Abstract

Background

Drug and substance abuse has adverse health effects and a substantial economic burden to the global economies and at the household level. There is, however, limited data on socio-economic disparities in the update of the substance of abuse in low-to-middle income countries such as Kenya. This study aimed to assess the socio-economic disparities among drugs and substances in Murang’a county of central Kenya.

Method

The study design was cross-sectional, and data collection was conducted between November and December 2017. A total of 449 households with at least one person who has experienced substance abuse were sampled from four purposively selected sub-locations of Murang’ a County. Household heads answered questions on house characteristics and as an abuser or on behalf of abusers in their households. Structured questionnaires were used to collect data on types of drugs used, economic burden, and gender roles at the household level. Household socio-economic status (SES) was established (low, middle, and high SES) using principal component analysis (PCA) from a set of household assets and characteristics. Bivariable logistic regression analysis was used to assess the association between SES, gender, and other factors on the uptake of drugs and substance abuse.

Results

Individuals in higher SES were more likely to use cigarettes (OR = 2.13; 95%CI = 1.25–3.61, p = 0.005) or piped tobacco (OR = 11.37; 95% CI, 2.55–50.8; p-value = 0.001) than those in low SES. The wealthier individuals were less likely to use legal alcohol (OR = 0.39; 95%CI = 0.21–0.71, p = 0.002) than the poorest individuals. The use of prescription drugs did not vary with SES. A comparison of the median amount of money spent on acquiring drugs showed that richer individuals spent a significantly lower amount than the poorest individuals (USD 9.71 vs. Ksh 14.56, p = 0.031). Deaths related to drugs and substance abuse were more likely to occur in middle SES than amongst the poorest households (OR = 2.96; 95%CI = 1.03–8.45, p = 0.042).

Conclusion

Socioeconomic disparities exist in the use of drugs and substance abuse. Low-income individuals are at a higher risk of abuse, expenditures and even death. Strategies to reduce drugs and substance abuse must address socio-economic disparities through targeted approaches to individuals in low-income groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Background

The excessive use of alcohol, drugs, prescription medicine, or even other substances leading to significant distress or impairment is termed as drug and substance abuse [1]. Drug and substance abuse has a substantial economic burden globally [2]. Individuals' socioeconomic status is associated with the use of drugs and substances of abuse [3]. The cost of alcohol consumption is above one percent of gross national income (GNI) in both middle and low-income countries globally [4]. The worldwide economic burden of alcohol as per 2002 reviewed studies suggested a range of costs between 210 to 665 billion US dollars [5].

In Kenya, the prevalence of alcohol use among individuals aged 15–65 years was 12.2% in 2017 [6]. Data across three age categories showed that 0.9% of participants aged 10 to 19 years, 5.6% of study participants aged 15–24 years, and 15.1% of those aged 25–35 years were using alcohol. This revealed a decline from 14.2% in 2007 and 13.6% in 2012. The leading regions in terms of the prevalence of alcohol use were Nairobi (17.5%), Eastern (14.3%), and Western (13.4%) [6]. The prevalence of tobacco usage had reduced from 9% in 2012 to about 8.2% in 2017. Khat/ miraa prevalence of use among persons aged 15–65 years stood at 4.1% in 2017. Bhang was found to be the commonly abused narcotic drug in Kenya. Its prevalence among respondents of age 15–65 years maintained at 1% from 2007 to 2017. The Coast region, Nyanza, and Nairobi were on the lead in terms of bhang usage. The usage of at least one drug among those aged 15–65 years has been reducing from 19.9% in 2012 to 18% in 2017 [6].

Although alcohol is the major abused substance in Kenya, other abused substances include tobacco, cannabis, cocaine, amphetamines/khat, and sedatives [7]. Those who chew Khat spend most of their time chewing than engaging in economic activity, negatively affecting the economic development of countries as the production level tends to be low [8]. In Africa, the youths who constitute 40–50% of the population are the biggest abusers of drugs and substances, thus causing a gradual reduction of the workforce, negatively impacting productivity, health deterioration and even death [9, 10].

Kenya is experiencing an increasing problem of drug and substance abuse, with several studies carried out in the nation showing that at any one point in time, every young Kenyan consumes drugs especially, cigarettes and beer [11]. The attempts of achieving urbanization and industrialization of developing countries have been faced by drawbacks from drugs and substance abuse and, as a result, low economic growth, and Kenya is one of the developing countries facing these challenges [12]. The exploitation of drugs and substances of abuse mostly by the youths drains the country’s economy as controlling the demand and supply proves to be expensive and is also a significant impediment to the country’s growth as productivity of the youths become reduced [12].

The utilization of substances of abuse has had an indirect impact on the socio-economic status of the users and their families. Physical disabilities, diseases, and injuries caused by accidents are among the possible health-related effects of substance abuse [13]. Persons involved in alcohol and other drug abuse have a higher risk of death through homicide, suicide, illnesses or accidents [14]. This may result in increased dependency in children when parents or guardians die. Interventions, arrests and adjudication by the juvenile justice systems may be consequences of engaging in drug use. Substance abuse is correlated with violent income-generating behaviours done by the youth [15]. Demand for criminal justice services increases the burden on the resources needed.

Most strikes in Kenya that end up with schools being burnt are attributed to drug use, and this deters economic development as money that would have been used for other projects is invested in rebuilding the schools [12]. A report by united nations office on drugs and crime revealed social consequences of illicit drug abuse and trafficking negatively affect health of individuals the development of countries [16].

A study conducted in Murang’a county to establish student perception of drugs abuse found that drug abuse is associated with school dropout and thus lowering education level and in turn deterring innovations and therefore preventing the development of the economy as students fail to reach productive working-level [17]. A study conducted in Kangema sub-county in Murang’ a county reported that parents’ alcoholism gets to the extent of failing to pay school fees, and hence students drop out of school, which eventually leads to criminal activities thus hindering economic development [17, 18].

There are limited studies on the socioeconomic impact of drugs and substance abuse in Kenya. This analysis focuses on socio-economic disparities in drugs and substance abuse in Murang’ a county, in Central Kenya.

2 Methods

2.1 Study design and population

This was a cross-sectional survey of households with at least one person who had experienced the use of drugs or substances of abuse within 12 months before the survey. The household heads responded to the questions on behalf of their households. The survey purposively selected the Kiharu sub-county based on its high burden of drugs and substance abuse as reported by the National Authority for the Campaign against Alcohol and Drug Abuse (NACADA)[6].

2.2 Study site

The survey was conducted in Murang' a County. It is one of the five counties in the Central Region of the Republic of Kenya. It is bordered to the North by Nyeri, to the South by Kiambu, to the West by Nyandarua and to the East by Kirinyaga, Embu and Machakos counties. Murang’a County is one of the most densely populated counties in Kenya and has one of the high cases of drug and substance abuse in Kenya [6].

2.3 Sample size and sampling

Systematic random sampling was used to sample 449 households from the four sub-locations of Kiharu sub-county, including Karuri (n = 109), Gikandu (n = 114), Gakuyu (n = 114), and Kambirwa (n = 112). Within the community, which were both urban and rural, we systematically sampled households at intervals of about 200 m from a randomly selected landmark, which was either a school or a church. The identified school or church determined our starting point. The direction was determined by spinning a pen in the air and letting it drop on the ground. This method helped ensure that each of the four sub-locations was covered [6].In each house visited the interviewers asked if the household had a person who had experienced drug or substance abuse 12 months before the survey. If an eligible respondent was not found in the visited house, a snowballing approach was used to find the next available respondent within the neighbourhoods.

2.4 Sample size

The sample size was determined using the formula described by Fischer et al. 1998 (27) using the proportion of households with a least a person who has abused drug or substance of abuse, a margin error of 5 and 15% non-response rates

where n was the required sample size, z is the score for a 5% type 1 error for a normal distribution (Z = 1.96), p is the prevalence of drug abusers among the households (Assumed to be 50%), q = 1-p (50%) and e is the margin of error set at 5%. The minimum sample size was 384 per county. An additional 15% non-response rate was added to raise the sample size to 444 per County. The choice of 50% prevalence is to achieve a maximum sample size for an array of different types of the substance of abuse indicators.

2.5 Data collection

Quantitative data were collected using a user-friendly structured questionnaire developed using Open Data Kit (ODK), which prevented data entry errors via data quality checks, which are in-built and deployed into tablets. The study adopted questions from a validated tool known as the Drug Abuse Treatment Cost Analysis Programme (DATCAP) used in health economics to estimate the overall cost of drug abuse and treatment [19]. It is a cost data collection tool and an interview guide that has been designed to be utilized in various social services and medical treatment settings. DATCAP is aimed at collecting and organizing key information on used resources in service delivery. The instrument also captures information on client case flows and program revenues [20]. The DATCAP approach has principles that focus on economic cost, treatment programs, cost estimation, and resource availability, which were analyzed in this study. In LMIC, few studies have used DATCAP, hence, its applicability here was necessary. Participating household heads were approached by the study teams and informed consent was obtained for participants at least 18 years of age. Only households with at least one drug or substance abuser were selected to ensure enough data was captured. The interviews were conducted at the household level, where confidentially and privacy were assured. The interview was administered to the head of the house who provided information about the household characteristics and answered questions on patterns, cost and care-seeking behaviours of the abuser including himself/herself if they were the abusers. Only one interview was conducted per house. Before data collection, the research assistants underwent four days of training, followed by piloting for the reliability of the data collection tools.

2.6 Study tools

The questionnaire was divided into two parts, part one for the head of the household and part two for the substance abuser. The questions included household characteristics, socio-economic indicators such as ownership of assets, household characteristics, cooking fuel, source of water, types of drug or substances abused, patterns of illness and risk of death, expenditure patterns on care-seeking and treatment. To determine whether or not the household was to be included in the study, a question was asked: “Does any member of your household currently or in the previous 12 months abuse (d) any drugs and or substances (cigarettes, legal alcohol, piped tobacco, and prescription drugs)?” Other variables included care given during injury or if there was a case of reported deaths and the amount of money spent to acquire drugs or substances of abuse. Data on socio-demographic variables, age group, marital status, education, occupation, and religion was also collected for the head of the household.

2.7 Data management and statistical analysis

Raw data were first downloaded from the ODK cloud server in CSV file format before being exported to Stata version 15 (College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. StataCorp) for management. The cleaning codes were developed to identify missing data, inconsistent information, and the recording of variables. Missing data were excluded from the analysis.

Chi-square was computed to measure the association between socio-demographic characteristics and wealth tertiles. Where the cell counts were less than five, Fisher's exact test was computed instead of chi-square. A bivariable logistic regression model was used to examine the association between drugs and drug-related illness treatment with socioeconomic status. All the variables with a p-value of less than 0.05 were considered significant. The socio-demographic variables included in the chi-square and Fisher's exact test for cell counts less than five were age group, marital status, education, occupation, and religion. Age group was categorized into 6 groups (Less than 18 years,18–29,30–44,45–59,60–75 and above 75). Level of education was recorded into six categories (never been to school, attended primary school but did not complete, completed primary school level, attended secondary school but did not complete, completed secondary school level and College/University).

Socio-economic status was measured using durable assets and household characteristics such as; Household ownership (the owner of house dwelling and goods) and amenities (materials used for the construction of the dwelling, water source, source of lighting fuel, and cooking fuel) were used as a measure of household status socio-economically [21]. The standardized weight scores were generated using the principal component analysis (PCA) model. PCA is an econometric regression model that generated factor weights from each input indicator of social-economic status [22]. The indicators scores then generate a household score. The higher the score the higher the household SES and vice versa. Weight scores were ranked to get the wealth tertiles (low, middle, high) [21]. The households in the low wealth tertiles were those with less household ownership assets and amenities while households in the high wealth tertiles were those with more household ownership assets and amenities. The three socioeconomic status categories (Low, Middle, and high) divided the data into three equal groups, with approximately 33.3% of the observations falling into each category. SES was the main independent variable in this analysis. Kruskal–Wallis test was used to test the null hypothesis of equality of medians within the wealth quintile groups for skewed data and an independent sample t-test was used for normally distributed data to compare mean estimates. The costs were estimated using the currency conversion rate of 1US dollars equivalence to 103 Kenya shillings, the average for 2017.

3 Results

3.1 Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants

A total of 449 household heads were interviewed and of these 365 (81.3%) were abusers and 84(18.7%) had not abused drugs 12 months before the survey. Of those respondents interviewed, 28.5% (n = 128) were of age 30–44 years, and 28.1% (n = 126) were 45–59 years. More than 60% of those who responded had at least completed primary level schooling. About 30.9% of the low income, 8% of the middle-income, and 20% of the high-income household heads had never married (Table 1). Two participants aged 16 and 17 years were included (considered as mature minors) because they already had families of their own.

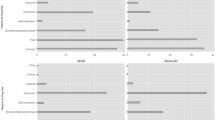

3.2 Association between household socio-economic status and types of drugs or substances abused

The results show Table 2 shows the odds of using a type of drug by household socio-economic status. Using the low SES as the comparator, individuals in middle SES were less likely to take legal alcohol (OR = 0.45; 95% CI, 0.25–0.78; p-value = 0.005). However, those individuals in the middle SES (OR = 5.41; 95% CI, 1.14–25.67; p-value = 0.033) or high SES (OR11.37;95%CI = 2.55–50.8,p = 0.001) were more likely to use piped tobacco than those in lower SES. Those in high SES were more likely to abuse cigarettes (OR = 2.13; 95% CI, 1.25–3.61; p-value = 0.005) but less likely to abuse legal alcohol (OR = 0.39; 95% CI, 0.21–0.71; p-value = 0.002). (Table 2).

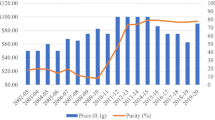

3.3 Mean amount of money spent by individuals to acquire drugs in one month by household socio-economic status

Table 3 shows the comparison of the mean and median amount of money spent on drugs by households per SES in one month. Low-income households (n = 129) spent a median of USD 14.56(Inter-quantile range IQR (USD 4.85–34.95) compared to high-income households (n = 115), who spent a median of USD 9.71 (IQR USD2.91 to 19.42). The difference was statistically significant (p = 0.0310) (Table 3).

3.4 Pairwise comparison of the mean amount of money spent by household to acquire drugs in one month by SES

A posthoc Dunn’s test [23] was performed in Stata to assess if there was a significant difference in mean expenditure between the wealth quintile categories. The results show that the difference in the amount spent to acquire drugs was significantly higher amongst the low SES (USD 25.85; 95%CI = [20.12–31.85] than amongst the high SES (USD 18.84; 95%CI = [14.21–23.46], t-test p-value = 0.044). There was no significant difference between the high and the middle-income level in expenditures to acquire drugs and substances of abuse (p-value = 0.999) (Table 4). Results in Table 4 compares the differences in the mean amount of expenditures to acquire drugs between socioeconomic groups.

3.5 Association between drug-related illness treatments of individuals heads who experienced substance abuse by wealth quintile

Table 5 shows the drug-related illness treatment of individuals by wealth quintile. Households in the middle SES were significantly more likely to experience death as a result of drug-related illness than those in the low SES (OR = 2.96; 95% CI, 1.03–8.45; p-value = 0.042). There was no difference between wealth quintiles in terms of the proportion of those treated for an illness, admitted for drug illness, and the probability of providing care.

4 Discussion

This study has established that burden of use of drug and substance abuse is significantly higher amongst low than higher-income level individuals. Individuals from low-income households spent a significantly higher amount of money to purchase drugs and substances of abuse. We had hypothesised that low-income individuals would suffer socio-economic disparities in illness and expenditure due to drugs and substance abuse. From our results, we confirmed our hypothesis, hence rejecting the null hypothesis of no relationship between SES and the burden of drugs and substances of abuse. We further examined the association between household socioeconomic status and usage of four different types of drugs that were often abused. These included; legal alcohol, piped tobacco, cigarettes, and prescription drugs. Similar studies have reported a higher association of uptake of cigarettes and alcohol among those with low socioeconomic status (SES) [24,25,26]. The study established that a household member from the middle quintile was more likely to die of drug-related illness than a household member from the low quintile group.

This study also established that a person in the higher SES was more likely to abuse cigarettes than one in a low-income level. This result was similar to that of a previous study that indicated that adolescents from the highest personal income quintile were more likely to be smoking [27]. The study results, however, contradict a study conducted in India, which indicated that the regular use of alcohol and tobacco had a significant increase with decreasing wealth quintile [28].

The study also established that there was a significant difference in the amount of money spent to acquire drugs between the different wealth quintile groups. The study results indicated that individuals from the low wealth quintile spent the highest amount, followed by the middle wealth quintile and, lastly, the high quintile. Results of a previous study, however, showed that the amount spent to acquire drugs increased with increasing quintile [29]. This could have been the case since most of the poorest people lack jobs and therefore have more time to spend drinking and smoking than the middle and high-income level groups. They, therefore, end up spending a lot of money on drugs and substances. Wealthier individuals were more likely to be admitted for drug-related illnesses than the poor. This could be because more affluent persons can afford the cost of admission to the hospital wards than the poor. These results compared to those of a previous study that indicated a similar trend across the wealth quintile [30].

The study results further showed that those in middle SES were more likely to experience death in the household than those in low SES. This could have been so because having a stronger purchasing power may lead to an increase in the likelihood of spending more money if individuals are addicted to drugs. This could, in effect, increase the risk of death in middle and high income than it would in low-income households.

The reduction of socio-economic disparities is part of several sustainable development goals to achieve universal health coverage [31]. One of the strategies of the Kenya Health Policy 2014–2030 was to improve health indicators through equitable distribution of health services and interventions in line with the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) to achieve universal access to safe, effective, quality and affordable health care services for all [32]. However, the existence of socioeconomic inequalities and disparities is a crucial barrier to achieving international development goals [33].

The reasonably large sample size is a vital strength of this survey to provide estimates that can be generalized to the whole population [34]. However, the data on the economic impact of drugs and substance abuse was taken in a single visit, and hence the burden might have been over-estimated. The findings of this study are only generalizable to this study site only and not nationally, but the methods can be applied nationally. This was a cross-sectional study design that cannot monitor the time effect and has confounding factors not addressed in the analysis, which can be looked into for future research.

5 Conclusions

This survey established a significant association between drugs and substance abuse with household wealth quintile. The low-income level is more affected by expenditures and illnesses than those of high SES. This survey is essential as it shows the economic impact of drugs and substance abuse situations, which can be used in making policies and guiding interventions. There was a significant difference in the amount used to acquire drugs between the three groups of wealth quintile. The low-income level in terms of wealth quintile was found to spend the highest amount of money on drugs and substances of abuse, in which the high-income level spent the least amount of money.

The results from this survey support an urgent requirement to establish new policies and strategies to curb the economic impact of drugs and substances by reducing the amount spent to acquire drugs [35]. The results from this study are also relevant as they highlight the high risk of death of a household member from the middle and high quintile group compared to one in a low quintile. These differences in quintile underscore the requirement for integrated policies and programs that address the middle and high quintile needs for services and information related deaths associated with drugs and substance abuse.

This may be the first survey to dwell on the economic impact of drugs and substance abuse in the County of Murang’a; it, therefore, adds to the existing literature and will help scholars intending to research the economic impact of drugs and substance abuse. The methods used for analysis can be replicated in the future for detailed analysis.

In this study, the implications for policy and practice are the reduction of the knowledge gap by ensuring that research addresses socio-economic disparities more so on the uptake of substance abuse in various regions of the country. Existing drug policies and practices should be mainstreamed. Misuse of prescription drugs should be incorporated in policies and practices. More studies should be conducted to examine the cost-effectiveness of interventions so that they are economically viable and effective. There needs to be the provision of integrated and coordinated services that address issues beyond substance use, which may need embedment of collaboration into strategies and policies.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

STATA version 15 was used for all the analysis.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- IQR:

-

Inter-quantile range

- GNO:

-

Gross National Income

- KEMRI:

-

Kenya Medical Research Institute

- NACADA:

-

National Agency for Campaign against Drug Abuse

- ODK:

-

Open data kit

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic status

- SDGs:

-

Sustainable development goals

References

Wills TA, Vaccaro D, McNamara G. The role of life events, family support, and competence in adolescent substance use: a test of vulnerability and protective factors. Am J Community Psychol. 1992;20:349–74.

Thavorncharoensap M, Teerawattananon Y, Yothasamut J, Lertpitakpong C. The economic impact of alcohol consumption: a systematic review. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2009;4:20.

Moradinazar M, Najafi F, Jalilian F, Pasdar Y, Hamzeh B, Shakiba E, Hajizadeh M, Haghdoost AA, Malekzadeh R, Poustchi H. Prevalence of drug use, alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking and measure of socioeconomic-related inequalities of drug use among Iranian people: findings from a national survey. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2020;15:1–11.

Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, Thavorncharoensap M, Teerawattananon Y, Patra J. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. The lancet. 2009;373:2223–33.

Baumberg B. The global economic burden of alcohol: a review and some suggestions. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2006;25:537–51.

Kamenderi M, Muteti J, Okioma V, Kimani S, Kanana F, Kahiu C. Status of drugs and substance abuse among the general population in Kenya. Afr J of Alcohol & Drug Abuse. 2021;2:54. https://ajada.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Status-of-Drugs-and-Substance-Abuse-in-Kenya-AJADA-Vol-1.pdf.

Ndetei DM, Khasakhala LI, Ongecha-Owuor FA, Kuria MW, Mutiso V, Kokonya DA. Prevalence of substance abuse among patients in general medical facilities in Kenya. Substance Abuse. 2009;30:182–90.

Asuni T, Pela O. Drug abuse in Africa. Bull Narc. 1986;38:55–64.

Odejide A. Status of drug use/abuse in Africa: a review. Int J Ment Heal Addict. 2006;4:87–102.

Obot IS. Substance abuse, health and social welfare in Africa: an analysis of the Nigerian experience. Soc Sci Med. 1990;31:699–704.

Maithya R. Drug abuse in secondary schools in KENYA: developing a programme for prevention and intervention. academia.edu: University of South Africa. 2009. https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/45427540/Dissertation-with-cover-page-v2.pdf?Expires=1648884380&Signature=ctNUAfZ0S0a1lUhLqfTaUQdXaVqXTlnb825952Z4yk0hgKjGs-FrVpMSgoxEZPOZQRPCoFkwAV-khyzLJr8uu0Y22-wbUXMQRp6Xl96L8aHvfxz-p2pIyqR~83rm9K7IeZLtaTLXb~bwou9Fr0amoO8JcOTaEVZza24SNuPkAtHbdCrPmWZJs~nhlaHRpJ-EMjFaE1015Y84W-xiU2OLX7c457i~L0VHd-gWGX2SowzcxTqCEVQy5ijq9Uda13-aBw6vpYgVwH6tw~OR7M9DDKspi63i8Ww2oFsJtU6Q9SRltp-ztLD5xWDnvQFBzepeQY4zUBlgPfpZl~LxRjbW4g__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA.

Walt LC, Kinoti E, Jason LA. Industrialization stresses, alcohol abuse & substance dependence: differential gender effects in a Kenyan rural farming community. Int J Ment Heal Addict. 2013;11:369–80.

Smith MF, Hiller HC. influence of drug abuse on human health in United States of America. Afr J Emerg Issues. 2021;3:16–28.

Bonkat-Jonathan L. Tongs LA. Rising drug use and youths in Nigeria: a need for an urgent legislative action. 2021. https://ir.nilds.gov.ng/bitstream/handle/123456789/435/Rising%20Drug%20Use%20and%20Youths%20in%20Nigeria.pdf.

Bougart NB. Risks, protective factors and intervention strategies for youth substance abuse. Servamus. 2019;112:52–3.

UNODC: Economic and social consequences of drug abuse and illicit trafficking. In: United Nations. 1998;64. https://www.unodc.org/pdf/technical_series_1998-01-01_1.pdf.

Kyalo PM, Mbugua R. Narcotic Drug Problems in Murang’a South District of Kenya: A Case Study of Drug Abuse by Students in Secondary Schools. Africa Journal of Social Sciences. 2011;1:73–83.

Wachira CW. Effect of parental alcoholism on students’ education in public secondary schools: a case of Kangema Sub-county, Murang’a, Kenya. Kenya: KeMU; 2017.

French MT. Drug abuse treatment cost analysis program (DATCAP): User’s manual. Florida: University of Miami; 2003.

French MT, Dunlap LJ, Zarkin GA, McGeary KA, McLellan AT. A structured instrument for estimating the economic cost of drug abuse treatment: The Drug Abuse Treatment Cost Analysis Program (DATCAP). J Subst Abuse Treat. 1997;14:445–55.

Vyas S, Kumaranayake L. Constructing socio-economic status indices: how to use principal components analysis. Health Policy Plan. 2006;21:459–68.

Were V, Buff AM, Desai M, Kariuki S, Samuels A, Ter Kuile FO, Phillips-Howard PA, Kachur SP, Niessen L. Socioeconomic health inequality in malaria indicators in rural western Kenya: evidence from a household malaria survey on the burden and care-seeking behaviour. Malar J. 2018;17:1–10.

Pereira DG, Afonso A, Medeiros FM. Overview of Friedman’s test and post-hoc analysis. Commun Stat Simul Comput. 2015;44:2636–53.

Harwood GA, Salsberry P, Ferketich AK, Wewers ME. Cigarette smoking, socioeconomic status, and psychosocial factors: examining a conceptual framework. Public Health Nurs. 2007;24:361–71.

Hiscock R, Bauld L, Amos A, Fidler JA, Munafò M. Socioeconomic status and smoking: a review. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1248:107–23.

Charitonidi E, Studer J, Gaume J, Gmel G, Daeppen J-B, Bertholet N. Socioeconomic status and substance use among Swiss young men: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:1–11.

Perelman J, Alves J, Pfoertner TK, Moor I, Federico B, Kuipers MA, Richter M, Rimpela A, Kunst AE, Lorant V. The association between personal income and smoking among adolescents: a study in six European cities. Addiction. 2017;112:2248–56.

Neufeld K, Peters D, Rani M, Bonu S, Brooner R. Regular use of alcohol and tobacco in India and its association with age, gender, and poverty. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77:283–91.

Holmes J, Meng Y, Meier PS, Brennan A, Angus C, Campbell-Burton A, Guo Y, Hill-McManus D, Purshouse RC. Effects of minimum unit pricing for alcohol on different income and socioeconomic groups: a modelling study. Lancet. 2014;383:1655–64.

Worrall E, Basu S, Hanson K. The relationship between socio-economic status and malaria: a review of the literature. London: Background paper for Ensuring that malaria control interventions reach the poor; 2002. p. 56.

Hosseinpoor AR, Victora CG, Bergen N, Barros AJ, Boerma T. Towards universal health coverage: the role of within-country wealth-related inequality in 28 countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:881–9.

Kenya MoH. Kenya health policy 2014–2030. Nairobi: MoH; 2014.

Niessen LW, Mohan D, Akuoku JK, Mirelman AJ, Ahmed S, Koehlmoos TP, Trujillo A, Khan J, Peters DH. Tackling socioeconomic inequalities and non-communicable diseases in low-income and middle-income countries under the Sustainable Development agenda. Lancet. 2018;391:2036–46.

Maxwell SE, Kelley K, Rausch JR. Sample size planning for statistical power and accuracy in parameter estimation. Annu Rev Psychol. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093735.

Goodstadt MS. Prevention strategies for drug abuse. Issues Sci Technol. 1987;3:28–35.

Acknowledgements

The authors are particularly grateful to Murang’a County and Kiharu sub-county Stakeholders for their technical support during the implementation of this study. The members of the study communities are also thanked for their participation and patience during data collection activities. Appreciation is also given to the Murang’a County Hospital Staff as well as the Murang’a County Commissioner for embracing the study and supporting community entry and engagement. This study has been published with the permission of the Director-General, KEMRI.

Funding

This study was funded by KEMRI Funding for Health Research 2015/2016: KEMRI/GRG/15/31. The funders had no role in the design of this study and analyses and interpretation of the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DWN, CO, CM, SA, HK, EE, and VW conceived the study. DWN, CO, CM, and VW contributed to the study design. DWN, CO, CM, SA, HK, and VW coordinated the data collection. VW and CO conducted the data analysis. VW wrote the manuscript, DWN contributed to its refinement, and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was received from the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI), Scientific and Ethics Review Unit (SERU No. 3237), and written informed consent was sought from all the study participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Were, V.O., Okoyo, C.O., Araka, S.B. et al. Socioeconomic disparities in the uptake of substances of abuse: results from a household cross-sectional survey in Murang’ a County, Kenya. Discov Soc Sci Health 2, 5 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44155-022-00008-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44155-022-00008-y