Abstract

This paper examines the new AI control problem and the control dilemma recently formulated by Sven Nyholm. It puts forth two remarks that may be of help in (dis)solving the problem and resolving the corresponding dilemma. First, the paper suggests that the idea of complete control should be replaced with the notion of considerable control. Second, the paper casts doubt on what seems to be assumed by the dilemma, namely that control over another human being is, by default, morally problematic. I suggest that there are some contexts (namely, relations of vicarious responsibility and vicarious agency) where having considerable control over another human being is morally unproblematic, if not desirable. If this is the case, control over advanced humanoid robots could well be another instance of morally unproblematic control. Alternatively, what makes it a problematic instance remains an open question insofar as the representation of control over another human being is not sufficient for wrongness, since even considerable control over another human being is often not wrong.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The notion of control is philosophically underexplored in the AI ethics literature, despite being grave importance. Sven Nyholm makes important progress in exploring this theme in his recent AI and Ethics paper “A new control problem? Humanoid robots, artificial intelligence, and the value of control” [18] (he also responds to some objections in another paper on this topic, [19]). He formulates a new AI control problem and control dilemma, both of which undermine the frequent tacit assumption that controls over AI systems can only be a good, desirable thing.

The present paper first explains Nyholm’s new control problem and control dilemma. It then puts forth two remarks that may contribute towards (dis)solving the problem and resolving the dilemma. As a first remark, the paper suggests that the idea of complete control should be substituted by the notion of considerable control, since we do not and should not seek complete control, whether over AI or over any another (in some sense intelligent and autonomous) entity. Besides, the notion of considerable control is sufficient for generating the problem and for posing the corresponding dilemma. Second, the paper sheds doubt on what seems to be assumed by the dilemma, namely that control over another human being is, by default, morally problematic. This is achieved by considering the notions of vicarious responsibility and vicarious agency. Their relations are offered as examples of cases where considerable control is not problematic even in the case of human beings, such that it is unclear why it should be problematic in the case of advanced humanoid robots (and other potentially problematic cases of AI). While this is a far cry from completely solving the problem, if it is correct, it will help us to advance on the path towards solving it, whether by showing that advanced humanoid robots fall within the morally unproblematic cases of control over another or by further clarifying what the challenge consists in, namely explaining why considerable control over advanced humanoid robots should be viewed as more akin to problematic kinds of control over human beings than to unproblematic examples of such control.

1 Nyholm’s new control problem and control dilemma

In formulating the new AI control problem, Nyholm distinguishes it from the old control problem, which pertains to our loss of control over advanced AI systems. This loss of control may lead to existential risks, and it also seems to lead to gaps in responsibility (on the AI responsibility gaps debate, see, for instance, [2, 11, 13, 14, 17, 21, 22]). Simplifying grossly, the reasoning is as follows: responsibility requires control; some AI systems are such that no one has control over them; so no one is responsible for what such an AI does (the main source of simplification is that not all kinds of responsibility require control, so its alleged lack is not relevant to all potential responsibility gaps). Importantly, the old control problem and the related debate often tacitly assume that control over AI is always good and desirable. Nyholm then formulates a new control problem, which undermines precisely this assumption. The problem can be formulated as “the question of under what circumstances retaining and exercising complete control over robots and AI is unambiguously ethically good, and the challenge of separating those from circumstances under which there is something ethically problematic about wanting to have complete control over robots and AI” [2, 18].

In general, some kinds of control are good, but some are bad.Footnote 1 Nyholm notes that self-control is good, perhaps even non-instrumentally so. By contrast, control over other people is bad, perhaps even non-instrumentally so. If certain humanoid robots can be seen as persons or their representations, and control over them as being or representing control over another person, then such control would be a bad thing. Nyholm carefully wonders whether there are advanced humanoid robots that can be seen as representations of other persons, and control over them in turn as a representation of control over another person. However, perhaps, this much can be granted: we have already encountered worrisome real-life examples of people falling in love with chatbots and suffering from heartbreak and loss akin to losing a partner or a friend following a system update.Footnote 2 It thus seems that not even cutting-edge technology is perceived as a (representation of a) person. However, if that is the case, I have little doubt regarding whether a more advanced humanoid robot could be perceived as such. This seems to provide a reason for not wanting to have considerable (let alone full) control over such robots. Yet, it might be unsafe not to have control over such robots. Nyholm points out that what we are facing is a dilemma: “In relation to any AI agents which might be regarded as being or representing some form of persons, we could say that this does not only create a new control problem, but also a control dilemma. Losing control over these AI agents that appear to be some form of persons might be problematic or bad because it might be unsafe, on the one hand. Having control over these AI agents might be morally problematic because it would be, or represent, control over another person, on the other hand.” [8, 18] This could in turn motivate the claim that we should perhaps refrain from creating such robots altogether (e.g., by dropping the humanoid form, thereby avoiding the resemblance to people), or at least control these entities in a way that acknowledges the distastefulness at issue: “the best solution seems to be to avoid creating humanoid robots unless there is some very strong reason to do so that could help to outweigh the symbolic problems with having a humanoid robot that we are exercising complete control over. Or, alternatively, we might try to exercise control over these robots in a way that signals that we find it distasteful to do so, or that at least signals and acknowledges that we find it wrong to try to control real human beings.” [10, 18] Nyholm’s conclusion, if correct, has important practical consequences for the industry. While he is not suggesting a ban on advanced humanoid robots, he argues that it is preferable to avoid the humanoid form unless there are overriding reasons to develop such robots (as may well be the case when it comes to carebots). I would like to step back and examine whether these really are our only options.

2 First remark: we do not, and should not, seek complete control

What does it even mean to have complete control over someone or something? Nyholm does not define this difficult notion, but he makes it clear that the very concept of control is incredibly complex. The aim of the present section is to look more closely at the kind of control people seek when they want to control, whether problematically or not, another human being or an AI system.

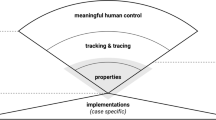

Starting with AI, its crucial advantage is that it allows us to do certain things in a more efficient way, or to achieve a better outcome than we would otherwise. Yet, some ways of achieving a better outcome, or of reaching a goal with greater efficiency, are not always morally acceptable, as the AI ethics literature points out (see, for instance, [4]). This makes us want, or even require, some degree of control over AI systems. For instance, we want AI to stay within the limits set by our values (such as fairness and safety, or whatever values have normative authority in the context at issue), and we want to be able to prevent undesirable outcomes (such as unfairness towards certain groups of people) and to interfere if needed (on the classic control problem and value alignment, see [5, 8]). On the other hand, if full control meant, for instance, having control over what AI does, when, how precisely, and with what exact outcome, such a control would fly in the face of most of the advantages of AI, if not also in the face of the very possibility of a robot or a system’s being in some sense autonomous and intelligent. The very desire to have such control does not sit well with the idea of current “black box” AI systems (see [15, 20]) (it is practically impossible to control every aspect of these AI systems at all times and under all circumstances) and with the promise of great efficiency, autonomy, (artificial) creativity, and (artificial) intelligence (even if it was possible to have complete control, it would undermine central features and advantages of AI). It seems that the control we want, and should want, to stay rational, is not full control but limited yet considerable control.

In addition, if the analogy is being made with the (supposedly morally problematic) desire to control people, then, here too, people do not want to have complete control. It is practically impossible to have complete control over another human being, at least if complete control means controlling every aspect of their behaviour at all times and under all circumstances. Additionally, even if such control were possible, exercising it would undermine central features of human life and human relationships. A jealous partner might want to control what their significant other wears, or with whom they meet or chat, but they would perhaps not want to control how they breathe, what exactly they utter, how often they blink, or the exact amount of cereal they eat for breakfast. Otherwise, controlling their significant other would be a 24/7 job, leaving time for nothing else. Here too, it seems that the person wants considerable, not full, control (though, in this case, they clearly should not have it).

We do not and should not want complete control, whether over another human being or an AI system, but this is so for reasons that are more basic than moral ones. First of all, it is practically (if not flat out) impossible to have complete control over such complex entities as human beings or advanced AI systems. Second, even if such control were possible, it would threaten central features of AI or human life and human relationships. What we sometimes want, however, is considerable control. While this notion is not explicated in the present paper, it can be pre-theoretically understood as control that is extensive and sufficiently robust in the given context, and that is all we need to formulate the new control problem and the corresponding dilemma.

3 Second remark: it is not always wrong to control another

Nyholm’s paper suggests that wanting to have control over another human being is bad. The question is whether it is always bad. Nyholm makes one concession in this regard in his second paper on the topic: “Children, for example, are persons, and it is morally permissible and perhaps even morally required for parents to exercise a certain amount of control over their children, at least when they are small. However, the older and more mature children get, the more problematic it becomes for parents to completely control their children” [11, 19]. Nyholm here claims that (small) children are persons. However, it is debatable whether they are full moral persons in the sense in which this notion is used in his papers. In addition, this quotation reveals that the notion of complete control is contentious even if applied to small children alone (as we can see, Nyholm concedes that it is morally permissible to exercise a certain amount of control, rather than complete control, over small children. And rightly so: for instance, we are now increasingly aware that it is not a good idea to force small children to smile, hug, or kiss when commanded.Footnote 3 Nonetheless, this example is helpful, because it is a counterexample to the general thesis that it is always wrong to control other human beings. I would like to take a further step and show that this kind of control is in fact often morally unproblematic and that there are many cases beyond those involving small children in which this is so. To see this, consider relations of vicarious responsibility and vicarious agency. Here is a (by no means exhaustive) list of such relations:

the employer-employee relation

the parent-child relation

the teacher-pupil relation

the general-soldier relation

the leader of a political party-party member relation

the principal investigator-member of a research team relation

the dean-head of department relation

the head of department-department member relation

Vicarious responsibility is a primarily legal doctrine that makes room for taking responsibility for the actions of others. This “taking responsibility” normally takes the form of compensation. In a similar vein, vicarious agency is a concept that allows for extended agency: if one issues a command to another and that other person does as they are commanded, the action can be vicariously attributed to the commanding person. Vicarious agency is sometimes even taken as a basis for vicarious responsibility, but as Giliker argues, this unnecessarily conflates both notions and makes vicarious responsibility a form of direct personal responsibility, which it is not (see [9]). For the purposes of this paper, it is not necessary to properly delineate which examples can be subsumed under the relations of vicarious responsibility and which under those of vicarious agency (on this distinction, and on the given two notions, see for instance [1, 9, 10]).

Both vicarious responsibility relations and vicarious agency relations give rise to types of control over other human beings that are not morally problematic and can even be desirable, expected, good, if not also required. This is because it is desirable, expected, good, and also required of us that we fulfil the role responsibilities associated with the roles we take on (such as being a principal investigator or a head of department) and that we fulfil them well. Fulfilling these roles well in turn requires some form of control over subordinates. Note, however, that this is not to say that the superordinate entity cannot abuse their power and overstep the boundaries of appropriate control; the point is merely that there are plenty of examples where exercising considerable control over another is a good thing. Let us look more closely at some of the above examples and at what an appropriate level of control would look like. For instance, parents are expected to raise their children, to teach them the moral values of their society (or of humanity), to oversee their children, and to prevent harm done to or caused by them. To give another example, the principal investigator of an academic project should ensure that the members of the research team are working on the project, that they are meeting the declared goals of the project and delivering the deliverables, that they are meeting the standards of the academic community, that they acknowledge the project’s funding, and so forth.

In all these examples, considerable control over another is a good thing, and even essential to the proper functioning of these roles. In a similar vein, it is not wrong to want to have such a control; quite on the contrary: it is good and it shows a responsible attitude towards the roles we occupy, and towards the role responsibilities they give rise to. However, the same cannot be said of complete control: the control is certainly limited to the given role, and the authority it grants. Moreover, there is a further motivation to drop complete control even within a given role and speak of considerable control instead: as Magnet points out in [16], in a highly professionalized work environment, it is no longer wise to assume that employers can fully control how employees execute the tasks delegated to them, and thus practically impossible to prevent all harms that can be caused by employees.

4 Concluding remarks: towards (dis)solving the problem

If the two points made in the above remarks are granted, namely that we want considerable control over AI, and that it is not always wrong to want to have considerable control over another human being or a representation of another human being, the core question is where the case of us wanting to have considerable control over an advanced humanoid robot would fall—would we resemble a toxic partner, or would we resemble a reasonable employer or parent? More generally, we are facing two options: either advanced humanoid robots as such fall within the morally unproblematic cases of control over another or they fall within the category of morally problematic cases of control over another.

If the former turns out to be the case, that is, if advanced humanoid robots as such fall within the morally unproblematic cases of control over another, the problem will be very close to being solved and the dilemma resolved. Can an advanced humanoid robot be seen as a relatum in a similar relation between a (in some sense) superordinate entity and a (in that sense) subordinate entity? Can the control exercised by the superordinate entity over an advanced humanoid robot be of the appropriate kind for this relation? As a matter of fact, AI has been described as involving similar relations, namely the vicarious responsibility or vicarious agency of an owner, user, manufacturer, or programmer (cf. [2, 3, 7, 12, 23]).Footnote 4

Note, however, that this option alone does not automatically mean that all kinds of considerable control are morally unproblematic. As pointed out in the preceding section, the relations of vicarious responsibility and vicarious agency provide a basis for considerable control, but only within certain limits. An employer may want to interfere and make sure that you are doing your work correctly; a parent may protect you from suffering or causing harm, or force you to do your homework; a teacher can prevent you from smoking in the classroom or from engaging in academic dishonesty, and so forth. However, an employer should not interfere with your religious beliefs, or with the way you spend your free time; a parent should not force you to eat licorice or drink alcohol; a teacher should not make you befriend a classmate you cannot stand, and they certainly should not make you bully another classmate, and so forth. Determining the precise sphere of acceptable and desirable control is not a trivial task (this could be seen as having some relation to [11, 19]). Equally untrivial is determining the parallel sphere of acceptable and desirable control over advanced humanoid robots. It might be helpful to think of the limits of competence, or the purpose of the given role in each case. For example, it is completely acceptable, even desirable, to have considerable control over an emotional support humanoid robot within the limits of the purposes for which that robot was manufactured, for example to make sure that it is really therapeutic, and thus fulfilling its main purpose, that it is physically safe, that it will not lead to a different kind of psychological harm, and so forth. On the other hand, it would likely be neither desirable nor acceptable to, for example, force the robot to have sex with you, to harm other people, to utter slurs, or to destroy itself. This also helps to explain why it would not be acceptable to let people control autonomous vehicles, such that they abruptly stop in the middle of the road, thereby risking an accident (see Yampolskiy’s example, discussed by Nyholm [5, 18]).

If the latter is the case, that is, if advanced humanoid robots as such fall within the category of morally problematic cases of control over another, the above remarks will still be helpful in advancing on the path towards dissolving the problem and resolving the dilemma by further clarifying what the challenge consists in: in particular, the challenge amounts to explaining why exercising considerable control over advanced humanoid robots should be more akin to problematic kinds of considerable control over human beings (e.g., the control exercised by a toxic partner or a manipulative so-called friend) rather than being akin to morally unproblematic kinds of such control (e.g., the considerable control exercised by an employer or a manager over an employee, a parent or teacher’s control over a child, a dean’s control over a head of department, or a principal investigator’s control over the members of their research team). If we opt for this route, it may be helpful to ask who the “patient” of responsibility is (cf. [6]), along with related questions with which I wish to close the paper, as a prompt for those who are unsatisfied with the above, former option: Who are we concerned about, and why? Are we concerned about the person who wants to have considerable control over an advanced humanoid robot? If so, is this because wanting such control makes them a bad person? Or are we concerned about the robot itself? If so, is this because the robot itself is worthy of moral consideration (an option that Nyholm does not prefer but that others might consider)? Or is this perhaps a concern about other members of the human population (an option Nyholm finds plausible in his second paper; see [11, 12, 19])? If so, is this, apart from the symbolic reasons stressed by Nyholm, because the agent who wants to control an advanced humanoid robot might cultivate their controlling tendencies and attempt to control those around them?

Notes

Note that Nyholm does not explicate the notions “morally good” and “morally bad”; nor does he suggest what the truth-makers of moral truths are or commit to an ethical or a metaethical view. This approach is advantageous as it allows for generality.

See, for instance, the following Washington Post article https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2023/03/30/replika-ai-chatbot-update/.

An interesting open question raised by the referee concerns whether advanced humanoid robots could be seen as delegating control voluntarily or whether this is entirely unfeasible.

References

Glavaničová, D., Pascucci, M.: Making sense of vicarious responsibility: moral philosophy meets legal theory. Erkenntnis 1–22 (2022)

Glavaničová, D., Pascucci, M.: Vicarious liability: a solution to a problem of AI responsibility? Ethics Inf. Technol. 24(3), 28 (2022)

Asaro, P.M.: A body to kick, but still no soul to damn: legal perspectives on robotics. In: Lin, P., Abney, K., Bekey, G.A. (eds.) Robot Ethics: The Ethical and Social Implications of Robotics, pp. 169–186. MIT Press, Cambridge (2012)

Bostrom, N.: Ethical issues in advanced artificial intelligence. Cogn. Emot. Ethical Asp. Decis. Mak. Hum. 2, 12–17 (2003)

Bostrom, N.: Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2014)

Coeckelbergh, M.: Artificial intelligence, responsibility attribution, and a relational justification of explainability. Sci. Eng. Ethics 26(4), 2051–2068 (2020)

Chesterman, S.: We, the Robots? Regulating Artificial Intelligence and the Limits of the Law. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2021)

Gabriel, I.: Artificial intelligence, values, and alignment. Minds Mach. 30(3), 411–437 (2020)

Giliker, P.: Vicarious Liability in Tort: A Comparative Perspective. Cambridge University Press, New York (2010)

Gray, A.: Vicarious Liability: Critique and Reform. Hart Publishing, Oxford (2018)

Gunkel, D.J.: Mind the gap: responsible robotics and the problem of responsibility. Ethics Inf. Technol. 22, 307–320 (2020)

Gurney, J.: Applying a reasonable driver standard to accidents caused by autonomous vehicles. In: Lin, P., Abney, K., Jenkins, R. (eds.) Robot Ethics 2.0, pp. 51–65. Oxford University Press, New York (2017)

Kiener, M.: Can we bridge AI’s responsibility gap at Will? Ethical Theory Moral Pract. 25(4), 575–593 (2022)

Köhler, S., Roughley, N., Sauer, H.: Technologically blurred accountability? Technology, responsibility gaps and the robustness of our everyday conceptual scheme. In: Ulbert, C., Finkenbusch, P., Sondermann, E., Debiel, T. (eds.) Moral agency and the politics of responsibility, pp. 51–68. Routledge, London (2017)

London, A.J.: Artificial intelligence and black-box medical decisions: accuracy versus explainability. Hastings Center Rep. 49(1), 15–21 (2019)

Magnet, J.: Vicarious liability and the professional employee. Can. Cases Law Torts 6, 208–226 (2015)

Matthias, A.: The responsibility gap: ascribing responsibility for the actions of learning automata. Ethics Inf. Technol. 6, 175–183 (2004)

Nyholm, S.: A new control problem? Humanoid robots, artificial intelligence, and the value of control. AI Ethics (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-022-00231-y

Nyholm, S.: Artificial intelligence, humanoid robots, and old and new control problems. In: Hakli, R., Mäkelä, P., Seibt, J. (eds.) Social Robots in Social Institutions, pp. 3–12. IOS Press (2023)

Robbins, S.: A misdirected principle with a catch: explicability for AI. Minds Mach. 29(4), 495–514 (2019)

Santoni de Sio, F., Mecacci, G.: Four responsibility gaps with artificial intelligence: why they matter and how to address them. Philos. Technol. 34(4), 1057–1084 (2021)

Tigard, D.W.: There is no techno-responsibility gap. Philos. Technol. 34(3), 589–607 (2020)

Turner, J.: Robot Rules: Regulating Artificial Intelligence. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham (2019)

Acknowledgements

I thank Alex Kaiserman, Miloš Kosterec, Naomi Osorio-Kupferblum, Matteo Pascucci, Mirco Sambrotta, Jozef Sábo, and Martin Vacek for their comments on this work. I am also grateful to Carolyn Benson for proofreading.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic in cooperation with Centre for Scientific and Technical Information of the Slovak Republic. This work was supported by the Slovak Research and Development Agency under the Contract No. APVV-22-0323 (project ‘Philosophical and methodological challenges of intelligent technologies’), by VEGA 2/0125/22 ‘Responsibility and Modal Logic’, and by the University of Oxford project ‘New Horizons for Science and Religion in Central and Eastern Europe’ funded by the John Templeton Foundation (subgrant ‘Persons of Responsibility: Human, Animal, Artificial, Divine’). The opinions expressed in the publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the view of the John Templeton Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no other competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vacek, D. Two remarks on the new AI control problem. AI Ethics (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-023-00339-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-023-00339-9