Abstract

This research explores economic growth dynamics in five ASEAN countries (1980–2020), analyzing the short and long-term impact of financial development (FD), oil prices, investment (INV), and inflation on GDP growth. Panel ARDL analysis reveals a transient positive link between FD and long-term GDP growth, necessitating a holistic approach for short-term stability. Similarly, oil prices exhibit long-term volatility, urging diversification strategies. In contrast, consistent and significant relationships exist between INV and GDP growth in both time frames, underscoring investment's pivotal role. The study emphasizes managing inflation for sustained growth, offering vital insights for policymakers, economists, and analysts in fostering ASEAN's economic stability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Economic growth holds utmost significance for the advancement of a nation's economy, as it generates well-paying jobs and improves the overall quality of life. Furthermore, when managed effectively, economic growth contributes to the retention and expansion of employment opportunities and investments within a community. Financial development stands as a crucial prerequisite in the economic planning process, fostering sustainable economic growth and overall development [1, 2]. The evolution of the financial sector plays a pivotal role in driving economic progress. Consequently, it becomes imperative for Asian nations to stay attuned to innovations and changes within their respective domains, all while strengthening their economic performance. The trajectory of financial development primarily centers on output-related factors, alongside the constructive influence of capital and accumulation in attaining long-term economic advancement. The effects of oil prices on macroeconomics have perennially captivated economists' attention.

The frequency of growth in gross domestic product (GDP) is a measure of how effectively the economy is expanding. This rate should be compared between the most recent quarter's overall economic performance and the output of the previous quarter. GDP quantifies the total economic output of a country. The progression of financial development results in increased savings and investment mobilization. However, initiatives for financial development involve the formulation and execution of various strategies, the creation of relevant financial products, and the establishment of an environment conducive to efficient operations of financial institutions. Developing countries encounter inefficiencies and numerous obstacles in the process and provision of financial services, hindering their efficiency. They grapple with the challenge of efficiently mobilizing financial services [3]. Economists have closely studied the relationship between reliance on natural resources, particularly oil, and economic growth [4]. Furthermore, theoretically, oil and other non-renewable natural resources should yield significant economic advantages.

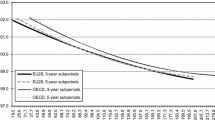

According to World Bank data, Malaysia's GDP experienced a decrease from 7.4 percent to 5.9 percent between 1980 and 1982. Consequently, economic growth declined from 3.3 percent to 0.9 percent. Following this trend, Malaysia's GDP demonstrated an upward trajectory by banks from 1986 to 1996, ranging from 1.2 percent to 10 percent. However, during the Asian financial crisis in 1997, GDP growth rate plummeted to −7.4 percent in 1998. In 2010, Malaysia achieved the highest GDP growth of about 7.3 percent, followed by Singapore at around 14.5 percent. Notably, Malaysia's GDP witnessed a decline starting in 2010, reaching a significant low of −5.6 percent in 2020. Over the past four decades, the indicator of oil dependence has fluctuated due to global commodity price shifts. Initially at 16 percent in the late 1970s, the index dropped until the mid-1990s. However, since 1995, the index ascended to 18 percent in 2008, just before the global financial crisis, which led to lower oil prices and subsequently decreased reliance on natural resources [5]. Table 1 shows the average real GDP growth (%) of five selected countries.

Between 1965 and 1997, Indonesia's economy maintained an annual growth rate of nearly seven percent. This achievement pushed Indonesia from the category of 'low-income countries' to 'low and middle-income countries.' The late 1990s saw the outbreak of the Asian Economic Crisis, significantly impacting Indonesia's economy. Data revealed that Indonesia's GDP experienced its most substantial improvement in 1980, reaching about 9.9 percent, and then gradually decreased to around 9 percent in 1990. Subsequently, during 1991–2000, the GDP witnessed a decline from 8.9 percent to 5 percent, hitting its lowest point of −13.1 percent in 1998. From 2001 to 2010, Indonesia's GDP reached its lowest point in 2001 at approximately 3.6 percent and peaked at 7.4 percent in 2008. Between 2011 and 2020, World Bank data illustrated a decline from 6.2 percent to a significant low of −2.1 percent, exacerbated by the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the case of the Philippines, the economy experienced a substantial recession in 2020 due to the direct impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to a year-on-year GDP decline of 9.6 percent. Data indicated that from 1980 to 1990, the GDP growth rate decreased from 5.1 percent to 3 percent. In the subsequent decade, 1991–2000, the lowest GDP was recorded in 1991 at around −0.4 percent, followed by an increase to 4.4 percent in 2000. From 2010 to 2017, the Philippines registered an average annual GDP growth rate of 6.9 percent, a notable improvement from the 4.4 percent growth rate during 2000–2009 and a considerable increase compared to the average growth in the 1980s and 1990s. The year 2017 witnessed total investment contributing to nearly 40 percent of GDP growth, with fixed investment reaching 25 percent of GDP—the highest share in over three decades. However, from 2018 to 2020, GDP experienced a significant decline of −9.6 percent due to the pandemic's impact.

For Singapore, the highest GDP growth during the 1980–1990 period was observed in 1988 at 11.3 percent, while the lowest occurred in 1985 at around −0.6 percent. From 1991 to 2000, the lowest GDP was recorded in 1998 at approximately −2.2 percent, while the highest was achieved in 2010 at 14.5 percent. In 2020, Singapore's real GDP growth rate stood at −5.4 percent. Over the past two decades, Singapore's real GDP growth has exhibited volatility, declining from 2001 to 2020, culminating in a -5.4 percent contraction in 2020. Singapore, being a small open economy, is naturally susceptible to fluctuations in global oil prices. Notably, oil price shocks have not been linked to recessions in Singapore, despite substantial increases in inflation rates. Financial development in Singapore has steadily progressed over the years, reaching 132.6782 in 2020.

In the case of Thailand, the sub-period of 1980–1996 marked a period of robust economic growth, predominantly driven by advancements in the manufacturing sector. This phase was characterized by stability, with a low coefficient of variation in growth rates. In contrast, the years 1997–2000 represented a challenging period in Thailand's economic history, with the lowest GDP recorded at -7.6 percent in 1998. Subsequent to this, during 2001–2010, the highest GDP growth rate of 7.5 percent was achieved in 2010. In 2020, Thailand's real GDP growth rate was -6.1 percent. Thailand's real GDP growth has displayed volatility in recent years, with a declining trend from 2001 to 2020, resulting in a -6.1 percent contraction in 2020 due to the pandemic's impact.

Over the last three decades, the ASEAN region has seen fluctuations in GDP from one year to another. These unpredictable changes, influenced by financial development and oil prices, bring up several questions. Firstly, how does financial development and oil price affect economic growth? Secondly, how does high oil price impact a country's economic growth? Many studies have explored the relationship among financial development, oil prices, inflation rates, and investment in economic growth. Researchers like [6,7,8] have looked into how economic growth relates to factors such as financial development, oil prices, investment, and inflation. Therefore, this study conducts empirical analyses to examine the influence of financial development, oil prices, investment, and inflation on the economic growth of five selected ASEAN countries.

The main objective of this study is to explore economic growth dynamics in five ASEAN countries from the year1980–2020, after collecting the data from World Development Indicator (WDI), the short and long-term impact of financial development (FD), oil prices, investment (INV), and inflation on GDP growth will be analyzed using panel ARDL technique through the STATA software.

The contribution of this study lies in its ability to inform policy-making and strategic planning efforts aimed at advancing economic growth and stability in ASEAN countries. By examining the impacts of financial development, oil prices, investment, and inflation on GDP growth over a 40-year period, the research will provide policymakers with valuable insights into the factors driving economic expansion. This knowledge can help policymakers formulate targeted policies to promote sustainable economic development, such as strategies to enhance financial infrastructure, diversify energy sources to mitigate the impact of oil price fluctuations, and manage inflation to sustain growth. Additionally, the study's findings can guide investors and businesses in making informed decisions by identifying key drivers of economic growth in the region.

This article comprises five sections. It begins with the introduction, followed by a literature review. The third section outlines the research methods employed. Subsequently, the results and discussions are presented, leading to the fifth section encompassing the conclusions and policy implications.

2 Literature review

Economic growth refers to the expansion of a country's economy, and this can be measured in different ways, with Gross Domestic Product (GDP) being the most common method [9]. According to [10], GDP represents the overall output of an economy and can be categorized into three parts: the total value of produced output, the total income earned during production, and the total spending on the output. Business investment is also a crucial factor in GDP as it boosts productive capacity and job creation [11]. When consumer spending and business investment drop significantly, especially after a recession, government spending becomes crucial for GDP. The decline in the ranking of ASEAN countries was evident in their GDP performances during 2010–2011 [12]. Consequently, Indonesia's GDP dropped from 6.4 percent to 6.2 percent, Malaysia's from 7.5 percent to 5.3 percent, the Philippines from 7.3 percent to 3.9 percent, Singapore's from 14.5 percent to 6.3 percent, and Thailand's contracted from 7.5 percent to 0.8 percent, the worst since the Asian crisis. Enhancing economic growth helps countries raise their per capita income [13].

According to [14] financial development (FD) is mainly connected to how production works and the positive impact of having money to invest and save for long-term growth. In literature, financial development is seen as the most important thing for making an economy grow [15,16,17]. Especially in developing countries, policymakers want to know if they should make the financial parts of the economy more open [18]. Based on what we know from economic theories and real-life examples, when a place has good financial development, it helps the economy grow. In a previous study by [19], they looked at how financial development, money, and government spending affect how much money a country makes. They used a type of math called econometrics, which helps us understand how things are connected over time. They found that when financial development gets better, it usually means the economy grows. But the money that the government spends, and other financial things don't always make a big difference in how much a country makes.

Many studies using information from different countries and years have shown that when financial development gets better, the economy usually grows more too [20,21,22]. According to [23] studied 35 countries' data from 1860 to 1963 and saw a good connection between financial development and how much money each person makes (GDP per capita). [24] looked at different countries and found that when the financial part of the economy is strong (like banks’ lending money to people and businesses), the economy usually grows faster. Many different researchers have studied why oil prices change in the past [25,26,27]. Also, how much a country depends on oil can affect how financial development and economic growth are connected. On one side, oil prices can be thought of as adding to the money that financial institutions have, making the connection between financial growth and economic growth stronger. Economists say that sudden changes in oil prices can increase how much it costs to make things, which leads to higher prices for everything (inflation) [28].

According to [29], the cost of oil can be influenced by many things like how countries manage their economies, the overall global economy, legal issues in places that use a lot of oil, and how stable countries that sell oil are. Sometimes, throughout history, wars and problems between countries have made oil prices go up. Another topic this study is connected to is how natural resources, like oil, affect the financial world and how banks grow. A lot of studies, like the ones by [30] and [31], have looked at how oil prices change and how it affects the stock market. Some studies, starting with [32] and [33], say that when oil prices go up, the stock market goes down.

Inflation is the topic that experts still talk about because it can create problems once it starts happening. According to [34] too much inflation can cause political pressure to reduce it. But financial authorities might not want to reduce it, which makes people unsure about how much prices will go up in the future. This uncertainty can make economic decisions slower and slow down how much the economy grows. Different ideas in economics lead to different conclusions about how economic growth changes because of inflation. According to [35], when they looked at 170 countries between 1960 and 1992, they found that inflation rates above 10–20% per year usually hurt economic growth. Valogo et al. [36] studied the relationship between inflation and growth in Malaysia from 1970 to 2005. They found that when inflation is above 3.89%, it hurts growth, but when it's below that, there's a positive link between inflation and growth.

According to [37] gross fixed capital formation means adding more capital assets for future use. We are using it as a way to measure how much a country invests, shown as a part of the total production of the country (GDP). This is about getting more things like buildings and machines that will help the country make more things in the future. This also happens when people save money, which then leads to more investments. When there is more investment, the country gets more projects going, which makes the economy grow [38, 39].

Therefore, based on the literature review and the above discussion the following hypothesis is developed for the current study.

Hypothesis 1: There is a significant relationship between financial development (FD)and economic growth (GDP) of selected ASEAN countries.

Hypothesis 2: There is a significant relationship between oil prices and economic growth (GDP) of selected ASEAN countries.

Hypothesis 3: There is a significant relationship between investment and economic growth (GDP) of selected ASEAN countries.

Hypothesis 4: There is a significant relationship between inflation and economic growth (GDP) of selected ASEAN countries.

3 Methodology

This study uses panel data to estimate the financial development, oil price, investment, and inflation on economic growth, of selected ASEAN countries Malaysia, Indonesian, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand.

where GDP indicates the economic growth of the country, macroeconomic indicators consist of financial development (FD), oil price (OIL), investment (INV) and inflation (INF). The main reason to use panel data is as it measures the impact in a group and not in individual units which means that very little information is lost by taking the panel perspective [40]. Moreover, panel data reduces the noise coming from the individual time series therefore, heteroscedasticity is not an issue in panel data analysis [41]. Furthermore, panel data is best suited where data availability is an issue, particularly for developing countries where short-period variables are available [42]. Panel estimation techniques take this heterogeneity into account by allowing for subject-specific variables as well as dynamic changes due to repeated cross-sectional observations. This study is strictly on heterogeneous panel data modeling, also known as panel-ARDL. The Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) model is a widely recognized and robust econometric approach capable of capturing both short-term and long-term dynamics in the relationships under examination [43]. By utilizing the ARDL model, this study aims to unravel the intricate connections between the variables of interest and discern the impact of the independent variable on the dependent variables over time [44]. The adoption of this rigorous econometric methodology ensures the validity and reliability of the findings, providing valuable empirical evidence to inform economic policy decisions, investment strategies, and academic discourse in the field of finance and economics [45].

The generalized ARDL (p, q, q, …, q) model is specified as:

where Yit is the dependent variable, (X’it)’ is a (k X 1) vector that is allowed to be pure I (0) or I (1) or cointegrated, \(\updelta\) I id the coefficient of the lagged dependent variables called scalars; βij are K × 1 coefficient vector; φi is the unit-specific fixed effect; I, …, N; t = 1, 2, 3, …, T; p, q are optimal lag orders; εit is the error term. The study used Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), the Schwarz Bayesian Criterion (SBC) or Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and the Hannan-Quinn Criterion (HQ) for the selection of lag. The re-parameterized ARDL (p, q, q, q, …, q) error correction model is specified as

where θi is the – (1-δi) shows the group-specific speed of adjustment coefficient (expected that θi < 0), λ’I is the vector of long-run relationships, ECT is [Yit-1- λ’X i,t] is the error correction term represents the long run information in the model, term and \(\upxi\) it and β′ij are the short-run dynamic coefficients. Based on the above model, y is GDP growth dependent variable including both the lag and difference value for short-run and long-estimation. While x shows the set of independent variables with their lags and difference value.

This study focuses on the impact of financial development, oil prices, investment, and inflation on economic growth. The data pertaining to financial development, oil price, investment, inflation, and economic growth across the five ASEAN countries was collected from the World Development Indicators (WDI) website from 1980 to 2020.

3.1 Description of variables

The dependent variable in this study is Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth rate which is a measure of the economic performance of a country [24]. It represents the percentage change in the value of goods and services produced by an economy over a specific period, usually measured on a quarterly or annual basis. A positive GDP growth rate indicates economic expansion, while a negative growth rate suggests economic contraction. Governments, policymakers, and economists closely monitor GDP growth rates to assess the overall health and performance of an economy. Financial development (FD) is mostly connected to how things are made, especially the good impact of having money and saving it for the economy to grow better [24]. Financial development helps the economy get bigger and work better. Many studies have looked at how financial development affects how the economy grows. Most of these studies have looked at rich countries where the financial system works well. Oil has always had a special role in the world economy. We see from many research papers, there is a lot of study about oil prices. Some of these studies looked at what things make oil prices change. Others checked how oil prices affect different things. The study of [46] shows that when oil prices change, it usually helps the economy grow in the short term but makes it smaller in the long term. Second, when the changes in oil prices aren't the same, when they go up, the economy usually shrinks in the long run but grows a bit in the short term. Arouri and Rault [47] found that in countries that sell a lot of oil, when oil prices change, it affects how much money people make in the stock market. Inflation, which is often measured by things like the Consumer Price Index (CPI) means that the money’s value goes down over time [48]. This makes people spend their savings more because things are getting more expensive, and their money doesn't buy as much. The effects of inflation on the economy can be good or bad. The main goal of big economic plans is to help the economy grow a lot but keep inflation low and steady. Investment has a big impact on how fast the economy grows [49, 50]. When investment grows fast, the economy gets bigger, which makes more investment happen.

4 Result and discussion

4.1 Pre-estimation results

For empirical analysis, the study uses the panel ARDL dynamic method to investigate the impacts of financial development, oil prices, investment, and inflation on the economic growth, of selected ASEAN countries. Furthermore, statistical assessments with a theoretical and conceptual discussion of the results are adopted to answer the research hypothesis. In addition to the empirical outcomes, the study incorporated the descriptive statistics of the variables used in the study as well as a diagnostic test for best-fit models.

Table 2 shows the descriptive analysis of the provided economic variables reveals a dynamic economic landscape. The annual GDP growth rate demonstrates an average expansion of 5.08%, with a moderate standard deviation of 4.06%, reflecting a degree of variability in economic performance. Financial development in the domestic private sector exhibits positive trends, with an average growth rate of 4.09% and a low standard deviation of 0.67%, indicating a relatively stable financial environment. Oil prices, with an average of 2.31, show significant fluctuations, as evidenced by a substantial standard deviation of 2.76%. Investment, measured by gross fixed capital formation, experiences an average growth rate of 3.28% with low variability (0.23%). Inflation remains relatively low, averaging 1.13%, but with a moderate standard deviation of 1.10%, indicating some variability in general price levels.

Table 3 presents the correlation analysis among the economic variables reveals valuable insights into their interrelationships. Financial development (FD) exhibits a strong negative correlation with oil prices (OIL), indicating that as domestic private sector financial activities increase, oil prices tend to decrease. Additionally, there is a moderate positive correlation between FD and investment (INV), suggesting that higher financial development aligns with increased investment in gross fixed capital formation. Furthermore, FD displays a strong negative correlation with inflation (INF), implying that enhanced financial development is associated with lower inflation rates. Oil prices (OIL) and inflation (INF) show a moderate positive correlation, indicating that as oil prices rise, inflation tends to increase. The correlation between investment (INV) and inflation (INF) is very weak, suggesting a limited linear relationship between these two variables. Overall, the correlation analysis unveils intricate connections between the economic variables, offering valuable insights for understanding potential patterns and dynamics within the observed data.

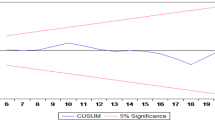

Table 4 displays the outcomes of the unit root test for the level and first differences via trend and intercept. The unit roots' performance is conducted through the utilization of the Im-Pesaran-Shin (IPS) unit root test. This examination holds significant importance in the context of our study as it aids in discerning the stationary properties of the variables under investigation. The result of unit root shows that GDP, FD and INV are stationary at first difference, however, OIL and INF are stationary at level, so the result of the unit root test gives the level of confidence for the application of panel ARDL for estimation [51,52,53,54]. After the unit root test, the selection of optimal lag is based on the most common lag selection for each variable and is used to represent the lags for the model such as (1,0,0,0) to avoid the problem of degree of freedom. After the selection of optimal lag, Padroni’s cointegration test is applied to find the long run cointegration among the variables [55, 56]. Cointegration is ascertained from the statistical significance of the long-run coefficients and the error correction term.

In the analysis presented in Table 5, the significance of cointegration testing becomes evident. Through the examination of two distinct sets of cointegration results, the study examines the existence of enduring relationships among the variables employed in the estimation process. Notably, the null hypothesis of no-cointegration is decisively dismissed at the 1% significance level for both panel and group statistics.

4.2 Post-estimation results

Before proceeding with the estimation, a crucial step is taken by employing the Hausman test criteria. This test holds significance as it aids in choosing between the Pooled Mean Group (PMG) and Mean Group (MG) estimation methods. The selection is based on the probability value derived from the test. When the p-value of the Hausman test exceeds the 5% level of significance, it signals that the PMG estimation method is more suitable for the estimation process. This decision carries importance because it ensures the adoption of an appropriate estimation technique that aligns with the underlying data characteristics. By consistently applying these criteria to all panels of datasets from the selected ASEAN countries, the research establishes a methodological foundation that enhances the validity and reliability of the subsequent analysis.

Table 6 shows that in the selected ASEAN countries, the financial development (FD) is positively significant with GDP in the long-run, and further it suggests that the coefficient for FD is 8.130074, with a standard error of 2.290196. The z-value is 3.55, and the p-value is 0.000, indicating that the coefficient is highly significant at the 1% level. This suggests that a one-unit increase in FD is associated with an 8.130074 unit increase in the GDP in the long run. However, this relationship is insignificant in the short run with the coefficient for FD is −7.708967 and a standard error of 6.190066. The z-value is −1.25, and the p-value is 0.213. This indicates that the coefficient is not statistically significant. The result is similar to the study of [46]. In other words, as financial development increases, there is a corresponding positive impact on GDP in the long term. Furthermore, it suggests that over a short period, the influence of financial development on GDP is not reliable or significantly different from zero.

Similarly, the coefficient of ECT is significant indicating that the impact of an adjustment also exists with the GDP growth policy of the country, and it signifies that the coefficient associated with the Error Correction Term (ECT) is statistically significant. This indicates that there is an adjustment mechanism at 50%, and changes in the variable under examination are associated with changes in the GDP growth policy of the country. The presence of a significant ECT implies that any deviations from the short-run equilibrium between these variables will be corrected over time, suggesting a dynamic and interdependent relationship between the variables.

The results described in the context of a positive long-term relationship between financial development (FD) and GDP, which becomes insignificant in the short run, along with the presence of a significant Error Correction Term (ECT), are often associated with the concept of "convergence" or "adjustment towards equilibrium" in the context of economic growth theories. In economic literature, the convergence hypothesis suggests that over time, less developed economies tend to grow faster than more developed ones, leading to a narrowing of the income gap between them. The long-term positive relationship between financial development and GDP growth aligns with the idea that increased financial development can stimulate economic activity in the long run. However, the diminishing significance in the short run may be indicative of the convergence process, where economies adjust and move towards a short-run equilibrium. The ECT suggests that any deviations from the short-run equilibrium are corrected over time, indicating a dynamic adjustment process. This dynamic and interdependent relationship is often associated with the adjustment mechanism in models like the Solow Growth Model or other models that incorporate short-run equilibrium concepts.

The findings from Table 7 reveal a noteworthy pattern in the relationship between oil prices and GDP growth in the examined context. In the long term, there exists a statistically significant association between oil prices and GDP growth, indicating that immediate fluctuations in oil prices play a discernible role in influencing the region's economic output. The coefficient for OIL is −1.113301 with a standard error of 0.50305. The z-value is −2.21, and the p-value is 0.027. This indicates that the coefficient is statistically significant at the 5% level. The negative sign of the coefficient suggests that an increase in OIL is associated with a decrease in the GDP in the long run. However, in the short term, this relationship loses its statistical significance, suggesting that the impact of oil prices on GDP growth diminishes over the short run with the coefficient for OIL is 2.968991 with a standard error of 2.183684. The z-value is 1.36, and the p-value is 0.174. This indicates that the coefficient is not statistically significant. The result is parallel with the study of [57]. This shift may imply a certain level of short-term volatility, with the economy being responsive to immediate changes in the oil market, while in the long run, other factors or mechanisms may come into play, leading to a less predictable or consistent influence of oil prices on overall economic growth.

The significance of the Error Correction Term (ECT) coefficient in the analysis signifies the presence of an adjustment mechanism, indicating that any deviations from the long-run equilibrium between the variables are systematically corrected over time. Specifically, the statistically significant ECT coefficient, noted at 64%, implies that approximately 64% of any short-term deviations from equilibrium are adjusted in each period. This adjustment mechanism is associated with changes in the GDP growth policy of the country, suggesting a dynamic and interdependent relationship between the variables under examination. The finding implies that the studied variables are not static; instead, they exhibit a dynamic relationship where the system tends to move back towards a stable, long-term equilibrium, emphasizing the importance of considering both short-term fluctuations and long-term equilibrium in the analysis.

The results presented in Table 7, showcasing a significant long-term relationship between oil prices and GDP growth that diminishes in significance over the short run, along with the identification of an Error Correction Term (ECT) and associated adjustment mechanism, align with economic theories pertaining to long-term volatility and short-term equilibrium adjustments. The significant immediate impact of oil prices on GDP growth reflects theories emphasizing the influence of long-term external shocks, such as fluctuations in oil prices, on economic output. However, the diminishing significance in the short run suggests a nuanced pattern, hinting at the role of short-term equilibrium adjustment mechanisms. This finding resonates with economic theories that stress the importance of adjustments over time to maintain stability. Additionally, the parallel results with a study by [57] suggest consistency in these dynamics across different analyses, reinforcing the idea that the observed long-term influence and short-term insignificance may be inherent to broader economic processes. In essence, these findings underscore the complexity of the relationship between oil prices and GDP growth, emphasizing the need to consider both long-term fluctuations and short-term equilibrium dynamics in economic analyses.

Table 8 shows that investment (INV) has a significant relationship with GPD growth of the selected ASEAN countries in the long run. The coefficient for INV is 3.821633 with a standard error of 1.220678. The z-value is 3.13, and the p-value is 0.002. This indicates that the coefficient is statistically significant at the 1% level. The positive sign of the coefficient suggests that an increase in investment (INV) is associated with an increase in GDP in the long run. Furthermore, the relationship is also significant in the short term with the coefficient for INV is 16.73008 and a standard error of 5.334533. The z-value is 3.14, and the p-value is 0.002. This indicates that the coefficient is statistically significant at the 1% level. The positive sign of the coefficient suggests that an increase in the first difference of investment is associated with an increase in GDP in the short run. This finding is supported by the study of [58]. This means that changes in investment levels are associated with corresponding changes in GDP growth rates over both shorter and longer time periods. In practical terms, a positive relationship suggests that an increase in investment is linked to an increase in GDP growth, and a decrease in investment is associated with a decrease in GDP growth. Conversely, a negative relationship would imply the opposite—increased investment corresponds to a decrease in GDP growth, and decreased investment corresponds to an increase in GDP growth. This finding can have important implications for policymakers and analysts, indicating that investment plays a significant role in driving economic growth in the selected ASEAN countries. It may suggest that policies or conditions encouraging investment, such as favorable investment climates or targeted incentives, could positively impact overall economic growth in both the short and long term.

The significance of the Error Correction Term (ECT) coefficient in the analysis indicates the presence of an adjustment mechanism, highlighting how any short-term deviations from the long-run equilibrium between the variables are systematically corrected over time. Specifically, the statistically significant ECT coefficient, noted at 90%, suggests that approximately 90% of any short-term deviations from equilibrium are adjusted in each period. This finding implies a dynamic process within the relationship being examined, wherein the system actively responds to disturbances by gradually restoring balance. In practical terms, the adjustment mechanism underscores the interdependence of the variables and their tendency to move back towards a stable, long-term equilibrium. The 90% coefficient provides insight into the speed at which this adjustment occurs, offering valuable information for understanding the dynamics of the relationship and the system's capacity to self-correct in response to short-term disruptions.

The results presented, demonstrating a significant relationship between investment (INV) and GDP growth in both the short and long term, along with the presence of a significant Error Correction Term (ECT) coefficient, align with economic theories related to investment-led growth and adjustment mechanisms toward equilibrium. The positive association between investment and GDP growth supports theories emphasizing the role of capital accumulation in fostering economic expansion. This finding echoes the study of [58], reinforcing the notion that changes in investment levels are linked to corresponding changes in GDP growth rates over different time horizons. The significance of the ECT coefficient further suggests the existence of an adjustment mechanism, indicating that any short-term deviations from the long-run equilibrium between investment and GDP growth are systematically corrected over time. This dynamic process underscores the interdependence of the variables and their tendency to move back toward a stable, long-term equilibrium. In essence, these results align with investment-driven growth theories, which posit that policies fostering investment, such as favorable investment climates or targeted incentives, could positively influence overall economic growth in both the short and long term.

The result from Table 9 indicates that there is a statistically significant relationship between inflation and GDP growth in both the long run. The coefficient for INF is 2.400739 with a standard error of 0.5251213. The z-value is 4.57, and the p-value is 0.000. This indicates that the coefficient is statistically significant at the 1% level. The positive sign of the coefficient suggests that an increase in inflation is associated with an increase in GDP in the long run. Furthermore, it also suggests that this relationship is significant in the short run with the coefficient for INF is -1.848759 and a standard error of 0.6695988. The z-value is -2.76, and the p-value is 0.006. This indicates that the coefficient is statistically significant at the 1% level. The negative sign of the coefficient suggests that an increase in the first difference of inflation is associated with a decrease in GDP in the short run. The result supports the study of [59], however it opposes the findings of [56]. This means that changes in the inflation rate are associated with corresponding changes in GDP growth rates over both shorter and longer time periods. In practical terms, a positive relationship might suggest that an increase in inflation is linked to an increase in GDP growth, and a decrease in inflation is associated with a decrease in GDP growth. Conversely, a negative relationship would imply the opposite—increased inflation corresponds to a decrease in GDP growth, and decreased inflation corresponds to an increase in GDP growth. The significance of this relationship can have important implications for policymakers and analysts. It suggests that inflation, which is a measure of the rate at which general prices for goods and services rise, is not only an economic indicator but also influences the overall economic growth of the studied context. Policymakers may need to consider this relationship when formulating monetary and fiscal policies to achieve desired levels of economic growth while managing inflationary pressures.

The result suggests that the Error Correction Term (ECT) coefficient is statistically significant, indicating the presence of an adjustment mechanism in the analyzed relationship between inflation and GDP growth. The Error Correction Term is often used to capture the speed at which a system corrects deviations from its long-run equilibrium. In this context, the statistically significant ECT coefficient of 71% implies that approximately 71% of any short-term deviations from equilibrium between inflation and GDP growth are adjusted in each period. In practical terms, this finding implies a dynamic process within the relationship being examined. If there is a disturbance or deviation from the long-run equilibrium between inflation and GDP growth, the system actively corrects itself by approximately 71% each period, leading to a gradual return to the long-term balance. This adjustment mechanism is a key aspect of many economic models that consider how economies respond to shocks and deviations, and it indicates a dynamic and interdependent relationship between the variables being analyzed.

The results presented, indicating a statistically significant relationship between inflation and GDP growth in both the short run and the long run, align with economic theories related to the Phillips curve and the monetary policy transmission mechanism. The Phillips curve suggests an inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment in the short run, and the idea that inflation may be linked to changes in GDP growth over different time horizons is consistent with this framework. The result supporting the study of [59] further reinforces the idea that inflation dynamics play a role in shaping economic growth. However, the opposition to the findings of [60] highlights the complexity and context-specific nature of the inflation-GDP growth relationship. In practical terms, the result suggests that policymakers and analysts should consider the impact of inflation on overall economic growth when formulating monetary and fiscal policies. The presence of a statistically significant Error Correction Term (ECT) coefficient at 71% implies the existence of an adjustment mechanism, indicating that short-term deviations from the equilibrium between inflation and GDP growth are systematically corrected over time. This aligns with theories of economic adjustment and equilibrium-seeking mechanisms in response to shocks, further emphasizing the dynamic and interdependent nature of the relationship between inflation and GDP growth.

5 Conclusions and policy implications

The objective of this study was to explore economic growth dynamics in five ASEAN countries from the year1980-2020, after collecting the data from World Development Indicator (WDI), the short and long-term impact of financial development (FD), oil prices, investment (INV), and inflation on GDP growth analyzed using panel ARDL technique through the STATA software. The results from the analysis of selected ASEAN countries reveal distinctive patterns in the relationships between various economic factors and GDP growth. In the case of financial development (FD), a positive and statistically significant relationship with GDP in the long run suggests that increased financial development contributes to economic output in the long term. However, this impact is not sustained over the short term, indicating a lack of short-term reliability or statistical significance. A similar trend is observed in the relationship between oil prices and GDP growth, where a significant association in the long term diminishes over the short term. This implies long-term volatility, with the economy reacting to long run changes in the oil market, while other factors or mechanisms may come into play in the short run, leading to a less predictable influence of oil prices on economic growth. On the other hand, the analysis indicates a significant and consistent relationship between investment (INV) and GDP growth in both the short and long term. Finally, regarding inflation, the study supports a statistically significant relationship with GDP growth in both time frames, contradicting some prior findings. This implies that changes in inflation rates are linked to corresponding changes in GDP growth rates, underscoring the importance of considering inflationary pressures in the formulation of effective monetary and fiscal policies to achieve desired economic growth levels. In the realm of financial development (FD), while acknowledging the short-term positive impact on GDP, policymakers should adopt a comprehensive approach that goes beyond financial development alone for long-term economic stability. Given the short-term volatility observed in the relationship between oil prices and GDP growth, policymakers should remain vigilant to immediate changes in the oil market. However, for sustained economic planning, diversification strategies, investments in alternative energy, and the development of resilient economic policies are recommended to mitigate the potentially unpredictable influence of oil price fluctuations over time. Finally, recognizing the significant relationship between inflation and GDP growth in both short and long terms, policymakers should carefully manage inflationary pressures through effective monetary and fiscal policies that balance inflation control with the promotion of economic growth. A comprehensive and balanced approach to these considerations will be crucial for long-term economic sustainability in the ASEAN region. Policy implications stemming from the analysis of selected ASEAN countries suggest a multifaceted approach to economic management. While acknowledging the short-term positive impact of financial development (FD) on GDP, policymakers should prioritize long-term stability by diversifying economic strategies beyond FD alone. Proactive measures are essential to mitigate short-term volatility in oil prices, including diversification strategies, investments in alternative energy, and resilient economic policies. Creating an attractive investment climate is crucial, leveraging the consistent and significant relationship between investment (INV) and GDP growth. Additionally, effective monetary and fiscal policies are needed to balance inflation control with economic growth promotion, given the significant relationship between inflation and GDP growth in both short and long terms.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Demetriades PO, Hussein KA. Does financial development cause economic growth? Time-series evidence from 16 countries. J Dev Econ. 1996;51(2):387–411.

Ibrahim H, Bala MD. Air stable pincer (CNC) N-heterocyclic carbene–cobalt complexes and their application as catalysts for C-N coupling reactions. J Organomet Chem. 2015;1(794):301–10.

Boularedj S, Faouzi T. Measuring the impact of the financial development on the economic growth in Algeria. Eur Sci J. 2015;11(16):413–26.

Badeeb RA, Lean HH, Clark J. The evolution of the natural resource curse thesis: a critical literature survey. Resour Policy. 2017;1(51):123–34.

The World Bank. World Development Indicators Databank. 2023. Worldbank.org. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators

Hussin F, Saidin N. Economic growth in ASEAN-4 countries: a panel data analysis. Int J Econ Financ. 2012;4(9):119–29.

Estrada GB, Park D, Ramayandi A. Financial development and economic growth in developing Asia. Asian Development Bank Economics Working Paper. 2010 Nov(233).

Malarvizhi CA, Zeynali Y, Mamun AA, Ahmad GB. Financial development and economic growth in ASEAN-5 countries. Glob Bus Rev. 2019;20(1):57–71.

Mattioli G, Roberts C, Steinberger JK, Brown A. The political economy of car dependence: a systems of provision approach. Energy Res Soc Sci. 2020;1(66):101486.

Vaubel R. The political economy of the International Monetary Fund: a public choice analysis. In: Vaubel R, Willett TD, editors. The political economy of international organizations. Oxfordshire: Routledge; 2019. p. 204–44.

Udemba EN. A sustainable study of economic growth and development amidst ecological footprint: new insight from Nigerian Perspective. Sci Total Environ. 2020;25(732):139270.

Nguyen TV, Pham LT. Scientific output and its relationship to knowledge economy: an analysis of ASEAN countries. Scientometrics. 2011;89(1):107–17.

Friedman BM. The moral consequences of economic growth. In: Berger PL, Imber JB, editors. Markets, morals, and religion. Oxfordshire: Routledge; 2017. p. 29–42.

Qamruzzaman M, Jianguo W. Nexus between financial innovation and economic growth in South Asia: evidence from ARDL and nonlinear ARDL approaches. Financial innovation. 2018;4(1):1–9.

Adeleye BN, Bengana I, Boukhelkhal A, Shafiq MM, Abdulkareem HK. Does human capital tilt the population-economic growth dynamics? Evidence from Middle East and North African countries. Soc Indic Res. 2022;162(2):863–83.

Alom K. Financial development and economic growth dynamics in South Asian region. J Dev Areas. 2018;52(4):47–66.

Khan I, Hou F, Irfan M, Zakari A, Le HP. Does energy trilemma a driver of economic growth? The roles of energy use, population growth, and financial development. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2021;1(146):111157.

Bamiatzi V, Bozos K, Cavusgil ST, Hult GT. Revisiting the firm, industry, and country effects on profitability under recessionary and expansion periods: a multilevel analysis. Strateg Manag J. 2016;37(7):1448–71.

Hasan R, Barua S. Financial development and economic growth: evidence from a panel study on South Asian countries. Asian Econ Financial Rev. 2015;5(10):1159–73.

Jin Y, Gao X, Wang M. The financing efficiency of listed energy conservation and environmental protection firms: evidence and implications for green finance in China. Energy Policy. 2021;1(153):112254.

Cao X, Kannaiah D, Ye L, Khan J, Shabbir MS, Bilal K, Tabash MI. Does sustainable environmental agenda matter in the era of globalization? The relationship among financial development, energy consumption, and sustainable environmental-economic growth. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2022;29(21):30808–18.

Hung NT. Green investment, financial development, digitalization and economic sustainability in Vietnam: evidence from a quantile-on-quantile regression and wavelet coherence. Technol Forecast Soc Chang. 2023;1(186):122185.

Hacievliyagil N, Eksi IH. A micro based study on bank credit and economic growth: manufacturing sub-sectors analysis. South East Eur J Econ Bus. 2019;14(1):72–91.

The BW, Economies F-G. The finance-growth nexus in high and middle income economies. J Smart Econ Growth. 2020;5(2):45–58.

Jawadi F. Understanding oil price dynamics and their effects over recent decades: an interview with James Hamilton. Energy J. 2019;40:1–4.

Ederington LH, Fernando CS, Lee TK, Linn SC, May AD. Factors influencing oil prices: A survey of the current state of knowledge in the context of the 2007–08 oil price volatility. Working Paper. 2011 Aug 30.

Haugom E, Mydland Ø, Pichler A. Long term oil prices. Energy Econ. 2016;1(58):84–94.

Gong X, Xu J. Geopolitical risk and dynamic connectedness between commodity markets. Energy Econ. 2022;1(110):106028.

Mousavi A, Clark J. The effects of natural resources on human capital accumulation: a literature survey. J Econ Surv. 2021;35(4):1073–117.

Salahuddin M, Alam K, Ozturk I, Sohag K. The effects of electricity consumption, economic growth, financial development and foreign direct investment on CO2 emissions in Kuwait. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2018;1(81):2002–10.

Nanda S, Berruti F. Municipal solid waste management and landfilling technologies: a review. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;19(2):1433–56.

Degiannakis S, Filis G, Arora V. Oil prices and stock markets: a review of the theory and empirical evidence. Energy J. 2018;39(5):85–130.

Prabheesh KP, Padhan R, Garg B. COVID-19 and the oil price–stock market nexus: evidence from net oil-importing countries. Energy Res Lett. 2020. https://doi.org/10.46557/001c.13745.

Acheampong AO, Dzator J, Dzator M, Salim R. Unveiling the effect of transport infrastructure and technological innovation on economic growth, energy consumption and CO2 emissions. Technol Forecast Soc Chang. 2022;1(182):121843.

Thanh SD. Threshold effects of inflation on growth in the ASEAN-5 countries: a panel smooth transition regression approach. J Econ Finance Adm Sci. 2015;20(38):41–8.

Valogo MK, Duodu E, Yusif H, Baidoo ST. Effect of exchange rate on inflation in the inflation targeting framework: is the threshold level relevant? Res Glob. 2023;1(6):100119.

Rakshit B, Bardhan S. Does bank competition promote economic growth? Empirical evidence from selected South Asian countries. South Asian J Bus Stud. 2019;8(2):201–23.

Ahmad Z, Hidthiir MH, Rahman MM. Impact of CSR disclosure on profitability and firm performance of Malaysian halal food companies. Discov Sustain. 2024;5(1):18.

Butters D, Gann C. Towards professionalism in higher education: an exploratory case study of struggles and needs of online adjunct professors. Online Learn. 2022;26(3):259–73.

Baltagi BH, Baltagi BH. Econometric analysis of panel data. Chichester: Wiley; 2008.

Ahn SC, Lee YH, Schmidt P. Panel data models with multiple time-varying individual effects. J Econ. 2013;174(1):1–4.

Khelfaoui I, Xie Y, Hafeez M, Ahmed D, Degha HE, Meskher H. Information communication technology and infant mortality in low-income countries: empirical study using panel data models. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(12):7338.

Nkoro E, Uko AK. Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) cointegration technique: application and interpretation. J Stat Econ Methods. 2016;5(4):63–91.

Bentzen J, Engsted T. A revival of the autoregressive distributed lag model in estimating energy demand relationships. Energy. 2001;26(1):45–55.

McNown R, Sam CY, Goh SK. Bootstrapping the autoregressive distributed lag test for cointegration. Appl Econ. 2018;50(13):1509–21.

Tang W, Wu L, Zhang Z. Oil price shocks and their short-and long-term effects on the Chinese economy. Energy Econ. 2010;1(32):S3-14.

Arouri ME, Rault C. Oil prices and stock markets in GCC countries: empirical evidence from panel analysis. Int J Financ Econ. 2012;17(3):242–53.

Duca JV, Muellbauer J, Murphy A. What drives house price cycles? International experience and policy issues. J Econ Lit. 2021;59(3):773–864.

Carkovic M, Levine R. Does foreign direct investment accelerate economic growth. Does Foreign Direct Invest Promot Dev. 2005;15(195):220.

Pedroni P. Critical values for cointegration tests in heterogeneous panels with multiple regressors. Oxford Bull Econ Stat. 1999;61(S1):653–70.

Phillips PC. Estimation and inference with near unit roots. Economet Theor. 2023;39(2):221–63.

Çelik O, Adali Z, Bari B. Does ecological footprint in ECCAS and ECOWAS converge? Empirical evidence from a panel unit root test with sharp and smooth breaks. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2023;30(6):16253–65.

Im KS, Pesaran MH, Shin Y. Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. J Econ. 2003;115(1):53–74.

Yamarik S, El-Shagi M, Yamashiro G. Does inequality lead to credit growth? Testing the Rajan hypothesis using state-level data. Econ Lett. 2016;1(148):63–7.

Pedroni P. Panel cointegration: asymptotic and finite sample properties of pooled time series tests with an application to the PPP hypothesis. Economet Theor. 2004;20(3):597–625.

Phyoe EE. The relationship between foreign direct investment and economic growth of selected ASEAN countries. Int J Bus Adm Stud. 2015;1(4):132.

Tang S, Selvanathan EA, Selvanathan S. Foreign direct investment, domestic investment and economic growth in China: a time series analysis. World Econ. 2008;31(10):1292–309.

Lim YC, Sek SK. An examination on the determinants of inflation. J Econ Bus Manag. 2015;3(7):678–82.

Faria JR, Carneiro FG. Does high inflation affect growth in the long and short run? J Appl Econ. 2001;4(1):89–105.

Izuchukwu OO. Analysis of the contribution of agricultural sector on the Nigerian economic development. World Rev Bus Res. 2011;1(1):191–200.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A. The first author supervised the manuscript’s conceptualization and provided oversight. B. Second author wrote the main manuscript text and analyzed the data and collected the data. C. Third author assisted with data collection, research framework development. D. Fourth author assisted in developing research framework and performed proofreading the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hidthiir, M.H.b., Ahmad, Z., Junoh, M.Z.M. et al. Dynamics of economic growth in ASEAN-5 countries: a panel ARDL approach. Discov Sustain 5, 145 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00351-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00351-x