Abstract

Discourse markers can have various functions depending on the context in which they are used. Taking this into consideration, in this corpus-based research, we analyzed and unveiled quantitatively and qualitatively the functions of four discourse markers in academic spoken English. To this purpose, four discourse markers, i.e., “I mean,” “I think,” “you see,” and “you know,” were selected for the study. The British Academic Spoken English (BASE) corpus was used as the data gathering source. To detect the discourse markers, concordance lines of the corpus were carefully read and analyzed. The quantitative analysis demonstrated that from among the four discourse markers, “you know” and “you see” were the most and the least frequent ones in the corpus, respectively. In line with the quantitative analysis, the qualitative analysis of the concordance lines demonstrated that there were various functions with regard to each of the four discourse markers. The findings of this study can have implications in fields such as corpus-based studies, genre analysis, and contrastive linguistics.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Discourse markers have been an intriguing topic of research in pragmatics. They play a pivotal role in pragmatic competence of speakers (Müller, 2005; Lam, 2009; Öztürk & Durmuşoğlu Köse, 2020) and will help them to make their speech more comprehensible and rich (Crozet, 2003) as well as more sociable (Weydt, 2006). In addition, discourse markers perform various functions relating to turn taking management as well as speaker-audience relationship (Crible, 2017) as they are defined and detected mostly by the various functions they (can) perform (Aijmer, 2013).

The concept of discourse markers has intrigued researchers to investigate their different forms and functions in speech and writing. Indeed, the interest in studying discourse markers stems from the fact that they are pragmatically variant or multifunctional (Schleef, 2005; Lee, 2017). This wide range of functions have resulted into the introduction of various terminologies such as sentence connectives (Fraser, 1999; Halliday & Hasan, 1976), discourse particles (Schourup, 1985), discourse signals (Lamiroy & Swiggers, 1991), discourse connectives (Unger, 1996), discourse particles (Aijmer, 1997, 2002), speech act adverbials (Aijmer, 1997), discourse operators (Gaines, 2011), thetical features (Heine et al., 2016), pragmatic markers (Brinton, 2017) and metadiscourse features (Hyland, 2004, 2019).

In line with these various terminologies, there is a range of homogenous definitions. To name a few, Hyland (2004) defines discourse markers as “a self-reflective linguistic expression referring to the evolving text, to the writer, and to the imagined readers of that text” (p. 133). In the same line, Vande Kopple (2012) defines these features as “elements of texts that convey meanings other than those that are primarily referential” (p.37). In another definition, Ädel (2010) defines discourse markers as “reflexive linguistic expressions referring to the evolving discourse itself or its linguistic form, including references to the writer-speaker qua writer-speaker and the (imagined or actual) audience qua audience of the current discourse” (p.75).

Discourse markers have specific characteristics, which make them distinguished from other linguistic elements. As an example, Hyland (2019), while referring to metadiscourse markers as the terminology, assigns three distinguishing roles to them: these features must be distinguished from propositional aspects of meanings because they are inherently non-propositional; they consider those aspects of discourse which are used to establish writer-reader and/or speaker-audience interaction; and they can have various functions in different contexts.

The term “discourse marker” has been the subject of a range of studies over the last decades. It can have miscellaneous functions, extending from signals, which function as hesitation filters, to clausal expressions, which are frequently used and found in spoken interactions. There are some studies focusing on the multifunctionality of discourse markers such as Mauranen (2001), Thompson (2003), Farrokhi and Ashrafi (2009), Crismore and Abdollahzadeh (2010), Letsoela (2014), Ma and Wang (2015), Ghasemali and Azizeh (2017), Akbas and Hardman (2018), Hajimia (2018), and Jalilifar (2008). These studies studied various discourse markers from different perspectives such as genre, language variations, grammaticalization, and native and non-native language.

Language as a means of communication plays a significant role in everyday life because “all people use spoken language to interact with one another” (Zarei & Mansoori, 2007; Povolná, 2010, p.23). Although spoken and written languages are interdependent (Townend & Walker, 2006), spoken language has some specifications which make it different from written language. Cook (2004) accentuates the differences between spoken and written forms of language by saying that “Many of the devices of written language have no spoken equivalent” (p. 12) which can be the result of differences in the mode or in the context of usage. In this regard, one difference is that unlike the written form, spoken language does not have the opportunity for self-revision and editing on the spot (Crawford & Csomay, 2016). Another difference is the matter of formality in speech versus written modes, meaning that in spoken mode, there are more instances of informality.

A detailed look at the literature review supported this idea that there was a lack of research in the area of discourse markers in spoken language, despite the fact that in written language, there were a plethora of studies (see, for example, Erman, 2000; Chapetón & Claudia, 2009; Kohlani, 2010; Ismail, 2012; Sharndama & Yakubu, 2013; Dylgjeri, 2014; Piurko, 2015; Crible et al., 2019). This can be due to the fact that collecting spoken data, as compared to written data, is a more overwhelming issue, which requires too much budget and time (Burnard, 2002).

Despite the lack of solid research in spoken discourse with the exploitation of large corpora, in one of the rare studies, Huang (2011) studied the spoken discourse markers between Chinese non-native speakers (NNSs) of English and native speakers (NSs). Using linear unit grammar analysis and text-based analysis and applying SECCL, MICASE, and ICE-GB corpora, the results of this corpus-based research showed that discourse markers such as “like,” “oh,” “well,” “you know,” “I mean,” “you see,” “I think,” and “now” are found more frequently in dialogue genres as compared to monologue genres in spite of the similarities found between NNSs and NSs. In addition, the results of this research showed that discourse markers correlate with context, type of activity, and identity of the speakers.

In another related research, Novotana (2016) studied the role of discourse markers as well as their functions in spoken English. For this purpose, he chose 19 discourse markers such as “I see,” “you know,” “I mean,” “actually,” and “really,” among others. The analysis of his corpus demonstrated that not only do discourse markers play a pivotal role in English spoken mode, but also they can have various functions, depending on the intention of the speaker(s) and the context of usage.

In addition, Kizil (2017) studied the function and frequency of discourse markers in learners’ spoken interlanguage of EFL learners. With two corpora of reference and learner, he showed that as far as audience interaction is concerned, non-native speakers used fewer discourse markers as compared to native speakers, which can be attributed to their unawareness of the significant role of discourse markers.

In the same vein, Resnik (2017) investigated the function and distribution of discourse markers (metadiscourse features) in spoken interaction as a strategy for compensating miscommunication among multilingual speakers who communicate in their L2 (English). For this objective, she conducted 27 interviews for creating a corpus of spoken English. The analysis showed that L2 speakers of English employ metadiscourse features as a means of enhancing mutual understanding and that depending on the situation, they bear different functions.

In the same vein, Jong-Mi (2017), investigated the multifunctional nature of “Okay” as a discourse marker used by Korean EFL (English as a foreign language) teachers in their naturally occurring discourses of EFL classes. The data gathered from video recordings of six Korean teachers demonstrated that discourse marker “Okay” can take three different roles as “getting attention”, “signaling approval and acceptance as a feedback device,” and “working as a transition activator.”

In a recent study, Banguis-Bantawig (2019) investigated the functions of discourse markers in speeches of selected Asian Presidents. Adapting the discourse theory of Hassan and Halliday and de Beaugrande and Dressler in analyzing 54 English speeches of Presidents in Asia, he showed that there were three pivotal roles in relation to discourse markers used by presidents including adding something to the speech, cohesion, and substitution.

A look at the above-mentioned studies indicated that they were mostly limited to small-scaled corpora, jeopardizing the generalizability of their results as well as corpus representativeness. Moreover, the review of the related literature showed that the studies in this area of research lacked the exploitation of large, balanced, and representative corpora in spoken discourse. Consequently, based on the insight gained from literature review and due to the research aims, this study was an effort to fill out this less researched gap and area of research by addressing these two questions: (1) How were the above-mentioned discourse markers used and distributed in the British Academic Spoken English (BASE) corpus and which discourse marker was the most frequent one? and (2) Which functions did these discourse markers have in the context of use in spoken discourse? The null hypothesis of this study was that there was no difference in terms of discourse marker distribution in the corpus of the study and that there was no difference in terms of the function(s) of the discourse markers in the corpus of the study.

2 Theoretical framework

The framework of the present study is Discourse Grammar (Kaltenböck et al., 2011) which as proposed by Heine et al. (2013, 2020) rose out of the analysis of spoken and written linguistic discourse on the one hand and of the work conducted on thetical expressions on the other. In other words, it is based on the distinction between two organizing principles of grammar where one concerns the structure of sentences (sentence grammar) and the other the linguistic organization beyond the sentence (thetical grammar). The term theticals, including DMs, is sometimes used interchangeably with extra-clausal constituents (ECC) or parentheticals (see Dik, 1997: 379–409) and encompasses various constituents such as vocatives, imperatives, social exchange formulae, interjections, and conceptual theticals.

Discourse Grammar is a relatively new framework providing a detailed description and explanation of DMs, their functions, and evolution. Accordingly, the thetical grammar is based on the speaker’s communicative intents and the knowledge of discourse processing at a higher level, relating the text to the situation of discourse. The situation of discourse refers to the cognitive frame used by interlocutors to construct and interpret spoken or written texts; it is delimited by three components, namely, (i) text organization, (ii) attitudes of the speaker, and/or (iii) speaker-hearer interact. The last two are sometimes called interpersonal [or modal] functions and relate, respectively, to the terms “subjectivity” and “intersubjectivity” (Heine et al., 2020).

In this framework, a distinction is provided between two organizing principles of grammar, where one concerns the structure of sentences (sentence grammar) and the other the linguistic organization beyond the sentence (thetical grammar). Kaltenböck et al. (2011) and Heine (2013) have introduced the specification in (1) to describe a prototypical thetical.

-

(1)

Theticals are (a) invariable expressions which are (b) syntactically independent from their environment, (c) typically set off prosodically from the rest of the utterance (which can be marked by comma in writing), and (d) their function is to relate an utterance to the situation of discourse, that is, to the organization of texts, speaker-hearer interaction, and/or the attitudes of the speaker (Heine, 2013, p. 1211).

3 Procedure and detection of the discourse markers

This study privileged both quantitative and qualitative phases. In the quantitative study, the frequency of the detected discourse makers was calculated through the statistical procedures and in line with the criteria mentioned above. In the qualitative phase, the extracted concordance lines were scrutinized to unveil the function(s) of the detected discourse markers. Accordingly, an array of steps was taken for the issue of feasibility. First, we scrutinized the whole corpus of the study, through the concordance lines and CQL (Corpus Query Language) technique in Sketch Engine Corpus Software to detect the tokens of discourse markers. In order to distinguish discourse markers from other types of non-prepositional elements, we exploited the criteria set by Kaltenböck et al. (2011) as come in (1).

Following the conditions, four discourse markers were selected in this study including “I mean,” “you know,” “you see,” and “I think.” These were selected due to their higher frequency and dispersion in the corpus and due to their similarity that is all can be followed by the complementizer “that” in the level of sentence grammar. In other words, they were among the most frequent discourse markers in the corpus, and they can receive a subordinate clause when used as an intendent clause. Table 1 shows the frequency of discourse markers of the study. It is worth mentioning that in order to be able to unpack the function(s) of these discourse markers, we analyzed the linguistic context surrounding the discourse marker as well as the topic of the discussion. It should be noted that it is problematic to intuitively interpret the functions of discourse markers, as most previous studies have done, because a researcher cannot read a speaker’s mind; in most cases, the uses of DMs are not even easily available to introspection by the speaker. As a result, this study used the immediate context and the co-occurrence phenomena to categorize the uses of discourse markers and to clarify the logic of the identification of their functions. However, occasionally more than one type of co-occurrence is found in the same instance. In cases of this kind, the classification has to be confirmed by the use of other discourse markers in the context.

Table 1 shows the type and frequency of the discourse markers of the study. As can be seen, from among 4 types of discourse markers, “I mean” had 1888 frequency. Then, was “I think” discourse marker with 2940 tokens, followed by “you know” with 3569 tokens and “you see” with 506 tokens. On aggregation, there were 8903 tokens of the 4 discourse markers in the corpus.

4 Corpus of the study

Rather than the rudimentary and time-consuming process of detecting the existing similarities and differences out of the immediate context, researchers resort corpora to explore the differences and similarities of a language(s) in the immediate context of use (Zanettin et al., 2003; Anderman & Rogers, 2008; Candel-Mora & Vargas-Sierra, 2013, Milagrosa Pantaleon, 2018). As a matter of fact, comparing to extract and analyze language features manually which is not only time-consuming but also subject to error (Anthony, 2009), one plausible way is to apply corpora defined as “an electronically stored, searchable collection of texts” (Jones & Waller, 2015, p.6). Corpora are useful in that they can give the researcher(s) a quick access to the word/phrase as well as to the context in which it is used (Anderman & Rogers, 2008). As a result, having access to a representative and balanced corpus that could meet the requirements of the study was an integral part of this research (Heng & Tan, 2010).

As creating a Do It Yourself (DIY) corpus was inherently an arduous task and was beyond the scope of the current research, we decided to employ already compiled and available corpora. There are a number of various academic spoken corpora such as the Michigan Corpus of Academic Spoken English (Nesi & Thompson, 2006) and Hong Kong Corpus of Spoken English (Cheng & Warren, 1999); however, from among these spoken corpora, the one, which was exploited in this study, was “The British Academic Spoken English (BASE) corpus.” The reason why this corpus was used was due to its availability in Sketch engine corpus software and its fitness to this study. This corpus was compiled at the Universities of Warwick and Reading out of 160 lectures and 39 seminars video recorded from 2000 to 2005. The male and female speakers were both native and non-native speakers of English (Thompson & Nesi, 2001). As its name implies, it is narrowed down to academic genre and contains such fields of studies as arts and humanities, life and medical sciences, physical sciences, and social studies and sciences. The corpus contains 1,756,545 words and 1,477,281 sentences. This specialized, representative, and balanced corpus, which was tagged at part of speech (POS), was used in this research to be in line with the research boundary of the study in hand.

5 Quantitative analysis

This study was done in two phases of quantitative and qualitative analysis. As for the quantitative analysis, the frequency of each of the discourse markers was calculated separately through the whole corpus. The results are presented in the following tables. The data analysis was done through SPSS version 26.

Table 2 demonstrates the frequency of discourse markers in the corpus. As can be seen, there were 8037 tokens of discourse markers from among which “you know” was the most frequent one with 3188 tokens followed by “I think” and “I mean” with 2578 and 1786 tokens. The least frequent type of discourse marker was “you see” with only 485 tokens.

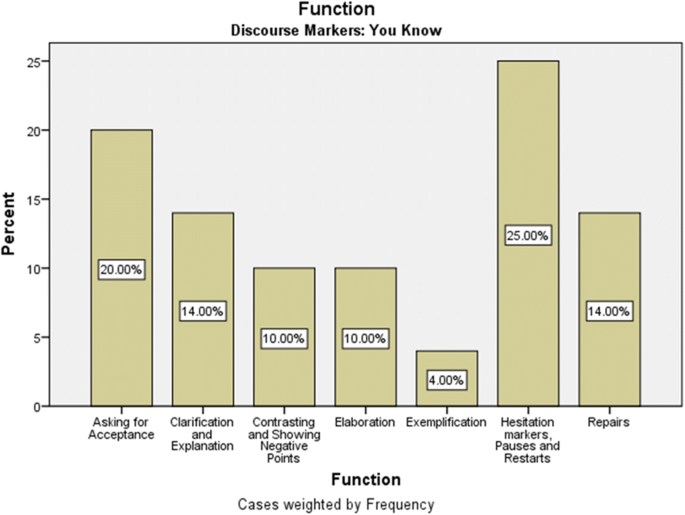

Figure 1 shows the functions of the “you know” discourse marker. As can be seen from among seven functions, hesitation markers and asking for acceptance were the two most frequent functions with 25% and 20%, respectively, followed by clarification function and repairs as the third used discourse markers (14%). Next were contrastive function and elaboration function with 10% followed by exemplification as the least frequent function (4%).

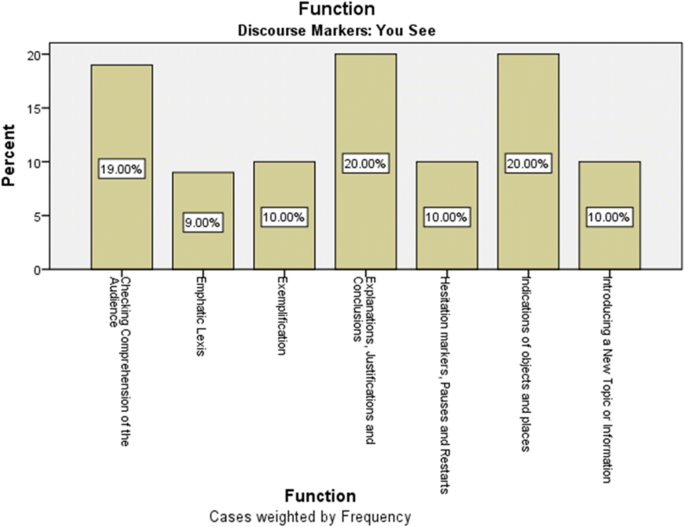

Figure 2 indicates the functions of “you see” discourse marker. As can be seen, from among these functions, indication of objects and explanations were the most frequent discourse markers (20%) followed by checking comprehension as the second most frequent function (19%). With 10%, introducing new topic, hesitation markers, and exemplification were the third most frequent functions. Emphatics function with only 9% was the least frequent function.

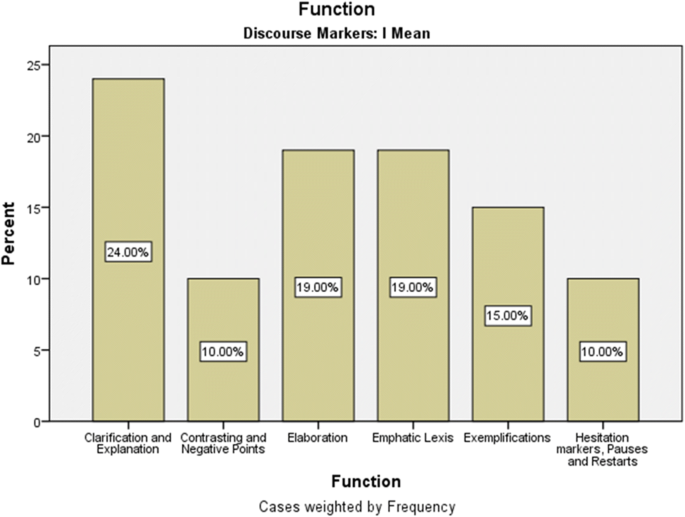

Figure 3 indicates the functions of “I mean” discourse marker with their frequency. As can be inferred, clarification and explanation were the most frequent function with 24% followed by elaboration and emphatic lexis with 19%. In the third rank was exemplification with 15%. The least used functions were hesitation and contrasting ones with 10%.

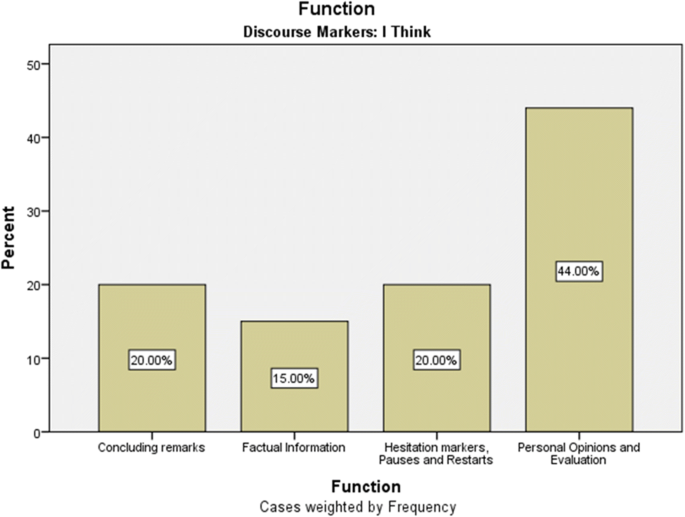

Figure 4 represents the functions of “I think” with four ones. As can be inferred from the figure, personal opinion with 44% was the most frequent function followed by concluding remarks and hesitation remarks as the second most frequent functions (20%). The least used function was factual information with 15%.

6 Qualitative analysis

Once the quantitative analysis was done, the qualitative analysis was conducted through close reading of the concordance lines. It is worth mentioning that 30% of the concordance lines were randomly selected through shuffling technique of the corpus software to unpack the functions of discourse markers.

7 Functions of “you know” discourse marker

The first discourse marker that was studied in this research was “you know.” The close reading of the concordance lines showed that there were 7 various functions in relation to “you know” discourse marker. The functions were as the following:

-

1:

Hesitation markers, pauses, and restarts

The first function in relation to “you know” discourse marker is hesitation, pause, and restates. It is worth mentioning that this function is one that usually overlaps the other functions such marker has in its discourse situation. As can be seen in the excerpt, the speaker is searching for a reason, and it seems probable that “you know” is used with a repetition of the initial word of the reason statement, i.e., “we,” to stall for time, find a suitable way to express a negative point.

-

Example 11

you have so in actual fact we did not learn anything so what did you learn how to do it better next time I reckon if we did it again though we’d just do the same because we you know we did not have an idea of we just did not think about.

-

2:

Repairs

The second function with regard to “you know” discourse marker is to repair a speech. In Example 1, “you know” prefaces “and this” to repair the previous pronoun “they” in “and they.” In this case, “you know” is also used as a hesitation marker which is reinforced by repetition of pronoun “they.”

-

Example 1

I think Motorola have been in the business for a good many years so and they and they you know and this is the latest generation of many generations of processors so do you think they’ll if we have a lot of multiplications to perform.

“You know” in Example 2 also seems to mark a self-repair. It suggests a correction formulated for “a sort of static” which is followed by the corrected expression “an essentially static sort of framework.”

-

Example 2

They’re more likely to build models which are based on a sort of static you know an essentially static sort of framework which…

-

3:

Clarification and explanation

The third function in relation to “you know” discourse marker is to clarify and explain something. In Example 1, “you know” is followed by a clarification of what the speaker means by “a nice model to use,” and in Example 2, it prefaces a further explanation for “an individual leaf.”

-

Example 1

so if somebody comes along and gives you a model or tell say your supervisor or whatever comes along eventually and says here’s a nice model to use you know it’s a good one we use it round here everybody likes it round here the things to know are what are the approximations that went into your model and a lot of people are not very good.

-

Example 2

I am talking about individual leaf you know an individual leaf exposed to different levels of carbon dioxide

-

4:

Elaboration

The next function associated with the function of “you know” is elaboration. It occurs in situations where the speaker intends to elaborate on a proposition. In Examples 1 and 2, “you know” prefaces elaborations and can serve as a cue for the listeners of the coming details.

-

Example 1

So if you yeah i do not know unless of course unless of course you know you just have the somebody held the long rope and tied it on one of these sides yeah if you go on that side.

-

Example 2

you know when i say write in a write in a limerick write me a sonnet write me twenty lines of this write me five lines of this I’m asking you to do that in order to practise rather than to produce great works of art.

-

5:

Exemplification

Another function in relation to “you know” discourse marker is to make exemplification. In Examples 1 and 2, “you know” is followed by two examples, i.e., “one decimal point” and “a million,” by which the number differs; Africa, Burma, and Cambodia are also some examples of those countries which enjoy international communication.

-

Example 1

They will go for that combination of goods rather than one to which we have allocated a lower number how much the number differs is irrelevant it could differ by you know one decimal point or it could differ by a million.

Example …

That is part of the globalisation as well i mean globalisation of international communication and technology you know even the people in in Africa or you know in in Burma or in Cambodia they have access to the internet now

-

6:

Contrasting and showing negative points

“You know” is also found to be followed by some contrastive and negative points, as in Example 1 where the speaker is intending to cushion the impact of the comment.

-

Example 1

It seems that the first half has to be the kind of thing you’d present to like somebody who does not really have any you know deep technical knowledge of it i do not think you would necessarily interpret it like that but suppose it.

-

7:

Asking for acceptance

A number of instances of “you know” may be used to claim consensus. This function is reinforced by the repetition of “yeah” in Example 1 and by the adverb “certainly” in Example 2.

-

Example 1

you know yeah if you are all doing your separate thing follow somebody’s idea yeah even if it’s the wrong idea to a certain extent you need to give them a chance.

-

Example 2

please do not be shy you know i almost certainly anything you say will not be used and if it’s outstandingly good then it will be used and you’ll be beautifully happy okay if you sort of you slip on something do not bother it.

8 Functions of “you see” discourse marker

The second discourse marker, which was studied, was “you see” discourse marker. The close reading of the concordance lines showed that there were seven various functions with regard to this discourse marker. These include (1) hesitation markers, pauses, and restarts; (2) emphatic lexis; (3) exemplifications; (4) explanations, justifications, and conclusions; (5) indications of objects and places; (6) shared knowledge presumed by the speaker; and (7) for checking comprehension. Some of these functions are shared with “you know” and have previously been discussed and exemplified. The relevant examples are provided in this section, too.

-

1:

Hesitation markers, pauses, and restarts

-

Example 1

so I can order this week what did you say four-thousand safety stock no if you want to have it is four-thousand you see this week this week we are predicting six-thousand-five-hundred in demand okay two thousand-five-hundred not six-thousand-five-hundred.

-

Example 2

If we just try to describe it is like a diary i mean you describe something but i mean you see other people can see little point in them so normative theories and descriptions must come together

-

2:

Exemplification

-

Example 1

Whereas the other person might say but you see just think of how she must be feeling right now which is quite different logic somehow we reach an understanding.

-

Example 2

not surprisingly you see particularly for East Asia and the Pacific there was just under ten per cent trade was in goods was just under ten per cent of G-D-P in nineteen-eighty-seven it was just under fifteen per cent in nineteen-ninety-seven.

-

3:

Explanations, justifications, and clarification

-

Example 1

AIDS is an acronym yeah you see the difference in some languages they turn all their initialisms into acronyms.

-

Example 2

how can we make this sort of inference you see what I am stating maybe just the ob obvious but by stating the rather obvious maybe i hope that we begin to see something.

“You see” is rather different from the discourse marker “you know” in that it is used as a device to move the hearer’s attention to the intended objects and places. Furthermore, it co-occurs with emphatic lexis like “only” and “quite,” as in Example 1 and or with some new information in Example 2.

-

4:

Indications of objects and places

-

Example 1

that’s you see the interesting thing ‘cause seeing that you think it’s going to unwind so the bobbin’s going to have to go to the left in fact that’s impossible it always goes to the right if you pull on anything in one direction it will go.

-

Example 2

we were trying to pass the list as a parameter which did not really work ah yeah now you see that’s where we had problems with the quick sort algorithm and and we made a scratch list as well.

-

5:

Emphatic lexis

-

Example 1

we are at a low level so that there’s no idea for a start and the buildup is gonna be less if you see only for this period because after this peak we alw we are gonna be changed with something like that.

-

Example 2

and i think even at at the back of the room you should be able to read that just but you see there’s quite a difference so this is the largest late eighteenth century display.

-

6:

Introducing a new topic or information

-

Example 1

now you see that’s where we had problems with the quick sort algorithm and and we made a a scratch list as well did not we the conventional algorithms.

-

Example 2

maybe there’s a synthesis coming maybe you see in buildings like B-A hes headquarter building the synthesis if you like of user value exchange value some notion of business value

-

7:

Checking comprehension of the audience

A speaker can use “you see” to check the hearer’s comprehension and to find what to say later. In Example 1, the speaker repeats “so I mean” after checking the hearer’s comprehension by using “you see.” Such discourse marker can be interpreted as a short form of “do you see?” based upon the contextual information.

-

Example 1

so i mean i learned quite a lot first comes the teacher action and well philosophers are rather notorious for saying something obvious philosophers just say if P then Q P therefore Q ah God i mean how how how can we make this sort of inference you see so i mean what I am stating

-

Example 2

it has not got an A on it at the end you see oh i thought i changed it okay let us say change yeah is it is it alright now i say okay the answer’s no.

9 Functions of “I mean” discourse marker

“I mean” is found to function as (1) hesitation markers, pauses, and restarts; (2) repairs; (3) clarifications and explanations; (4) elaborations; (5) exemplifications; and (6) contrasting and negative points. These functions are shared with “you know” which have previously been discussed. Thus, due to the limited space, each of the overlapping types of co-occurrence is only illustrated with two examples in this section.

-

1:

Hesitation markers, pauses, and restarts

-

Example 1

so the workings of the exhibition of the gallery become the artwork so he’s taking like the gallery as an artwork well yeah i mean very literally revealing what makes the behind the the gallery function.

-

Example 2

this is a very important relationship i mean in some sense in in the theory of radiative transfer this was the first really quantitative law that was discovered.

-

2:

Repairs

-

Example 1

so that’s more appropriate then for them to look at a sort of i mean it does say detailing any business plan.

-

Example 2

you have to be careful not to i mean it’s it’s kind of difficult but you have not to give too much not to make up meaning for it so we we have sort of tried to make a criticism on his work.

-

3:

Clarification and explanation

-

Example 1

if you just follow it blindly yeah i mean it would be worse if we were all like having different ideas and all arguing about it.

-

Example 2

he had to buy get loans and sell his own things so in a way he is the kind of stuff he sells and he sells his own i mean it’s often a drawing and then a map next to it and then the model.

-

4:

Elaboration

-

Example 1

and radar does anyone know what it is i mean you might not you might think that radars measure rainfall.

-

Example 2

you must do one question from either section A or section B and the section A questions are related to the seminar topics i mean there will be essentially one on each seminar topic.

-

5:

Exemplifications

-

Example 1

and the implications as to why you went down a certain route you know is not it i mean why it sort of mentions if someone says well.

-

Example 2

he does seem really to invite these sort of complete projections of everything onto the work i mean he has even been categorised as the kind of central artist of his era.

-

6:

Contrasting and negative points

-

Example 1

you know adopting the political strategies of you know almost any public project which needs to come off the ground well i mean I am not sure if i’d put it yeah well he said like when we were talking about the money.

-

Example 2

but i mean that’s that that is that is a very neo-realist sound in a way that some of the other things you have heard are much less obviously so i’ll come back to that question.

10 Functions of “I think” discourse marker

-

1:

Hesitation markers, pauses, and restarts

It can be argued that “I think” can co-occur with hesitation markers and pauses to give the speaker the time to search for content information or appropriate lexical expressions. This type of co-occurrence seems to suggest that the speakers are using “I think” as a filler while formulating what to say next. In the second example below, the speaker stalls for more time after “I think” by adding “mm” or “okay.”

-

Example 1

yeah people cause people give i think they you are provided you need aren’t you they they have done this before they would have seen if it was possible.

-

Example 2

i think mm okay that’s your lot mine aren’t terribly neat but and i got one wrong while i was writing it.

-

2:

Personal opinions and evaluation

“I think” is frequently used to express personal opinions and evaluation. In Example 1, there are two types of co-occurrence, the first with positive evaluation and the other with personal opinion about the relevant topic. The instance of “I think” in Example 2 co-occurs with a personal opinion, too. Here, “I think” seems to be multifunctional, of course, and is used as a hesitater before launching the sentence, as well.

-

Example 1

-

Do you four want to make some some comments on on that

-

Well I think its good too I think it could still be slimmed down a little bit.

-

-

Example 2

So he’s taking like the gallery as an artwork well yeah I mean very literally revealing what makes the behind the the gallery function as a gallery pause I think that’s the easiest gesture.

-

3:

Factual information

Another function of “I think” is to co-occur with factual information. This is in line with Coates (2003) who claims that expressions like “I think” which are conveying some kind of uncertainty do not necessarily reflect actual uncertainty but are applied as a sign to avoid sounding too assertive. In Example 1, “I think” seems to either mark genuine uncertainty about the fact, today’s session is going to be the last of the lecture sessions for the course, or simulate uncertainty in order not to sound too assertive. In case of Example 2, it is difficult to argue for the (un)certainty of the speaker about the fact, and the use of discourse marker helps reduce the commitment. Based upon the encyclopedic knowledge, the speaker, as well as the hearer, does know Motorola have been in the business for a good many years, and “I think” can be possibly used to downplay the authority.

-

Example 1

I wanted to say to you this morning is that I think w today’s session is going to be the last of the lecture sessions for the course or if it is not there’ll only be about ten.

-

Example 2

I think Motorola have been in the business for a a good many years so and they and they you know and this is the latest generation of many generations of processors

-

4:

Concluding remarks

“I think” is also found to co-occur with some personal conclusion when collocating with such concluding connectors as “so” or “therefore.” In Example 1, the first “I think” is used to express a personal opinion; however, the one after “so” is prefacing a concluding remark, although it is still a personal one. “I think,” in Example 2 encapsulates the ideas in the previous context, which are not shown here to the interest of space and are available in BASE corpus, to reduce the effect of imposing that personal conclusion on the hearer(s).

-

Example 1

i think you’d do it easier with link lists as well actually so i think i think you are right

-

Example 2

they might not wish their discussions with their lawyer to be disclosed the effect of Condron and Condron therefore i think is to create some considerable dilemmas

11 Discussion

Discourse markers can have various functions when they are used in different contexts. Apart from the context, the mode of communication can exert an effect on the usage and function of discourse markers (Li, 2004; Al Rousan et al., 2020). As for speaking, for example, “discourse markers are used constantly by speakers and play a significant role in speech, in particular in spontaneous speech” (Huang, 2011, p. 7), which necessitates their study from a pragmatic point of view (Aijmer, 2002). For this purpose, this research was an effort to unveil the distributional frequency and the function(s) of four different types of discourse markers in the British Academic Spoken English (BASE) corpus as the data gathering source.

With regard to the first research question, the analysis of the quantitative data (Table 1) showed that “you know” was the most frequent discourse marker of the spoken English, whereas “you see” was the least frequent one. The functions associated with the four discourse markers were identified on the basis of the context they occurred in. It was also revealed that the discourse markers had their own particular functions in the spoken discourse.

These functions are summarized in Table 3.

The functions listed in the table can be split into two broad categories. The first eight items are primarily for textual organization, which help the process of text comprehension. For example, the use of discourse markers to exemplify, clarify, and explain gives the listeners a hint about the previous statement(s) to ease the comprehension. From the ninth item to the last, the items primarily contribute to the interpersonal aspect of interaction. All four discourse markers had their own textual function, and “you know” and “I mean” had their own roles with respect to the first six functions. The similarity in the functions “I mean” and “you know” has in the corpus is influenced by a variety of reasons. Among many, there are certain functions that make these DMs important in academic discourses. These DMs are considered markers that indicate some sort of information between interlocutors as an indication to acknowledge the understanding of the other party. Last but not least, in line with what Schiffrin (1987) Maynard (2013) claim, the semantic meaning of the two DMs “I mean” and “you know” would influence their discourse function. The first singular pronoun “I” in the DM “I mean” orients toward the speaker’s own talk where the DM you know orients toward the addressee’s knowledge (Schiffrin, 1987), and this would help the DM “you know” to occur more in academic contexts with an extra function “asking for acceptance.” This use of DM would be helpful in such discourses where the aim is to claim the acceptance of the audience. To put it differently, the reason why “you know” was the most frequent type of discourse marker could be due to the fact that (a) it carries an expectancy of meaning comprehension on the behalf of the audience and (b) the expectancy of understanding requires the audience to act accordingly and accept what the speaker intends. This expectation of understanding is in line with the inherent meaning of “you know.” Apart from this, this discourse marker may act as a signal for the audience so that he can pay attention to the message delivered from the speaker.

“I think” and “you see” also have their own function, but this is only “you see” that has interpersonal function of attracting the listeners’ attention by mentioning a place, for example. The distribution and function of the DM “I think” with a cognitive-verb based constructions have a more determinate semantic meaning, viz. I think encodes the speaker’s own thought, and this DM, as compared to the other three DMs, implies a more particular cognitive disposition of the speaker referring to his/her recontextualized opinion. This may lead to more frequent “I think” with interpersonal functions than textual ones, and still the reason for the most frequent function, i.e., announcing personal opinions and evaluation. Another explanation besides the indexical references to the speaker and its interactional role would be the fact that, in spoken discourse, the speaker exploits self-references as a means of showing his presence and proving claims, propositions, findings, and ideas. The application of the self-mentions through the DM “I think” can add support to the idea that the authors were representing scholarly identity through the interaction with their audience and projected not only themselves but also their claims about propositions. The presence of “I” as part of the DM “I think, like “I mean,” shows the presence of the author in such a way that authors shape, establish, and promote personal competence and identity in their speech.

With regard to the “you see” discourse marker, it has similarity, to some extent at least, to “you know” discourse marker in that both have the pronoun “you” which is a signal of mutual understanding and cooperation. Like “you know” discourse marker, there is a clandestine expectancy of understanding on the behalf of the audience. In other words, the speaker uses this discourse marker as an indication that he wants the audience to accept/understand something and act accordingly.

The results of this study resonate with those of Erman (2000), Chapetón and Claudia (2009), Ismail (2012), Piurko (2015), Kizil (2017), Crible et al. (2019), and Banguis-Bantawig (2019). They showed that discourse markers could receive various functions when they are used in different contexts in spoken or written modes.

12 Concluding remarks

From the analysis of the corpus, it can be seen that all the four discourse markers were multifunctional based on their context of usage in spoken English. This characteristic of multifunctionality makes them different from the parallel form(s) as an independent clause. Indeed, the results of this research showed that in spoken discourse, discourse markers are used to serve various functions depending on the context of usage and the intention(s) of the speaker(s). This means that the use of discourse markers is context-sensitive, not context-free, and can range from hesitation markers, clarifications to exemplification, and indication of objects.

The results obtained from this study can bear useful implications for researchers in the domain of linguistics, rhetoric, and discourse analysis. They can read the findings of this study to understand how discourse markers can have different functions in different contexts in spoken mode. In addition, the findings of this study can have practical implications for researchers in corpus-based language studies as the data gathering section of this paper can be useful for them.

This study can be an incentive for further research. As an example, it is an interesting idea to study the function(s) of discourse markers in various genre of spoken language (for example formal vs. informal or academic vs. non-academic) to see how they are used and which functions they have in speech. Moreover, it can be an intriguing area of research to unveil the function(s) of discourse markers in spoken and written language to see how they are used in two different modes of communication. Gender can be another interesting area of research. It deserves attention to see how discourse markers are used by female and males in written and spoken discourse. Translating discourse markers can also attract the attention of further research. It is an intriguing area of research to investigate the way discourse markers are translated through parallel corpora. Discourse markers can bear functions in various genres. As a result, the last but not the least suggestion can be analyzing the function(s) of discourse markers in various genres with the aim of analyzing and comparing various genres.

Despite the positive and constructive results, this study had some limitations, which require the attention of future researchers. First and foremost, this study was limited to one corpus only. An integral part of corpus study is corpus balance, which means utilization of various corpora (Mikhailov & Cooper, 2016). There are some other spoken corpora for tackling this problem such as TED talks transcripts, BNC 2014 spoken corpus, EUROPARL7, and English and Open American National Corpus (Spoken). All of these corpora are available free at Sketch engine Corpus Software. Apart from that, this study was limited to four discourse markers. These two limitations call for further research.

References

Aijmer, K. (1997). “I think” – An English modal particle. In T. Swan & O. J. Westvik (Eds.), Modality in Germanic Languages. Historical and Comparative Perspectives (pp. 1–47). Mouton de Gruyter.

Aijmer, K. (2002). English discourse particles: Evidence from a corpus. Benjamins.

Aijmer, K. (2013). Understanding pragmatic markers. Edinburgh University Press.

Akbas, E., & Hardman, J. (2018). Strengthening or weakening claims in academic knowledge construction: A comparative study of hedges and boosters in postgraduate academic writing. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 18(4), 831–859.

Al Rousan, R., Al Harahsheh, A., & Huwari, F. (2020). The pragmatic functions of the discourse marker bas in Jordanian spoken Arabic: Evidence from a corpus. Journal of Educational and Social Research, 10(1), 130. https://doi.org/10.36941/jesr-2020-0012

Anderman, G. M., & Rogers, M. (2008). Incorporating corpora: The linguist and the translator (1st ed.). Multilingual Matters.

Anthony, L. (2009). Issues in the design and development of software tools for corpus studies: The case for collaboration. In P. Baker (Ed.), Contemporary corpus linguistics (pp. 87–104). Continuum.

Banguis-Bantawig, R. (2019). The role of discourse markers in the speeches of selected Asian presidents. Heliyon, 5(3), e01298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01298

Brinton, L. J. (1996). Pragmatic markers in English: Grammaticalization and discourse functions. Mouton de Gruyter.

Brinton, J. (2008). The comment clause in English: Syntactic origins and pragmatic development (studies in English language). Cambridge University Press.

Burnard, L. (2002). Where did we go wrong? A retrospective look at the British national corpus. In B. Kettemann & G. Markus (Eds.), Teaching and learning by doing corpus analysis (pp. 51–71). Rodopi.

Candel-Mora, M. A., & Vargas-Sierra, C. (2013). An analysis of research production in corpus linguistics applied to translation. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 95, 317–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.10.653

Chapetón, C., & Claudia, M. (2009). The use and functions of discourse markers in EFL classroom interaction. Profile Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 11, 57–78.

Cheng, W., & Warren, M. (1999). Facilitating a description of intercultural conversations: The Hong Kong corpus of conversational English. ICAME Journal, 23, 5–20.

Coates, J. (2003). The role of epistemic modality in women’s talk. In R. Facchinetti, M. Krug, & F. Palmer (Eds.), Modality in Contemporary English. Mouton de Gruyter.

Cook, V. (2004). The English writing system. Hodder Headline Group.

Crible, L. (2017). Towards an operational category of discourse markers. A definition and its model. In C. Fedriani & A. Sanso (Eds.), Pragmatic markers, discourse markers and modal particles (pp. 97–124). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Crible, L., Abuczki, Á., Burkšaitienė, N., Furkó, P., Nedoluzhko, A., Rackevičienė, S., & Zikánová, Š. (2019). Functions and translations of discourse markers in TED Talks: A parallel corpus study of underspecification in five languages. Journal of Pragmatics, 142, 139–155.

Crismore, A., & Abdollahzadeh, E. (2010). A review of recent metadiscourse studies: The Iranian context. Nordic Journal of English Studies, 9(2), 1–25.

Crozet, C. (2003). A conceptual framework to help teachers identify where culture is located in language use. In J. L. Bianco & C. Crozet (Eds.), Teaching invisible culture: Classroom practice and theory (pp. 34–39). Language Australia.

Dylgjeri, A. (2014). The function and importance of discourse markers in political discourse. Beder University Journal of Educational Sciences, 1/5, 26–35.

Erman, B. (2000). Pragmatic markers revisited with a focus on you know in adult and adolescent talk. Journal of Pragmatics, 33(9), 1337–1359. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-2166(00)00066-7

Farrokhi, F., & Ashrafi, S. (2009). Textual metadiscourse resources in research articles. Journal of English Language, 52(212), 39–75.

Fleischman, & Waugh, L. R. (Eds.). (2021). Discourse-pragmatics and the verb: The evidence from Romance (pp. 121–146). Routledge.

Fraser, B. (1999). What are discourse markers? Journal of Pragmatics, 31(7), 931–952.

Furk’o, P. B. (2020). Discourse markers and beyond, postdisciplinary studies in Discourse. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-37763-2_6

Gaines, P. (2011). The multifunctionality of discourse operator okay: Evidence from a police interview. Journal of Pragmatics, 43, 3291–3315.

Ghasemali, A., & Azizeh, C. (2017). The frequency of macro/micro discourse markers in Iranian EFL learners’ compositions. International Journal of English and Education, 6(1), 21–33.

Hajimia, H. (2018). A Corpus-based analysis on the functions of discourse markers used in Malaysian online newspaper articles. International Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Studies, 5(1), 19–24.

Halliday, M. A. K., & Hasan, R. (1976). Cohesion in English. Longman.

Heine, B. (2013). On discourse markers: Grammaticalization, pragmaticalization, or something else? Linguistics, 51(6), 1205–1247.

Heine, B., Kaltenböck, G., & Kuteva, T. (2016). On insubordination and cooptation. In N. Evans & H. Watanabe (Eds.), Insubordination. (Typological studies in Language) (pp. 39–63). Benjamins.

Heine, B., Kaltenböck, G., Kuteva, T., & Long, H. (2020). The rise of discourse markers. Cambridge University Press.

Heng, C. S., & Tan, H. (2010). Extracting and comparing the intricacies of metadiscourse of two written persuasive corpora. International Journal of Education and Development Using Information and Communication Technology, 6(3), 124–146.

House, J. (2013). Developing pragmatic competence in English as a lingua franca: Using discourse markers to express (inter)subjectivity and connectivity. Journal of Pragmatics, 59, 57–67.

Huang, L. F. (2011). Discourse markers in spoken English: A corpus study of native speakers and Chinese non-native speakers [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. The University of Birmingham.

Hyland, K. (2004). Disciplinary interactions: Metadiscourse in L2 postgraduate writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 13, 112–132.

Hyland, K. (2019). Metadiscourse: Exploring interaction in writing (2nd ed.). Bloomsbury.

Ismail, H. M. (2012). Discourse markers in political speeches: Forms and functions. Journal of College of Education for Women, 23/4, 1260–1278.

Jalilifar, A. (2008). Discourse markers in composition writings: The case of Iranian learners of English as a foreign language. English Language Teaching, 1(2), 114–127.

Jones, C., & Waller, D. (2015). Corpus linguistics for grammar: A guide for research. Routledge.

Jong-Mi, L. (2017). The multifunctional use of a discourse marker okay by Korean EFL teachers. Foreign Language Education Research, 21, 41–65.

Kaltenböck, G., Heine, B., & Kuteva, T. (2011). On thetical grammar. Studies in Language, 35(4), 852–897. https://doi.org/10.1075/sl.35.4.03kal

Kizil, A. S. (2017). The Use of metadiscourse in spoken interlanguage of EFL learners: A Contrastive analysis [Paper presentation]. Fırat University, Turkey.

Kohlani, M.A. (2010). The function of discourse markers in Arabic newspaper opinion articles. (Unpublished PhD dissertation). Washington: Georgetown University.

Lam, P. W. Y. (2009). Discourse particles in corpus data and textbooks: The case of well. Applied Linguistics, 31(2), 260–281. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amp026

Lamiroy, B., & Swiggers, P. (1991). Imperatives as discourse signals. In Suzanne Vande Kopple, W. (1985). Some exploratory discourse on metadiscourse. College Composition and Communication, 36, 82–93.

Lee, J. (2017). The multifunctional use of a discourse marker okay by Korean EFL teachers. Foreign Language Education Research, 21, 41–65.

Letsoela, P. M. (2014). Interacting with readers: Metadiscourse features in national university of Lesotho undergraduate students ‘academic writing. International Journal of Linguistics, 5(6), 138. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijl.v5i6.4012

Li, J. (2004). A study of the relations between discourse markers and metapragmatic strategies. Foreign Language Education, 6, 4–8.

Lu, Y. L. (2020). How do nurses acquire English medical discourse ability in nursing practice? Exploring nurses’ medical discourse learning journeys and related identity construction. Nurse Education Today, 85, 104–301.

Ma, Y., & Wang, B. (2015). A Corpus-based study of connectors in student writing: A comparison between a native speaker (NS) corpus and a non- native speaker (NNS) learner corpus. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature, 5(1), 113–118. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.5n.1p.113

Mauranen, A. (2001). Reflexive academic talk: Observations from MICASE. In R. Simpson & J. Swales (Eds.), Corpus linguistics in North America: Selections from the 1999 Symposium (pp. 165–178). Michigan University Press.

Maynard, D. W. (2013). Defensive mechanism: I-mean-prefaced utterances in complaint and other conversational sequences. In M. Hayashi et al.

Mikhailov, M., & Cooper, R. (2016). Corpus linguistics for translation and contrastive studies: A guide for research. Routledge.

Milagrosa Pantaleon, A. (2018). A corpus-based analysis of “for example” and “for instance”. The Asian ESP Journal, 14(7), 151–175.

Müller, S. (2005). Discourse markers in native and non-native English discourse. John Benjamins.

Nesi, H., & Thompson, P. (2006). The British academic spoken English corpus manual.

Novotana, R. (2016). The role of discourse markers in spoken English [Unpublished M.A thesis]. Brno.

Öztürk, Y., & Durmuşoğlu Köse, G. (2020). “Well (ER) you know …” Discourse markers in native and non-native spoken English. Corpus Pragmatics, 4(4), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41701-020-00095-9

Piurko, E. (2015). Discourse markers: Their function and distribution in the media and legal discourse (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Lithuanian University of Educational Sciences, Vilnius.

Redeker, G. (1990). Ideational and pragmatic markers of discourse structure. Journal of Pragmatics, 14(3), 367–381.

Resnik, P. (2017). Metadiscourse in spoken interaction in ESL: A multilingual Perspective. AAA: Arbeiten aus Anglistik und Americanistic, 42(2), 189–210.

Schiffrin, D. (1987). Discourse markers. Cambridge University Press.

Schleef, E. (2005). Navigating joint activities in English and German academic discourse: Forms, functions, and sociolinguistic distribution of discourse markers and question tags. [Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation. University of Michigan, MI.].

Schourup, L. (1985). Common discourse particles in English Conversation. Garland.

Sharndama, E. C., & Yakubu, S. (2013). An analysis of discourse markers in academic report writing: Pedagogical implications. International Journal of Academic Research and Reflection, 1/3, 15–24.

Thompson, S. E. (2003). Text-structuring metadiscourse, intonation and the signaling of organization in academic lectures. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 2(1), 5–20.

Thompson, P., & Nesi, H. (2001). Research in progress, the British academic spoken English (BASE) corpus project. Language Teaching Research, 5(3), 263–264. https://doi.org/10.1191/136216801680223443

Townend, J., & Walker, J. (2006). Structure of language: Spoken and written English. Whurr Publishers.

Unger, C. (1996). The scope of discourse connectives: Implications for discourse organization. Povolná, R. (2010). Interactive discourse markers in spoken English. Brno: Masaryk University. Journal of Linguistics, 32, 403–439.

Vande Kopple, W. J. (2012). The importance of studying metadiscourse. Applied Research in English, 1(2), 37–44.

Weydt, H. (2006). What are particles good for? In K. Fischer (Ed.), Approaches to discourse particles (pp. 13–39). Elsevier.

Williams, J. (1981). Style: Ten lessons in clarity and grace (3rd ed.). Scott Foresman.

Zanettin, F., Bernardini, S., & Stewart, D. (2003). Corpora in translator education. St Jerome Pub.

Zarei, G., & Mansoori, S. (2007). Metadiscourse in academic Prose: A contrastive analysis of English and Persian research articles. The Asian ESP Journal, 3(2), 24–40.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Farahani, M.V., Ghane, Z. Unpacking the function(s) of discourse markers in academic spoken English: a corpus-based study. AJLL 45, 49–70 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44020-022-00005-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44020-022-00005-3