Abstract

There is a growing feeling that artificial intelligence (AI) is getting out of control. Many AI experts worldwide stress that great care must be taken on the so-called alignment problem, broadly understood as the challenge of developing AIs whose actions are in line with human values and goals. The story goes that ever more powerful AI systems are escaping human control and might soon operate in a manner that is no longer guided by human purposes. This is what we call the AI-out-of-control discourse which, in this paper, we critically examine and debunk. Drawing on complementary insights from political theory, socio-technical studies and Marxian political economy, we critique the supposed animistic and autonomous nature of AI, and the myth of the uncontrollability of AI. The problem is not that humanity has lost control over AI, but that only a minority of powerful stakeholders are controlling its creation and diffusion, through politically undemocratic processes of decision-making. In these terms, we reframe the alignment problem thesis with an emphasis on citizen engagement and public political participation. We shed light on the existing politics of AI and contemplate alternative political expressions whereby citizens steer AI development or stop it in the first place.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction: AI out of control?

Recently, there seems to be a growing feeling that the development of artificial intelligence (AI) is getting out of control. Such concern has escalated with the release of ChatGPT-4 and it can be observed by looking at three dimensions. First, the public. As of this writing, ChatGPT-4 has over 150 million users and many of them, according to recent studies, seem to believe that this AI has unprecedented human-like properties [1]. This is one of the most powerful AIs ever built, which has entered the mundane spaces of everyday life, with people now able to have conversations with a digital intelligence from the comfort of their homes [2]. Second, the computer scientists and engineers who are building AIs. Emblematic is the paper published by a Microsoft team in which the authors argue that GPT-4 exhibits remarkable capabilities that are strikingly close to human-level performance, thereby showing early signs of general intelligence [3]. They also warn us about the risks of this AI technology, stressing that ‘great care would have to be taken on alignment and safety’ [3 p.2]. Third, there are AI experts worldwide who are monitoring the development of AI and expressing concern over the rapid pace of its innovation. Here the most prominent example, which we use in this paper to critically discuss the seemingly out-of-control nature of AI development, is the Future of Life Institute’s (FLI) open letter published in March 2023.

The letter in question was written and then endorsed by prominent AI scientists and public intellectuals such as Max Tegmark, Stuart Russell and Yuval Noah Harari, asking all AI companies to pause the development of AI systems with a computational power akin or superior to that of GPT-4 for six months [4]. Moreover, the letter calls on governments from all around the world to impose a moratorium on AI development should AI companies like OpenAI and Google keep operating business as usual. Together with its compendium, a longer policy brief [5], the FLI letter offers very useful materials to understand the seemingly general feeling that the development of AI is getting out of control, why this is happening and, above all, what the biggest risks are according to what we refer to as the AI-out-of-control discourse.

The FLI letter notes that ‘recent months have seen AI labs locked in an out-of-control race to develop and deploy ever more powerful digital minds that no one – not even their creators – can understand, predict or reliably control’ [4 p.1]. They describe a type of technological development that has gotten out of control in terms of both pace and outcomes. Among the key risks that the authors of the letter highlight are the creation of ‘non-human minds that might eventually outnumber, outsmart, obsolete and replace us’, and ‘the loss of control of our civilization’ [4 p.1]. Here the meaning is not simply that the development of AI technology is getting out of control, but that AI itself as a non-human mind might soon get out of control and operate in manners that go against human values, interests and goals. In relation to emerging AI systems akin to GPT-4, the letter’s compendium states that ‘the systems could themselves pursue goals, either human or self-assigned, in ways that place negligible value on human rights, human safety or, in the most harrowing scenarios, human existence’ [4 p.4]. In this regard, one of their policy recommendations is ‘a significant increase in public funding for technical AI safety research in […] alignment: development of technical mechanisms for ensuring AI systems learn and perform in accordance with intended expectations, intentions and values’ so that they are ‘aligned with human values and intentions’ [4 p.11].

Essentially, what the FLI is talking about is the so-called alignment problem. This has been confirmed by Max Tegmark (founder of the FLI) in an interview that he gave to announce and discuss the FLI open letter and the proposed pause and moratorium on AI development. He said: ‘The AI alignment problem is the most important problem for humanity to ever solve’ [6]. In this paper we take a different stance. Using the FLI open letter as an entry point, our aim is to critically examine the alignment problem thesis, expose some of the main conceptual flaws that undermine its understanding, and propose an alternative thesis on the way contemporary AI technologies are aligned. We argue that, as it is currently formulated in mainstream public discourses, the alignment problem presents several conceptual issues that are problematic not simply from a theoretical perspective. The alignment problem has also policy implications that are influencing the development of AI technologies in a way that fails to recognize important political aspects.

Our critique proceeds in five steps. First, we present the AI alignment problem thesis as it is generally understood particularly in the fields of computer science and philosophy. Second, we review the academic literature within which this contribution is situated, with a focus on socio-technical approaches to the study of AI. Third, we introduce three fundamental misconceptions that undermine the understanding of the alignment problem as it is currently formulated in line with the FLI open letter. These are the idea that AI has the capacity to act on its own volition, the belief that AI development is getting out of control, and the assumption that these are technical and philosophical issues that can be fixed by improving the technology and philosophy underpinning AI innovation. Fourth, we unpack each misconception in an attempt to explain what is causing it. More specifically, we analyze the animistic tendency that people have had particularly since the Industrial Revolution toward new technologies, intended as the belief that lifelike properties such as will and consciousness can be found in machines. We explain this attitude in the age of AI as a “shortcut” that people resort to, in order to make sense of an otherwise unintelligible technology; with the average user more willing to project consciousness on a complex technology such as ChatGPT-4 than to study its algorithms. Then, we draw on the work of Langton Winner and Karl Marx to debunk the myth of the uncontrollability of AI technology; we do so conceptually by building upon complementary insights from political theory and political economy, and empirically through the support of real-life examples showing how across different scales (countries, regions and cities) there are specific actors who are steering the development of AI. Subsequently, we expose the limits of computer science and philosophy when it comes to understanding and solving the political side of the alignment problem; that is the hidden network of stakeholders behind the production of AI. Finally, we reframe the alignment problem thesis with an emphasis on questions of citizen participation and public political engagement, and define key areas for future research.

Overall, as in this paper we are adopting a theoretical approach, our contribution is theoretical in nature and made of two parts. It expands and updates critical political theory on the alleged uncontrollability and autonomy of technology, in light of the recent concerns raised by AI development. It also fleshes out theoretically the AI alignment problem thesis and contributes to its understanding by adding a hitherto missing Marxian socio-technical perspective.

2 Socio-technical perspectives on AI: a review of the literature

This study is informed by and situated within an emerging socio-technical approach to the analysis of the development of AI. At the core of this approach is the awareness of a profound ‘interaction of social and technical processes’ in the production of AI [7 p. 180]. Drawing on Latour, Venturini reminds us how ‘the evolution of humans and technologies is a chronicle of mutual entanglement and escalating interdependence’ which we can now observe in the way AI technologies are being generated as part of broader socio-political systems [8 p. 107]. There are many examples of interactions between social forces and technological components in the genesis and operation of AI. Pasquinelli, for instance, points out that AI technologies learn by absorbing data that are labelled by humans [9]. Much of this learning process, so-called machine learning, takes place in the human (and hence social) environment par excellence: the city [10]. This is where multiple AIs assimilate vast volumes of data by observing human behavior in practice [2]. In so doing, AIs populate urban spaces and influence the composition of the city itself which is evolving into a complex socio-technical system made of both human and artificial intelligences [11, 12].

Recent socio-technical approaches to the study of AI also remind us that this is a technology that is ultimately experienced by humans whose feelings toward its potential benefits and harms influence how it spreads across society [13]. Moreover, ‘people’s attitudes and perceptions are crucial in the formation and reproduction of the socio-technical imaginaries that sustain technological development’ in the field of AI [14 p. 455]. In these terms, in line with Jasanoff’s theory, human feelings contribute to the development of visions of desirable (or undesirable) futures animated by social expectations of technology, which in turn steer the course of technological development [15].

This approach then recognizes human responsibility in the trajectory and speed of AI development, which is particularly relevant in the context of this critical study on the alignment problem and what we referred to in the introduction as the AI-out-of-control discourse. Korinek and Balwit, for example, frame the alignment problem as a social problem, by taking into account the welfare of the plethora of individuals affected by AI systems, as well as the many stakeholders who actively govern their technological development [16]. Similarly, from a politico-economic perspective, Dafoe stresses how the production of AI is controlled by countries and multinationals seeking to seize economic benefits [17]. We adopt a similar approach and draw on Marxian political economy to contribute to the emerging socio-technical literature on AI and its development. As Pasquinelli remarks, back in the 19th century Marx had already understood that ‘the machine is a social relation, not a thing’ and, in this sense, he can be considered a precursor of the socio-technical approach reviewed in this section. [18 p. 119]. Marx’s theory of political economy has not been mobilized yet, together with more recent socio-technical perspectives, to critique the mainstream understanding of the alignment problem and identify its adverse policy implications, and this is precisely the gap in knowledge where the following contribution is situated.

3 The alignment problem

The so-called alignment problem is part of a complex and multifaceted debate that extends well beyond academia and encompasses industry, policy and news media too [19]. This is an ongoing and rapidly evolving debate to which many heterogeneous voices, ranging from AI experts to public intellectuals, are contributing and, as such, it cannot be confined to one single expression. As the purpose of this paper is to critically examine the AI-out-of-control discourse expressed prominently by the FLI open letter discussed in the introduction, in this section we begin by explaining the nature of the alignment problem as it is understood by the FLI and those who adhere to its stance. Step by step, we will then expose the limitations of the FLI’s view on the alignment problem and integrate alternative perspectives, in order to present a more balanced view on the alignment of AI development.

Through the perspective of the FLI open letter, the alignment problem refers mainly to the challenge of developing AIs whose actions are in line with human values and goals [20,21,22]. This is described and presented as a problem because, for scholars such as Yudkowsky [23] and Bostrom [24], there is no guarantee that powerful AI systems (especially hypothetical superintelligent and conscious ones) will act in a way that is compatible with human values and with the preservation of humanity itself. Bostrom [24] explains this philosophically through the Orthogonality thesis pointing out that intelligence and goals are two orthogonal axes moving along different directions. He concludes that any type of intelligence can in principle follow any type of goal, and that it would be thus safe to assume that a non-human superintelligence might not necessarily follow a humanistic goal [24].

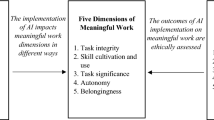

In turn, Bostrom’s reflections have led computer scientists like Russell [25] and Hendrycks et al. [26] to conclude that it is vital to build human-compatible AIs. In practice, as Gabriel [27] explains, solving the alignment problem has two components, each one encapsulating a set of different but interrelated tasks. The first one is technical in nature and is about formally encoding human values in AI [27]. This is essentially a computer science challenge consisting in building an ethical understanding of what is good or bad, right or wrong, directly into the algorithms that steer the actions of a given AI [25]. The second one is philosophical in nature and is about determining what is good and what is bad in the first place, and choosing what specific values will be integrated into AI [27, 28].

This is not the place to discuss the practicalities of the alignment problem in-depth, but it is worth mentioning that both components are intrinsically connected to each other, and that over the years have led to interdisciplinary collaborations between computer scientists and ethicists. In this respect, Gabriel’s example is emblematic given that he is a philosopher working for DeepMind i.e. Google. In addition, each individual component is per se hyper complex. The first one is a matter of how AI learns, which makes it a machine learning issue. In his overview of the technical challenge underpinning the alignment problem, Gabriel [27] notes how there are different machine learning approaches ranging from supervised learning to unsupervised learning, and more experimental techniques such as inverse reinforcement learning whereby AI is not implanted with objectives, but instead ‘can learn more about human preferences from the observation of human behavior’ [29 p.8].

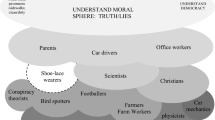

There is still no consensus in the computer science community over what the best approach is. As for the philosophical problem, it is important to remember that ethics has been changing and varying for centuries across spaces and times, and moral dilemmas over what is good or bad in the age of AI abound. For instance, what the right conduct should be for AIs that are already present in our society, such as autonomous cars, is a controversial research topic that shows a considerable degree of dissensus within both academia and the public [30,31,32]. Above all, it is important to remember that there is a lack of consensus regarding the nature of the alignment problem itself and its very premises. For example, the theories of Yudkowsky [23] and Bostrom [24] concerning the hypothetical emergence of superintelligences have been critiqued and dismissed by other voices in the debate, as sci-fi distractions that risk hindering our focus on already existing problems [33, 34].

Similarly, critical social scientists have stressed that AI does not need to be superintelligent to cause harm and that contemporary narrow AIs are already responsible for causing social injustice and environmental degradation [35, 36]. These are AIs whose detrimental actions are not based on malign intents since, as it has been repeatedly stressed in critical AI studies, artificial intelligences are amoral entities that are indifferent to questions of right or wrong [35]. In these terms, the critical side of the debate on the alignment problem ascribes responsibility to the many human stakeholders who shape the development of AI and, therefore, its outcomes. This is why, according to Korinek and Balwit, governance is a key component to the resolution of the alignment problem which then emergences as a social problem, rather than a solely technical and philosophical challenge [16]. It is in line with these critical perspectives, that we now turn to the FLI’s stance and expose its limitations in an attempt to contribute to a more comprehensive and balanced understanding of the alignment problem.

4 Conceptual misunderstandings of the alignment problem

The alignment problem, as it is understood by the FLI and recognized by scholars in favor of its open letter, presents some critical and interrelated issues in the way the problem is conceptualized, which then risk generating practical repercussions in terms of policy. Conceptual issues can undermine how we come to understand the alignment problem as such, and what in theory is causing it. This is crucial and worth examining because conceptual misunderstandings can severely undermine all the actions and policies that are supposed to mitigate or fix the alignment problem. In essence, if we fail to properly understand a problem, any solution that we conceive becomes useless.

We argue that there are currently three main conceptual issues affecting the mainstream understanding of the AI alignment problem, promoted by the FLI:

-

1.

The idea of AI as agentic; meaning a non-human intelligence that has the capacity to act by drawing upon a force of its own, in a way that risks being not aligned with the goals and interests of humanity. Such misunderstanding erroneously pictures humans out-of-the-loop and autonomous AIs in pursuit of non-human objectives.

-

2.

The perception that the development of powerful AIs and the outcomes of their actions are getting out of control. This is the essence of the AI-out-of-control discourse that we mentioned in introduction, according to which AI development has rapidly become unmanageable in the sense that humans are neither capable to stop it, nor able to direct it towards a scenario where AI does exactly what we want it to do. This misunderstanding erroneously depicts AIs that are no longer guided by human purposes.

-

3.

The belief that this is a technical and philosophical problem. This misunderstanding erroneously presents a problem that can be solved by means of better algorithms that make AI act exactly the way we want it to act, according to ethical ideals of what is good or bad defined by philosophers.

Such ideas, beliefs and perceptions present some fundamental misconceptions that it is important and urgent to shed light on. There is indeed an alignment problem but, as we will see in the remainder of the paper, it is much more complex than how the FLI and its open letter are depicting it. The FLI’s stance on the alignment problem is not complete and misses crucial social and political aspects that we aim to identify and discuss, in order to add to the debate. Next, we are going to critically examine each of the conceptual issues introduced above, by drawing upon a combination of insights from political theory, socio-technical literature, and Marxian political economy.

5 First conceptual issue: the supposed animus of AI

The idea of technology as an agentic entity capable of drawing upon a force of its own to act and influence the surrounding physical and social environment, is not new. This is a recurring idea that tends to appear again and again at the dawn of major technological revolutions that spawn machines presenting unprecedented capabilities and functions. One of the main examples of this phenomenon in modern history is Marx’s account in the 1800s of the new technologies of the Industrial Revolution, in which we can find clear signs of animism. This is the belief that lifelike properties can be found beyond the human realm and that objects, for instance, including human-made technologies can be animated and alive, thus exhibiting consciousness and possessing the capacity to act according to intentions of their own.

An animistic line of thought posits that animated object can be benign or malign in the way they engage with the human population. In Das Kapital (1867), Marx takes a negative stance toward the animus driving the actions and outcomes of the technologies of the Industrial Revolution. He depicts the 1800s factory and its technological apparatus as a gigantic entity animated by ‘demonic power’, pulsing with engines described as ‘organs’ and acting by means of ‘limbs’ that extend endlessly like mechanical tentacles [37 p.416]. His account draws upon a complex techno-gothic imaginary merging then popular gothic novels, including the work of John William Polidori and Mary Shelley, with the technological innovations of the 19th century, through which technology is at times portrayed like a vampire that drains the life and soul of the workers who are creating it [38].

Similar traces of animism can be found during another major technological revolution: the development of home computers in the 1970s and their diffusion in the 1980s. This becomes particularly evident in the mid 1980s when computer technology begun to be widely popularized through personal computers (PC). It is through the PC that a number of people started to interact with then new computer technologies, finding themselves in the position of having to make sense of this type of technology. As Stahl [39] observes, in the 1980s discourses surrounding personal computers do not simply refer to technology as an object. For him, the discourse in question has a quasi-magical tone and describes computers as machines possessing intelligence and capable of talking and acting [39]. He notes that back then ‘the machine was frequently portrayed as the active partner’ in the emerging relationships between humans and computers whom ‘were spoken of in the active voice, as if they had volition’ [39 p.246].

Volition is the act of making a conscious choice. It implies having intentions, will and other life-like properties that we commonly associate with humanity rather than machinery. But in the 1980s this conceptual association was being reshaped by new cultural perceptions of technology. When Marx was writing about the technologies of the 19th century, the zeitgeist was characterized (particularly in the West) by a techno-gothic imaginary whereby the properties of the new machines of the industrial age were being interpreted through the lens of monstrous myths. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s instead, we find an emerging sci-fi imaginary promoted by authors such as Isaac Asimov and William Gibson, that introduced to the public the idea of intelligent machines and cultivated the early fantasies about AI [40]. It is not a coincidence that, around the same time, we have important sociological studies, notably the work of Sherry Turkle [41], showing that some people were under the impression that computers were intelligent and alive.

The same animistic thread remerges in our contemporary society, starting from the 2010s when relatively powerful AIs begin to enter domestic spaces and everyday life, thereby interacting with a growing number of people. A prominent example of this phenomenon is Siri launched in 2011 by Apple. This is a powerful AI in the sense that it can engage in basic forms of conversation and mediate several activities. It is a step forward compared to the PCs of the 1980s not simply in terms of computational capacity, but also because of how pervasive the technology is. This is a technology that like Amazon’s Alexa is meant to penetrate into people’s private spaces and life; its designed personality seemingly human-like expressed through names, gender and a feminine tone of voice [42].

For scholars such as Marenko [43 p.221], AIs like Siri are triggering a new wave of animism, a digital neo-animism, as ‘we often end up treating our smartphone as if it is alive.’ In these terms, neo-animism is understood as the contemporary belief that novel AI technologies possess lifelike properties such as will, intentionality and consciousness [43]. Within this strand of literature, the perception of emerging AIs is that of actants which animate our everyday spaces and objects, and ultimately influence our life [44]. In reality, as we have seen in the first part of this section, there is nothing new about such animistic response to new technologies. Today the response is essentially the same that Marx [37] gave in the 1800s and that Stahl [39] reports in the 1980s. The nature of technology has considerably changed, but people’s reaction has not: we find an analogous animistic tendency that portrays a given new technology as an agentic entity capable of acting upon a force and intention of its own. There is thus a long-standing connection between animism and the idea of agentic technologies, which cuts across the last two centuries of the history of technology and our social attitudes toward it.

From the industrial machines of the 1800s to the PCs of the 1980s and, more recently, in relation to the many AIs that permeate our daily life we find the same animistic common denominator. To dig deeper into the subject matter, we need to ask the following questions: Why is this happening? Why does this keep happening through the ages? Why do we develop these animistic tendencies toward new technologies? The answers lie in the longstanding habit of human users to ‘project agency, feelings and creativity onto machines’ [45 p.2]. This is animism in action, whereby an inanimate technology, nowadays AI, is perceived as an agentic entity. According to Marenko and Van Allen [44 p.54], ‘users tend to attribute personality, agency and intentionality to devices because it is the easiest route to explain behavior.’ In these terms, it is easier to believe that a machine has an animus, than to comprehend the complex mechanisms that make it work in a certain way. Following this line of thought and applying it to the recent wave of AI technologies that is investing our society, we can posit that it is easier to believe that Alexa has a personality or that ChatGPT exhibits some degree of consciousness, compared to how incredibly difficult it would be for most people to study the algorithms whereby these AIs perceive reality and act on it. Animism becomes then a “shortcut” to make sense of AI’s behavior, by assuming that this is an agentic technology possessing lifelike properties, such as consciousness and volition, instead of making an effort to understand the algorithms that make AI behaves in a certain way.

In addition, there is another common denominator underpinning the various waves of animism discussed in this section, and that is the occult of new technologies. A new technology tends to be occult in the sense that its functioning is often beyond the realm of human comprehension, apart from a small group of initiates: those who are building and studying the technology in question. This was true in the 1800s when anyone without a working knowledge of engineering could barely comprehend how then new engines were functioning and why mechanical devices seemed to move on their own. The same was true in the 1980s when most people without a background in computer science could not understand the software that was making PCs work. This is even truer today when the very computer scientists and engineers who are designing and building Large Language Models (LLMs) such as GPT-4 do not fully understand their own creations. As computer scientist Sam Bowman remarks, ‘any attempt at a precise explanation of an LLM’s behavior is doomed to be too complex for any human to understand’ given the countless connections among artificial neurons at play in the production of just one piece of text [46].

As Greenfield [47] puts it, AI is an arcane technology that tends to escape human comprehension. Recent empirical research suggests that, around the world, levels of so-called AI literacy, which is the ability to understand and use AI technologies, are low and many users exhibit ‘the tendency to attribute human-like characteristics or attributes to AI systems’ [48 p.5]. This problematic epistemological aspect has been repeatedly stressed in Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) literature where AI is often portrayed as a black box intended as a device whose inner workings are extremely difficult to understand [49,50,51]. However, while the black box narrative is getting very popular nowadays to highlight the scarce intelligibility of AI systems, it is far from being new. Black box is the same exact term that Stahl [39] employed to unpack the animistic and quasi-magical attitudes that people had in the 1980s toward PCs. As he observed back then: ‘Computers were powerful, but also mysterious. Their power was ours to use, but not to understand. When technology is a black box, it becomes magical’ [39 p.252].

6 Second conceptual issue: the myth of the uncontrollability of AI

The first conceptual issue is connected to the second one: the belief that the development of AI is getting out of control. As Nyholm [52] notes, ‘whenever there is talk about any form of AI or new technologies more generally, worries about control tend to come up.’ In essence, this is the worry that we humans are unable to safely manage (let alone stop) the creation and diffusion of ever more powerful AIs that appear to be acting upon their own volition. In the previous section, we have critically discussed the animistic notion of technology as a human tendency to project personality and consciousness on new technologies, and to believe that such technologies have volition and can make conscious choices. As we have seen, this is a tendency that becomes evident from the Industrial Revolution onwards and that is triggered by humans’ incapacity to understand how a device showing unprecedented capabilities (being it a 1800s engine or a 21st century Large Language Model such as GPT-4) actually works.

In this section, we tackle the conceptual issue of AI as a technology that seems to be getting out of control. That of technology out of control is a recurring theme in the work of political theorist Langton Winner who has contributed to the development of a critical political theory of technology with his notion of autonomous technology. His is one the initial attempts to develop a socio-technical perspective on the study of technology, in a way that recognizes human responsibility in the trajectory of technological development. According to Winner [53 pp.13–15], ‘the idea of autonomous technology’ is ‘the belief that somehow technology has gotten out of control and follows its own course.’ For him [ibid], a technology out of control is one that is running amok ‘and is no longer guided by human purposes’ or controlled by human agency. As we can see from this passage, Winner himself talks about the phenomenon of technology out of control not as a fact, but as a belief. This is a belief that he questions, trying to understand why for a very long time (but particularly in modern and contemporary history) many people seem to believe that the development of technology and its outcomes have gotten out of control.

In his explanation, Winner stresses one issue in particular: speed. He reflects on the velocity of technological innovation, remarking how quickly ‘technology-associated alterations take place’ [53 p.89]. In addition, he notes that many of the changes triggered by technological development are usually unintended, concluding that ‘technology always does more than we intend’ [53 p.98]. We can build on Winner’s reflections and add that technology-associated alterations that are unintended tend to be also unexpected. While a major technological development triggers changes and leads to outcomes that were unintended, it naturally finds many people unprepared since much of those changes and outcomes were not expected. Referring back to the examples and historical periods discussed in the previous section, we know for instance that some of the major changes and outcomes produced by the Industrial Revolution were both unintended and unexpected, at least for most of the population. The increase in productivity enabled by the new machines of the 19th century were indeed intended and expected [54]. However, the negative environmental changes (heavy pollution and destruction of natural habitat, in particular) that were triggered by the extraction and consumption of the resources necessary to build and power 1800s machines were not. Nor were the radical socio-economic and geographical transformations associated with the technological innovation of that period. This includes the rapid growth of large and polluted industrial cities and the process of suburbanization whereby the rich were trying to escape from the smokes of industry [55, 56]. Not to mention the historical records indicating a significant increase in infectious diseases, alcoholism, domestic violence and, thus, death rates in the large and overcrowded cities of the Industrial Revolution [54, 57].

If you were experiencing similar changes (substantial in nature and taking place at a fast pace) it would be easy to feel in a position of no control over technological development. When the production of new technology leads to outcomes that were unintended, unexpected and alter the surrounding social and physical environment, in the words of Winner [53 pp.89, 97] ‘we find ourselves both surprised and impotent – victims of technological drift’ with ‘societies going adrift in a vast sea of unintended consequences’ triggered by technological innovation. However, this is partly an illusion. As Winner [53 p.53] notes, ‘behind modernization are always the modernizers; behind industrialization, the industrialists.’ The reality then is not that we have lost control of technological development: some of us are in control, and this is usually a minority of powerful individuals who make conscious and deliberate decisions that shape the direction and outcomes of technological innovation. There are thus potent socio-political forces that steer the trajectory of the development of technology, but these are associated with a type of power (the power to shape technological innovation) that is unevenly distributed across society.

Winner [53 p.53] is adamant in affirming that ‘the notion that people have lost any of their ability to make choices or exercise control over the course of technological change is unthinkable; for behind the massive process of transformation one always finds a realm of human motives and conscious decisions in which actors at various levels determine which kinds of apparatus, technique, and organizations are going to be developed and applied.’ The problem in contemporary discourses about technological development is the use of general terms such as people and society, implying (like in the case of the FLI open letter) that the whole humanity has lost control over the development of AI technology. Winner’s studies remind us that there are always specific actors making choices that determine the nature, scope and place of technology.

This is the same conclusion that Marx had reached upon reflecting on the origin of 19th century technologies. Despite the animistic passages in Das Kapital quoted in the previous section, Marx was well aware of the fact that the new technologies that he was observing were neither animated nor spawn by demonic forces. There was human agency behind them or, in the words of Marx [37 p.462], a ‘master’ who was consciously deploying technology to fulfil specific agendas driven by the will to accumulate capital to the detriment of both laborers and the environment. In essence, the work of Winner and Marx is useful to remember that we can always find someone who is to some extent in control of technological development. Technological innovation is not a process bereft of human intervention. Quite the opposite: it is a human strategy whereby a powerful minority of individuals attempt to get hold of the production of new technology to achieve their own goals. There are plenty of historical examples of such power dynamics as they intersect with and alter technological development, ranging from the development of railways championed by George Stephenson in Victorian England to the mechanization of Soviet agriculture led by Joseph Stalin in the early 1930s [54]. The problem is that, in the present, we do not see these individuals. We do not see them acting and making choices that shape technological development. What we do see are the technologies that are being produced and the changes that they cause, altering society and the environment at a fast pace.

This problem is connected to the black box problem discussed above. In a way it is an extension of the black box, which is worth unpacking in an attempt to get a glimpse of the big picture. New technologies can be understood as a black box, whether it is a 1980s PC [39] or a 2020s AI [51], because their mechanics and functioning remain obscure to their users who ignore their impenetrable operations. However, users also do not see the political economy underpinning the production of new technology, which remains more obscure and inscrutable than the inner mechanics of the technology itself. In other words, most people are unaware of the many political agendas and decisions that set the direction of economic development at different scales (companies, cities, regions and states, for example), which in turn dictate what new technologies will be produced, where and how. Of course, some people do manage to see these intricate politico-economic dynamics, but achieving such awareness requires a considerable effort in terms of research and critical thinking, since this aspect of technological innovation cannot be found at the surface level. A case in point is Marx who was capable of identifying the hand and the mind of the capitalist behind the rapid diffusion of seemingly out-of-control technologies in 19th century England, because he had extensively studied 19th century English political economy. He was fully aware of the big picture. He had penetrated the black box.

More recently, critical social scientists are beginning to shed light on the actors that today are steering the development of AI, and in so doing, triggering significant social and environmental transformations [58, 59]. Penetrating the black box means shedding light not simply on the technical aspects of new technologies to understand what makes them function the way they do (whether it is a steam engine in 19th century machines, or software in 1980s PCs, or algorithms in contemporary AIs). It also means exposing the complex political economy that drives the production of new technologies and render visible the network of stakeholders who, guided by human purposes, make choices in an attempt to control the course of technological development and its outcomes. Some of these choices include speed. It would be erroneous to think that technological development proceeds at a faster and faster pace, gaining momentum autonomously like a rock that rolls down a hill and continues moving because of its inertia. The pace of technological development is based on conscious decisions that specific actors make to accelerate its course, in line with pre-determined politico-economic rationales according to which a rapid roll-out of new technologies is expected to accrue certain benefits. The development of new technology might have some degree of inertia but, for the most part, it is tenaciously pushed forward by human hands under the guidance of human logics. Historically, a case in point is that of the Ford Motor Company and its iconic car, the model T, developed in 1908, just five years after the establishment of Ford’s company [54]. Back then, as Henry Ford himself acknowledged, ‘speed’ was one of the key principles that his company was actively adhering to, implementing ‘high-speed tools’ and perfecting the factory’s assembly line to purposely speed up the production of cars as much as possible [60 p.143, 61 p.2170].

In relation to contemporary AI technologies, the phenomenon that has been described so far in conceptual terms, can be also observed in practice across three different scales: country, region and city. The aim here is not to provide an in-depth empirical analysis of how specific actors attempt to take control over AI innovation, but rather to offer an overview of such dynamics and of the logics underpinning them. At the first scale, within many countries, we find national AI strategies. Bareis and Katzenbach [62], for example, have analyzed the national AI strategies of four key players in the field of AI development, namely China, the United States, Germany and France. In their analysis, they note how ‘the role of the state remains crucial’ as it is in national AI strategies that ‘ideas, announcements and visions start to materialize in projects, infrastructures and organizations’ [62 pp.859, 875]. As part of a national AI strategy there are also national research grants through which states finance AI research, thereby boosting AI development, as well as trade sanctions meant to hinder AI development in other states, such as the recent American restrictions on the export of chips to China [58]. These are important dynamics to highlight because a strategy is a plan of action intended to accomplish specific goals. National AI strategies, therefore, show that AI development is not following its own course independent of human direction. These are evident state-led attempts to capture and steer AI development. In this context, as Bareis and Katzenbach [62 p.875] point out, governments explicitly ‘claim agency’ in the production of AI technologies.

At the scale of the region, the dynamics illustrated above become even more evident as the more we zoom in on specific places, the more the agency of specific actors emerges. An emblematic case of regional AI development is Neom in Saudi Arabia. Neom [63] is a megaproject consisting in the creation of new cities and infrastructures in the north-west of the Arabian Peninsula. The Neom development which includes a new linear city called The Line [64] has AI as its common denominator, the plan being that all services and infrastructures will be automated by means of algorithms and robotics, and that robots will hold citizenship and coexist with humans in the same urban spaces [65]. The plan in question is the product of one actor in particular: Mohamed bin Salman (MBS) Crown Prince of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and Chairman of Neom. There is a specific rationale behind the production of Neom and its technological apparatus. The power of MBS in Saudi Arabia is growing, but the ambitious Crown Prince is relatively young and has a lot of opponents who resent his autocracy [66]. In this politically unstable context, MBS is seeking to crystallize his position as the sole leader of the Kingdom by investing in megaprojects like Neom, in a bet to boost both his prestige and economic assets. As Hope and Schek [67] observe, MBS is purposely accelerating the speed of technological development in order to consolidate his power as soon as possible and take his adversaries by surprise. This is a clear example of how the rapid pace of AI innovation does not depend on the inertia of out-of-control technologies, but on the agency of specific individuals.

Finally, when we look at cities, we can identify a fine-grained network of actors who join forces to steer the development of AI in urban spaces. The work of Zhang, Bates and Abbott [68], for instance, reveals the variegated groups of stakeholders behind smart-city initiatives in China, whereby multiple AI technologies are developed and integrated into the built environment. Recent smart-city studies focused on AI show how the genesis and diffusion of AI technology are often the product of the cooperation between public stakeholders (city councils, planning departments and city managers) and private stakeholders (tech companies, in particular) that have different stakes and pursue different but compatible goals [2]. As Lee [69] explains, Chinese tech companies need to push AI innovation forward as for them innovation is the only way to survive in a very competitive and ruthless market. In the same context, city councils tend to follow regional and national strategies of AI development set by China’s State Council, in a way that problematically excludes citizen engagement and bottom-up inputs from the local population [70]. Referring back to one of the key points made above, the problem is not that humanity has lost control over AI development, but that only a small percentage of it is controlling the creation and diffusion of AI.

7 Third conceptual issue: the overbelief in computer science and philosophy

In addition, the misconceptions that we have discussed so far create a third misunderstanding: the belief that we can regain control over AI by means of better algorithms that compel AI to act exactly the way we want it to act, according to well-defined ethical principles. However, as we have argued in the previous section, we already have control over AI. We humans do not have to gain (or regain) control over artificial intelligences, because we already have it. The problem is that most of us do not have control over AI, and only a minority of powerful stakeholders are controlling and steering the development of AI, often through procedures and decision-making processes that are undemocratic. Therefore, while there is indeed an alignment problem, it is neither a matter of computer science (designing better algorithms), nor simply a matter of philosophy (formulating better ethical principles). The question is political.

It is no mystery that there is a politics to AI [71,72,73]. Contrary to what animistic interpretations of AI might suggest, there is no magic in AI. What we are witnessing is not a magic show, but rather a game of politics that a Marxian politico-economic perspective can help us comprehend. In these terms, the AI ethics industry which has been producing a voluminous corpus of ethical guidelines regarding the creation and deployment of AI technology, is not helping us to overcome the impasse discussed in this section. This is a diverse sector comprising a variety of voices, ranging from international organizations and corporations to business consultancies and independent ethicists [74]. Yet, apart from few critical voices, there is a problematic common denominator [75]. By and large, this sector is not opposing the diffusion of AI, proposing instead top-down technical and philosophical solutions which, by targeting the development of ethically sound algorithms and refined ethical codes, fail to engage with citizens who are ultimately marginalized in the politics of AI. A significant portion of contemporary AI ethics is thus part of the same political economy that we have critiqued so far and risks causing ‘ethics shopping’ whereby some ‘stakeholders may be tempted to “shop” for the most appealing’ ethical principles and ignore the issue of citizen engagement to which we now turn [75 p.390, 76 p.2].

8 Reframing the alignment problem thesis from a Marxian perspective

In relation to the alignment problem discussed so far, a Marxian perspective is useful to note that much of the labor involved in the production of AI is problematically not involved in steering the course of its development. In this context, labor includes for example the myriad ghost workers who are underpaid to train AIs, as well as the countless citizens who become data points and get their personal information extracted, mostly via social media, through processes of surveillance capitalism that, as Zuboff remarks, ultimately feed AI systems [77, 78]. There is thus an evident unethical situation of exploitation at play, since many of the people whose labor and data are used to develop AI, are not contributing to the political agendas and decisions that actually shape AI developments.

In Marxian terms then, reframing the alignment problem means acknowledging this problematic political issue, beyond the already recognized technical and philosophical problems that dominate much of current public discourses. In these terms, AI ethics needs to recognize the fundamental presence of humans in the making of AI systems by integrating a socio-technical perspective, and take into serious consideration the uneven power relations that control their development. In theory, this calls for more participation and extended stakeholder engagement in AI ethics. In practice, we envision public engagement, particularly at the smallest scale examined in this paper i.e. the city, in line with two examples. First is the case of Barcelona where citizens’ opinions are increasingly being included in the local AI-driven platform for urban governance, de facto influencing its application and purpose [79]. Second is the case of San Francisco where in 2022 citizens protested against weaponized police robots, and managed to stop their deployment in the city [80]. The first example is a story of democratic political engagement, while the second story is about an agonistic political act carried out by expressing dissensus [81, 82].

9 Conclusions: illuminating the obscure politics of AI

As this paper has shown, there are three fundamental misconceptions about the alignment problem as it is often formulated and understood in mainstream public discourses, such as in the case of the FLI open letter. The first and the second one depict a situation in which AI is acting on its own volition and getting out of control. These two misunderstandings are two sides of the same black box issue discussed throughout the paper. We do not understand the complex machine learning techniques and algorithms whereby AI learns about the surrounding environment and act on it and, therefore, many of us resort to animism as a “shortcut” to explain the behavior of hyper complex and unintelligible AI technologies such as ChatGPT. In addition, we do not understand the complex political economy driving the production of AI technology and we do not see the fine-grained network of actors who, across different scales (countries, regions and cities), make decisions that steer the development of AI. In this regard, we have drawn on the examples of national AI strategies by means of which state-actors explicitly attempt to control the production of AI technologies, of the high-tech Neom project of regional development tightly controlled by the Saudi Crown Prince, and of Chinese smart-city initiatives steered by partnerships between public stakeholders and AI companies.

Failing to comprehend these politico-economic dynamics gives us the illusion that AI innovation occurs at a fast pace propelled by an incontrollable momentum, while speed itself is a conscious strategy implemented by human stakeholders in line with human-made agendas. These two misunderstandings give rise to a third misunderstanding, the belief that computer science and philosophy alone can help us solve the alignment problem and, in turn, invalidate much of the current strategies and policies that are being developed worldwide to realign AI development, such as the moratorium proposed by the FLI in its open letter. AI is neither acting on its own volition nor is it getting out of control. In this paper we have debunked the AI-out-of-control discourse and stressed that AI is controlled by a minority of powerful human stakeholders. This makes the alignment problem not a computer science problem or a philosophical issue, but rather an acute political problem.

The politics of AI is still, by and large, an uncharted and obscure territory that needs to be empirically understood in detail across different scales. As states forge national AI strategies, regions develop AI infrastructures, and cities integrate AI technologies into the built environment, it is key that future research seeks to identify who exactly is controlling the production of AI and how. This is the politico-economic side of the black box that we know is there, but that we have not penetrated yet, by digging into the thick layers of decision-making processes whereby AI innovation takes place. In addition, areas of future research should include public participation in the politics of AI in both theory and practice. Empirically, this means examining in more detail cases, such as those of Barcelona and San Francisco, in which citizens are manifesting different forms of political engagement [79, 80]. Theoretically, this is about drawing on political theory to theorize alternative participatory politics of AI.

In this regard, Mouffe’s theory of agonistic politics and Rancière’s notion of dissensus can be useful to imagine a politics of AI whereby citizens can opt against some types of AI [81, 82]. This would rectify the current imbalance in contemporary AI ethics in which most efforts go into improving the use of AI rather than objecting it in the first place. As this paper has shown from a socio-technical perspective, AI development is not a magic show: it is a game of politics. If we pay attention to the hidden puppeteers, not on the puppet, then we can start realigning the development of AI to common goals, and this could also mean say no to AI and end the game.

References

Ma, X., Huo, Y.: Are users willing to embrace ChatGPT? Exploring the factors on the acceptance of chatbots from the perspective of AIDUA framework. Tech. Soc. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2023.102362

Cugurullo, F., Caprotti, F., Cook, M., Karvonen, A., McGuirk, P., Marvin, S.: Artificial Intelligence and the City: Urbanistic Perspectives on AI. Routledge, London and New York (2023)

Bubeck, S., Chandrasekaran, V., Eldan, R., Gehrke, J., Horvitz, E., Kamar, E., Lee, P.: Sparks of artificial general intelligence: Early experiments with gpt-4. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.12712 (2023)

Future of Life Institute: Pause Giant AI Experiments: An Open Letter. (2023). https://futureoflife.org/open-letter/pause-giant-ai-experiments/ Accessed 23 March 2024

Future of Life Institute: Policymaking in the Pause. (2023). https://futureoflife.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/FLI_Policymaking_In_The_Pause.pdf Accessed 23 March 2024

Fridman, L.: Max Tegmark: The Case for Halting AI Development | Lex Fridman Podcast #371 [2:11:00]. (2023). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VcVfceTsD0A&t=7948s Accessed 23 March 2024

Holton, R., Boyd, R.: Where are the people? What are they doing? Why are they doing it?’(Mindell) situating artificial intelligence within a socio-technical framework. J. Sociol. 57(2), 179–195 (2021)

Venturini, T.: Bruno Latour and Artificial Intelligence. Tecnoscienza–Italian J. Sci. Technol. Stud. 14(2), 101–114 (2023)

Pasquinelli, M.: How a Machine Learns and Fails: A Grammar of Error for Artificial Intelligence. Spheres: Journal for Digital Cultures. 5: 1–17 (2019)

Cugurullo, F., Caprotti, F., Cook, M., Karvonen, A., MGuirk, P., Marvin, S.: The rise of AI Urbanism in post-smart Cities: A Critical Commentary on Urban Artificial Intelligence, vol. 00420980231203386. Urban Studies (2023)

Palmini, O., Cugurullo, F.: Charting AI urbanism: Conceptual sources and spatial implications of urban artificial intelligence. Discover Artif. Intell. 3(1), 15 (2023)

Palmini, O., Cugurullo, F.: Design culture for sustainable urban artificial intelligence: Bruno Latour and the search for a different AI urbanism. Ethics Inf. Technol. 26(1), 11 (2024)

Cugurullo, F., Acheampong, R.A.: Fear of AI: An Inquiry into the Adoption of Autonomous cars in Spite of fear, and a Theoretical Framework for the Study of Artificial Intelligence Technology Acceptance, pp. 1–16. AI & SOCIETY (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01598-6

Sartori, L., Bocca, G.: Minding the gap (s): Public perceptions of AI and socio-technical imaginaries. AI Soc. 38(2), 443–458 (2023)

Jasanoff, S., Kim, S.H.: Dreamscapes of Modernity: Sociotechnical Imaginaries and the Fabrication of Power. University of Chicago Press, Chicago (2015)

Korinek, A., Balwit, A.: Aligned with whom? Direct and social goals for AI systems. National Bureau of Economic Research. (2022). https://www.nber.org/papers/w30017 Accessed 23 March 2024

Dafoe, A.: AI governance: a research agenda. Future of Humanity Institute. (2018). https://www.fhi.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/GovAI-Agenda.pdf Accessed 23 March 2024

Pasquinelli, M.: The eye of the Master: A Social History of Artificial Intelligence. Verso Books, London (2023)

Ji, J., Qiu, T., Chen, B., Zhang, B., Lou, H., Wang, K., Gao, W.: AI alignment: A comprehensive survey. arXiv Preprint (2023). arXiv:2310.19852

Christian, B.: The Alignment Problem: Machine Learning and Human Values. WW Norton & Company, New York (2020)

Erez, F.: Ought we align the values of artificial moral agents? AI Ethics. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-023-00264-x

Friederich, S.: Symbiosis, not alignment, as the goal for liberal democracies in the transition to artificial general intelligence. AI Ethics. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-023-00268-7

Yudkowsky, E.: Artificial intelligence as a positive and negative factor in global risk. In: Bostrom, N., Cirkovic, M.M. (eds.) Global Catastrophic Risks, pp. 308–345. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2008)

Bostrom, N.: Superintelligence. Paths, Dangers, Strategies. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2017)

Russell, S.: Human Compatible: Artificial Intelligence and the Problem of Control. Penguin, London (2019)

Hendrycks, D., Burns, C., Basart, S., Critch, A., Li, J., Song, D., Steinhardt, J.: Aligning AI with shared human values. arXiv preprint arXiv:02275(2020). (2008)

Gabriel, I.: Artificial intelligence, values, and alignment. Minds Mach. 30(3), 411–437 (2020)

McDonald, F.J.: AI, alignment, and the categorical imperative. AI Ethics. 3(1), 337–344 (2023)

Russell, S.: Human-compatible artificial intelligence. In: Muggleton, S., Chater, N. (eds.) Human-Like Machine Intelligence pp, pp. 3–23. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2021)

Cugurullo, F.: Good and evil in the Autonomous City. In: Mackinnon, D., Burns, R., Fast, V. (eds.) Digital (in) Justice in the Smart City pp, pp. 183–194. University of Toronto, Toronto (2022)

Tolmeijer, S., Arpatzoglou, V., Rossetto, L., et al.: Trolleys, crashes, and perception—a survey on how current autonomous vehicles debates invoke problematic expectations. AI Ethics. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-023-00284-7

Othman, K.: Understanding how moral decisions are affected by accidents of autonomous vehicles, prior knowledge, and perspective-taking: A continental analysis of a global survey. AI Ethics. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-023-00310-8

Floridi, L.: Artificial intelligence as a public service: Learning from Amsterdam and Helsinki. Philos. Technol. 33(4), 541–546 (2020)

Cugurullo, F., Caprotti, F., Cook, M., Karvonen, A., McGuirk, P., Marvin, S.: Conclusions: The present of urban AI and the future of cities. In: Cugurullo, F., Caprotti, F., Cook, M., Karvonen, A., McGuirk, P., Marvin, S. (eds.) Artificial Intelligence and the City pp, pp. 361–389. Routledge, London and New York (2023)

Cugurullo, F.: Frankenstein Urbanism: Eco, Smart and Autonomous Cities, Artificial Intelligence and the end of the city. Routledge, London and New York (2021)

Lindgren, S.: Handbook of Critical Studies of Artificial Intelligence. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham (2023)

Marx, K.: Capital: Volume I. Penguin UK, London (2004)

Fromm, E., Marx, K.: Marx’s Concept of Man: Including ‘Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts’. Bloomsbury Publishing, London (2013)

Stahl, W.A.: Venerating the black box: Magic in media discourse on technology. Science, Technology, & Human Values 20, no. 2: 234–258 (1995)

Hermann, I.: Artificial intelligence in fiction: Between narratives and metaphors. AI Soc. 38(1), 319–329 (2023)

Turkle, S.: The Second Self: Computers and the Human Spirit. MIT Press, Cambridge (1984)

Strengers, Y., Kennedy, J.: The Smart wife: Why Siri, Alexa, and Other Smart home Devices need a Feminist Reboot. MIT Press, Cambridge (2021)

Marenko, B.: Neo-animism and design: A new paradigm in object theory. Des. Cult. 6(2), 219–241 (2014)

Marenko, B., Van Allen, P.: Animistic design: How to reimagine digital interaction between the human and the nonhuman. Digit. Creativity. 27(1), 52–70 (2016)

Natale, S., Henrickson, L.: The Lovelace effect: Perceptions of creativity in machines. New. Media Soc. 14614448221077278. (2022)

Bowman, S.R.: Eight Things to Know about Large Language Models. (2023). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2304.00612

Greenfield, A.: Radical Technologies: The Design of Everyday life. Verso Books, London (2017)

Bewersdorff, A., Zhai, X., Roberts, J., Nerdel, C.: Myths, mis-and preconceptions of artificial intelligence: A review of the literature. Computers Education: Artif. Intell. 100143 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2023.100143

de Fine Licht, K., de Fine Licht, J.: Artificial intelligence, transparency, and public decision-making: Why explanations are key when trying to produce perceived legitimacy. AI Soc. 35, 917–926 (2020)

Rai, A.: Explainable AI: From black box to glass box. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 48, 137–141 (2020)

Zednik, C.: Solving the black box problem: A normative framework for explainable artificial intelligence. Philos. Technol. 34(2), 265–288 (2021)

Nyholm, S.: A new control problem? Humanoid robots, artificial intelligence, and the value of control. AI Ethics. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-022-00231-y

Winner, L.: Autonomous Technology: Technics-out-of-control as a Theme in Political Thought. MIT Press, Cambridge (1977)

Johnson, S., Acemoglu, D.: Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity. Basic Books, London (2023)

Benevolo, L.: The European City. Blackwell, Oxford (1993)

Hall, P.: Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design since 1880. Blackwell, Oxford (2002)

Finer, S.E.: The life and Times of Sir Edwin Chadwick. Routledge, London and New York (2016)

Rella, L.: Close to the metal: Towards a material political economy of the epistemology of computation. Soc. Stud. Sci. 54(1), 3–29 (2024)

van der Vlist, F., Helmond, A., Ferrari, F.: Big AI: Cloud infrastructure dependence and the industrialisation of artificial intelligence. Big Data Soc. 11(1) (2024). https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517241232630

Nye, D.E.: Consuming Power: A Social History of American Energies. MIT Press, Cambridge (1999)

Hounshell, D.: From the American System to mass Production, 1800–1932: The Development of Manufacturing Technology in the United States (No. 4). Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore (1984)

Bareis, J., Katzenbach, C.: Talking AI into being: The narratives and imaginaries of national AI strategies and their performative politics. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values. 47(5), 855–881 (2022)

Neom: What is Neom? (2023). https://www.neom.com/en-us Accessed 23 March 2024

Batty, M.: The Linear City: Illustrating the logic of spatial equilibrium. Comput. Urban Sci. 2(1), 8 (2022)

Parviainen, J., Coeckelbergh, C.: The political choreography of the Sophia robot: Beyond robot rights and citizenship to political performances for the social robotics market. AI Soc. 36, 3: 715–724 (2021)

Davidson, C.M.: Mohammed Bin Salman Al Saud: King in all but name. In: Larres, K. (ed.) Dictators and Autocrats: Securing Power Across Global Politics pp, pp. 320–345. Routledge, London PP (2022)

Hope, B., Scheck, J.: Blood and Oil: Mohammed Bin Salman’s Ruthless Quest for Global Power. Hachette UK, London (2020)

Zhang, J., Bates, J., Abbott, P.: State-steered smartmentality in Chinese smart urbanism. Urban Studies 59, 14: 2933–2950. (2022)

Lee, K.: AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the new World Order. Houghton Mifflin, Boston and New York (2018)

Xu, Y., Cugurullo, F., Zhang, H., Gaio, A., Zhang, W.: The Emergence of Artificial Intelligence in Anticipatory Urban Governance: Multi-scalar evidence of China’s transition to City brains. J. Urban Technol. 1–25 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1080/10630732.2023.2292823

Coeckelbergh, M.: The Political Philosophy of AI: An Introduction. Polity, Cambridge (2022)

Crawford, K.: Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. Yale University Press, New Haven (2021)

Kalluri, P.: Don’t ask if artificial intelligence is good or fair, ask how it shifts power. Nature. 583, 7815: 169–169 (2020)

Jobin, A., Ienca, M., Vayena, E.: The global landscape of AI ethics guidelines. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1(9), 389–399 (2019)

Attard-Frost, B., De los Ríos, A., Walters, D.R.: The ethics of AI business practices: A review of 47 AI ethics guidelines. AI Ethics. 3(2), 389–406 (2023)

Floridi, L., Cowls, J.: A unified framework of five principles for AI in society. Harv. Data Sci. Rev. (2019). https://hdsr.mitpress.mit.edu/pub/l0jsh9d1/release/8

Gabrys, J.: Programming environments: Environmentality and citizen sensing in the smart city. Environ. Plann. D: Soc. Space. 32(1), 30–48 (2014)

Zuboff, S.: The age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the new Frontier of Power. Profile books, London (2019)

Cardullo, P., Ribera-Fumaz, R., González Gil, P.: The Decidim ‘soft infrastructure’: democratic platforms and technological autonomy in Barcelona. Computational Culture, (9). (2023). http://computationalculture.net/the-decidim-soft-infrastructure/ Accessed 23 March 2024

Blanchard, A.: Autonomous force beyond armed conflict. Mind. Mach. 33(1), 251–260 (2023)

Mouffe, C.: Agonistics: Thinking the World Politically. Verso Books, London (2013)

Rancière, J.: Disagreement: Politics and Philosophy. University of Minnesota, Minneapolis (1999)

Acknowledgements

Intellectually this paper benefitted enormously from the comments of four anonymous reviewers, and financially from the support of the Irish Research Council.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium. https://doi.org/10.13039/501100002081 Irish Research Council, IRCLA/2022/3832. Prof. Federico Cugurullo https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0625-8868.

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cugurullo, F. The obscure politics of artificial intelligence: a Marxian socio-technical critique of the AI alignment problem thesis. AI Ethics (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-024-00476-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-024-00476-9