Abstract

In recent years, “AI hype” has taken over public media, oscillating between sensationalism and concerns about the societal implications of AI growth. The latest historical wave of AI hype indexes a period of increased research, investment, and speculation on machine learning, centred around generative AI, a novel class of machine learning that can generate original media from textual prompts. In this paper, I dive into the production of AI hype in online media, with the aim of prioritising the normative and political dimension of AI hype. Formulating AI as a promise reframes it as a normative project, centrally involving the formation of public and institutional confidence in the technology. The production and dissemination of images, in this context, plays a pivotal role in reinforcing these normative commitments to the public. My argument is divided into four sections. First, I examine the political relevance of stock images as the dominant imagery used to convey AI concepts to the public. These stock images encode specific readings of AI and circulate through public media, significantly influencing perceptions. Second, I look at the dominant images of AI as matters of political concern. Third, as generative AI increasingly contributes to the production of stock imagery, I compare the epistemic work performed by AI-generated outputs and stock images, as both encode style, content, and taxonomic structures of the world. I employ an entity relationship diagram (ERD) to investigate the political economy of AI imagery in digital media, providing a snapshot of how AI hype is materialised and amplified online. With this study, I reaffirm AI’s normative character at the forefront of its political and ethical discourse.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In both text and image, the public media presence of Artificial intelligence (AI) has grown exponentially. Sensationalist reporting regarding future promises of the technology has entered governmental websites, top journalistic outlets, and inundated leading search engines. In the past year, public media hype surrounding AI has focused on outputs of generative AI, a novel class of machine learning frameworks that can produce text and images from textual prompts. Generative AI products are said to be “[invading] our lives” [1] and ushering in a “wave of information revolution” [2], promising to reform society at all scales: from our relationship with artistic creativity, to global economics [3]. Critical discussion of “AI hype”, or “the misrepresentation and over-inflation of AI capabilities and performance” [4], in public media has grown exponentially. Stakeholders “have concretely started questioning the over-inflated expectations” [5] of the technology, which “[conceal] the reality of AI achievements and [impede] their understanding” [4]. Public discourse surrounding the technology has been criticised for promoting hype [6, 7], fear mongering [8] and perpetuating “AI anxiety” [9], gathered around an “AI risk” of the technology losing control [10], posing a threat to democracy and even humanity.

In tandem with AI hype and linked terminological ambiguity and indiscriminate application of the term “AI” [1, 2], scholarly debate has begun to evaluate the social implications of AI’s “black box” problem [2, 11, 12], in which its operational procedures remain unknowable not only to the general public, but also to AI researchers and stakeholders, with pernicious political and ethical implications. Scholars are calling for greater “interpretability” [11] and “qualitative understanding” [13] of new AI systems. Recent years have seen the growth of explainable AI (IAX), a discipline tasked with “[enabling] stakeholders to understand and retrace the output of Artificial Intelligence models” [1]. The AI Explainability problem asks how “[we can] audit,... trust, and legally defend... something [we do] not understand” [14]. A widespread absence of AI literacy precludes alternative, possibly more democratic modalities of relation and participation, where technological innovation could be “consciously subverted, contested, and negotiated” [15]. The link between AI transparency, accessibility, explainability on the one hand, and democracy on the other, is crucial for problematising AI’s public media hype as a matter of politics.

Throughout its historical oscillations between AI hypes and winters [16], respectively periods of increased and decreased investment and public interest in AI, the announcement of future visions has been central to the bolstering and guiding of public confidence and financial investments in AI research and development [17, 18]. These processes of adoption and sensitisation have been powerfully torqued by oft-clandestine agreements between big tech companies and public media outlets [19]. Since its inception, AI has been a “technological imaginary [with real-world] consequences” [20]. I extend Romele and Severo’s call for theoretical accounts that keep in view both the symbolic and the material dimension of images of AI [21].

Despite the vast body of research prompted by media sensationalism surrounding AI, there is scant exploration linking political and ethical debates surrounding AI’s depiction in popular media with empirical study on the specific mechanisms through which these representations manifest in today's media landscape. I align with Romele and Severo’s call for a “‘material turn’ in the analysis of stock imagery” [21], focusing on the concrete and material drivers of its production and dissemination, and simultaneously join a growing trajectory of research into the normative dimensions of AI, by investigating AI’s public image from a “sociotechnical perspective” [5]. I set out to examine how hyped visions of AI materialise through concrete actors with material commitments. I focus on AI’s “public visuality”, referring to the dominant way through which the media image of AI becomes known and seen by the general public. How is the visual hype around AI created in current online media? What are the political and normative implications of a public media environment defined by these visions? How can we envision representing AI in more publicly beneficial ways?

I explore the topic across four sections. First, I situate the political relevance of stock images, the dominant imagery currently employed to mediate the concept of AI to the public. Second, I take stock images seriously as a matter of politics and aesthetics, which circulate through public media and mobilise specific readings of AI, forming the backbone of the “ambient image environment that defines our visual world” [22]. Third, as generative AI has been increasingly employed in the production of stock imagery [23, 24], I discuss some connections between the outputs of generative AI, and their link with the datasets employed to train them, mostly stock images of AI. This section discusses the epistemic structuring work of both AI-generated and stock imagery, as semantic artefacts which encode and ossify style, content, and taxonomic structures of the world. Finally, I further join theoretical discussion with empirical observation, to capture a timely snapshot of the mechanics by which AI visual hype is becoming materialised and amplified in online media. I explore the political economy behind images of AI with an adapted entity relationship diagram (ERD; [25]), a graphical notation offering an overview of human and non-human entities in the increasingly-algorithmic loop of AI’s public image production [21], and their relationships at a broad system level. My central aim is to interrogate and problematise AI as a foremost normative undertaking with empirical components.

2 Images of AI = (micro)stock images

Looking up “AI” across leading image search engines reveals an algorithmically-ranked mosaic of stock images, exposing their widespread presence across top media outlets, institutional and governmental websites [26] (Fig. 1). Such peculiar images “are always among the first results” [20]. Past research has established the tendency of search engines such as Google to prioritise top-ranking news outlets and stock image platforms, reframing them as windows into the digital image economy of AI [26]. Save for occasional cropping or downscaling, these images of AI reverberate throughout the mediasphere in nearly unchanging iterations.

The persistent hegemonic visuality of AI in public media has been accompanied by a growing body of research. Images of AI have been critiqued for showing AI as dematerialised and distant [20], perpetuating religious iconography [27], sci-fi tropes and clichés [28, 29], anthropomorphism [4, 30], prototypical whiteness [31], racism [32], fear mongering [31], and quelling disagreement or resistance regarding what AI ought to be in the world [20]. Images of AI are case-in-point of the “deep blue sublime” [26], an aesthetic category capturing the deep blue visuality of media (stock) images of emergent tech, and simultaneously epistemic orientation built upon affective foundations of awe and sublimity. As such, these images hinder deliberation and investigation into the technology behind them. The images reinforce the link between the signifier (“AI”) and a heavily used set of signifieds (anthropomorphised robots, sci-fi visuals, futuristic interfaces, blue monochromes). By insisting on showing AI as anthropomorphic, the dominant visuals “distort moral judgments about AI [capabilities]” [4]. While the images continue to persist across leading institutional websites [20, 26], the scientific community has largely distanced itself from endorsing such images [33]. The images stand in sharp opposition to the view of AI as a global operation of “material resources, human labour, and data” [34]. This speaks to a split between the conceptualisation of AI as a normative force on the one hand, and empirical enterprise on the other. I situate this paper at the meeting point between the two, attempting to keep both in view throughout the analysis.

The question of AI’s public visibility has mostly been a question of the production and circulation of stock images. These are images produced with no particular project in mind and licensed for commercial (re-)use, mostly on massive online stock imagery repositories. Aiello notes that “stock images are most often overlooked rather than looked at” [22], both in their every-day context and academically by scholars. Stock images form tacit quilting points of “the ambient image environment that defines our visual world [emphasis added]” [22]. Frosh characterises stock images as “the wallpaper of consumer culture” [35], or “the kind of images we notice only peripherally” [36] on our media consumption journeys. Stock images are defined by their “generalized and stereotyped way of representing reality” [20]. With few exceptions, AI is shown to the public in the form of “microstock images” [20, 21, 26], stock imagery created by mostly-anonymous users and resold for low rates (in comparison with traditional exclusive-license stock imagery) on stock image licensing platforms such as Shutterstock, Getty Images, or Adobe Stock [21]. Such platforms have “acquired dominance over vast terrains of public visual culture while... remaining out of sight” [36], resulting in stock images’ forming the “visual backbone of advertising, branding, publishing, and journalism” [22]. The public image of AI has become increasingly bound up with the workings of the stock image industry.

Fundamentally, images of AI live in concrete settings. Romele and Severo observe that literature on stock images has tended to over-emphasise the images’ symbolic dimension, focusing on contents and meaning, at the cost of attenuating “the material processes of [their] production and distribution” [21]. The authors situate the production of the dominant public images of AI as the latest step in the twenty-year process of the “algorithmization of microstock imagery”, which has consisted of: (1) the replacement of creative work with the fragmented, repetitive, photo-editor software-driven production of images “whose only purpose is to increase the chances of sales” [19] and easy classification by the stock image platform’s sorting algorithm; (2) increasing reliance on “semi-automatic keywording” which increasingly joins a certain type of image of AI with its signifier; and (3) the immediate access to the images of AI through algorithmically-driven search engines. By positioning the production of microstock imagery as a form of “digital labour”, the authors distance the images from being expressions of reflexive or autonomous artistic production, instead focusing on their commodity character and suspension in increasingly automated algorithmic loops of production and circulation of media images online, and addressing how “the success of these images depends on being among the top search results” [21]. Hence, the question of dominant media images of AI increasingly becomes a question of the conditions of their production and circulation.

The authors’ substantiate how “AI ends up creating the images, and thus... imaginaries, of itself” [21], as “AI algorithms [increasingly] determine the way AI is visually represented”. The increased adoption of AI-generated stock images espouses “a future in which human producers will be pushed completely out of the loop”, completing the “algorithmic loop” of the production of AI microstock imagery, in which our contemporary imaginaries about algorithms qua AI are themselves algorithmic productions. I will return to this point in Sect. 4, further elaborating on the epistemic structuring role of generative AI in closing the loop and exploring some practical consequences of the recursivity for generating better images of AI. The currently dominant image of AI seems to persist in the media despite growing critical awareness and tends to live in search engines and online media outlets in the form of microstock images. Given the images’ unique status, inseparable from their consumption and circulation, yet at the same time artistic productions of some sort, I wish to explore the political implications and underpinnings of what this way of seeing might mean.

3 Seeing AI means showing AI in a certain way

3.1 Imagining AI

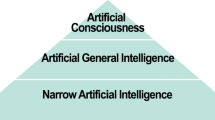

AI is an overloaded signifier [2], simultaneously referring to a loose cluster of closely related academic disciplines and industries, sprawling global enterprise, or normative commitment with empirical components, i.e. “practice-based speculation” [37]. As such, it is affected by the “problem of representability” [20]. The impossibility of compressing it into one single, verisimilar visual representation, merits little defending. An image of AI is invariably a synecdochic stand-in for a whole. Hence, each showing of AI-as-image opens one frame of interpretation, and shutters others, in what is always a creative and curatorial act [1], always already caught in larger-scale workings of ideology and politics.

At first glance, the bigger-than-life images might simply be indexing the level of general public understanding or unfamiliarity with the concept, given their continued ability to trade as acceptable visual stand-ins for “AI” in public media. The deep blue sublime AI imagery may be picking up on a collective fascination and captivation with technological innovation, “technomystical [sic] impulses... masked in the pop detritus of science fiction” [38]. Furthermore, sci-fi images of AI may also be reframed as a robust societal canvas for “problematizing human issues through AI as a metaphor” [29]. These fundamentally speculative visuals might disclose “what AI means in the popular culture today” [39], tracing the contours of common conceptions of what AI ought to be able to do. A sympathetic reading acknowledges the images’ entanglements with pop-cultural tropes and clichés about machinic creativity, whose roots reach far back.Footnote 1 This line of reasoning meets resistance in the fact that these images are mostly produced by low-paid digital workers [21], and chosen by actors within the media outlets that feature them. In the proceeding sections, I explore another angle, the epistemic work of algorithmic circulation and diffusion of visuals through the online space.

The production of future visions has been central to the public sensing and knowing of AI. Originating in science and technology studies (STS), Jasanoff and Kim’s (2009) concept of “socio-technical imaginary” has seen widespread use in studying the expression of political visions through technological innovation. The concept theorises the link between “imagination and action”, i.e. the technological promises made to the general public by technologists and institutional stakeholders involved in technological innovation (originally the state), and their empirical objectives formulated to realise said future visions [40]. The concept is distinguished from “media packages” (Modigliani 1989 qtd. in [40]), discursive frames that attain through “the repeated use of words and images in public communicative space” [40]. The socio-technical imaginary seeks to keep in view the transition between the normative and empirical, by linking the production of content and ideas with policy and action.

As public narratives, socio-technical imaginaries “shape how society sees, interprets and organizes [new] technology” [9]. Such imaginaries are fundamentally the subject of ethics, producing moral claims as they “[encode] collective visions of the good society [and its technologies]” [41]. Over time, socio-technical imaginaries may sediment into mental models, “shared [understandings] or [representations]” [42] of technological innovation. Ontologically, socio-technical imaginaries presuppose a political arena controlled by powerful actors distributing and making common certain visions to the public. The actors which furnish the arena of AI’s public meaning are those with the power to bring a certain visibility to the public eye.

From its inception, the manufacture of future visions of AI has been crucial to securing funding and development support. Law investigates the beginnings of AI’s development in the 1950s to show the entwinement of government investment, scientific research, and cultural production in securing and guiding the nascent discipline’s future [18]. The author explores how “computer scientists resisted... the state... by fabricating imaginaries to covertly exert influence over the research environment” [18] and “attract the interest of necessary allies” [18]. The analysis of the efforts to secure the future of AI’s early development demonstrates how “the state’s monopoly on sociotechnical imaginaries can be understood in less certain or absolute terms” [18]. The author further highlights that the role of artistic and cultural productions within sociotechnical imaginaries is to shape “contemporaneous perceptions... rather than accurately predict” [18] future developments of technology. The role of cultural productions has been central to the securement and production of optimistic sociotechnical imaginaries about AI.

3.2 Politics and (An)aesthetics of images of AI

Admitting the political power of images of AI rests upon a reading of politics based upon the control over images. Rancière’s political thought imports necessary nuance to understanding dominant microstock images of AI as a matter of aesthetics and politics. For Rancière, politics revolves around the struggle for the control of the distribution of the sensible, defined as “a set of relations between the perceptible, the thinkable and the doable that defines a common world”, and which allocates who is permitted to do what within it [43]. For Rancière, democratic politics is not about consensus [45]; rather, it crucially involves dissensus, the practice of continually challenging and disrupting existing common sense, “the frame within which we see something as given” [45], towards emancipatory means, rebalancing the distribution of the sensible in the process. Hence, politics rests on the ability to disagree. Activist acts of dissensus are “relentlessly plug[ged]” [45] by those in power, with the power to speak and determine how things ought to be made sense of. The quelling of disagreement regarding the distribution of the sensible, or pervasive consensus, signals the demise of dissensus and marks the death of politics. The connection between politics and aesthetics, i.e. the collective practice of sense-making, emerges through the possibility of art to open up spaces of dissensus, or disagreement, with the current distribution of the sensible. Autonomous artistic production may destabilise the stronghold of the current distribution of the sensible by “hollowing out [the] ‘real’ and multiplying it in a polemical way”, and “re-configur[ing] the fabric of sensory experience” [45] in the process.

Romele addresses the ethical and political concerns of the currently dominant images of AI. Under a referentialist framework, the images are unethical given their failure to represent AI accurately, clearly, or humbly. Since their lack of referentialism is clearly obvious, this is not a problem. The author highlights how Rancière’s thought “paves the way to a deeper critique of... images of AI” [20]. The author observes that the “dominant imagery of AI implies a specific distribution of the sensible... [maintaining a gap] between experts and non-experts, insiders and outsiders”. The author calls for images that promote dissensus, or “the concrete possibility of thinking and building a new form of (technological) democracy”. Dominant images of AI perpetuate “anaesthetics”, visual forms that pacify political disagreement and desensitise the public about the urgent issues of AI development and delivery, while “promoting forms of consensus about the general hopes and fears about AI” [20]. The author advocates for “pensive” images of AI, built upon the “presence of multiple planes... of interpretation,” directing thought into more than one direction. Loosening the stronghold of AI’s dominant visual language may open up space for more pluralistic public participation.

Dissensus, contestability and debate are central to thinking of “better” images of AI, politically speaking. Honig’s concept of “public things” further situates public images of AI, qua stock images, as material artefacts of public concern that co-shape how we envision ourselves in relation to “shared futures” [46]. Traditionally understood as public infrastructure—parks, bus stations, cinemas—public things represent material axes of political discourse. When serving the community, public things form a strong “holding environment” and serve as the discursive infrastructure to “create a solidity” upon which citizens gather and defend [46]. When divisive or unsuccessful in their role of public representation, “they provide a basis around which to organize [and] contest” received forms of collective engagement [46]. Given the growing criticism and disillusionment, dominant public images of AI could be considered unsuccessful from a citizen perspective.

By defining the “ambient visual environment” [22] of contemporary media, stock images influence “our collective capacities to imagine, build, and tend to a common world collaboratively” [46]. In the context of public journalism on AI, text, and image both play crucial roles in positioning and guiding the distribution of the sensible. The visions presented to the public expose few gripping points for communal deliberation, contestation, or coming together regarding our future with the technology. Due to this, they form a weak holding environment. Reading the collective archive of social imagery as a holding environment allows for normative investigations into its health. For images of AI, the notion of a collective visual holding environment guides discussion regarding the status quo of media imagery of AI towards social and political ideals, i.e. what kinds of collective political action would be needed to envision and bring about more equitable alternatives?

Practically, the problem of the dominant images of AI is that they foreclose the development of literacy and “do not allow for the emergence of a public debate about AI” [21]. “One can watch thousands of similar images of AI without having to develop any critical reasoning about AI” [20]. The images maintain a certain order “between things that are said to be perceptible and the sense that can be made of those things” [44], especially given the fact that for the vast majority of people, perceiving AI is through encountering it in the media. Having established that showing AI accurately and objectively is not an option, the guiding question for what kind of images of AI to create becomes further unclear.

The problem of showing AI to the general public is the task of “showing not only the technology itself, but also its [socio-cultural] implications” [20]. While AI happens through labs, data centres, employs human labour, and harms the environment [47], it crucially includes its imaginative and symbolic dimension; “AI [is] a technical and scientific phenomenon... [as well as] a social and cultural fact” [20]. According to Romele stock images of AI tend to either: (1) represent the algorithm itself; (2) depict the technological contexts of AI application; (3) or most commonly, depict hyped sociotechnical imaginaries of AI [20]. Problematising the issue of visualising AI in less sublime ways, past research has distilled three modalities of aesthetic resistance to dominant AI imagery in public media [38]: (1) using symbolic language otherwise, employing artistic production to diversify the visual forms AI could take in a politically consequential, dissentual manner; (2) demystifying the technology through documentary realism, showing the terrestrial daily working of the technology through named and localised instances; (3) critical projects of cognitive mapping that open up the “black box” of AI and demonstrate its complexity. In the context of politically desirable images of AI, those that lead to deliberation, contestation, and assemble publics around their reception, in the goal of nurturing a healthy visual holding environment within public media, two paths are cut: using symbolic figuration differently, i.e. in politically emancipatory ways that promote a greater plurality of positions within the public arena; or foregoing its use in favour of realistic depictions.

The first path is well-trodden [20, 38]. The currently dominant images of AI are a case-in-point of the pernicious nature of unchecked agreement or consensus. The power of better images of AI could be within their artistic potential to “[undo], and then [re-articulate], connections between signs and images... [that frame] a given [common] sense of reality” [45]. Such images may shift public perception towards dissensus, diversifying the range of imaginaries of AI development. Given the centrality of speculative future visions in AI development [16, 18], diversifying such visions going forward becomes highly politically relevant. The political import of a visuality of AI marked by dissensus, is that of a highly fragmented arena of different thought-provoking metaphoric visions competing [20], which encourages the viewer to actively seek meaning rather than passively overlook the currently dominant imagery.

Having affirmed the role and importance of divergent, pluralistic visuality of AI, I wish to entertain another avenue of viewing the images as unethical and unpolitical, by returning to the point of referentialism. Following Romele, images of AI could be considered unethical because they do not adhere to “referentialism” by accurately and realistically representing empirical aspects of AI innovation [20]. A possible advisory might be “moderate [or no] use of visual representations of AI” [20]. Given the current increase in visual-based media consumption, this seems like a fading prospect. Given the fact that AI operations are environmentally extractive, commonly invest public funds, and contribute to the growth of economic divisions, greater awareness of these processes would be in the public interest. Perhaps an ethical advisory prioritising referentialism could return, as showing the material agents, actors, and locations involved in the development of AI would inevitably increase the critical literacy that is absent from the currently dominant visuals.

For those on the “outside” of AI innovation [20], looking up AI for the first time and being met with abstract visuals and lofty claims about its social potential, likely does not lead to knowledge in the way of AI transparency and accountability. In the context of social media and search engines, “images are most often detached from, and perceived outside from, their [original] context” [20]. Hence, the inherent communicative ability of each image becomes central. I argue that since the currently dominant images do not show “what is really being done” [21] in AI, they are inherently misleading, and thus are unethical. Under this reading, ethical images of AI would try to show the empirical aspects of AI as faithfully to reality as possible. The current sensationalist images of AI are revealed as “smokescreens: making us... look in astonishment one way, while the real technology work is taking place elsewhere” [26]. This accords with the trend of media reporting to show global extractivist infrastructures to the public as anonymised, sublime, and precluding accountability [48]. Hence, better images would make AI legible, accessible, sensible. And at the same time, promote the ability for AI research and development to be contested, confronted, and argued about in the public.

The prescription of accurately visualising the empirical workings of AI sets the standard for public media imagery high and stands sharply against the generic visual blueprint and mechanics of microstock imagery, which are produced to be unspecific and easily recontextualisable. Indeed, the deep-blue sci-fi visuals “respond to a specific need [that other types of images] are unable to address” [20]. An alternative here might be to show verisimilar representations of processes such as dataset-labelling, or of the infrastructure that ultimately fuels it. The question of ethical visual reporting on AI here then concerns the use generic microstock imagery to represent AI at all.

The production of media images and artistic interventions that un-black-box AI “can play a critical role in raising awareness of the impact, showing the environmental abuse and human costs... and encouraging a rebellious activist culture” [48]. Showing AI as named, accountable infrastructure, or mapping it out in a didactic manner, aids learning, and may constellate publics around actual implementations of AI, rather than abstract fears or expectations. Such visual interventions may promote media literacy, which is a central component in seeing past the inflated visuals and claims made about AI to the general public [15, 49]. At the same time, it is important to avoid a fallacy and admit that visualising AI through “objective” means does not necessarily lead to politically emancipatory outcomes. Explainability does not lead to participation, and participation does not automatically lead to equality.

In both persisting or desisting from the use of symbolic language, easing “the monopoly of the forms of description” [44] becomes central to the political project of better AI images. The other component is showing AI accurately, to the extent that such accuracy aids critical public debate on AI development and innovation. Prioritising the “horizon of emancipation” [44] in a remediatory politics of images of AI, means centering the question of which voices should be emancipated and lifted, and which should be attenuated. The directive becomes clear for images that are less prototypically white, less sublime and religious, less anthropomorphic, and less sensationalist or hyped. On the level of labour production, the question concerns the systems that produce and circulate these images. Attention may be turned to smaller producers, and collective political action that questions the current algorithmic systems that keep the tired visuals on top.

4 Stuck in the loop—ossifying social categories

Recent months have seen “an explosion of interest, hype, and concern” [50] surrounding generative AI, epitomising the current AI hype wave. Journalism on generative AI has become largely coextensive with reporting on Elon-Musk-founded, Microsoft-backed machine learning company OpenAI and its Generative AI products, text-generating ChatGPT, and image-generating DALL·E. Launched in January 2021 as “a neural network... that creates images from text captions” [51], DALL·E took the world by storm, reportedly being used to generate over 2 million images per day as of late 2022 [52]. One year later, the company released DALL·E 2, presented to the public as “a new AI system that can create realistic images and art” [51]. In between, an important discursive shift occurred: the “neural network” has become an “AI system”, which can now create art rather than merely images. This episode cuts to the core of this research, showing how AI innovation has transpired in lock-step with accompanying AI hype, propagating a socio-technical imaginary of AI qua anthropomorphised, creative, autonomous entity [4].

Generative AI systems have become increasingly employed to replace the production of stock imagery, an industry already built on increasing automation and rule-based production of images [21, 36]. In the case of Images of AI, the results have further reinforced the ossification of the familiar blue visuals. Engaging with DALL·E 2 in an exploratory manner and prompting the product to generate images of “Artificial Intelligence” (Fig. 2), generates images that nearly precisely mirror the search results obtained on major online search engines (Fig. 1). The images generated by DALL·E 2, and stock images, might both be recalled by “the industrialisation of automatic and cheap production of good, semantic artefacts” [53]. In the case of images of AI, DALL·E outputs are “recursive aesthetics” [38], with outputs repeating differently the inputs used to train the network, and which become the input for future iterations. In this section, I probe what may be revealed by temporarily examining stock images and Generative AI outputs through a joint lens of epistemic machination.

DALL·E 2 is trained on online images combined with their textual descriptions. Its makers acknowledge the potential representational biases that are encoded in the image results, such as encoding western, male, white-centric imagery [54]. Furthermore, by being trained on online images and captions, DALL·E 2 equates what exists with what exists online. Such a predisposition inevitably disenfranchises forms of expression that are not demarcated, or perhaps absent, from the online space. In the process of scraping the web for training data, there is little possibility to opt-out from being excluded from the training dataset. Image-makers are locked-in unless prompting expensive reconsiderations by the makers of the algorithm, such as cleaning up the data, re-training, or building additional functionalities on top of the network that amend the outcomes. This adds to the power differentials built up by the proliferation and domination of large ML networks such as DALL·E 2 in the contemporary Creative AI landscape, and illuminates the political economy of contemporary AI visuality, in which a few powerful actors determine and structure the ways by which the technology materialises, i.e. comes to matter publicly. A similar process of selection and decision may be seen in leading stock photo marketplace platforms, where human and algorithmic moderation processes determine the final inclusion and presentation of images for licensing and reuse.

Stock images and Generative AI training datasets both rely on the ossification of style and the production of iconicity—they are concerned with a “generic image” from which variations can stem. A central function of stock image distribution, and dataset labelling, is compressing a social category out there into “a unique referent... reducing [photography and image-making] to a machine for producing stereotypes” [36]. In the process, the world is carved up into discrete categories, through the assignment of which identities ought to belong into which categories, and how these categories ought to look like in the world. Both stock image platforms, and generative AI systems, labour under the taxonomic assumption that concepts have a “visual essence” which “unites each instance of them, and that that underlying essence expresses itself visually” [55]. In concepts such as “four-leaf clover”, the social ramifications of such epistemic structuring might be banal. In the case of representing social identities, or sensitising public perception of nascent or contested concepts, the ramifications grow in political consequence and may lead to pernicious essentialization.

By granting public access machinic creativity, generative AI could be said to open up, democratise, and diversify access to creative expression and imagining-together for the public. The same could be said for stock image platforms, which similarly unlock commodified visual expression for personal and industry application. In that sense, both generative AI and microstock broker sites might represent commodified artistic expression. The main difference appears to be the more instantaneous generation of infinite variations, which are always unique and instantaneous. The nature of the production of microstock imagery reveals a process tending towards a similar machinic quality [21]. However, while at first appearing democratic and amenable to public representation, makers of generative AI, much like stock image platforms, greatly monopolise the image economy. First, by imposing and endorsing a hegemonic and minority way of seeing, namely that of its creators and consumers, onto the world. And second, by establishing an “aggressively monopolistic” global market dominance [36, 56]. Granted increasing future adoption [23, 24], the proliferation and intensification of an image economy produced by generative AI, trained on increasingly-AI-generated stock images, presupposes a recursive loop, as the inputs are fed towards the outputs. This phenomenon has been recently linked with upcoming generative AI “model collapse” [57], fed by a recursive feedback loop of outputs and inputs of generative AI [58], resulting in complete dissolution of original categories, and in meaningless outputs.

Looking into images of AI, both stock and generated, corresponds with examining “the underlying politics and values of a system, and [analysing] which normative patterns of life are assumed, supported, and reproduced” [55]. Human agents, along with their biases, “are inevitably involved in creative processes that integrate AI” [37]. This raises broader reflection of the implications of generative AI qua active epistemic agent, participating in the creative process by offering pre-formed suggestions that prime human creativity. Romele and Severo [21] situate the growing role of Generative AI in the creation of stock imagery in “the algorithmization of our societ[y]” into a “recursive society”. This might “complete” the algorithmic loop, the human producer might become absent from the loop of the automated production of microstock imagery for AI, by which “the algorithmic loop is complete, since AI algorithms determine the way AI is visually represented and hence impact people’s expectations and imaginaries” [21]. Combined with the aforementioned existing self-reinforcing algorithmic logics which drive the production of micro-stock imagery towards sameness, “the emergence and success of generative AI heralds a future in which humans can be completely put out of the loop” [21]. This summons the figure of the Ouroboros, AI “eating its own tail”, through the tightening loop of aesthetic recursivity. The growing automatisation represents an affront to politically consequential image-making. The visual referent of what ought to be understood as “AI” in public media is becoming increasingly locked-in, atrophying the horizon of possibility of aesthetic resistance. This process crucially depends on an interworking of the material infrastructure through which the image of AI is made public.

5 Political economy of images of AI

The development, deployment, and regulation of AI crucially hinge on its public perception [9], which is increasingly driven by the production and consumption of digital media, not least through looking up “AI” online. The problem of AI hype in contemporary media is ultimately a problem of the circulation and amplification of a certain socio-technical imaginary through a digital ecosystem of human and nonhuman actors. An actor-based approach aids in viewing the impact of non-human actors such as sorting and ranking algorithms. In this section, I articulate how images of AI become visible to the public within the ecosystem of online media using an abridged version of an entity relationship diagram, adopting a “[world] view... [consisting] of entities and relationships” [25], in which arrows represent the directionality of the relationships between given entities (Fig. 3).

Exploring the production of images of AI within online media inevitably leads to online media outlets, where these images accompany textual reporting. Actors within the media outlets that produce and disseminate visual material in the context of journalistic reporting choose which image will accompany a given article, institutional website, or policy document. The actor, such as the art director, in journalist in the case of smaller outlets, may choose to work with an image-maker, choose an image from a stock photo provider, or increasingly, use generative AI to create the required image to accompany the often-sensationalist article reporting on AI. In that sense, the hegemonic image of AI becomes further intertwined with the content used to disseminate its research, innovation, and policy to the general public. This further naturalises a given distribution of the sensible (cf. Rancière). Numerous media outlets hold exclusive-use contracts with the dominant stock photo providers, which give them preferential access to the licensing and reuse of their imagery, which may itself be human-made and increasingly AI-generated.

Image-makers straddle the line between producing socially intelligible and sellable “similar images” [20], or opting for novel metaphoric figurations. Taking a bird's eye view provincialises readings that single out the authorial and emancipatory potential of design per se, instead reframing public design as an a force whose political and expressive power is intrinsically “hamstrung”, bound by a range of political agendas of other actors that greatly attenuate its political effects [38, 59]. The image-makers are mostly people looking to earn a side-income, representing a class of precarious freelance graphic designers, rather than enlightened autonomous artists. “Creative moments” soon become un-fun acts of “digital labour” [21]. Stock images are particularly notable, as they are made by one person to be bought by another. Hence, claiming that such images might reflect their maker’s “desire to see potential technologies become realities” [18], is quickly complicated by the fact that the images are made, sold, resold, and enter the public eye through a distributed and increasingly algorithmic feedback loop [21].

The possibility of effective aesthetic resistance, producing different visuals and distributing them throughout digital media into the public eye, is met with resistance; on dominant stock image platforms, which have greatly monopolised media imagery distribution [36], corporate agreements prioritise producing for scale and discourage smaller-scale, divergent figurations from becoming adopted and distributed. In addition, epistemic mechanics of automated keywording and algorithmic sorting outlined in the previous sections [21], tend to accept only certain images as belonging to “AI”, while rejecting others. The overview diagram imports another way of viewing “the subjugation of the producers of microstock images... to technological and algorithmic logics” [21]. Image-makers are merely one in a much larger constellation of actors, whose complex interplay results in the currently prescribed visuality of AI becoming and staying public.

The search engine complicates traditional models of commercial media influence, in which corporations directly influence visual media in the form of advertisements. Looking up something on Google, stock images appear prominently as microstock platforms are linked directly in the search results. This may point to commercial agreements between the search engine and stock image providers [60]. This creates an unexpected confrontation between uncontextualized stock images, and the viewer. In most cases, however, the image search results display top-ranking news outlets, which feature much of the same stock image material. Google’s tendency to keep the same search results on top over time [26, 61], further adds to the ossification of the existing visual style.

Within the media, the choice of images is left up to editorial agents within the news corporation; in search engines, the choice is algorithmically mediated, and points to the media outlet or search engine’s own commercial imperatives. Past research has shown that Google tends to prioritise top news and institutional websites, and keep the most popular images in top position over time [26]. In addition, the search algorithm is fundamentally aligned with the platforms’ own politics and hierarchies of relevance [61], which further illustrates the complex power relations involved in the production of public visions of technological innovation within online media. Furthermore, by linking “AI” with search results that define and explain the technology, search engines such as Google further link hegemonic representation with the action of seeking knowledge, or “looking up” AI. In that sense, search engine algorithms of both stock image sites and the web more broadly, contribute towards “how people seek information, how they perceive and think about the contours of knowledge, and how they understand themselves in and through public discourse” [62].

Suspended against the increasing solidification and AI-powered siloing of what “AI” means in terms of images, action at the level of changing the algorithm might become necessary. Stock image platforms and search engines have made efforts “to promote different visual representations of social reality” [20] in the past. Algorithmic adjustments have been made by Google following disclosure of other problematic keywords [63], granting the precedent remains for an algorithmic-level change of a keyword’s online image economy. This might depend on the critical load of scholarship. Simultaneously, the currently dominant image perhaps serves big tech’s aims of dominance in AI research and development.

Microstock images of AI illustrate the concentration of “technoscientific futures... [into] artefacts” [18], and their link with a broader arena of contestation happening far beyond the surface of each individual image. The case of microstock imagery of AI shows that “the contest to represent progress... can be read in less totalising, unidirectional, and martial terms” [18] than those typically associated with the sociotechnical imaginary, and speaks to the growing power of algorithms, and the transmission of imaginaries within everyday media interfaces. Much like the enterprise of AI itself, the production and circulation of its images must be understood as a “distributed phenomenon” [64]: “the responsibility lies and lives between all agents of the image lifecycle” [26]. The diagram provincializes individual agents as parts of a much broader process by which the public visuality of AI comes to be manufactured. Hence, agitating one node might lead to a change in the others, rebalancing the distribution of the sensible in the process. Easing sensationalism in image might have effects on sensationalism in text, and so forth, offering the potential to destabilise the dominant imaginary. This requires conscious political action and agitation.

The question of AI’s visibility is ultimately a question of power differentials, of the struggle to control the perimeters of public discourse. AI could also be defined as an overlapping imbrication of diverse “frames of thinking... [across communities of] developers, researchers, business leaders, policymakers, and citizens” [5], suspended between mental models, and socio-technical imaginaries. The power, however, is not enacted directly by a ruling elite. It lives through repeated enacting of tried-and-tested clichés, and increasingly, the algorithms deepening the grooves of their circulation.

Nonetheless, it is important to remember that every act of visualising AI is, theoretically, an artistic gesture, which reveals certain things and hides others by the same token. The pathway to contest the dominant imagery is becoming ever more difficult to find. Change would require media outlets to consciously retrieve images from different sources or employ in-house image production in different ways, and the search engines to implement algorithmic adjustments and reweighting to allow less-seen visuals to bubble to the surface. This is linked with the importance of activist action, for instance hashtag hijacking [65], and other forms of subversive conduct that erode the hard-set algorithmic grooves through which the current images are produced. At the level of artistic production, the space for desistance against the tired dominant visuals remains in publicly-funded creative production [38], and perhaps a commons-based approaches to dataset creation [66]. Initiatives such as Better Images of AI [67], testify to the productive potential of independent attempts to establish alternative stock image collections which disturb the current digital media image economy used to represent AI.

6 Conclusion—AI as promise

I have set out to describe how dated technoscientific futures enter and get “stuck” at the surface of online media, and hence in the collective imagination. The status quo speaks to a political economy of the current visuality of AI, which is supported by both symbolic and material processes. In this study, I have climbed steps, from the individual image to its embedding in digital media, in order to show the interconnectedness of different political concerns in how the image of AI has been show to the general public in contemporary online media. In the case of AI, media have played a pivotal role in fanning the flame of the hype and thus feeding the production of a certain sociotechnical imaginary about AI. Its remaining in place, however, also has a lot to do with algorithmic logics that keep the same tired imagery sticky at the top, and reward cultural productions that bring more of the same [20, 21].

Images of AI are fundamentally a matter of politics, and our “[public] understanding of [AI] is morally [and politically] relevant” [13]. In their partial capacity to torque public perceptions, images obstruct a more comprehensive and equitable social understanding of AI. For that, images must be studied as part of the broader operation they exist within. While produced by a handful of private actors, images of AI are public things. Within the status quo, they afford a weak holding environment, and allow for little deliberation or contestation. As the public image of AI is becoming increasingly managed and produced by generative AI models, the political critique of public-facing stock images of AI may simultaneously also be armed as a critique of the present dataset politics employed in training generative AI. Taking a distant view and tracing the connections between the diverse actors and stakeholders involved in the production of AI’s public image aids to defend against a range of deterministic positions and explore the complex interplay of interests driving the image of AI in contemporary digital media.

Throughout the paper, I have sought to affirm a reading of AI as normative first, empirical second, and of its public image as always embedded in a socio-political context, shaped by future visions surrounding AI’s promise of technological innovation. The current AI visuality is part of a historical pattern of hype, spearheaded by glowing promises of an AI-driven technocratic future, made possible by increased investment in AI research and development. Looking at AI as a promise reveals that the ways in which it has been explained fundamentally depend on context and audience [43]. AI becomes revealed as a series of promises of transformation, to different audiences, in a given historical moment. Imagination, future promises and speculations crucially hold true for all stakeholders in the process, bearing substantial differentials in the power to enact and affect changes in public perception and sensibilisation, of aesthetics (sensu Rancière).

With this paper, I invite further deliberation of whether “hype” falls under what AI fundamentally is, rather than an irregularity from an otherwise stable empirical enterprise. A provisional distinction here might be to label “AI” as essentially corresponding to its own socio-technical imaginary, a set of normative commitments with empirical components related to machine learning (ML), as a constellation of operations involving data, labour, and earthly resources [18, 20, 34]. Under this reading, the function of the exalted imagery may be viewed as keeping open and diffuse the number of roles and potentials that AI could inhabit, fuelling socio-technical imaginaries, while populating the future promises with mostly commercial ventures.

The question of context is central, of what it means to try and make “AI” understandable, legible, relatable, and for whom. In the context of the inflated techno-optimistic promises of the current AI hype period, and possibilities of sensitising the general public towards public participation, contestation, and deliberation with AI research and innovation, attenuating the dominance of the exalted imagery might be productive. In that capacity, the current visions spread disinformation, hype, and inflate the technology’s true potential [26, 67]. The urgency remains for producing visuals that aid AI literacy [15], yet also disclose its normative power in a way that complicates social relations in the process [20, 38], and fundamentally aids the discursive potential of imagery, rather than bolstering anodyne “anaesthetics”, which “impede or anaesthetise... disagreement” [20].

The conceptual model of this paper could be further corroborated by applying it to specific instances of journalistic reporting, to explore the precise relations between the named actors, and gain further insights into the conditions of production of contemporary media images of AI and other emergent technologies. Further ethnographic research with agents involved in the image-production cycle [21], can bolster the analytical relevance and applicability of such entity-relationship mappings, and add an empirical backbone to mental models approaches by revealing frames of thought and imaginaries guiding actors within the image production cycle. Additionally, research might take up analysis into official documentation and promotional material employed by technologists or focus on the textual tropes employed to report on AI within public media. Lastly, conducting a genealogy of the deep-blue visual language of AI can help to provincialise the present moment of visual AI hype.

Denting the present sociotechnical imaginary remains fraught with difficulty, as the dominant visual language grows increasingly locked-in. The horizon of possibility of dissensus, of doing otherwise, is closing due to the algorithmisation of visual production. The solution might be in collective-level political action. Ultimately, however, systemic-level action is needed to substantially subvert the problem. AI ethics must fundamentally not glance over the distribution, dissemination, and regulation of normative statements: sociotechnical imaginaries, promises and imagery that pave the future path forward towards a certain distribution of the sensible, a certain way in which AI is made relatable and accessible as it becomes further integrated into our lives. Swapping the tired visuals for another set of symbolic forms does little if the fundamental ideological and material processes through which AI visuality materialises are not meaningfully addressed. Ultimately, changing the images requires a change of the material conditions that result in their persistence at the surface of visibility.

Data availability

The data sources for this research are publicly available Google Images search results, and the image outputs of DALL·E 2.

Notes

For a comprehensive overview, refer to: Cave, S., Dihal, K.S.M., Dillon, S., editors.: AI narratives: a history of imaginative thinking about intelligent machines. First edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press; (2020).

References

Schramm, S., Wehner, C., Schmid, U.: Comprehensible artificial intelligence on knowledge graphs: A survey. J. Web Seman. 79, 100806 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.websem.2023.100806

Devedzic, V.: Identity of AI. Discov. Artif. Intell. 2, 23 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44163-022-00038-0

Chui, M., Hazan, E., Roberts, R., Singla, A., Smaje, K.: The Economic Potential of Generative AI[Internet]. McKinsey & Company (2023). https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/the-economicpotential-of-generative-ai-the-next-productivity-frontie

Placani, A.: Anthropomorphism in AI: hype and fallacy. AI Ethics. (2024 [cited 2024 Feb 23]). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-024-00419-4

Sartori, L., Theodorou, A.: A sociotechnical perspective for the future of AI: narratives, inequalities, and human control. Ethics Inf. Technol. 24, 4 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-022-09624-3

Brennen, J.S., Howard, P.N., Nielsen, R.K.: An industry-led debate: how UK media cover artificial intelligence [Internet]. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, Oxford. (2018). https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/ourresearch/industry-led-debate-how-uk-media-cover-artificial-intelligence

Naughton, J.: Don’t believe the hype: the media are unwittingly selling us an AI fantasy | John Naughton. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/jan/13/dont-believe-the-hype-media-are-selling-us-an-ai-fantasy (2019 Jan 13 [cited 2020 Feb 12]).

Dihal, K.: Can artificial superintelligence match its hype? Phys. Today 73, 49–50 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1063/PT.3.4410

Sartori, L., Bocca, G.: Minding the gap(s): public perceptions of AI and socio-technical imaginaries. AI Soc. 38, 443–458 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01422-1

Milmo, D.: AI risk must be treated as seriously as climate crisis, says Google DeepMind chief. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2023/oct/24/ai-risk-climate-crisis-google-deepmind-chief-demis-hassabis-regulation (2023 Oct 24 [cited 2023 Oct 25]).

Beisbart, C., Räz, T.: Philosophy of science at sea: clarifying the interpretability of machine learning. Philos Compass (2022). https://doi.org/10.1111/phc3.12830

Jiang, Y., Li, X., Luo, H., Yin, S., Kaynak, O.: Quo vadis artificial intelligence? Discov. Artif. Intell. 2, 4 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44163-022-00022-8

Khalili, M.: Against the opacity, and for a qualitative understanding, of artificially intelligent technologies. AI Ethics. (2023 [cited 2023 Oct 25]). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-023-00332-2

Benois-Pineau, J., Petkovic, D.: Chapter 1—Introduction. In: Benois-Pineau, J., Bourqui, R., Petkovic, D., Quénot, G. (eds.) Explainable Deep Learning AI, pp. 1–6. Academic Press, Cambrdge (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-32-396098-4.00007-7

Woo, L.J., Henriksen, D., Mishra, P.: Literacy as a technology: a conversation with Kyle Jensen about AI, writing and more. TechTrends 67, 767–773 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-023-00888-0

Cardon, D., Cointet, J.-P., Mazières, A.: Neurons spike back. The invention of inductive machines and the artificial intelligence controversy. Réseaux n° 211, 173–220 (2018). https://doi.org/10.3917/res.211.0173

Borup, M., Brown, N., Konrad, K., Van Lente, H.: The sociology of expectations in science and technology. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 18, 285–298 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1080/09537320600777002

Law, H.: Computer vision: AI imaginaries and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. AI Ethics. (2023 [cited 2024 Feb 25]). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-023-00389-z

Papaevangelou, C.: Funding intermediaries: Google and Facebook’s strategy to capture journalism. Digit. Journal. 12, 234–255 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2022.2155206

Romele, A.: Images of artificial intelligence: a blind spot in AI ethics. Philos. Technol. 35, 4 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-022-00498-3

Romele, A., Severo, M.: Microstock images of artificial intelligence: how AI creates its own conditions of possibility. Converg. Int. J. Res. New Media Technol. 29, 1226–1242 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565231199982

Aiello, G.: Taking stock. Ethnography matters. https://web.archive.org/web/20230320165806/https://ethnographymatters.net/blog/2016/04/28/taking-stock/ (2016). Accessed 28 Apr 2016

Edwards, B.: Adobe stock begins selling AI-generated artwork. Ars Technica. https://web.archive.org/web/20230729133332/https://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2022/12/adobe-stock-begins-selling-ai-generated-artwork/ (2022 Dec 6 [cited 2022 Dec 24])

Attié, I.: AI generated images: the next big thing in stock media. https://www.stockphotosecrets.com/stock-agency-insights/ai-generated-images.html (2022). Accessed 13 Apr 2022

Chen, P.P.-S.: The entity-relationship model—toward a unified view of data. ACM Trans. Database Syst. 1, 9–36 (1976). https://doi.org/10.1145/320434.320440

Vrabič Dežman, D.: Defining the deep blue sublime. SETUP. https://web.archive.org/web/20230520222936/https://deepbluesublime.tech/ (2023)

Singler, B.: The AI creation meme: a case study of the new visibility of religion in artificial intelligence discourse. Religions 11, 253 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11050253

Steenson, M.W.: A.I. needs new clichés. Medium. https://web.archive.org/web/20230602121744/https://medium.com/s/story/ai-needs-new-clich%C3%A9s-ed0d6adb8cbb (2018). Accessed 13 Jun 2018

Hermann, I.: Beware of fictional AI narratives. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 654–654 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-020-00256-0

Wallenborn, J.: How metaphors influence our visions of AI—digital society blog. HIIG. https://www.hiig.de/en/ai-metaphors/ (2022). Accessed 17 May 2022

Cave, S., Dihal, K.: The whiteness of AI. Philos. Technol. 33, 685–703 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-020-00415-6

Mhlambi, S.: God in the image of white men: creation myths, power asymmetries and AI. Sabelo Mhlambi. https://web.archive.org/web/20211026024022/https://sabelo.mhlambi.com/2019/03/29/God-in-the-image-of-white-men (2019). Accessed 29 Mar 2019

Vidal, D.: Anthropomorphism or sub-anthropomorphism? An anthropological approach to gods and robots. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 13, 917–933 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9655.2007.00464.x

Crawford, K., Joler, V.: Anatomy of an AI system: the Amazon echo as an anatomical map of human labor, data and planetary resources. https://anatomyof.ai/ (2018)

Frosh, P.: The Image Factory: Consumer Culture, Photography and the Visual Content Industry, 1. Berg, Oxford (2003)

Frosh, P.: Is Commercial Photography a Public Evil? Beyond the Critique of Stock Photography. Photography and Its Publics, Routledge (2020)

Zeilinger, M.: Generative adversarial copy machines. 20, 1–23 (2021)

Vrabič Dežman, D.: Interrogating the deep blue sublime: images of artificial intelligence in public media. In: Cetinic, E., Del Negueruela Castillo, D. (eds.) From Hype to Reality: Artificial Intelligence in the Study of Art and Culture. Rome/Munich, HumanitiesConnect (2024). https://doi.org/10.48431/hsah.0307

Davis, E.: Techgnosis: Myth, Magic, Mysticism in the Age of Information, 1st edn. Harmony Books, New York (1998)

Daniele, A., Song, Y.-Z.: AI + Art = human. In: Proceedings of the 2019 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society. Honolulu, HI, USA: ACM; 2019. pp. 155–61. https://doi.org/10.1145/3306618.3314233

Jasanoff, S., Kim, S.-H.: Containing the atom: sociotechnical imaginaries and nuclear power in the United States and South Korea. Minerva 47, 119–146 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-009-9124-4

Jasanoff, S., Kim, S.-H., editors.: Dreamscapes of Modernity: Sociotechnical Imaginaries and the Fabrication of Power. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/D/bo20836025.html. Accessed 26 Jun 2022

Merry, M., Riddle, P., Warren, J.: A mental models approach for defining explainable artificial intelligence. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 21, 344 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-021-01703-7

Rancière, J.: In what times do we live? In: Kuzma, M., Lafuente, P., Osborne, P. (eds.) The State of Things, pp. 8–38. Office for Contemporary Art (OCA) Norway, London (2013)

Rancière, J., Corcoran, S.: Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics. Continuum, London, New York (2010)

Honig, B.: Public Things: Democracy in Disrepair. Fordham University Press, New York (2017). https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1xhr6n9

Crawford, K.: The atlas of AI power, politics, and the planetary costs of artificial intelligence. https://www.degruyter.com/isbn/9780300252392 (2021)

Demos, T.: Against the Anthropocene: Visual Culture and Environment Today. Sternberg Press, Berlin (2017)

Kvåle, G.: Critical literacy and digital stock images. Nordic J. Digit. Liter. 18, 173–185 (2023). https://doi.org/10.18261/njdl.18.3.4

Fischer, J.E.: Generative AI considered harmful. In: Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Conversational User Interfaces [Internet]. Eindhoven Netherlands: ACM; 2023. pp. 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1145/3571884.3603756

OpenAI.: DALL·E 2. OpenAI. https://openai.com/dall-e-2/ (2023)

DALL·E now available without waitlist. https://openai.com/blog/dall-e-now-available-without-waitlist (2022). Accessed 28 Sept 2022

Floridi, L., Chiriatti, M.: GPT-3: its nature, scope, limits, and consequences. Minds Mach. 30, 681–694 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-020-09548-1

OpenAI.: DALL·E 2 preview—risks and limitations. https://github.com/openai/dalle-2-preview/blob/main/system-card.md (2022). Accessed 23 Dec 2022.

Crawford, K., Paglen, T.: Excavating AI: the politics of images in machine learning training sets. AI Soc. 36, 1105–1116 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-021-01162-8

Soni, A., Hu, K., Hu, K.: Alphabet shares sink as Microsoft extends cloud lead with focus on OpenAI. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/technology/microsoft-surpasses-alphabet-cloud-race-with-openai-bet-enterprise-focus-2023-10-25/ (2023 Oct 25 [cited 2023 Oct 31])

Shumailov, I., Shumaylov, Z., Zhao, Y., Gal, Y., Papernot, N., Anderson, R.: The curse of recursion: training on generated data makes models forget. arXiv (2023). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2305.17493

Martínez, G., Watson, L., Reviriego, P., Hernández, J.A., Juarez, M., Sarkar, R.: Towards understanding the interplay of generative artificial intelligence and the internet. arXiv (2023). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2306.06130

Lavin, M.: Clean New World: Culture, Politics, and Graphic Design. The MIT Press, Cambridge (2001)

Ong, T.: Google will make copyright disclaimers more prominent in image search [Internet]. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2018/2/9/16994508/google-copyright-disclaimers-getty-images-search (2018). Accessed 9 Feb 2018

Rogers, R.: Aestheticizing Google critique: a 20-year retrospective. Big Data Soc. 5, 1 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951718768626

Gillespie, T.: The relevance of algorithms. In: Gillespie, T., Boczkowski, P.J., Foot, K.A. (eds.) Media Technologies, pp. 167–194. The MIT Press, Cambridge (2014). https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262525374.003.0009

Noble, S.U.: Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York University Press, New York (2018)

Cave, S., Dihal, K., Dillon, S.: Introduction: Imagining AI. AI Narratives, pp. 1–22. Oxford University Press, Oxford p (2020). https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198846666.003.0001

Berg, N.G., Tusinski, K.: Social Media, Hashtag Hijacking, and the Evolution of an Activist Group Strategy. Social Media and Crisis Communication. Routledge, London (2017)

McQuillan, D.: People’s councils for ethical machine learning. Soc. Media Soc. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118768

Better images of AI [Internet]. BBC R&D. https://www.bbc.co.uk/rd/blog/2021-12-artificial-intelligence-machine-stock-image-library (2023)

Acknowledgements

The author would like to express their gratitude to Jordi Viader Guerrero (TU Delft) for an insightful discussion regarding the distinction between AI and ML, and the question of the ontological essence of stock imagery in connection with the generative AI outputs.

Funding

No funds, grants, or other support was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose. On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vrabič Dežman, D. Promising the future, encoding the past: AI hype and public media imagery. AI Ethics (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-024-00474-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-024-00474-x