Abstract

Aim

Families from socioeconomically deprived backgrounds appear to have been greatly impacted and face worsening inequalities as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. With more than half of children in Newham, East London, living in poverty, this study aimed to investigate the impact of the COVID-19 lockdowns on families with a child under 5 years-old in Newham and identify their immediate needs to inform recovery efforts.

Subjects and methods

This was a qualitative study. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 13 participants (2 fathers; 11 mothers) exploring the impact of the COVID-19 lockdowns on family life, neighbourhood and community and important relationships in the child’s world.

Results

All parents experienced significant impacts on family life and well-being because of the pandemic. Families were placed under increased stress and were concerned about the impacts on child development. Low-income families were most disadvantaged, experiencing lack of professional support, community engagement and inadequate housing.

Conclusion

Families were placed under increasing pressure during the pandemic and recovery efforts need to target those most affected, such as families from low-income households. Recovery efforts should target child social and language development, family mental health, professional service engagement and community involvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused unprecedented and unpredictable disruption to family life and placed greater demands on families [1]. Many families experienced increased financial insecurity, i caregiving burdens and stress associated with the demands of physical distancing [2]. In the UK, lockdown began on 23 March 2020 and involved the closure or nurseries and preschools, schools, workplaces, non-essential shops and businesses and reduced health and social care provision as well as restrictions on daily activities. Subsequent easing of restrictions from June 2020 was punctuated with reintroduction of mobility restrictions in response to fluctuating virus rates. In October 2020, a three-tiered (low to high alert) approach with escalating restrictions was introduced in response to increased virus rates.

Lockdowns restricted social and mobility freedoms and meant families had to stay at home, in close proximity for long periods of time, often without vital support. Lockdowns have directly impacted child outcomes through disruption and closures of key services for children as well as indirectly through negative impacts on parental well-being and family functioning [3]. This global health crisis has become a major social and economic crisis [4] that will have significant consequences for family’s income and employment [5] and well-being [6].

While the literature has highlighted challenges faced by families of various compositions, an underexplored facet remains—the nuanced implications for families with children under the age of 5. Early childhood (birth—5 years-old) is a critical period in development, where family interactions play a paramount role in shaping child outcomes [7]. Infants born during or just before the pandemic faced unique challenges having missed crucial opportunities to connect with extended family members and family friends [8]. Parents have reported increased levels of infant distress, manifesting as increased crying and clinginess, underscoring the early and profound social implications of the pandemic [9]. Furthermore, children who are not in school have also been found to be less physically active, have poorer sleep and spend more time in front of screens [10].

Understanding the multi-faceted impacts of the pandemic on families with young children is critical to shape and target long-term recovery efforts.

1.1 Education disruptions and behavioural changes

The closure of early education and care services (ECEC) and restrictions on social interaction and mobility implemented across the UK have resulted in limited opportunities for young children to engage in formal and informal education, socialising and outside play [11, 12], all of which have been associated with uncertainty and anxiety in children [13,14,15]. A cross-sectional study conducted in Brazil with 153 caregivers of children under 5 revealed that the pandemic increased stressors such as low family income, unemployment, and heightened levels of sadness, depression, and anxiety among caregivers [16]. Caregivers reported challenges with offering age-appropriate play activities and organising care routines for children at home. Preschoolers, in particular, exhibited more misbehaviour, aggressiveness, and agitation compared to infants or toddlers.

Globally, the closure of schools had mixed effects, as evidenced by a rapid systematic review of studies published between January and September 2020 [17]. While there was a decline in hospital admissions and paediatric emergency visits, many children lost access to essential school-based healthcare services, services for children with disabilities, and nutrition programs. The prolonged closure and reduction in physical activity also contributed to increased anxiety, loneliness, and various stressors, underscoring the importance of identifying and supporting vulnerable children during such times.

The practice of shared book reading, a nurturing support for early development, was impacted by the closures of childcare, early education programmes and children’s centres [18]. A survey of American parents with children aged 2 to 5 revealed a significant increase in screen-mediated reading and a decrease in the number of adults regularly reading with children. While families adapted to virtual options for story time, these changes may have lasting effects on the nature of shared reading and, consequently, children's typical learning experiences.

1.2 Psychological and behavioural impacts

Research consistently highlights the profound psychological and behavioural impacts of the pandemic, affecting both children and caregivers. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Panda et al. [19] revealed a significant percentage of children under the age of five suffering from anxiety, depression, irritability, and inattention. Caregivers, too, experienced heightened levels of anxiety and depression. These findings underscore the urgent need for well-informed public policies aimed at supporting parents and, crucially, their children in the early years, during and after the pandemic.

A national survey conducted in the United States in June 2020highlighted a substantial decline in the physical and emotional well-being of parents and children under 5 years-old, with nearly 1 in 10 families reporting worsening mental health [20]. Challenges such as the loss of regular childcare, changes in insurance status, and worsening food security were particularly acute for families with children in their formative years. Policymakers are urged to give due consideration to these unique needs as they formulate strategies to alleviate the health and economic effects of the ongoing pandemic [21].

Following the model proposed by Prime and colleagues [2], families experiencing heightened pandemic-related disruption face greater family dysfunction and increased child mental health problems. This, in turn, leads to poorer parental mental health and less optimal parenting behaviour over time [22]. Parents reporting more COVID-19-related stressors, such as work or economic changes, observed their young children exhibiting heightened levels of anxiety, withdrawal, fearfulness, and acting out [23]. Internationally, families encountered similar challenges related to child adjustment, including increased levels of child hyperactivity, conduct and emotion problems, particularly in families characterised by heightened levels of parent distress, parent–child conflict, and household chaos [24].

The toll of the pandemic on the mental health of children and adolescents is further exemplified in a nationwide representative study conducted in Germany, the BELLA cohort study [17]. The research, encompassing 1586 families, found significantly lower health-related quality of life, heightened mental health problems, and increased anxiety levels were reported compared to the pre-pandemic period. Notably, children with low socioeconomic status, a migration background, and limited living space were disproportionately affected, emphasising the imperative for targeted health promotion and prevention strategies tailored to the unique needs of these vulnerable populations.

1.3 Changes in family dynamics

The well-being of family members is contingent upon family climate and relationships [25]. Prime and colleagues [2] proposed a model of the impact of COVID-19 on children’s adjustment via family functioning. The model suggests that the pandemic will have a cascading influence on child adjustment. That is, social disruption will result in heightened levels of distress for parents that will in turn impact relationships between parents and children and indirectly impact sibling relationships. Children may therefore not experience the positive family interactions needed for positive development. Pre-existing vulnerabilities within families may increase their susceptibility to social disruption.

1.4 Economic distress and family well-being

Lockdown restrictions reduced parents access to vital support networks and caused psychological distress, especially for low-income parents [26]. Parental well-being may mediate the impact of the pandemic on family functioning via changes to marital, parent–child and sibling relationships [27]. Families from lower income households reported higher levels of psychological distress [26] and with worsening financial negative perceptions of lockdown they reported poorer intra-family relationships and poorer child socio-emotional development [28]. Families who experienced lost wages or lost a family member due to COVID-19 were more likely to not experience improvement in family relationships [29]. In contrast, healthy communication and finding positive family activities to build a sense of togetherness supported family well-being [21]. Family relationships can therefore be a risk factor or a source of resilience.

Reduced access to key services exacerbated the negative impacts of the pandemic on children from low-income households. School closures for example had a greater impact on disadvantaged children [28]. Children from low-income households were less likely to be able to access remote learning due to insufficient devices or unreliable internet connections [30] and their parents were more likely to be going out to work and therefore unable to assist with home-schooling [31]. Further, children from lower income households were more likely to substitute school with activities such as TV or video games [32]. The learning gap between low- and high-income children may consequently be exacerbated in the wake of the pandemic.

The economic distress caused by the pandemic, even for families with no income loss, had profound social implications. A survey of 572 low-income families with preschool aged children in Chicago found that parental job and income losses were associated with increased parent depressive symptoms, stress, diminished sense of hope and negative interactions with children [33]. These findings emphasise the complex interplay of economic and social factors.

Challenges associated with social and mobility restrictions are likely to be compounded by housing. Lower income families are more likely to live in smaller-sized accommodation which is likely to have detrimentally effected health and well-being during the pandemic, particularly during lockdown. In 2020, 7% of people from the most deprived UK households lived in overcrowded housing, compared to under 0.5% of those in the least deprived households [34]. In poorer households, parents may have lacked space for their children to play during the UK’s ‘stay at home’ order, with one in five households having no garden access. Immigrant families were also disproportionately impacted by the pandemic; they faced a pile up of financial and relationship stressors including job loss, housing insecurity, and constraints to accessing resources (e.g. language barriers, lack of technology) [35].

1.5 The present study

The COVID-19 pandemic has had far-reaching consequences for families with young children, affecting their daily routines, mental health, and overall well-being. Understanding these impacts is crucial for policymakers and practitioners to develop targeted interventions that address the specific needs of families, especially those facing heightened vulnerabilities during these challenging times. While recognising the impact on families with children of all ages, the pandemic may have had more severe consequences for families with young children, who are especially sensitive to developmental inputs. Understanding these nuanced dynamics is essential to developing targeted interventions that mitigate the potential long-term consequences on child outcomes.

This qualitative study consequently aimed to explore the intricacies of the pandemic's impact on families with young children, unravelling the challenges faced and identifying areas where recovery efforts are most urgently required. By doing so, we contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the far-reaching implications of the COVID-19 pandemic on family life, particularly in the context of early childhood development. The primary research question was to identify the indirect impacts of the pandemic on families with a child under 5 years-old due to the limited focus on this foundational period in development. A secondary research question was to compare the experience of lockdown between families from different household income levels as research has indicated that low-income families may be more negatively impacted.

2 Methodology

2.1 Setting

This project was based in the Borough of Newham in East London. Before the pandemic, an estimated 52% of children in Newham lived in poverty, the highest figure for any London Borough [36]. A quarter of households are overcrowded in Newham, compared to 4.5% across England and Wales. Newham’s highly diverse population profile is 45% Asian, with a total of 68% who are not White British [37], the highest proportion for any local authority. It also has the lowest proportion of people speaking English as their main language of all local authorities [38]. Without early intervention, these factors may increase susceptibility to worsening socioeconomic inequalities resulting from the pandemic [39]. Newham’s diverse population profile provides an opportunity to explore how families have deployed their interpersonal, social and economic resources to manage the risks associated with the lockdown and its aftermath.

2.2 Sample

This study was nested within the UKPRP ActEarly programme, based in Tower Hamlets and Bradford, which aims to provide early intervention to improve the long-term health and wellbeing of children [40].

An online community survey was carried out between August and December 2020 with 2054 parents of children under 5 years-old and those expecting a baby via borough Public Health and council services. The survey was based on the Families in Tower Hamlets survey [41]. Participants who expressed a willingness to participate in an interview in the survey were recruited. Inclusion criteria for the present study included being a resident of Newham and being the parent of at least one child under 5 years old. Participants who were expecting their first child were excluded from the study.

Sample stratification primarily focused on income due to the inequality in the impact of COVID-19 across household income levels [42] and the aim to focus on those more severely affected by COVID-19 [31]. A higher proportion of participants from low-income households (< £20,799) were therefore selected. Household income bands were selected to match the distribution of the sample and taking into account local median household income [43]. A secondary stratification factor was self-identified ethnicity to capture a range of ethnicities in this multi-ethnic context. Three main ethnic groups were selected: White British and Irish, Asian (including Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi) and Black (including Black African and Caribbean). These ethnic subgroups were chosen as they were the predominant ethnicities within Newham, and Asian and Black groups had been identified by the Newham Public Health team as experiencing worse socio-economic and mental health outcomes. Table 1 outlines participant characteristics of the final sample. However, although we attempted to recruit an ethnically representative sample due to the limited size of the final sample, we were not able to consider this dimension within the analysis.

A random stratified sample (n = 56) of eligible participants was identified from the quantitative survey (n = 1925). Participants were offered a £20 incentive voucher for participating, in accordance with INVOLVE guidelines [44]. Interviews were scheduled with 15 participants; the remaining 41 participants declined to participate or were non-responsive. Thirteen participants completed interviews and the remaining two participants became non-responsive.

2.3 Interviews

One researcher (EM) conducted semi-structured interviews that lasted approximately one hour. The topic guide from the Families in Tower Hamlets study was used [41]. The topic guide consisted of five main areas: (1) changing life for the better; (2) adult’s daily family life during COVID-19; (3) children’s daily family life during COVID-19; (4) neighbourhood and community; and (5) important people in the child’s life. Participants were asked to recount how life has changed since the pandemic under each of these topics in relation to the target child under 5 years-old. The topic guide was piloted with three external volunteers who did not form part of the final sample. Due to social distancing restrictions, interviews were conducted via video or voice calling. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

2.4 Analysis

We conducted a thematic analysis using a combined deductive and inductive coding approach [45, 46].

The lead author (EM) worked iteratively and collaboratively with the Families in Tower Hamlets team to complete the analysis to ensure a cohesive approach across both studies. An initial coding framework was developed based on the topics and categories from the interview guide. The team applied this framework to a subset of 5 transcripts. EM met regularly with the Families in Tower Hamlets team to discuss and refine the coding framework and incorporate emergent codes and categories. The final framework was then tested and refined on the complete dataset. Codes were then categorised into overarching themes [45]. All data were managed and analysed using NVivo 20.

2.5 Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study received ethical approval from [university] Research Ethics Committee (REC1366) and the NHS Health Research Authority (20/LO/1039). The research was conducted in accordance with institutional ethical guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

3 Findings

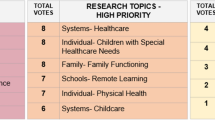

The final sample consisted of 13 participants (2 fathers and 11 mothers); Table 1 shows the ethnicity, socio-economic status and gender characteristics of participants.

The thematic analysis resulted in three main themes: (1) child’s life; (2) sources of stress; (3) support networks.

3.1 Child’s life

Children’s routines and development. Following the closure of ECEC, many participants experienced disruption to their daily routines, particularly bedtime routines, as the increased time spent at home with children altered the usual structure of their day and required parents to care for and provide stimulation for their children when they previously would have been in ECEC.

“When we hit the pandemic I think it feels like his bedtime routine kind of went out the window a bit”

ID12—Low income, White ethnicity, Female

Establishing a routine resulted in participants feeling more positive about their child’s life because they felt the routine provided consistency and meant their children were being engaged and occupied. The act of consciously structuring their children's time not only addressed immediate challenges but also served as a proactive measure to promote a sense of normalcy and well-being during these unprecedented times.

In essence, the experience highlights the resilience and adaptability of families as they navigated the disruptions caused by the closure of ECEC facilities. It emphasizes the importance of routine in fostering a positive environment for children and underscores the proactive steps taken by parents to create a sense of stability amid the uncertainties of the pandemic.

The closures of ECEC meant many participants felt that their children had missed out on opportunities to gain vital communication and social skills. Participants were concerned that their children had spent limited time with those outside of direct family and about the detrimental impact of this on their speech and language development in the long-term. Participants were particularly concerned that their children had limited interaction with peers their own age which may impact their play and social skills. Further, participants said limited interactions with other children made it difficult to gauge how well their child was developing:

“She doesn’t like sharing at all. So if she had continuous time for nursery from September to now, then she would have gotten better with sharing, but I don’t think she has.”

ID3—Medium income, Asian ethnicity, Female

This sentiment underscores the participants' belief that consistent attendance at nursery or ECEC facilities would have played a pivotal role in fostering positive behaviours, such as sharing. The disrupted routine and limited social interactions during the pandemic may have hindered the development of important social skills, adding to parents' concerns.

Some participants reported that their child was struggling emotionally with the pandemic-related restrictions; they were expressing increased anxiety and outbursts as a result of lockdowns. Other participants reported their child found adjusting to going out after lockdowns anxiety inducing:

“He's shown a lot of anxiety, especially around people with death and dying, and he's quite aware that coronavirus is something that can...he phrases it as ‘make people die’”

ID10—Medium income, White ethnicity, Female

These revelations shed light on the complex emotional responses of children to the disruptions caused by the pandemic. It further emphasizes the need for targeted interventions and support mechanisms to address the emotional well-being and developmental needs of children affected by the closures of ECEC facilities.

Child play. Most participants reported that their children were accessing outside spaces for play, such as their garden or local park. Outside play was felt to be the most enjoyable way to entertain children and keep them active. However, low-income participants were more greatly impacted by the closure of public outside play spaces as high-income participants more often had access to private gardens:

“It's really hard for the children. Because the schools are off. In the park like all the playing things are not open. So it's hard for them like staying at home or not playing outside and the school is off so it’s hard for them.”

ID6—Low income, Asian ethnicity, Female

Participants, especially from low-income households, felt that closing of outside spaces for children had not taken the needs of young children into account. Many participants felt that the limited playground access during the lockdowns had negatively impacted their children’s mental health.

There were income related differences in children’s spaces to play inside. High-income participants often described a number of rooms their children would play in, whereas low-income participants were often dissatisfied with the adequacy of their home environment and the lack of spaces for children to play:

“We have only one room. So she plays in our room. That's it. Sometimes she goes downstairs. She can play in the kitchen and in the corridor that's it.”

ID6—Low income, Asian ethnicity, Female

These findings underscore the importance of considering socio-economic factors in policymaking and resource allocation during crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Addressing the disparities in access to play spaces, both outdoor and indoor, is essential for promoting equitable opportunities for children's development and well-being.

3.2 Sources of Stress

Childcare and education. Looking after their children for long periods without respite was a common source of stress for participants. Many participants said they were constantly exhausted from looking after their children during lockdowns, particularly due to the lack of support from extended family and friends. The strain was palpable, and participants often described moments of frustration and fatigue, attributing it to the challenges of being a parent without the usual assistance from relatives:

“We had moments where we were just ratty but I think that's just being a burnt out parent to be honest as well, the exhaustion of being a parent, not having my mum to babysit for a while. That's been really hard.”

ID3—Medium income, Asian ethnicity, Female

Participants reported that home schooling was a major source of stress as they were required to educate their young children who had just started school (4 to 5 years-old in the UK) or were responsible for educating their older children. Parents reported the pressure of balancing work responsibility and home-schooling requirements. The dual roles of parent and educator took a toll on some participants, impacting their energy levels and straining their relationship with their children:

“Obviously home school was really challenging because… you're having to be another role to your kids as well. My daughter especially really didn't respond very well to mummy trying to be teacher… having to, I guess bring that like, work, and school, home...”

ID2—High income, White ethnicity, Female

Social restrictions. Social restrictions imposed during the pandemic contributed significantly to the stress experienced by families. Participants, especially those whose children were born just before or during the pandemic, expressed a sense of loss as extended family members missed out on crucial stages of their children's development. The limited interactions with grandparents and other relatives due to health concerns and lockdowns created emotional strains, further exacerbating the challenges faced by families:

“I only have seen my mum and my dad a handful of times because I

also caught COVID-19 as well, over a month ago, my two children caught it as well...”

ID12—Low income, White ethnicity, Female

These challenges underscore the need for comprehensive support systems for families, recognising the strain caused by disruptions in childcare, education, and social interactions.

Housing. Housing was a source of stress more specifically related to those of lower income. These participants tended to have problems with the maintenance of their homes, making it particularly difficult to create adequate play spaces for children:

“It's just not a great environment to raise children, and I feel like they

deserve a lot better. I mean we've had so many issues with damp, insects, even rats. And I'm yet to find a landlord that is willing to help.”

ID11—Low income, Asian ethnicity, Female

The substandard housing conditions reported by participants underscore the disparities in living situations, with some families facing dampness, insect infestations, and even rodent issues. The lack of timely and effective assistance from landlords further compounded the stress for those already struggling with financial constraints. Further, some participants mentioned that their inadequate housing situation led to difficulties maintaining privacy between adults and children.

The pandemic brought to light the existing inequalities in housing, with families of lower income disproportionately affected. The negative implications of these poor housing conditions, although pre-existing, were exacerbated in the pandemic when families were required to spend more time at home and utilise their home for activities such as work and education. Addressing these issues requires a multifaceted approach, incorporating policies that not only ensure safe and habitable living conditions but also consider the unique challenges posed by inadequate housing during public health crises.

3.3 Support networks

Changes to social networks. Restrictions on social interaction during the pandemic resulted in many participants feeling isolated from family and friends and without support. Some participants felt the pandemic had impacted their ability to develop existing friendships. Participants felt that if they were not in the pandemic they would have “struck up a better, stronger friendship” with other new parents (ID1).

The majority of participants resorted to online communication in order to maintain relationships with their extended family and friends. However, a number of participants reported struggling to maintain their young children’s attention on these calls, hindering the depth of interaction that might have been possible in person:

“We FaceTime, but they'll talk for a few minutes but… when you FaceTime someone to actually being in front of someone, it's different. They do sort of react different and they don't really… interact as much as they would if they'd seen them in person”.

ID1—Low income, White ethnicity, Female

The shift to online communication, while instrumental in bridging physical distances, brought about its own set of challenges, especially concerning engagement levels with young children. This aspect underscores the importance of recognising the limitations of virtual interaction, especially for families with young children, and highlights the need for strategies to address these challenges in fostering meaningful social connections.

Community Involvement and Services. Participants felt there was not a sense of community, and they did not know people in their local area as much as they would like. There was differential community involvement based on household income. High income participants were generally more involved in community events and initiatives (e.g. gardening groups), which allowed them to meet people and help others in the community. Low-income participants said they did not get involved in community initiatives because their time was taken up with work and childcare responsibilities:

“I see sometimes there’s a meeting but there’s no one to stay with the kids, so I don’t join them, because the time they do the meeting my husband is at work. Sometimes the meeting is at 5, 6, at this time I cannot leave the kids alone and go to a meeting. I am never able to attend them because the time is not that suitable for me.”

ID9—Low income, Black ethnicity, Female

For low-income families, community activities are often not prioritised because they are negotiating other challenges such as work, childcare, finances and housing; stressors that were exacerbated in the pandemic. For those in higher income households the burdens of these stressors were reduced resulting in greater availability to engage with community initiatives.

Middle- and high-income participants were less aware of services offered by children’s centres:

‘I haven’t got the slightest sense of what the children centres have to offer or you know local groups, community organisations, just nothing really.”

ID10—Medium income, White ethnicity, Female

Middle- and high-income participants may not be in need of these services as much as low-income participants who have less access to inside and outside play spaces.

A prominent concern for parents was the closure of local services, particularly those targeted at new mothers, and the resulting reduction in parental support and mental health implications this afforded. A number of participants discussed how they were missing out on services, such as mother and baby groups, and thereby losing out on vital opportunities to share experiences and receive support:

“The baby she… I mean I guess it doesn’t affect them too much and you know, I think it's more like new mums prefer to go out and meet other people 'cause you know, you actually learn a lot talking to new mums rather than…well than the baby learning it.”

ID7—High income, White ethnicity, Female

Parental support was thought to be important due to the isolation and stress of looking after young children in lockdowns, especially when they had to spend a significant amount of time at home without family support. Participants felt that mental health services were essential to preventing the long-term impacts of the pandemic on parent’s well-being.

“They need to support the parents more. Because, as I say, I felt so isolated and alone. If it wasn’t for that children centre, I would have been on my own.”

ID1—Low income, White ethnicity, Female

The majority of parents discussed the limited, virtual contact they experienced with their health visitor. Accessing health visitor support during the pandemic was a particular concern for low-income participants, leading to worry for their child’s development.

“Just make sure that you, if it ever happens again, that you need to support those children that are under five more. You know, I haven’t heard from my health visitor in 18 months. You know their two year review was done over the phone… I get it, but again, that's not ideal. There needs to be more support for those… they've sent out worksheets for the older kids. Send some things, for the ideas for the little ones to do, that don’t involve sitting in front of the computer. The Borough needs to support the youngsters more.”

ID1—Low income, White ethnicity, Female

4 Discussion

This study explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the lives of families with a child under 5 years-old living in an inner-city London borough in order to inform recovery efforts for the most vulnerable. The findings revealed that families, across household income levels, experienced significant impacts of the pandemic in relation to family and professional support, experienced increased stress from balancing home-schooling with work-commitments and felt their children’s social and language development was being detrimentally impacted. However, families from low-income households experienced particular challenges in relation to lack of indoor and outdoor spaces for their children to play, limited contact with health visitors and limited engagement with the community. Families with pre-existing vulnerabilities may consequently experience greater detrimental impacts of the pandemic.

Although prior research has indicated that parents from lower income backgrounds experience increased parental stress and were less able to support their young children’s education [26, 28], the current study found that irrespective of income level, participants experienced increased parental stress and concern regarding their child’s development and social participation during the pandemic. Participants were concerned about their child’s language development due to their limited interaction with others. A finding echoed in national research [47]. This is key as in the early years, children’s development is based on face-to-face interaction and outdoor play as they cannot maintain relationships via virtual means like older children [48]. Further, some participants noted their children had increased anxiety around others. This builds on earlier findings that 44% of early years providers have found that children’s emotional, social and personal development has fallen behind due to lockdown school closures [49] and highlights the need for recovery efforts to be focused on early social and language development. The distress and disruption caused by the pandemic may result in poorer parental wellbeing and lead to more dysfunction in the family and increased parent–child conflict which may impact child development and adjustment [22].

ECEC closures resulted in increased childcare pressures on families that impacted parent–child relationships. In this study, participants reported feeling frustrated with the need to look after their children for longer periods while often balancing work and other commitments. This was exacerbated by isolation from usual support systems due to the social restrictions of lockdown. Caregivers found home schooling their young children a source of significant stress and difficult to balance with their other responsibilities. A large-scale European study found that caregivers of younger children reported significantly more problems with home schooling than those of older children, resulting in substantial frustration for these caregivers and adverse effects on both parents and children [50]. Indeed, home-schooling strained the parent–child relationship, a key platform for early child development [2]. Families balancing employment and childcare responsibilities, especially in the context of employment and financial insecurity, may therefore have been facing a pile up of stressors. The need for more parental support in the context of isolation and parenting pressures in the lockdowns is therefore prominent. This conflict in the parent–child relationship may have prevented families forming a sense of togetherness and engaging in positive family interactions that would have been a source of resilience [21].

In addition to these global challenges faced by families, there were some socio-economic differences in relation to children’s play. While families in high-income households tended to have sufficient rooms in their home and outdoor space for their young children to play, those in low-income households generally felt that their home was inadequate for their children, causing stress and frustration. Inadequate housing may not only have practical implications such as spaces for children to play or study but may impact family health and well-being. A survey in Britain found that 31% of adults reported mental and physical health problems during the pandemic due to insufficient space or maintenance of their home [51]. The links between housing and financial insecurity and parental mental health may be stronger for low-income compared to middle- and high-income families as the consequence of these insecurities is greater [52]. Thus, although many families may have faced employment and housing related challenges during the pandemic the consequences for families with pre-existing economic vulnerabilities may be greater.

Most participants reported a lack of community atmosphere within the borough, leading to a lack of communal support at a critical time. Positive feelings towards one’s community was lowest during the pandemic in England [53], suggesting this experience may have been widespread. Similarly, participants often reported not being aware and therefore not involved with borough services. Many mothers were disappointed with the limited provision, consisting mainly of online services, during the pandemic. They felt this had left them without peer or professional support and advice. International policy suggests that support is necessary for maternal wellbeing [54] and professional postnatal care has been increasingly recognised in order to support parents and enable discussions around shared experiences [55]. Participants felt that parental support services, especially around mental health, were greatly needed in the wake of the pandemic.

Higher income families were often more involved in the community and may have thus benefited from the positive effects of this on quality of life [56]. In contrast, lower income families were generally not involved in community activities or initiatives due to their time being taken up with childcare responsibilities. This may reflect lack of social support for these families [11]. Social support is generally understood to be made up of homogeneity of network members and accessibility [57] and enables social integration and assistance. Engaging with a diverse community may therefore be a protective factor. Further, low-income families are often disproportionately negatively impacted by the stress of the pandemic [26], providing these families with social support may support parent mental health and in turn child outcomes.

There were differences in service access between those of lower and higher income. Low-income participants frequently reported challenges accessing professional services (e.g. housing and health services) within Newham during the pandemic. More deprived areas of England tend to experience poorer quality National Health Service (NHS) care, such as fewer doctors per head [58]. It is therefore likely that this pressure was exacerbated during the pandemic, when the healthcare system was in particularly high demand. This may mean that those who are most vulnerable were not able to access the support they needed. Feelings of lack of support may also be impacted by language barriers [35].

5 Limitations

This qualitative study provided a rich account of the experiences of families from diverse economic backgrounds during the COVID-19 pandemic, but there were some limitations. Although the sample size includes individuals from varying household income levels and ethnic backgrounds, the sample size limited comparisons across ethnic groups due to small subgroup sample sizes. Differences in experiences across ethnicity may therefore have been missed. Further, there were only two males in the sample, meaning that understanding of father’s experiences may be limited.

6 Conclusion and implications

The resultant ECEC closures, financial and housing strains, and restricted social contact of lockdowns meant families were placed under increased pressure and stress. Parents of under 5 s were universally concerned about the impact of lockdowns on children’s social and emotional development and under strain to manage home schooling their children with their work and family commitments. Low-income families were disproportionately disadvantaged in the pandemic, experiencing lack of professional support and community engagement which increased isolation and inadequate housing that restricted children’s space to play. The present research indicates localised learning from those most vulnerable in the pandemic may have universal implications and highlights the importance in involving parents and communities in recovery efforts.

Findings from the present study suggest key areas to focus family support during the recovery phase. Firstly, local authorities need to focus on promoting children’s centres and family engagement with ECEC services and consider how the approach can be tailored to encourage engagement from low-income and vulnerable families. Information should be provided to parents on how to promote social and language development in the home. Further, social and language development should be a focus of ongoing efforts to monitor the impact of the pandemic on young children. The latter could be achieved via data from the Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ) that is administered by health visitors. The need for enhanced social and language support and the implications for future planning and commissioning should also be considered.

Early Years Services Strategies should consider the impact of the pandemic on school readiness, especially for certain cohorts of children, such as those from low-income households. To support families’ mental health, there are opportunities for joint commissioning of services to ensure a whole systems approach. For example, post-natal provision (e.g. mother and baby groups) could be expanded to support and promote maternal mental health, particularly for those who had a baby during the pandemic.

Finally, research has highlighted an acute need to invest in community services and outdoor space. Families require access to high quality outside play amenities, especially in areas where there is a high concentration of homes with little to no garden space. This could include the provision of more play streets. Raising awareness and improving accessibility of community support services should be a focus, especially for services targeting those of lower income. Family friendly initiatives should be developed to encourage access from those with childcare commitments. Finally, location-based initiatives to bring communities together and reduce feelings of loneliness are needed.

Data availability

Data is not currently openly available. Data sharing requests will be considered by the research team.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Rudolph CW, Zacher H. Family demands and satisfaction with family life during the COVID-19 pandemic. Couple Fam Psychol. 2021;10(4):249–59.

Prime H, Wade M, Browne DT. Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am Psychol. 2020;75(5):631–43.

Rosenthal DM, Ucci M, Heys M, et al. Impacts of COVID-19 on vulnerable children in temporary accommodation in the UK. Lancet. 2020;5(5):e241–2.

Brodeur A, Gray DM, Islam A, et al. A literature review of the economics of COVID-19. J Econ Surv. 2020;35:1007–44.

Brewer M, Gardiner L. The initial impact of COVID-19 and policy responses on household incomes. Oxf Rev Econ Policy. 2020;36:S187–99.

Daks JS, Peltz JS, Rogge RD. Psychological flexibility and inflexibility as sources of resiliency and risk during a pandemic: modeling the cascade of COVID-19 stress on family systems with a contextual behavioral science lens. J Contextual Behav Sci. 2020;18:16–27.

Roskos K, Christie J. Examining the play-literacy interface: a critical review and future directions. J Early Child Lit. 2001;1(1):59–89.

McLeish J, Redshaw M. Mothers’ accounts of the impact on emotional wellbeing of organised peer support in pregnancy and early parenthood: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):28.

Best Beginnings. Babies in Lockdown: listening to parents to build back better. 2020.

Brazendale K, Beets MW, Weaver RG, et al. Understanding differences between summer vs. school obesogenic behaviors of children: The structured days hypothesis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity. 2017;14:100.

Fegert JM, Vitiello B, Plener PL, et al. Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: a narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2020;14:20.

Marmot M, Allen J, Goldblatt P, et al. Build back fairer: the COVID-19 marmot review. The pandemic, socioeconomic and health inequalities in England. 2020.

Jiao WY, Wang LN, Liu J, et al. Behavioral and emotional disorders in children during the COVID-19 epidemic. J Pediatr. 2020;221:264-6.e1.

Lee J. Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(6):421.

Liu JJ, Bao Y, Huang X, et al. Mental health considerations for children quarantined because of COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(5):347–9.

Costa P, Cruz AC, Alves A, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on young children and their caregivers. Child. 2022;48(6):1001–7.

Chaabane S, Chaabna K, Bhagat S, et al. Perceived stress, stressors, and coping strategies among nursing students in the Middle East and North Africa: an overview of systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):136.

Read K, Gaffney G, Chen A, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on families’ home literacy practices with young children. Early Child Educ J. 2022;50(8):1429–38.

Panda PK, Gupta J, Chowdhury SR, et al. Psychological and behavioral impact of lockdown and quarantine measures for COVID-19 pandemic on children, adolescents and caregivers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Trop Pediatr. 2021;67(1): fmaa122.

Patrick SW, Henkhaus LE, Zickafoose JS, et al. Well-being of parents and children during the covid-19 pandemic: a national survey. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4): e2020016824.

Gayatri M, Irawaty DK. Family resilience during COVID-19 pandemic: a literature review. Fam J. 2022;30(2):132–8.

Browne DT, Wade M, May SS, et al. COVID-19 disruption gets inside the family: a two-month multilevel study of family stress during the pandemic. Dev Psychol. 2021;57(10):1681–92.

Singletary B, Justice L, Baker SC, et al. Parent time investments in their children’s learning during a policy-mandated shutdown: parent, child, and household influences. Early Child Res Q. 2022;60:250–61.

Foley S, Badinlou F, Brocki KC, et al. Family function and child adjustment difficulties in the COVID-19 pandemic: an international study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(21):11136.

Browne DT, Plamondon A, Prime H, et al. Cumulative risk and developmental health: an argument for the importance of a family-wide science. WIREs Cognit Sci. 2015;6:397–407.

Li J, Bünning M, Kaiser T, et al. Who suffered most? Parental stress and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. J Fam Res. 2022;34(1):281–309.

Conger RD, Elder GH Jr. Families in troubles times: adapting to change in rural America. Hawthorne: Aldine de Gruyter; 1994.

Pailhé A, Panico L, Solaz A. Children’s well-being and intra-household family relationships during the first COVID-19 lockdown in France. J Fam Res. 2022;34(1):249–80.

El Tantawi M, Folayan MO, Aly NM, et al. COVID-19, economic problems, and family relationships in eight Middle East and North African countries. Fam Relat. 2022;71(3):865–75.

Van Lancker W, Parolin Z. COVID-19, school closures, and child poverty: a social crisis in the making. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(5):e243–4.

Adams-Prassl A, Boneva T, Golin M, et al. Inequality in the impact of the coronavirus shock: evidence from real time surveys. J Public Econ. 2020;189:104245.

Andrew A, Cattan S, Costa Dias M, et al. Inequalities in children’s experiences of home learning during the COVID-19 lockdown in England. Fisc Stud. 2020;41(3):653–83.

Kalil A, Mayer, Susan.,Shah, Rohen. Impact of the COVID-19 crisis on family dynamics in economically vulnerable households. In: Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper No 2020-139. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3705592.

Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Non-decent housing and overcrowding. 2021. https://www.jrf.org.uk/data/non-decent-housing-and-overcrowding. Accessed 06 Oct 2023.

Solheim CA, Ballard J, Fatiha N, et al. Immigrant family financial and relationship stress from the COVID-19 pandemic. J Fam Econ Issues. 2022;43(2):282–95.

Trust for London. Poverty and inequality data for Newham. 2020. https://www.trustforlondon.org.uk/data/boroughs/newham-poverty-and-inequality-indicators/. Accessed 15 Aug 2022.

Greater London Authority. Ethnic group population projections. 2020. https://data.london.gov.uk/dataset/ethnic-group-population-projections#:~:text=The%20ethnic%20group%20projections%20are,with%20the%20housing%2Dled%20projection. Accessed 15 Aug 2022.

Aston-Mansfield. Newham: Key Statistics. A detailed profile of key statistics about Newham by Aston-Mansfield’s Community Involvement Unit; 2017.

Patel JA, Nielsen FBH, Badiani AA, et al. Poverty, inequality and COVID-19: the forgotten vulnerable. Public Health. 2020;183:110–1.

Wright J, Hayward A, West J, et al. ActEarly: a City Collaboratory approach to early promotion of good health and wellbeing [version 1; peer review: 2 approved]. Wellcome Open Res. 2019;4:156.

Cameron C, Hauari H, Hollingworth K, et al. Interim briefing report. The first 500: the impact of Covid-19 on families, children aged 0–4 and pregnant women in Tower Hamlets. 2021.

Blundell R, Costa Dias M, Joyce R, et al. COVID-19 and Inequalities. Fisc Stud. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/475-5890.12232.

Cameron C, Hauari H, Heys M, et al. A tale of two cities in London’s East End: impacts of COVID-19 on low- and high-income families with young children and pregnant women. In: Garthwaite K, Patrick R, Power M, Tarrant A, Warnock R, editors., et al., COVID-19 collaborations. Bristol: Policy Press; 2022. p. 88–105.

INVOLVE. Policy on payment of fees and expenses for members of the public actively involved with INVOLVE. INVOLVE. 2016. https://www.invo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/INVOLVE-internal-payment-policy-2016-final-1.pdf. Accessed 06 Oct 2023.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101.

Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. Milton Park: Routledge; 1994.

Bowyer-Crane C, Bonetti S, Compton S, et al. The impact of Covid-19 on school starters: interim briefing 1—parent and school concerns about children starting school. Education Endowment Foundation. Contract No.: 27/04. 2021.

Brown SM, Doom J, Lechuga-Peña S, et al. Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;110:104699.

Ofsted. COVID-19 series: briefing on early years, November 2020. 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-series-briefing-on-early-years-november-2020. Accessed 25 Jan 2024.

Thorell LB, Skoglund C, de la Peña AG, et al. Parental experiences of homeschooling during the COVID-19 pandemic: differences between seven European countries and between children with and without mental health conditions. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01706-1.

National Housing Federation. Housing issues during lockdown: health, space and overcrowding. 2020. https://www.housing.org.uk/globalassets/files/homes-at-the-heart/housing-issues-during-lockdown---health-space-and-overcrowding.pdf. Accessed 25 Jan 2024.

Ponnet K. Financial stress, parent functioning and adolescent problem behavior: an actor-partner interdependence approach to family stress processes in low-, middle-, and high-income families. J Youth Adolesc. 2014;43:1752–69.

Borkowska M, Laurence J. Coming together or coming apart? Changes in social cohesion during the Covid-19 pandemic in England. Eur Soc. 2021;23(sup1):S618–36.

World Health Organisation. The World Health Report 2005: Make every mother and child count. 2005.

Bloomfield L, Kendall S, Applin L, et al. A qualitative study exploring the experiences and views of mothers, health visitors and family support centre workers on the challenges and difficulties of parenting. Health Soc Care Community. 2005;13(1):46–55.

Wang H-H, Wu S-Z, Liu Y-Y. Association between social support and health outcomes: a meta-analysis. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2003;19(7):345–50.

Berkman LF. Assessing the physical health effects of social networks and social support. Annu Rev Public Health. 1984;5:413–32.

Nuffield Trust. How have inequalities in the quality of care changed over the last 10 years?: The Health Foundation; 2020. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/public/files/2020-01/quality_inequality/v2/#Introduction. Accessed 06 Oct 2023.

Funding

This research was funded by the Newham Local Authority. Emma Wilson and Michelle Heys were supported by the NIHR Great Ormond Street Hospital Biomedical Research Centre. This research was based on the Families in Tower Hamlets project that was funded by UKRI-ESRC ES/V004891/1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Eliana Mann (conception of design, acquisition and analysis of data, draft and revision of manuscript), Emma Wilson (conception of design, analysis of data, revision and approval of manuscript), Michelle Heys (conception of design, interpretation of data, revision and approval of manuscript), Claire Cameron (conception of design, interpretation of data, revision and approval of manuscript), Diana Margot Rosenthal (revision of manuscript), Lydia Whitaker (conception of design, revision of manuscript), Hanan Hauari (conception of design, interpretation of data, revision of manuscript), Katie Hollingworth (conception of design, interpretation of data, revision of manuscript), Sarah E. O’Toole (drafting and revision of manuscript).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

No competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mann, E., Wilson, E., Heys, M. et al. A qualitative exploration of the impact of COVID-19 on families with a child under 5 years-old in the borough of Newham, East London. Discov Soc Sci Health 4, 28 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44155-024-00082-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44155-024-00082-4