Abstract

The mental health well-being of elderly individuals in Bangladesh is often neglected at home and nationally. Non-medical interventions become a crucial mental health solution for the population, with outdoor recreational activities, identified as an influential determinants. This study, conducted in Dhaka, the capital city of Bangladesh, aims to explore the relationship between outdoor recreational activities and mental well-being, utilizing the Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) approach. Interviewing 514 older adults, the study considered four dimensions: park activities, social involvement, sports participation, and outdoor hobbies and tourism. The final model indicates that all four dimensions significantly and positively impact the mental well-being of elderly individuals, with sports participation showing the greatest positive effect. Together, these dimensions account for 75.12% of the variance in mental well-being. The nature of the relationship suggests that an increase in outdoor recreational activity corresponds to improved mental well-being. This paper reinforces the idea that engagement in outdoor activities contributes to positive mental health outcomes, aligning with the new physical activity guidelines set by the World Health Organization (WHO) that emphasize the positive relationship between outdoor recreations and life satisfaction. This study strongly recommends people should actively engage in outdoor recreational activities. Additionally, it urges government and private organizations to prioritize the maintenance of public open spaces as essential contributors to the mental well-being of the older population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Mental well-being is a critical factor influencing longevity and healthy aging, ranking as the third most common cause of years lived with disability globally [1]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), mental well-being empowers individuals to better cope with life's challenges, handle stress, recognize their abilities, learn and work effectively, and actively contribute to society [1]. Despite its significance, many studies predominantly focus on the physical dimension of health, overlooking the crucial mental well-being aspect for the elderly [2].

The prevalence of elderly individuals living alone has increased globally, with a rise from 11 to 15% for women and 6% to 8% for men between 1990 and 2010 [3]. Living alone in later life is associated with depressive symptoms, significantly impacting mental health and life satisfaction. Loneliness, particularly among the elderly, has emerged as a serious problem in Bangladesh [4]. Additionally, the overall prevalence of depressive (57.9%), stress (59.7%), and anxiety (33.7%) symptoms in the adult population of Bangladesh is higher than in many comparable countries, with concerns that these figures may be even higher for the elderly [5].

Mental disorders contribute to over 12% of the total global cost of disease, calculated using disability-adjusted life years [6]. Notably, mental health problems are positively correlated with mortality in 72% of cases among the elderly, leading to increased medical and therapy-related expenses [7]. Approximately 450 million individuals worldwide are affected by neuropsychiatric disorders, with over 15 million in Bangladesh suffering from at least one type of mental disorder [8]. Shockingly, only 0.44% of Bangladesh's national health budget is allocated to mental health, and less than 0.11% of the population has access to free essential psychotropic medications [8].

Given the limited social support, motivation, knowledge, and resources available for the elderly, it becomes crucial to explore non-medical interventions for their mental well-being [9]. Engaging in outdoor recreational activities such as park visits, tours, playing sports, and social interactions has consistently been associated with various health benefits, including improved cognitive functioning, reduced risk of cardiovascular disease, and enhanced physical fitness [10,11,12]. Oxford reference defines outdoor recreation as leisure activities that provide pleasure, taking place in open spaces, often in natural settings, with a focus on recreation rather than competition [13].

Outdoor recreational activities have been shown to have positive effects on mental health and life satisfaction across various age groups, including the elderly [14]. Recent guidelines from the USA and WHO emphasize the mental health benefits of walking, recommending at least 30 min of walking to maintain a better mental state [2]. Studies have consistently underscored the importance of outdoor activities, such as walking, gardening, and sports participation, in promoting physical health and mobility among the elderly, ultimately contributing to higher life satisfaction and improved mental well-being [15, 16]. In addition to the physical and cognitive advantages, exposure to nature and social interactions during outdoor activities offers psychological benefits, including reduced stress and sadness, elevated self-worth, and a reinforced sense of identity [17,18,19]. Leisure time spent outdoors has been recommended for promoting good mental health, reducing stress and depressive symptoms, and fostering feelings of happiness [15, 16].

Given the inadequacy of government budget for mental health issues in Bangladesh and the increasing loneliness among the elderly, non-pharmacological interventions, particularly outdoor recreational activities, are proposed to enhance mental health conditions among this population [9]. It is important to note that most studies linking mental well-being and outdoor recreational activities have been conducted in developed countries [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. Therefore, it is crucial to assess the holistic impact of outdoor recreational activities on mental well-being before formulating recommendations in the context of Bangladesh.

While previous research has explored specific outdoor activities like park visits, social or religious involvement, and outdoor physical activities in relation to mental well-being [19, 25,26,27], there is a need for a more comprehensive understanding of the overall impact of outdoor interactions on mental health in elderly individuals. Life satisfaction, a key component of subjective well-being, offers valuable insights into individuals’ perceptions and experiences of their mental state and overall quality of life [28]. Recognizing the intimate connection between mental health and quality of life, assessing life satisfaction alongside mental health can provide crucial information to identify factors with a positive effect on both. This approach enhances the capacity and confidence of policymakers to rely on the findings of this paper [29]. Thus, this study intends to estimate the relation between outdoor recreational activities (park visits, sports participation, social interaction, hobbies and tourism) to mental well-being of elderly people of Bangladesh.

1.1 Conceptual framework

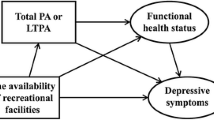

This study endeavours to conceptualize a comprehensive framework, depicted in Fig. 1, to explore the intricate connections between outdoor recreational activities and the mental well-being of the elderly. Recognizing the multitude of dimensions within outdoor recreational activities, this framework draws upon established theories from existing studies. Empirical research consistently emphasizes the pivotal role of strong social connections, active engagement, community participation, and social support networks in mitigating depression, anxiety, and loneliness [30,31,32]. These factors have demonstrated a substantial contribution to better mental health and enhanced life satisfaction, particularly among the elderly. Wood et al. [33] highlights the positive impact of exposure to green spaces on psychological well-being [33]. Moreover, studies by Brown et al. (2020) and Jewett et al. [34] underscore how sports participation fosters self-esteem, stress management, and life satisfaction [34, 35]. Parker [36] and Skałacka & Błońska [37] suggest that outdoor hobbies alleviate isolation, promote relaxation, and imbue life with purpose [36, 37].

In light of these findings, this study considers four dimensions of outdoor recreational activities—social connections, active engagement, exposure to green spaces, and sports participation—as they have been consistently shown to impact mental well-being. To assess the applicability of these pathways in the context of Bangladesh, the study incorporates these dimensions into a Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) framework. Additionally, acknowledging the influence of income and education on various dimensions of outdoor activities, especially hobbies, tourism, social involvement, and sports participation, this research introduces education and income as mediating variables in the model (Fig. 1).

2 Methodology

2.1 Study design and source of data

This was a cross-sectional study that used primary data; collected from (1st March to April 2022) using a pre-structured questionnaire and analyzed the data using different statistical modelling along with SEM application. The data were collected through face-to-face interview techniques.

2.2 Study area and population

The target population of this study were the older people (aged 50 and above) people of Dhaka city who visit public parks frequently for outdoor recreations such as exercise, social involvements, and outdoor games (e.g., football, pillow passing, volleyball etc.) excluded those who were doing business or begging. Dhaka city is one of the four largest megacities in the world [38] with more than 21.7 million population and an agglomeration of people from all parts of the country. Dhaka city has several public parks where people from every economic stratum come [39]. Elderly peoples are more likely to gather in those parks in the morning as it is the best place to have a walk or exercise or other outdoor activities, therefore, it was easier for the researchers to reach those older people who were actively involved in the parks. Purposively five big and famous parks were selected from the capital city: Ramna Park, Chandrima Uddan, Dhanmondi Lake Park, Gulshan Lake Park, and Suhrawardy Uddan. These parks are highly visited by the city people, one of the reasons is Dhaka is very congested city and people always search for open spaces. Additionally, people from diverse background gather within those parks which makes those as suitable places for collecting data from various types of elderly individuals.

2.3 Sampling procedure and data collection technique

The sample size for this study was determined using Cochran’s (1977) formula for a population proportion of 50%. A total of 543 respondents were selected with a 98% confidence level and a 5% margin of error. Ultimately, data from 514 respondents were collected and analyzed.

The data collection technique employed was a random walk, identified as the most suitable method for cluster-based surveys in previous studies [40, 41]. The survey was conducted between March 1 and April 23, 2022, by a team of ten trained members. The team underwent a full-day training session on data collection procedures, ethics, and consent under the supervision of the lead researcher, a panel of experts from Khulna University, and the project supervisor. The sample size was allocated based on selected survey areas, with one park randomly chosen from five pre-selected parks to initiate data collection. Each Park was divided into blocks, and the team commenced data collection from the main entrance. In cases where a park or university had multiple main entrances, one entrance was randomly selected to begin the process.

The team followed a clockwise direction for 30 s, collecting data from the nearest respondent meeting all inclusion criteria. This process continued until the predetermined quota was met. Inclusion criteria for participants were Bangladeshi residents aged over 50 years willing to provide the required data, while exclusion criteria included individuals who were blind, deaf, or had mental or physical illnesses. Non-cooperative respondents were marked as non-responses, and the team proceeded with the same technique for universities.

2.4 Questionnaire development

Two scales were used to measure the mental well-being of the respondents. The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) is used to measure life satisfaction and Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS) to measure mental well-being. Both questionnaires were first translated into Bangla and then again transformed into English to maintain meaning and consistency. Researchers translated the questionnaire to ask the questions to the participants. The questionnaires were pre-tested before finalizing them for data acquisition.

2.4.1 Dependent variable

Two dependent variables were considered for this study. First, Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS) and second, the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) scale[42]. The WEMWBS scale has 14 different questions with 5 option Likert scale regarding subjective well-being and psychological functioning and all the questions were positively articulated no reverse questions were found. The final score was calculated by summing all the scores [1,2,3,4,5] of 14 questions, therefore the range of this scale is 14 to 70, where 14 represents the worst condition of mental wellbeing and 70 is the highest (Supplementary Table 1).

This WEMWBS scale's validity has received extensive confirmation across various regions. In the United Kingdom, Tennant (2007) reported a Cronbach alpha score of 0.89 for a student sample and 0.91 for a population sample [43]. Similarly, in Scotland, Stewart-Brown (2009) observed high interitem correlations, affirming the scale's robustness [44]. In Denmark, Koushede (2019) and in India (which is similar in social setting to Bangladesh) Singh & Raina (2020) recommended this scale for measuring perceived mental well-being, further validating its efficacy [45, 46].

Second, the SWLS which was the combinations with five different 5 questions with 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 5 to 35. Highest the value shows much life satisfaction and the lowest means poor life satisfaction. (Supplementary Table 2). The scale under consideration has been favourably endorsed in prior research as a complementary tool. While it may not comprehensively capture overall life satisfaction, it serves to integrate and weigh other psychological domains, particularly mental well-being [47]. The scale’s applicability extends globally, with validations conducted in diverse settings such as Hong Kong [48], Iran [49] and Bangladesh [50]. Notably, both studies recommend the use of this scale for measuring life satisfaction in a specific direction.

2.4.2 Independent variables

Independent variables of this study encompass different ranges of outdoor recreational activities which are most common in the context of Bangladesh. There are questions are structured following previous studies which suggest different ways of measuring outdoor recreational activities [51,52,53]. The questionnaire involves four different dimensions of outdoor recreation those are park engagement [53], social participation [52], sports participation [51] and involvement in hobbies and tourism. All of these are important elements for measuring the indirect intensity of physical outdoor recreation whereas direct intensity measures include pedometers, accelerometers, heart monitors etc. [54, 55]. Table 1 represents short descriptions of those independent variables.

2.5 Statistical analysis

A total of 543 respondents were initially interviewed for this study. However, 29 datasets (out of 543) were disregarded due to missing or improper data, resulting in a final dataset of 514 responses for comprehensive analysis. The statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS (v.26) and AMOS (v.22), employing Structural Equation Modelling (SEM). SEM was chosen for its ability to build a comprehensive model predicting latent variables with observed variables, facilitating path analysis to illustrate specific connections between dependent and independent variables. Additionally, SEM allows for the calculation of mediatory effects based on respondents' backgrounds [56].

In this study, mental wellbeing served as the dependent variable, while park activities, social involvements, sports participation, outdoor hobbies, and tourism were considered independent variables. Age, income, marital status, sex, and education were included as exogenous variables. In the proposed model variables with no statistically significant (p < 0.05) association with any of the construct or a factor loading score (< 0.5) were excluded from the final model. Consequently, sex and marital status were disregarded in the final model.

To identify potential variance between means of different categories, independent sample t-tests, followed by one-way ANOVA, were conducted using SPSS. The internal validity and consistency of the scales used were assessed, with Cronbach alpha scores for SWLS and WEMBWS measuring (0.860 and 0.870), respectively. Additionally, the Average Inter Item Correlation (AIC) test was performed, yielding scores above 0.20 for both scales, affirming the established internal validity and consistency of the scales for this study.

3 Results

In Table 2, 85.01% of respondents are male. Although there's no significant difference in WEMWBS score between genders, females scored higher in SWLS scale. Dominant age group is 50–60 years (67.32%); they significantly outscored others in WEMWBS scale while all age groups performed equally in SWLS.

Out of total respondents, 71.79% respondents were married and score higher in both scales compared to divorced/widowed. Those who completed higher secondary or higher education scored significantly better on both scales, meaning education has a deep connection with mental well-being. Most of the respondents have monthly income ranged 20,001 to 50,000 BDT, however Monthly income do not have significant association with mental wellbeing scales.

Table 3 presents respondents who have outdoor hobbies (such as hiking, gardening etc.) (SWLS = 21.94; WEMWBS: 49.69; p≤ 0.001) or have taken up any new outdoor hobbies recently (SWLS: 22.22; WEMWBS: 49.91; p≤ 0.001) scored significantly better in both two scales than their counterparts. Tour participation (SWLS = 21.93; WEMWBS: 50.09; p≤ 0.001) and considering a nature-oriented one-day tour for their next outing (SWLS = 21.41; WEMWBS: 49.29; p≤ 0.001) also have a positive relationship with both SWLS and WEMWBS scores. Balancing participation in one-day tours with other commitments does not have any significant differences on the SWLS scale (SWLS = 20.39; p = 0.067) but it shows different results on the other scale (WEMWBS: 48.60; p≤ 0.015). Hence, the findings suggest that individuals who engage in outdoor hobbies, participate in one-day tours, and effectively manage time for tours amidst other life commitments exhibit a more favourable mental condition, coupled with heightened life satisfaction.

Table 4 presents that active members of any social club (SWLS = 21.76; WEMWBS: 49.67; p≤ 0.001) or religious group (SWLS = 20.30 p = 0.042; WEMWBS: 49.23; p≤ 0.001) scored relatively higher than their respective counterparts. Though community organization involvement does not have any significant differences in WEMWBS score (WEMWBS: 47.96; p = 0.215) but scored better on the SWLS scale (SWLS = 21.15; p≤ 0.001). Participating in a voluntary social group (SWLS = 21.93; WEMWBS: 49.91; p≤ 0.001) and charity work (SWLS = 23.31; WEMWBS: 51.24; p≤ 0.001) both have positive relations with the mental well-being of the participants. Therefore, it is evident that individuals who were more engaged in various social activities demonstrated higher scores in both scales, indicating a positive association between social activities and enhanced mental wellbeing.

Those who visit parks one time or more in a day scored higher on both two scales. Post-hoc LSD result suggests that those who often visit the park one (SWLS = 21.85; WEMWBS: 50.43; p≤ 0.001) or more times a day (SWLS = 23.77; WEMWBS: 53.48; p≤ 0.001) scored significantly higher than those who visits rarely or sometimes (Table 5). Going to the park with family or friends or spending more than 60 min in a park has a linear positive relationship with both two scales. Visiting parks for taking health treatment or performing mobile activities have positive relationships with mental wellbeing scores. Those who often take health therapy (SWLS = 23.26; WEMWBS: 51.83; p≤ 0.001) or perform mobile activities (SWLS = 22.98; WEMWBS: 51.74; p≤ 0.001) in the park have significantly scored higher on both two scales than other two groups (Table 5).

In Table 6 identifies that those who rarely participate in outdoor sport (SWLS = 17.34; WEMWBS: 45.84; p≤ 0.001) scored significantly lower in both two scales than the other two groups where those who often plays outdoor sport for more than 60 min scored (SWLS = 24.31; WEMWBS: 53.25; p≤ 0.001) significantly better than their counterparts. Participated in outdoor sports competitions or events have linear positive relations with mental wellbeing scores on both two scale. While using sports clubs often have (SWLS = 23.33; WEMWBS: 52.26; p≤ 0.001) significant difference between the other two groups. Therefore, it is evident that respondents who visited parks more frequently and engaged in various park activities demonstrated significantly better mental wellbeing. Similarly, outdoor sports participation also exhibited a positive effect. Notably, this positive effect appeared to follow a linear trend, suggesting that as the frequency of park activities or outdoor sports increased, so did the level of mental wellbeing.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed using AMOS 24 and all the factors with loading scores (> 0.50) were considered fit for the model. CFA results indicate that proposed model fits perfectly for running further analysis and construct SEM because all the values are found under an acceptable threshold. The CMIN/df = 4.048; CFI = 0.922; GFI = 0.927; TLI = 0.908; RMSEA = 0.078 and SRMR = 0.051 (Supplementary Table 3). Composite reliability test score for this model ranged from 0.825 to 0.911 which is above the benchmark[57] and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values for this model were also above the recommended level of 0.50 [58] (Supplementary Table 4). Thus, this Structure Equation model found fit for this study and perfectly capable of predicting factors behind enhanced mental well-being.

The most influential factor for determining mental wellbeing, measured by the WEMWBS scale, with a substantial factor loading of 0.86 and a significance level of p = 0.001. When it came to hobbies and tourism construct, having an outdoor hobby (factor loading = 0.79, p≤0.001) and participating in tours (factor loading = 0.79, p≤ 0.001) emerged as the strongest predictors. For sport participation, the most robust predictor was participating in sports events or competitions, with a factor loading of 0.91 and p≤ 0.001. Social involvement was best predicted by engagement in charity works (factor loading = 0.81, p = 0.002). Interestingly, exogenous variables like age and marital status did not exhibit significant effects on mental health, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Thus, the WEMWBS scale emerges as the most influential variable for mental wellbeing, with the SALS scale performing as a subscale. Having a hobby and participating in one-day tours emerged as the most significant predictors within the hobbies and tourism construct. Meanwhile, participating in competitive sports and engaging in charity work were identified as the strongest predictors of outdoor sports participation and social involvement construct respectively.

Moreover, direct and indirect association among latent variables was shown by standardized beta coefficients (β). Specifically, park activities (β = 0.285; p≤ 0.001), sport participation (β = 0.349; p≤ 0.001), social participation (β = 0.212; p≤ 0.001), and involvement in hobbies and tourism (β = 0.244; p≤ 0.001) all exhibited direct effects on mental health. Sports participation demonstrated the strongest effect on mental well-being, and given the positive nature of this relationship, it can be inferred that mental well-being improves with an increased frequency of sports participation. In fact, all the paths indicated a positive relation to mental well-being. Therefore, it is evident that outdoor recreational activities have a substantial positive effect on the mental wellbeing of the elderly population in Bangladesh (Fig. 2).

Additionally, income and education, as exogenous variables, were correlated with both social capital and mental health. Income displayed a positive correlation with outdoor hobbies and tourism (β = 0.211; p≤ 0.001) and sports participation (β = 0.309; p≤ 0.001). Conversely, education displayed positive correlations with both social involvement (β = 0.232; p≤ 0.001) and outdoor hobbies and tourism (β = 0.158; p≤ 0.001), but it exhibited a negative correlation with sport participation (β = − 0.192; p≤ 0.001). Notably, education displayed the strongest correlation with social involvement. It's important to note that any paths lacking a p-value < 0.05 were omitted from the final model. The goodness of fit indices for this model were as follows: CMIN/df = 3.718; CFI = 0.932; GFI = 0.916; RMSEA = 0.073; SRMR = 0.0501.

4 Discussion

Previous studies have consistently indicated a strong connection between mental well-being and engagement in outdoor recreations, encompassing both structured and unstructured experiences [59,60,61,62,63]. Our study employed a Structured Equation Model (SEM) to further explore these relationships and found that several outdoor factors namely, park activities, sport participation, social participation, and involvement in hobbies and tourism positively influence the mental well-being of elderly individuals.

Univariate analysis uncovered that individual engaging in outdoor hobbies such as camping, gardening, and hiking, as well as those who recently adopted new hobbies, displayed higher levels of mental well-being. Prior studies have similarly identified that outdoor hobbies, which facilitate physical activity, social interaction, and emotional expression, contribute to individuals feeling happier [22, 64]. Pomfret et al. [65] argued that outdoor recreational activities not only benefit mental well-being but also contribute to better physical and mental balance, thereby enhancing resilience [66]. Building on this, Ryu and Heo [67] asserted that engaging in outdoor hobbies enables the elderly to handle risks more effectively and manage anxiety [65].

Elderly people who participated in one-day tours or expressed interest in nature-oriented tours for their next outing demonstrated higher levels of mental well-being, aligning with previous studies [67,68,69,70,71,72]. Tourism, particularly nature-based tourism, serves as a means for stress reduction and alleviating feelings of loneliness. In densely populated countries like Bangladesh, where cities like Dhaka are heavily crowded, nature-based tours or the mere intention to embark on such tours can significantly benefit the mental health of the elderly. Furthermore, there is evidence suggesting that tourism enhances physical and cognitive functioning [67]. Moreover, in Bangladesh the isolation and loneliness are increasing among elderly population [4]. Thus, government or private organizations emphasize on enhancing the practice of outdoor hobbies or tourism can elevate mental wellbeing countering isolation and depression [73, 74].

[75]Consistent with findings from previous studies [76, 77], the present study also reveals that involvement in social clubs or neighboring organizations is associated with enhanced mental well-being. Participation in such groups exposes individuals to their community and like-minded peers, offering opportunities for social interaction that effectively combats depression and loneliness [75]. A similar positive impact on mental well-being was observed for individuals engaged in charity or religious work. Cohen and Johnson [78] argued that participation in charity and religious activities provides individuals with spiritual peace and motivates them to find happiness in meeting the needs of others, thereby contributing to their own mental well-being [79].

While some studies have indicated a link between religious beliefs and mental depression and anxiety [78, 80,81,82,83], the context in Bangladesh, where a majority of the population holds religious beliefs, likely fosters mutual bonding through religious practices, resulting in a twofold positive effect on mental health [84, 85]. Potočnik and Sonnentag [72] suggested that elderly people should be made aware of the countless benefits of social and religious activities to better acknowledge a purpose in life, leading to improved mental health and well-being [86].

The study's model underscores the significant positive impact of park activities and visits on the mental well-being of elderly individuals. Regular Park visits, longer stays in parks, and engagement in physical park activities all demonstrate a linear, positive relationship with mental well-being. This aligns with previous research indicating that park visits expose individuals to green environments, which positively boost their mental well-being [25, 87,88,89,90,91,92]. The World Happiness Report 2021 also highlighted the benefits of visiting parks with close companions, providing an opportunity to escape the regular work environment, refreshing individuals, and leading to better self-perceived happiness [93]. These positive effects may be attributed to the opportunities created by park visits, including social interactions, physical activities, emotional and experience sharing, and access to health therapies, all of which play a crucial role in reducing stress and enhancing life satisfaction and mental well-being [94, 95]. Parks in urban areas, when equipped with opportunities for interaction, exercise, green spaces, and quality time, can serve as comprehensive solutions to mental well-being problems.

This study identified outdoor sport participation has the strongest positive effect on the mental health which is consistent with numerous previous studies [96,97,98]. This correlation can be explained by the fact that sports participation increases the likelihood of interacting with new people and forming new groups, which is highly beneficial for mental well-being [99]. Additionally, team sports are inherently interactive and enjoyable, leading to reduced stress and overthinking [100,101,102,103,104,105]. Gilleard and Higgs [106] emphasized the importance taking sports as a lifestyle for elderly individuals to lead a happy life [107].

Several prior studies have also highlighted the antidepressant properties of outdoor sports, demonstrating that regular participation in outdoor sports is associated with reduced signs of depression [106, 108, 109]. Moreover, competitive sports can lead to adrenaline boosts, which may reduce depressive symptoms and enhance mental well-being [110,111,112].

Therefore, it is safe to conclude that outdoor recreational activities, specifically frequent park visits, social and religious involvement, outdoor hobbies and tourism, and sports participation, enhance the mental well-being of elderly people. This underscores the importance of open spaces in urban areas. In the case of Bangladesh, where there is a lack of adequate mental illness curation centres, public open spaces can play a vital role. Moreover, they can serve as non-medical interventions for mental well-being, reducing the burden on hospitals. It is highly recommended to maintain public open spaces, especially in crowded cities like Dhaka. Additionally, these open spaces can be a lifeline for poor people both young and older adults who cannot afford formal treatment, as they can take advantage of these areas to engage in recreational activities and maintain better mental well-being.

5 Policy recommendations

-

Allocate more land for the creation of parks, gardens, and green pathways, particularly in densely populated cities like Dhaka. Ensure equitable distribution of these spaces across neighborhoods.

-

Equip parks with facilities for physical activity (sporting courts, walking paths), social interaction (community centers, benches), and relaxation (green spaces, water features). Promote the use of parks for picnics, outdoor events, and gatherings.

-

Design and offer free or subsidized programs for elderly individuals, including nature walks, hiking excursions, and gardening workshops. Partner with local organizations and NGOs to facilitate these programs.

-

Provide opportunities for sports participation through dedicated senior leagues, open gym sessions, and accessible equipment in parks. Consider offering low-impact sports options like badminton, walking groups, or tai chi classes.

-

Offer grants or tax breaks to private organizations providing outdoor hobby classes or nature-based tours for seniors. Promote affordable travel packages focused on scenic destinations within Bangladesh.

-

Launch public awareness campaigns highlighting the connection between mental well-being and engagement with nature, parks, and social activities.

-

Train healthcare providers on the importance of outdoor activities for mental health and equip them with resources to recommend such activities to their elderly patients.

6 Strengths and limitations

The major strength of this study lies in its holistic approach, encompassing not only four distinct dimensions of outdoor recreational activities but also variables that gauge the extent of involvement in those dimensions. Additionally, the inclusion of the SWLS scale alongside WEMWBS contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of mental well-being. The study's incorporation of direct, indirect, and mediatory effects within a single model provides a complete picture of the relationship between outdoor recreational activities and mental health outcomes.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, the cross-sectional design restricts the study's ability to make long-term projections, and the variation in the effects of outdoor recreational activities on mental well-being over time remains unexplored. Future research with a longitudinal approach could address this limitation. Secondly, the focus on Dhaka city limits the generalizability of the study's findings to other parts of Bangladesh. Expanding the study to include diverse regions would enhance its representativeness.

Lastly, the study lacked data on potential confounding factors such as job satisfaction, family status, disease presence, and dietary habits. Addressing these variables in future research within the context of Bangladesh would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between outdoor recreations and mental well-being.

7 Conclusions

This study reinforces the vital role of outdoor activities in boosting mental well-being among elderly individuals. From park visits and sports participation to hobbies and nature excursions, engaging in outdoors recreational activities fosters social interaction, physical activity, and a sense of purpose, all of which combat loneliness, depression, and anxiety. In densely populated cities like Dhaka, Bangladesh, where dedicated mental healthcare facilities are scarce, public open spaces become even more crucial, offering accessible, non-medical interventions for improving the mental well-being of both young and elderly populations. Therefore, prioritizing the creation and maintenance of green spaces in urban areas is essential for fostering a happier and healthier society. Future research should incorporate follow-up studies to explore the impact of emotional support and physical function maintenance on mental well-being, providing a clearer understanding of the contributing factors. Additionally, conducting longitudinal studies would enable a comprehensive examination of how these variables influence mental well-being over time, offering insights into the changing dynamics of these relationships.

Data availability

Data were collected through face-to-face interview and preserved by the corresponding author. The data are, however, available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Aliyas Z. Physical, mental, and physiological health benefits of green and blue outdoor spaces among elderly people. Int J Environ Health Res. 2021;31(6):703.

Kerr J, Marshall S, Godbole S, Neukam S, Crist K, Wasilenko K, et al. The relationship between outdoor activity and health in older adults using GPS. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9(12):4615.

Nation United. World Population Prospects—Population Division—United Nations. https://population.un.org/wpp/default.aspx?aspxerrorpath=/wpp/%20Publications/Files/WPA2017Report.pdf. Accessed 14 Jan 202.

Rahman MS, Rahman MA. Prevalence and determinants of loneliness among older adults in Bangladesh. Int J Emerg Trends Soc Sci. 2019;5(2):57.

Al BMH, Sayeed A, Kundu S, Christopher E, Hasan MT, Begum MR, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of the adult population in Bangladesh: a nationwide cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Health Res. 2022;32(4):850.

WHO. WHO Expert Consultation on rabies, third report. Geneva: WHO; 2018.

Schulz R, Drayer RA, Rollman BL. Depression as a risk factor for non-suicide mortality in the elderly. Biol Psychiatry. 2002. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01423-.

Hasan MT, Anwar T, Christopher E, Hossain S, Hossain MM, Koly KN, et al. The current state of mental healthcare in Bangladesh: part 1—an updated country profile. BJPsych Int. 2021;18(4):78.

Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW, Hunkeler E, Harpole L, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2002;288(22):2836.

Keniger LE, Gaston KJ, Irvine KN, Fuller RA. What are the benefits of interacting with nature? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10:913.

Gump BB, Matthews KA. Are vacations good for your health? The 9-year mortality experience after the multiple risk factor intervention trial. Psychosom Med. 2000;62(5):608.

Klesges RC, Eck LH, Hanson CL, Haddock CK, Klesges LM. Effects of obesity, social interactions, and physical environment on physical activity in preschoolers. Health Psychol. 1990;9(4):435.

Outdoor recreation - Oxford Reference [Internet]. https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100257403. Accessed 25 Feb 2024.

Burns J. A southern alliance for research and innovation in mental health. Afr J Psychiatry. 2009;12(3):181.

Godbey G. Leisure in your life: an exploration. State College: Venture Publishing; 1999.

Coleman D, Iso-Ahola SE. Leisure and health: the role of social support and self-determination. J Leis Res. 1993;25(2):111.

Sugiyama T, Leslie E, Giles-Corti B, Owen N. Associations of neighbourhood greenness with physical and mental health: do walking, social coherence and local social interaction explain the relationships? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(5):e9.

WHO Team. Mental Health Atlas 2020. Geneva: WHO Publication; 2021.

Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social ties and mental health. J Urban Health. 2001;78(3):458.

Biddle S. Physical activity and mental health: Evidence is growing. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:176.

Beyer KMM, Kaltenbach A, Szabo A, Bogar S, Javier Nieto F, Malecki KM. Exposure to neighborhood green space and mental health: evidence from the survey of the health of Wisconsin. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(3):3453.

Coventry PA, Brown JVE, Pervin J, Brabyn S, Pateman R, Breedvelt J, et al. Nature-based outdoor activities for mental and physical health: systematic review and meta-analysis. SSM Population Health. 2021;16:100934.

Tyson P, Wilson K, Crone D, Brailsford R, Laws K. Physical activity and mental health in a student population. J Mental Health. 2010;19(6):492.

Arsović N, Đurović R, Rakočević R. Influence of physical and sports activity on mental health. Facta Universitatis Series Phys Educ Sport. 2020. https://doi.org/10.22190/FUPES190413050A.

Orstad SL, Szuhany K, Tamura K, Thorpe LE, Jay M. Park proximity and use for physical activity among urban residents: associations with mental health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(13):4885.

Barnett PA, Gotlib IH. Psychosocial functioning and depression: distinguishing among antecedents, concomitants, and consequences. Psychol Bull. 1988;104(1):97.

Bélanger M, Gallant F, Doré I, O’Loughlin JL, Sylvestre MP, Abi Nader P, et al. Physical activity mediates the relationship between outdoor time and mental health. Prev Med Rep. 2019;16:101006.

Diener E, Wirtz D, Tov W, Kim-Prieto C, Choi D, won, Oishi S, et al. New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc Indic Res. 2010;97(2):143.

Warburton DER, Nicol CW, Bredin SSD. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. CMAJ. 2006;174:801.

Ozbay F, Johnson DC, Dimoulas E, Morgan CA, Charney D, Southwick S. Social support and resilience to stress: from neurobiology to clinical practice. Psychiatry. 2007;4(5):35–40.

Kim E, Cho BY, Kim MK, Yang YJ. Association of diet quality score with the risk of mild cognitive impairment in the elderly. Nutr Res Pract. 2022;16(5):673.

Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(2):227.

Wood L, Hooper P, Foster S, Bull F. Public green spaces and positive mental health—investigating the relationship between access, quantity and types of parks and mental wellbeing. Health Place. 2017;48:63.

Jewett R, Sabiston CM, Brunet J, O’Loughlin EK, Scarapicchia T, O’Loughlin J. School sport participation during adolescence and mental health in early adulthood. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(5):640.

Brown DR, Wang Y, Ward A, Ebbeling CB, Fortlage L, Puleo E, et al. Chronic psychological effects of exercise and exercise plus cognitive strategies. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995. https://doi.org/10.1249/00005768-199505000-00021.

Parker MD. The relationship between time spent by older adults in leisure activities and life satisfaction. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr. 1996;14(3):61.

Skałacka K, Błońska K. Physical leisure activities and life satisfaction in older adults. Act Adapt Aging. 2023;47(3):379.

Top 10 largest megacities in the world 2022. NEOM NEWS. https://neomsaudicity.net/top-largest-megacities-2017/. Accessed 7 Feb 2023

Islam M, Mahmud A, Islam S. Open space management of Dhaka City, Bangladesh: a case study on parks and playgrounds. Int Res J of Environ Sci. 2015;4(12):118–26.

WHO. World Health Organization vaccination coverage cluster surveys: reference manual. Geneva: WHO; 2018.

Satta A, Puddu M, Venturini S, Giupponi C. Assessment of coastal risks to climate change related impacts at the regional scale: the case of the Mediterranean region. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017;24:284.

Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsem RJ, Griffin S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49(1):71.

Tennant R, Hiller L, Fishwick R, Platt S, Joseph S, Weich S, et al. Health and quality of life outcomes the Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): development and UK validation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-5-63.

Stewart-Brown S, Tennant A, Tennant R, Platt S, Parkinson J, Weich S. Internal construct validity of the Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): a Rasch analysis using data from the Scottish health education population survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:15.

Koushede V, Lasgaard M, Hinrichsen C, Meilstrup C, Nielsen L, Rayce SB, et al. Measuring mental well-being in Denmark: validation of the original and short version of the Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS and SWEMWBS) and cross-cultural comparison across four European settings. Psychiatry Res. 2019;271:502.

Singh K, Raina M. Demographic correlates and validation of PERMA and WEMWBS scales in Indian adolescents. Child Indic Res. 2020;13(4):1175.

Pavot W, Diener E. Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychol Assess. 1993;5(2):164.

Sachs J. Validation of the satisfaction with life scale in a sample of Hong Kong university students. Psychologia. 2004;46(4):225.

Bayani AA, Koocheky AM, Goodarzi H. The reliability and validity of the satisfaction with life scale. J Iran Psychol. 2007;3(11):259–60.

Sagar MH, Karim AKMR. The psychometric properties of satisfaction with life scale for police population in Bangladeshi culture. Int J Soc Sci. 2014;28(1):24–31.

Sport England. Explanation of sports participation indicators—creating a lifelong sporting habit. Sport England. 2018;1(1).

Howrey BT, Hand CL. Measuring social participation in the health and retirement study. Gerontol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny094.

Walker JT, Mowen AJ, Hendricks WW, Kruger J, Morrow JR, Bricker K. Physical activity in the park setting (PA-PS) questionnaire: reliability in a California Statewide sample. J Phys Act Health. 2009;6:S97.

Mood DP, Jackson AW, Morrow JR. Measurement of physical fitness and physical activity: fifty years of change. Measurement Phys Educ Exercise Sci. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1080/10913670701585502.

Godbey G. Outdoor recreation, health, and wellness: understanding and enhancing the relationship. SSRN Electron J. 2011. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1408694.

Thakkar JJ. Structural equation modelling: application for research and practice (with AMOS and R). In: Kacprzyk J, editor. Studies in systems decision and control. Singapore: Springer; 2020.

Hair JF, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Mena JA. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J Acad Market Sci. 2011;40(3):414–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0261-6.

Fornell C, Larcker DF. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. J Market Res. 1981;18(3):382.

Niedermeier M, Einwanger J, Hartl A, Kopp M. Affective responses in mountain hiking—a randomized crossover trial focusing on differences between indoor and outdoor activity. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(5):e0177719.

Niedermeier M, Hartl A, Kopp M. Prevalence of mental health problems and factors associated with psychological distress in mountain exercisers: a cross-sectional study in Austria. Front Psychol. 2017. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01237.

White MP, Elliott LR, Taylor T, Wheeler BW, Spencer A, Bone A, et al. Recreational physical activity in natural environments and implications for health: a population based cross-sectional study in England. Prev Med. 2016;91:383.

Thompson Coon J, Boddy K, Stein K, Whear R, Barton J, Depledge MH. Does participating in physical activity in outdoor natural environments have a greater effect on physical and mental wellbeing than physical activity indoors? A systematic review. Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45:1761.

Pasanen TP, Tyrväinen L, Korpela KM. The relationship between perceived health and physical activity indoors, outdoors in built environments, and outdoors in Nature. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2014;6(3):324.

Howarth M, Brettle A, Hardman M, Maden M. What is the evidence for the impact of gardens and gardening on health and well-being: a scoping review and evidence-based logic model to guide healthcare strategy decision making on the use of gardening approaches as a social prescription. BMJ Open. 2020;10(7):e03692.

Ryu J, Heo J. Relationships between leisure activity types and well-being in older adults. Leis Stud. 2018;37(3):331.

Pomfret G, Sand M, May C. Conceptualising the power of outdoor adventure activities for subjective well-being: a systematic literature review. J Outdoor Recreat Tour. 2023;42:100641.

Hobson JSP, Dietrich UC. Tourism, health and quality of life: Challenging the responsibility of using the traditional tenets of sun, sea, sand, and sex in tourism marketing. J Travel Tour Mark. 1995;3(4):21.

Gilbert D, Abdullah J. Holidaytaking and the sense of well-being. Ann Tour Res. 2004;31(1):103.

de Bloom J, Geurts SAE, Sonnentag S, Taris T, de Weerth C, Kompier MAJ. How does a vacation from work affect employee health and well-being? Psychol Health. 2011;26(12):1606.

Frances K. Outdoor recreation as an occupation to improve quality of life for people with enduring mental health problems. Br J Occup Ther. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802260606900406.

Salmon P. Effects of physical exercise on anxiety, depression, and sensitivity to stress: a unifying theory. Clin Psychol Rev. 2001;21(1):33.

Townsend M. Feel blue? Touch green! Participation in forest/woodland management as a treatment for depression. Urban For Urban Green. 2006;5(3):111.

Kim HS. Effect of pain, nutritional risk, loneliness, perceived health status on health-related quality of life in elderly women living alone. J Korea Converg Soc. 2017;8(7):207–18.

Lim LL, Kua EH. Living alone, loneliness, and psychological well-being of older persons in Singapore. Curr Gerontol Geriatr Res. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/673181.

Ingram Ashley. The mental benefits of club involvement—the bhs Beat. 2021. https://bhsbeat.org/3109/student-life/the-mental-benefits-of-club-involvement/. Accessed 11 Jan 2023.

McHugh Power JE, Steptoe A, Kee F, Lawlor BA. Loneliness and social engagement in older adults: a bivariate dual change score analysis. Psychol Aging. 2019;34(1):152.

Zali M, Farhadi A, Soleimanifar M, Allameh H, Janani L. Loneliness, fear of falling, and quality of life in community-dwelling older women who live alone and live with others. Educ Gerontol. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2017.1376450.

Bradshaw M, Ellison CG. Do genetic factors influence religious life? findings from a behavior genetic analysis of twin siblings. J Sci Study Relig. 2008;47(4):529.

Cohen AB, Johnson KA. The Relation between Religion and Well-Being. Appl Res Qual Life. 2017;12(3):533.

Ellison CG, Boardman JD, Williams DR, Jackson JS. Religious involvement, stress, and mental health: findings from the 1995 Detroit area study. Soc Forces. 2001;80(1):215.

Hank K, Schaan B. Cross-national variations in the correlation between frequency of prayer and health among older Europeans. Res Aging. 2008;30(1):36.

Krause N. Church-based social support and health in old age: exploring variations by race. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57(6):S332.

Sternthal MJ, Williams DR, Musick MA, Buck AC. Depression, anxiety, and religious life: a search for mediators. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(3):343.

Son J, Wilson J. Volunteer work and hedonic, eudemonic, and social well-being. Sociol Forum. 2012;27(3):658.

Lee S. The volunteer and charity work of European older adults: findings from SHARE. J Nonprofit Public Sector Market. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495142.2022.2130498.

Potočnik K, Sonnentag S. A longitudinal study of well-being in older workers and retirees: the role of engaging in different types of activities. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2013;86(4):497.

Zhang Y, Li F. The relationships between urban parks, residents’ physical activity, and mental health benefits: a case study from Beijing, China. J Environ Manag. 2017;190:223.

Lee ACK, Maheswaran R. The health benefits of urban green spaces: A review of the evidence. J Public Health. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdq068.

Gascon M, Mas MT, Martínez D, Dadvand P, Forns J, Plasència A, et al. Mental health benefits of long-term exposure to residential green and blue spaces: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120404354.

McCormack GR, Cabaj J, Orpana H, Lukic R, Blackstaffe A, Goopy S, et al. A scoping review on the relations between urban form and health: a focus on Canadian quantitative evidence. Health Promotion Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2019;39(5):187.

Larson LR, Jennings V, Cloutier SA. Public parks and wellbeing in urban areas of the United States. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(4):e0153211.

Lachowycz K, Jones AP. Greenspace and obesity: a systematic review of the evidence. Obes Rev. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00827.x.

Helliwell JF, Layard R, Sachs JD, De Neve JE. World Happiness Report. New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network; 2021.

Kowitt SD, Aiello AE, Callahan LF, Fisher EB, Gottfredson NC, Jordan JM, et al. Associations among neighborhood poverty, perceived neighborhood environment, and depressed mood are mediated by physical activity, perceived individual control, and loneliness. Health Place. 2020;62:102278.

Maas J, van Dillen SME, Verheij RA, Groenewegen PP. Social contacts as a possible mechanism behind the relation between green space and health. Health Place. 2009;15(2):586.

Heesch K, van Uffelen J, van Gellecum Y, Brown W. Dose response relationships between physical activity, walking and health-related quality of life in mid-age and older women. J Sci Med Sport. 2012;15:S23.

Heesch KC, Burton NW, Brown WJ. Concurrent and prospective associations between physical activity, walking and mental health in older women. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65(9):807.

Steptoe A, Butler N. Sports participation and emotional wellbeing in adolescents. Lancet. 1996;347(9018):1789.

Tsuji T, Kanamori S, Saito M, Watanabe R, Miyaguni Y, Kondo K. Specific types of sports and exercise group participation and socio-psychological health in older people. J Sports Sci. 2020;38(4):422.

Bruun DM, Krustrup P, Hornstrup T, Uth J, Brasso K, Rørth M, et al. “All boys and men can play football”: a qualitative investigation of recreational football in prostate cancer patients. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12193).

Darongkamas J, Scott H, Taylor E. Kick-starting men’s mental health: an evaluation of the effect of playing football on mental health service users’ well-being. Int J Mental Health Promot. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623730.2011.9715658.

Lozano-Sufrategui L, Pringle A, Carless D, McKenna J. ‘It brings the lads together’: a critical exploration of older men’s experiences of a weight management programme delivered through a healthy stadia project. Sport Soc. 2017;20(2):123–35.

Mynard L, Howie L, Collister L. Belonging to a community-based football team: an ethnographic study. Aust Occup Ther J. 2009;56(4):266–74.

Mason OJ, Holt R. A role for football in mental health: the coping through football project. Psychiatrist. 2012;36(8):290–3.

Ottesen L, Jeppesen RS, Krustrup BR. The development of social capital through football and running: studying an intervention program for inactive women. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20(Suppl):1.

Müller E, Gimpl M, Poetzelsberger B, Finkenzeller T, Scheiber P. Salzburg skiing for the elderly study: study design and intervention—health benefit of alpine skiing for elderly. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2011.01336.x.

Gilleard C, Higgs P. The third age: class, cohort or generation? Ageing Soc. 2002;22(3):369.

Bardhoshi G, Jordre BD, Schweinle WE, Shervey SW. Understanding exercise practices and depression, anxiety, and stress in senior games athletes: a mixed-methods exploration. Top Geriatr Rehabil. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1097/TGR.0000000000000092.

Östlund-Lagerström L, Blomberg K, Algilani S, Schoultz M, Kihlgren A, Brummer RJ, et al. Senior orienteering athletes as a model of healthy aging: a mixed-method approach. BMC Geriatr. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-015-0072-6.

Jacobson KJ. The American adrenaline narrative. Georgia: University of Georgia Press; 2020.

Khor PH, Asrar Zulkefl ZA, Lim KC. The Langkawi island market potential for extreme outdoor sports tourism/Khor Poy Hua, Zul Arif Asrar Zulkefli and Khong Chiu. Voice of Academia. 2022;18(2):17–30.

Rapi S, Kristo I, Tase I. Hedonism and adrenaline—emotional relation with rafting. Chin Bus Rev. 2018. https://doi.org/10.17265/1537-1506/2018.07.002.

Acknowledgements

Authors want to thank all the respondents for providing all the information and permit us for using the data for independent research.

Funding

No financial grants were achieved.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MMT had all access to the data and validation of the statistical analysis. Formal Analysis: MMT. Data Curation: MMT. Original Drafting: MMT, IJJ, AK, FA and MAR. Writing and Critical Review: MMT, MAR. Supervise and validation: MAR.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Authors of this study thank to Development Studies Discipline of Khulna University, Bangladesh for approving this study. This study is produced as the partial fulfillment of the first author’s Master’s thesis project and endorsed by his supervisor that we didn’t violate any ethical standard carrying out the research from data collection to study design, even, no clinical data have been collected and used for this study.

Informed consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Competing interests

All authors declare they do not have any potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tohan, M.M., Ahmed, F., Juie, I.J. et al. Outdoor recreational activities and mental well-being of geriatric people in Bangladesh: structural equation modelling. Discov Psychol 4, 33 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-024-00131-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-024-00131-8