Abstract

Despite the fact that children with disabilities generally have been shown to be at a greater risk of bullying, which include physical attacks and threats, being picked on and teased and verbal abuse, there is still a need to understand bullying of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and the strategies used by parents to support them in tackling this issue. This study aims to investigate the type and level of occurrence of bullying and parental support for children aged five with ASD who suffer from bullying. This study used both quantitative and qualitative analysis; a questionnaire, distributed to mothers of children with ASD, adopted from the Bullying for ASD Survey developed by Chen and Schwartz (Focus Autism Other Dev Disabil 27(4):200–212, 2012) measured types and frequency of bullying and parental support. An open-ended question was added to the survey to enable parents to write about the ways in which their child was bullied and the ways in which they supported their child. The results showed that while children suffered from all types of bullying, especially being picked on, being excluded and called names. Parental support showed a higher prevalence of involving peers and teachers for the prevention of bullying as well as avoiding strategies which included avoiding bullies and none of the mothers encouraged their children to stand up to bullies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The characteristics of individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) include communication and social difficulties, extreme sensitivity to most sensory stimuli, and repetitive behaviours [1]. In addition, they may have problems with non-verbal communication and taking turns in conversation. The estimated prevalence of ASD in the UK has been stated to be 1–3% of the population [2]. Children with ASD are at an increased risk of bullying at school [3, 4] and bullying is more likely to occur significantly earlier in children with ASD than in children without ASD [5]. In fact, a significant relationship between the severity of ASD and the risk of being bullied has been found [6]. Bullying is defined as behaviours carried out and repeated with the intention of causing emotional distress or physical harm [7]. Various factors contribute to bullying of children with ASD, for example, different levels of social understanding [8] and stereotypes and negative beliefs held by neurotypical children resulting in discrimination and prejudice [9]. Hsiao et al. [10] found that psychopathologies mediated the link between ASD and bullying in addition to the direct effect of ASD on bullying victimisation.

Research findings have indicated that bullying can have a variety of detrimental outcomes for the child victim with ASD, such as problems with mental health, suicidal thoughts, and damaged self-esteem [11,12,13]. It was found that in groups of children in inclusive schooling, 75% were bullied, of which 40% felt rejected as a result of their victimisation [14]. School refusal is another problem for children with ASD, Ochi et al. [5] found that school refusal occurred earlier in children with ASD than in those children without. Children in inclusive school settings have been found to be more likely to be bullied than children in special education schools [15,16,17].

The study makes a contribution to understanding the type of bullying and frequency of bullying experienced by children and how mothers cope, as current research is often centred around much older children and adolescents and the coping strategies of mothers has been little studied. Towards the development of strategies to support children there has been much work to understand bullying, which has included consideration of the experiences of parents. The objective of the study is to reveal how mothers support children at this age who are victims of bullying. This study considers that a beneficial contribution to such knowledge would be to reveal the approaches that parents use to support their children with ASD who are victims of bullying. The study reveals these approaches which can contribute to the development of future strategy for younger children with ASD.

2 Literature review

Hwang et al. [4] describe the issue of bullying of children with ASD as significant, highlighting their greater risk of bullying exposition compared to other children in the community. They propose that there is a need to effectively recognise children with ASD and the danger of school bullying and develop strategies and interventions to support them. Chou et al. [18] who examined the role of bullying involvement in depression and anxiety among adolescents, draw analogous conclusions when commenting on such issues among individuals with ASD who have experienced bullying, pointing out that this topic should be regularly examined.

Parental involvement in children with ASD who are victims of bullying has been addressed from a number of different perspectives. Mademtzi et al. [19] examined the parental experiences of caring for female children with ASD and found that parents said they suffered the same issues as males including difficulty in social interactions. The general experience of parents caring for children with ASD has included bullying as a challenged faced by parents [20]. Views from parents have also been sought to identify the types of bullying that their children. Kloosterman et al. [21] examine the parental agreement with children’s experience of bullying where it was found that there was a high level of agreement between parents and children with ASD than other children. This suggests that parents of children with ASD are more aware of the types bullying that their children are victims of. Ashburner et al. [22] examined the perception of parents of how bullying affected their children, parental concerns included the effects of bullying on self-esteem, attendance, social participation, mental health, behaviour and academic performance.

Much of literature about children with ASD and bullying focus on strategies of support generally including the prevention of bullying [23]. Researchers have contributed through identifying risk factors that are associated with vulnerability and protection [3]. Interventions from educational establishments and from parents’ recommendations are provided based on the findings where parents perceptions are sought. Where parents are consulted it is for their perspectives on bullying of their children with ASD [15]. VanOrmer et al. [24] found that parental tolerance of children’s behaviour with ASD was important in shaping the discipline strategy that parents used, their study found that parents of children with ASD were more tolerant of their child’s disruptive behaviour. Importantly, Kloosterman et al. [21] bring attention to the fact that parents are often involved in helping their children, however, this is limited to asking from parents the type and frequency of their child’s bullying. This supports the position of the present study that there is a need to understand more than just types of bullying that are experienced from the parents’ perspective, there is a need to understand further the strategies that parents use. Yoo et al. [25] examine the use of a parent-assisted social skills training program for teens with ASD which was shown to be effective in improving social skills of adolescents in North America. Schiltz et al. [26] examined the link between the challenging behaviour of youth with ASD and parental stress and involvement and found that stress has a negative impact on parental involvement, motivating the need to consider the whole family system in research on young people with ASD.

A far-reaching study by Carrington et al. [27] investigated the perspectives of students with ASD and their parents in terms of dealing with bullying in an Australian school and concluded with a range of recommendations and strategies, such as raising awareness of bullying; developing rules that can be more clearly linked to school, students, and their parents; improving communication and relationships within families to overcome bullying; and providing coping strategies to deal with bullying. This study was more comprehensive in that it included both children and parents to derive communication and coping strategies [27], however the children were between 11 and 16 years of age, the weakness being that the wide age cohort would include children and adolescents whereby experiences and coping strategies could differ.

Laugeson et al. [28] asked a sample of 33 teenagers with ASD to complete, with parental help, assignments designed to teach a range of social skills. The researchers found that the intervention increased the quality of the teenagers’ friendships and their social etiquette. Unfortunately, the researchers did not comment on the intervention’s effects on bullying. Additionally, the intervention did not teach the teenagers how to respond to bullying.

These studies are focussed on teenagers and students and such recommendations for interventions may not be appropriate for younger children. Therefore, there is a need to reveal how young children are supported. It is noticeable in the literature that studies about parents’ involvement or experiences are often related to older children and adolescents, high school pupils and adolescents [25, 26, 29] students [22, 27] older children between the ages of 9 and 14. There have been few studies that have considered much younger children, however, these studies also included adolescents and adults [19].

Furthermore, few studies have been conducted to understand the parental support of young children with ASD who are victims of bullying. Zeedyk et al. [30] commented on the dearth of research in this area, noting that strategies are required not only to support the social communication skills of children with ASD, but also to empower them to sustain healthy peer relationships and avoid being at risk of victimisation. Furthermore, while there has been research on parenting behaviour among parents who have children with ASD, the degree of involvement or engagement has not received much attention (Schiltz et al. 2018).

To the best of this researcher’s knowledge, no studies have reported on the topic of parental support solely in aiding children in the 5 years age cohort with ASD as a response to bullying. The present study thus aims to investigate how parents support their children with ASD, at age 5 in primary school, to respond to bullying. Parents are asked about frequency of bullying, types of bullying in addition to the support parents provide for their children to help them respond to bullying.

3 Method

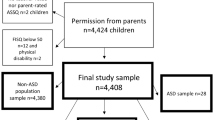

3.1 Participants

Seven mothers agreed to take part in the study. Their children were 5 years old, had been diagnosed with ASD (Mothers were asked if their child had been diagnosed with ASD, with the following question: ‘Has a doctor or health professional ever told you that [your child] has autism … or autistic spectrum disorder?’ ([31], p. 2310)) and were attending a reception class in an inclusive primary school. Three of the children were male and four were female. They were given pseudonyms as follows: Anne, Billie, Cathy, Daphne, Elizabeth, Thomas, and John.

3.2 Instruments

The aims of the study were to reveal the experiences of bullying from the perspective of mothers including type and frequency of bullying and how mothers support their child where their children are being bullied. For the type and frequency of bullying the Bullying for ASD Survey developed by Chen and Schwartz [32] was adopted in this study for the mothers to complete. The survey is suitable for measuring bullying for children with ASD from the parental perspective and has been previously validated by Chen and Schwartz [32]. This survey was informed by a number of different surveys including Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire by Olweus [33] and the Self-Report Victimisation Scale by Ladd and Kochenderfer-Ladd [34]. Importantly, the survey includes a parent version in addition to teacher and student version [32]. The parent version of the questionnaire asked questions related to the same constructs that children are asked. In the original survey there were ten types of bullying included the same items were included in the present study.

A four-point Likert scale of frequency was used in the questionnaire. For the first part of the questionnaire parents were asked about the type and frequency of bullying that their children experienced (Table 1). An open-ended question was added to the end of this section to allow the mothers to write about any other ways in which their child was being bullied at school. For the second part of the questionnaire mothers were questioned about the type and frequency of support that they gave children (Table 2). Mothers were also given the opportunity to write about other ways that they support their children.

3.3 Procedure

The researcher contacted an associate who had a 5-year-old child with ASD who had experienced bullying in primary school. Six additional mothers were identified by of word of mouth from the initial contact; this was snowball sampling where the participants were identified from the personal contacts and social network of the earlier participants [35]. All participants had a 5-year-old child with ASD, who had experienced bullying at school. A consent form was sent, signed, and returned (see Appendix A) via email, by each participant. The two survey questionnaires were emailed to the participants, completed, and emailed back to the researcher.

4 Results

4.1 Parents’ reports of types of bullying at school using the bullying for ASD Survey

Table 1 displays the different types of bullying at school, according to mothers’ responses to the Bullying for ASD Survey questionnaire. A total of five children had been picked on by their peers on more than five occasions. Four children had been excluded by their peers, also on more than five occasions. Five children had also had rumours spread about them at least five times. Seven had been called names; for four children this had happened three or four times, and for three children it had happened five or more times. One had been teased on five or more occasions. A total of five children had been kicked or hit, three once or twice and two on three or four occasions. Only two out of the seven children had had their property destroyed, on one or two occasions, whereas six children had been teased on three or four occasions, and one had been teased five or more times.

4.2 Parents’ reports of other types of bullying at school

In answer to the open-ended question included in the Bullying for ASD Survey, ‘Please could you state any other ways in which your child has been bullied with an example’, six mothers responded with the following examples of bullying experienced by their child:

Other children bully Thomas by frightening him. They say things like, ‘I don’t think your mum is going to pick you up today’. (Thomas’ mother)

During PE lessons they hide her coat, shoes, laces, socks. They have even hidden her lunchbox. (Elizabeth’s mother)

They tell lies about John. They say something like, ‘John swore at me’. John ends up being told off for something he hasn’t done. The head teacher said he has got to stand up for himself. (John’s mother)

They are always tricking her into a difficult situation. The bully, and there are usually two of them, said once, ‘Kalid has lost his chocolate bar, oh look, Cathy has got it in her bag’. (Cathy’s mother)

Other children want the best seat at the back of the class, and if Anne sits on that seat she is told to move from that seat. (Anne’s mother)

Billy often talks too much when others have had enough of the conversation. Then they tease him and call him stupid. (Billy’s mother)

4.3 Parents’ reports of the ways they support their child to respond to bullying, using the Parents’ Support Survey Questionnaire

The mothers in the sample agreed that they provided their children with ways to respond to bullying, displayed in Table 2. A total of four mothers agreed that they asked their child five or more times ‘not to carry any valuables with them to school’. Five asked their children three or four times ‘to walk with a friend when they walk to different rooms at school’. Four reported that they discussed once or twice and two had talked to their child on five or more occasions ‘about inappropriate and appropriate behaviour from other children at school’. Four mothers had discussed how their child could ‘get help by approaching teachers’.

4.4 Parents’ reports of other ways in which they support their child to respond to bullying

In answer to the open-ended question included in the Parents’ Support Survey questionnaire, ‘Please could you state the ways in which you support your child to respond to bullying when they are at school’, four mothers responded to the question. The idea of using teachers for support was suggested in terms of being near the teacher to avoid bullying.

I try to remain calm when I’m talking to Daphne about bullying. I have talked to her about approaching teachers, not to talk to them, just to stand near them. That seems to work for her. The bully keeps away from her. If I show that I am worried she picks up on that. (Daphne’s mother)

I have contacted the school several times to ask them to punish bullies. I can only tell John to go to the teacher when other children make him feel uncomfortable or are being abusive towards him, otherwise they still bully him. (John’s mother)

To get the child to concentrate on their schoolwork was another way of parental support for the child:

Anne doesn’t want to go to school sometimes. I’ve had to boost her self-confidence and remind her that she can concentrate on subjects because she has ASD, and she could do that better than children without ASD. If she was feeling low, I don’t think she would have been able to cope with the pressure of bullying. (Anne’s mother)

Avoidance was a strategy that was revealed in this study, that parents have suggested the child simply ignores confrontation to avoid bullying:

Billie switches off when he feels overwhelmed with others. He prefers to be on his own. I have suggested it is okay for him to do this because he avoids confrontation. (Billie’s mother)

5 Discussion

The study set out to investigate the type and frequency of bullying of children with ASD from the perspective of mothers and how mothers supported their children who are victims of bullying. This was achieved with a questionnaire where the quantitative element measured types and frequency of bullying and types of parental support and a qualitative open question section that allowed mothers to elaborate on how they support their children. In their responses to the bullying survey, all mothers reported that their children had been bullied on at least three or four occasions, and many had been bullied on five or more occasions. The children had experienced all ten types of bullying set out in the bullying survey. A large majority of the children had been picked on, had rumours spread about them, and had been excluded. The mothers reported additional types of bullying experienced by their child, including being frightened, having their possessions stolen, others telling lies about them, and being tricked into difficult situations.

All the mothers reported that they provided support in agreement with the six items on the support survey. They also reported additional ways that they supported their child to help them respond to bullying which included being calm about the situation, Daphne’s mother reported that her support involved being calm and that this was important when she was advising her daughter on how to respond to bullying behaviour. Parental stress can act as a moderator between anxiety and bullying victimisation. In a study of 101 mothers of young adults and teenagers with ASD, it was found that if parents were highly stressed, children with ASD experienced more anxiety related to bullying victimisation [36]. Daphne’s mother was able to support her daughter to respond to bullying by suggesting she position herself within close proximity to teachers for protection, this was to boost self-confidence.

Anne’s mother reported that her daughter did not always want to go to school. Research has noted that school avoidance is common among children with ASD when they are victims of bullying [5, 37]. Anne’s mother also reported that her daughter had low self-esteem because of the bullying; consequently, she provided support to increase Anne’s sense of self-esteem to help her feel good about going to school [38].

Billie’s mother reported that he switches off when he feels overwhelmed at school; when he does this, he avoids confrontation. It seems that Billie uses an avoidant strategy when he feels like he is not in control of a situation. Dated but relevant research has noted that this is common among children with ASD who encounter frequent bullying at school [39].

John’s mother was frustrated with the lack of punishment being given out to bullies and had appealed to her son’s school to punish bullies. This is a common parent request. Past research has reported that other parents of children with ASD have contacted their child’s school with this request [27]. The researchers recommended that school practices and policy should set out ways in which they can reduce the incidence of bullying in inclusive and special education.

None of the parents suggested to their child that they stand up to the bully. Rather, the parents’ support strategies were associated with avoidant strategies, particularly approaching a teacher, and telling them about the situation or being in close proximity to a teacher when moving about the school. These support strategies may be considered as suggestions of passive behaviours, which may not be effective against bullying. When children engage in particular strategies to cope with bullying, such as helpless behaviour, fighting back, or passive behaviours, that these strategies are the least effective in coping with bullying [40]. It may be that the mothers do not wish their children to get too involved with the bully, because of the possible repercussions. Zablotsky et al. [15] found that, out of a total of 1221 parents of children with ASD who completed their survey, found that only 18.5% reported that their children had an emotional outburst or were provoked and fought back.

Where this study has contributed to the current research is that it has investigated how mothers support their children with ASD when they are bullied. This approach takes ideas from parents rather than offering strategies to parents, or just simply investigating frequencies of bullying from parents. The contribution here is that strategies are taken from parents who are perhaps in a better position, through experience, to offer recommendations, something that has been missing in the research. Furthermore, there has been a lack of research for younger children alone, this study has provided insight into an age group where experience of bullying and parental support may be different than for older children and adolescents.

6 Conclusion and recommendations

This investigation aimed to assess how parents support their child with ASD, at age five, in primary school, to respond to bullying. Children with ASD are a vulnerable group at greater risk of bullying victimisation. Since parents have a responsibility to protect their children with ASD, continued efforts are needed via research to make practical recommendations by identifying coping strategies associated with bullying and parenthood. An important task for future research is to examine and recommend coping strategies for children with ASD. Specifically, the development of future intervention should consider the experienced positions and approaches of the parents dealing with bullying of children with ASD. In light of this it is recommended that there is further investigation into the effectiveness of these parental approaches.

The generalisability of these results is subject to certain limitations. For instance, observation of real-life bullying in a school context or children’s responses to bullying in that setting was not the focus of this research, since the researcher wanted to avoid causing distress or harm to the children who were discussed in this study. Thus, the research data derived solely from mothers’ responses to the survey questionnaire and their comments in response to the two open-ended questions provided at the end of the survey questionnaires. The research was carried out with questionnaires sent and returned by email, to adhere to the requirements of the government’s rules on social distancing and staying at home during the Covid-19 pandemic. More detailed data might have been obtained if the researcher had been able to interview the mothers in person. Additionally, the mothers’ reports of their child’s experience of bullying and the support they provided, could not be further verified by the researcher. Due to practical considerations the research sample was relatively small, a future study should include a larger sample.

Finally, it was a contribution of the study that a specific age was considered, a future study could investigate if there are differences in experiences and support by parents between different age groups. This would contribute to more age-appropriate strategies to support these children.

References

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

Dillenburger K, Jordan JA, McKerr L, Keenan M. The Millennium child with autism: early childhood trajectories for health, education and economic wellbeing. Dev Neurorehabil. 2015;18(1):37–46.

Forrest DL, Kroeger RA, Stroope S. Autism spectrum disorder symptoms and bullying victimization among children with autism in the United States. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020;50(2):560–71.

Hwang S, Kim YS, Koh YJ, Leventhal BL. Autism spectrum disorder and school bullying: who is the victim? Who is the perpetrator? J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(1):225–38.

Ochi M, Kawabe K, Ochi S, Miyama T, Horiuchi F, Ueno SI. School refusal and bullying in children with autism spectrum disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2020;14(1):1–7.

Eroglu, Kilic BG. Peer bullying among children with autism spectrum disorder in formal education settings: data from Turkey. Res Autism Spectrum Disord. 2020;75:101572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2020.101572.

Aitken K. Evidence-based assessment in ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder): what is available, what is appropriate and what is ‘fit-for-purpose’. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2017.

Garner PW, Hinton TS. Emotional display rules and emotion self-regulation: associations with bullying and victimization in community-based after school programs. J Community Appl Soc Psychol. 2010;20(6):480–96.

Humphrey N, Symes W. Peer interaction patterns among adolescents with autistic spectrum disorders (ASDs) in mainstream school settings. Autism. 2011;15(4):397–419.

Hsiao R, Tai Y-M, Wu Y-Y, Tsai W-C, Chiu Y-N, Gau SS-F. Psychopathologies mediate the link between autism spectrum disorder and bullying involvement: a follow-up study. J Formosan Med Assoc. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfma.2021.12.030.

Hebron J, Humphrey N. Mental health difficulties among young people on the autistic spectrum in mainstream secondary schools: a comparative study. J Res Spec Educ Needs. 2014;14(1):22–32.

Mayes SD, Gorman AA, Hillwig-Garcia J, Syed E. Suicide ideation and attempts in children with autism. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2013;7(1):109–19.

Rybcznski S, Lipkin PH, Vasa RA. Suicide screening in neurodeveopmental and autism clinics: early data and implications. In: Peer-reviewed conference presentation at the 2018 International Meeting for Autism Research (INSAR), Rotterdam, The Netherlands. 2018.

Rowley E, Chandler S, Baird G, Simonoff E, Pickles A, Loucas T, Charman T. The experience of friendship, victimization and bullying in children with an autism spectrum disorder: associations with child characteristics and school placement. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2012;6(3):1126–34.

Zablotsky B, Bradshaw CP, Anderson CM, Law P. Risk factors for bullying among children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism. 2014;18(4):419–27.

McClemont AJ, Morton HE, Gillis JM, Romanczyk RG. Brief report: Predictors of school refusal due to bullying in children with autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2021;51(5):1781–8.

Ofe EE, Plumb AM, Plexico LW, Haak NJ. School-based speech-language pathologists’ knowledge and perceptions of autism spectrum disorder and bullying. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch. 2016;47(1):59–76.

Chou WJ, Wang PW, Hsiao RC, Hu HF, Yen CF. Role of school bullying involvement in depression, anxiety, suicidality, and low self-esteem among adolescents with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:9.

Mademtzi M, Singh P, Shic F, Koenig K. Challenges of females with autism: a parental perspective. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;48(4):1301–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3341-8.

Glazzard J, Overall K. Living with autistic spectrum disorder: parental experiences of raising a child with autistic spectrum disorder (ASD). Support Learn. 2012;27:37–45.

Kloosterman PH, et al. Types and experiences of bullying in adolescents with an autism spectrum disorder. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2013;7(7):824–32.

Ashburner J, Saggers B, Campbell M, Dillon-Wallace J, Hwang Y, Carrington S, Bobir N. How are students on the autism spectrum affected by bullying? Perspectives of students and parents. J Res Spec Educ Needs. 2018;19(1):27–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12421.

Winchell BN, Sreckovic MA, Schultz TR. Preventing bullying and promoting friendship for students with ASD. Educ Train Autism Dev Disabil. 2018;53(3):243–52.

VanOrmer JL, Edwards GS, Zlomke KR, Proctor KB, Brestan-Knight E. Examination of parental tolerance among parents of young children with and without ASD. Adv Neurodev Disord. 2018;2(2):169–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41252-018-0054-8.

Yoo H-J, Bahn G, Cho I-H, Kim E-K, Kim J-H, Min J-W, Lee W-H, Seo J-S, Jun S-S, Bong G, Cho S, Shin M-S, Kim B-N, Kim J-W, Park S, Laugeson EA. The Korean version of the PEERS® for ASD. Autism Res. 2014;7:145–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1354.

Schiltz HK, McVey AJ, Magnus B, et al. Examining the links between challenging behaviors in youth with ASD and parental stress, mental health, and involvement: applying an adaptation of the family stress model to families of youth with ASD. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(4):1169–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3446-0.

Carrington S, Campbell M, Saggers B, Ashburner J, Vicig F, Dillon-Wallace J, Hwang YS. Recommendations of school students with autism spectrum disorder and their parents in regard to bullying and cyberbullying prevention and intervention. Int J Incl Educ. 2017;21(10):1045–64.

Laugeson EA, Frankel F, Mogil C, Dillon AR. Parent-assisted social skills training to improve friendships in teens with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39(4):596–606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-008-0664-5.

N Lordo D, Bertolin M, L Sudikoff E, et al. Parents perceive improvements in socio-emotional functioning in adolescents with ASD following social skills treatment. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47(1):203–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2969-0.

Zeedyk SM, Rodriguez G, Tipton LA, Baker BL, Blacher J. Bullying of youth with autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, or typical development: victim and parent perspectives. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2014;8(9):1173–83.

Toseeb U, McChesney G, Wolke D. The prevalence and psychopathological correlates of sibling bullying in children with and without autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(7):2308–18.

Chen PY, Schwartz IS. Bullying and victimization experiences of students with autism spectrum disorders in elementary schools. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabil. 2012;27(4):200–12.

Olweus Dan. Bully/victim problems in school. Prospects. 1996;26(2):331–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02195509.

Ladd GW, Kochenderfer-Ladd B. Identifying victims of peer aggression from early to middle childhood: analysis of cross-informant data for concordance, estimation of relational adjustment, prevalence of victimization, and characteristics of identified victims. Psychol Assess. 2002;14(1):74–96. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.14.1.74.

Cohen L, Manion L, Morrison K. Research methods in education. London: Routledge; 2017.

Weiss JA, Cappadocia MC, Tint A, Pepler D. Bullying victimization, parenting stress, and anxiety among adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2015;8(6):727–37.

Swearer SM, Espelage DL, Vaillancourt T, Hymel S. What can be done about school bullying? Linking research to educational practice. Educ Res. 2010;39(1):38–47.

Hansen TB, Steenberg LM, Palic S, Elklit A. A review of psychological factors related to bullying victimization in schools. Aggress Violent Beh. 2012;17(4):383–7.

Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;56(2):267.

Kanetsuna T, Smith PK, Morita Y. Coping with bullying at school: children’s recommended strategies and attitudes to school-based interventions in England and Japan. Aggress Behav. 2006;32(6):570–80.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BHS and NHB wrote the main manuscript text and prepared figures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

That Internal Review Board (IRB) approval for the use of human subjects was granted prior to conduct of the research and guidelines were adhered to throughout the research process.

Competing interests

We do not have any interests that might be interpreted as influencing the research. Additionally, this manuscript has not been submitted to any other journal, nor is it under consideration for publication with any other entity.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A: Parents’ Consent Form

1.1 Project Title: Mothers’ responses to bullying of their 5-year-old children with autism spectrum disorder attending a reception class in an inclusive primary school

Dear participant,

This questionnaire is investigating ways in which parents support their child with ASD to respond to bullying.

This research is being carried out by [ ] under the supervision of [ ].

You will not be asked to provide your name, but you may be asked to provide some demographic information for analysis purposes. Data collected through this questionnaire will be aggregated and you will not be individually identifiable in any reports or publications from this research. All information collected will be kept securely and will only be accessible by [ ].

For more information about your rights as a participant in this research please download a copy of the participant information sheet which can be found at this link [ ].

We would be very grateful for your participation in this study. If you need to contact us in future, please contact me ( ) or [ ] ( ).

You can also contact us in writing at:.

Yours,

[ ]

1.2 Statement of Consent

By submitting a completed version of this questionnaire, you are consenting to the following:

-

I agree to participate in the research project, ‘Parental support for young children (aged 5) with autism spectrum disorder, to respond to bullying’ being carried out by [ ]

-

This agreement has been given voluntarily and without coercion.

-

I have been given full information about the study and contact details of the researcher(s).

-

I have read and understood the information provided above.

-

I have had the opportunity to ask questions about the research and my participation in it.

Appendix B: Parents’ bullying survey for ASD

‘Has a doctor or health professional ever told you that [your child] had Autism … or autistic spectrum disorder? | Yes | No | ||

My child has experienced the following: | Never | Once or twice | Three or four times | Five or more times |

Peers have picked on them | ||||

Peers have excluded them from activities | ||||

Peers have laughed at them | ||||

Peers have kicked or hit them | ||||

Peers have threatened them with physical harm | ||||

Being made fun of or teased by peers | ||||

Peers have made fun of them | ||||

Peers have made negative comments about them | ||||

Peers have destroyed their personal | ||||

Peers have called them names | ||||

Peers have spread rumours about them | ||||

Peers have picked on them | ||||

Please could you state any other ways in which your child has been bullied (and an example) | ||||

Appendix C: Parents’ Support Survey Questionnaire

I speak to my child about the following: | Never | Once or twice | Three or four times | Five or more times |

Talk with your child about inappropriate and appropriate behaviour from other children at school | ||||

Ask your child to stay close to teachers during play times | ||||

Ask child not to carry any valuables with them to school | ||||

Ask your child to walk with a friend or a teacher when they walk to different rooms at school | ||||

Discuss with your child their concerns about being with their peers at school | ||||

Discuss how your child can get help by approaching teachers | ||||

Please could you state the ways in which you support your child to respond to bullying when they are at school | ||||

Thank you for your participation in this study.

You are reminded that by submitting a completed version of this questionnaire you are agreeing to participate in this research.

If you have any queries, please contact me ( ) or [ ].

( ).

You can also contact us in writing at:

Yours,

[ ].

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Saigh, B.H., Bagadood, N.H. Bullying experiences and mothers’ responses to bullying of children with autism spectrum disorder. Discov Psychol 2, 33 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-022-00045-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-022-00045-3