Abstract

While promoting manufacturing growth is imperative to boost economic growth, potential adverse consequences on natural resources and ecology have created sustainability-related concerns and challenges. In India, with the reform processes deepening further and the business environment becoming more market-oriented over the years, the adoption of appropriate measures for sustainable manufacturing growth under such conditions would require a deeper investigation of the underlying dynamics, particularly to address the impacts of external shocks. This is especially true when external shocks alter market dynamics and, hence, input is used significantly in the manufacturing sector. Given this backdrop, the present paper examines how the major external shocks to the Indian economy during in the post-reform era have altered the resource use patterns in selected manufacturing industries. The paper uses secondary data collected from the KLEMS database of the Reserve Bank of India for the period from 1980–81 to 2019–20 and applies descriptive statistics and econometric techniques to address the research objective. It is found that energy intensity, vertical integration, capital intensity, and rate of growth of total factor productivity decreased over the decades, whereas labour productivity experienced an increasing trend in most industries. However, the trends are mixed in the case of material intensity. Further, the regression results indicate significant effects of external shocks on resource use, factor productivity, and structural changes. There are also industry-specific differences in the nature and extent of such changes. Hence, a deeper investigation of the underlying factors and impacts at a disaggregate industry level is necessary to draw more robust insights.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

While promoting manufacturing growth is imperative to strengthen agriculture-industry linkages and boost overall economic growth, potential adverse consequences on natural resources and the ecology have created sustainability-related concerns and challenges. In particular, rapid technological progress has caused two opposite effects on the manufacturing sector [1]. On the one hand, process innovations have improved production processes and enhanced resource use efficiency [2]. On the other hand, product innovations have shortened life cycles considerably in many industries [3]. In India, with the reform processes deepening further and the business environment becoming more market-oriented over the years, the adoption of appropriate measures for sustainable manufacturing growth under such conditions would require a deeper investigation of the underlying dynamics, particularly to address the impacts of external shocks and maintain the balance between process and product innovations [2, 3]. This is especially true when external shocks alter market dynamics and, hence, input is used significantly in the manufacturing sector [4].

Such changes in the manufacturing sector through external shocks are imperative as the process of economic reforms has made a marked departure with a focus on attracting foreign investments, restructuring public sector enterprises, facilitating international trade, and enhancing market competition [5, 6]. For example, the simplification of the trade policies and removal of quantitative restrictions and tariffs have led to favourable changes in the value, composition, and direction of Indian exports [7]. Further, there has been an acceleration in factor productivity growth, primarily due to technical efficiency and progress improvements [8]. In addition, macroeconomic policies have significantly helped improve productivity [9]. While all such changes are expected to promote the growth of different industries, there are challenges with respect to enhancing demand, profit margins, product quality, and technological progress vis-à-vis the global competitors [1, 10] and encountering the adverse impacts of external shocks. In particular, with economic reforms making the business environment more market-oriented and external shocks potentially affecting the market dynamics, changes in the use of inputs in manufacturing processes are very likely to occur in the upcoming years.

Besides the effects of external shocks, factors such as rising energy prices [11] can also cause major challenges to global competitiveness. This is crucial when a weak institutional structure of a developing country impedes the domestic production system [12]. On the contrary, emerging markets, changing customer choices, global competition, and emphasis on the reliability and safety of products cause additional pressures on firms [13]. The issues have been emphasized widely in recent years, with Indian firms focussing more on sustainable production processes using cleaner technologies, sustainable raw materials, adoption of renewable energy sources, and other environmental measures.Footnote 1

The paper has six sections. The next section reviews the related literature, whereas Sect. 3 presents the conceptual framework used in the study. The data sources used and the tools and techniques applied are discussed in Sect. 4. The subsequent section presents and analyses the findings. The last section makes the conclusion and policy implications by summarizing the major findings and their implications, along with the limitations of the study and the scope of further research.

2 Review of related literature

The literature review has been divided into different sub-sections to focus on the studies which have considered variables such as labour productivity, energy intensity, material intensity, capital intensity, total factor productivity and vertical integration (considered in the present study) and to understand the challenges faced by the industries. The literature review aims to identify the research gaps and emerging issues from the existing studies to proceed with the present study that can help overcome such gaps.

The performance of the Indian manufacturing industries based on the growth of the value-added, capital intensity, labour productivity and total factor productivity suggests that the productivity growth and efficiency level have not progressed in the post-reform period, as per expectations [14]. The differences in nature and fund requirements of the industries contribute to the differences in their capital structure [15]. Existing studies show that domestic firms are more export-intensive as compared to foreign firms, whereas private firms are more export-intensive than public firms [16]. Accordingly, the export intensity of firms across industries has increased considerably during the post-reform which signals improved global competitiveness of Indian manufacturing firms following economic reforms [6]. The Indian manufacturing industries have observed an increase in the capital-labour ratio due to higher employment of capital as well as displacement of workers [17]. High emission intensive industries are capital intensive whereas low emission intensive industries are labour intensive [18]. Although one advantage of the manufacturing sector is the falling capital-output ratio and labour-capital ratio, however, the falling return on capital can turn out to be a bane for the sector [18,19,20].

The increasing level of total factor productivity is related to a lower level of energy per unit. Compared to technological change, technical efficiency can affect the productivity growth of Indian manufacturing industries [21]. The growth path of total factor productivity growth can vary since it is highly sensitive to the methodology adopted for its estimation [22]. Due to the economic reforms of 1991, manufacturing industries located in most of the Indian states have experienced faster productivity growth in the post-reform period. However, manufacturing industries located in a few other Indian states, such as Puducherry, Delhi, Bihar, Goa, and Madhya Pradesh, have either faced a slowdown in productivity growth or even a productivity decline in some cases [23].

Moreover, energy efficiency can improve due to better labour productivity and capacity utilization [24]. Energy intensity in Indian manufacturing industries depends upon the transformational shift from a less efficient technology or fuel to a more efficient one and also the efficiency gains from the newer technology or fuel adopted technology [25]. Energy efficiency spillover effects from foreign to local firms have been observed during the post-reform period [14]. Results show that firm size and raw material intensity help to determine labour productivity at the firm level [13]. Vertical integration is associated with declining marginal costs and rising mark-ups at the product level. High productivity means a higher level of R&D and investment associated with the manufacturing sector [26].

Consumer goods and intermediate-producing goods firms largely determine the structure of the manufacturing industry [25]. Moreover, foreign technology has given dynamic productivity gains in the manufacturing sector [27]. There have been diverse industry-based technical changes [8]. Some states have performed better than others in terms of value-added growth. For instance, the manufacturing sector of Gujarat (due to physical infrastructure development) has been more efficient, as compared to all India averages in the post-reform period [28].

Inefficient resource use, on the one hand, can lead to resource depletion, which is considered an adverse environmental consequence, and, on the other hand, can lead to a reduction in the economic efficiency of the Indian manufacturing industries [1, 29]. These industries should also focus on high-grade resource use which can be more productive in the long run. Selection of the appropriate resources becomes crucial during the production process of the manufacturing industries. This can give greater input with lesser energy consumption.

There have been instances of automobile industries being successful due to the adoption of green logistics and green power [30]. Green manufacturing (based on green and circular economy principles) has become popular over the years [31]. However, if not properly matched with individual and aggregate perspectives, green manufacturing can result in challenges such as future legislation, public pressure, peer pressure and top management commitment [32]. India’s challenge is to achieve low carbon-emitting industrial growth. The already-taken research and development initiatives are expected to boost industrial growth, especially for the MSMEs in the coming years [33].

The existing studies have not focussed on the changes in resource use patterns and productivity due to the impact of different external shocks on the Indian manufacturing sector. They have also neglected the impact on macroeconomic and ecological indicators as a result of external shocks in the economy. In this context, this study examines how the external shocks to the Indian economy during the post-reform period have altered the trends and patterns of resource use and productivity in selected manufacturing industries. Here, the changes in resource use are examined in terms of energy and raw materials use intensity. It is hypothesized that external shocks coupled with structural changes through vertical integration and higher capital intensity would enhance factor productivity, leading to resource use efficiency with respect to both raw materials and energies in manufacturing industries. Hence, the findings of the paper are expected to provide useful insights into encountering the adverse implications of external shocks and making the manufacturing processes sustainable. The rationale behind this study is to focus on the economic changes in the Indian manufacturing sector following the fluctuations in resource use patterns and productivity due to the effect of sudden external shocks. The environmental outcomes as a result of these changes will help to undertake industry-specific policies and regulations in this regard.

3 Conceptual framework for the study

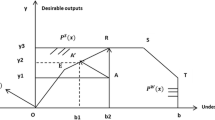

The conceptual framework of the study is based on the structure-conduct-performance paradigm of Bain (1959) and its subsequent development by [34]. This framework can potentially deal with the complex relationships amongst market structure, firms’ strategic responses, their performance, and the changes in policies and regulations. Since the present study aims to understand firms’ responses to the changing market dynamics and external shocks, the SCP framework appears appropriate for analysing the resource use patterns in firms of different industries. Figure 1 shows the interlinkages among the different variables used in the study. It is hypothesized that the need for the adoption of a sustainable and cleaner production system coupled with the changes in market dynamics and external shocks have altered the production process through resource use patterns and efficiency in the Indian manufacturing industries. Nevertheless, firms’ responses with respect to resource use and technological and production efficiency differ across industries, given that the competitive business environment and external shocks force the adoption of better and cleaner technologies and business management systems.

Here, technical progress (although results in a shorter product life cycle) is assumed to be beneficial for the firms through changes in factor productivity and resource use efficiency observed by the Indian manufacturing sector. This is crucial given that economic reforms have led to changes in policies and regulations along with facilitating the adoption of better technologies through FDI inflows and in-house R&D. Further, economic reforms and other external shocks can also potentially alter the market dynamics and other structural aspects in the long run. The conceptual framework portrayed above can potentially explore such interrelationships. Given such interrelationships, the present study uses six indicators to examine the changes following external shocks. Here, the impact on resource use is examined in terms of energy and material intensity, whereas changes in vertical integration and capital intensity are examined to understand the implications for structural aspects. Further, labour productivity and total factor productivity growth are used to examine the efficiency-related implications.

4 Data sources and methodology

The study uses secondary data collected from the KLEMS database of the Reserve Bank of India for the period from 1980–81 to 2019–20 and applies descriptive statistics and econometric techniques to address the research objective. The entire timeframe is divided into pre- (1980–81 to 1990–91) and post-reform period (1992–1993 to 2019–20) for comparative analysis. Notably, considering the abnormal situations, the years 1991–92 and 2009–10 are dropped from the dataset. Further, the post-reform period is divided into three sub-periods with breaks in 1999–2000 and 2010–11 to capture the changes following the South-East Asian crisisFootnote 2 and global economic slowdown respectively. Decadal averages are calculated to understand the trends, patterns, and fluctuations in resource use and other aspects in major industries of the Indian manufacturing sector. Eleven major industries are considered here, and all the variables are measured at constant 2011–12 prices. Table 1 shows the variables along with their measurements. Both correlation and regression analysis have been carried out to understand the degree of association and statistical significance of the changes. Notably, the years 1991–92 and 2009–10 are dropped due to adjustment issues for the base intercept in relation to economic reforms and global economic slowdown respectively.

Panel data models have been estimated separately for material intensity, energy intensity, labour productivity, total factor productivity growth, vertical integration, and capital intensity as dependent variables. More specifically, least-squares dummy variable (LSDV) models have been estimated for each of the variables to examine their industry-specific differences. In addition, the regression models include dummy variables for economic reforms, the South-East Asian crisis, and the global economic slowdown to examine their impacts. These dummy variables are included to examine the impact of these external shocks.

The following least-squares dummy variable model (LSDV) has been estimated:

Here, the dummy variable D2i = 1 for Textiles, Textile Products, Leather and Footwear industry, 0 otherwise; D3i = 1 for Wood and Products of wood industry, 0 otherwise; D4i = 1 for Pulp, Paper, Paper products, Printing and Publishing industry, 0 otherwise; D5i = 1 for Coke, Refined Petroleum Products and Nuclear fuel industry, 0 otherwise; D6i = 1 for Chemicals and Chemical Products industry, 0 otherwise; D7i = 1 for Rubber and Plastic Products industry, 0 otherwise; D8i = 1 for Basic Metals and Fabricated Metal Products industry, 0 otherwise; D9i = 1 for Machinery industry, 0 otherwise; D10i = 1 for Electrical and Optical Equipment industry, 0 otherwise; D11i = 1 for Transport Equipment industry, 0 otherwise and so on. Further, the dummy variables ER, SEAC and GFC stand for the economic reforms, South East Asian crisis and global financial crisis respectively, with ER = 1 for the period from 1992–93 to 2019–20 as 1 and 0 otherwise, SEAC = 1 for the period from 1999–00 to 2008–09 as 1 and 0 otherwise, and GFC = 1 for the period from 2010–11 to 2019–20 as 1 and 0 otherwise.

5 Results and discussions

5.1 Trends and patterns in production processes

5.1.1 Changes in energy and material intensities

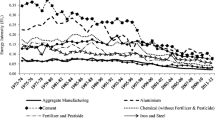

While manufacturing firms are highly dependent on high-quality and imported intermediate goods in order to enhance their productivity [35], Table 2 shows a considerable change in energy use in different industries with most of them experiencing lesser energy intensity during the post-reform period. According to [36], an increase in crude oil prices has led to a significant reduction in energy intensity in many industries. Besides, foreign-owned firms appear to be more technically efficient and, hence, less energy-intensive [37]. It is also argued that firms with higher TFPG or returns to scale output are likely to be more energy efficient [38, 39]. Although energy intensity has increased in the food and wood industry, possibly due to growing mechanization [36], the increase has not been substantial.

Table 3 shows a very high material intensity in the fuel-related industry, possibly because a wide range of by-products can be produced therein [40]. Notably, material intensity has increased in some industries depending on their nature and the type of raw materials used in such industries. In particular, the use of materials has been consistent over the years in the food, machinery, and transport equipment industries. However, some raw materials are energy intensive as well indicating their complementarity [37,38,39]. This is important given that the Indian manufacturing sector has a significant increase in the import of raw materials [41].

5.1.2 Changes in factor productivities

The TFPG influences overall economic growth, including output productivity, human capital, entrepreneurship, competitiveness, technological development, and innovations [8, 42]. Generally, TFPG depends on the age of firms (negative but significant relationship), market share (positive relationship), employees’ contribution (U-shaped relationship) and export intensity (inverted U-shaped relationship) [43]. This is contradictory to the results obtained from Table 4. Table 4 shows that TFPG remained positive throughout the period in food products, beverages and tobacco, and electrical and optical equipment. However, many of the industries recorded a deceleration in TFPG in the post-reform period.

Although the textiles had a high TFPG in the post-recession period, the overall TFPG in the industry is not very high due to the sluggish growth rate in the past two decades. A similar case is seen in the wood and wood products industry. The electrical and optical equipment industry recorded a high TFPG during 2000–01 to 2008–09, but it could not be maintained afterward. From Tables 2 and 4, it has been observed that higher TFPG may not always result in lower energy efficiency as shown in [38, 39]

Like TFPG, labour productivity has also varied across industries as well as over time (Table 5). Further, except for the wood industry, the rest of the industries have experienced an increase in labour productivity in the post-reform period, possibly due to product and process innovations [44]. In spite of the increasing dependence on updated technology in the global manufacturing sector, the Indian manufacturing sector has equally focussed on labour use due to unskilled labour. While wood is a natural, renewable as well as biodegradable raw material with legal restrictions and hence little attention given [45], chemicals and transport equipment industries had a considerably high labour productivity during 2010–11 to 2019–20. These industries have emerged as big exporters, possibly because of their improved product quality [46, 47].

5.1.3 Changes in vertical integration and capital intensities

While vertical integration is influenced by factors such as transaction costs, demand variability and market power motive [48], and information externalities due to uncertainties [49], it can potentially help the firms in better coordination and investment decisions [50]. In addition, vertical integration also serves as a strategy for proper management and customization of production according to consumer needs [48]. However, Table 6 shows that vertical integration has decreased for all the industries in the post-reform period, except for fuel and chemicals which shows that most of the manufacturing industries have neglected the process of vertical integration. This is so possibly because vertical integration reduces flexibility in industrial operations. It is also possible that decreasing externalities have reduced the extent of vertical integration in several industries. On the contrary, fuel and chemical industries have greater vertical integration, possibly due to their lower costs and higher economies of scale. Higher vertical integration indicates better productivity and higher profits.

Besides, capital intensity has also decreased in most of the industries, except food products, chemicals, and fuels during the post-reform period (Table 7). Although there are fluctuations, the post-reform period has mostly faced a declining trend due to the aftereffects of the global recession in 2008–09. Further, the capital base of an industry also depends on the size of firms. For example, large firms are likely to have higher capital intensity as compared to small and medium enterprises [51]. However, the results obtained from Table 7 do not give a clear picture of the industry-specific size of the firms. Apart from size, profitability, non-debt tax shield, growth in assets, liquidity and interest coverage also have a linear relationship with the capital structure of an industry [52].

Thus, there have been diverse natures and extent of changes in resource use, factor productivity, and structural aspects across different industries of the Indian manufacturing sector during the post-reform period [42]. While most of the industries have recorded decreasing energy and material intensities, showing a shift towards efficient resource use, lower capital share, and vertical integration may be largely because of changing business environments and opportunities. On the other hand, both labour as well as total factor productivity growth have increased over the years, possibly due to the increasing pressure of competition following the economic reforms of 1991.

The pair-wise correlation matrix presented in Table 8 shows the association between resource use (i.e., material intensity and energy intensity) and other aspects of manufacturing (i.e., vertical integration, labour productivity, total factor productivity growth, and capital intensity). It is found that the nature and extent of association varies across industries. Further, in many cases, this association is not statistically significant. Such variations in association across the variables create the necessity of examining their differences statistically, particularly with experiences of major external shocks. The next sub-section attempts for the same.

5.2 Econometric investigation of changes in production processes

Table 9 shows the summary statistics of the estimated as well as the dummy variables included in the models. The regression results are presented in Tables 10, 11 and 12. In the estimated models, the food products are taken as the base industry (for base intercept). Here, three dummy variables (for economic reforms, South-Asian crisis and global economic slowdown) are included to specify the panel data for regression models in the econometric analysis. These dummy variables examine if the respective external shocks have any significant impact. Industry-specific differential intercepts are also estimated. These differential intercepts are deviations from the base intercept. In the estimated models, the respective F-statistic confirms their overall significance, except the model on TFPG (which is significant at 14 percent level).

Table 10 shows that external shocks have affected both material and energy intensity. However, while average energy consumption in Indian industries has reduced following different shocks, material use has decreased following economic reforms only. On the contrary, material intensity is found to be higher after other shocks. External shocks affect the terms of trade of countries leading to a higher focus on domestic production rather than expensive imports. In addition, the differential intercepts of material intensity for machinery and electrical equipment industries are not significant, whereas, in the case of energy intensity, it is not significant for textile and petroleum industries. Importantly, the sign of the differential intercepts differs across industries. This indicates that there are industry-specific differences in average energy or material intensity vis-à-vis food products.

Here, the number of observations is less for TFPG as compared to labour productivity because the first observation is used for the computation of the growth rate (Table 11). However, while average labour productivity has been higher following economic reforms and the global economic slowdown, external shocks have no significant impact on TFPG. Further, the differential intercepts of labour productivity are significant for petroleum products, chemicals, machinery, and transport equipment, whereas, in the case of TFPG, it is so for wood and petroleum products. However, while the differential intercepts are negative for TFPG, they are positive in the case of labour productivity.

Table 12 shows the significant impact of external shocks on vertical integration and capital intensity of the manufacturing sector. While the impacts of all the shocks are found to be negative on vertical integration, it is positive for economic reforms in the case of capital intensity (though negative for other shocks). Thus, both vertical integration and capital intensity have decreased following the global economic slowdown and the Southeast Asian crisis. However, while vertical integration has been higher during the post-reform period, it is found to be reversed in the case of capital intensity. Importantly, all the differential intercepts are significant and positive, except for petroleum products. In the case of petroleum products, the differential intercept is significant but negative.

Table 13 summarizes the regression results. It is evident that while average energy consumption has decreased and there has been greater vertical disintegration following the external shocks, the impacts vary in the case of other indicators. For example, material use intensity is found to be lower following economic reforms, but higher after other shocks. However, the impact is found to be reversed in the case of capital intensity. Further, none of the shocks has any significant impact on total factor productivity growth. Importantly, statistical significance and signs of the industry-specific intercepts vary. This indicates that industry-specific resource use, factor productivity and structural aspects differ vis-à-vis food products.

6 Conclusion and policy implications

The paper finds that there has been a significant impact of external shocks on resource use in Indian industries. It is evident that while average energy consumption has decreased and there has been greater vertical disintegration following the external shocks, the impacts vary in the case of other indicators. For example, material use intensity is found to be lower following economic reforms, but higher after other shocks. However, the impact is found to be reversed in the case of capital intensity. Further, none of the shocks significantly impact total factor productivity growth. Importantly, statistical significance and signs of the industry-specific intercepts vary. This indicates that industry-specific resource use, factor productivity and structural aspects differ vis-à-vis food products.

Apart from the food products, chemicals and fuel industries, there has been a decrease in the capital intensity in the post-reform period. On the other hand, the food industry has portrayed a decline in TFPG as compared to other industries in the post-reform period. Moreover, most of these industries have shown a decrease in energy intensity over the years. Although, there has been a slight increase in energy intensity in exceptional cases, however, it is negligible as compared to the pre-reform period. Material intensity has decreased for some industries whereas it has increased for some others depending upon whether the raw materials are domestically produced or imported. Vertical integration has been reduced for most of the industries because of its expensive nature. The results also show that, except for the wood industry, every other industry has shown a significant rise in labour productivity due to product and process innovations. The material intensity and energy intensity have a positive relationship between them in the case of most of the Indian manufacturing industries. There has been a high impact of the structural breaks on both material as well as energy intensities.

It is evident that, except for TFPG, all the indicators show the significant impact of external shocks. Further, the nature and significance of the indicators also differ across the industries. The results obtained from the present study highlight the linkage of different macroeconomic factors with the existing literature. However, it has shown contradictory results in some cases. TFPG does not always follow an inverted U-shape and gives a positive relationship with energy efficiency [38, 39, 43]. Capital intensity may not only depend on firm size [51]. Such differences may be because of the nature of the industries, market dynamics, firms’ business strategies, and industry-specific policies and regulations. Therefore, further analysis of these aspects is necessary for more robust policies and regulations.

The present study has not highlighted the shock-specific impact on resource use patterns and productivity in the Indian manufacturing sector. The reasons behind the trends and patterns of different macroeconomic variables affecting the manufacturing industries have been neglected. Further scope of the study includes policies and regulations that can prioritize individual factors such as labour, capital, land and entrepreneurship rather than total factor productivity of the Indian manufacturing industries. The policies should also focus on the environmental outcomes as a result of changes in different industry-specific macroeconomic variables.

Data availability

The paper uses secondary data collected from the KLEMS database of the Reserve Bank of India for the period from 1980–81 to 2019–20 which is publicly available. The dataset will be shared on request.

Notes

Nevertheless, concerns remain for small and medium enterprises that lack resource use efficiency, innovations, and productivity growth.

Although the South East Asian crisis started in Thailand in 1997–98 and spread to other countries subsequently, here the break is introduced in the year 1999–2000 to capture its aftermath affect as well as the implications of formation of a more stable government in India.

References

Uddin MMM. What are the dynamic links between agriculture and manufacturing growth and environmental degradation? Evidence from different panel income countries. Environ Sustain Indic. 2020;7:100041.

Rochina-Barrachina ME, Mañez JA, Sanchis-Llopis JA. Process innovations and firm productivity growth. Small Bus Econ. 2010;34:147–66.

Srinivasan S, Pauwels K, Silva-Risso J, Hanssens DM. Product innovations, advertising, and stock returns. J Mark. 2009;73(1):24–43.

Patnaik A. Measuring demand and supply shocks from COVID-19: an industry-level analysis for India. Margin J Appl Econ Res. 2022;16(1):76–105.

Kanda R. Indian manufacturing sector: a review on the problems & declining scenario of Indian industries. Int J Sci Res. 2015;4:1039–42.

Basant R, Mishra P. Trends in strategies and performance of the Indian corporate sector: What has changed in two decades of economic reforms? Ahmedabad: Indian Institute of Management; 2016.

Sahni P. Trends in India’s exports: a comparative study of pre and post reform period. IOSR J Econ Finance. 2014;3(2):8–18.

Ray SC. Did India’s economic reforms improve efficiency and productivity? A nonparametric analysis of the initial evidence from manufacturing. Indian Econ Rev. 2002;37:23–57.

Ghosh S. Do economic reforms matter for manufacturing productivity? Evidence from the Indian experience. Econ Model. 2013;31:723–33.

Mukherjee S. Challenges to Indian micro small scale and medium enterprises in the era of globalization. J Glob Entrep Res. 2018;8:1–19.

Sadath AC, Acharya RH. Effects of energy price rise on investment: firm level evidence from Indian manufacturing sector. Energy Econ. 2015;49:516–22.

Mani S. The role of industrial policy in market-friendly economies case of COVID-19 vaccine R&D and its manufacturing in India and its contrast with the US-II. Econ Polit Wkly. 2022;57:51–8.

Deshmukh J, Pyne PK. Labour productivity and export performance: firm-level evidence from Indian manufacturing industries since 1991. 2013.

Golder B. Energy intensity of Indian manufacturing firms: effect of energy prices, technology and firm characteristics. Sci Technol Soc. 2011;16(3):351–72.

Manjule R. Impact of capital structure in Indian industries. Int J Sci Eng Res. 2014;5(1):2239–49.

Rentala S, Anand B, Shaban M. Technological capabilities and firm resources as determinants of export competitiveness: evidence from Indian pharmaceutical industry using quantile regression approach. J Med Mark. 2014;14(2–3):133–44.

Das P, Sengupta A. Wages, productivity and employment in Indian manufacturing industries: 1998–2010. J Ind Stat. 2015;4(2):208–20.

Ranjan R. Determinants of emission and energy intensities in indian organized manufacturing sector. Artha Vijnana J Gokhale Inst Polit Econ. 2015. https://doi.org/10.21648/arthavij/2015/v57/i3/109158.

Krishna KL, Goldar B, Erumban AA, Das PC, Aggarwal SC. Sources of India’s post-reform economic growth: an analysis based on India KLEMS database. Econ Pol Wkly. 2022;57(31):36–43.

Basole A, Narayan A. Long-run performance of the organised manufacturing sector in India: an analysis of sub-periods and industry-level trends. Econ Pol Wkly. 2020;55(10):35–44.

Joshi RN, Singh SP. Estimation of total factor productivity in the Indian garment industry. J Fash Mark Manag Int J. 2010;14(1):145–60.

Pradhan G, Barik K. Fluctuating total factor productivity in India: evidence from selected polluting industries. Econ Polit Wkly. 1998;33:M25–30.

Deb AK, Ray SC. Economic reforms and total factor productivity growth of Indian manufacturing: An inter-state analysis (No. 2013–04). University of Connecticut, Department of Economics. 2013.

Haider S, Bhat JA. Does total factor productivity affect the energy efficiency: evidence from the Indian paper industry. Int J Energy Sect Manage. 2020;14(1):108–25.

Dasgupta S, Roy J. Analysing energy intensity trends and decoupling of growth from energy use in Indian manufacturing industries during 1973–1974 to 2011–2012. Energ Effi. 2017;10(4):925–43.

Stiebale J, Vencappa D. Import competition and vertical integration: evidence from India. J Dev Econ. 2022;155:102790.

Rijesh R. Technology import and manufacturing productivity in India: firm level analysis. J Ind Compet Trade. 2015;15(4):411–34.

Unni J, Lalitha N, Rani U. Economic reforms and productivity trends in Indian manufacturing. Econ Polit Wkly. 2001;36:3914–22.

Zhang W, Ma W, Ji Y, Fan M, Oenema O, Zhang F. Efficiency, economics, and environmental implications of phosphorus resource use and the fertilizer industry in China. Nutr Cycl Agroecosyst. 2008;80:131–44.

Karurkar S, Unnikrishnan S, Panda SS. Study of environmental sustainability and green manufacturing practices in the Indian automobile industry. OIDA Int J Sustain Dev. 2018;11(06):49–62.

Toke LK, Kalpande SD. Critical success factors of green manufacturing for achieving sustainability in Indian context. Int J Sustain Eng. 2019;12(6):415–22.

Mittal VK, Sangwan KS. Prioritizing drivers for green manufacturing: environmental, social and economic perspectives. Procedia Cirp. 2014;15:135–40.

Pulicherla KK, Adapa V, Ghosh M, Ingle P. Current efforts on sustainable green growth in the manufacturing sector to complement “make in India” for making “self-reliant India.” Environ Res. 2022;206:112263.

Tirole J. The theory of industrial organization. Cambridge: MIT press; 1988.

Sharma C. Imported intermediate inputs, R&D, and productivity at firm level: evidence from Indian manufacturing industries. Int Trade J. 2014;28(3):246–63.

Reddy BS, Ray BK. Understanding industrial energy use: physical energy intensity changes in Indian manufacturing sector. Energy Policy. 2011;39(11):7234–43.

Sahu S, Narayanan K. Determinants of energy intensity in Indian manufacturing industries: a firm level analysis. 2010; 4(21646)

Sahu SK, Sharma H. Productivity, energy intensity and output: a unit level analysis of the Indian manufacturing sector. J Quant Econ. 2016;14(2):283–300.

Bala Subrahmanya MH. Energy intensity and economic performance in small scale bricks and foundry clusters in India: does energy intensity matter? Energy Policy. 2006;34(4):489–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2004.06.016.

Solomon S. Sugarcane by-products based industries in India. Sugar Tech. 2011;13:408–16.

York R, Ergas C, Rosa EA, Dietz T. It’s a material world: trends in material extraction in China, India, Indonesia, and Japan. Nat Cult. 2011. https://doi.org/10.3167/nc.2011.060201.

Das N, Bera P. Estimation of TFPG from the cost-function for the Indian manufacturing industries: a panel-time series approach. 2021; 11: 175–192

Maiti S, Chakraborty C. Total factor productivity growth of indian fabrics sector: a firm level analysis. 2018; Vol. XXII, 2017-18, ISSN - 0975-8003

Woltjer G, Van Galen M, Logatcheva K. Industrial innovation, labour productivity, sales and employment. Int J Econ Bus. 2021;28(1):89–113.

Mai C, Kües U, Militz H. Biotechnology in the wood industry. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;63:477–94.

Kathuria V, Aiyar A. Link between exporting and productivity: firm level analysis for Indian chemical industry. Sci Technol Soc. 2011;16(3):309–31.

Keshari PK, Saggar M. A firm level study of the determinants of export performance in machinery and transport equipment industry of India. 2013; Vol. 36, No. 3 (1989): pp. 36–48.

Bhuyan S. An empirical evaluation of factors determining vertical integration in US food manufacturing industries. Agribus Int J. 2005;21(3):429–45.

Hennessy DA. Information asymmetry as a reason for food industry vertical integration. Am J Agr Econ. 1996;78(4):1034–43.

Liu X. Vertical integration and innovation. Int J Ind Organ. 2016;47:88–120.

Das S, Roy M. Inter-industry differences in capital structure: evidence from India. Finance India. 2007;21(2):517.

Adhegaonkar V, Indi RM. Determinants of capital structure: a case of Indian chemical industry. Int J Mark Technol. 2012;2(10):130–6.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TM: idea and contextualisation, introduction and literature review, data collection, analysis, results and discussions. BB: idea and contextualisation, objective, conceptual framework, data collection, analysis, results and discussions, limitations and policy recommendations. Both the authors significantly contributed in finalizing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Yes.

Informed consent

Yes.

Competing interests

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mishra, T., Behera, B. External shocks and dynamics of resource use patterns: empirical evidence from the Indian manufacturing sector. Discov Sustain 5, 159 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00362-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00362-8