto and Toritani 2023). Nonetheless, while the BIS advocated stricter capital requirements in the form of Basel III, Japanese banks generally struggled to adhere to it (Financial Services Agency, March 25, 2022). Rather, larger banks were able to circumvent some of these regulations by shadow banking practices and hence were able to profit from arbitrage by investing in securities, derivatives and equities, and thus bid up their prices. Shorting the yen was one means to do it and it caused Japanese corporations to become highly leveraged on foreign assets and debt instruments.

In addition, the BOJ began to scale-up its repurchasing of long-term JGBs in order to reduce expectations of hikes of short-term rates. This indeed rebalanced the portfolios of financial institutions but, as stated, also encouraged them to increase lending so as to profit from arbitrage on interest rates (Tanaka 2009). Without a rigorous credit guidance mechanism or framework, the BOJ attempted to steer it towards the formation of tangible capital, by establishing inflation targets essentially as promises to the financial sector whilst convincing investors that even with inflation, the BOJ would not raise interest rates. This induced booms in the stock market as the BOJ bought in bulk equities such as Japanese Real Estate Investment Trusts (J-REITS) and Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) to compel financial institutions to do the same by bidding up prices (Tanaka 2009, 92–3).

The result is that by the end of March 2021, the BOJ had become a major shareholder (10% or above) of 71 companies listed on the Japan Exchange and the majority shareholder of 5 companies, as well as a major holder (more than 5%) of approximately 30% of the 62 J-REITS listed on the exchange (Yamamoto and Toritani 2023, 303; Tomita, June 27, 2018). This is often heralded as another reason why the BOJ would not raise rates given that it would lead to unrealized losses on equities. The consequence of this was that large Japanese businesses were encouraged either to finance capital investment with their own retained earnings or by simply raising capital, without taking out loans at the bank (Yamamoto and Toritani 2023, 304). Thus the goal appeared to be to kick-start productive activity by triggering a bubble in the equity markets which would increase demand for credit from small to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and regional businesses also as large corporations raise capital for certain ventures.

Nonetheless, it is unlikely that this act had any significant impact on market sentiment due to the fact that losses held on the BOJ’s books in themselves represent little-to-no risk to the BOJ. Rather, the impact of unrealized losses on equities in general—say, by raising rates—on the BOJ would depend on the extent to which it undermines the yen as insolvency for a central bank pertains to the size of GDP committed to making interest payments on debt and the credibility of and demand for the currency. The BOJ becomes insolvent when the yen collapses and not enough people want to buy Japanese sovereign debt. Thus, financial institutions and large businesses were likely encouraged to profit from investment in securities instead of making long-term investments in the real economy per se.

During the Abe administration in particular, the BOJ ramped up efforts to encourage banks towards making tangible investments in the real economy. While the Koizumi administration had generally relied on economic liberalization measures to encourage private entrepreneurship, QE policy under Abe was dovetailed at times with helicopter money which aimed to stoke demand for credit. Both the Koizumi and Abe governments implemented tax cuts to the private sector, putting cash in the hands of Japanese corporations (Tax Commission Japan, 2002; Woodman, December 14, 2017), but the Abe government took this a step further when it provided a one-time universal basic income to each household based on family size during the state of emergency issued in 2020 due to COVID-19. During troughs in reported infection rates, the government also launched a targeted campaign to get citizens to travel to Japan's economically fading regions to support the economy while international travel was restricted by significantly subsidizing expenses both for the holidaymakers and businesses, whilst also providing loans to businesses struggling to make ends meet (Ministry of Internal Communications, October 1, 2020; TravelVoice, April 7th,2020).

Thus, we see that Japan experimented with two quite divergent forms of QE. Not all differences were necessarily planned pre-hoc but appear to have came as responses to an economic revitalization strategy that was not working as planned. On the whole, the first experiment with QE under the Koizumi administration maintained a compliance with the established monetarist orthodoxy through its commitment to neoliberal reform—privatization, deregulation and austerity. On the other hand, the Abe administration provided a more heterodox approach with more moderate reforms overall and, similar to the U.S. response to the GFC, expanding fiscal spending in an attempt to generate investment opportunities and increase the spending power of businesses and Japanese citizens, if only temporarily.

Nonetheless, both attempts at QE ended in failure overall as with no substantial mechanism for guiding banking credit to productive sectors, Japanese banks focused instead on gains made in speculative markets. This is outlined in the following sections, below.

Evaluating Japan’s QE experiments

The goal of this article is to analyze and assess the problems that inflation poses to the BOJ given its long-term reliance on QE to avoid an illiquidity crisis. To do so, it is necessary to first empirically evaluate Japan’s experiments with QE overall so as to provide a suitable context in which to situate the Japanese economy for further inquiry. This is carried out in this section.

As stated, the ostensible goal of QE is to achieve credit-based growth. Therefore, in evaluating the success of QE, we must first examine the extent to which credit creation in Japan increased. This is provided in Fig. 1 below.

Created by author using data from BOJ database. *M2 from 1980 until March, 2003 was calculated based on the year-on-year rate of change per month. Rates of change are given to 1 decimal point by the BOJ so it is reasonable to assume a moderate degree of error in nominal values of M2 predating April, 2003. However, the degree of error is not large enough to misrepresent the broader picture of credit creation in Japan as explained below

The graph above shows the monetary base (reserves held by financial institutions at the BOJ), the money stock (money created by financial institutions themselves) and the rate of credit creation since 1980. Credit creation actually expanded in 2006 when the BOJ ended its QE program and increased the interest rate on short-term lending from 0% to 0.25% in Koizumi’s final months as prime minister (Bank of Japan, May 31, 2007). This caused the monetary base to contract. It, however, did not translate into a significant increase of the Japanese money supply, as Fig. 2 below clearly shows. In both attempts at QE, large increases in the outstanding balance on accounts held at the BOJ did not lead to a significant increase in the Japanese money supply because banks did not increase the rate of extension of credit to the real economy in the form of loan issuance.

Abenomics promised to maintain a price stability of 2 per cent inflation every year as per the CPI as its “inflation overshoot commitment,” whilst the Koizumi administration sought to keep it at 0%, targeting an end to deflation rather than inflation per se (BOJ, April 4, 2013). The BOJ repurchased JGBs to increase their value so that JGB expenses for a given fiscal year would be covered by newly issued government bonds with the leftover included in the government’s general account. In this way demand for JGBs is crucial to the BOJ. Financial institutions themselves decide what kinds of investments to make from the gains made by selling JGBs back to the BOJ. That they do resell these bonds and purchase new ones, however, is essential to the BOJ for it to be able to meet the state’s budgetary needs (Yamamoto and Toritani 2023).

To elaborate further on this point, Fig. 3 below shows how successful each administration was in maintaining these inflation commitments and the cost this had overall in terms of national debt.

Created by author using data from Ministry of Finance (December, 2022) and the Cabinet Office’s National Accounts of Japan. * Inflation = All products excluding fresh foods. Inflation rate based on monthly CPI, year-on-year. ** GDP Deflator = Quarterly data, year-on-year. *** Outstanding balance from Graph 4 in Ministry of Finance (December 2022: 5). Fiscal year 2022 based on the Japanese government’s second provisional budget. Outstanding balance does not include investment-and-loan bonds from Japan’s Fiscal Investment and Loan Program because they are issued by independent administrative institutions or special corporations without government guarantee

Figure 3 shows that the outstanding balance on JGBs did increase markedly, while both Japan’s CPI and the more encompassing GDP Deflator did not record any consistent inflation throughout both periods. As stated above, a large part of both administration's QE strategies involved managing perceptions of risk and expectations thereof. It stands to reason that financial institutions are unlikely to assess risk any differently if the BOJ does not deliver on its commitments in economic management. The problem is which comes first, the inflation and elevated lending, or elevated lending and then inflation? Without the extension of credit to the real economy, government promises of a given inflation target ring hollow.

In 2016, the BOJ attempted to tackle the issue of the lack of demand full-on by implementing a negative interest rate of -0.1% on short-term lending, effectively taxing reserves held at the BOJ, as well as a YCC on 10-year JGBs to keep yields at approximately 0% by introducing a “fixed-rate bond-buying operation” (BOJ January 29, 2016; September 21, 2016). 10-year JGBs are used as indicators of long-term interest rates in Japan, while interest rates are conventionally decided by market forces. Thus, the government buying up these bonds was another act of ‘simulating reality’ to manage market expectations; that is, both short-term and long-term rates were effectively decided by the BOJ. The goal was to convince financial institutions to increase lending, and the method was both carrot and stick: The carrot, or, rather, the promise thereof, was the YCC which was implemented to show these institutions that the BOJ was committed to low interest rates and inflation long-term. The stick was the tax on reserves held at the BOJ which simply was meant to prod financial institutions into action—that is, to carry out productive investment.

There are, however, a number of problems with the BOJ’s line of reasoning. First, a major issue is that commercial banks rely on market indicators to assess risk because they understand that government policy can change within investment cycles. Also, they are likely to be more convinced of this when the government fails to meet its own targets using these indices. Thus, using these indicators as instruments of government policy likely undermines the indicator itself rather than changes perceptions of the economy, causing some institutions to become less prepared to make long-term investments in the real economy. More importantly, the government buying up equities to assure these institutions it would have no reason to increase rates does not change market dynamics that would force the BOJ’s hand, such as the effects of economic conditions abroad on its currency, its trade balance and the Japanese bond market, all of which are discussed in the “BOJ and global inflation” section, below. Furthermore, it does not change the fact of Japan’s declining population due to low fertility rates which spells the bottoming-out of domestic demand for credit long-term.

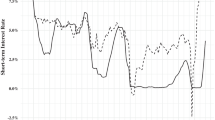

To assess the success of the BOJ’s YCC policy, Fig. 4 shows the yield curve for JGBs since the start of the Abenomics, the initiation of the YCC, and the recent decision by the BOJ to loosen the YCC from 25 basis points to 50.

The yield curve returned to approximately the same level as at the start of Abenomics, by the end of fiscal year 2022 and shortly after the BOJ decided to loosen its YCC on 10-year JGBs (BOJ December 20, 2022). However, the consequence of the YCC policy is that while the BOJ owned approximately 12.5% of JGBs before Abenomics began (BOJ, March 29, 2013), that increased to approximately 50% by the end of fiscal year 2022 (BOJ, March 14, 2023). The BOJ is the only central bank in the world that maintains negative rates on short-term lending but now the central bank owns large portions of the Japanese equity market and most of the bond market.

Both reason and evidence suggests that this causes illiquidity issues. For example, at the end of 2022, the BOJ was reported to possess over 100% of newly-issued 10-year JGBs (Wada et al. November 2, 2022). Due to the BOJ’s aggressive purchasing of JGBs, there were 1247 failures to deliver on JGBs in January 2023 (BOJ, March 10, 2023), the highest monthly record since before the GFC (Nikkei, February 11, 2023). In recent years, Japan’s current account has gone into deficit which places more importance on the issuance of JGBs as a means to finance government spending and debt-service. Thus, bond market dysfunction represents a sizeable risk to the BOJ and the economy itself.

Put simply, there is a tripartite issue at play. That is, 1) the market depends on financial institutions buying BOJ assets in order to function; 2) the BOJ aggressively purchasing JGBs and even equities runs the risk of undermining market confidence in these assets; 3) the BOJ must continue to scale up its purchasing of assets nonetheless so long as it becomes increasingly dependent on bond issuance. In short, the BOJ is in desperate need of productive, credit-based growth for the economy to be able to climb out of this quandary but this is not what activities the banks are primarily engaged in, as shown below.

As stated, without guidance in how credit is used, the banks have simply profited from arbitrage by investing in high yield securities whilst the BOJ has been forced to buy back its own bonds to maintain rates. This is shown in Fig. 5, below.

The BOJ implemented the YCC policy in order to prevent the price of JGBs from declining. Banks capitalize on these low rates to carry out Over-The-Counter (OTC) transactions in the derivatives market, the overwhelming majority being interest-rate swaps. As a result, the BOJ must buy up the excess supply of government debt in the market in order to maintain prices and to ensure that Japanese financial institutions continue these transactions. Despite its promises and commitments, the BOJ’s role is at present reactive to the Japanese financial sector, not the other way round.

To buy this debt, the government issues new debt and hence continually increases the scale of debt financing so long as the Japanese economy does not recover, which it is unlikely to do if the banks invest in non-productive, speculative assets. However, the market dysfunction this causes risks reducing the private demand for JGBs even further which will increase the disparity between the market price for JGBs and the nominal price that is being manipulated by the BOJ and hence require even larger interventions in the bond market. The obvious and immediate outcome of this is an increase in Japan’s national debt, further illiquidity problems for the financial institutions the BOJ relies on, and potentially the depreciation of the yen which, if significant, would undermine its credibility. Furthermore, this is a vicious cycle because Japanese financial institutions are unlikely to extend credit for productive activities in Japan nor are they likely to find a consistent source of foreign demand for such purposes in such a scenario. This is one of the reasons why financial institutions have instead invested in OTC derivatives, as shown in Fig. 5, which have less regulatory oversight, and acquired foreign capital through international gateways like American Depository Receipts (Economist, March 16, 2023).

Created by author using data from BOJ’s database. *Includes 4-year and 6-year JGBs until end of fiscal year 2003 and 2006, respectively. These JGBs were merged to make a 5-year benchmark. Data also includes inflation-indexed bonds (10-year maturity) and floating-rate bonds (15-year maturity).** Data taken at end of fiscal year (March of the subsequent calendar year) for JGBs but at end of calendar year (December) for derivatives transactions. Thus, there is a three-month lag between derivative transactions in December and JGB data where data from the end of the fiscal year is provided. *** February 2023 data used for bond price at issue for FY2022 due to availability

Thus, the BOJ is caught in a bind as to how to attract or generate demand such that the economy may overcome the stagnation that has defined its post-Cold War era, with both allowing yields to rise and maintaining the YCC involving sizeable risk to Japan’s economy. The appropriate question one might ask is what changed? Japan has widely been used as an example as to why QE does not necessarily lead to hyperinflation in spite of all the prognostications to the contrary (Wray 2015; Wray & Nersisyan 2021). For this reason, the following sections provide the larger picture of this dilemma by, in Section 4, explaining the cause of inflation in Japan and outlining its overall impact on the economy, and, in Section 5, using empirical evidence to show how this further exacerbates the economic conditions the BOJ has attempted to manage.

Inflation, at last; only, not the good kind

One drawback to economic policy centered primarily on fixed targets such as, say, a 2% inflation rate, is clearly that sometimes context matters. The overarching goal for the Japanese economy is credit-based growth based on productive capital formation. Traditionally, the government of Japan generated credit for public works and welfare projects from the Japanese Postal Savings System through the Fiscal Investment and Loan Program and regulated banking, which permitted the Ministry of Finance to guide credit allocation for productive purposes (Johnson 1982; Werner 2003; Brown 2013; Yamamoto and Toritani 2023). In this sense, inflation may be seen to be an indicator of favorable economic conditions.

Nonetheless, the implication that inflation is necessarily a positive for Japan is simply not empirically supported. For example, Japan underwent inflation in the 1990s as a result of the financial crises in Asia (1997) and Russia (1998), which led to capital flight and the depreciation of the yen (Sasaki 2010, 269). This was not taken to be evidence that deflation had finally been vanquished as investors selling Japanese yen in bulk obviously does not constitute an empirical criterion among banks for them to further extend credit to domestic clients. Similarly, Japan Postal Savings exists today as Japan Post Holdings Co. Ltd., following the finalization of its privatization in 2015, in which the government of Japan (including local governments) now holds 34.33% of shares (JapanPost, March 31, 2023). While, the extent of effective control over credit guidance within Japan Post is still debated (e.g. Robinson 2017), the ‘wrong kind’ of inflation could reduce what influence remains if customers decide to withdraw their deposits en masse. For this reason, inflation in itself is not a deterministic criterion of good economic conditions.

What is necessary is determining the cause of inflation. As we shall see, the data suggests that inflation in Japan in 2022 was largely due to trade restrictions which caused price increases in energy and food, while Japan’s money supply did not significantly increase. This is a problem for Japan as it appears that domestic inflation is cost-push, meaning that raising rates would only increase the cost of borrowing and compound Japan’s illiquidity issues. For instance, while Japan's CPI placed the inflation rate at only 4.0% in December 2022 (Nikkei Shimbun, January 20, 2023), items that saw the highest price rises were mostly food and energy, signaling an issue in supply of goods and materials, not quantity of money (Table 1).

Elevated prices in essential goods places an immediate burden on households and businesses. Energy costs have increased owing to Japan’s sanctions on the Russian Federation which has limited the supply of energy to the nation. With no scalable energy resources of its own, even minor reductions in energy imports can have an enormous impact on the economy. Furthermore, the Japanese Corporate Goods Price Index (CGPI) was 10.2% in December 2022 (BOJ, January 16, 2023). With production costs higher than the CPI, Japanese businesses have absorbed increased costs themselves. One means to do this is to shrink the product size in order to avoid passing on the cost to customers or taking the cost on yourself by cutting into retained earnings. However, while the CPI might not therefore reflect the actual extent of inflation, this does not go unfelt by consumers and businesses given the strain on incomes/earnings.

Even if Japanese inflation was due to the oversupply of money, the scale of the intervention necessary to nullify inflation would be unmanageably large – even at 4%. While it is not feasible, realistic nor necessary for all private and government debt to be repaid in Japan to ‘balance the books’, the following explanation is illustrative at least in terms of conveying the magnitude of the issue. At the end of 2022, Japan’s combined government and private debt was approximately 2.26 quadrillion yen (BOJ, March 17, 2023) whilst its GDP was approximately 546.0 trillion yen (CAO, March 9, 2023). 4% of 2.26 quadrillion is 90.4 trillion which is approximately one sixth of Japanese GDP in yen. Thus, even if inflation could be addressed by raising rates, a cursory estimate of the scale of rate hikes would suggest that approximately one sixth of the Japanese economy would be rendered to debt service. 90.4 trillion yen constitutes approximately 78% of the nominal economic output of Tokyo (115.7 trillion), and more than the entire GDP output of the islands of Hokkaido, Kyushu, Okinawa and Shikoku combined (CAO 2019).

The BOJ therefore is not in a position to raise rates enough to curtail inflation owing to the following:

-

a)

Inflation in Japan appears to be cost-push, meaning the raising of interest rates in such a scenario only raises prices because the inflation is due to the undersupply of goods and materials, not oversupply of money.

-

b)

Even if inflation is demand-pull, the BOJ would likely have to raise rates to the point of triggering a depression in Japan as doing without one-sixth of GDP is impossible;

-

c)

In either case, it does not solve the issue of inflation in export markets, but could in fact worsen it given the extent of mutual exposure to risk between the Japanese economy and foreign ones.

Nonetheless, from the data above, we may conclude that the inflation Japan underwent in 2022 was not one that was beneficial to the economy because it was not caused by banks increasing their lending to the real economy for productive ends as is necessary for credit-based growth.

In an ostensible attempt to achieve the 'right kind' of inflation, the BOJ suppressed yields on 10-year government bonds below market levels for over six years to manage expectations over changes to interest rates long-term. However, the Japanese government now must increasingly intervene in the bond market to suppress the cost of domestic lending. If the cost of lending increases beyond a certain point, banks and other financial institutions will struggle to meet their obligations, and hence risk the triggering of a financial crisis. On the other hand, having to make increasingly sizeable interventions in the economy will place downward pressure on the yen and worsen the market dysfunction. In response, customers may seek to withdraw their deposits, triggering a financial panic.

This dynamic is further complicated by Japan's need to maintain a relative equilibrium in exchange rates. The country must import from abroad due to the scarcity of domestic energy resources, and hence has traditionally attempted to maintain growth based on a trade surplus. Thus, inflation in import and export markets impacts on economic decisions made by the BOJ in order to maintain exchange parities with key currencies and the Japanese financial institutions in order to hedge against the risk of these parities fundamentally changing. One example of this is inflation in key exports markets like the US. Though not the only cause, US inflation has worsened due to the enormous increases in the money supply, which increased by 40% over two years from 2020 to 2022 (Lynch, February 6, 2022). The US therefore has implemented quantitative tightening (QT) measures with raises in interest rates and tapering with a slowdown in the rate of asset purchasing carried out by the Federal Reserve (Sablik 2022; Jiang et al. 2023).

Changes in the value of the US dollar (USD), for example, are an obvious risk to the BOJ which must rely on demand for JGBs for the economy to function. Furthermore, Japanese banks have relied on the purchase of long-term securities and equities as a means to boost earnings while the BOJ maintained low interest rates (Economist, March 16, 2023). However, U.S. banks sustained $2 trillion of unrealized losses as a result of QT measures by April 2023 alone (Jiang et al. 2023), raising the issue of asset impairment on the books of these institutions both US and Japanese alike. One corollary to this is that the BOJ must now consider the possibility that Japanese investors will seek to repatriate capital to hedge against currency risk, which might justify the BOJ itself raising rates, despite the squeeze it would place on the average mortgage-paying Japanese citizen.

Raising rates, however, has its own attendant risks. Whether in the U.S., in Japan, or both, Japanese banks holding long-term assets will sustain unrealized losses, impacting on the entire Japanese economy. Furthermore, inflation unrelated to credit-based growth in export markets reduces the profit earned by Japanese exporters, as does a lower supply of production materials from import markets due to sanctions and trade restrictions. For these reasons, stabilizing the yen and ensuring liquidity for financial conditions are critical issues. However, the credibility of the yen is negatively impacted by inflation in key markets and domestic inflation unrelated to credit-based growth because maintaining this stability in exchange rates becomes impossible given the intricate and internationalized structure of production among Japanese businesses and their international partners across multiple currency zones.

For this reason, assessing the risk this kind of inflation places on the BOJ in its present dilemma necessitates an explanation of Japanese exposure to inflation/currency risk abroad as well as the efficacy of the responses of the BOJ and Japanese financial institutions to it. This is carried out in in the following section.

BOJ and global inflation

This section assesses the impact inflation has had on the BOJ and the Japanese economy as a whole in order to explain the answer to the question “what changed and why” with respect to the longevity of Japanese QE policy up to now. As stated, this involves not only understanding the limitations of cost-push inflation in Japan as a result of trade restrictions and sanctions, but also to understand how inflation in key international markets and the responses to them have affected the BOJ’s ability to handle its present dilemma with respect to its experiments with QE.

To do so, it is necessary to assess Japanese exposure to financial risk on an international level. Therefore, the analysis starts with an assessment of the changes in Japan’s current account balance to understand the changes in financial flows, as well as its correlation with the yen’s effective exchange rate. This is provided in Fig. 6, below.

Created by author using data from Ministry of Finance’s data for Japan’s “Balance of Payments (Historical data)” and BOJ’s database for the Effective Exchange Rate. *Calendar year. Effective Exchange Rate: 2020 = 100. For effective exchange rate, the mean of each calendar year was calculated as yearly average. Current account data for calendar year 2022 is from preliminary data

Japan’s primary income grew 38 per cent in 2021 and 33 per cent in 2022, the highest rate of growth in the dataset (1996–2022). In 2022, Japan’s current account recorded the largest primary income in the dataset also and, with import costs increasing 42 per cent, the largest trade deficit as well. Moreover, the increased import costs were not offset by foreign customers buying exported items—at least in terms of Japan’s trade balance—as exports grew by only 20 per cent in the same year.

However, Japan has come to rely on primary income as opposed to a national trade surplus as its production base has expanded overseas. Today, Japanese manufacturing comprises approximately 40 per cent of Japan’s income from direct investment, which is located primarily in Asia. The largest non-manufacturing industrial sector is wholesale and retail, closely followed by finance and insurance, which aside from Asia, are chiefly located in inflation-impacted countries in Europe and North America (BOJ, April 10, 2023). Thus, earnings from investment are essential to maintain a current account surplus, making Japan a highly internationalized economy which is vulnerable to the erection of trade barriers even in between jurisdictions outside of Japan such as China and the United States (Yamamoto and Toritani, 2023). The rising cost of goods as a result of tariffs or sanctions, then, has direct implications on the Japanese economy as does inflation in export markets.

Part of the increase in primary income is likely due to higher nominal returns from overseas investment by Japanese businesses, particularly from Japanese manufacturers in Asia less affected by soaring energy costs, as well as a weak yen. However, the trade deficit has caused Japan’s current account balance to substantially decline, and thus poses a risk to the Japanese economy if inflation is to be long-term. The composition of income from international investments sheds further light on this issue, and is provided in Fig. 7, below.

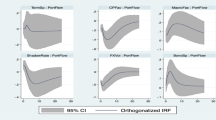

As Fig. 7 demonstrates , Japanese investors have chosen to retain earnings whether by reinvestment or dividend payments instead of investing in securities. This is highly likely to be in response to QT and tapering abroad, particularly in the U.S. Furthermore, the largest components of Japan’s primary income were reinvested earnings and “dividends and withdrawals from income of quasi-corporations.”

According to the Ministry of Finance, Japan’s financial account shows a decline in ownership of long-term debt securities amounting to 16.1 billion yen in 2021 and 12.7 billion yen in 2022, while short-term debt securities declined by 20 billion yen in 2020, 1.5 billion yen in 2021, and 10.1 billion yen in 2022 (Ministry of Finance 2023). In other words, in uncertain economic conditions, Japanese businesses have elected to hold onto earnings and sell foreign long-term debt securities. This is because Japanese investors, as the largest foreign holders of United States Treasuries (USTs) combined with Japan’s central bank, stand to sustain huge unrealized losses if the Federal Reserve raises interest rates. This likely also applies to international investors that have recently increased investment in Japan also. More to the point, with widespread speculation that the BOJ will at some point raise rates following the resignation of Governor Kuroda (Inujima, April 4, 2023), investors likely considered repatriating capital to Japan the safest option to hedge against foreign exchange risk. Furthermore, other countries have begun to sell USTs and expand frameworks of international trade that are non-dollar based (Russia Today, March 30, 2023), to which prudent investors in USTs and other dollar-denominated assets, will surely be attentive.

Indeed, many of these investors are Japanese as investment abroad has expanded as a result of the BOJ’s QE policies where low rates domestically caused investors to seek higher returns overseas. In 2021, Japan accounted for 10% of the foreign portfolio holdings of all U.S. securities, 17% for USTs, 6.3% for equities and 14.8% of all long-term debt (U.S. Department of the Treasury, March 15, 2023; April 28, 2023). However, recent data indicate a change of sentiment among investors, who are dumping U.S. securities, the majority of which is long-term, due to the rise in interest rates in the U.S. This is shown in Fig. 8, below.

Created by author using data from U.S. Department of the Treasury: “U.S. Liabilities to Foreigners from Holdings on U.S. Securities”, “Major Foreign Holders of Treasury Securities,” and “Foreign Portfolio Holdings of U.S. Securities as of June 30, 2022.” *Outstanding balance in June of stated year. 2022 data is preliminary. Year-on-year change calculated by author

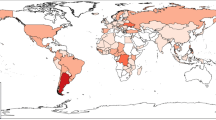

Japanese investors are also major holders of Australian, Brazilian, Dutch, French, German, Indian, New Zealand, Singaporean and United Kingdom sovereign debt, and have substantial holdings of foreign equities (Kondo and Sakai, Dec 7, 2022; Carson et al., March 29, 2023). Thus, if Japanese investors repatriate a significant portion of their capital due to elevated costs in hedging currency risk, demand for the yen will increase and possibly lead to an increase in the money supply. How this impacts on the Japanese economy does not solely depend upon on how this money is used and whether or not there are cheap resources for production, although important. Rather, the dumping of U.S. and European sovereign debt and financial assets runs the significant risk of triggering a financial crisis within these countries as a significant decline in demand in Western financial markets could lead to a string of insolvencies due to the elevating cost of credit. Needless to say, these are at present two key regions for Japanese exports and hence indispensable to the economy.

While the BOJ'S QE policy did not cause an increase in the domestic money supply, since 2013 it has inserted $3.4 trillion dollars of Japanese cash into foreign markets, with Japanese offshore investments worth more than two-third of its economy as a result of its YCC (Carson et al., March 29, 2023). However, the BOJ choosing to maintain low rates whilst the US and others raised them has caused financial institutions to short the yen and pocket the difference in rates. As a result, the JPY-USD exchange rate plummeted causing the BOJ to make interventions in the currency market in September and October of 2022 on an unprecedented scale. This is shown in Fig. 9, below.

Created by author using data from BOJ database and the Ministry of Finance’s “Foreign Exchange Interventions Operations.” * All data given for each quarter of each fiscal year since 1991. ** Data from Q4 of 2022 is not given as MOF’s Forex Intervention Operation did not provide the data at the time of collation. *** Forex intervention operations that involved a currency that was not the Japanese yen or U.S. dollar were excluded from the dataset. **** For forex intervention operations, positive values indicate the selling of JPY to purchase USD; negative values indicate the inverse

As shown in Fig. 9, the BOJ was faced with the choice of allowing the yen to depreciate by permitting the shorting of the yen to continue, or intervening in forex markets to sell U.S. dollars and hence potentially exacerbate inflation within one of its main markets for exports and foreign direct investment.

For this reason, however, large interventions in forex markets are unlikely to be something upon which the BOJ can rely as even if it were economically viable for Japan, it will likely become the cause of political friction between Japan and the U.S. if it continues. However, the BOJ must operate on the understanding that if the U.S. continues QT, investors will continue to short the yen. Thus, it is faced with two choices: maintain the YCC or maintain exchange rates. Maintaining its YCC and low yields would weaken the yen, elevate the cost of living for Japanese citizens, undermine Japan’s current account balance and fiscal budget, and risk bond market dysfunction. Maintaining exchange rates, at least with the US dollar, is obviously not risk free as it would entail either direct government intervention in currency markets or simply relaxing the YCC in order to prevent speculators from shorting the yen. However, this runs the risk of triggering a speculative attack on Japanese JGBs and causing balance-sheet problems for Japanese financial institutions.

The collapse of the UK gilt market, the insolvencies of Silicon Valley Bank and Credit Suisse, and the enormous losses recorded on the S&P500 and Nasdaq in 2022 alone, show that a financial crisis is by no means an unthinkable scenario in the near future but may already be unfolding. Thus, the BOJ will have to take seriously the risks that relaxing its YCC even further would have on international financial markets also to which Japanese institutions still have a high degree of exposure and dependence.

Japanese financial institutions have lowered investment in US securities and equities and have chosen to retain their earnings as Western nations have responded to inflation. With the BOJ hamstrung in what it can do with respect to its own domestic illiquidity issues, speculators have effectively shorted the yen for short-term profit. There is likely to be widespread recognition within financial circles that while the inflation party is in town, the BOJ cannot have its cake and eat it too. That is to say, it cannot maintain stable exchange rates with key currencies while remaining the only central bank with negative rates on short-term borrowing and ultra-low rates on everything else. Not only this, but despite its independence from the Ministry of Finance, the BOJ is nonetheless exposed to domestic pressure also, as an arm of the Japanese government, and thus must balance international pressures with domestic ones concerning the rising cost of living.

Of course, it is difficult to know exactly how much a reduction in demand for foreign securities among Japanese investors would be enough to trigger a financial crisis. However, this itself is a source of consternation for the BOJ which must respond but does not fully understand the repercussions of any given method for doing so. It is therefore likely to maintain its reactive role in the financial system and seek to make moderate changes while attempting to dovetail with other key economies such as the US.

Conclusion

Japan’s stated attempt at restoring productive economic growth since the collapse of its bubble economy in 1991 has entailed internationalizing/liberalizing the economy and relying on implementing low interest rates to overcome the country’s deflationary spiral. The long-term consequences of this have been a soaring government debt-to-GDP ratio. Low yields caused Japanese investors to turn their sights onto long-term securities and equity markets abroad while manufacturers relocated to Asia where production costs were cheaper, entailing structural changes to Japan’s economy.

Inflation unrelated to credit-based growth is problematic for the BOJ. Inflation caused by a rise in demand for investment in productive activities has been, ostensibly at least, Japan’s long sought-after goal since the collapse of the bubble economy. Inflation with little domestic demand undermines the BOJ’s twenty-year attempt at reviving the economy which depended on lowering rates to somehow raise demand as Japanese society ages and the population shrinks. Further, the multifaceted causes of inflation across different economies means that a coordinated response is highly unlikely. The BOJ has to rely on stabilizing foreign exchange rates by effectively depreciating the U.S. dollar or raising interest rates which will likely involve the dumping of sovereign debt such as USTs and hence worsening the decline in demand for securities from these economies. Due to this, the BOJ is in a highly fraught position as a result of long-term QE, as both raising and maintaining low rates runs the risk of incurring severe economic repercussions but it is impossible to know exactly what the consequences of certain responses to this problem will be too.

The BOJ will be forced to increase its purchasing of its own JGBs should rates stay low amidst inflation, exacerbating both the government deficit and bond market dysfunction, and causing losses on long-term securities that are held to maturation. Raising rates, however, will increase the extent of unrealized losses on long-term securities held at the central bank and Japan’s financial institutions, and risk triggering a financial crisis as demand for foreign bonds and securities weakens, drying up credit in highly unregulated derivatives markets where the extent of asset impairment and counterparty risk is unknowable, as Japanese investors reasonably look to protect themselves from exchange risk.

After the collapse of its bubble economy, Japan has redirected profit from its trade surplus to scale-up purchases of USTs so as to maintain a low yen to the dollar to support its exporting industries. To do so, the BOJ relied on bond issuance to cover the expenses and hence implemented a YCC policy in 2016 to prevent the price of JGBs from declining. With low interest rates, financial institutions carried out OTC derivatives transactions, and bought up foreign securities and equities. As a result, the BOJ now must buy up excess supply of Japanese sovereign debt in the market to maintain prices, meet the government’s budgetary requirements and to ensure that Japanese financial institutions continue these transactions.

However, Japanese banks have been unable to meet capital adequacy ratios and are reliant on the BOJ’s loose monetary policy as a means to service existing obligations. Global inflation has changed this dynamic, potentially presenting the BOJ with a means to increase domestic demand for Japanese securities and equities by moderately raising rates to convince investors to repatriate capital. However, cost-push inflation in Japan means that doing so would likely cause production costs to escalate further and hence exacerbate economic conditions. Furthermore, even if this were not the case, it is highly unlikely that the BOJ could know exactly how much they should raise rates by given the disordered nature of the global response to inflation and the seemingly haphazard manner in which the political economy is undergoing change.

Furthermore, raising interest rates would lower stock ratings, bond prices and make loans costlier. This would increase the extent of asset impairment on the balance sheets of many key investors in Japan and abroad. Servicing loans on government debt would increase too given that they are financed with JGBs, while unrealized losses both at the BOJ and its affiliated financial institutions could undermine the credibility of the yen. Obviously, a credit guidance mechanism may have prevented this situation from ever occurring but was never implemented despite its long history of success in Japan.

Nonetheless, for the reasons stated above, the BOJ finds itself in a precarious position with no apparently good options to choose from. It needs foreign demand for Japanese credit and goods. The BOJ must recognize the likelihood that demand for goods will dwindle in the key export markets of Europe and North America and that Japanese businesses will respond to this over time whether or not the BOJ does. Therefore, one option that remains for the Japanese economy is to seek demand for Japanese credit abroad in markets less affected by global inflation, such as those of emergent economies including the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) nations. However, doubts will remain as to its political feasibility given its diplomatic sensitivities, let alone economic.

Availability of data and materials

All datasets were compiled using official government sources. The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are also available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bank of Japan. 2001. “金融政策決定会合議事要旨” [Summary of monetary policy meeting], May 1, Bank of Japan. [https://www.boj.or.jp/mopo/mpmsche_minu/minu_2001/g010319.htm]. Accessed 13 Apr 2023.

Bank of Japan. 2007. “2006年度の金融市場調節” [Adjustments to financial markets of F.Y. 2006. Bank of Japan Financial Market Bureau. May 31, 2007. https://www.boj.or.jp/research/brp/ron_2007/ron0705a.htm. Accessed 10 Nov 2023.

Bank of Japan. 2013. “日本銀行が保有する国債の銘柄別残高 (2013年3月29日現在) ” [Japanese government bonds held by the Bank of Japan (as of March 29, 2013], March 29, Bank of Japan. https://www.boj.or.jp/statistics/boj/other/mei/release/2013/. Accessed 18 Apr 2023.

Bank of Japan. 2013. “「量的・質的金融緩和」の導入について” [About the introduction of ‘qualitative and quantitative monetary easing’], April 4, Bank of Japan. https://www.boj.or.jp/mopo/mpmdeci/mpr_2013/k130404a.pdf. Accessed 14 Apr 2023.

Bank of Japan. 2016. “「マイナス金利付き量的・質的金融緩和」の導入” [Introduction of “Quantitative and qualitative easing measures with negative interest], January 29, Bank of Japan. https://www.boj.or.jp/mopo/mpmdeci/mpr_2016/k160129a.pdf. Accessed 14 Apr 2023.

Bank of Japan. 2016. “金融緩和強化のための新しい枠組み: 「長短金利操作付き量的・質的金融緩和」” [A new framework to strengthen monetary easing: QQE with short and long-term interest rate controls], September 21, Bank of Japan. https://www.boj.or.jp/mopo/mpmdeci/mpr_2016/k160921a.pdf. Accessed 14 Apr 2023.

Bank of Japan 2022. “当面の金融政策運営について” [Update on financial policy operations], Decemember 20, 2022, Bank of Japan. https://www.boj.or.jp/mopo/mpmdeci/mpr_2022/k221220a.pdf. Accessed 9 Oct 2023.

Bank of Japan. 2023. “フェイルの発生状況 (2023年2月分) ” [Basic figures on fails (February 2023], March 10, Bank of Japan. [https://www.boj.or.jp/statistics/set/bffail/sjgb2302.pdf]. Accessed 18 Apr 2023.

Bank of Japan. 2023. “日本銀行が保有する国債の銘柄別残高 (2023年3月14日現在) ” [Japanese government bonds held by the Bank of Japan (as of March 14, 2023], March 14, Bank of Japan. https://www.boj.or.jp/en/statistics/boj/other/mei/release/2023/index.htm. Accessed 18 Apr 2023.

Bank of Japan. 2023. “2022年第4四半期の資金循環 (速報) [Flow of funds for fourth quarter of 2022 (Bulletin)], March 17, Bank of Japan. https://www.boj.or.jp/statistics/sj/sjexp.pdf. Accessed 14 Apr 2023.

Bank of Japan. 2023. “業種別・地域別直接投資: 2022年 (年次改訂値反映済) ” [Direct Investment by Region and Industry: 2022 C.Y. (Figures that reflect the annual revision)], April 10, Bank of Japan. [https://www.boj.or.jp/en/statistics/br/bop_06/bpdata/index.htm]. Accessed 18 Apr 2023.

Bank of Japan. 2023. “企業物価指数(2022年12月速報)” [Corporate Goods Price Index (December 2022 Bulletin), January 16, Bank of Japan. [https://www.boj.or.jp/statistics/pi/cgpi_release/cgpi2212.pdf]. Accessed 14 Apr 2023.

Bernanke, Ben S., & Vincent R. Reinhart. 2004. “Conducting monetary policy at very low short-term interest rates,” AEA Papers and Proceedings, May.

Brown, Ellen. 2013. The public bank solution: From austerity to prosperity. Baton Rouge LA: Third Millennium Press.

Brown, Ellen. 2019. Banking on the people: Democratizing money in the digital age. Washington D.C.: The Democracy Collaborative.

CAO. 2019. “県民経済計算 (平成23年度 - 令和元年度) (2008SNA、平成27年基準計数) <47都道府県、16政令指定都市分>” [Prefectural Economy Calculations (fiscal years 2001 to 2019) (2008 SNA, base year: 2015) <47 prefectures, 16 government-designated cities>], Cabinet Office, Government of Japan. [https://www.esri.cao.go.jp/jp/sna/data/data_list/kenmin/files/contents/main_2019.html]. Accessed 14 Apr 2023.

CAO. 2023. “国民経済計算 (GDP統計) ” [SNA (National Accounts of Japan)], Cabinet Office, Government of Japan. March 9. https://www.esri.cao.go.jp/jp/sna/menu.html. Accessed 14 Apr 2023.

Carson, Ruth, Masaki Kondo, & Michael Mackenzie. 2023. “A $3 trillion threat to global financial markets looms in Japan,” Bloomberg L.P. March 29, 2023. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-03-30/boj-s-ueda-could-shake-global-financial-markets-by-changing-kuroda-policy#xj4y7vzkg. Accessed 18 Apr 2023.

Economist. 2023. “The search for Silicon Valley Bank-style porfolios”. The Economist Newspaper. March 16. https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2023/03/16/the-search-for-silicon-valley-bank-style-portfolios. Accessed 18 Apr 2023.

E-stat. 2023. “消費者物価指数/2020年基準消費者物価指数/年報” [Consumer Price Index/Consumer Price Index with 2020 as base/Annual report],Official Statistics of Japan. March 31. https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/files?page=1&layout=datalist&toukei=00200573&tstat=000001150147&cycle=7&year=20220&month=0&tclass1=000001150150&stat_infid=000040028297&tclass2val=0. Accessed 14 Apr 2023.

Financial Services Agency. 2023. “「レバレッジ比率規制に関する告示の一部改正 (案) 」及び「G-SIB選定用指標開示様式 (第3の柱) の一部改正 (案) 」に対するパブリックコメントの結果等及び公表について” [On the results of public comments and official announcement regarding the “partial revision (draft) of the notice concerning leverage ratio regulation” and the “partial revision (draft) of the disclosure format for G-SIB selection indicators (pillar 3)”], Financial Services Agency, The Japanese Government. March 25. https://www.fsa.go.jp/news/r3/ginkou/20220325-2.html. Accessed 18 Apr 2023.

Gibney, Frank, ed. 1998. Unlocking the bureaucratic kingdom: Deregulation and the Japanese economy. Washington D.C.: Brookings Institute Press.

Huber, Joseph. 2017. Sovereign money: Beyond reserve banking. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Inujima, Akira. 2023. “上田日銀の前に守り: 国内投資家、金利上昇へ備え” [Protection before Ueda’s BOJ: Domestic investors prepare for potential interest rate rise], NIKKEI. April 4. https://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXZQOUB040LB0U3A400C2000000/. Accessed 18 Apr 2023.

Japan Post. 2023. “株式基本情報” [Basic information on stock], JAPAN POST HOLDINGS Co., Ltd. March 31, https://www.japanpost.jp/ir/stock/index10.html. Accessed 30 June 2023.

Jiang, Erica Xuewei, Gregor Matvos, Tomasz Piskorski, & Amit Seru. 2023. Monetary tightening and U.S. bank fragility in 2023: Mark-to-market losses and uninsured depositor runs? Working Paper, National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w31048.

Johnson, Chalmers. 1982. MITI and the Japanese miracle: The growth of industrial policy, 1925–1975. Stanford CA: Stanford University Press.

Kelton, Stephanie. 2020. The deficit myth: Modern monetary theory and the birth of the people’s economy. New York: PublicAffairs.

Kondo, Masaki, & Daisuke Sakai. 2022. “Japan’s life insurers are dumping foreign bonds at a record pace,” 2023 Bloomberg L.P. December 7. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-12-08/japan-s-lifers-are-dumping-foreign-bonds-at-a-record-pace#xj4y7vzkg. Accessed 18 Apr 2023.

Lynch, David J. 2022. “Inflation has Fed critics pointing to spike in money supply,” The Washington Post. February 6. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2022/02/06/federal-reserve-inflation-money-supply/. Accessed 18 Apr 2023.

Ministry of Finance. 2022. “わが国の財政事情” [Our country’s fiscal conditions], Budget Bureau, Ministry of Finance. December. https://www.mof.go.jp/policy/budget/budger_workflow/budget/fy2023/seifuan2023/04.pdf. Accessed 21 Apr 2023.

Ministry of Finance. 2023. “国際収支の推: 6s-4–1 金融収支[暦年・半期]” [Balance of Payments (Historical Data): Table 6s-4–1 Financial account [Annual/Half-yearly figures (Calendar Year)” Ministry of Finance, Japan. https://www.mof.go.jp/english/policy/international_policy/reference/balance_of_payments/ebpnet.htm. Accessed 18 Apr 2023.

Ministry of Internal Communications. 2020. “特別定額給付金の給付について” [About payment of the special fixed-allowance], Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Japan, October 1, 2020. https://warp.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/11560307/kyufukin.soumu.go.jp/ja-JP/index.html. Accessed 14 Apr 2023.

Miwa, Haruki. 2011. “日本の「デフレ」と金融政策” [Japanese deflation and monetary policy], 21seiki ajia-gaku kenkyu, 9: 43–57.

Morgan, Peter J. 2012. The role and effectiveness of unconventional monetary policy. In Masahiro Kawai, Peter J. Morgan, & Shinji Takagi (Eds), Monetary and Currency Policy Management in Asia. Cheltenham UK: Asian Development Bank Institute and Edward Elgar Publishing.

Nagai, Yoichi. 2013. "アベノミクス株高に潜む リフレ政策の光と影" [The Abenomics Stock Surge: The Light and Shadow of the Reflation Policy]. Nikkei. https://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXNASFL060MI_W3A200C1000000/. Accessed 10 Nov 2023.

Nikkei Shimbun. 2023. “消費者物価指数、22年12月4.0%上昇 41年ぶり上げ幅” [Inflation hit a 41 year high at 4.0% in December ‘22]. Nikkei. January 20, 2023. https://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXZQOUA19BA70Z10C23A1000000/. Accessed 13 Apr 2023.

Nikkei. 2023. Japan bond delivery failures highest since global financial crisis. Nikkei Inc. February 11. https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Markets/Bonds/Japan-bond-delivery-failures-highest-since-global-financial-crisis. Accessed 18 Apr 2023.

Pope, Chris G. 2021. Depoliticization and the changing boundaries of governance in Japan. Critical Policy Studies 16: 241–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2021.1941162.

Prime Minister’s Office of Japan. 2014. “アベノミクス「3本の矢」” [The three arrows of Abenomics], Cabinet Public Affairs Office, Cabinet Secretariat. https://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/headline/seichosenryaku/sanbonnoya.html. Accessed 13 Apr 2023.

Robinson, Gary. 2017. Pragmatic financialization: The role of the Japanese Post Office. New Political Economy 22 (1): 61–75.

Russia Today. 2023. Brazil and China sign pact to abandon dollar. RT, Autonomous Nonprofit Organization “TV-Novosti”, 2005–2023. March 30, https://www.rt.com/business/573852-brazil-china-abandon-dollar/. Accessed 18 Apr 2023.

Sablik, Tim. 2022. The Fed is shrinking its balance sheet. What does that mean? Econ Focus, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. https://www.richmondfed.org/publications/research/econ_focus/2022/q3_federal_reserve. Accessed 29 June 2023.

Sakai, Yoshihiro. 2006. Japan’s economy in the post-Koizumi era. Center for Strategic and International Studies, April 26, 2006. 1–2. Online at. Accessed 30 Aug 2023.

Sasaki, Jun’ichiro. 2010. “4章 東アジア; 1戦後日本経済の軌跡と「国際化」” [Chapter 4 East Asia: 1. The path of Japan’s postwar economy and ‘internationalization’], in Takumi Shimada (ed). “世界経済” [World Economy], Second revised edition, Tokyo: Yachiyo Publishers. Pp255–278.

Sekioka, Hideyuki. 2004. “拒否できない日本: アメリカの日本改造が進んでいる” [Japan that can’t say no: America’s Ongoing Remodeling of Japan]. Tokyo: Bungeishunjū.

Shirakawa, Masaaki. 2021. Tumultuous times: Central banking in an era of crisis. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Tax Commission. 2002. “平成15年度における税制改革についての答申: あるべき税制の構築に向けて” (Report on tax reform in fiscal year 2003: Toward the construction of an ideal tax system), Japan Tax Association. Japan. https://www.soken.or.jp/sozei/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/h1411_h15zeiseikaikaku.pdf. Accessed 30 June 2023.

Tanaka, Takayuki. 2009. “金融危機にどう立ち向かうか: 「失われた15年」の教訓” [How to address the financial crisis: Lessons from the lost 15 years], Tokyo: Chikuma.

Tomita, Mio. 2018. BOJ is top-10 shareholder in 40% of Japan’s listed compines. Nikkei Inc. June 27. https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/BOJ-is-top-10-shareholder-in-40-of-Japan-s-listed-companies. Accessed 14 Apr 2023.

TravelVoice. 2020 “政府、新型コロナ後の観光支援予算を閣議決定、国内旅行の需要喚起に1.7兆円、訪日客回復へ運休路線の再開を後押しも” [Government approves budget for tourism support after COVID-19, puts 1.7 trillion yen to stimulate demand for domestic travel, and also pushes for the resumption of cancelled air routes to bring back visitors to Japan], 2023 travel voice. April 7. https://www.travelvoice.jp/20200407-145894. Accessed 14 Apr 2023.

U.S. Department of the Treasury. 2023. Major foreign holders of Treasury securities (in billions of dollars. Department of the Treasury/Federal Reserve Board. March 15. https://ticdata.treasury.gov/Publish/mfh.txt. Accessed 29 June 2023.

U.S. Department of the Treasury. 2023. Foreign portfolio holdings of U.S. securities as of June 30, 2022. U.S. Department of the Treasury. April 28. https://ticdata.treasury.gov/resource-center/data-chart-center/tic/Documents/shlptab1.html. Accessed 29 June 2023.

Wada, Takahiko, Leika Kihara, & Junko Fujita. 2022. BOJ holds more than 100% of newly issued JGBs – report. Reuters. November 2. https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/boj-holds-more-than-100-of-newly-issued-10-year-jgbs-report. Accessed 18 Apr 2023.

Werner, Richard. 2003. Princes of the yen: Japan’s central bankers and the transformation of the economy. Oxon: Routledge.

Woodman, Andrew. 2017. Japan cuts corporate tax to spur growth, investments. Global Finance Magazine. December 14. https://www.gfmag.com/topics/asia-pacific/japans-corporate-tax-reform-abe-government. Accessed 29 June 2023.

Wray, L. Randall. 2015. Modern monetary theory, 2nd ed. Basingtoke UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Wray, L. Randall & Yeva Nersisyan. 2021. Has Japan been following modern monetary theory without recognizing it? No! And yes. Levy Economics Institute of Bard College. Working Paper No. 985.

Yamamoto, Kazuto, and Kazuo Toritani (Eds). 2023. “世界経済論: 変容するグローバリゼーション” [World Economics: The transformation of globalization], Second Edition, Kyoto: Minerva.

Acknowledgements

My gratitude to Professor Kazuo Toritani of Kyoto Women’s University, Professor Kazuto Yamamoto, Professor K. Ali Akkemik, and Professor Tatsushi Matsunaga, all of Fukuoka University.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pope, C.G. How inflation affects Japan’s “quantitatively eased” economy. ARPE 2, 8 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44216-023-00018-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44216-023-00018-w