Abstract

Background

Adolescents cannabis users are at a substantially elevated risk for use of highly addictive drugs such as cocaine, heroin, and nonmedical use of prescription drugs. Unknown is whether this elevated risk applies to adolescent cannabis users who have never smoked a combustible cigarette, a group that has grown considerably in size in recent years. This study documents the recent growth in the proportion of adolescent cannabis users who abstain from combustible cigarette use, and examines their probability for use of addictive drugs.

Methods

Data are annual, cross-sectional, nationally-representative Monitoring the Future surveys of 607,932 U.S. 12th grade students from 1976 to 2020.

Results

Among ever cannabis users, the percentage who had never smoked a combustible cigarette grew from 11% in 2000 to 58% in 2020. This group had levels of addictive drug use that were 8% higher than their peers. In comparison, adolescents who had ever used cannabis—regardless of whether they had ever smoked a cigarette—had levels of addictive drug use 500% higher than their peers.

Conclusions

Adolescent cannabis users who have not smoked a combustible cigarette have much lower levels of addictive drug use than the group of cannabis users as a whole. These results suggest policies and laws aimed at reducing adolescent prevalence of addictive drugs may do better to focus on cigarette use of adolescent cannabis users rather than cannabis use per se.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Adolescent cannabis users have a substantially elevated probability for illicit use of highly addictive drugs such as cocaine, heroin, hallucinogens, and nonmedical use of prescription drugs [1,2,3]. This elevated probability is a major concern of parents, teachers, and government, and it is also a cornerstone for theories, legal policies, and prevention strategies in the drug field. For theory, it is the basis for both the “gateway” and “liability” theories, with the former positing that cannabis use causes the elevated probability and the latter positing that individual predisposition for drug use plays a confounding role [2, 4,5,6]. For legal policy, a concern that adolescent cannabis users may progress to use of addictive drugs has long motivated advocacy aimed at keeping cannabis use illegal as a deterrent to adolescent use [7, 8]. And for prevention, the elevated probability suggests cannabis reduction could possibly be an effective target for the goal of reducing use of highly addictive drugs [8, 9].

Largely unexamined is whether this elevated probability is present among adolescent cannabis users who have never smoked a combustible cigarette. Current, major theories in the field provide little guidance on their levels of drug use. Theories of drug progression typically posit cannabis use as an intermediary stage in a sequence that comes after tobacco initiation and before use of highly addictive drugs [2]. Whether cannabis remains as strongly associated with use of addictive drugs when it is out of this sequence and does not accompany tobacco use is unknown. In addition, a pattern of cannabis use without tobacco use does not fit well with “liability” theories that posit a generalized predisposition for drug use in some individuals [6].

When much of the today’s theories and laws on cannabis were first developed in the 1960s and 1970s, it was difficult to examine the elevated probability of illegal drug use for cannabis use net of cigarette smoking. Very high levels of cigarette use among adolescent cannabis users [10] presented methodological and interpretive challenges to disentangling their influence. Furthermore, because cannabis and cigarette use went hand-and-hand, a focus on the small group of adolescent cannabis users who abstained from cigarette smoking seemed more of an academic exercise than it did an opportunity to inform policy and practice.

In recent years adolescent cannabis users who abstain from cigarette smoking now warrant more attention because the size of this group has increased markedly. This increase has roots in the “great decline” in cigarette smoking that has taken place over the past two decades [11]. During this time the percentage of 12th grade students who have ever smoked a cigarette fell from 63% in 2000 to 24% in 2020 [12]. No such decline took place in prevalence of adolescent lifetime cannabis use, which was at 44% in 2020 where it has hovered for the past decade [12]. As a result of these trends a minimum of about half of the 44% who had used cannabis in 2020 had never smoked a cigarette, a conservative estimate assuming all the 24% that had smoked a cigarette had also used cannabis.

Currently unknown and presented in this study are (a) trends in the specific size of the group of cannabis users who have abstained from cigarette use from 1976 to 2020, and (b) their level of use of addictive drugs.

2 Methods

2.1 Study sample

Data come from the annual, nationally-representative Monitoring the Future study [13], which uses self-administered questionnaires in school classrooms to survey U.S. students. The project has been approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board, approval #HUM00131235. Informed consent (active or passive, per school policy) was obtained from parents for students younger than 18 years and from students aged 18 years or older. Independent, nationally-representative samples 12th grade students were surveyed each year since 1976 through 2020. The survey and sampling procedures are described in detail elsewhere [14]. Student response rates for the survey averaged 82%, and non-response was largely due to student absence.

Table 1 lists the text and coding of the study measures. Item-level non-response was low, with 97% of respondents providing information for lifetime cigarette use, 96% for lifetime cannabis use, and 94% for lifetime use of addictive drugs other than cannabis. After listwise deletion 89% of respondents provided information for all three of these substances and the control variables, resulting in a total analysis sample of 607,932 12th grade students.

2.2 Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed in STATA MP 17 and use the “svy:” suite of commands to take into account sample probability weights, as well as clustering of respondents in primary sampling units and strata [14].

Prevalence levels were calculated using proportions. The analysis presents results from multivariable regressions that control for time trends and demographics. To take into account potentially non-linear time trends the study years from 1976 to 2020 are grouped into 5-year intervals, and an indicator for each is included in the multivariable analyses (absent the reference category). Results for the multivariable analyses present relative risk ratios, estimated using a generalized linear model with a binomial distribution for the residuals and a log link function.

3 Results

Figure 1 presents trends in prevalence of lifetime cannabis use and lifetime combustible cigarette use for 12th grade students. In the last decade lifetime cannabis prevalence has changed little and stayed within a narrow range of 43% and 45% from 2010 to 2020 (see Additional file 1: Table S1 for specific estimates and 95% confidence intervals by year).

Note: Additional file 1: Table S1 in appendix presents specific estimates of proportions and 95% confidence intervals for all years. n = 607,932

Percentage lifetime cannabis and cigarette use, by year.

In contrast, Fig. 1 shows that prevalence of lifetime combustible cigarette use has declined dramatically over the study period, especially since the year 2000. It declined almost one half in just 10 years, from 42% in 2010 to 24% in 2020 (see Additional file 1: Table S1 for specific estimates and 95% confidence intervals by year). Taken together, the findings of a near-constant prevalence of lifetime cannabis use and a substantial decline in combustible cigarette use implies a rise in the percentage of cannabis users who have never smoked a combustible cigarette.

Figure 2 presents trends in cigarette abstention among ever cannabis users in 12th grade. In the last decade the percentage of cannabis users who abstained from cigarette use more than doubled, from 27% in 2010 to 58% in 2020 (see Additional file 1: Table S1 for specific estimates and 95% confidence intervals by year). This increase started in 2000 when prevalence of cigarette abstention among cannabis users was 11%; in 2000 and the years beforehand abstention from cigarette smoking among ever cannabis users was uncommon and hovered between 8 and 12%.

Note: Additional file 1: Table S1 in appendix presents specific estimates of proportions and 95% confidence intervals for all years. n = 292,845

Percentage no lifetime cigarette use among ever cannabis users.

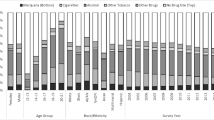

Table 2 presents lifetime cannabis use without combustible cigarette use as a predictor of addictive drug use, as measured by an index that includes any use of heroin, hallucinogens, cocaine, or nonmedical use of prescription drugs. Model 1 of Table 2 shows that students who had used cannabis and never smoked a cigarette had levels of addictive drug use 8% higher than the other students (RR = 1.08; 95% CI 1.06–1.11). This estimate is the overall, increased risk for all years combined.

Model 2 of Table 2 takes into account possible variation across time periods in the heightened levels of addictive drug use for cannabis users who have never smoked a cigarette in comparison to their peers. In this model the coefficient for lifetime cannabis use without cigarette use refers to the referent time period of 2015–2020. The relative risk estimate of 1.17 (95% CI 1.11–1.24) indicates that these students were 17% more likely to have used an illegal drug in their lifetime than the other students during these years. Additional file 1: Table S2 presents for all reference time periods the coefficient of lifetime cannabis use without cigarette use. The relative risk varies from 0.97 to 1.30, and for five time periods it is not statistically significant (in 1976–79, 1995–99, 2000–04, 2005–09 and 2010–14).

Model 3 of Table 2 adds to model 2 the demographic controls of parental education, sex, and race/ethnicity. The inclusion of these controls resulted in little change in the coefficient for lifetime cannabis use without cigarette use. The relative risk increased slightly from 1.17 to 1.21 for the reference time period of 2015–2020. Across all five-year time blocks this relative risk ranged from 1.02 to 1.40, and for four time periods was not statistically significant (Additional file 1: Table S2).

Models 1 through 3 of Table 3 present results for lifetime cannabis use, regardless of cigarette use history, as a predictor of addictive drug use. Model 1 shows that students who had used cannabis had levels of addictive drug use five times higher than the other students (RR = 5.03; 95% CI 4.95–5.11) for all years combined. Model 2 take into account possible variation across time periods in this relative risk, and indicates a value of 5.72 (95% CI 5.43–6.02) for the reference period of 2015–2020. Additional file 1: Table S2 presents for all reference time periods the relative risks for lifetime cannabis use as predictor of illegal drug use, and they vary between 4.56 and 5.81 and are all statistically significant.

Model 3 of Table 3 adds to model 2 the demographic controls of parental education, sex, and race/ethnicity. The inclusion of these controls resulted in little change in the coefficient for lifetime cannabis use as a predictor of lifetime illegal drug use. The relative risk decreased slightly from 5.72 to 5.70 for the referent time period of 2015–2020. Across all five-year time blocks these relative risks ranged from 4.51 to 5.80 (Additional file 1: Table S2).

4 Discussion

This study contributes two novel findings to the field. First, we find that the risk for use of highly addictive drugs differed little for adolescent cannabis users who have never smoked a combustible cigarette in comparison to their peers. These adolescents had an elevated probability to use addictive drugs that was typically 20% or less in comparison to their peers, a finding that was similar over all time periods in the 45 years of the survey. In many years the risk was substantially smaller and not statistically significant. This finding contrasts with adolescent cannabis users as a whole—regardless of whether they had ever smoked a combustible cigarette—who as a group had a fivefold higher probability of using addictive drugs in comparison to their peers.

A second contribution of this study is that it documents a substantial increase in the proportion of adolescent cannabis users who abstained from using combustible cigarettes. In 2020 58% of all adolescent cannabis users had never smoked a combustible cigarette, which is one percentage point shy of the all time high of 59% set the previous year. This proportion has grown gradually and steadily since the year 2000 when it was 11%; up to that point the proportion had changed little and had hovered at around 10% since at least 1976.

In terms of policy and practice these results suggest that targeting cigarette use may be a promising strategy to reduce addictive drug use among adolescent cannabis users. A host of policies and programs with proven efficacy to reduce adolescent cigarette use were employed to achieve the “great decline” [11] in adolescent cigarette use since 2000. These policies and programs were set in place by the Master Tobacco Settlement Agreement of 1998 [15] and include restrictions on cigarette advertising, sponsorship, and lobbying activities targeting youth; increased cigarette prices for consumers through taxes and other means; support for a National Public Education Foundation to create nationwide media and education campaigns to reduce youth smoking and to conduct related research (since renamed the “Truth Initiative”); and substantial payments to the U.S. states to aid their implementation of additional, state-specific anti-smoking programs. The substantial decline in adolescent cigarette smoking since 1998 speaks to the success of these programs. Ideally, if adolescent combustible cigarette use could be reduced to zero, then the results of this study suggest that all adolescent cannabis users could have little to no elevated probability of use for addictive drugs in comparison to their peers.

In terms of legal policy the study results show that a public health approach can potentially address some of the major concerns intended to be addressed by outlawing cannabis use. One rationale for making cannabis use illegal is to reduce use of more addictive drugs by deterring youth from using cannabis and thereby stopping short any associated processes that lead to use of more addictive drugs. The results of this study suggest that the aim of reducing addictive drug use could potentially be addressed by preventing cigarette use among adolescent cannabis users, using the public health approach of tobacco control.

In terms of theory these results point to the rise of an adolescent cannabis user that is not well explained by current, major drug theories in the field. “Gateway” theories apply to cannabis users who first used cigarettes and then progressed to use of highly addictive drugs, neither of which applies to adolescent cannabis users who have never smoked a cigarette. “Liability” theories apply to cannabis users who also use many other substances, which, again, is not a good match with adolescent cannabis users who have never smoked a cigarette. Given that the majority of adolescent cannabis users now abstain from cigarette use, this group warrants detailed attention to identify their motivations to use cannabis, their patterns and frequency of cannabis use, their drug use trajectories, as well as potential intervention points.

In terms of directions for future research, the growing, adolescent use of non-combustible tobacco products, such as e-cigarettes, provides a unique opportunity to consider the mechanisms linking use of marijuana, cigarettes, and addictive drugs. Use of e-cigarettes has surged dramatically since 2017 [16, 17], including some of the largest increases ever recorded in 46 years for use of any substance [18], and in 2021 past 30-day prevalence is 20% in 12th grade, 13% in 10th grade, and 8% in 8th grade [19]. No concomitant population-level increase in adolescent use of additive drugs has taken place during this surge [12]. A comparison of adolescent marijuana users who use combustible cigarettes with those who use e-cigarettes offers a unique opportunity to isolate biological and environmental mechanisms associated with addictive drug use. Such a comparison is particularly strategic because e-cigarettes and combustible cigarettes deliver similar levels of nicotine, and thus the influence of nicotine can cancel out in the comparison [20].

We note two study limitations. First, the study’s cross-sectional research design cannot prove or disprove causation. Consequently, this study centers on associations of cannabis use with use of highly addictive drugs and discusses them in relation to major theories in the field such as the gateway theory, which posits that cannabis causes use of other addictive drugs, and the liability theory, which does not include a role for causality.

Second, the sample does not contain 12th grade students who have dropped out of school. For the purposes of this study we expect that inclusion of dropouts would not change the main study results or substantive conclusions. From 2010 to 2020 levels of high school dropout changed by three percentage points—dropping from 8.7% to 5.7% [15]—and this change is too small to account for the substantial drop in combustible cigarette use among cannabis users documented by this study from 2010 to 2020.

5 Conclusions

These study results indicate only slightly elevated levels of addictive drug use for the group of adolescent cannabis users who have never smoked a combustible cigarette, a group that in recent years has grown to become the majority of adolescent cannabis users. These results suggest policies and laws aimed at reducing adolescent prevalence of addictive drugs may do better to focus on cigarette use of adolescent cannabis users rather than cannabis use per se.

Data availability

All data is publicly accessible at no cost to users at the National Addiction & HIV Data Archive Program (NAHDAP) data repository @ https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/NAHDAP/series/35.

Code availability

All programs run using STATA 17.

References

Yamaguchi K, Kandel DB. Patterns of drug use from adolescence to young adulthood: III Predictors of progression. Am J Public Health. 1984;74(7):673–81.

Kandel DB, editor. Stages and pathways of drug involvement: Examining the Gateway Hypothesis. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2002.

Kandel D, Kandel E. The Gateway Hypothesis of Substance Abuse: Developmental, Biological, and Societal Perspectives. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104(2):130–7.

Kandel D. Stages in adolescent involvement in drug use. Science. 1975;190:912–4.

Kosterman R, Hawkins JD, Guo J, Catalano RF, Abbott RD. The dynamics of alcohol and marijuana initiation: patterns and predictors of first use in adolescence. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(3):360–6.

Vanyukov MM, Tarter RE, Kirillova GP, et al. Common liability to addiction and “gateway hypothesis”: theoretical, empirical and evolutionary perspective. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;123:S3–17.

DuPont RL, Voth EA. Drug legalization, harm reduction, and drug policy. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:461–5.

Kleber HD. Our current approach to drug abuse--progress, problems, proposals. Mass Medical Soc; 1994.

U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. Preventing Marijuana Use among Youth & Young Adults. 2017. https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2018-07/DEA-Marijuana-Prevention-2017-ONLINE.PDF.

Single E, Kandel D, Faust R. Patterns of multiple drug use in high school. J Health Soc Behav. 1974;9:344–57.

Miech R, Keyes KM, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. The great decline in adolescent cigarette smoking since 2000: consequences for drug use among US adolescents. Tob Control. 2020;29(6):638–43.

Miech RA, Johnston L, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2020: Volume I, Secondary School Students. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research; 2021.

Monitoring the Future. Data from: Monitoring the Future (MTF) Public-Use Cross-Sectional Datasets, National Addiction & HIV Archive Program, November 11, 2021. 2021. https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/NAHDAP/series/35.

Bachman JG, Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Miech RA. The Monitoring the Future Project after Four Decades: Design and Procedures. Occasional Paper #82. 2015. http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/occpapers/mtf-occ82.pdf. Accessed November 17, 2019.

Jones WJ, Silvestri GA. The Master Settlement Agreement and its impact on tobacco use 10 years later: lessons for physicians about health policy making. Chest. 2010;137(3):692–700.

Miech RA, Johnston L, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Patrick ME. Trends in Adolescent Vaping from 2017 to 2019 – US National Estimates. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1490–1.

Miech R, Leventhal A, Johnston L, O’Malley PM, Patrick ME, Barrington-Trimis J. Trends in Use and Perceptions of Nicotine Vaping Among US Youth From 2017 to 2020. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;175(2):185–90.

Miech RA, Johnston L, OMalley PM, Bachman JG, Patrick ME. Adolescent Vaping and Nicotine Use in 2017–2018 -- US National Estimates. New England J Med 2018;380:192–3.

Teen Use of Illicit Drugs Decreased in 2021, as the COVID-19 Pandemic Continued [press release]. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan; 2021.

Eaton DL, Alberg AJ, Goniewicz M, et al. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2018.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute of Drug Abuse, part of the U.S. National Institutes of Health, by Grant # R01DA001411 (Principal Investigator Richard Miech).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The sole author Richard Miech conceptualized the paper, performed all data analyses, and wrote the manuscript. The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Human subjects and informed consent

The project has been approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board, approval #HUM00131235. Informed consent (active or passive, per school policy) was obtained from parents for students younger than 18 years and from students aged 18 years or older

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Miech, R.A. Adolescent cannabis users who have never smoked a combustible cigarette: trends and level of addictive drug use from 1976 to 2020. Discov Soc Sci Health 2, 3 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44155-022-00005-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44155-022-00005-1