Abstract

Objectives

In clinical practice, clinicians usually ignore the possibility of a rare genetic disease, i.e., Dubin-Johnson Syndrome (DJS), for conjugated hyperbilirubinemia caused by a mutation in the ABCC2 gene or in the MRP2 protein. Therefore, the objective is to alert the readers about our third reported case of DJS in Pakistan. Moreover, we also want to draw the attention of health professionals to potential pharmacotherapeutic management of DJS, and the management of the potential increased susceptibility to drug toxicity.

Case report

We present a case of 23 years old Asian man, with unexplained persistent conjugated hyperbilirubinemia and normal liver transaminases. In 1999, the patient was admitted to a tertiary care hospital for raised conjugated bilirubin (CB), i.e., 67% of total bilirubin (CB; 11 mg/dl, total bilirubin; 16.4 mg/dl). After 19 years, in 2018, during regular checkup by a family physician, the CB was 73% of total bilirubin (CB; 3 mg/dl, total bilirubin; 4.1 mg/dl), while the results of other clinical tests were unremarkable. Soon after 3 years, in 2021, the patient visited a gastroenterologist for jaundiced eyes. Comprehensive clinical tests (CB was 53% of total bilirubin) were accomplished to exclude the other causes of conjugated hyperbilirubinemia, and DJS was diagnosed.

Conclusions

In summary, it is strongly recommended that the cases of unexplained persistent conjugated hyperbilirubinemia should be evaluated for the presence of DJS. Similarly, the drugs that increase the clearance of CB could prove to be a potential management strategy for cases that negatively affect patient’s quality of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The conjugated hyperbilirubinemia is a pathological elevation of conjugated bilirubin (CB) in a concentration higher than 20% of total bilirubin or a concentration higher than 2 mg/dL [1].

Bilirubin is a well-established marker of liver dysfunction and is usually associated with abnormal liver transaminases [2]. In the absence of disabling symptoms of conjugated hyperbilirubinemia with normal liver transaminases, clinicians usually ignore the possibility of Dubin-Johnson syndrome (DJS). This is one of the reasons that explain or justify that, until now, only two cases of DJS have been reported in Pakistan [3, 4].

DJS is a rare hereditary autosomal recessive disorder caused by a mutation in the ABCC2 gene or in the MRP2 protein and characterized by chronic conjugated hyperbilirubinemia with no alteration in liver transaminases. The affected gene is responsible for the secretion of CB into the bile. Though the structure of the liver is normal, there is an accumulation of dark, coarse pigment in the centrilobular hepatocytes, making the appearance of the liver black [5]. The typical clinical tests for diagnosis of DJS are either genetic study and/or urinary coproporphyrin analysis associated with hepatic biopsy [5]. In the absence of these clinical tests, differential diagnosis could be used to investigate DJS and thus exclude the other causes of conjugated hyperbilirubinemia [1].

In clinical practice, cases of DJS with mild conjugated hyperbilirubinemia do not need any pharmacotherapy. However, in cases that negatively affect patient’s quality of life, there is a need for an effective treatment that is still lacking.

Objective

The objective is to alert the readers about our third reported case of DJS in Pakistan. Moreover, we also want to draw the attention of health professionals to potential pharmacotherapeutic management of DJS, and the management of the potential increased susceptibility to drug toxicity.

Case report

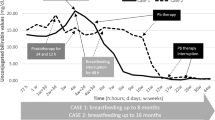

We present a case of a 23-year-old Asian man with unexplained persistent conjugated hyperbilirubinemia and normal liver transaminases. In 1999, the patient was admitted to a tertiary care hospital at 2 months for raised CB and total bilirubin of 11 mg/dl and 16.4 mg/dl respectively. The CB was 67% of total bilirubin, with elevated alkaline phosphatase, while the results of other tests, including liver transaminase, were unremarkable. The clinicians did not reach a definitive diagnosis, and phenobarbital was prescribed to induce the hepatic clearance of affected metabolites. The patient was discharged upon lowering of abnormal liver test values; CB and total bilirubin dropped to 4.7 mg/dl and 5.25 mg/dl respectively. The abnormalities in serum liver enzymes become normalized in subsequent years, but conjugated hyperbilirubinemia has persisted as well as its consequential minor jaundice.

After 19 years, in 2018, liver function tests and other clinical investigations were recommended during regular checkup by a family physician. This time the CB and total bilirubin was 3 mg/dl and 4.1 mg/dl respectively, i.e., CB was 73% of total bilirubin, and the ultra-sonography graph showed mild hepatomegaly. The results of other clinical tests were non-significant.

Subsequently, 3 years of the second exacerbation of conjugated hyperbilirubinemia, the patient visited a gastroenterologist for jaundiced eyes in 2021. Upon examination and review of the previous history, the hepatic biopsy was suggested to investigate the histopathological parameters. Still, it was not done due to the refusal of the patient to provide informed consent. Consequently, for a differential diagnosis, biochemical, serological, hematologic, urinary, endocrinological, and radiographic tests were accomplished to exclude the other causes (Table 1). The etiologies that has been excluded were disease related to obstruction of bile duct, intrahepatic cholestasis, acute, or chronic hepatic injury etc. [1, 6]. The CB and total bilirubin was 3.1 mg/dl and 5.9 mg/dl respectively, i.e., CB was 53% of total bilirubin. The FibroScan showed a controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) value of 202 db/m (reference; 100–400 db/m) and E value of 6.1 kPa (reference 2.5–7 kPa).

Diagnosis of conjugated hyperbilirubinemia was made with suspicion of DJS or Rotor syndrome. The urinary determination of coproporphyrin that is used for differential diagnosis between DJS and Rotor syndrome [5] was not commercially available. In the end, we have compared the patient’s clinical and pathological features with previously reported DJS patients, and the findings were consistent with our case [7]. Moreover, expected serum unconjugated bilirubin level in DJS and Rotor syndrome is up to 6.7 mg/dl, and 1.7 mg/dl respectively [8]. In our case, mean serum unconjugated bilirubin was 3.1 mg/dl. The data related to the clinical tests of the case is presented in Table 1 and Figs. 1 and 2.

Discussion

Although in scientific research, case reports are not at the top of the list, on the other side, they are the only source to report the most relevant and rare clinical events. However, we took this work to highlight the third case of DJS in Pakistan. It could be helpful to identify potential therapeutic agents for the management of DJS cases that negatively affect patient’s quality of life. Therefore, we expect more detailed clinical studies designed to work on the mentioned grey areas in the future.

The previous two reports of DJS in Pakistan were reported in Sheikh Zayed Hospital, Lahore, of a child age 6 years in 1997, and Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi, of an adult male age 28 years in 2008, respectively [3, 4]. The stated prevalence of DJS is 1/1300 [9], thus we suppose that the Pakistan’s reported data is much lower than the actual cases. It could be attributed to either underdiagnosis and/or underreporting.

Due to the benign nature of DJS, there is no progression to fibrosis or cirrhosis and therefore no medical treatment is required [5]. The therapy for mild to moderate cases of DJS is only limited to non-pharmacological interventions. However, in cases where the abnormal level of CB is disabling the daily patient’s life, one should consider a more effective medical therapy, about which there are no established consensus in the literature yet. Nevertheless and acknowledging the theoretical pharmaceutical principles, we expect that drugs which induce the CB clearance could prove a potential favorable therapeutical approach for some selected cases of DJS. There is evidence that CB clearance inducers proved to normalize the abnormal liver test values. Phenobarbital stimulates a gene for the UGT1A1 and reduces the serum bilirubin levels (Both total and CB) by 25% [10]. In our case, 57% and 67% reduction was noted in serum values of CB and total bilirubin after administration of phenobarbital. Similarly, ursodeoxycholic acid and metalloporphyrins can also prove helpful in lowering the abnormal CB values [10].

As DJS is related to the malfunction of a transporter protein MRP2, we believe that drug substrates of MRP2 transporter protein should be carefully and suitably managed by a healthcare medical specialist. Some examples are cisplatin, etoposide, vinca alkaloids, anthracyclines, camptothecins etc. [11]. In 2021, John et al. concluded that a standard protocol need to be followed for DJS in case of anesthetics administration due to potential drug-disease interactions [12].

As previously discussed, both genetic testing and/or urinary coproporphyrin analysis (total urinary coproporphyrin and isomer I/III quantification) are used for differential diagnosis between Dubin-Johnson and Rotor syndromes [5]. But due to the rare nature of our disease, to date, these tests are not commercially available in Pakistan and most other countries. Hepatic biopsy can also be an option to investigate the unique histopathology of DJS [5]. But then again, with the involvement of interventional procedure and cases where the DJS symptoms are not disabling, the affected patients are generally not willing to give informed consent for hepatic biopsy. Similarly, when considering medical and ethical factors, it is crucial to evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of a particular clinical test. If a test would not contribute to enhancing health results, it is best to avoid performing it. This is why in the three reports in Pakistan, including our case, the diagnosis of DJS was made differentially and based only on clinical experience. In this case, an attempt was made to perform the laboratory tests of urinary coproporphyrin analysis in several research institutes. The applied protocol was the one from Respaud et al. 2009, yet still, no satisfactory results were obtained due to the unavailability of a fluorescent detector coupled with high-performance liquid chromatography [13]. Although the diagnosis of DJS was considered based mostly on the clinical features of the case [7], we believe that the followed protocol was not standardized and therefore it is important to mention it as a current limitation of the presented study.

Conclusion

In Pakistan, as the worldwide trend, epidemiological data on the DJS is scarce, mostly due to the dependence of clinicians on empirical therapy and/or underreporting. Therefore, it is recommended that the cases of unexplained persistent conjugated hyperbilirubinemia with normal liver transaminases should be evaluated for the presence of DJS in clinical practice. Similarly, the drugs which increase the clearance of total and CB can prove to be a potential therapeutic management for cases of DJS that negatively affect patient’s quality of life, however, future studies are warranted on this aspect. Moreover, the pharmacokinetics of drugs that require CB for their disposition could be modified in DJS as this condition is related to the malfunction of MRP2 transporter. Therefore, we believe that drug substrates of MRP2 protein should be cautiously managed among the affected patients.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Tripathi N, Jialal I. Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

Ruiz ARG, Crespo J, Martínez RML, et al. Measurement and clinical usefulness of bilirubin in liver disease. Adv Lab Med. 2021;2(3):352–61.

Nisa AU, Ahmad Z. Dubin-Johnson syndrome. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2008;18(3):188–9.

Hussain W, Qureshi D, Maqbool S. Dubin Johnson Syndrome. Pak Paed J Jan. 1997;21(1):43–4.

Talaga ZJ, Vaidya PN. Dubin Johnson Syndrome. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

Strassburg CP. Hyperbilirubinemia syndromes (Gilbert-Meulengracht, Crigler-Najjar, Dubin-Johnson, and Rotor syndrome). Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24(5):555–71.

Togawa T, Mizuochi T, Sugiura T, et al. Clinical, pathologic, and genetic features of neonatal Dubin-Johnson syndrome: a multicenter study in Japan. J Pediatr. 2018;196:161–7.

Wagner KH, Shiels RG, Lang CA, Seyed Khoei N, Bulmer AC. Diagnostic criteria and contributors to Gilbert’s syndrome. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2018;55(2):129–39.

Shani M, Seligsohn U, Gilon E, et al. Dubin-Johnson syndrome in Israel. I. Clinical, laboratory, and genetic aspects of 101 cases. Q J Med. 1970;39:549–67.

Singh A, Koritala T, Jialal I. Unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

Yu XQ, Xue CC, Wang G, et al. Multidrug resistance associated proteins as determining factors of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of drugs. Curr Drug Metab. 2007;8(8):787–802.

John AA, Shibli KU, Soliman MH, et al. Anesthetic management of a patient with known Dubin Johnson Syndrome – a case report. Anaesth Pain Intensive Care. 2021;25(5):676–9.

Respaud R, Benz-De Bretagne I, Blasco H, et al. Quantification of coproporphyrin isomers I and III in urine by HPLC and determination of their ratio for investigations of multidrug resistance protein 2 (MRP2) function in humans. J Chromatogr B. 2009;877(30):3893–8.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: SK and DA. Literature search and data analysis: SK, DA, and SUR. Writing—original draft preparation: SK. Writing—review and editing: SUR. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The patient has given written consent for publication.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, S., Ali, D. & Rehman, S.U. A case report of unexplained persistent conjugated hyperbilirubinemia with normal liver transaminases over 23 years: remember Dubin-Johnson syndrome!. J Rare Dis 2, 10 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44162-023-00014-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44162-023-00014-x