Abstract

Background

Burnout among healthcare professionals is a serious problem with multiple consequences for the individuals and organizations affected. Thus, accessible and effective interventions are still needed to prevent and attenuate burnout. Self-compassion has recently been well supported in preventing and reducing burnout in various professions. Current research also demonstrated protective associations between self-compassion and well-being and/or psychological health indicators. Few studies are available on this topic during the COVID-19 pandemic or on healthcare workers from Quebec or Canada. Moreover, only a limited number of studies have looked at the associations of self-compassion with physiological variables.

This cross-sectionnal correlational study attempts to evaluate the association between self-compassion and burnout, among healthcare workers from Quebec (Canada) during the COVID-19 pandemic (n = 416 participants). Associations between their respective components are also tested. A secondary objective is to evaluate if self-compassion is also associated with a set of 38 biomarkers of inflammation (n = 83 participants), potentially associated with the physiological stress response according to the literature.

Participants meeting eligibility criteria (e.g.: residing in the province of Quebec, being 18 years of age or older, speaking French, and having been involved in providing care to COVID-19 patients) were recruited online. Participants completed the Occupational Health and Well-being Questionnaire, and some participated in a blood sample collection protocol.

Results

Results showed significant negative associations between self-compassion, exhaustion, and depersonalization, and a significant positive correlation with professional efficacy. Some self-compassion subscales (mindfulness, self-judgment, isolation, overidentification) were significantly negatively associated with certain biomarkers, even after controlling for confounding variables.

Conclusions

This study adds to the existing literature by supporting the association of self-compassion with burnout, and reveals associations between self-compassion and physiological biomarkers related to the stress response. Future research directions are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

1.1 Burnout amongst healthcare workers

Maslach et al. [1] defined burnout as a prolonged response to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors at work. According to Maslach [1], burnout has three dimensions, namely a state of emotional fatigue, detachment (i.e.: depersonalization, cynicism) as well as a feeling of ineffectiveness and/or incompetence. According to the Canadian Medical Association Journal, in 2021, physicians from all over the country reported being past the point of exhaustion, and declared unhealthy working conditions which included heavy workloads (60%) and long hours (56%) [2]. In Canada, five sectors showed burnout rates above the average of 35% following the pandemic, including workers in health and patient care (53%) [3]. Burnout or job stress are the most prevalent reasons why healthcare workers consider leaving their job (63.2%) [3]. The COVID-19 pandemic has challenged and continues to challenge workers from all around the world. In healthcare, this pandemic has brought many stressors, such as the risk of infection, isolation, economic concerns, new responsibilities, etc. [4]. Healthcare workers have experienced a wide range of mental health symptoms during this pandemic such as acute stress disorder, depression, anxiety, insomnia, burnout, and posttraumatic stress disorder [5]. A recent systematic review revealed it is difficult to determine the impact of the pandemic on the prevalence of burnout because many healthcare professionals were also experiencing these symptoms before the pandemic due to the grueling nature of this field of work [6]. However, the pandemic possibly contributed to exacerbating burnout symptoms by augmenting work-related stressors, both on an organizational level and individual. Shortage of resources (e.g.: lack of equipment, shortage of personal protection supplies), worry, and stigma surrounding COVID-19 are associated with burnout [6]. A cross-sectionnal study also demonstrated that younger age and female gender were predisposing factors for burnout and that the level of burnout varied significantly by site of practice and job category [7]. This study also reports factors susch as heavy workload, fear of contracting the disease or transmitting it to the family, as well as lack of staff support systems as potentially contributing to the elevation in burnout during the pandemic.

The consequences of professional burnout are multiple, on individuals physical and mental health (e.g.: impairments, risk of motor vehicle accidents or near-miss events, stress, disruptive behavior, mood disorders, substance abuse, suicidal ideations; Patel et al. [8]) and on organizations.Given the prevalence of burnout among healthcare workers and the significance of the consequences associated with it, it is paramount to document effective preventive and self-management strategies.

1.2 Self-compassion as a preventive strategy against burnout

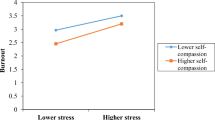

Recently, self-compassion has been studied in various populations, including healthcare workers, and may be an effective strategy for preventing and mitigating burnout [9,10,11,12,13]. Self-compassion is defined as the recognition that suffering, failure, and inadequacies are inherent in the human experience and that everyone, including oneself, deserves compassion [14]. Self-compassion consists of three basic components: being gentle and understanding of oneself rather than overly self-critical and judgmental, seeing one’s personal experiences as part of the human experience rather than isolating oneself, and being attentive to one’s difficult thoughts and emotions rather than over-identifying with them [14].

More specifically with healthcare workers, self-compassion has shown promise in improving the quality of life [15], protecting against burnout [15] and buffering the relationship between perceived stress on burnout [16]. It is also reported that self-compassion is associated with less burnout symptoms among healthcare personnel from Lebanon [17]. Replicating results regarding the negative association between self-compassion and burnout in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic in healthcare personnel seems highly pertinent and could help support self-compassion interventions in burnout prevention.

1.3 Obstacles in the study of self-compassion

Even if studies depict self-compassion as a promising strategy to prevent and reduce burnout, certain obstacles are present in the studies and limit their impact. Current literature often report the total self-compassion score of the Self-Compassion Scale [14] in association with burnout. This approach has been criticized, mainly because of the inclusion of “positive” subscales, related to the capacity for self-compassion (i.e.: self-kindness, mindfulness, common humanity) and the inclusion of “negative” subscales, related to self-criticism (i.e.: self-criticism, over-identification, isolation). When the total score is used, it becomes difficult to identify the contribution of each subscale [18].

Previously cited studies on self-compassion also document mainly the psychological aspects of burnout. Only a few studies examined the association between self-compassion and the physiological stress response, wich can lead eventually to burnout. Exploring these associations could support self-compassion interventions given the severity of the consequences of physiological stress on the body and eventually provide insight into the mechanisms underlying these effects. Thus far, regarding self-compassion, these mechanisms have been hypothesized and tested in a vary limited number of studies and results remain inconsistent. It has been hypothesized that self-compassion may act on the stress response through the inhibition of the sympathetic nervous system [19,20,21], the inhibition of the Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal axis [20, 22,23,24] or through the stimulation of oxytocin production [25, 26]. Studies are often correlational and relied on internal validity with laboratory-induced stressors (ex.: Trier social stress test) [20] and only included one or two biomarkers [21], although a multi-modal and combined approach would possibly be more helpful and reliable since biomarkers can be influenced by various individual and environmental factors [27]. There is also a need for better methodological approach in biomarkers research: standardized procedures, cost-effective measures, clinical significance, etc. [27].

2 Aims of the study

The principal objective of this study is to evaluate the associations between self-compassion and burnout among healthcare workers from Quebec (Canada) during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study seeks to gain a more complete perspective on the relationship between self-compassion and burnout by analyzing each construct’s components rather than the total score alone. In light of the literature on the subject, the hypotheses concerning the expected results are as follows: negative correlations between positive self-compassion subscales (i.e.: self-belief, common humanity and mindfulness) and exhaustion and depersonalization; positive correlations between positive self-compassion subscales (i.e.: self-belief, common humanity and mindfulness) and professional efficacy; positive correlation between self-compassion negative subscales (i.e.: sel-judgment, isolation and overidentification) and exhaustion and depersonalization; and negative correlation between self-compassion negative subscales (i.e.: sel-judgment, isolation and overidentification) and professional efficacy. A secondary objective is to document the association between self-compassion and a set of 38 biomarkers of inflammation, associated with the physiological stress response. Given the existing literature on the subject, a negative association between self-compassion and burnout is hypothesized. Regarding the association between self-compassion and biomarkers, negative correlations are expected with biomarkers of inflammation.

3 Methods

3.1 Participants

This article was reported following the Strobe guidelines for cross-sectional correlational study [28]. This study is part of a larger research project involving 576 front-line healthcare workers in the province of Quebec during the COVID-19 pandemic, with 416 complete observations. Of these, 86 participants agreed to participate in the biological component of the study and to provide a blood sample in addition to completing the Occupational Health and Well-being Questionnaire—OHWQ [29]. Participants were from a variety of occupations (physicians, nurses, orderlies, respiratory therapists, managers) in Quebec hospitals and long-term care centers (e.g.: CHSLDs). Participants were recruited in urban and rural areas (i.e.: Quebec, Montreal, Mauricie, Saguenay-Lac Saint-Jean).

3.2 Procedure

The protocol of this study has already been published, providing details on the methodology used [30]. Participants were recruited online via emails and virtual and social networks and had to meet eligibility criteria (i.e.: reside in the province of Quebec, be 18 years of age or older, speak French, have been involved in providing care to COVID-19 patients). Data collection took place during the COVID-19 pandemic in Quebec, from March to the end of June 2021. The survey was self-administered online, and blood samples were collected by qualified nurses following a standardized protocol. Blood samples were analyzed and blood serum from each participant was processed through the Milliplex MAP Human Cytokine/Chemokine Magnetic Bead Panel [30]. The 38 biomarkers are presented in Table 1.

3.3 Materials

This article focuses on the results of two questionnaires included in the Occupational Health and Well-being Questionnaire (OHWQ) [29], the Self-Compassion Scale [14], and the Maslach Burnout Inventory [31]. Participants’ sociodemographic information was also gathered (i.e.: age, sex, education) and later used in the analysis as confounding variables.

The Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) is a measure of self-compassion that assesses a person’s ability to show kindness and understanding to themselves, even in adverse situations [14]. The questionnaire consists of 26 items to be rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale. This scale is composed of six subscales: self-belief, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identification. The SCS calculates a total self-compassion score as well as subscale scores. The total score is analyzed according to the following scale: 1.0–2.49: low self-compassion, 2.5–3.5: moderate self-compassion and 3.51–5.0: high self-compassion. Regarding its psychometric qualities, the instrument's internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was good for its subscales (0.74 to 0.89) and excellent for its overall score (0.94). The convergent validity with other indicators of well-being is good (e.g., satisfaction with life, subjective happiness, etc.). The SCS questionnaire has been validated in French-speaking populations, between the ages of 15 and 83 [32].

The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) measures burnout and its three dimensions, emotional exhaustion, cynicism/depersonalization, and sense of professional efficacy (satisfaction with accomplishments) [31]. The questionnaire only allows for the calculation of scores on the three subscales by adding up the corresponding items. The MBI consists of 22 items to be rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale. Internal consistency, again measured with Cronbach's alpha, is satisfactory for the burnout and professional efficacy scales, but unsatisfactory (< 0.70) for the depersonalization and loss of empathy scale [33].

3.4 Statistical analysis

First, descriptive statistics were performed on certain participants’ characteristics. All statistical analyses were done using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS; Version 29) with a significance level of 5%. Missing data was removed from the analysis.

Objective 1: To test whether the level of self-compassion of an individual is associated with the level of the 3 components of burnout, correlational analysis was performed. The normality of the data was tested by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (N = 416). The distribution of the data was found to be non-normal, which led to the use of non-parametric statistical tests. The Spearman correlation coefficient was calculated. A subsequent partial correlation analysis with confounding variables (age, sex, and education) was done. Linear regressions between self-compassion components and burnout components were performed to determine if self-compassion is a predictor of burnout, and relevant basic assumptions were met.

Objective 2: To explore the association between self-compassion subscales and the 38 biomarkers measured, correlational analysis was performed. The normality of the data was tested by the Shapiro–Wilk test. The distribution of the data was found to be non-normal, which led to the use of non-parametric statistical tests. The Spearman correlation coefficient was calculated. A subsequent partial correlation analysis with confounding variables (age, sex, and education) was done.

4 Results

4.1 Participants’ characteristics

Participants who failed to complete one or more questions in the SCS or the MBI were removed from the sample. Participants were predominantly women. 416 participants completed the questionnaire (72.73% of 572 participants) and had no missing data. 86 participants completed both the questionnaire and biological measures (83 after removing extreme data). Participants were aged between 19 and 67 years old, the mean age being 40.29. Participants’ characteristics are presented in Table 2.

5 Objective 1

5.1 Associations between self-compassion and burnout components

Results showed that the level of self-compassion (total score) is significantly negatively associated with exhaustion and depersonalization, and positively associated with professional efficacy, as presented in Table 3. When adjusting for confounding variables, the results were still significant and in the same direction.

5.2 Associations between self-compassion components and burnout components

Results showed that the level of self-compassion is significantly associated with burnout components except for common humanity with exhaustion and depersonalization, as presented in Table 4. When adjusting for confounding variables, results were still significant and in the same direction except for the associations between depersonalization and self-kindness and mindfulness, and professional efficacy and self-judgment.

5.3 Self-compassion as a predictor of burnout

5.3.1 Exhaustion

The results of the simple linear regression model were significant, F(6, 415) = 23.576, p < 0.001. Results are presented in Table 5.

5.3.2 Depersonalization

The results of the simple linear regression model were significant, F(6, 415) = 7.601, p < 0.001. Results are presented in Table 6.

5.3.3 Professional efficacy

The results of the simple linear regression model were significant, F(6, 415) = 10.489, p < 0.001. Results are presented in Table 7.

6 Objective 2

6.1 Associations between self-compassion subscales and biomarkers

Results showed that some self-compassion subscales were significantly associated with certain biomarkers, even when adjusting for confounding variables. Significant correlations are presented in Table 8.

7 Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine associations between self-compassion and burnout, including their respective components. A second objective was to verify if self-compassion is associated with a panel of 38 inflammatory biomarkers related to the physiological stress response in healthcare workers in Quebec (Canada), during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The results of this study regarding the association between self-compassion and burnout are aligned with the existing literature on this topic. As aforementioned, studies often showed a negative association between self-compassion and burnout [10, 11, 17, 34, 35]. The strongest associations were found between self-compassion and emotional exhaustion and self-efficacy, as in Hashem and Zeinoun [17]. Some studies even found a negative association between burnout and self-compassion components [10]. Results from studies showed significant associations between negative components of self-compassion, such as over-identification, isolation and self-judgment, and exhaustion, which was also the case in this study. In addition, this study re-establishes that self-compassion is a significant predictor of burnout, as noted previously in a similar cross-sectional study by Atkinson et al. [9] in a sample from the Veterans Affairs mental health staff. This contributes to evidence supporting the protective role of self-compassion against burnout in healthcare workers. In light of these results and previous literature, interventions aimed at developing self-compassion as a coping strategy can be beneficial.

Interestingly, the results in this study regarding self-compassion scores and burnout scores were very similar to those found by Hashem and Zeinoun [17] in their healthcare sample from Lebanon. It is pertinent to reflect on the fact that despite difficult circumstances and high levels of exhaustion, healthcare workers still presented high self-efficacy or a sense of professional efficacy. The literature suggested that healthcare professionals often have a loss of professional efficacy along with high exhaustion and depersonalization [36]. In this sample and at the moment of data collection, it did not seem to be the case. Many factors can influence professional accomplishment scores. For example, a study identified that the risk to experience low professional efficacy was influenced by experience (i.e.: residents vs physicians), antecedents of psychological difficulties before the pandemic, social avoidance, and safety behaviors [37]. It is possible to hypothesize that the overall perception of the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., political, societal, etc.) may also play a role in feelings of self-efficacy at this time. Although COVID-19 affected healthcare personnel and exposed them to stress, moral distress, and other physical and psychological risks, it may have been at this point that they felt particularly needed and recognized, often described as “heroes” [38]. However, this hypothesis needs to be explored in future research, as although healthcare workers were generally referred to positively during this period, some still experienced negative comments [39]. A recent study also explored the associations between the contruct of the sense of coherence and burnout components [40] and found meaningful associations. It can be hypothesized that elements from the cultural and organizational context might have had a role to play to foster the sense of coherence (i.e.: meaningfulness, comprehensibility, manageability) within healthcare workers and, consequently, their sense of professional accomplishment. It is also important to note that although self-efficacy seems to be a positive coping mechanism in the short term, it may lead to energy depletion and disengagement over time when this strategy is over-utilized and accompanied by exhaustion and cynicism [41].

In this study, some self-compassion subscales (mindfulness, self-judgment, isolation, overidentification) were significantly negatively associated with certain biomarkers, even after controlling for confounding variables. These correlations were relatively low. Self-judgment was the subscale correlated with the most biomarkers (i.e.: 10). The 38 biomarkers in this study were initially selected because there is evidence in the literature of associations between these biomarkers and various mental health outcomes. These markers are also involved in inflammatory and immune responses. These results should be interpreted with caution, given their exploratory nature and the type of analysis used. At present, the results help to direct future research into the potential use of biomarkers to better understand the effects of self-compassion and its mechanisms of action.

8 Strengths, limitations, and future research

This study adds to the existing literature on self-compassion and burnout by suggesting associations between the components of these two variables and the protective power of self-compassion on burnout. This study stands out by having analyzed a broad set of 38 biomarkers of inflammation rather than a few targeted biomarkers. This approach is encouraged in recent biomarkers research within psychiatry [27]. Conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, this study also adds to the literature on a population that was impacted by this historic event namely healthcare workers.

However, this study has limitations. The number of participants in the biomarker arm was relatively small, which limits the statistical power and increases the potential for type 2 errors. It is possible that the study had a selection bias, meaning that participants differed significantly from non-participants in terms of self-compassion and burnout (e.g., participants working in better conditions had more time to participate). In addition, biomarker studies have some inherent risks (e.g., sample temperature, and collection time). Burnout and self-compassion were measured by self-report. The French version of the MSC has a social desirability bias [33]. The MBI presents an American view of burnout and heterogeneous results for correlations for the personal accomplishment scale [42, 43]. Another limitation concerns the research correlational design. As it is a cross-sectional study, it is impossible to identify causality within the results, so they should be interpreted carefully. Indeed, longitudinal data collection and qualitative data could have been very relevant and led to a better understanding of the trajectory of the variables over time.

Although this study does not evaluate the effectiveness of self-compassion interventions on the basis of the current results, it nevertheless helps to confirm the negative association between self-compassion and burnout. In view of the results, it seems appropriate to encourage future research in this field to demonstrate the effectiveness of the interventions, while using questionnaires appropriately. The authors also hope, through this study, to raise awareness of self-compassion as a preventive strategy against burnout. In the context of new Quebec legislation for the prevention of psychosocial risks in the workplace, effective, scientifically-backed individual and organizational interventions and strategies are needed more than ever. Future research could investigate healthy ways of developing a sense of professional accomplishment in self-compassion interventions as a preventive factor against burnout, potentially through the enhancement of a sense of coherence.

9 Conclusions

In conclusion, this study contributes to the advancement of self-compassion research. Having access to healthcare workers during a global pandemic revealed to be a unique research opportunity for a better understanding of self-compassion and burnout during difficult times. It is imperative to recognize the important work of all workers and staff who have been impacted by COVID-19. Even under difficult circumstances, this study reflects their impressive sense of professional accomplishment. It is hoped that this study stimulates discussion and research in this area, and ultimately deepens our understanding of self-compassion and its physical and psychological implications for burnout.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Laboratoire en santé et bien-être au travail de l’Université Laval under the direction of MT, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of MT.

Abbreviations

- MBI:

-

Maslach Burnout Inventory

- SCS:

-

Self-Compassion Scale

- OHWQ:

-

Occupational Health and Well-being Questionnaire

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

References

Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job Burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52(1):397–422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397.

Duong D, Vogel L. Overworked health workers are ‘past the point of exhaustion.’ Can Med Assoc J. 2023;195(8):E309–10. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.1096042.

Canada Life, “New research shows more than a third of all Canadians reporting burnout,” 2022. https://www.canadalife.com/about-us/news-highlights/news/new-research-shows-more-than-a-third-of-all-canadians-reporting-burnout.html. Accessed 5 Jan 2024.

Franc-Guimond J, Hogues V. Burnout among caregivers in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic: insights and challenges. Can Urol Assoc J. 2021;15(6 S1):S16–9. https://doi.org/10.5489/CUAJ.7224.

Chigwedere OC, Sadath A, Kabir Z, Arensman E. The impact of epidemics and pandemics on the mental health of healthcare workers: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(13):6695. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18136695.

Gualano MR, et al. The burden of burnout among healthcare professionals of intensive care units and emergency departments during the covid-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18158172.

Jalili M, Niroomand M, Hadavand F, Zeinali K, Fotouhi A. Burnout among healthcare professionals during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2021;94(6):1345–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-021-01695-x.

Patel R, Bachu R, Adikey A, Malik M, Shah M. Factors related to physician burnout and its consequences: a review. Behav Sci. 2018;8(11):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs8110098.

Atkinson DM, Rodman JL, Thuras PD, Shiroma PR, Lim KO. Examining burnout, depression, and self-compassion in veterans affairs mental health staff. J Altern Complement Med. 2017;23(7):551–7. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2017.0087.

Duarte J, Pinto-Gouveia J, Cruz B. Relationships between nurses’ empathy, self-compassion and dimensions of professional quality of life: a cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;60:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.02.015.

Durkin M, Beaumont E, Hollins Martin CJ, Carson J. A pilot study exploring the relationship between self-compassion, self-judgement, self-kindness, compassion, professional quality of life and wellbeing among UK community nurses. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;46:109–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2016.08.030.

Lapa TA, Madeira FM, Viana JS, Pinto-Gouveia J. Burnout syndrome and wellbeing in anesthesiologists: the importance of emotion regulation strategies. Minerva Anestesiol. 2017;83(2):191–9. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0375-9393.16.11379-3.

Neff KD, Knox MC, Long P, Gregory K. Caring for others without losing yourself: an adaptation of the mindful self-compassion program for healthcare communities. J Clin Psychol. 2020;76(9):1543–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23007.

Neff KD. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Ident. 2003;2(3):223–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309027.

Dev V, Fernando AT, Consedine NS. Self-compassion as a stress moderator: a cross-sectional study of 1700 doctors, nurses, and medical students. Mindfulness. 2020;11(5):1170–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01325-6.

Abdollahi A, Taheri A, Allen KA. Perceived stress, self-compassion and job burnout in nurses: the moderating role of self-compassion. J Res Nurs. 2021;26(3):182–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987120970612.

Hashem Z, Zeinoun P. Self-compassion explains less burnout among healthcare professionals. Mindfulness. 2020;11(11):2542–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01469-5.

Muris P, Otgaar H. The process of science: a critical evaluation of more than 15 years of research on self-compassion with the self-compassion scale. Mindfulness. 2020;11(6):1469–1482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01363-0.

Arch JJ, Landy LN, Brown KW. Predictors and moderators of biopsychological social stress responses following brief self-compassion meditation training. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;69(2016):35–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.03.009.

Bluth K, et al. Does self-compassion protect adolescents from stress? J Child Fam Stud. 2016;25(4):1098–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0307-3.

Breines JG, Thoma MV, Gianferante D, Hanlin L, Chen X, Rohleder N. Self-compassion as a predictor of interleukin-6 response to acute psychosocial stress. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;37:109–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2013.11.006.

Arch JJ, Brown KW, Dean DJ, Landy LN, Brown KD, Laudenslager ML. Self-compassion training modulates alpha-amylase, heart rate variability, and subjective responses to social evaluative threat in women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;42:49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.12.018.

Pace TWW, et al. Effect of compassion meditation on neuroendocrine, innate immune and behavioral responses to psychosocial stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(1):87–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.08.011.

Rockliff H, Gilbert P, McEwan K, Lightman S, Glover D. A pilot exploration of heart rate variability and salivary cortisol method participants. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2008;5(3):132–9.

Uvnäs-Moberg K, Petersson M. Oxytocin, a mediator of anti-stress, well-being, social interaction, growth and healing. Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2005;51(1):57–80. https://doi.org/10.13109/zptm.2005.51.1.57.

Uvnäs-moberg K, Handlin L, Petersson M. Self-soothing behaviors with particular reference to oxytocin release induced by non-noxious sensory stimulation. Front Psychol. 2015;5:1–16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01529.

Scarr E, et al. Biomarkers for psychiatry: the journey from fantasy to fact, a report of the 2013 CINP think tank. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;18(10):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijnp/pyv042.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010.

Truchon M, Gilbert-Ouimet M, Zahiriharsini A, Beaulieu M, Daigle G, Langlois L. Occupational health and well-being questionnaire (OHWQ): an instrument to assess psychosocial risk and protective factors in the workplace. Public Health. 2022;210:48–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2022.06.008.

Gilbert-Ouimet M, et al. Predict, prevent and manage moral injuries in Canadian frontline healthcare workers and leaders facing the COVID-19 pandemic: protocol of a mixed methods study. SSM Ment Heal. 2022;2:100124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmmh.2022.100124.

Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach burnout inventory. In: Zalaquett CP, Wood RJ, editors. Evaluating stress: a book of resources, scarecrow. Lanham: Scarecrow Education; 1997. p. 191–218.

Kotsou I, Leys C. Self-compassion scale (SCS): psychometric properties of the French translation and its relations with psychological well-being, affect and depression. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(4):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152880.

Langevin V, Boini S, François M, Riou A. Maslach burnout inventory (MBI). Références en santé au Trav. 2012;131:157–9.

Sanabria-Mazo JP, et al. Mindfulness-based program plus amygdala and insula retraining (MAIR) for the treatment of women with fibromyalgia: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Clin Med. 2020;9(10):1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9103246.

Olson K, Kemper KJ. Factors associated with well-being and confidence in providing compassionate care. J Evidence-Based Complement Altern Med. 2014;19(4):292–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156587214539977.

Al-Otaibi T, et al. Determinants, predictors and negative impacts of burnout among health care workers during COVID-19 pandemic. J King Saud Univ Sci. 2023;35(1):102441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2022.102441.

Lasalvia A, et al. Levels of burn-out among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic and their associated factors: a cross-sectional study in a tertiary hospital of a highly burdened area of north-east Italy. BMJ Open. 2021;11(1): e045127. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045127.

Cox CL. ‘Healthcare Heroes’: problems with media focus on heroism from healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Med Ethics. 2020;46(8):510–3. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2020-106398.

Shan W, Wang Z, Su MY. The impact of public responses toward healthcare workers on their work engagement and well-being during the Covid-19 pandemic. Front Psychol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.949153.

Stoyanova K, Stoyanov DS. Sense of coherence and burnout in healthcare professionals in the COVID-19 Era. Front Psychiatry. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.709587.

Yuan Z, et al. Burnout of healthcare workers based on the effort-reward imbalance model: a cross-sectional study in China. Int J Public Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/ijph.2021.599831.

Kristensen TS, Borritz M, Villadsen E, Christensen KB. The copenhagen burnout inventory: a new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work Stress. 2005;19(3):192–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370500297720.

Lourel M, Gueguen N. Une méta-analyse de la mesure du burnout à l’aide de l’instrument MBI. Encephale. 2007;33(6):947–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.encep.2006.10.001.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript. However, the original research project and data collection was funded by Ministry of National Defense of Canada, le Réseau intersectoriel de recherche en santé de l’Université du Québec (RISUQ) and le Réseau de recherche en santé des populations du Québec (RRSPQ). No funding was received for this article specifically.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Literature search, data analysis and writing of this article was primarily done by CB, as a part of her thesis. Data collection and original research project was done by MGO and MT. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study uses data collected previously by MT and MGO. All procedures performed in the original data collection for this study were in accordance with ethical standards and approval was granted by the ethics committee of the ‘Centre intégré universitaire de santé et de services sociaux de la Capitale-Nationale’ in Quebec, Canada. Informed consent was obtained originally during the data collection, meaning that participants that answered questionnaires and provided blood samples were fully aware of the study’s purposes, risks and benefits. All participants were over 18 years old.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bégin, C., Gilbert-Ouimet, M. & Truchon, M. Self-compassion, burnout, and biomarkers in a sample of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional correlational study. Discov Psychol 4, 75 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-024-00192-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-024-00192-9