Abstract

Background

Perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT) in obesity critically contributes to vascular dysfunction, which might be restored by long-term exercise. Protein kinase B/nitric oxide synthase/nitric oxide (Akt/eNOS/NO) down-regulation within PVAT might be involved in the impaired anti-contractile function of arteries. Therefore, the present study evaluated the effect of long-term aerobic exercise on PVAT function and the potential regulator during this process.

Methods

Male Sprague Dawley rats were divided into normal diet control group (NC), normal diet exercise group (NE), high-fat diet control group (HC), and high-fat diet exercise group (HE) (n = 12 in each group). Upon the establishment of obesity (20 weeks of high-fat diet), exercise program was performed on a treadmill for 17 weeks. After the intervention, circulating biomarkers and PVAT morphology were evaluated. Vascular contraction and relaxation were determined with or without PVAT. Production of NO and the phosphorylations of Akt (Ser473) and eNOS (Ser1177) within PVAT were quantified.

Results

Metabolic abnormalities, systemic inflammation, and circulating adipokines in obesity were significantly restored by long-term aerobic exercise (P < 0.05). The anti-contractile effect of PVAT was significantly enhanced by exercise in obese rats (P < 0.05), which was accompanied by a significant reduction in the PVAT mass and lipid droplet area (P < 0.05). Furthermore, the production of NO was significantly increased, and phosphorylation levels of Akt (Ser473) and eNOS (Ser1177) were also significantly promoted in PVAT by long-term aerobic exercise (P < 0.05).

Conclusion

Long-term aerobic exercise training restored PVAT morphology and anti-contractile function in obese rats, and enhanced the activation of the Akt/eNOS/NO signaling pathway in PVAT.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Both overweight and obesity were associated with increased all-cause mortality [1], estimated 70% of which were attributed to cardiovascular disease (CVD) [2]. Central obesity, typically represented by the excessive accumulation of visceral adipose tissue (VAT), has been reported as a critical risk factor for CVD [3]. Perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT), categorized as VAT, surrounds most blood vessels and regulates vascular homeostasis by releasing a variety of bioactive substances [4]. Nitric oxide (NO) is considered the primary mediator of vascular relaxing factors and was recently recognized as a key PVAT-derived gaseous bio-substance. However, in obesity, there are structural and functional changes in PVAT, which can contribute to a reduction in the production and/or bioavailability of NO, leading to vascular dysfunction [5, 6]. In the vasculature, NO production is mainly synthesized by nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) [7], and eNOS has been recognized to be expressed not only in the endothelium but also in the PVAT [8]. With a note, eNOS within PVAT may be even more important than endothelium eNOS in obesity-induced vascular dysfunction [9].

Long-term aerobic exercise has been proven to be beneficial in the prevention and treatment of CVD [10], during which PVAT is modulated [11]. Under pathological conditions of obesity, the exercise would restore PVAT function from sympathetic hyper-activation [12], pro-inflammation [13], and oxidative stress [14]. Previously, we have also shown that the phenotype of PVAT in obesity modified by exercise has an endothelium-independent influence on vascular reactivity [15]. In studies of obese rodents, exercise training, which lasted for at least 6 weeks, restored vascular function through activating eNOS (phosphorylation of serine 1177) in PVAT to increase NO production [16, 17]. However, the upstream molecules in PVAT responsible for the regulation of the eNOS/NO pathway are currently unclear, especially after long-term aerobic exercise intervention. Protein kinase B (Akt), a serine/threonine-specific protein kinase, could regulate eNOS activity via several signaling pathways [8, 18]. Since the protective roles of Akt during exercise on cardiovascular pathologies including ameliorating myocardial injury [19] and endothelial dysfunction [20] have been reported, Akt could be a potential upstream signal of eNOS within PVAT in obesity, which remains to be explored in the setting of exercise intervention.

In this study, we hypothesized that the anti-contraction function of PVAT would be restored after long-term aerobic exercise and that the activation of Akt/eNOS/NO was strongly involved in this process. These findings may provide a potential molecular target regarding the underlying mechanism of exercise therapy for cardiovascular diseases.

2 Results

2.1 Effects of Long-Term Aerobic Exercise on Body Weight and Circulating Biomarkers in Obese Rats

Sprague Dawley rats were divided into normal diet control group (NC), normal diet exercise group (NE), high-fat diet control group (HC), and high-fat diet exercise group (HE). Obesity was established in rats by high-fat feeding for 20 weeks and then underwent aerobic exercise training for 17 weeks. At the end of the intervention, the HC had significantly higher body weight than NC (P < 0.001), and HE had significantly lower body weight than the HC (P < 0.001). Significant differences in circulating lipid profiles were observed between groups: total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) in HC were significantly higher than that in NC (P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P < 0.001), and exercise significantly decreased those levels (HC vs. HE, P = 0.006, P = 0.017, P = 0.015); high-density lipoprotein (HDL) level in HC was down-regulated than NC, which was up-regulated by exercise (HC vs. HE, P < 0.001). In terms of glucose metabolism, the blood glucose (BG), insulin (Ins), and insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) levels of HC were significantly increased than NC (P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P < 0.001), and significantly restored in HE (P = 0.001, P = 0.018, P < 0.001). Similar results were observed on inflammatory factors (interleukin-6, IL-6; tumor necrosis factor-α, TNF-α; hypersensitive C-reactive protein, HS-CRP) and adipokines (leptin and resistin): levels were significantly higher in HC than NC (P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P = 0.003, P < 0.001, P < 0.001), and significantly down-regulated in HE than HC (P = 0.012, P = 0.001, P = 0.001, P = 0.036, P = 0.006). Circulating adiponectin, another adipokine, was observed significantly up-regulated by exercise (NC vs. NE, P = 0.010; HC vs. HE, P = 0.033). Data were summarized in Table 1.

2.2 Effects of Long-Term Aerobic Exercise on Mass and Morphology of PVAT in Obese Rats

To investigate the effects of long-term aerobic exercise on the mass and morphology of PVAT in obese rats, PVAT was weighed the mass and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) in each group of rats. High-fat diet resulted in a significant increase in PVAT mass (NC vs. HC P < 0.001; NE vs. HE P < 0.001), while long-term aerobic exercise training significantly decreased PVAT mass (HC vs. HE, P < 0.001) (Fig. 1a–b). H&E staining imaging demonstrated morphological differences between groups: compared with NC, the lipid droplets area of PVAT in HC was significantly higher (P < 0.001); compared with HC, this area in HE was significantly lower (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1c–d). No difference was observed among all groups regarding the thickness of the aorta (Fig. 1e).

Effects of long-term aerobic exercise on PVAT mass and morphology. a Representative images of the aorta with PVAT. b Summarized data of PVAT mass (n = 9). c Representative images of PVAT stained with H&E. d Quantification of lipid droplet area in PVAT (n = 4). e Quantification of aorta thickness (n = 4). The results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Differences between groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by LSD; * indicates P < 0.05. PVAT perivascular adipose tissue, H&E hematoxylin & eosin staining, NC normal diet control group, NE normal diet exercise group, HC high-fat diet control group, HE high-fat diet exercise group

2.3 Effects of Long-Term Aerobic Exercise on the Regulation of Aortic Function by PVAT in Obese Rats

To examine the effects of long-term aerobic exercise on PVAT function, we evaluated the concentration–response curves to phenylephrine (PE) and sodium nitroprusside (SNP). Concentration–response curves to PE were recorded in the endothelium-removed aorta with or without PVAT (Fig. 2a–d). For aorta without PVAT, the potency value for PE (pEC50) was significantly higher in HC than NC and HE (P = 0.021, P = 0.007), but the difference in pEC50 of aorta with PVAT was not observed among groups (Fig. 2e). The maximum contraction (Emax) value in aorta with PVAT was significantly reduced than aorta without PVAT, which were observed in NC, NE, and HE (P = 0.019, P = 0.023, P = 0.041) (Fig. 2f).

Effects of long-term aerobic exercise on vascular contraction with or without PVAT. a-d Concentration–response curves to PE in NC, NE, HC, and HE for aortic with or without PVAT. e Summarized pEC50 values obtained from concentration–response curves to PE. f Summarized Emax values of PE induced contraction. The results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3–6). Differences between groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by LSD; a paired t-test was used to compare the vascular contractions with and without PVAT from the same intervention group; * indicates P < 0.05. PVAT perivascular adipose tissue, PVAT + aortic rings with PVAT, PVAT- aortic rings without PVAT, PE phenylephrine, Emax maximum contraction, expressed as a percentage of KCl-induced maximum contractibility, pEC50 potency values, the negative logarithm of the 50% maximal effective concentration of PE, NC normal diet control group, NE normal diet exercise group, HC high-fat diet control group, HE high-fat diet exercise group

Concentration–response curves to SNP were also recorded in the endothelium-removed aorta with or without PVAT (Fig. 3a-d). For aorta with PVAT compared to that without PVAT, the concentration–response curves were all shifted to the right (Fig. 3e), and the potency value for SNP (pIC50) was significantly lower in HE (P = 0.007). No statistical difference was observed in maximum relaxation (Rmax) of the aorta with or without PVAT among or between any groups (Fig. 3f).

Effects of long-term aerobic exercise on vascular relaxation with or without PVAT. a-d Concentration–response curves to SNP in NC, NE, HC, and HE for aortic with or without PVAT. e Summarized pIC50 values obtained from concentration–response curves to SNP. f Summarized Rmax values of SNP induced relaxation. The results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3–6). Differences between groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by LSD; a paired t-test was used to compare the vascular contractions with and without PVAT from the same intervention group; * indicates P < 0.05. PVAT perivascular adipose tissue, PVAT + aortic rings with PVAT, PVAT-aortic rings without PVAT, SNP sodium nitroprusside, PE phenylephrine, Rmax maximum relaxation, expressed as a percentage of PE maximum contractibility, pIC50 the negative logarithm of the 50% maximal effective concentration of SNP, NC normal diet control group, NE normal diet exercise group, HC high-fat diet control group, HE high-fat diet exercise group

2.4 Effects of Long-Term Aerobic Exercise on NO Production in PVAT of Obese Rats

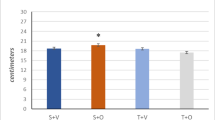

To explore the effect of long-term aerobic exercise on NO production in PVAT of obese rats, we examined NO production in the PVAT using fluorescent probe and Griess reagent. Aorta sections stained with the fluorescent NO probe showed that high-fat diet significantly reduced NO production in the PVAT (NC vs. HC, P < 0.001; NE vs. HE, P < 0.001), and long-term aerobic exercise significantly increased NO production in the PVAT (HC vs. HE P = 0.043) (Fig. 4a–b). The level of nitrite within PVAT in HC was also significantly lower than NC (P = 0.023) and HE (P = 0.039), suggesting a similar result of fluorescent NO staining (Fig. 4c).

Effects of long-term aerobic exercise on NO production in PVAT. a Representative fluorographs of DAF-2-treated sections of the thoracic aorta PVAT. Digital images were captured using 40 × , 100 × , and 200 × objectives. Green: NO; blue: nucleus counterstained by DAPI. b Quantitative analysis of the NO production measured by DAF-2-relative to DAPI in the aorta with PVAT (n = 3–4). c Nitrate levels in PVAT were measured using the Griess method (n = 5). The results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Differences between groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by LSD; * indicates P < 0.05. PVAT perivascular adipose tissue, DAPI destination access point identifier, DAF-2 4,5-diaminofluorescein diacetate, NO nitric oxide, NC normal diet control group, NE normal diet exercise group, HC high-fat diet control group; HE, high-fat diet exercise group

2.5 Effects of Long-Term Aerobic Exercise on Akt/eNOS Expression in PVAT of Obese Rats

To determine whether long-term aerobic exercise activated Akt/eNOS in the PVAT of obese rats, we examined Akt/eNOS protein expression in the PVAT by western blot. The Akt protein expression was not significant in PVAT between groups (Fig. 5a). The phosphorylation level of Akt (Ser473) in PVAT was significantly down-regulated in HC than NC (P = 0.047), and significantly up-regulated in HE compared with HC (P = 0.029) (Fig. 5b). There was no significant difference in the expressions of eNOS between groups (Fig. 5c). The phosphorylation level of eNOS (Ser1177) in PVAT from HC was significantly down-regulated than NC (P = 0.012), and significantly up-regulated in HE than HC (P = 0.003) (Fig. 5d).

Effects of long-term aerobic exercise on Akt/eNOS expression in PVAT. Representative western blot images and quantitative analysis of Akt expression (a) and its phosphorylation level at Ser437 (b), and eNOS expression (c) and its phosphorylation level at Ser1177 (d). The results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 4). Differences between groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by LSD; * indicates P < 0.05. Akt protein kinase B, pAkt Ser437 phosphorylation of Akt (Ser437), eNOS nitric oxide synthase, peNOS Ser1177 phosphorylation of eNOS (Ser1177), NC normal diet control group, NE normal diet exercise group, HC high-fat diet control group, HE high-fat diet exercise group

3 Discussion

As part of the vasculature, PVAT plays a key role on regulating cardiovascular function in obesity after exercise. The main findings of this study were that long-term aerobic exercise training restored PVAT morphology and anti-contractile function in obese rats. Meanwhile, the activation of the Akt/eNOS/NO signaling pathway within PVAT was enhanced through the long-term aerobic exercise.

It is well known that long-term aerobic exercise can improve vascular function in obesity [21] and that vascular adaptation to exercise critically contributes to this process, which is generally thought to result from structural changes, functional changes, or a combination of the two [22]. Based on our observation, no significant difference in vessel thickness was noted between groups. As for functional changes, our results showed that long-term aerobic exercise diminished high vascular sensitivity to PE in obese rats when PVAT was stripped, whereas no difference was observed between groups with intact PVAT. In addition, the PVAT reduces the drug sensitivity of the aorta to SNP. Those results highlighted a buffering capacity against vasoconstrictors and vasodilator of PVAT, and this buffering capacity to drugs is necessary to maintain the normal physiological function of vessels [23]. On the other hand, we found that in all groups except the HC group, the maximal contraction of PE was lower in the aorta with PVAT than that without PVAT, suggesting that the anti-contractile function of aortic PVAT in obesity was restored by this long-term exercise training (17 weeks) independently of the endothelium. A similar influence was recently observed in the mesenteric arteries of obese mice after 5 weeks swimming training [12] and also of obese rats after 8 weeks treadmill training [15]. However, after 8 weeks treadmill exercise, the anti-contractile function of thoracic aorta PVAT of obese rats was reduced [13] and even not altered in the femoral artery [14] and thoracic aorta [17] of obese mice. These contradictory reports might be explained by vessel types (mesenteric artery) and relatively short-term interventions (diet and exercise programs). We presume that relatively short-term exercise (less than 8 weeks) could be sufficient to provide a recovery effect on the anti-contractile function of PVAT surrounding arterioles while long-period training trial may be required in offsetting the chronic dysfunction of PVAT around aorta induced by long-term high-fat diet. Notably, evidence from persistent obese patients indicate that PVAT anti-contractile function was recovered due to reductions in local adipose inflammation and oxidative stress, represented by a decrease in adipocyte size through tissue biopsy [24]. Indeed, we also observed that long-term aerobic exercise training reduced the PVAT mass and the lipid droplet area in obese rats, accompanied by reliefs of systemic hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance, inflammation, and adipokine disorder. This suggests that long-term aerobic exercise training can improve the PVAT morphology, systemic inflammation, and metabolic level.

NO production within PVAT is an important mechanism for regulating local inflammation and oxidative stress, and we observed that NO bioavailability of PVAT in obese rats seemed to be reversed after long-term aerobic exercise training. Even though exercise-induced shear stress of blood flow was thought to mainly contribute to improving eNOS activity and thus to increased production of NO in vessel endothelium and medium [25], exercise training is sufficient to enhance eNOS expression in PVAT but not in aorta under healthy condition [26]. In the setting of obesity, both increase [16] and no obvious [17] change of eNOS within PVAT after exercise were observed, indicating the necessity of more emphasis on the regulatory factors of eNOS activity during this process. The activity of eNOS in the vasculature is modulated by phosphorylation at multiple sites [27], and eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1177 in PVAT is promoted by exercise in obese animals [16, 17], which is consistently observed in the current study. A recent study found that a reduction in phosphorylation of eNOS at Ser1177 in PVAT of obese mice was due to Akt inhibition [8], and Akt phosphorylation site at Ser437 appears to be essential for the regulation of eNOS activity by exercise training in the aorta [28, 29] and myocardium [30], therefore we additionally examined the potential role of Akt in PVAT. The results showed that the diminished phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 in obesity was enhanced by long-term aerobic exercise, which was in accordance with the activation of eNOS. Our findings showed that long-term aerobic exercise activated the Akt/eNOS/NO signaling pathway in PVAT in obese rats.

4 Limitation

Our study has limitations. Firstly, although we provide evidence that NO plays an important role in the exercise amelioration of obesity-induced PVAT dysfunction, the contribution of other PVAT-derived factors cannot be ruled out. Secondly, this study was conducted on male rats, and the effects of exercise on obese PVAT function on females could not be inferred considering the sex differences [31]. Thirdly, the two diets we used came from different suppliers: even though the calorie composition of the current standard diet (protein 21%, fat 12%, and carbohydrates 67%) is acceptable as previously discussed [32], the potential influence of other diet components on the study results cannot be excluded.

5 Conclusion

In summary, the results of the present study clearly indicated that long-term aerobic exercise training restored the anti-contractile function of PVAT. NO biosynthesis and activation of the Akt/eNOS signaling pathway within PVAT were strongly enhanced after long-term aerobic exercise intervention. Our study has the potential relevance for the clinical management of obese patients with vascular disorders.

6 Materials and Methods

6.1 Animals Intervention Protocols and Tissue Collection

Male Sprague Dawley rats (n = 48; 7 weeks old; weight, 120–140 g) were supplied by the Guangdong Medical Laboratory Animal Center (#44007200069346, Guangzhou, China). All animals were housed in a room with a constant temperature (22 ± 1 °C) and humidity of 50–60%, allowed access to diet and water ad libitum and exposed to a 12 h light–dark cycle. Rats were randomly assigned to high-fat diet group (H) (D12492, 60% kcal from fat, Research Diets, USA) and normal diet group (N) (standard diet, 12% kcal from fat, Guangdong Medical Laboratory Animal Center, China) for 20 weeks. The body weight of rats from H increased by ≥ 20% compared with the average body weight of that from N was considered obesity and used for further exercise intervention. Rats from H and N were then randomly divided into exercise group (E) and sedentary control group (C) respectively: NC, NE, HC, and HE (n = 12 in each group). The exercise program consisted of sessions of 60 min/day, 5 days/week, at a 0% grade and 55–65% of the maximal speed, for 17 weeks. The exercise intensity was established using an acute incremental exercise test as previously described [13]. During the period of treadmill training, the animals of each group were fed the same as their diet program. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangzhou Sport University (2021DWLL-13, Guangzhou, China) and adhered to the general ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

At 24 h after the last bout of training, rats were anesthetized (4% isoflurane, Reward, China) and then collected blood from the abdominal aorta. After animals were euthanized, the thoracic aorta was carefully isolated and placed in freshly prepared 4 °C Krebs solution (118 mM NaCl, 25.2 mM NaHCO3, 11.1 mM Glucose, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4 7.4 ddH2O, and 2.5 mM CaCl2 2H2O) and the PVAT was collected and stored at – 80 °C.

6.2 Serum Biomarkers Assay

The blood samples were centrifuged (3500 g for 15 min) to separate the TC, TG, HDL, LDL, and BG levels were measured in serum samples to the manufacturer’s instructions using a biochemical analyzer (Chemray 420, Rayto, China). Serum levels of Resistin (RX302767R, RuiXin Biotech, China), Ins, IL-6, HS-CRP, TNF-α, adiponectin, leptin were determined using a commercially available ELISA kit (MM-70260R1, MM-0190R1, MM-0081R1, MM-0180R1, MM-0553R1, MM-0596R1, MM-0211R1, Meimian, China). The HOMA-IR was calculated with the formula: Ins (uU/ml) × BG/22.5.

6.3 Histochemical Staining Characterization

The thoracic aorta with PVAT was carefully removed and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (P0099, Beyotime, China). Tissues were then washed and embedded in paraffin. Slides of tissue cross sections were stained with H&E for general histological observation. Images were obtained using a microscope (IX71-F22PH, Olympus, Japan). Quantification of lipid droplet area was determined using ImageJ software (NIH, USA); 4 randomly selected sections of droplet images for each rat were measured.

6.4 Wire Myography

Thoracic aortas (endothelium-denuded) were isolated and dissected into rings of 2 mm in length, with PVAT and connective tissues either removed (PVAT-) or left intact (PVAT +). Each ring was mounted in a myograph chamber (610 M; Danish Myo Technology, Denmark) with 5 mL of Krebs solution and equilibrated for 60 min under a resting tension of 10 mN. Then one dose of potassium chloride (KCl, 60 mM) was added to determine maximal contraction. Next, we assessed vascular response to PE (1 nM to 10 μM) and SNP (1 nM to 100 μM, after pre-contraction with 1 μM PE). Data acquisition was performed using LabChart 8.0 (AD Instruments, Australia). All concentration–response data were evaluated, and the responses for each agonist are shown as the maximum contraction/relaxation (Emax/Rmax) and potency (pEC50/pIC50) values.

6.5 Fluorescent Probe

The thoracic aorta surrounded by PVAT was embedded in the medium for frozen tissue specimens to optimal cutting temperature (Tisse TEK, Leica, Germany) and stored at – 80 °C. Fresh-frozen specimens were cross-sectioned at 7 μm thickness and placed on slides covered with poly-L-lysine solution (Citotest, China). The tissue was loaded with the sensitive fluorescent dye 4,5-diaminofluorescein diacetate (DAF-2, 5 μM, S0019, Beyotime, China) for NO, which was prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide. Images were collected on a fluorescence microscope (DMIL LED Fluo, Leica, Germany).

6.6 Nitrite to Measurement in PVAT

NO production in PVAT was detected using a nitrite assay kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (S0023, Beyotime, China). Briefly, thoracic aortic PVAT was homogenized in cold tissue lysis buffer (S3090, Beyotime, China). The standard or samples was added to the 96-well assay plate with flavin adenine dinucleotide, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH), and nitrate reductase was added in turn, mixed, and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Then, lactate dehydrogenase was added to remove excess NADPH, and the Griess reagent was added in a ratio of 1:1. The absorbance at 540 nm was measured using a microplate reader (Epoch2, Bio Tek, USA). NO production in the samples was calculated according to the standard curve.

6.7 Western Blot

Thoracic aortic PVAT was homogenized in cold RIPA lysis buffer (P0013B, Beyotime, China) containing 1 mM PMSF (ST507, Beyotime, China), phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (AB201115, Abcam, UK), and protease inhibitor cocktail (5,892,791,001, Roche, Switzerland). After centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, the resulting supernatant obtained as total protein was used for subsequent detection. Protein extracts (40 μg) were separated by SDS–PAGE, and proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes with a pore size of 0.2 μm (ISEQ00010, Millipore, USA) using a Mini Trans-Blot Cell system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5% BSA (BS114, Biosharp, China) in TBST buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl with 0.1% Tween 20), and were then incubated overnight at 4 ℃ with the primary antibodies anti-eNOS (1:1000, ab199956 Abcam, USA), anti-peNOS Ser1177 (1:750, #771911156, Sigma Aldrich, USA), anti-Akt (1:1,000, 4691, Cell Signaling Scientific, USA), anti-pAkt Ser 473 (1:750, 4060, Cell Signaling Scientific, USA). Blots were then washed in TBST buffer and incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-Rabbit IgG (1:3000, A0545, Sigma Aldrich, and USA) for one hour. After washing in TBST buffer, the immune complexes were visualized using ECL (32,209, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and luminescence instrument hardware and software (5200, Tianon, China). The intensity of the bands was quantified using ImageJ software (NIH, USA). The membranes were used to determine GAPDH protein expression as an internal control using a rabbit anti-GAPDH (1:1000, G9545, Sigma Aldrich, and USA).

6.8 Statistical Analyses

All values are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the least significant difference (LSD) test was used to assess differences between groups; a paired t test was used to compare the vascular contractions with and without PVAT from the same intervention group. P < 0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS 22 software (IBM, USA). Figures were obtained using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad, USA).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Akt:

-

Protein kinase B

- BG:

-

Blood glucose

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- DAF-2:

-

4,5-Diaminofluorescein diacetate

- DAPI:

-

Destination access point identifier

- Emax :

-

Maximum contraction

- eNOS:

-

Nitric oxide synthase

- H&E:

-

Hematoxylin and eosin staining

- HDL:

-

High-density lipoprotein

- HOMA-IR:

-

Insulin resistance

- HS-CRP:

-

HYpersensitive C-reactive protein

- IL-6:

-

Interleukin-6

- Ins:

-

Insulin

- LDL:

-

Low-density lipoprotein

- NO:

-

Nitric oxide

- PE:

-

Phenylephrine

- pEC50/ pIC50 :

-

Potency values

- PVAT:

-

Perivascular adipose tissue

- SNP:

-

Sodium nitroprusside

- TC:

-

Cholesterol

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- TNF-α:

-

Tumor necrosis factor-α

- VAT:

-

Visceral adipose tissue

References

Di Angelantonio E, Bhupathiraju SN, Wormser D, Gao P, Kaptoge S, et al. Body-mass index and all-cause mortality: individual-participant-data meta-analysis of 239 prospective studies in four continents. Lancet. 2016;388(10046):776–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30175-1.

Collaborators GO. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):13–27. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1614362.

Coutinho T, Goel K, Corrêa de Sá D, Kragelund C, Kanaya AM, et al. Central obesity and survival in subjects with coronary artery disease: a systematic review of the literature and collaborative analysis with individual subject data. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(19):1877–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.058.

Szasz T, Bomfim GF, Webb RC. The influence of perivascular adipose tissue on vascular homeostasis. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2013;9:105–16. https://doi.org/10.2147/vhrm.S33760.

Marchesi C, Ebrahimian T, Angulo O, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling and perivascular adipose oxidative stress and inflammation contribute to vascular dysfunction in a rodent model of metabolic syndrome. Hypertension. 2009;54(6):1384–92. https://doi.org/10.1161/hypertensionaha.109.138305.

Fernández Alfonso MS, Gil Ortega M, García Prieto CF, Aranguez I, Ruiz Gayo M, et al. Mechanisms of perivascular adipose tissue dysfunction in obesity. Int J Endocrinol. 2013;2013:402053. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/402053.

Rafikov R, Fonseca FV, Kumar S, Pardo D, Darragh C, et al. eNOS activation and NO function: structural motifs responsible for the posttranslational control of endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity. Endocrinol. 2011;210(3):271–84. https://doi.org/10.1530/joe-11-0083.

Xia N, Horke S, Habermeier A, Closs EI, Reifenberg G, et al. Uncoupling of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in perivascular adipose tissue of diet-induced obese mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36(1):78–85. https://doi.org/10.1161/atvbaha.115.306263.

Man AW, Zhou Y, Xia N, Li H. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the perivascular adipose tissue. Biomedicines. 2022;10(7):1754. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10071754.

Agarwal SK. Cardiovascular benefits of exercise. Int J Gen Med. 2012;5:541–5. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijgm.S30113.

Boa BCS, Yudkin JS, van Hinsbergh VWM, Bouskela E, Eringa EC. Exercise effects on perivascular adipose tissue: endocrine and paracrine determinants of vascular function. Br J Pharmacol. 2017;174(20):3466–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.13732.

Saxton SN, Toms LK, Aldous RG, Withers SB, Ohanian J, et al. Restoring perivascular adipose tissue function in obesity using exercise. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2021;35(6):1291–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10557-020-07136-0.

Araujo HN, Victório JA, Valgas da Silva CP, Sponton ACS, Vettorazzi JF, et al. Anti-contractile effects of perivascular adipose tissue in thoracic aorta from rats fed a high-fat diet: role of aerobic exercise training. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2018;45(3):293–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1681.12882.

Sousa AS, Sponton ACS, Trifone CB, Delbin MA. Aerobic exercise training prevents perivascular adipose tissue-induced endothelial dysfunction in thoracic aorta of obese mice. Front Physiol. 2019;10:1009. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2019.01009.

Liao J, Yin H, Huang J, Hu M. Dysfunction of perivascular adipose tissue in mesenteric artery is restored by aerobic exercise in high-fat diet induced obesity. J Clinical Experimental Pharmacology Physiology. 2021;48(5):697–703. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1681.13404.

Meziat C, Boulghobra D, Strock E, Battault S, Bornard I, et al. Exercise training restores eNOS activation in the perivascular adipose tissue of obese rats: Impact on vascular function. Nitric Oxide. 2019;86:63–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.niox.2019.02.009.

Sousa AS, Sponton ACS, Delbin MA. Perivascular adipose tissue and microvascular endothelial dysfunction in obese mice: Beneficial effects of aerobic exercise in adiponectin receptor (AdipoR1) and peNOS (Ser1177). Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2021;48(10):1430–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1681.13550.

Wang XL, Zhang L, Youker K, Zhang M-X, Wang J, et al. Free fatty acids inhibit insulin signaling–stimulated endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation through upregulating PTEN or inhibiting Akt kinase. Diabetes. 2006;55(8):2301–10. https://doi.org/10.2337/db05-1574.

Otaka N, Shibata R, Ohashi K, Uemura Y, Kambara T, et al. Myonectin is an exercise-induced myokine that protects the heart from ischemia-reperfusion injury. Circ Res. 2018;123(12):1326–38. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313777.

Fujita S, Rasmussen BB, Cadenas JG, Drummond MJ, Glynn EL, et al. Aerobic exercise overcomes the age-related insulin resistance of muscle protein metabolism by improving endothelial function and Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling. Diabetes. 2007;56(6):1615–22. https://doi.org/10.2337/db06-1566.

Green DJ, Hopman MT, Padilla J, Laughlin MH, Thijssen DH. Vascular adaptation to exercise in humans: role of hemodynamic stimuli. Physiol Rev. 2017;97(2):495–528. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00014.2016.

Avolio A, Deng FQ, Li WQ, Luo YF, Huang ZD, et al. Effects of aging on arterial distensibility in populations with high and low prevalence of hypertension: comparison between urban and rural communities in China. Circulation. 1985;71(2):202–10. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.71.2.202.

Spradley FT, Ho DH, Pollock JS. Dahl SS rats demonstrate enhanced aortic perivascular adipose tissue-mediated buffering of vasoconstriction through activation of NOS in the endothelium. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2016;310(3):R286–96. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00469.2014.

Aghamohammadzadeh R, Greenstein AS, Yadav R, Jeziorska M, Hama S, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on human small artery function: evidence for reduction in perivascular adipocyte inflammation, and the restoration of normal anticontractile activity despite persistent obesity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(2):128–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.027.

Casey DP, Ueda K, Wegman-Points L, Pierce GL. Muscle contraction induced arterial shear stress increases endothelial nitric oxide synthase phosphorylation in humans. Am J Physiol-Heart Circulat Physiol. 2017;313(4):H854–9.

Araujo HN, Valgas da Silva CP, Sponton ACS, Clerici SP, Davel APC, et al. Perivascular adipose tissue and vascular responses in healthy trained rats. Life Sci. 2015;125:79–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2014.12.032.

Balligand JL, Feron O, Dessy C. eNOS activation by physical forces: from short-term regulation of contraction to chronic remodeling of cardiovascular tissues. Physiol Rev. 2009;89(2):481–534. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00042.2007.

Touati S, Meziri F, Devaux S, Berthelot A, Touyz RM, et al. Exercise reverses metabolic syndrome in high-fat diet-induced obese rats. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(3):398–407. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181eeb12d.

Hambrecht R, Adams V, Erbs S, Linke A, Krankel N, et al. Regular physical activity improves endothelial function in patients with coronary artery disease by increasing phosphorylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation. 2003;107(25):3152–8. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000074229.93804.5C.

Zhang QJ, Li QX, Zhang HF, Zhang KR, Guo WY, et al. Swim training sensitizes myocardial response to insulin: Role of Akt-dependent eNOS activation. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75(2):369–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.04.015.

Watts SW, Darios ES, Contreras GA, Garver H, Fink GD. Male and female high-fat diet-fed Dahl SS rats are largely protected from vascular dysfunctions: PVAT contributions reveal sex differences. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2021;321(1):H15-h28. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00131.2021.

Wang CYJK. Liao, a mouse model of diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;821:421–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-61779-430-8_27.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant numbers: 31971105 and 31801005].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CW: performed the experiment, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript; JZ: performed the experiment and analyzed the data; DG and YW: performed the experiment and collected tissue samples from rats; LG, WL and NS: performed exercise intervention; RC and HW: analyzed the data; JH: critically revised the manuscript; JL and MH: designed the study, interpreted the data, and provided administrative, technical, and material support; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Ethics approval

All animal experiments were performed with approval from the Ethics Committee of Guangzhou Sport University (No. 2021DWLL-13).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, C., Zhou, J., Gao, D. et al. Effects of Long-Term Aerobic Exercise on Perivascular Adipose Tissue Function and Akt/eNOS/NO Pathway in Obese Rats. Artery Res 29, 34–45 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44200-023-00032-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44200-023-00032-6