Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) has been applied in healthcare to address various aspects of the COVID-19 crisis including early detection, diagnosis and treatment, and population monitoring. Despite the urgency to develop AI solutions for COVID-19 problems, considering the ethical implications of those solutions remains critical. Implementing ethics frameworks in AI-based healthcare applications is a wicked issue that calls for an inclusive, and transparent participatory process. In this qualitative study, we set up a participatory process to explore assumptions and expectations about ethical issues associated with development of a COVID-19 monitoring AI-based app from a diverse group of stakeholders including patients, physicians, and technology developers. We also sought to understand the influence the consultative process had on the participants’ understanding of the issues. Eighteen participants were presented with a fictitious AI-based app whose features included individual self-monitoring of potential infection, physicians’ remote monitoring of symptoms for patients diagnosed with COVID-19 and tracking of infection clusters by health agencies. We found that implementing an ethics framework is systemic by nature, and that ethics principles and stakeholders need to be considered in relation to one another. We also found that the AI app introduced a novel channel for knowledge between the stakeholders. Mapping the flow of knowledge has the potential to illuminate ethical issues in a holistic way.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is playing an increasing role in healthcare. This has been evident in its applications across various aspects of the public health crises posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, where AI has been implemented to improve detection and diagnosis, treatment procedures and analysis, patient triage in hospital Emergency Departments, drug development, and population monitoring and outbreak predictions [1, 2]. AI is considered essential to the management of future pandemics [1, 2]. While it is beyond the scope of this paper to critically appraised whether AI is suited for healthcare applications, AI in healthcare trend is forecasted to continue [3].

The critical and urgent nature of the COVID-19 pandemic situation created opportunities for the rapid development of AI Healthcare Applications (AIHA). The speed of development of these applications, however, should not come at the price of overlooking ethical considerations [4]. Not considering the long-term consequences and possible biases of AI could reinforce inequalities already entrenched in healthcare systems [5]. Hence implementing an ethics-informed approach to developing future AIHA is of primary importance.

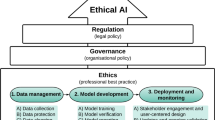

Across different sectors, including healthcare, multiple AI ethics frameworks have been published in the last 6 years. These respond to growing concerns about societal impact, social justice, misuse, or accountability posed by the adoption of AI [6]. Implementing ethics frameworks in AIHA is a complex endeavour and not widely reported in the literature [7]. There is no ‘one size fits all’ approach [7] and contextualisation is fundamental when implementing an ethics framework in healthcare applications. Hence, involving stakeholders in a consultative approach is needed to develop processes for implementation of an ethics framework. Various consultative approaches to implementing ethics in AI for AIHA have been reported in pre-COVID times [8,9,10,11]. However, transparency regarding the decision-making process in the case of conflicts between ethics principles is unclear in these consultative processes [7]. Therefore, there is a need for proactive and inclusive approaches to ethics framework implementation in AIHA to find a balance between the interests of consumers and AIHA providers, and a need to bring clarity and transparency to the process of implementing ethics principles. This exploratory qualitative study aims to investigate the process of implementing ethics engaging with stakeholders using the example of a COVID-19 AIHA.

To do so, we set up a consultative process for a fictitious COVID-19 monitoring AI-based app in an Australian healthcare context. The consultative process strived to be inclusive, egalitarian, and transparent. The consultative process is the first step in the process of implementing ethics into the AIHA, and learning from the outcomes is as important as learning about the process itself. The qualitative study sought to: (1) explore the assumptions, expectations, and perspectives of a range of stakeholders on the ethical issues associated with the introduction and use of an AIHA and the gaps and tensions between the expressed views, and (2) understand the influence of the consultative process on the participants’ understanding and views about the AIHA.

2 Methods

We set up a consultative process involving focus groups and interviews to explore views on ethics, values, and assumptions about the use of a COVID-19 AIHA from a group of people representative of diverse stakeholders. We also incorporated exploration of the process from a meta-perspective, to reflect on the experience of the process by the participants and what they learned from it. This project was approved by the University Faculty of Medicine, Health, and Human Sciences Low-risk Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) (project reference no. 52021978426391). The research team was composed of three women with backgrounds in psychology, engineering, software development and business. Two of the researchers were human factors, healthcare quality and safety experts and one was a PhD candidate who also studied Applied Buddhism. All three were systems thinkers.

2.1 Study design

The design of the process and study was anchored in soft systems methodology (SSM) [12] and critical systems heuristics (CSH) [13]. SSM is an approach to tackle complex issues involving building systems models of the problematic situation to support discussions [12]. CSH is framework composed of questions dedicated to critiquing boundaries of a system through exploring sources of motivation, power, knowledge, and legitimacy [13]. The AIHA was presented to the participants in the form of a simple model to illustrate the scenario presented to them. The expectation was that the model could be further enriched or altered through inputs from participants. The process itself was expected to influence the views of both the participants and the process facilitator. The data analysis followed the principles of a reflexive methodology [14]. The methodology consists of combining different lenses for analysing the data and includes reflections of the researchers about the process. Looking at data from different perspectives and considering the researcher as part of the study aligns with the systemic design approach. While SSM or CSH do not provide specific guidance on the minimum number of participants, peer-reviewed literature on qualitative research sample size suggests that between 12 and 30 participants is sufficient to reach saturation in terms both of identified issues and gained insights [15,16,17]. Saturation is defined in terms of the last interview in which a novel code is identified, such that additional interviews would fail to produce substantial new insight [15].

2.1.1 Development of the app

This study used a scenario based on a fictitious AIHA that helps individuals self-monitor their health and symptoms when sick with COVID-19 (see Fig. 1). The data collected by the app are a mixture of vital signs and answers to short in-app surveys. For practical and legal reasons, a fictitious app was preferred to a real app. While fictitious, it has been imagined by aggregating the functionalities offered by real apps. One functionality was inspired by the app developed by the Stanford Healthcare Innovation Lab in the U.S. to detect early signs of COVID-19 illness [18]. A second functionality emulates self-monitoring apps that include questionnaires to treat COVID-19 patients suffering with mild or moderate symptoms staying at home for their recovery and used by primary care physicians (General Practitioners (GPs)) in Australia [19]. A third functionality was drawn from the U.K. ZOE app that collects data about symptoms and recovery [20].

The app communicates the data to the user’s GP. The data are also used for public health purposes to track infection clusters. To advance the understanding of the disease, all data collected from users and GPs are fed to a Machine Learning (ML) system. The insights generated by the system can help GPs make better decisions when it comes to diagnosis and treatment and follow their patients more closely without the need for physical or in-person contact. It can also help individuals obtain personalised treatment and provides advice on how to best manage their health, early signs of illness or established illness, recovery, and risk factors.

2.1.2 Participant selection

Participants were recruited using the social and professional networks of the study researchers. Invitations were sent by email or LinkedIn. Participants were informed that the primary researcher was a PhD candidate, and the study was being conducted to meet the requirements of the PhD. Participants were also informed that this researcher was originally trained in computer science and spent 25 years working in the high-tech industry. Inclusion criteria were that participants were 18 years or older, spoke English and fell into one of the following stakeholder categories: (1) patients and their support system including caregivers and family, (2) GPs and their support system including clinical and professional staff, (3) AI technology system which includes designers, developers, implementers, marketers and resellers (see Fig. 2). In addition, we strived to include participants with some experience with health insurance, policy and regulations, or ethics committees. As the fictitious app was designed for use in the Australian healthcare context, participants were required to live in Australia. The exception was for the AI technology group since design and implementation of AIHA technology is not limited by knowledge of local healthcare systems.

2.1.3 Data collection

The study comprised three phases: (1) 60-min individual semi-structured and in-depth interviews, (2) 90-min focus groups, (3) 30-min semi-structured individual interviews (see Fig. 3). In phase one interviews, to establish a baseline, the participants were first asked open-ended questions about what health is to the participants, how they would describe the relationship they have with their medical doctor, and their expectations, hopes or fears about AI. Then they were presented with a scenario of the fictitious app and asked to share their thoughts and impressions as if they were the consumer of the app for the participants in the Patient group, or from their professional perspectives for the GP and Tech group participants. The full schedule of guiding questions for interviews and focus groups can be found in appendices A, B, and C. Phase 1 ceased once data saturation was reached, that is when no new information emerged from the last interview. Participants from phase one were then invited to join a focus group and discuss specific concepts or issues, in particular potential tensions between ethics principles that emerged from the phase one interviews. Participants were then invited to participate in phase three interviews to explore how their experience from the focus group had affected their views. The first author who facilitated the interviews and focus groups kept a journal logging her own views about the interview questions and the scenario, and reflection after each interaction with participants and each analysis.

2.2 Data analysis

Transcripts from the recordings were coded using NVivo 12 and MAXQDA2020. The ethics principles identified by Jobin et al. [6] and the CSIRO [21]Footnote 1 were used as a starting point for coding data that referred to or invoked ethics principles. Additional codes that were identified in the data were GP-patient relationship and health indicators. The data were also explored through the Critical Systems Heuristics (CSH) lens, resulting in consideration of further codes such as purpose, beneficiaries of the app, or custodians of the process (see full codebook in Suppl Appendix D). To begin analysis, interview transcripts were uploaded to NVivo. An initial interview from phase one was independently coded by three analysts and reviewed in a meeting. The boundaries and definitions of the ethics principles that formed the a priori codes were reviewed to check each reviewer’s interpretation, and additional codes were explored and discussed. The coding process was repeated with a second interview where the researchers reached a mutual agreement about boundaries and definitions associated with each code. One analyst then coded the remaining Phase 1 interview data in MAXQDA2020Footnote 2 based on the consensus. The generated codes fell under the following categories: ethics principles, GP-patient relationship, health indicators, AI, and ethics implementation. The number of co-occurrences between codes, that is the occurrences for one segment to be coded with several codes, were drawn to map out the relationships between ethics principles and other codes (see Fig. 4). The most frequent codes among ethics principles were autonomy and accountability, and they had the highest number of co-occurrences with other codes (see Table 1).

The most prominent themes that emerged from the analysis of the first set of interviews provided the basis of the discussions for the focus groups. These were autonomy, accountability, and GP-patient relationship. As such, the starting point of the discussions in each focus group was about how the ethics principles of autonomy and accountability can be at odds with each other, and their tensions with solidarity and dignity in each of the relationships of the GP-patient-AI system. Segments from phase 1 interviews that had co-occurrences with any the following: autonomy, accountability, GP-patient relationship, and health factors were extracted from the data. This subset and the focus group dataset were analysed together manually. Sources of motivation, power, knowledge, and legitimacy were examined, such as ‘who should be the guardian of the process or the data?’.

The phase 3 interviews were analysed manually, and separately from phase 1 and 2 data, to identify the emerging learning experiences of participants. The journal kept by the facilitator, and first author, provided insights about possible biases which were openly discussed among the researcher team. Some of the findings were congruent with the researchers’ expectations; some challenged their assumptions.

3 Results

The first author conducted eighteen individual interviews in phase 1 ranging in length from 45 to 90 min, three focus groups of 90 min duration in phase 2, and twelve 30-min interviews in phase 3, for a total of 30 h of audio-recordings. Six participants did not join the focus groups for availability reasons. Data collection took place over 5 months (13 April–9 September 2021). Each stakeholder group was represented in every focus group except in the third one (see Fig. 5). The stakeholders did not fall into neatly delineated groups. For example, one participant was a medical doctor and an AI developer hence being at the intersection of the AI technology and the GP group.

3.1 Participants

Eighteen participants (ten males, eight females) were recruited. Participants ranged from 23 to 82 years of age (M = 45 years, SD = 17.7). Participants provided written consent for inclusion in the study. Sixteen participants currently reside in Australia, ten live in urban centres, and six in semi-rural areas. Two participants, from the AI technology group, reside overseas. Seventeen of the 18 participants had a bachelor’s degree or higher level of education. A diversity of cultural and professional backgrounds were represented by the group of participants. The self-rated knowledge about AI technology of the participants spanned the whole spectrum from no knowledge at all to expert. See Table 2 for complete demographics of participants.

3.2 Themes—overview

Seven thematic domains emerged: (1) assumptions about health and the GP-patient relationship, (2) AIHA enhancing the GP-patient relationship, (3) overreliance on AI, (4) AIHA redistributes decision-making responsibility, (5) consumers’ AIHA knowledge, (6) AIHI data curation responsibility, and (7) consultation about AIHA as education. From phases one and two aggregated data, first, we explored the participants’ assumptions about health, the GP-patient relationship and how the AIHA is perceived as a solution for some issues within this relationship. While participants often expected the AIHA to compensate for some shortcomings within the GP-patient relationship, the possibility of overreliance on the new technology spelled fears of de-skilling and loss of context, narrowing visions at the individual, clinician, and policy maker levels. At the same time, AIHA was perceived to bring new knowledge that is affecting the autonomy and responsibility of the stakeholders’ decision-making process, as the knowledge can be empowering or a way to outsource accountability. Hence, it is important to understand how this new knowledge is communicated and whether its recipients are enabled to receive it. This then leads to questions of how this knowledge is curated, what is the quality of the information upon which it is based, how it is used and why, and who should be the custodians of the process. From phase 3 data, it appears that the consultative process itself was an educational experience for the participants.

3.3 Theme 1: assumptions about health and the GP-patient relationship

Autonomy, accountability, and trust were most often associated with the GP-patient relationship theme. The principle of autonomy in the GP-patient relationship plays a role in the patient’s perception of health and allows the patient to be responsible for her health:

I think it’s how [my GP’s] perception of health and wellbeing is really mine. She lets me be the driver of what is important to me, she only works on things that are important to me that I seek her out about. […] she’s one of the rare people in this space that allows me to drive on my health and wellbeing issue. (Patient/P10).

A free flow of questions between the GP and the patient can help with trust building (see Table 3, Patient/P1). Taking responsibility for a poor experience of a patient at the GP’s office helps build trust in the relationship (see Table 3, Patient/P4).

Autonomy and accountability were most frequently associated with health indicators. Health indicators expressed by participants included dimensions of well-being, and mental health such as “tranquillity” (Tech/P13), the relationship one has with one’s disease or condition (Patient/P6, P18), a sense of harmony with oneself and one’s surrounding (Patient/P18), or a sense of being part of a community (GP/P3, Patient/P2). One participant described it as “that sense of well-being, it’s not measuring any particular part of you or anything like that. It’s rather a whole concept” (Patient/P18).

GP/P3 characterised being healthy as “the resource to live meaningfully and in a control, like having a positive control over your own life” linking a sense of health to autonomy.

3.4 Theme 2: AIHA enhancing the GP-patient relationship

Another theme was how AI is perceived as a remedy for the deficiencies of the relationship between the GP and the patient. Time constraints for office visits, long waits (P4, P9, P7, P17), no consistent GP patient assignments (most patients plus GP-Tech P16, P12), and burden of clerical work (GP/P3, GP-Tech/P11 & P16) were invoked as contributors to the lack of satisfaction with the GP-patient relationship. The nature of the relationship was perceived by patients as changing and being less personal and more commercial than desired (see Table 4, Patient/P18).

Whereas for clinicians, a personal relationship over time with the patient is important for having a holistic approach (see Table 4, GP-Tech/P16), physicians’ mobility across practices can impede the development of such a relationship (see Table 4, GP-Tech/P16). Technology and clerical duties were also perceived by clinicians as impeding such a relationship: “That’s what we’ve done with technology, we turn doctors into clerical workers for at least half of their day and taken away the time to actually talk with their patients about health.” (GP-Tech/P11).

One expectation was that AI would alleviate the clerical burden, freeing time for better usage of office visits (see Table 4, GP-Tech P16). Another expectation was that for routine visits such as script renewal or simple issues, an AI would do this more conveniently without the constraints of having to make an appointment and lower the barriers to access care (see Table 4, Patient/P17).

AI was preferred in some circumstances because it was perceived as non-judgemental and due to the lack of rapport experienced by some with their GPs (GP-Tech P11, P17, and Focus Group 2). However, an AIHA helping a GP was seen as an opportunity for the GP to (re)develop empathy by allowing the GP to focus on the patient only (see Table 4, Tech/P15). The relationship with the GP was also suggested to contribute to the patient’s recovery (see Table 4, GP/P3).

3.5 Theme 3: overreliance on AI

While an AIHA could positively impact the GP-patient relationship, overreliance on the app was found to spell fears of a loss of autonomy and dignity for the consumer, loss of self-trust for GPs and patients, and deskilling of GPs. Most participants pondered whether a self-monitoring device could induce an overreliance on the signals from the device to the detriment of other physical self-observations or sensations even to the point of autosuggestion (see Table 5 Patient/P4, Patient/P10).

Most of the participants in the GP group reported a decreasing reliance on clinical examination and increasing reliance on tests for diagnosis and decisions on treatments over time as more technology becomes available:

GP practices changed in the last 10 years, particularly. [In the past], I’ll take a history during examination, and then decide what tests to do. The reverse is now true, that GPs, take a very brief history and then order tests. (GP/P12)

As the complexity of the tools and the difficulty of understanding the technology increase, concerns were expressed about how AI could accentuate the trend of increased reliance on technology for diagnosis and this could lead to the ‘dumbing down’ of medical training (see Table 5, GP/P2, Patient/P4).

At the public health agencies level, similarly, a concern was that an overreliance on automatic data collection would remove the data from their context and create a level of abstraction which can depersonalise the care process (see Table 5, Patient/P7).

3.6 Theme 4: AIHA redistributes decision-making responsibility

The information provided by the AIHA affects the decision-making process and potentially redistributes responsibilities between consumers and the AIHA. A concern voiced among the different groups was about the relevance and usefulness of the information provided by an AIHA. Two participants felt that if the AIHA does not answer a clear medical question, it is likely to create noise rather than clarity for the decision-making process for GPs and patients alike.

Various participants across all groups considered how the self-monitoring functionality could help individuals to increase their sense of control over their health and make more responsible decisions. Six participants expected that by being more aware of their health status, individuals would adapt their activities accordingly and be able to better care for themselves and their community. There was a concern though that by relying on an external device, the responsibility for one’s health would be outsourced to the device (see Table 6, Patient/P1). There was also a fear expressed that GPs would relinquish some of their responsibility to the AI (see Table 6, Patient/P18). A further concern raised was that, by outsourcing one’s responsibility for one’s health, one becomes akin to the AI system:

The worst side of that is that people just, you know, do follow along and, and don’t even think about what they’re doing. And, […] it can become, you know, the ultimate mechanized state where people just follow along the, the artificial intelligence to the point where they’re robotic themselves. (Patient/P6)

The concern expressed above applies to patients and clinicians alike. Conversely, two participants from patient group and one from the GP group thought that access to this kind of knowledge about one’s health could be empowering and help one connect the dots between behaviours, habits, and health impact. From GP/P3’s perspective, having access to regular information about the patient also helps with peace of mind. The AIHA gives more autonomy to the patient but also more responsibility for one’s health.

All participants agreed that an AIHA should only augment one’s decision-making process, and not override it. Yet, an example given by a participant from the Tech group of an AI embedded in a pacemaker that could act as a defibrillator if needed challenged this consensus. Additionally, three participants expressed a lack of trust in the human capability of decision-making, Patient/P5 remarking that an AIHA would be consistently biased, and as such more predictable than a human-based decision.

3.7 Theme 5: consumers’ AIHA knowledge

The AIHA gives access to new information to its consumers which can be empowering provided they can understand and interpret the information provided by the AIHA.

One issue was how to handle the situation when the AIHA’s diagnosis is not in agreement with the clinician’s. GP/P12 would keep investigating and did not see it as a novel issue (see Table 7, GP/P12) whereas another participant was more circumspect: “If you have another input of information that does not confirm your beliefs, then it’s going to be tricky to manage.” (GP-Tech/P16).

One participant from the GP group raised the question about the ability and competency required for an informed interpretation of the AIHA diagnosis or prognosis (see Table 7, GP/P3). Because such competency is from a field not traditionally part of medicine, there was a concern that developing such a competency could be to the detriment of clinical examination skills, overwhelming non-technology inclined GPs, and raise the barriers to access such types of service (see Table 7, Patient/P7).

One expectation was that AI could have an educational role. For example, it could help clinicians keep up to date (see Table 7, GP/P12). It could facilitate sharing collective knowledge among physicians, in effect disseminating a wealth of experience to any physician and possibly reducing biases from GPs (see Table 7, Patient/P5).

On the other hand, if a clinician is not equipped to correctly interpret the output of an AIHA, questions about informed consent, and clarity of shared decision-making were raised. One stated role of the physician was “to be informed decision makers or informed decision guides, people who can translate the science of medicine and the science of mental health into the realities that apply to your individual situation” (GP-tech/P11).

Regarding clinician’s communication of AI diagnosis, it was questioned whether a patient would be interested in knowing the process behind the diagnosis and presumed that it would be communicated in terms of possibilities and levels of accuracy of the algorithms. A parallel was drawn between communications about medical drugs to consumers and the importance of understanding where the information was coming from (see Table 7, Patient/P4).

While fully understanding how the AIHA came to a given conclusion was not deemed necessary, having the information available was perceived as important for feeling in control and making an informed decision (see Table 7, Patient/P6). Being transparent about limitations and principles could also help the process:

This is a tool. There will be doctors involved, there will be oversight, just to try and make it as transparent as possible. You can’t explain to people this is exactly how it works. It’s too complicated. But you can say these are the sorts of principles it’s based on: lots of information, looking at developing patterns, and those patterns […] being used to help make decisions. And I think people can generally understand that. (Patient/P17)

Participants proposed creating a new function dedicated to helping clinicians and patients interpret AIHA output within context (see Table 7, Patient/P18 & GP/P3). Yet, it was also noted that as an AIHA keeps learning (as suggested in the scenario), any informed consent would need to be renegotiable, and revisited regularly as the system evolves.

3.8 Theme 6: AIHA data curation responsibility

The AIHA introduces a novel source of information and knowledge for patients, clinicians, and health agencies alike which affects the responsibility and autonomy of each of them, and by proxy of the AI creators or generators. The AIHA’s output quality in part relies on the quality of the input data, hence the importance that participants understand who is responsible for the quality of the data, how it is collected and processed and by whom, and for what purpose.

3.8.1 Data quality

There were reservations about the quality of the data input. While participants in every group expressed some concerns, unsurprisingly it was mostly articulated by the participants in the Tech group who would prefer to have physicians enter data, as the GP would be more consistent in their interpretation of the symptoms (see Table 8, Tech/P8). One reason raised for the possible misrepresentation of symptoms by patients was to gain faster access to care by amplifying their severity (see Table 8, Tech/P8). However, there were some concerns raised as to whether the physicians have the time to capture such data:

Now, I know that machine learning, is supposed to enable us to become more and more finesse about an individual person. But that requires a lot of time to feed individual data in for every person, and if they need me to make another 15-minute appointment for my second issue. They certainly haven’t got time to put my uniqueness into an AI machine. (Patient/P18)

The AI developers are the ones cleaning and curating the data, and as such are responsible for their quality which needs to match the expectations or assumptions of the consumers of the AIHA (see Table 8, GP-tech/P11).

3.8.2 Data usage

A concern widely discussed during the study was data usage. A participant in the Tech-GP group highlighted the importance of considering how the generated information would be used in the context of the healthcare system:

So, what are we going to do with it? Just turn it loose on the world. So that that, you know, just those people who happen to have the right kind of watch now get early warning of COVID? Or are we going to turn it in to you know, something that is systematically useful? across the healthcare system? If you don’t have an answer to that question, you have no business building the thing. (GP-Tech/P11).

Another concern expressed was about how data could be repurposed for cross-selling services or drugs, which implied that participants assumed the AIHA was developed for profit (see Table 9, Patient/P1). A third concern, raised by three participants, was that data could be reused by governmental agencies and affect access to social services (see Table 9, Patient/P7). A fourth concern raised by four participants and in all the focus groups, was that the data could be used by insurance companies and affect premium prices. Though, Patient/P5 noted that the sector faces financial challenges and helping them stay afloat would benefit everyone.

A fifth concern voiced by a participant from the Tech group was about out-of-scope usage of the data such as extracting a case study from the data and turning it into a profiling tool (see Table 9, Tech/P15). A sixth concern was about the data possibly being used by health agencies to suit institutional, personal, or political agendas (see Table 9, Patient/P18). A seventh concern raised by three participants was about the usage of the data for surveillance of the population for nefarious purposes or surveilling GPs’ practices by monitoring their level of engagement with the technology (see Table 9, Patient/P18).

3.8.3 Sharing data as an act of solidarity

Because the scenario was about COVID-19, participants were willing to share their data out of solidarity or social responsibility, despite having trust issues. While there were some reservations about the data quality, and as such the safety of an AIHA especially in the early versions, data-sharing was seen as a long-term investment by some (see Table 10, Tech/P8).

Because such systems have the potential to create or improve access to care in remote areas, such as rural Australia or underprivileged countries, it is seen as an act of solidarity to donate one’s data for such systems to learn and even possibly to be a guinea pig for it—not unlike being part of a research study which was also evoked as a model by two participants and discussed in the first focus group (see Table 10, Patient/P18).

3.8.4 Data custodians

Data custodians and associated processes were discussed with participants. Unanimously and to the surprise of the facilitator, the participants would not trust government entities to be the custodians of the data, and less surprisingly neither would they trust a private commercial entity. While there was no definite scheme devised, it was agreed that the custodians of the data should be an independent organisation solely responsible for it, possibly a research institute with no other motives (P17), or possibly a cooperative scheme (P7). As noted previously, there was a sense that to make such an AIHA viable, it would have to involve a for-profit entity and as such, it was ineluctable that the data would be reused for commercial purposes. Given this environment, a health data brokerage could give more control over the usage of data into the hands of the originators (see Table 11, Patient/P7).

Regarding regulations, Tech/P13 shared that he would welcome regulatory guidelines to design an AIHA and alleviate his responsibility burden. Tech/P15 felt that regulations should address the scope of collected data as it could be broad and lead to exploitation for other purposes. The data custodians need “to know every detail and … and penalty behind misuse” (Tech/P15). Tech/P8 wanted the regulations to be ongoing given the dynamic nature of the technology to build trust in the system: “If we don’t have a continuous monitoring on those systems, I don’t think it will be possible to build that trust” (Tech/P8).

Patient/P18 suggested creating a new function looking at whether the system is doing what it says it was going to do, a sort of independent watchdog which would grant legitimization and trust supported by evidence from the system.

3.9 Theme 7: consultation about AIHA as education

The consultative process raised the awareness of all the participants about ethical issues to be considered. The twelve participants who went through the focus group experience reported in the individual exit interviews that the whole process offered them an opportunity to reflect on questions they had not thought about such as what health was for them and issues they had not previously considered about AI. Most participants also reported learning from their fellow participants. Tech/P13 reported how he had not realised how vulnerable patients were in their relationship to a clinician, or an AIHA. Because the process involved representatives of the different stakeholders, each participant had a chance to listen to views from a different vantage point and develop empathy. Through examples discussed in the focus groups, participants learned from the AI experts in the group about what AI does and does not do. Patient/P17 related how the experience boosted his confidence that AI can be designed and implemented ethically.

From the researcher’s point of view, the research raised awareness of the imbalance of knowledge between AI experts and AI consumers. Examples of applications, stories, and use cases helped serve both an educational purpose and a reflective purpose. While AI experts were eagerly listened to by other participants, it required a fine balance to allow for knowledge transfer while maintaining the integrity of the process which was egalitarian by design. As stated by a participant from the Tech group:

The public has to be informed in layman’s terms, but obviously so you know, you can keep on talking about artificial intelligence in layman terms, it’s fine for me. But the general public, somebody off the streets is not going to know what is artificial intelligence. Yeah, you could deceive them easily. (Tech/P15)

The consultative process is one opportunity to bring clarity and transparency to how ethics are implemented in the AIHA. It is also an enablement opportunity for all stakeholders.

4 Discussion

In this study, we sought to: (1) explore the assumptions, expectations, and perspectives of a range of stakeholders on the ethical issues associated with the introduction and use of an AIHA and the gaps and tensions between the expressed views, and (2) understand the influence of the consultative process on the participants’ understanding and views about the AIHA. To do so, we set up an inclusive and egalitarian consultative process where we explored the assumptions, expectations, and perspectives of a range of stakeholders of the clinician-patient-AIHA system about the use of AI in healthcare in relation to established ethics principles. We then assessed the gaps and tensions between these assumptions, expectations and perspectives and gained an understanding of the influence of the research process on the participants’ views and what they learned from the consultative experience. We found that ethics principles are often evoked in combination with each other, the GP-patient relationship and sense of health. This dynamic invites us to think in systems. Secondly, the AIHA was perceived by participants either as an enhancement to the GP-patient relationship, improving access to care or serving commercial interests. These conflicting expectations highlight the need for clarity of the purpose of the system. Thirdly, we identified how the introduction of an AIHA causes a redistribution of responsibility in the decision-making process among stakeholders who may or may not be ready to assume their share of responsibility. This requires us to consider how stakeholders are enabled to utilise the app. Fourthly, the thorny issues around data usage and possible infringement of users’ privacy were highlighted. This discussion led us to examine the possible and desirable custodians of the data. Finally, we consider how understanding the flow of information and knowledge could help identify ethical issues within stakeholders’ relationships, purposes, distribution of responsibility and enablement status of stakeholders, and data custodianship. By tying the four discussion points together, understanding the flow of information and knowledge brings clarity and transparency to the implementation of an ethics framework.

4.1 Considering relationships, thinking in systems

The first point that emerged from the study is how ethics principles are evoked in relation to each other, and in relation to the GP-patient relationship and the patient’s sense of health. It has implications for how an ethics framework is implemented at different levels. Most ethics frameworks come in the form of guidelines listing the different principles that need to be respected. The study findings suggest a need to consider the relationships between the principles. From an AI technology point of view, there are technical solutions developed to meet the requirements of one or two principles in isolation, such as privacy with federated learning techniques [23]. While the compartmentalisation of the issues to resolve can make them manageable, the study findings suggest the importance of considering the relationships between the principles. For example, the AI solution affects the sense of health and the GP-patient relationship even if tackling only one issue such as privacy. Ethics principles form a system, and there is a need to work on the coherence of the system, that is the optimal relationships within the system, rather than on each element separately.

If we consider the original diagram of the app presented to participants which featured the relationships between the AIHA and the consumers, in a star-shape fashion (see Fig. 1), other relationships that needed consideration emerged from the results (see Fig. 6). First, we found that the sense of health and wellbeing expressed by participants is not necessarily characterised by their medical data but rather their relationship with what the data tells them. We also found that the AIHA is expected to ease the relationship between the GP and the patient, leading to more patient autonomy. Yet, overreliance on the AIHA could also lead to a loss of autonomy of every stakeholder whether patient, clinician, or health agency. These findings concur with a survey conducted in the US [24]. It is therefore critical to consider how all the relationships are affected from an ethical point of view. A systems thinking approach focuses on relationships between elements of a system and using such an approach in healthcare is congruent with current research on complex systems [25]. Mapping the relationships between the elements of the system and identifying the ethical implications for each relationship brings clarity to the implementation of an ethics framework for an AIHA. When done in a participative process, it would add transparency and support to the discussions. This approach is used in SSM [12].

4.2 Clarifying purposes

Clarifying the purpose of the AIHA, and the primary beneficiaries, are important for developing an AI ethics framework. There were different purposes and primary beneficiaries that emerged in our study. For example, when looking at the GP-patient relationship, it was identified how the AIHA was perceived as a potential improvement to the shortcomings of the relationship. In primary care settings, relieving clerical and documentation duties and enabling patient self-management are among the issues that AI are expected to help with [26] and was also evoked in the study. While an AIHA may alleviate some autonomy issues like freeing up more time for the GP or providing more convenience to the patient, it does not necessarily address other causes of the dissatisfaction evoked in the study such as loss of rapport, or empathy in the GP-patient relationship. If the intent is to cut the cost of seeing patients by optimising the GP’s time through relief of clerical burden, the AIHA may not provide more individual consultation time for patients, but rather create more time slots for the GP to see more patients. Further, we found that usage of data collected by the AIHA appeared to be a major source of apprehension stemming from concerns that the data would be repurposed. The fear was that alternate purposes may not meet stakeholders’ values, or possibly be detrimental to them. This trust could be improved by providing transparency of the purpose of an AIHA and questioning whether the AIHA should be developed in the first place, as advocated in Reddy et al. [27]. Another observation from the study was how participants thought data were bound to be reused for commercial purposes. This is shaped by widespread models of commercial apps that exploit data impeding the imagination of alternative models. Making transparent who the AIHA is primarily serving—the patient, the GP, the health agency or the AIHA commercial entity for example—could be one step towards imagining alternatives as advocated in AI ethics circles [28]. Expanding the conversation to societal concerns, rather than limiting it to the AI technical design, is also a way to raise awareness of the ethical risks [29]. In our case, social responsibility involving sharing data out of solidarity without necessarily expecting a return in the immediate future was allowed to emerge through the study process, possibly primed by the COVID-19 context of the scenario. This illustrates how risk and trust could be balanced when considered in the context of the greater good. It also highlights the importance of transparency of purpose for this to happen, in this case, attached to the greater good. Each of these examples illustrates how clarity of purpose is a critical component of the implementation of an ethics framework.

4.3 Enabling stakeholders

The new source of information provided by the AIHA was perceived as empowering GP, patients, or health agencies to make more informed decisions. The study revealed that the way this information is delivered and used can affect the autonomy and sense of responsibility of the consumer of the information, which could also lead to one’s responsibility in the decision-making process being outsourced to the AIHA. Hence, all stakeholders must understand the scope and limitations of the AIHA. Some AI ethics frameworks advocate for educating developers about broader issues associated with the technology they develop, such as the French or Australian AI ethics framework initiatives [21, 30]. The need for GP education about the limitations and context of an AIHA has been raised by technology stakeholders [31,32,33], and it is part of the GP’s responsibility to be able to communicate clearly results from an AIHA to the patient [34]. However, the study suggests that patients’ education is important as well. Patients’ diversity of background and the complexity of the topic presents a challenge that may be addressed by embedding educational features in the AIHA when crafting the user experience. There are reflections about informed consent communications in the context of Big Data that offer interesting leads on how to enable consumers by using pictorials to make complex information more digestible [35]. Interestingly, we found that the process of bringing out individual and collective reflections from participants raised their level of awareness of certain issues, including their understanding of AI or lack thereof. As such, participatory processes in an AIHA design and implementation could be considered as an enablement exercise part of the how to implement ethics. This study strived to engage a diverse group of stakeholders blending AI experts and naïve participants in open dialogues in an egalitarian way not constrained by technical knowledge, and it made the main researcher and facilitator aware of her ethical responsibility in this endeavour. It was an enabling experience for her as well.

4.4 Identifying custodians

The dialogues in the study opened interesting avenues of inquiry about who should or could be the custodians of the data and the process to guarantee the integrity of the stated purpose of the app. Regulations and guidelines were welcomed by the Tech group, yet with the danger of becoming a way of outsourcing the app developer’s ethical responsibility. One model that emerged from the study is the creation of a neutral entity, possibly a research institute with no commercial interests in the application, who has required expertise, access to the data and how it is used and can take action to correct any issue. On the technology side, the gaps between proposed ethics guidelines and their implementation in an AI system that developers need to bridge have been well documented in the last 2 years [36, 37]. The translational tools are either too vague, making them prone to ethics washing, or too directive making them prone to context obliviating, which prompted the concept of ethics as a service, provided by a third party, to help balance the translational tools [36]. The data and process custodianship that emerged from the study appears to align with the ethics as a service concept especially in its requirement of being an ongoing process, not a one-off stamp of approval. The custodianship model from the study also appears to align with another theoretical approach akin to an ethics committee [29]. From a systems thinking perspective, by being a continuous process, this third-party element becomes part of the flow of knowledge coursing through the AIHA and a function of the system.

4.5 Understanding the flow of information and knowledge

Understanding the flow of information and knowledge going through the elements of the system brings transparency and clarity at different levels. As illustrated by the study’s results, every stakeholder is responsible for the information quality in the collection process. Whether stakeholders are aware of their responsibility or enabled to take it on is a question that needs to be examined. Understanding the flow of information and knowledge informs how responsibility could or should be distributed among stakeholders, and how the flow aligns with the purpose of the AIHA. Alteration of the flow and its content can be identified and examined, helping to determine the custodianship of the data. Such understanding could be used to guide the discussion in the consultative process. It is another model that brings clarity to the implementation of an ethics framework.

4.6 Limitations

The study involved a sample of eighteen participants. While striving for diversity, most of them were university educated. The data collection and most of the data analysis were completed by one researcher. To alleviate biases introduced by the researchers, a reflexive approach was adopted to make the biases transparent. Importantly, these limitations are likely to be found in any consultation-based approach to implementing an ethics framework. This makes this study reflexive of the process in nature and reinforces the need for a reflexive methodology.

5 Conclusion

While COVID-19 AI apps were developed rapidly to meet the challenges of the crisis, ethics should not be an afterthought, or remedial to prevent dire consequences down the line. The study findings point to a need for a systemic approach: identifying the purpose of the system, considering the relationships between the parts of the system, and mapping the flow of information and knowledge throughout the system. Because of the nature of AI, whose main resource is data, the mapping of the flow of knowledge has the potential to illuminate ethical issues holistically.

Data availability

All data relevant to the study are included in the article of uploaded as supplementary information.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Notes

While at the time of the study, the CSIRO Data 61 discussion paper was the reference used by the Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources of the Australian Government, a new set of Australia’s AI Ethics Principles have been published at the end of 2021 based on Ethically Aligned Design report by IEEE [22].

NVivo was available to all researchers, while MAXQDA2020 was only available to first author and chosen due to NVivo limitations on MacOS.

References

AAAS 2021: Artificial Intelligence and COVID-19: Applications and Impact Assessment. https://www.aaas.org/sites/default/files/2021-05/AIandCOVID19_2021_FINAL.pdf (2021)

Rahman, M.M., Khatun, F., Uzzaman, A., Sami, S.I., Bhuiyan, M.A.-A., Kiong, T.S.: A comprehensive study of artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches in confronting the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Int. J. Health Serv. 51(4), 446–461 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1177/00207314211017469

Marr, B.: The Top 5 Healthcare Trends in 2023 Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/bernardmarr/2022/12/06/the-top-5-healthcare-trends-in-2023/?sh=2e7f13b2565b (2022)

Cave, S., Whittlestone, J., Nyrup, R., hEigeartaigh, S.O., Calvo, R.A.: Using AI ethically to tackle covid-19. BMJ 372, n364 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n364

Leslie, D., Mazumder, A., Peppin, A., Wolters, M.K., Hagerty, A.: Does “AI” stand for augmenting inequality in the era of covid-19 healthcare? BMJ 372, n304 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n304

Jobin, A., Ienca, M., Vayena, E.: The global landscape of AI ethics guidelines. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1(9), 389–399 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-019-0088-2

Goirand, M., Austin, E., Clay-Williams, R.: Implementing ethics in healthcare AI-based applications: a scoping review. Sci. Eng. Ethics 27(5), 61 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-021-00336-3

Cawthorne, D., Wynsberghe, A.R.-V.: An ethical framework for the design, development, implementation, and assessment of drones used in public healthcare. Sci. Eng. Ethics 26(5), 2867–2891 (2020)

Ienca, M., Wangmo, T., Jotter, F., Kressig, R.W., Elger, B.: Ethical design of intelligent assistive technologies for dementia: a descriptive review. Sci. Eng. Ethics 24(4), 1035–1055 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-9976-1

Klein, B., & Schlömer, I.: A robotic shower system: acceptance and ethical issues. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 51(1), 25–31 (2018). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5775365/pdf/391_2017_Article_1345.pdf

Peters, D., Vold, K., Robinson, D., Calvo, R.A.: Responsible AI-two frameworks for ethical design practice. IEEE Trans. Technol. Soc. 1(1), 34–47 (2020)

Checkland, P., Poulter, J.: Soft systems methodology. In: Reynolds, M., Holwell, S. (eds.) Systems Approaches to Making Change: A Practical Guide, pp. 201–253. Springer London, London (2020)

Ulrich, W., Reynolds, M.: Critical systems heuristics: the idea and practice of boundary critique. In: Reynolds, M., Holwell, S. (eds.) Systems Approaches to Making Change: A Practical Guide, pp. 255–306. Springer London, London (2020)

Alvesson, M., Sköldberg, K.: Reflexive Methodology: New Vistas for Qualitative Research, 3rd edn. SAGE Publications, London (2018)

Sim, J., Saunders, B., Waterfield, J., Kingstone, T.: Can sample size in qualitative research be determined a priori? Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol.Methodol. 21(5), 619–634 (2018)

Marshall, B., Cardon, P., Poddar, A., Fontenot, R.: Does sample size matter in qualitative research?: a review of qualitative interviews in is research. Int. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 54(1), 11–22 (2013)

Hennink, M., Kaiser, B.N.: Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: a systematic review of empirical tests. Soc Sci Med 292, 114523 (2022)

Alavi, A., Bogu, G.K., Wang, M., Rangan, E.S., Brooks, A.W., Wang, Q., Snyder, M.P.: Real-time alerting system for COVID-19 and other stress events using wearable data. Nat. Med. 28, 175–184 (2022)

Lyons, S.: 2018 Using Self-Monitoring Apps to Care for Patients with Mild Cases of COVID-19 ABC Health & Wellbeing ABC. https://www.abc.net.au/news/health/2020-09-30/self-monitoring-mobile-apps-covid-19-patients-technology/12710652. Accessed 24 Feb 2021 (2021).

ZOE: COVID Symptom Study. https://covid.joinzoe.com. Accessed 24 Feb 2021 (2020)

Dawson, D., Schleiger, E., Horton, J., MacLaughlin, J., Robinson, C., Quezada, G., Hajkowicz, S.: Artificial Intelligence: Australia’s Ethics Framework. https://consult.industry.gov.au/strategic-policy/artificial-intelligence-ethics-framework/supporting_documents/ArtificialIntelligenceethicsframeworkdiscussionpaper.pdf (2019).

Australia’s Artificial Intelligence Ethics Framework: https://www.industry.gov.au/data-and-publications/australias-artificial-intelligence-ethics-framework/australias-ai-ethics-principles (2021).

Xu, J., Glicksberg, B.S., Su, C., Walker, P., Bian, J., Wang, F.: Federated learning for healthcare informatics. J. Healthc. Inform. Res. 5(1), 1–19 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41666-020-00082-4

Tyson, A., Pasquini, G., Spencer, A., & Funk, C.: 60% of Americans Would be Uncomfortable with Provider Relying on AI in Their Own Health Care. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2023/02/22/60-of-americans-would-be-uncomfortable-with-provider-relying-on-ai-in-their-own-health-care/ (2023).

Braithwaite, J.: Changing how we think about healthcare improvement. BMJ 361, k2014–k2014 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2014

Kueper, J.K., Terry, A., Bahniwal, R., Meredith, L., Beleno, R., Brown, J.B., Lizotte, D.J.: Connecting artificial intelligence and primary care challenges: findings from a multi stakeholder collaborative consultation. BMJ Health Care Inform. 29(1), e100493 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjhci-2021-100493

Reddy, S., Rogers, W., Makinen, V.-P., Coiera, E., Brown, P., Wenzel, M., Kelly, B.: Evaluation framework to guide implementation of AI systems into healthcare settings. BMJ Health Care Inform. 28(1), e100444 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjhci-2021-100444

Crawford, K.: The Atlas of AI Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. Yale University Press, New Haven (2021)

Hagendorff, T.: Blind spots in AI ethics. AI Ethics (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-021-00122-8

Villani, C. For a Meaningful Artificial Intelligence: Towards a French and European Strategy. Retrieved from Aiforhumanity.fr. https://www.aiforhumanity.fr/pdfs/MissionVillani_Report_ENG-VF.pdf (2018)

Abràmoff, M.D., Tobey, D., Char, D.S.: Lessons learned about autonomous AI: finding a safe, efficacious, and ethical path through the development process. Am. J. Ophthalmol.Ophthalmol. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2020.02.022

Rajkomar, A., Hardt, M., Howell, M.D., Corrado, G., Chin, M.H.: Ensuring fairness in machine learning to advance health equity. Ann. Intern. Med. 169(12), 866–872 (2018)

Sand, M., Duran, J.M., Jongsma, K.: Responsibility beyond design: physicians’ requirements for ethical medical AI. Bioethics 36, 1–8 (2021)

Holm, S.: Handle with care: assessing performance measures of medical AI for shared clinical decision-making. Bioethics 36(2), 178–186 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12930

Andreotta, A.J., Kirkham, N., Rizzi, M.: AI, big data, and the future of consent. AI Soc. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-021-01262-5

Morley, J., Elhalal, A., Garcia, F., Kinsey, L., Mökander, J., Floridi, L.: Ethics as a service: a pragmatic operationalisation of AI ethics. Minds Mach. (Dordr) 31(2), 239–256 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-021-09563-w

Morley, J., Floridi, L., Kinsey, L., Elhalal, A.: From what to how: an initial review of publicly available AI ethics tools, methods and research to translate principles into practices. Sci. Eng. Ethics 26(4), 2141–2168 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-019-00165-5

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Wendy Rogers for her thoughtful reviews of the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. MG is the recipient of an International Project Specific Macquarie University Research Excellence Scholarship (iMQRES).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MG, EA, RC-W conceived the study, MG conducted the individual interviews and focus groups. MG undertook the qualitative analysis. MG wrote the manuscript. EA, RC-W revised the first draft of the paper and the final draft. All authors approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Consent to participate

This project was approved by the Faculty of Medicine, Health, and Human Sciences Low-risk Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) at Macquarie University (project reference no. 52021978426391). Participants were required to sign a consent form to participate in focus groups and interviews.

Consent for publication

Not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Goirand, M., Austin, E. & Clay-Williams, R. Bringing clarity and transparency to the consultative process underpinning the implementation of an ethics framework for AI-based healthcare applications: a qualitative study. AI Ethics (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-024-00466-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-024-00466-x