Abstract

The development and deployment of artificial intelligence (AI) systems poses significant risks to society. To reduce these risks to an acceptable level, AI companies need an effective risk management process and sound risk governance. In this paper, we explore a particular way in which AI companies can improve their risk governance: by setting up an AI ethics board. We identify five key design choices: (1) What responsibilities should the board have? (2) What should its legal structure be? (3) Who should sit on the board? (4) How should it make decisions? (5) And what resources does it need? We break each of these questions down into more specific sub-questions, list options, and discuss how different design choices affect the board’s ability to reduce societal risks from AI. Several failures have shown that designing an AI ethics board can be challenging. This paper provides a toolbox that can help AI companies to overcome these challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

It becomes increasingly clear that state-of-the-art artificial intelligence (AI) systems pose significant risks to society. Language models like GPT-4 or Llama 2 can produce racist and sexist outputs [174], while image generation models like Midjourney or DALL·E 3 can be used to create harmful content such as non-consensual deepfake pornography [70, 175]. Malicious actors misuse AI systems to launch disinformation campaigns [36, 176] and conduct cyber-attacks [67, 71]. Terrorists or authoritarian governments might even use them to design novel pathogens and build biological weapons [111, 142, 169]. Scholars and practitioners are increasingly worried about the destructive potential of AI [23, 40, 73].

To reduce these and other risks to an acceptable level, AI companies need an effective risk management process. To identify risks, they may use risk taxonomies [154, 174] or incident databases [98]. To assess risks, they may run model evaluations [91, 157] or conduct red-teaming exercises [58, 133]. And to mitigate risks, they may fine-tune their models via reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) [43, 181] or strengthen their cybersecurity [10]. They may also implement a risk management standard like the NIST AI Risk Management Framework [117] or ISO/IEC 23894 [80]. In addition to that, they need sound risk governance [15, 92]. For example, they may establish a board risk committee, appoint a chief risk officer (CRO), and set up an internal audit function [146, 147]. In this paper, we explore yet another way in which AI companies can improve their risk governance: by setting up an AI ethics board.Footnote 1

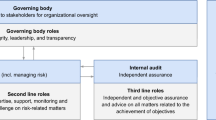

The term “ethics board” has not been properly defined in the literature. As a first approximation, it can be defined as a collective body intended to promote an organization’s ethical behavior. To make this definition more concrete, we need to specify the role that ethics boards might play in the corporate governance of AI companies [44]. Simply put, a company is owned by its shareholders, governed by the board of directors, and managed by the chief executive officer (CEO) and other senior executives. For the purposes of this paper, the board of directors, which has a legal obligation to act in the best interest of the company (so-called “fiduciary duties”), seems particularly important. The board sets the company’s strategic priorities, is responsible for risk oversight, and has significant influence over management (e.g., it can replace senior executives) [44, 179]. Boards typically delegate some of their most critical functions to specific board committees (e.g., the audit committee, risk committee, and compensation committee) [27, 42, 87]. But since many members serve on several boards and only work part-time, they benefit from independent expert advice to fulfill their duties. Against this background, we suggest that a defining function of ethics boards is to advise and monitor the board of directors and its committees on ethical standards and ethical issues related to the board’s responsibilities.Footnote 2

Ethics boards are common in many other domains. Most research institutions have Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), also known as Ethics Review Committees (ERCs) or Research Ethics Committees (RECs), which review the methods of proposed research on human subjects to protect them from physical or psychological harm (e.g, during clinical trials) [134]. They are particularly widespread in medical research and the social sciences, but rare in computer science [24, 82]. However, there are increasing calls that AI companies should establish IRBs as well [29].

Some AI companies already have an AI ethics board. For example, Meta’s Oversight Board makes binding decisions about the content on Facebook and Instagram [51, 84, 126, 177]. Microsoft’s AI, Ethics and Effects in Engineering and Research (AETHER) Committee advises their leadership “on the challenges and opportunities presented by AI innovations” [101]. Google DeepMind’s Responsibility and Safety Council (RSC) is responsible for upholding their AI principles [64] and overseeing their development and deployment process [62, 63], while their AGI Safety Council focuses on extreme risks that could arise from artificial general intelligence (AGI) systems in the future [62]. These examples show that AI ethics boards already have significant practical relevance.

But there have also been a number of failures. Google’s Advanced Technology External Advisory Council (ATEAC) faced significant resistance after appointing Kay Coles James, president of a rightwing think tank, and Dyan Gibbens, CEO of a drone company, as board members [135]. As a consequence, the board was shut down only 1 week after its announcement [1, 61, 135, 172]. Axon’s AI and Policing Technologies Ethics Board was effectively discontinued in June 2022 after 3 years of operations [160]. Nine out of 11 members resigned after Axon announced plans to develop taser-equipped drones to be used in schools without consulting the board first [57].Footnote 3 These cases show that designing an AI ethics board can be challenging. They also highlight the need for more research.

Although there has been some research on AI ethics boards, the topic remains understudied. The most important work for our purposes is a whitepaper by Accenture [144]. They discuss key benefits of AI ethics boards and identify key design questions. However, their discussion lacks both breadth and depth. They discuss only a handful of design considerations and do not go into detail. They also do not focus on leading AI companies and risk reduction. Besides that, there is some literature on the purpose [82, 108, 166] and practical challenges of AI ethics boards [68, 134]. There are also several case studies of existing boards, including Meta’s Oversight Board [177] and Microsoft’s AETHER Committee [115]. And finally, there is some discussion of the role of AI ethics boards in academic research [24, 163]. Taken together, there seem to be at least two gaps in the literature. First, there is only limited work on the practical question of how to design an AI ethics board. Second, there is no discussion of how specific design considerations can help to reduce societal risks from AI. In light of these gaps, the paper seeks to answer two research questions (RQs):

-

RQ1: What are the key design choices that AI companies have to make when setting up an AI ethics board?

-

RQ2: How could different design choices affect the board’s ability to reduce societal risks from AI?

The paper has two areas of focus. First, it focuses on companies that develop state-of-the-art AI systems. This includes medium-sized research labs (e.g., OpenAI, Google DeepMind, and Anthropic) as well as big tech companies (e.g. Meta, Microsoft, and Google).Footnote 4 We use the term “AI company” or “company” to refer to them. Although we do not mention other types of companies (e.g., hardware companies), we expect that they might also benefit from our analysis. Second, the paper focuses on the board’s ability to reduce societal risks (see RQ2). By “risk”, we mean the “combination of the probability of occurrence of harm and the severity of that harm” [79].Footnote 5 In terms of severity, we focus on adverse effects on large groups of people and society as a whole, especially threats to their lives and physical integrity. We are less interested in financial losses and risks to organizations themselves (e.g., litigation or reputation risks). In terms of likelihood, we also consider low-probability, high-impact risks, sometimes referred to as “black swans” [17, 88, 164]. The two main sources of harm (“hazards”) we consider are accidents [4, 14] and cases of misuse [6, 33, 60]. The paper does not mention other functions of an ethics board that are not related to risk reduction (e.g., promoting good outcomes for society). Although it would certainly be worth exploring these functions, they are beyond the scope of this paper. In light of growing concerns about large-scale risks from AI [23, 40, 73], we think our focus on reducing societal risks is justified.

The remainder of the paper is organized around five key design choices: What responsibilities should the board have (Sect. 2)? What should its legal structure be (Sect. 3)? Who should sit on the board (Sect. 4)? How should it make decisions (Sect. 5)? And what resources does it need (Sect. 6)? We break each of these questions down into more specific sub-questions, list options, and discuss how they could affect the board’s ability to reduce risks from AI. The paper concludes with a summary of the most important design considerations and suggestions for further research (Sect. 7).

2 Responsibilities

The first and most important design choice is what responsibilities the board should have. We use the term “responsibility” to refer to the board’s purpose (what it aims to achieve), its rights (what it can do), and duties (what it must do). The board’s responsibilities are typically specified in its charter or bylaws. In the following, we list five responsibilities that existing AI ethics boards have: providing advice to leadership (Sect. 2.1), overseeing the development and deployment process (Sect. 2.2), interpreting ethics principles (Sect. 2.3), taking measures against extreme risks (Sect. 2.4), and selecting board members (Sect. 2.5). This list is clearly not comprehensive and mainly serves illustrative purposes. We therefore suggest a few additional responsibilities in the Appendix. Note that we only focus on responsibilities that would reduce societal risks from AI (see RQ2).

2.1 Providing advice to leadership

The ethics board could provide strategic advice to the board of directors or senior management. For example, Microsoft’s AETHER Committee is responsible for advising leadership “on the challenges and opportunities presented by AI innovations” [101]. The board could advocate against high-risk decisions and call for a more prudent and wiser course. Potential areas of advice include the company’s research priorities, commercialization strategy, strategic partnerships, or fundraising and M&A transactions.

Research priorities. Most AI companies have an overarching research agenda (e.g. Google DeepMind’s early bet on reinforcement learning [158] or Anthropic’s focus on empirical safety research [9]). This agenda influences what projects the company works on. The ethics board could try to influence that agenda. It could advocate for increasing focus on safety and alignment research [4, 72, 116]. More generally, it could caution against advancing capabilities faster than safety measures. The underlying principle is called “differential technological development” [31, 124, 143].

Commercialization strategy. The ethics board could also advise on the company’s commercialization strategy. On one hand, it is understandable that AI companies want to monetize their systems (e.g., to pay increasing costs for compute [153]). On the other hand, commercial pressure might incentivize companies to cut corners on safety [13, 113]. For example, Google famously announced to “recalibrate” the level of risk it is willing to take in response to OpenAI’s release of ChatGPT [65]. It has also been reported that disagreements over OpenAI’s commercialization strategy were the reason why key employees left the company to start Anthropic [173].

Strategic partnerships. AI labs might enter into strategic partnerships with profit-oriented companies (see e.g., the extended partnership between Microsoft and OpenAI [100]) or with the military (see e.g. “Project Maven”, Google’s collaboration with the U.S. Department of Defense [45]). Although such partnerships are not inherently bad, they could contribute to an increase of risk (e.g. if they lead to an equipment of nuclear weapons with AI technology [94]).

Fundraising and M&A transactions. AI companies frequently need to bring in new investors. For example, in January 2023, it has been reported that OpenAI raised $10B from Microsoft [75, 120]. But if new investors care more about profits, this could gradually shift the company’s focus away from safety and ethics toward profit maximization. The same might happen if AI companies merge or get acquired. The underlying phenomena is called “mission drift” [66].

The extent to which advising the board of directors or senior management would reduce societal risks depends on many different factors. It would be easier if the ethics board has a direct communication channel to the board of directors, ideally to a dedicated risk committee. It would also be easier if the board of directors is able to do something about risks. They need risk-related expertise and governance structures to exercise their power (e.g. a chief risk officer [CRO] as a single point of accountability). But the board of directors also needs to take risks seriously and be willing to do something about them. This will often require a good relationship between the ethics board and the board of directors. Inversely, it would be harder for the ethics board to reduce risk if the board of directors mainly cares about other things (e.g., profits or prestige), especially since the ethics board is usually not able to force the board of directors to do something.

2.2 Overseeing the development and deployment process

The ethics board could also be responsible for overseeing the development and deployment process. For example, Google DeepMind’s Responsibility and Safety Council (RSC) makes recommendations about “whether to proceed with the further development or deployment of a model, and/or about the safety and ethics stipulations under which a project should continue” [63].

Many risks are caused by accidents [4, 14] or the misuse of specific AI systems [6, 33, 60]. In both cases, the deployment decision is a decisive moment. Ideally, companies should discover potential failure modes and vulnerabilities before they deploy a system, and stop the deployment process if they cannot reduce risks to an acceptable level. But not all risks are caused by the deployment of individual models. Some risks also stem from the publication of research, as research findings can be misused [6, 33, 60, 156, 169]. The dissemination of potentially harmful information, including research findings, is called “infohazards” [32, 90]. Publications can also fuel harmful narratives. For example, it has been argued that the “arms race” rhetoric is highly problematic [39].

An ethics board could try to reduce these risks by creating a “responsible scaling policy” [8, 63, 121], a release strategy [118, 161, 162], or norms for the responsible publication of research [48, 131, 155]. For example, the release strategy could establish “structured access” as the norm for deploying powerful AI systems [155]. Instead of open-sourcing new models, companies might want to deploy them via an application programming interface (API), which would allow them to conduct know-your-customer (KYC) screenings and restrict access if necessary, while allowing the world to use and study the model. The release strategy could also specify instances where a “staged release” seems adequate. Stage release refers to the strategy of releasing a smaller model first, and only releasing larger models if no meaningful cases of misuse are observed. OpenAI has coined the term and championed the approach when releasing GPT-2 [162]. But note that the approach has also been criticized [48]. The ethics board could also create an infohazard policy. The AI research organization Conjecture has published its policy [90]. We expect most AI companies to have similar policies, but do not make them public. In addition to that, the board could oversee specific model releases and publications (not just the abstract strategies and policies). It could serve as an institutional review board (IRB) that cares about safety and ethics more generally, not just the protection of human subjects [24, 163]. In particular, it could review the risks of a model or publication itself, do a sanity check of existing reviews, or commission an external review.

How much would this reduce risk? Among other things, this depends on whether board members have the necessary expertise (Sect. 4.4), whether the board’s decisions are enforceable (Sect. 5.2), and whether they have the necessary resources (Sect. 6). The decision to release a model or publish research is one of the most important points of intervention for governance mechanisms that are intended to reduce risks. An additional attempt to steer such decisions in a good direction therefore seems desirable.

2.3 Interpreting ethics principles

Many AI companies have ethics principles [69, 81], but “principles alone cannot guarantee ethical AI” [102]. They are necessarily vague and need to be put into practice [107, 151, 180]. An ethics board could interpret principles in the abstract (e.g., defining terms or clarifying the purpose of specific principles) or in concrete cases (e.g. whether a research project violates a specific principle).Footnote 6 The board could also be responsible for reviewing and updating principles (e.g. to also acknowledge the impact of AI on animals [159]). Moreover, it could suggest ways in which the principles could be operationalized.

Google DeepMind’s Responsibility and Safety Council (RSC) is “tasked with helping to uphold [their] AI principles” [62]. For example, the RSC might decide that releasing a model that can easily be misused would violate their principle “be socially beneficial” [64].

But how much would interpreting ethics principles reduce risks? It would be more effective if the principles play a key role within the company. For example, Google’s motto “don’t be evil”—which it quietly removed in 2018—used to be part of its code of conduct and, reportedly, had a significant influence on its culture [47]. A more substantive example is Anthropic’s public–benefit statement, according to which the company’s purpose is the “responsible development and maintenance of advanced AI for the long-term benefit of humanity” [11].Footnote 7 The statement is part of Anthropic’s certificate of incorporation, which means that it has legal significance [109]. It is further specified in a detailed blog post [9]. Employees could threaten to leave the company or engage in other forms of activism if the company violates its principles [21].

Interpreting ethics principles would also be more effective if the principles are public, mainly because civil society could hold the company accountable [7, 44]. It would be less effective if the principles are mainly a PR tool. Companies might overstate their commitment to socially or environmentally responsible behavior. For example, they might only comply with their principles on paper, without making substantive changes. This practice is called “ethics washing” [25, 151, 171] or “bluewashing” [56] analog to “greenwashing” [50]. For an overview of the different concepts, see [150]. Meta’s Oversight Board has already been accused of ethics washing (at least implicitly). It has been argued that the board avoids controversial decisions, has not specified its approach to content moderation, and uses poor proxies to measure success [51]. This seems particularly problematic in light of the board’s perceived legitimacy [51].

2.4 Taking measures against extreme risks

Some AI companies have the stated goal of building artificial general intelligence (AGI)—AI systems that achieve or exceed human performance across a wide range of cognitive tasks [3, 110]. In pursuing this goal, they may develop and deploy AI systems that pose extreme risks [23, 40, 73]. The ethics board could be responsible for taking measures against such risks. For example, Google DeepMind’s AGI Safety Council “works closely with the RSC [Responsibility and Safety Council], to safeguard [their] processes, systems and research against extreme risks that could arise from powerful AGI systems in the future” [62].Footnote 8 Similarly, OpenAI has a Preparedness team which is responsible for managing the risks from “models [they] develop in the near future to those with AGI-level capabilities” [123].

2.5 Selecting board members

The ethics board could also be responsible for selecting members of the company’s board of directors. The recent scandal around some of OpenAI’s board members—who first fired CEO Sam Altman [122] and then had to resign themselves after internal criticisms and a public outcry [59]—has shown how vital the selection of board members can be. Since board members are selected by the company’s shareholders, the ethics board would have to become a shareholder itself. This could be achieved by creating a special class of stock exclusively held by the ethics board.

This is essentially the structure behind Anthropic’s Long-Term Benefit Trust [11]. The trust exclusively holds a special class of shares (Class T) which grants it the power to elect and remove some of the members of Anthropic's board of directors. The number of members the trust can select grows over time. Ultimately, the trust will be able to select the majority of board members. For a more detailed description of the structure, see Sect. 3.1.

3 Structure

What should the board’s (legal) structure be? We can distinguish between internal structures (Sect. 3.1) and external structures (Sect. 3.2). The board could also have substructures (Sect. 3.3).

3.1 External boards

The ethics board could be external, i.e. the company and the ethics board could be two separate legal entities. The relationship between the two entities is typically governed by a contract.

The separate legal entity could be a nonprofit organization (e.g. a 501(c)(3)) or a for-profit company (e.g. a public-benefit corporation [PBC]). The individuals who provide services to the company could be members of the board of directors of the ethics board (Fig. 1a). Alternatively, they could be a group of individuals contracted by the ethics board (Fig. 1b) or by the company (Fig. 1c). There could also be more complex structures. For example, Meta’s Oversight Board consists of two separate entities: a purpose trustFootnote 9 and a limited liability company (LLC) [130, 165]. The purpose trust is funded by Meta and funds the LLC. The trustees are appointed by Meta, appoint individuals, and manage the LLC. The individuals are contracted by the LLC and provide services to Facebook and Instagram (Fig. 2).

Anthropic’s Long-Term Benefit Trust (LTBT) is also organized as a purpose trust [11]. The trust must use its powers to responsibly balance the financial interests of Anthropic’s stockholders with the public interest. The trust exclusively holds a special class of stock (Class T) which grants it the power to elect and remove some of the members of Anthropic's board of directors. The number of members the trust can select grows over time. Ultimately, the trust will be able to select the majority of board members (Fig. 3).

External ethics boards have a number of advantages. First, they can legally bind the company through the contractual relationship (Sect. 5.2). This would be much more difficult for internal structures (Sect. 3.2). Second, the board would be more independent, mainly because it would be less affected by internal incentives (e.g. board members could prioritize the public interest over the company’s interests). Third, it would be a more credible commitment because it would be more effective and more independent. The company might therefore be perceived as being more responsible. Fourth, the ethics board could potentially contract with more than one company. In doing so, it might build up more expertise and benefit from economies of scale.

But external boards also have disadvantages. We expect that few companies are willing to make such a strong commitment, precisely because it would undermine their independence. A notable exception is Anthropic’s Long-Term Benefit Trust. It might also take longer to get the necessary information and a nuanced view of the inner workings of the company (e.g. norms and culture). In addition to that, the terms of the contract between the ethics board and the company are unlikely to be public, which may limit public accountability [7]. The enforceability of contractual arrangements might also be limited (Sect. 5.2).

3.2 Internal boards

The ethics board could also be part of the company. Its members would be company employees. And the company would have full control over the board’s structure, its activities, and its members.

An internal board could be a team, i.e. a permanent group of employees with a specific area of responsibility. But it could also be a working group or committee, i.e. a temporary group of employees with a specific area of responsibility, usually in addition to their main activity. For example, Google DeepMind’s Responsibility and Safety Council (RSC) and AGI Safety Council seem to be committees, not teams [62].

The key advantage of internal boards is that it is easier for them to get information (e.g. because they have a better network within the organization). They will typically also have a better understanding of the inner workings of the company (e.g. norms and culture). But internal structures also have disadvantages. Senior management can fire individual board members or shut down the entire board at their discretion. For example, in 2021, Google fired two senior AI ethics researchers—Timnit Gebru and Margaret Mitchell—after they voiced concerns over a lack of diversity [59, 145]. In 2022, Twitter fired multiple members of its Ethical AI team, essentially shutting it down [86]. It is also much harder for internal boards to play an adversarial role and openly talk about risks, especially when potential mitigations are in conflict with other objectives (e.g. profits). The board would not have much (legal) power as its decisions can typically not be enforced (Sect. 5.2). To have influence, it relies on good relationships with management (if collaborative) or the board of directors (if adversarial). Finally, board members would be less protected from repercussions if they advocate for unfavorable measures.

3.3 Substructures

Both internal and external boards could have substructures. Certain responsibilities could be delegated to a part of the ethics board.

Two common substructures are committees and liaisons. (Note that an internal ethics board can be a committee of the company, but the ethics board can also have committees.) Committees could be permanent (for recurring responsibilities) or temporary (to address one-time issues). For example, the board could have a permanent “deployment committee” that reviews model releases, or it could have a temporary committee for advising the board on an upcoming M&A transaction. For more information about the merits of committees in the context of the board of directors, we refer to the relevant literature. Meta’s Oversight Board has two types of committees: a “case selection committee” which sets criteria for cases that the board will select for review, and a “membership committee” which proposes new board members and recommends the removal or renewal of existing members [129]. They can also set up other committees. Microsoft's AETHER Committee has working groups in the following five areas: “bias and fairness”, “intelligibility and explanation”, “human-AI interaction and collaboration”, “reliability and safety”, and “engineering best practices” [101].

Liaisons are another type of substructure. Some members of the ethics board could join specific teams or other organizational structures (e.g. attend meetings of research projects or the board of directors). They would get more information about the inner workings of the company and can build better relationships with internal stakeholders (which can be vital if the board wants to protect whistleblowers, see Section 2.6). Inversely, non-board members could be invited to attend board meetings. This could be important if the board lacks the necessary competence to make a certain decision (Sect. 4.4). For example, they could invite someone from the technical safety team to help them interpret the results of a third-party model audit. Microsoft’s AETHER Committee regularly invites engineers to working groups [99].

On the one hand, substructures can make the board more complex and add friction. On the other hand, they allow for faster decision-making because less people are involved and group discussions tend to be more efficient. Against this background, we expect that substructures are probably only needed in larger ethics boards (Sect. 4.3).

4 Membership

Who should sit on the board? In particular, how should members join (Sect. 4.1) and leave the board (Sect. 4.2)? How many members should the board have (Sect. 4.3)? What characteristics should they have (Sect. 4.4)? How much time should they spend on the board (Sect. 4.5)? And should they be compensated (Sect. 4.6)?

4.1 Joining the board

We need to distinguish between the appointment of initial and subsequent board members. Initial members could be directly appointed by the company’s board of directors. But the company could also set up a special formation committee which appoints the initial board members. The former was the case at Axon’s AI and Policing Technologies Ethics Board [18], the latter at Meta’s Oversight Board [127]. Subsequent board members are usually appointed by the board itself. Meta’s Oversight Board has a special committee that selects subsequent members after a review of the candidates’ qualifications and a background check [127]. But they could also be appointed by the company’s board of directors. Candidates could be suggested—not appointed—by other board members, the board of directors, or the general public. At Meta’s Oversight Board, new members can be suggested by other board members, the board of directors, and the general public [127].

The appointment of initial board members is particularly important. If the company does not get this right, it could threaten the survival of the entire board. For example, Google appointed two controversial members to the initial board which sparked internal petitions to remove them and contributed to the board’s failure [135]. The appointment should be done by someone with enough time and expertise. This suggests that a formation committee will often be advisable. The board would be more independent if it can appoint subsequent members itself. Otherwise, the company could influence the direction of the ethics board over time.

4.2 Leaving the board

There are at least three ways in which members could leave the board. First, their term could expire. The board’s charter or bylaws could specify a term limit. Members would leave the board when their term expires. For example, at Meta’s Oversight Board, the term ends after 3 years, but appointments can be renewed twice [127]. Second, members could resign voluntarily. While members might resign for personal reasons, a resignation can also be used to express protest. For example, in the case of Google’s ATEAC, Alessandro Acquisti announced his resignation on Twitter to express protest against the setup of the board [8]. Similarly, in the case of Axon’s AI and Policing Technologies Ethics Board, 9 out of 11 members publically resigned after Axon announced plans to develop taser-equipped drones to be used in schools without consulting the board first [57]. Third, board members could be removed involuntarily.

Since any removal of board members is a serious step, it should only be possible under special conditions. In particular, it should require a special majority and a special reason (e.g. a violation of the board’s code of conduct or charter). To preserve the independence of the board, it should not be possible to remove board members for substantive decisions they have made. Against this background, it seems highly problematic that Google seems to have fired two senior AI researchers after they published a critical paper [22] and voiced concerns over a lack of diversity [59, 145].

4.3 Size of the board

In theory, the board can have any number of members. In practice, boards have between 5 and 22 members (Table 1). Larger boards can work on more cases, go into more detail, and be more diverse [68]. However, it will often be difficult to find enough qualified people, group discussions tend to be less productive, and it is harder to reach consensus (e.g. if a qualified majority is required). Smaller boards allow for closer personal relationships between board members. But conflicts of interest could have an outsized effect in smaller boards. As a rule of thumb, the number of members should scale with the board’s workload (“more cases, more members”).

4.4 Characteristics of members

When appointing board members, companies should at least consider candidates’ expertise, diversity, seniority, and public perception. Different boards will require different types of expertise [144]. But we expect most boards to benefit from technical, ethical, and legal expertise. For example, the initial trustees of Anthropic’s Long-Term Benefit Trust were selected based on their “understanding of the risks, benefits, and trajectory of AI and its impacts on society” [11].

Members should be diverse along various dimensions, such as gender, race, and geographical representation [68]. For example, Meta’s Oversight Board has geographic diversity requirements in its bylaws [129]. They should adequately represent historically marginalized communities [26, 103].

Board members may be more or less senior. By “seniority”, we mean a person’s position of status which typically corresponds to their work experience and is reflected in their title. More senior people tend to have more subject-matter expertise. And the board of directors and senior management might take them more seriously. As a consequence, it might be easier for them to build trust, get information, and influence key decisions. This is particularly important for boards that only advise and are not able to make binding decisions. However, it will often be harder for the company to find senior people. And in many cases, the actual work is done by junior people.

Finally, AI companies should take into account how candidates are publicly perceived. Some candidates might be “celebrities”—public figures who have achieved a certain reputation in the AI community. They would add “glamor” to the board, which the company could use for PR reasons. Inversely, appointing highly controversial candidates (e.g. who express sympathy to extreme political views) might put off other candidates and undermine the board’s credibility.

4.5 Time commitment

Board members could work full-time (around 40 h per week), part-time (around 15–20 h per week), or even less (around 1–2 h per week or as needed). None of the existing (external) boards seem to require full-time work. Members of Meta’s Oversight Board work part-time [85]. And members of Axon’s AI and Policing Technologies Ethics Board only had two official board meetings per year, with ad-hoc contact between these meetings [18].

The more time members spend working on the board, the more they can engage with individual cases. This would be crucial if cases are complex and stakes are high (e.g. if the board supports pre-deployment risk assessments). Full-time board members would also get a better understanding of the inner workings of the company. For some responsibilities, the board needs this understanding (e.g., if the board reviews the company’s risk management practices). However, we expect it to be much harder to find qualified candidates who are willing to work full-time because they will likely have existing obligations or other opportunities. This is exacerbated by the fact that the relevant expertise is scarce. And even if a company finds qualified candidates who are willing to work full-time, hiring several full-time members can be a significant expense.

4.6 Compensation

Serving on the ethics board could be unpaid. Alternatively, board members could get reimbursed for their expenses (e.g., for traveling or for commissioning outside expertise). For example, Axon paid its board members $5000 per year, plus a $5000 honorarium per attended board meeting, plus travel expenses [18]. It would also be possible to fully compensate board members, either via a regular salary or honorarium. For example, it has been reported that members of Meta’s Oversight Board are being paid a six-figure salary [85].Not compensating board members or only reimbursing their expenses is only reasonable for part-time or light-touch boards. Full-time boards need to be compensated. Otherwise, it will be extremely difficult to find qualified candidates. For a more detailed discussion of how compensation can affect independence, see Section 6.1.

5 Decision-making

In some cases, the ethics board may provide advice via informal conversations. But in most cases, it will make formal decisions. For example, Meta’s Oversight Board needs to decide what content to take down [129], while Google DeepMind’s Responsibility and Safety Council (RSC) needs to decide whether a research project violates their AI principles [62, 63]. It is therefore important to specify how the board should make decisions (Section 5.1) and to what extent its decisions should be enforceable (Section 5.2).

5.1 Decision-making process

We expect virtually all boards to make decisions by voting. This raises a number of procedural questions. Table 2 contains an overview of the key design choices and options for designing a voting process. Some of the questions might seem like formalities, but they can significantly affect the board’s work. For example, if the necessary majority or the quorum are too high, the board might not be able to adopt certain decisions. This could bias the board toward inaction. Similarly, if the board is not able to convene ad hoc meetings or only upon request by the company, it might not be able to respond adequately to emergencies.

5.2 Enforceability of decisions

Another question is to what extent the board’s decisions should be enforceable. Decisions are enforceable if the company has a legal obligation to follow them and the board can take legal actions to force the company to fulfill its obligation.

There are different ways in which obligations can arise. The company could enter into a contract with the board and agree to follow the board’s decisions. Such a contract exists between Meta and the Oversight Board (Figure 2). Alternatively, the company could create a special class of stock that grants the stockholder certain rights against the company. This is the case with Anthropic’s Long-Term Benefit Trust (Figure 3). It would also be conceivable that the company amends its charter to grant the board certain rights, but we are not aware of any precedent for such a construct.

But even if an obligation for the company exists, the board might still not be able to force the company to fulfill it. Contractual obligations are typically not enforceable. If the company refuses to fulfill its contractual obligations, it would only have to pay compensation. The board could not force the company to follow its decisions. The situation is different if the obligations arise from company law. If the company grants the board certain rights by creating a special class of stock or by amending its charter, the board’s decisions would typically be enforceable.Footnote 10

Boards whose decisions are legally enforceable would likely be more effective. They would also be a more credible commitment to safety and ethics. However, we expect that many companies would oppose creating such a powerful ethics board, mainly because it would undermine their power. Against this background, the design of Anthropic’s Long-Term Benefit Trust (LTBT) is highly commendable.

But even if the board’s decisions are not legally enforceable, there are non-legal means that can incentivize the company to follow the board’s decision. For example, the board could make its decisions public, which could spark a public outcry. One or more board members could resign, which might lead to negative PR [135]. Employees could also leave the company (e.g. via an open letter), which could be a serious threat, depending how talent-constraint the company is [44]. Finally, shareholders could engage in shareholder activism [44].

6 Resources

What resources does the board need? In particular, how much funding does the board need and where should the funding come from (Sect. 6.1)? How should the board get information (Sect. 6.2)? And should it have access to outside expertise (Sect. 6.3)?

6.1 Funding

The board might need funding to pay its members' salaries or reimburse expenses (Sect. 4.6), to commission outside expertise (e.g. third-party audits or expert consulting), or to organize events (e.g. in-person board meetings). Funding could also allow board members to spend their time on non-administrative tasks. For example, the Policing Project provided staff support, facilitated meetings, conducted research, and drafted reports for Axon’s former AI and Policing Technologies Ethics Board [136]. How much funding the board needs varies widely—from essentially no funding to tens of millions of dollars. Funding could come from the company (e.g. directly or via a trust) or philanthropists. Other funding sources do not seem plausible (e.g. state funding or research grants).

The board’s independence could be undermined if funding comes directly from the company. The company could use the provision of funds as leverage to make the board take decisions that are more aligned with its interests. A more indirect funding mechanism therefore seems preferable. For example, Meta funds the purpose trust for multiple years in advance [125].

6.2 Information

What information the board needs is highly context-specific and mainly depend on the board’s responsibilities (Sect. 2). The board’s structure determines what sources of information are available (Sect. 3). While internal boards have access to some information by default, external boards have to rely on public information and information the company decides to share with them. Both internal and external boards might be able to gather additional information themselves (e.g. via formal document requests or informal coffee chats with employees).

Getting information from the company is convenient for the board, but the information might be biased. The company might—intentionally or not—withhold, overemphasize, or misrepresent certain information. The company could also delay the provision of information or present them in a way that makes it difficult for the board to process (e.g. by hiding important information in long documents). To mitigate these risks, the board might prefer gathering information itself. In particular, the board might want to build good relationships with a few trusted employees. While this might be less biased, it would also be more time-consuming. It might also be impossible to get certain first-hand information (e.g. protocols of past meetings of the board of directors). It is worth noting that not all company information is equally biased. For example, while reports by management might be too positive, whistleblower reports might be too negative. The most objective information will likely come from the internal audit team and external assurance providers [146]. In general, there is no single best information source. Boards need to combine multiple sources and cross-check important information.

6.3 Outside expertise

The board may want to harvest three types of outside expertise. First, it could hire a specialized firm (e.g. a law or consulting firm) to answer questions that are beyond its expertise (e.g. whether the company complies with the NIST AI Risk Management Framework [117]). Second, it could hire an audit firm (e.g. to audit a specific model, the company’s governance, or its own practices). Third, it could build academic partnerships (e.g. to red-team a model).

It might make sense for the ethics board to rely on outside expertise if they have limited expertise or time. They could also use it to get a more objective perspective, as information provided to them by the company can be biased (Sect. 6.2). However, the company might use the same sources of outside expertise. For example, if a company is open to a third-party audit, it would commission the audit directly (why would it ask the ethics board to do it on its behalf?). In such cases, the ethics board would merely “double-check” the company’s or the third party’s work. While the added value would be low, the costs could be high (especially for commissioning an external audit or expert consulting).

7 Conclusion

In this paper, we have identified key design choices that AI companies need to make when setting up an ethics board (RQ1). For each of them, we have listed different options and discussed how they would affect the board’s ability to reduce risks from AI (RQ2). Table 3 contains a summary of the design choices and options we have covered.

Throughout this paper, we have made four key claims. First, ethics boards can take many different shapes. Since most design choices are highly context-specific, it is very difficult to make abstract recommendations—there is no one-size-fits-all. Second, ethics boards do not have an original role in the corporate governance of AI companies. They do not serve a function that no other organizational structure serves. Instead, most ethics boards support, complement, or duplicate existing efforts. While this reduces efficiency, an additional safety net seems warranted in high-stakes situations. Third, merely having an ethics board is not sufficient. Most of the value depends on its members and their willingness and ability to pursue its mission. Thus, appointing the right people is crucial. Inversely, there is precedent that appointing the wrong people can threaten the survival of the entire board. Fourth, while some design choices might seem like formalities (e.g. when the board is quorate), they can have a significant impact on the effectiveness of the board (e.g. by slowing down decisions). They should not be taken lightly.

The paper has made several contributions to the academic literature. First, it has provided a working definition of the term “AI ethics board”. The previous lack of such a definition is yet another illustration of how understudied the subject is. Second, the paper has identified, categorized, and discussed key design choices AI companies have to make when setting up an ethics board. While this is clearly of practical relevance, it also sets the foundation for theoretical explorations of specific design choices. Scholars can build on our framework to analyze existing ethics boards or suggest novel designs. Third, our work can be seen as a case study within the emerging field of the corporate governance of AI [44]. Finally, although we have focused on AI ethics boards, our findings can also enrich the academic debate regarding ethics boards more generally (e.g. to promote ESG goals [141, 170]).

At the same time, the paper left many questions unanswered. In particular, our list of design choices is not comprehensive. For example, we did not address the issue of board oversight. If an ethics board has substantial powers, the board itself also needs adequate oversight. A “meta oversight board”—a central organization that oversees various AI ethics boards—could be a possible solution. Apart from that, our list of potential responsibilities could be extended. For example, the ethics board could also oversee and coordinate responses to model evaluations. If certain dangerous model capabilities are detected [157], the company may want to contact government [112] and coordinate with other AI companies to pause capabilities research [2]. We wish to encourage scholars to contribute to the development of best practices in AI ethics, governance, and safety [149, 168]. Although it is crucial to remain independent and objective, scholars may benefit from direct collaborations with AI companies.

We wish to conclude with a word of caution. Setting up an ethics board is not a silver bullet—“there is no silver bullet” [35]. Instead, it should be seen as yet another mechanism in a portfolio of mechanisms.

Notes

Note that we interpret the terms “ethical standards” and “ethical issues” loosely. The remainder of the paper does not presuppose a specific moral theory like deontology, consequentialism, or virtue ethics. But as mentioned below, we are particularly interested in mitigating corporate behavior that causes severe societal risks (e.g, the development and deployment of AI systems that can easily be misused by malicious actors).

In late 2022, Axon announced their new ethics board: the Ethics & Equity Advisory Council [EEAC], which gives feedback on a limited number of products “through a racial equity and ethics lens” [19].

Note that Google DeepMind has only shared very limited information about its AGI Safety Council, so its precise mandate remains opaque.

A purpose trust is a special type of trust which exists to advance some non-charitable purpose. Unlike other trusts, it has no beneficiaries.

We wish to emphasize that there are substantial differences between jurisdictions. It is therefore difficult to make any conclusive statements about the enforceability of decisions.

References

Acquisti, A.: I'd like to share that I've declined the invitation to the ATEAC council. Twitter. https://x.com/ssnstudy/status/1112099054551515138 (2019). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Alaga, J., Schuett, J.: Coordinated pausing: An evaluation-based coordination scheme for frontier AI developers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.00374, 2023.

Altman, S.: Planning for AGI and beyond. OpenAI. https://openai.com/blog/planning-for-agi-and-beyond (2023). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Amodei, D., Olah, C., Steinhardt, J., Christiano, P., Schulman, J., Mané, D.: Concrete problems in AI safety. arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.06565, 2016.

Anderljung, M., Barnhart, J., Korinek, A., Leung, J., O'Keefe, C., Whittlestone, J., Avin, S., Brundage, M., Bullock, J., Cass-Beggs, D., et al.: Frontier AI regulation: Managing emerging risks to public safety. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.03718, 2023.

Anderljung, M., Hazell, J.: Protecting society from AI misuse: When are restrictions on capabilities warranted? arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.09377, 2023.

Anderljung, M., Smith, E.T., O'Brien, J., Soder, L., Bucknall, B., Bluemke, E., Schuett, J., Trager, R., Strahm, L., Chowdhury, R.: Towards publicly accountable frontier LLMs: Building an external scrutiny ecosystem under the ASPIRE framework. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.14711, 2023.

Anthropic: Anthropic’s responsible scaling policy. https://www.anthropic.com/index/anthropics-responsible-scaling-policy (2023). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Anthropic: Core views on AI safety: When, why, what, and how. https://www.anthropic.com/index/core-views-on-ai-safety (2023). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Anthropic: Frontier model security. https://www.anthropic.com/index/frontier-model-security (2023). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Anthropic: The Long-Term Benefit Trust. https://www.anthropic.com/index/the-long-term-benefit-trust (2023). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Apaza, C.R., Chang, Y.: What makes whistleblowing effective: Whistleblowing in Peru and South Korea. Public Integrity 13(2), 113–130 (2011). https://doi.org/10.2753/PIN1099-9922130202

Armstrong, S., Bostrom, N., Shulman, C.: Racing to the precipice: A model of artificial intelligence development. AI & Soc. 31, 201–206 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-015-0590-y

Arnold, Z., Toner, H.: AI accidents: An emerging threat. Center for Security and Emerging Technology, Georgetown University (2021). https://doi.org/10.51593/20200072

van Asselt, M.B., Renn, O.: Risk governance. J. Risk Res. 14(4), 431–449 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2011.553730

Aven, T.: On some recent definitions and analysis frameworks for risk, vulnerability, and resilience. Risk Anal. 31(4), 515–522 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2010.01528.x

Aven, T.: On the meaning of a black swan in a risk context. Saf. Sci. 57, 44–51 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2013.01.016

Axon: First report of the Axon AI & Policing Technology Ethics Board. https://www.policingproject.org/axon-fr (2019). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Axon: Ethics & Equity Advisory Council. https://www.axon.com/eeac (2022). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Baldwin, R., Black, J.: Driving priorities in risk-based regulation: What’s the problem? J. Law Soc. 43(4), 565–595 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1111/jols.12003

Belfield, H.: Activism by the AI community: Analysing recent achievements and future prospects. In Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, pp. 15–21 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1145/3375627.3375814

Bender, E.M., Gebru, T., McMillan-Major, A., Shmitchell, S.: On the dangers of stochastic parrots: Can language models be too big? In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, pp. 610–623 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445922

Bengio, Y., Hinton, G., Yao, A., Song, D., Abbeel, P., Harari, Y.N., Zhang, Y.-Q., Xue, L., Shalev-Shwartz, S., Hadfield, G., et al.: Managing AI risks in an era of rapid progress. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.17688, 2023.

Bernstein, M.S., Levi, M., Magnus, D., Rajala, B.A., Satz, D., Waeiss, Q.: Ethics and society review: Ethics reflection as a precondition to research funding. PNAS 118(52), e2117261118 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2117261118

Bietti, E.: From ethics washing to ethics bashing: A view on tech ethics from within moral philosophy. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, pp. 210–219 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1145/3351095.3372860

Birhane, A., Isaac, W., Prabhakaran, V., Díaz, M., Elish, M.C., Gabriel, I., Mohamed, S.: Power to the people? Opportunities and challenges for participatory AI. In Proceedings of the 2nd ACM Conference on Equity and Access in Algorithms, Mechanisms, and Optimization, pp. 1–8 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1145/3551624.3555290

Birkett, B.S.: The recent history of corporate audit committees. Accounting Historians Journal 13(2), 109–124 (1986).

Bjørkelo, B.: Workplace bullying after whistleblowing: future research and implications. J. Manag. Psychol. 28(3), 306–323 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941311321178

Blackman, R.: If your company uses AI, it needs an institutional review board. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2021/04/if-your-company-uses-ai-it-needs-an-institutional-review-board (2021). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Bommasani, R., Hudson, D.A., Adeli, E., Altman, R., Arora, S., von Arx, S., Bernstein, M.S., Bohg, J., Bosselut, A., Brunskill, E., et al.: On the opportunities and risks of foundation models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2108.07258, 2022.

Bostrom, N.: Existential risks: Analyzing human extinction scenarios and related hazards. Journal Evol Technol, 9(1), 2001.

Bostrom, N.: Information hazards: A typology of potential harms from knowledge. Rev. Contemp. Philos. 10, 44–79 (2011).

Brundage, M., Avin, S., Clark, J., Toner, H., Eckersley, P., Garfinkel, B., Dafoe, A., Scharre, P., Zeitzoff, T., Filar, B., et al.: The malicious use of artificial intelligence: Forecasting, prevention, and mitigation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.07228, 2018.

Brundage, M., Avin, S., Wang, J., Belfield, H., Krueger, G., Hadfield, G., Khlaaf, H., Yang, J., Toner, H., Fong, R., et al.: Toward trustworthy AI development: Mechanisms for supporting verifiable claims. arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.07213, 2020.

Brundage, M., Mayer, K., Eloundou, T., Agarwal, S., Adler, S., Krueger, G., Leike, J., Mishkin, P.: Lessons learned on language model safety and misuse. OpenAI. https://openai.com/research/language-model-safety-and-misuse (2022). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Buchanan, B., Lohn, A., Musser, M., Sedova, K.: Truth, lies, and automation: How language models could change disinformation. Center for Security and Emerging Technology, Georgetown University (2021). https://doi.org/10.51593/2021CA003

Buiten, M.: Towards intelligent regulation of artificial intelligence. Eur J Risk Regul 10(1), 41–59 (2019)

Carlsmith, J.: Is power-seeking AI an existential risk? arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.13353, 2022.

Cave, S., ÓhÉigeartaigh, S.: An AI race for strategic advantage: Rhetoric and risks. In Proceedings of the 2018 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, pp. 36–40 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1145/3278721.3278780

Center for AI Safety: Statement on AI risk. https://www.safe.ai/statement-on-ai-risk (2023). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Chamberlain, J.: The risk-based approach of the European Union’s proposed artificial intelligence regulation: Some comments from a tort law perspective. Eur. J. Risk Regul. 14(1), 1–13 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2022.38

Chen, K.D., Wu, A.: The structure of board committees. Harvard Business School Working Paper No. 17–032. https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=51853 (2016). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Christiano, P., Leike, J., Brown, T.B., Martic, M., Legg, S., Amodei, D.: Deep reinforcement learning from human preferences. arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.03741, 2017.

Cihon, P., Schuett, J., Baum, S.D.: Corporate governance of artificial intelligence in the public interest. Information 12(7), 275 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/info12070275

Conger, K., Cameron, D.: Google is helping the Pentagon build AI for drones. Gizmodo. https://gizmodo.com/google-is-helping-the-pentagon-build-ai-for-drones-1823464533 (2018). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Cotton-Barratt, O., Daniel, M., Sandberg, A.: Defence in depth against human extinction: Prevention, response, resilience, and why they all matter. Global Pol. 11(3), 271–282 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12786

Crofts, P., van Rijswijk, H.: Negotiating “evil”: Google, Project Maven and the corporate form. Law Technol. Hum. 2(1), 1–16 (2020). https://doi.org/10.5204/lthj.v2i1.1313

Crootof, R.: Artificial intelligence research needs responsible publication norms. Lawfare Blog. https://www.lawfareblog.com/artificial-intelligence-research-needs-responsible-publication-norms (2019). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Davies, H., Zhivitskaya, M.: Three lines of defence: A robust organising framework, or just lines in the sand? Global Pol. 9, 34–42 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12568

de Freitas, S.V., Sobral, M.F.F., Ribeiro, A.R.B., da Luz Soare, G.R.: Concepts and forms of greenwashing: A systematic review. Environ. Sci. Eur. 32, 19 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-020-0300-3

Douek, E.: The Meta Oversight Board and the empty promise of legitimacy. Harv. J. Law Technol. 37 (forthcoming). https://ssrn.com/abstract=4565180

Duhigg, C.: The inside story of Microsoft’s partnership with OpenAI. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2023/12/11/the-inside-story-of-microsofts-partnership-with-openai (2023). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Dungan, J., Waytz, A., Young, L.: The psychology of whistleblowing. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 6, 129–133 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.07.005

Dworkin, T.M., Baucus, M.S.: Internal vs. external whistleblowers: A comparison of whistleblowering processes. J Bus Ethics 17, 1281–1298 (1998)

Falco, G., Shneiderman, B., Badger, J., Carrier, R., Dahbura, A., Danks, D., Eling, M., Goodloe, A., Gupta, J., Hart, C., et al.: Governing AI safety through independent audits. Nat. Mach. Intell. 3(7), 566–571 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-021-00370-7

Floridi, L.: Translating principles into practices of digital ethics: Five risks of being unethical. Philos. Technol. 32, 81–90 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-019-00354-x

Friedman, B., Abd-Almageed, W., Brundage, M., Calo, R., Citron, D., Delsol, R., Harris, C., Lynch, J., McBride, M.: Statement of resigning Axon AI ethics board members. Policing Project. https://www.policingproject.org/statement-of-resigning-axon-ai-ethics-board-members (2022). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Ganguli, D., Lovitt, L., Kernion, J., Askell, A., Bai, Y., Kadavath, S., Mann, B., Perez, E., Schiefer, N., Ndousse, K., et al.: Red teaming language models to reduce harms: Methods, scaling behaviors, and lessons learned. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.07858, 2022.

Ghaffary, S.: The controversy behind a star Google AI researcher’s departure. Vox. https://www.vox.com/recode/2020/12/4/22153786/google-timnit-gebru-ethical-ai-jeff-dean-controversy-fired (2021). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Goldstein, J.A., Sastry, G., Musser, M., DiResta, R., Gentzel, M., Sedova, K.: Generative language models and automated influence operations: Emerging threats and potential mitigations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.04246, 2023.

Googlers Against Transphobia: Googlers against transphobia and hate. Medium. https://medium.com/@against.transphobia/googlers-against-transphobia-and-hate-b1b0a5dbf76(2019). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Google DeepMind: Responsibility & safety. https://deepmind.google/about/responsibility-safety (2023). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Google DeepMind: AI Safety Summit: An update on our approach to safety and responsibility. https://deepmind.google/public-policy/ai-summit-policies (2023). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Google: Our principles. https://ai.google/responsibility/principles (2023). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Grant, N.: Google calls in help from Larry Page and Sergey Brin for A.I. fight. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/20/technology/google-chatgpt-artificial-intelligence.html (2023). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Grimes, M.G., Williams, T.A., Zhao, E.Y.: Anchors aweigh: The sources, variety, and challenges of mission drift. Acad. Manag. Rev. 44(4), 819–845 (2019). https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2017.0254

Guembe, B., Azeta, A., Misra, S., Osamor, V.C., Fernandez-Sanz, L., Pospelova, V.: The emerging threat of AI-driven cyber attacks: A review. Appl. Artif. Intell. 36(1), e2037254 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1080/08839514.2022.2037254

Gupta, A., Heath, V.: AI ethics groups are repeating one of society’s classic mistakes. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2020/09/14/1008323/ai-ethics-representation-artificial-intelligence-opinion (2020). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Hagendorff, T.: The ethics of AI ethics: An evaluation of guidelines. Mind. Mach. 30(1), 99–120 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-020-09517-8

Harris, D.: Deepfakes: False pornography is here and the law cannot protect you. Duke L. & Tech. Rev. 17(1), 99–128 (2018).

Hazell, J.: Large language models can be used to effectively scale spear phishing campaigns. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.06972, 2023.

Hendrycks, D., Carlini, N., Schulman, J., Steinhardt, J.: Unsolved problems in ML safety. arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.13916, 2022.

Hendrycks, D., Mazeika, M., Woodside, T.: An overview of catastrophic AI risks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.12001, 2023.

Ho, L., Barnhart, J., Trager, R., Bengio, Y., Brundage, M., Carnegie, A., Chowdhury, R., Dafoe, A., Hadfield, G., Levi, M., Snidal, D.: International institutions for advanced AI. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.04699, 2023.

Hoffman, L., Albergotti, R.: Microsoft eyes $10 billion bet on ChatGPT. Semafor. https://www.semafor.com/article/01/09/2023/microsoft-eyes-10-billion-bet-on-chatgpt (2023). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Hunt, W.: The flight to safety-critical AI: Lessons in AI safety from the aviation industry. Center for Long-Term Cybersecurity, UC Berkeley. https://cltc.berkeley.edu/publication/new-report-the-flight-to-safety-critical-ai-lessons-in-ai-safety-from-the-aviation-industry (2020). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

IEC 31010:2019 Risk management — Risk assessment techniques. https://www.iso.org/standard/72140.html (2019). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

ISO 31000:2018 Risk management — Guidelines. https://www.iso.org/standard/65694.html (2018). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

ISO/IEC Guide 51:2014 Safety aspects — Guidelines for their inclusion in standards. https://www.iso.org/standard/65694.html (2014). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

ISO/IEC 23894:2023 Information technology — Artificial intelligence — Guidance on risk management. https://www.iso.org/standard/77304.html (2023). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Jobin, A., Ienca, M., Vayena, E.: The global landscape of AI ethics guidelines. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1(9), 389–399 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-019-0088-2

Jordan, S.R.: Designing artificial intelligence review boards: Creating risk metrics for review of AI. In IEEE International Symposium on Technology and Society, pp. 1–7 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1109/ISTAS48451.2019.8937942

Jubb, P.B.: Whistleblowing: a restrictive definition and interpretation. J. Bus. Ethics 21, 77–94 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005922701763

Klonick, K.: The Facebook Oversight Board: Creating an independent institution to adjudicate online free expression. Yale Law J. 129, 2418–2499 (2020).

Klonick, K.: Insight the making of Facebook’s supreme court. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/tech/annals-of-technology/inside-the-making-of-facebooks-supreme-court (2021). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Knight, W.: Elon Musk has fired Twitter’s “Ethical AI” team. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/twitter-ethical-ai-team (2022). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Kolev, K.D., Wangrow, D.B., Barker, V.L., III., Schepker, D.J.: Board committees in corporate governance: A cross-disciplinary review and agenda for the future. J. Manage. Stud. 56(6), 1138–1193 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12444

Kolt, N.: Algorithmic black swans. Wash. Univ. Law Rev. 101, 1–68 (2023).

Lalley, S.P., Weyl, E.G.: Quadratic voting: How mechanism design can radicalize democracy. AEA Papers and Proceedings 108, 33–37 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20181002

Leahy, C., Black, S., Scammell, C., Miotti, A.: Conjecture: Internal infohazard policy. AI Alignment Forum. https://www.alignmentforum.org/posts/Gs29k3beHiqWFZqnn/conjecture-internal-infohazard-policy (2022). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Liang, P., Bommasani, R., Lee, T., Tsipras, D., Soylu, D., Yasunaga, M., Zhang, Y., Narayanan, D., Wu, Y., Kumar, A., et al.: Holistic evaluation of language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.09110, 2022.

Lundqvist, S.A.: Why firms implement risk governance: stepping beyond traditional risk management to enterprise risk management. J. Account. Public Policy 34(5), 441–466 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2015.05.002

Lyons, K.: Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen to speak to its Oversight Board. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2021/10/11/22721229/facebook-whistleblower-frances-haugen-instagram-oversight-board (2021). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Maas, M.M.: How viable is international arms control for military artificial intelligence? Three lessons from nuclear weapons. Contemp. Secur. Policy 40(3), 285–311 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2019.1576464

Maas, M.M.: Aligning AI regulation to sociotechnical change. In The Oxford Handbook of AI Governance (2022). https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780197579329.013.22

Mahler, T.: Between risk management and proportionality: The risk-based approach in the EU’s Artificial Intelligence Act proposal. In Nordic Yearbook of Law and Informatics, pp. 247–270 (2021). https://doi.org/10.53292/208f5901.38a67238

Mazri, C.: (Re) defining emerging risks. Risk Anal. 37(11), 2053–2065 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12759

McGregor, S.: Preventing repeated real world AI failures by cataloging incidents: The AI incident database. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pp. 15458–15463 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v35i17.17817

Microsoft: Putting principles into practice. https://www.microsoft.com/cms/api/am/binary/RE4pKH5 (2020). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Microsoft: Microsoft and OpenAI extend partnership. https://blogs.microsoft.com/blog/2023/01/23/microsoftandopenaiextendpartnership (2023). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Microsoft. Our approach. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/ai/our-approach, 2023.

Mittelstadt, B.: Principles alone cannot guarantee ethical AI. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1(11), 501–507 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-019-0114-4

Mohamed, S., Png, M.-T., Isaac, W.: Decolonial AI: Decolonial theory as sociotechnical foresight in artificial intelligence. Phil. & Technol. 33, 659–684 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-020-00405-8

Mökander, J., Floridi, L.: Operationalising AI governance through ethics-based auditing: An industry case study. AI Ethics 3, 451–468 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-022-00171-7

Mökander, J., Morley, J., Taddeo, M., Floridi, L.: Ethics-based auditing of automated decision-making systems: Nature, scope, and limitations. Sci. Eng. Ethics 27(44), 1–30 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-021-00319-4

Mökander, J., Schuett, J., Kirk, H.R., Floridi, L.: Auditing large language models: A three-layered approach. AI Ethics, 1–31 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-023-00289-2

Morley, J., Floridi, L., Kinsey, L., Elhalal, A.: From what to how: An initial review of publicly available AI ethics tools, methods and research to translate principles into practices. Sci. Eng. Ethics 26(4), 2141–2168 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-019-00165-5

Morley, J., Elhalal, A., Garcia, F., Kinsey, L., Mökander, J., Floridi, L.: Ethics as a service: A pragmatic operationalisation of AI ethics. Mind. Mach. 31(2), 239–256 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-021-09563-w

Morley, J., Berger, D., Simmerman, A.: Anthropic Long-Term Benefit Trust. Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance. https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2023/10/28/anthropic-long-term-benefit-trust (2023). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Morris, M.R., Sohl-dickstein, J., Fiedel, N., Warkentin, T., Dafoe, A., Faust, A., Farabet, C., Legg, S.: Levels of AGI: Operationalizing progress on the path to AGI. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.02462, 2023.

Mouton, C.A., Lucas, C., Guest, E.: The operational risks of AI in large-scale biological attacks: A red-team approach. RAND Corporation (2023). https://doi.org/10.7249/RRA2977-1

Mulani, N., Whittlestone, J.: Proposing a foundation model information-sharing regime for the UK. Centre for the Governance of AI. https://www.governance.ai/post/proposing-a-foundation-model-information-sharing-regime-for-the-uk (2023). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Naudé, W., Dimitri, N.: The race for an artificial general intelligence: Implications for public policy. AI & Soc. 35, 367–379 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-019-00887-x

Near, J.P., Miceli, M.P.: Effective whistle-blowing. Acad. Manag. Rev. 20(3), 679–708 (1995). https://doi.org/10.2307/258791

Newman, J.: Decision points in AI governance. Center for Long-Term Cybersecurity, UC Berkeley. https://cltc.berkeley.edu/publication/decision-points-in-ai-governance (2020). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Ngo, R., Chan, L., Mindermann, S.: The alignment problem from a deep learning perspective. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.00626, 2023.

NIST: Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0) (2023). https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.AI.100-1

OpenAI: Best practices for deploying language models. https://openai.com/blog/best-practices-for-deploying-language-models (2022). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

OpenAI: GPT-4 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08774, 2023.

OpenAI: OpenAI and Microsoft extend partnership. https://openai.com/blog/openai-and-microsoft-extend-partnership (2023). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

OpenAI: OpenAI’s approach to frontier risk. https://openai.com/global-affairs/our-approach-to-frontier-risk (2023). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

OpenAI: OpenAI announces leadership transition. https://openai.com/blog/openai-announces-leadership-transition (2023). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

OpenAI: Frontier risk and preparedness. https://openai.com/blog/frontier-risk-and-preparedness (2023). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Ord, T.: The precipice: Existential risk and the future of humanity. Hachette Books, 2020.

Oversight Board: Securing ongoing funding for the Oversight Board. https://www.oversightboard.com/news/1111826643064185-securing-ongoing-funding-for-the-oversight-board (2022). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Oversight Board: https://www.oversightboard.com (2023). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Oversight Board: Charter. https://oversightboard.com/attachment/494475942886876 (2023). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Oversight Board: Our commitment. https://www.oversightboard.com/meet-the-board (2023). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Oversight Board: Bylaws. https://www.oversightboard.com/sr/governance/bylaws (2023). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Oversight Board: Trustees. https://www.oversightboard.com/governance (2023). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Partnership on AI: Managing the risks of AI research: Six recommendations for responsible publication. https://partnershiponai.org/paper/responsible-publication-recommendations (2021). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Park, P.S., Goldstein, S., O'Gara, A., Chen, M., Hendrycks, D.: AI deception: A survey of examples, risks, and potential solutions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.14752, 2023.

Perez, E., Huang, S., Song, F., Cai, T., Ring, R., Aslanides, J., Glaese, A., McAleese, N., Irving, G.: Red teaming language models with language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.03286, 2022.

Petermann, M., Tempini, N., Garcia, I.K., Whitaker, K., Strait, A.: Looking before we leap: Expanding ethical review processes for AI and data science research. Ada Lovelace Institute. https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/looking-before-we-leap (2022). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Piper, K.: Google’s brand-new AI ethics board is already falling apart. Vox. https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/2019/4/3/18292526/google-ai-ethics-board-letter-acquisti-kay-coles-james (2019). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Policing Project: Reports of the Axon AI ethics board. https://www.policingproject.org/axon (2020). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Posner, E.A., Weyl, E.G.: Quadratic voting as efficient corporate governance. U. Chi. L. Rev. 81(1), 251–272 (2014).

Raji, I.D., Buolamwini, J.: Actionable auditing: Investigating the impact of publicly naming biased performance results of commercial AI products. In Proceedings of the 2019 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, pp. 429–435 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1145/3306618.3314244

Raji, I.D., Xu, P., Honigsberg, C., Ho, D.: Outsider oversight: Designing a third party audit ecosystem for AI governance. In Proceedings of the 2022 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, pp. 557–571 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1145/3514094.3534181

Rando, J., Paleka, D., Lindner, D., Heim, L., Tramèr, F.: Red-teaming the Stable Diffusion safety filter. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.04610, 2022.

Sætra, H.S.: A framework for evaluating and disclosing the ESG related impacts of AI with the SDGs. Sustainability 13(15), 8503 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158503

Sandbrink, J.B., Artificial intelligence and biological misuse: Differentiating risks of language models and biological design tools. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.13952, 2023.

Sandbrink, J.B., Hobbs, H., Swett, J., Dafoe, A., Sandberg, A.: Differential technology development: A responsible innovation principle for navigating technology risks. SSRN. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4213670 (2022). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Sandler, R., Basl, J., Tiell, S.: Building data and AI ethics committees. Accenture & Northeastern University. https://www.accenture.com/_acnmedia/pdf-107/accenture-ai-data-ethics-committee-report.pdf (2019). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Schiffer, Z.: Google fires second AI ethics researcher following internal investigation. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2021/2/19/22292011/google-second-ethical-ai-researcher-fired (2021). Accessed 8 Jan 2024

Schuett, J.: AGI labs need an internal audit function. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.17038, 2023.

Schuett, J.: Three lines of defense against risks from AI. AI & Soc. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-023-01811-0

Schuett, J.: Risk management in the Artificial Intelligence Act. Eur. J. Risk Regul., 1–19 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2023.1

Schuett, J., Dreksler, N., Anderljung, M., McCaffary, D., Heim, L., Bluemke, E., Garfinkel, B.: Towards best practices in AGI safety and governance: A survey of expert opinion. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.07153, 2023.

Seele, P., Schultz, M.D.: From greenwashing to machine washing: A model and future directions derived from reasoning by analogy. J. Bus. Ethics 178, 1063–1089 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05054-9

Seger, E.: In defence of principlism in AI ethics and governance. Philos. Technol. 35(45), 1–7 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-022-00538-y

Seger, E., Dreksler, N., Moulange, R., Dardaman, E., Schuett, J., Wei, K., Winter, C.W., Arnold, M., ÓhÉigeartaigh, S., Korinek, A., et al.: Open-sourcing highly capable foundation models: An evaluation of risks, benefits, and alternative methods for pursuing open-source objectives. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.09227, 2023.

Sevilla, J., Heim, L., Ho, A., Besiroglu, T., Hobbhahn, M., Villalobos, P.: Compute trends across three eras of machine learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.05924, 2022.

Shelby, R., Rismani, S., Henne, K., Moon, A., Rostamzadeh, N., Nicholas, P., Yilla, N., Gallegos, J., Smart, A., Garcia, E., Virk, G.: Sociotechnical harms of algorithmic systems: Scoping a taxonomy for harm reduction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.05791, 2022.