Abstract

The urgency to restore landscapes to counteract deforestation, soil degradation, and biodiversity loss has resulted in a global commitment to landscape restoration. Many frameworks and tools have emerged for the design and implementation of restoration activities. The frameworks tend to focus on selected dimensions of sustainability, with the majority focusing on the ecological. Current frameworks miss a balanced assessment of (planned) interventions taking into account also the social dimension relating to participation and ownership as well as improvement of livelihoods. The objective of this review is to assess current frameworks for identification of strength and weaknesses and to derive an integrated Forest Landscape Restoration (FLR) assessment framework model that shall help overcome current limitations. Applying systematic literature review, a total of 22 frameworks are selected and analyzed in-depth applying qualitative content analysis. Our review finds that frameworks vary with respect to their focus and restoration objectives. They also differ in relation to spatial and temporal scale, degree of stakeholder participation, consideration of ecological and social dimensions, monitoring and evaluation approaches, as well as provisions for exit strategies. Findings are summarized in form of an integrated FLR assessment framework, comprising six interlinked components: stakeholder participation, customization, time and scale of application, social-ecological balance, monitoring, evaluation and learning, and exit strategy. The proposed framework facilitates design and implementation of context specific interventions, balancing the nexus of social and ecological dimensions of FLR and acknowledges the need to also include reflection on learnings and planning of an exit strategy for long-term success.

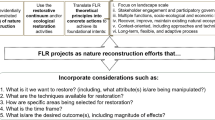

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

Current FLR frameworks emphasize on ecological restoration, neglecting its social dimension, especially socio-cultural context and social cohesion.

-

Understanding restoration as a social-ecological transformation process and putting more emphasis on a balanced approach is key to facilitate long-term success of restoration initiatives.

-

Review results are summarized in form of an integrated FLR assessment framework that comprises six interlinked components: stakeholder participation, customization, time and scale of application, social-ecological balance, monitoring, evaluation and learning, and exit strategy.

-

The framework advocates for context specific planning to ensure restoration that best fits the respective environment.

-

Monitoring and evaluation must be an integral part of each FLR project that is undertaken, in conjunction with multiple stakeholders and over longer time. Specific indicators of FLR targets must be defined for the monitoring of implementation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Although the global discourse on Forest Landscape Restoration (FLR) goes back to the 1980s, it only became a global movement in the 2010s [1, 2]. In 2000, WWF collaborated with IUCN to define FLR for the first time as “a planned process that aims to regain ecological integrity and enhance human wellbeing in deforested or degraded landscapes”. The intention is to ensure the forest quality is improved in the landscape for the benefit of both people and biodiversity rather than converting the entire landscape to forest [3,4,5]. Following this, there was a global commitment to intensify forest restoration, including the Bonn Challenge, which aimed to restore 150 million hectares by 2020 and later increased to 350 million hectares during the New York Declaration on Forests [6]. In parallel, as part of this global commitment, 34 African countries pledged to restore 100 million hectares of land by 2030, thus contributing to the commencement of the African Forest Landscape Restoration Initiative (AFR 100). The AFR 100 initiative is a country-led initiative to restore degraded landscapes across Africa contributing to the African Union Agenda 2063 and the Bonn Challenge [7].

As a global commitment, FLR is believed to provide a solution to the world’s deforestation and degradation problems, climate change mitigation and adaptation, future agricultural productivity and food security for supporting poor rural communities, as well as for water and soil conservation [8, 9]. Mansourian, Vallauri [10] define FLR as a planned process that aims to regain ecological integrity and enhance human well-being in deforested or degraded landscapes. FLR is the long-term process of regaining ecological functionality and enhancing human well-being across deforested and degraded forest landscapes [11], representing a new approach to forest restoration [12]. FLR prioritizes biodiversity conservation and human livelihoods. Moreover, the implementation of FLR should be highly supported by policies whereby actors implementing FLR should not face the complexity of navigating through policy elements and frameworks [13].

Despite official recognition that ecological and social dimensions must be addressed through FLR, we argue that in practice there is a tendency to focus more on the ecological dimension. There is a tendency to equate well-being with (socio) economic improvements. This narrow understanding of the social dimension in restoration results in a common neglect of socio-cultural context and social cohesion on local and local to national scales [14]. Also, there is still a lack of understanding of how social aspects of restoration projects and contexts influence the social and ecological outcomes of FLR projects [15]. Few integrate stakeholders in the early definition and planning phase of FLR. However, the duration of stakeholders’ involvement in the process of FLR can highly determine its success [16, 17].

Further, community perspectives need to become an integral element of FLR implementation and concepts advanced on how to achieve this best [14, 18] Socio-cultural context on the ground, such as governance system, power structure, and social values, plays an important role in successful land use interventions to enhance ecological functionality and human wellbeing [18]. Insufficient attention to social aspects in restoration activities results in a greater risk of social injustice for the most vulnerable people. Multiple social dimensions must be considered in the restoration activities in order to achieve effective and equitable outcomes [14]. Implementation challenges relate to selecting appropriate FLR options that fit to local contexts and meet the interests of multiple stakeholders, governance limitations, and the lack of clarity on how to measure FLR success [19, 20]. It is imperative to strengthen the social dimension of restoration and also to focus more on interlinked social-ecological consequences of restoration because these are intimately intertwined, especially in the Global South [5, 21, 22].

Not addressing the social dimension can undermine potentially positive effects of planned interventions [23, 24]. Social risks, including poverty and structural inequities can limit community commitment to ecosystem restoration, thereby indirectly causing the overexploitation of restored sites. Governance of resources is another key aspect impacting the social dimension. While bottom-up initiatives of FLR exist, numerous conservation efforts in the Global South are governed in a top-down fashion, including with respect to restoration initiatives such as government-led mobilization of FLR [6, 25, 26]. Inappropriate governance, however, can have negative social consequences, for example by undermining community cohesion [27, 28]. Similarly, conflicting expectations of restoration projects can slow down or inhibit the implementation of restoration activities [6, 21] or can reinforce social inequalities [29] if the diversity of stakeholders is not represented in the design and implementation of restoration activities or if stakeholders cannot agree on common goals. Thus, there is a need to more fully consider social conditions and limitations in landscape restoration.

To better plan and monitor FLR efforts at local, national, and global levels, different restoration framework tools have been developed [1]. These methodologies, frameworks, and guidelines all aim to facilitate the restoration process. Restoration toolboxes may be equipped with a variety of techniques and tools that can be used to achieve more than one objective [30]. Even though much has been studied on the applicability of FLR frameworks to achieve ecological regaining and other objectives related to environmental objectives [6, 31], few studies examine how to reduce the gap of interlinkages between social and ecological goals [32]. The objective of this review is to assess current frameworks for identifying strengths and weaknesses and summarize results in an integrated FLR assessment framework. The integrated FLR assessment framework shall help to overcome current limitations in FLR assessment and implementation. The framework shall help policymakers and practitioners to better plan and implement more sustainable restoration practices that target social-ecological restoration.

2 Methods

2.1 Data source and type

To identify existing FLR frameworks, a systematic literature review was conducted. Systematic reviews are used to meticulously summarize all available literature concerning the research topic in question and are often utilized to provide a comprehensive overview of a specific discipline. A systematic review encompasses using a systematic method to search and summarize evidence on the research question(s) with a detailed and comprehensive plan of the study (inclusion and exclusion criteria for the papers). A limitation of systematic literature reviews lies in the potential for publication bias, compounded by the reliance on predefined key terms for search criteria, language, and the bounding of publication years, which may restrict the comprehensiveness and diversity of studies included. We mitigated bias in our systematic literature review by employing predefined key terms document analysis and involving a team of international researchers simultaneously in the review process with continuous exchange on terms and findings to ensure same understanding of concepts, inclusion of literatures and analysis criteria. Furthermore, we bounded the year of publication by 2000, the introduction of the term FLR [33]. Furthermore, through expert consultation during the review process representativeness of literature selection was verified and missing sources from primary web search complemented by grey literature recommended by the experts. The selected method of systematic reviews minimizes study biases, thereby making the study findings more reliable [34, 35].

The review was conducted in April 2022, across several web-based platforms (Scopus, Google Scholar, and Web of Science) that cover the vast majority of English peer-reviewed scientific articles. Focus on English literature was chosen as FLR is a global commitment with many key players using English as one of their working languages. Thus, most frameworks are available in English. However, there are frameworks also available in other or multiple languages, such as English and French as in the case of the A guideline for FLR in the tropics. The focus on English was taken by the authors’ team, composed of international researchers from English and French speaking countries, with many having worked on restoration for decades. The search terms used for this review included “forest,” “restoration,” landscape,” “guide,” “framework,” and “method.” These terms were derived from an exploratory evaluation of studies on FLR [36], which provides a stock of FLR issues, and Chazdon and Guarigueta [37], which provides comprehensive decision support tools for FLR initiatives globally. The search terms were combined with Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) to perform the search.

In the first instance, search criteria and combinations were the same for each of the platforms. The term “Forest Landscape Restoration” was consistently included throughout the search process, while the terms “guide”, “method”, and “framework” were either included or omitted. In each search instance, at least one of these three terms had to be present. This approach was crucial in ensuring the relevance of the retrieved results to our study. There was need to restrict search criteria to title only when possible because, as in the case of Google Scholar the inclusion of title and abstract resulted in a very high number of (irrelevant) hits for the search on “forest landscape restoration” AND “method” as most abstracts include reference to a method.

The initial literature search resulted in 418 documents. To verify the literature review and to ensure that no study was missed, the ‘Connected Papers’ [38] tool was also used. ‘Connected paper’ is a tool that provides a list of papers that are related to a given paper, thereby helping to identify potential documents that are related and relevant to the study but might have been missed by the initial search using the search terms. The utilization of ‘Connected Papers’ returned findings primarily consisting of published works already included in the initial search. Results screening was commenced by removing duplicates from the initial search results which reduced the number of hits to 371 publications. This was accomplished using the duplicate function within Microsoft Excel. To ensure the relevance of identified references, the results were then first screened based on the title by ensuring the occurrence of at least one of the search terms; this resulted in 69 documents. This was then followed by a second layer of screening using the abstracts of the selected papers. The abstracts were screened to confirm that retained papers included at least one of the following: FLR implementation strategy, framework, guide, or method for implementation of FLR projects. Publications that did not focus on FLR implementation, guidance, methods, and framework were excluded. Following title and abstract based screening, a total of 31 publications were selected for in-depth review. Figure 1 illustrates the process followed to screen eligible documents for in-depth analysis.

Following an approach suggested by César, Belei [39], grey literature was also reviewed to ensure that studies from non-academic sources that might be relevant to the study were included. This was done by identifying key international organizations and initiatives working on FLR (like the World Resource Institute and the International Union for Conservation of Nature) to include frameworks and practical guidebooks produced by these institutions. This was done through a non-systematic web-based search using the same search terms as that of the scientific literature. This approach resulted in four grey literature items being added to the list for full text review resulting in a total of 35 publications for further review. During this process of in-depth analysis, 13 publications were further removed as they turned out to be short communication and commentary papers, thus out of scope. Ultimately, a total of 22 publications on FLR assessment frameworks provide the basis for this study (see Fig. 6 in the results section for the final list of frameworks analyzed).

2.2 Data analysis

The frameworks were analyzed and information systematized in a two-step approach. First, all 35 frameworks identified through systematic literature review were analyzed following a pre-defined matrix table (Excel). These codes were defined by the authors’ team prior to the analysis in accordance with the review objective and following the understanding of restoration as a social and ecological process that requires high stakeholder participation as well as a balanced approach from local to global scale to allow for a sustainable win–win situation on the social and ecological side of restoration. Codes of analysis were thus: objectives, scale and time of application, stakeholder involvement, components, and limitations of the frameworks. Applying these codes, one researcher investigated all 35 frameworks, while an additional screening was carried out in parallel by five other researchers to mitigate reviewer bias. These researchers divided the references among themselves and conducted screening based on the pre-established terms and contexts, comprehensive reading was done to screen the framework documents that are meet the criteria of eligibility (FLR guidelines, frameworks, and methods) for further in-depth analysis. Results were then shared and discussed among the authors and results on the reviewed frameworks summarized in one overall matrix. The matrix table summarizes the overall content, type of the framework, its objective, level of application and if tested in any geographical scale and its key features. It was at the end of this step, 13 frameworks were dismissed and 22 were selected for further in-depth analysis.

For the in-depth, qualitative content analysis [40,41,42] was then applied using MAXQDA version 22 software. The content analysis using MAXQDA was conducted following a combined approach of inductive and deductive code development [43]. Codes derived from the existing literature and applied in the first analysis were expanded by additional codes and sub-codes (procedures, features, limitations, and restoration options) derived through the first level analysis (see Fig. 2 for the codes applied during this step of content analysis). Framework content was subsequently examined following both manifest and latent approaches. Manifest approaches looks for visible codes in the review document whereby latent approaches explores uncovering deeper meaning implied in the text [44]. This analysis was performed by two independent researchers working in parallel. During the coding activity, regular exchange between the researchers took place to discuss and also compare findings for validation. The process of second stage review process using MAXQDA to systematize results in SWOT analysis is visualized in Fig. 2. The figure shows the content we reviewed to assess the frameworks if the key terms are introduced in the reviewed documents. In the initial phase of thorough analysis, we crafted key terms by delineating the focal points and condensing the essence of the framework’s content. We examined various aspects including the framework’s objectives, relevant stakeholders, applicability in terms of scale and timeframe, outlined procedures, suggested restoration options, distinctive features, and limitations.

The selected 22 frameworks were then analyzed and results systematized following SWOT methodology for further in-depth assessment of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT). This step was taken to reduce the level of subjectivity of the previous step where characteristics of reviewed frameworks and their general limitations found by the individual reviewers were noted. SWOT analysis as a very structured approach continues to be one of the most widely cited strategy tools that can be applied in different context approaches [45]. The identification and summary of the SWOT is based on the key summaries from the MAXQDA qualitative analysis and framework content on fulfilling the six basic principle to implement FLR [46]. These principles are: (i) focus at landscape level; (ii) stakeholder participation; (iii) restoration of multiple functions for multiple benefits; (iv) maintaining natural ecosystem within the landscape; (v) tailor to the local context using variety of approaches; and (vi) manage adaptively for long term resilience.

3 Results

3.1 General observations on FLR frameworks and their area of focus

Based on our analysis, most common thematic focus of the frameworks were identified and grouped the different frameworks in eight thematic focus areas: (i) implementation of FLR; (ii) FLR site selection; (iii) conceptualization of FLR; (iv) policy inputs; (v) biodiversity protection; (vi) ecological recovery; (vii) economic gains; and (viii) socio-cultural values. Overall, we find that 62% of the frameworks intend to identify FLR implementation sites and 67% seek to provide a common guide or process with broad implementation outlook. However, only 5% of the reviewed frameworks explicitly consider the conceptualization phase within the scope of their FLR implementation (Fig. 3). With regards to the key objectives of the frameworks, we find that focus very much differs, with some being far more narrowly focused on regaining ecological functionality than others. Our results found that ecological regaining received the most priority in drafting objectives of FLR frameworks followed by enhancing biodiversity and economic benefits. For example, the Scaling up re-greening framework restricts implementation strategy to the locals’ already-existing tree maintenance and replanting practices and exclusively incorporates local farmers. In contrast, socio-cultural values receives least priority under the reviewed frameworks. Figure 3 shows the coverage of different objectives by the reviewed frameworks.

Figure 4 visualizes the analysis of all 22 frameworks with their thematic focus areas. Our analysis shows that all but two frameworks (Forest Restoration in Landscapes Beyond Tree Planting, Improving Restoration Success) focus on several thematic areas. Hereby, the majority of frameworks focus on areas relating to regaining ecological functionality by concentrating on ecological, economic, and biodiversity issues but few on enhancing human well-being or the conceptualization of FLR. Twelve frameworks intend to provide inputs to FLR related policies. A guide to FLR in the tropics framework has a more balanced focus with the identified themes as compared to the others. ROAM framework has a balanced focus on the implementation sites and input to FLR policies. Cost benefit framework for the landscape gives a good coverage for economic benefits, ecological regaining and biodiversity. From the reviewed frameworks, only the 4 Returns Framework and the A guideline for FLR in the tropics explicitly addresses the objectives as ensuring a balance of social, economic, and environmental benefits arising from the implementation of FLR projects. Five of the frameworks consider social-cultural values in their thematic focus, namely the A guideline for FLR in the tropics, the 4 Returns for the landscape restoration, Setting local priorities and Tree diversity frameworks.

3.2 Level of application: spatial and temporal scale

Impact assessment can be conducted prior to implementation (ex-ante) identifying probable results of an intervention in advance to support the planning process as well as after implementation (ex-post) determining to what extent the intervention achieved its objectives and desired results. Also impact assessment can be conducted on different scales from local to global impacting on the assessment scope and indicators. It is always challenging to measure localized factors, improved livelihood of the local community, compared to macro aspects of restoration. Reconciling complex local perspectives regarding restoration, especially relating to sensitive information such as community relations including levels of trust as example, but also adoption of certain practices, trade-offs, yield or revenue, is challenging, with results context specific, unable, per se, to be transferred to other contexts or other scales. Thus, it is critical to consider the context and thus the scale that a framework targets.

Our analysis on FLR assessment frameworks shows that also here frameworks differ with regards to spatial and temporal scale (Fig. 5). The spatial applications of the assessed frameworks range from farm level to national level with some frameworks applicable cross-scales. The majority of the frameworks (n = 12) has applicability at the landscape level. Seven frameworks focus on cross-scale, i.e. being applicable at farm, landscape, and national/sub-national levels. In contrast to cross-scale, which refers to frameworks that include one or more scales, national level refers to frameworks that specifically focus on the national level. Here, ROAM is the only framework that specifically targets national interests, whereby Scaling up greening is solely applicable at the farm level.

Temporally, there are ten frameworks that are applicable explicitly for ex-ante (prior to) FLR implementation, whereby the other 12 are applicable both at ex-ante and ex-post (after) FLR implementation. About half of the frameworks we assess are found to incorporate monitoring and feedback mechanisms. The goal of this inclusion is to ensure that unforeseen constraints are addressed during project lifetime. Furthermore, the monitoring component assists to ensure that implemented measures contribute toward the targeted objective. However, in none of the frameworks is an exit strategy and monitoring beyond life-time an integral component.

3.3 Analysis of existing FLR frameworks

The SWOT mainly base the analysis on the incorporation of the six principles of FLR: focus at landscape level, stakeholder participation, restoration of multiple ecosystem function, tailored to local context, maintain natural ecosystem, and adaptive for long-term resilience. The framework's strength was evaluated based on whether it exclusively or contextually incorporated the six principles. Weaknesses were identified by any neglect or omission of these principles. Opportunities were assessed by examining how the framework could leverage external factors to complement the six principles. Threats were analysed based on potential hindrances or challenges to the framework’s implementation.

Nine FLR frameworks focus on only one principle, whereas five included the maximum number of three principles. Among the frameworks that incorporate only one principle, Tree diversity and Cost benefit Framework for landscape restoration indicate the importance of tailoring FLR to local contexts. Three frameworks, namely Restoration framework for Federal forest, Improving restoration success, and Identifying forest degradation and restoration opportunities fulfil only the principle of focusing at landscape scale. Applicability at specific spatial–temporal scale, neglecting sociocultural values and societal relations including social learning processes, a lack of clear exit strategy as well as mid-term and long-term monitoring and evaluation beyond a project’s lifetime are the most common weakness of the reviewed frameworks.

Thus, our SWOT analysis shows that most frameworks have a very specific focus, placing emphasis mainly on regaining ecological functionality and economic benefit. Only one framework, A guideline for FLR in the tropics have covered all the principles together with their guiding principles to be implemented in the tropics. However, this framework does not specify its applicability to cross regional implementation of FLR in temperate and boreal regions. Integrated approaches are still the minority all reviewed frameworks focusing on a maximum of three FLR principles, the common neglect of social issues. This also links to the level of participation by the respective frameworks.

Stakeholder participation is an integral part of the nine frameworks, which again provide different ways and degrees of participation. From the reviewed frameworks, Scaling Up re-greening, mangrove reforestation and diagnostic for collaborative restoration frameworks explicitly indicate that a diverse range of stakeholders should be included from the beginning of FLR implementation. Although the ROAM framework aims to involve stakeholders, it adopts a predominantly top-down approach that restricts the involvement of project beneficiaries. Despite variations in the extent of their engagement, frameworks advocating for stakeholder participation envision the inclusion of FLR activity beneficiaries from the planning phase through project monitoring and handover. In these processes of stakeholder participation, the learning process should be an integral component of monitoring and evaluation with a strong focus on reflecting on stakeholder interaction processes and the local community’s capacity building as they are the successor. The results from the SWOT analysis based on these principles are illustrated in Fig. 6.

3.4 Social-ecological FLR assessment framework

Overall, we find that a high diversity of frameworks exist to facilitate the planning and implementation of FLR. However, frameworks place different emphasis on ecological, social and economic aspects. While human well-being is a key objective of restoration, social aspects of restoration relating to socio-cultural context, social cohesion but also learning and capacity building are marginalized by current frameworks. Also, exit strategies and monitoring and evaluation with a medium- to long-term perspective beyond a project’s life still are missing in the current frameworks.

Figure 7 summarizes our review results in the form of an integrated FLR assessment framework that aimed at addressing the current limitations. The FLR framework comprises six components that are interlinked: stakeholder participation, customization, time and scale of application, social-ecological balance, monitoring, evaluation and learning, and exit strategy.

-

i. Customization

Some of reviewed frameworks integrate the principle of tailoring to the local context. However, it is not just the application of FLR that should be tailored to local context, but also the procedures, especially those incorporating local knowledge in the planning and implementation processes. Building on the understanding that customization of FLR to the local context is a precondition for FLR success, customization must be applied to the planning, implementation, as well as monitoring and evaluation of FLR activities. This shall help to make FLR best-fit to the local scenarios and options available. Together with the stakeholders, local conditions and needs must be assessed and activities agreed upon in order to then proceed with planning of general FLR activities and implementation processes. The communication strategy must also be tailored to the local context in order to get local citizens to buy-in to the FLR. Our analysis showed here that technicality and need of professional knowledge in applicability of the frameworks as another weakness of existing frameworks.

-

ii. Stakeholder participation

To customize FLR to local needs and foster adoption rates, the principle of stakeholder engagement is key from planning through to evaluation of FLR activities. In order to promote equitable and effective outcomes from FLR implementation, the conditions of the degradation process and restoration should be well understood. Some of the reviewed frameworks did not consider local people’s participation and others did not indicate the extent to which local participation affects the direction of the particular projects in question. However, several elements relating to stakeholder engagement in landscape governance are likely to influence restoration outcomes: who participates in decision-making, at what scales, how policymakers and participants at different scales interact, and how resources are allocated. Co-designing an inclusive FLR approach is key for the entire project life-time and must continue beyond the planning and implementation phase through to monitoring and evaluation.

-

iii. Time and Scale of application

Most of the reviewed frameworks have a specific applicability when it comes to space and time of application. We propose a framework that is applicable across time and scale, thus adjustable and tailored according to context. Using an integrated framework that includes reference to the planning phase, as well as supports monitoring and evaluation of FLR activities, ensures panning of context specific interventions and the opportunity to adjust activities throughout implementation processes.

-

iv. Social-Ecological balance

Most of the reviewed frameworks focus on regaining ecological functionality of the landscape, concentrating more on the ecological goal of restoration. However, as social restoration is also the objective and with increasing evidence on the importance of inclusive restoration and social cohesion for restoration success, fostering levels of trust and collaboration between different actors, and ensuring societal benefits relating to people’s livelihood situations should also be explicitly considered by FLR frameworks in order to secure long-term sustainability of the restored landscape.

-

v. Monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL)

Current frameworks do not yet address exit strategies or plan for monitoring and evaluation beyond the project’s lifetime. Most frameworks refer to evaluation of direct project impacts, neglecting monitoring over time or evaluation on a broader landscape level. Developing indicators for successful restoration targets in monitoring and evaluation component is vital. Also the aspect of learning and capacity building are still marginalized, though both crucial for critical reflection of context and processes as well as to foster FLR beyond a project’s lifetime. This means that, in practice, capacities (funding) need to be allocated to monitoring, evaluation and learning and that there should also be the possibility to run impact studies after project completion and on a larger scale.

-

vi. Exit strategy

Exit strategies are not part of existing FLR frameworks yet. To facilitate the continuance of FLR activities beyond a project’s lifetime, it is key to integrate an exit strategy from project planning onwards facilitating gradual handover to the local community. This makes continuous and high degree of participation key, as well as the element of learning based on capacity building and critical reflection of processes throughout the project’s life-time is key for defining and following sustainable exit strategies. Having this adaptive monitoring of the people’s involvement and a strong element of learning as integral part of the FLR process from the very beginning provides for a smooth exit by the handing over of interventions to the local community.

4 Discussion

The results show that there is a strong focus on ecological and biodiversity regaining as compared to economic and social values for the people living in the landscape. Similarly, Mansourian and Parrotta [29] uncover that, since the initiation of FLR, reconciling the different values and objectives of FLR is an ongoing, major challenge. Surprisingly, only one framework (A restoration framework for federal forests) mentions building local community resilience to climate change. One of the strongly identified areas of focus, in addition to the environmental issues, is the economic dimension. This is simply because, although FLR activities helps to restore degraded forest landscapes and improve biodiversity in the long run, the penultimate benefit of FLR is for human benefit. Studies indicate that FLR fundamentally seeks to balance the environmental and social-economic needs of people through different restoration activities [25, 47]. Essentially, the concept of FLR entails restoring ecological functionality and enhancing human well-being, balancing the environmental state of the landscape and the socio-economic conditions of the local community. Therefore, there is a strong emphasis on the possible economic benefits from FLR and/or that its outcome should not compromise the economic returns of people who depend on forest resources.

Four principles facilitating restoration are already recommended: promoting ecological integrity; establishing self-sustaining and resilient systems; being informed about the past and future; and being beneficial and engaging society [48, 49]. The ability of farmers to prevent, accommodate or recover from disasters or crises is one of the indicators for famers to be resilient [50]. Hence, farmers who practice agroforestry systems, like FLR, have a potential to diversify both food and economic resources. Here restoration approaches and practices, contribute toward improved income and yield availability throughout the year. Further, diversified farm productions can support availability and access to food alongside a more balanced and nutritious diet. Whilst economic benefits are assumed to inherently impact positively on people’s livelihood situation, we argue that the social dimensions of restoration need to be addressed more explicitly. Other studies also support these findings, showing that improvements in socio-cultural context and social cohesion, the status of participation of youth, women, and minorities, human health, strengthening local communities, and restoration of dialogue and trust are critical leverage points for the successful long-term management of protected areas. [14]. The need to pay explicit attention to community relations and people’s livelihoods is also underlined by the finding that many of those priority areas for restoration that have experienced political instability in the past are unstable today [22].

Addressing more explicitly the social dimensions of restoration can facilitate FLR to positively impact community relations, including trust and collaboration, as well as more equal access to, and distribution of, resources, thereby also making communities more resilient to external shock [51]. Whilst in the already recommended principles, resilience primarily relates to resilience to climate change-induced risks, such as drought and floods, resilience can also relate to societal resilience to absorb shocks relating for example to political instability, financial crises or health (e.g. COVID pandemic). In conflict-affected scenarios, restoration through co-design or co-governance, for example, also has the potential to create spaces for enhanced stakeholder communication and collaboration. This would contribute to growing trust among community members which again can facilitate the exchange of information, willingness to work together and support each other, as well as the ability to raise issues of discontent and negotiate [51]. Addressing social aspects explicitly while implementing FLR can also contribute to enhanced trust between FLR project implementers and the local community further engaging them in the implementation process and facilitating a smooth transition following the project phase out. However, such processes need to be implemented and supported carefully as there is also danger of unintended negative consequences such as community dependency on external support, misallocation of resources and social conflicts.

None of the reviewed frameworks explicitly mention customization. Some frameworks state the importance of ecological context when planning FLR [5]. Tailoring to local context offers a way to expand opportunities, while simultaneously facilitating a deeper understanding of stakeholder preferences, “thus integrated in the planning” [5, 6]. Scaling-up the locally recognized restoration practices can lead to higher success as a result of acceptability by the community. Adapting restoration strategies to fit to local social economic and ecological contexts is emphasized as one of the guiding principles for FLR projects [6, 11, 52]. Our integrated FLR framework specifically promotes the equal consideration of social inclusion alongside ecological emphasis. Similarly, Besseau, Graham [46] conclude that community relations and social integration in FLR is vital for regaining ecological functionality.

In order to enhance contributions to social dimensions, land planning institutions should follow principles of inclusiveness, actively adapting protocols to consider existing social values and norms thus facilitating a proper response to social, economic, and environmental realities. The social-ecological system complexity of the landscapes can be an opportunity for FLR projects if various methods are applied and a portfolio of diverse goals are set [6]. Löfqvist, Kleinschroth [15] argue that social considerations at the center of restoration planning, decision making, and implementation can contribute highly to reducing the risk that restoration interventions exacerbate poverty and income inequality. Hence, social-ecological balance increases the chance that the local community is empowered and benefits from the restoration action. A restoration effort focused solely on conservation, neglecting human well-being, will likely struggle with community adoption and implementation. Conversely, incorporating a balanced social perspective in ecological restoration significantly increases the likelihood of community engagement and FLR long-term success. Calling for stronger emphasis on social restoration will not diminish the importance of ecological restoration; rather it is understood as a call for a more context- dependent, inclusive and balanced approach that creates an iterative and self-enforcing win–win situation for the social and ecological dimension of restoration.

Of all the frameworks reviewed, only the Governance and Forest landscape restoration framework explicitly explores power relations. Some of the frameworks are very technical in nature and are only able to be comprehended by a few professionals. Participation by a diverse range of stakeholders expressing their opinions ensures the long term success of an FLR project. Thereby, it is important to consider issue of power imbalances and capacities of stakeholders to voice their concerns and even their discontent. The intention of integrating local people’s and diverse stakeholder groups’ perspectives is increasing in the protected area management intervention process [16, 17]. Power imbalances between stakeholders involved in the process of FLR implementation could be a source of conflict [53]. The current trend of FLR implementation does not fully engage the local community in the process of FLR project scoping and its implementation even though they are expected to take over after the project’s completion.

It is important to map all stakeholders, not just the beneficiaries and actively engaged, but also those who would be negatively impacted by the FLR activity [54, 55]. Therefore, efforts should be made to ensure that minorities and the local community groups are part of the process [56]. This has implications not only on allowing people to enter in joint discussions and planning processes, but to also reflect critically on language and capacities relating to time and needs. Language and information shared should not be too technical but be adjusted to context-dependent needs. Depending on the stakeholders’ background, it might be necessary to build up capacities that empower participants to voice their needs as well as concerns and discontent. Additionally, participation requires time that participants could invest on other work, such as income generating activity or domestic work including child care. This needs to be considered carefully when planning meetings and possible compensation schemes or child care support measures considered.

It is clear that forest landscape restoration extends far beyond the project funding period, thus requiring the integration of adaptive management that include monitoring and effective feedback to make necessary corrections and further interventions [6]. Multiple authors identify ‘local incentives and motivations’ as one of the most important issues to address in collaborative monitoring for FLR [6, 57, 58]. A diagnostic framework for collaborative monitoring calls for at least two levels of application from highlighting key factors that are specific to FLR site to multilevel collaborative monitoring system to be considered [59]. It is emphasized that frameworks serve to determine and prioritize restoration needs across a landscape system; they also facilitate ongoing monitoring to achieve land management goals [60]. Community members need to be integrated in designing, monitoring, and evaluation strategies. Local people should take key roles, especially when considering FLR impact on the societal level (people’s livelihoods situation and social cohesion) alongside their attitudes toward FLR approaches and practices. Further their motivation and ability to continue beyond the project’s lifetime should be considered. However, the process is highly subject to trained field teams to conduct the activity. Local people should be given the opportunity to monitor FLR projects with good capacity building component integrated to provide sufficient trainings on FLR monitoring [59]. Furthermore, our framework paper highlights on integrating learning component alongside monitoring and evaluation where the local community should adaptively takeover the restoration project. This coincides with Pasanen, Ambrose [61] who suggest that learning has to be captured through the project lifetime as it is important for strengthening relationships with key stakeholders. In this aspect, the local community adaptively monitors FLR through learning by doing technique [62].

5 Conclusion and recommendations

Application of our integrated FLR framework requires that policymakers and practitioners allow the allocation of more time and resources to the planning phase and the post-intervention phase. Since policy-making should involve all stakeholders and closely consult the local community, the framework will contribute to the FLR policy-making process and principles. This will be particularly important for engaging stakeholders and establishing a monitoring and evaluation, principles of tailoring to local context and exit strategy for FLR projects. While planning activities directly link to individual FLR projects, broader stakeholder dialogue processes should be made an integral part of FLR project budgets. This may require an adjustment of FLR toolboxes, incorporating more participatory methods that bring together diverse stakeholder groups before and during FLR implementation for co-design and implementation and governance, including monitoring and evaluation.

Post-intervention monitoring and evaluation could be more difficult to fund and ensure. Here different pathways are thinkable: multiple organizations and bodies could engage in resource pooling to fund and conduct post-intervention evaluations at regular intervals on a landscape rather than individual project level. Alternatively, policymakers could allocate (more) funding to an evaluation and monitoring pool that is used at regular intervals to assess impacts of past projects. Different platforms and approaches already exist to which documentation and monitoring should even be expanded further, including, among others, "Supporting the Design and Implementation of the UN Decade of Ecosystem Restoration" (DEER) platform [63] and the panorama restoration solution, coordinated by GIZ and IUCN. The AFR100 and comparable bodies could be excellent platforms to document and share FLR approaches and lessons learned. There must be more collaboration between science, policy, and practice, including in particular local actors.

This could be justified due to the need of national governments to report on progress against national, regional, and international FLR targets. Alternatively, a monitoring and evaluation budget pooled by regional bodies and their members, such as of members of the AFR100 and coordinated and distributed by the AFR100 directory could be another governance mechanism. However, these supra-national or even national structures bear the danger that standardized assessments are conducted by external evaluators, thereby missing the principle of stakeholder participation in the monitoring and evaluation activities.

Based on our literature review of leading FLR assessment frameworks and identified gaps, we propose an integrated FLR framework that supports the participatory design and implementation of context-specific FLR interventions that target ecological as well as social restoration with a long-term perspective. Broad applicability of the framework must be tested. Best-practice examples and lessons-learned, especially in relation to social-ecological approaches, must be collected and shared with restoration stakeholders to maximize FLR success. This applies to experience with specific tools and the learning process with stakeholders; thereby extending the principle of learning beyond the individual project and fostering a knowledge pool for reflection and improvements within the diverse FLR actors.

In conclusion, the framework paper significantly supports the following Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). SDG 13: Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts by promoting engagement and sustainable cooperation in implementing Forest and Landscape Restoration (FLR) initiatives. SDG 15: Encourage the implementation of FLR while promoting sustainable forest use in the restoration of degraded forests and landscapes. SDG 17: Partnerships for the goals: It fosters a transparent FLR implementation process by integrating six FLR principles and designing project exit strategies, thereby building trust and cooperation in fulfilling global commitments.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Pistorius T, Carodenuto S, Wathum G. Implementing forest landscape restoration in Ethiopia. Forests. 2017;8(3):61.

Pistorius T, Freiberg H. From target to implementation: perspectives for the international governance of forest landscape restoration. Forests. 2014;5(3):482–97.

Mansourian S, Vallauri D. Forest restoration in landscapes: beyond planting trees. New York: Springer Science & Business Media; 2005.

Stanturf JA, Mansourian S. Forest landscape restoration: state of play. Royal Soc Open Sci. 2020;7(12):201218.

Mansourian S. Governance and forest landscape restoration: a framework to support decision-making. J Nat Conserv. 2017;37:21–30.

Stanturf JA, Kleine M, Mansourian S, Parrotta J, Madsen P, Kant P, et al. Implementing forest landscape restoration under the Bonn challenge: a systematic approach. Ann For Sci. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-019-0833-z.

solution pr. https://panorama.solutions/en/portal/panorama-restoration2023. Accessed 15 Nov 2023.

Mansourian S, Walters G, Gonzales E. Identifying governance problems and solutions for forest landscape restoration in protected area landscapes. Parks. 2019;25(1):83–96.

Van Oosten C. Restoring landscapes—governing place: a learning approach to forest landscape restoration. J Sustain For. 2013;32(7):659–76.

Mansourian S, Vallauri D, Dudley N, Dudley N, Mansourian S, Vallauri D. Forest landscape restoration in context. In: Forest restoration in landscapes: beyond planting trees. Berlin: Springer; 2005. p. 3–7.

Iucn W. A guide to the restoration opportunities assessment methodology (ROAM): assessing forest landscape restoration opportunities at the national or sub-national level. Gland: IUCN; 2014.

Cantarello E, Newton AC, Hill RA, Tejedor-Garavito N, Williams-Linera G, López-Barrera F, et al. Simulating the potential for ecological restoration of dryland forests in Mexico under different disturbance regimes. Ecol Model. 2011;222(5):1112–28.

Slobodian L, Vidal A, Saint-Laurent C. Policies that support forest landscape restoration: what they look like and how they work. Gland: IUCN; 2020.

Cebrián-Piqueras MA, Palomo I, Lo VB, López-Rodríguez MD, Filyushkina A, Fischborn M, et al. Leverage points and levers of inclusive conservation in protected areas. Ecol Soc. 2023. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-14366-280407.

Löfqvist S, Kleinschroth F, Bey A, de Bremond A, DeFries R, Dong J, et al. How social considerations improve the equity and effectiveness of ecosystem restoration. Bioscience. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biac099.

Oldekop JA, Holmes G, Harris WE, Evans KL. A global assessment of the social and conservation outcomes of protected areas. Conserv Biol. 2016;30(1):133–41.

Zafra-Calvo N, Balvanera P, Pascual U, Merçon J, Martín-López B, van Noordwijk M, et al. Plural valuation of nature for equity and sustainability: Insights from the Global South. Glob Environ Chang. 2020;63: 102115.

Elias M, Kandel M, Mansourian S, Meinzen-Dick R, Crossland M, Joshi D, et al. Ten people-centered rules for socially sustainable ecosystem restoration. Restor Ecol. 2022;30(4): e13574.

Kassa H, Birhane E, Bekele M, Lemenih M, Tadesse W, Cronkleton P, et al. Shared strengths and limitations of participatory forest management and area exclosure: two major state led landscape rehabilitation mechanisms in Ethiopia. Int For Rev. 2017;19(4):51–61.

Chazdon RL, Lindenmayer D, Guariguata MR, Crouzeilles R, Benayas JMR, Chavero EL. Fostering natural forest regeneration on former agricultural land through economic and policy interventions. Environ Res Lett. 2020;15(4):043002.

Stanturf JA. Forest landscape restoration: building on the past for future success. Restor Ecol. 2021;29(4): e13349.

Frietsch M, Loos J, Löhr K, Sieber S, Fischer J. Future-proofing ecosystem restoration through enhancing adaptive capacity. Commun Biol. 2023;6(1):377.

Kittinger JN, Bambico TM, Minton D, Miller A, Mejia M, Kalei N, et al. Restoring ecosystems, restoring community: socioeconomic and cultural dimensions of a community-based coral reef restoration project. Reg Environ Change. 2016;16(2):301–13.

Sigman E, Elias M. Three approaches to restoration and their implications for social inclusion. Ecol Restor. 2021;39(1–2):27–35.

Chazdon RL, Wilson SJ, Brondizio E, Guariguata MR, Herbohn J. Key challenges for governing forest and landscape restoration across different contexts. Land Use Policy. 2021;104:104854.

Buckingham K, Ray S, Morales AG, Singh R, Martin D, Wicaksono S, et al. Mapping social landscapes: A guide to identifying the networks, priorities, and values of restoration actors. 2018.

Brown MJ, Zahar M-J. Social cohesion as peacebuilding in the Central African Republic and beyond. J Peacebuilding Dev. 2015;10(1):10–24.

Ros-Tonen MA, Derkyi M. Conflict or cooperation? Social capital as a power resource and conflict mitigation strategy in timber operations in Ghana’s off-reserve forest areas. Ecol Soc. 2018. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-10408-230344.

Mansourian S, Parrotta J. Forest landscape restoration: integrated approaches to support effective implementation. Milton Park: Routledge; 2018.

Stanturf JA, Palik BJ, Williams MI, Dumroese RK, Madsen P. Forest restoration paradigms. J Sustain For. 2014;33(sup1):S161–94.

Bouchard M, Garet J. A framework to optimize the restoration and retention of large mature forest tracts in managed boreal landscapes. Ecol Appl. 2014;24(7):1689–704.

Maron M, Hobbs RJ, Moilanen A, Matthews JW, Christie K, Gardner TA, et al. Faustian bargains? Restoration realities in the context of biodiversity offset policies. Biol Cons. 2012;155:141–8.

Mansourian S. From landscape ecology to forest landscape restoration. Landscape Ecol. 2021;36:2443–52.

Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Chandler J, Welch VA, Higgins JP, et al. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.ED000142.

Booth A, Sutton A, Clowes M, Martyn-St JM. Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. Newcastle upon Tyne: Sage; 2021.

Gitz V, Place F, Koziell E, Pingault N, van Noordwijk M, Meybeck A, et al. A joint stocktaking of CGIAR work on forest and landscape restoration. Bogor: CIFOR; 2020.

Chazdon RL, Guarigueta M. Decision support tools for forest landscape restoration. Bogor Barat: CIFOR; 2018.

C. C. Connected paper. https://www.connectedpapers.com/. Accessed 27 May 2022.

César RG, Belei L, Badari CG, Viani RA, Gutierrez V, Chazdon RL, et al. Forest and landscape restoration: a review emphasizing principles, concepts, and practices. Land. 2020;10(1):28.

Mayring P. Qualitative content analysis: theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. 2014; 143

Kohlbacher F. The use of qualitative content analysis in case study research. Forum qualitative sozialforschung/forum: Qualitative social research; Institut fur Klinische Sychologie and Gemeindesychologie. 2006:7(1):1-30.

Mayring P. Qualitative content analysis. Compan Qual Res. 2004;1(2):159–76.

Rädiker S, Morgenstern-Einenkel A. Working in teams with MAXQDA: Organization, division of. 2021.

Kuckartz U. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: von Kracauers Anfängen zu heutigen Herausforderungen. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 2019;20(3).

Benzaghta MA, Elwalda A, Mousa M, Erkan I, Rahman M. SWOT analysis applications: An integrative literature review. J Glob Bus Insights. 2021;6(1):55–73.

Besseau P, Graham S, Christophersen T. Restoring forests and landscapes: the key to a sustainable future. Global Partnership on Forest and Landscape Restoration, Vienna, Austria ISBN, (978–3). 2018:902762–97.

Kumar C, Begeladze S, Calmon M, Saint-Laurent C. Enhancing food security through forest landscape restoration: lessons from Burkina Faso, Brazil, Guatemala, Viet Nam, Ghana, Ethiopia and Philippines. Gland: IUCN; 2015. p. 5–217.

Dey DC, Schweitzer CJ. Restoration for the future: endpoints, targets, and indicators of progress and success. J Sustain For. 2014;33(sup1):S43–65.

Suding K, Higgs E, Palmer M, Callicott JB, Anderson CB, Baker M, et al. Committing to ecological restoration. Science. 2015;348(6235):638–40.

Field CB. Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation: special report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2012.

Löhr K, Aruqaj B, Baumert D, Bonatti M, Brüntrup M, Bunn C, et al. Social cohesion as the missing link between natural resource management and peacebuilding: lessons from cocoa production in Côte d’Ivoire and Colombia. Sustainability. 2021;13(23):13002.

Kassa H, Abiyu A, Hagazi N, Mokria M, Kassawmar T, Gitz V. Forest landscape restoration in Ethiopia: progress and challenges. Front For Glob Change. 2022;5:796106.

Brancalion PH, Chazdon RL. Beyond hectares: four principles to guide reforestation in the context of tropical forest and landscape restoration. Restor Ecol. 2017;25(4):491–6.

Verdone M. A cost-benefit framework for analyzing forest landscape restoration decisions. Gland: IUCN; 2015. p. 42.

Stanturf J, Madsen P, Lamb D. A goal-oriented approach to forest landscape restoration. Dordrecht: Springer Science & Business Media; 2012.

Dudley N, Baker C, Chatterton P, Ferwerda W, Gutierrez V, Madgwick J. The 4 returns framework for landscape restoration. Commonland, Wetlands, International Landscape finance Lab & IUCN Commission on Ecosystem Management: Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 2021.

Turreira-García N, Meilby H, Brofeldt S, Argyriou D, Theilade I. Who wants to save the forest? characterizing community-led monitoring in Prey Lang Cambodia. Environ Manag. 2018;61(6):1019–30.

Guariguata MR, Evans K. A diagnostic for collaborative monitoring in forest landscape restoration. Restor Ecol. 2020:28(4);742–749.

Evans K, Guariguata M. A diagnostic for collaborative monitoring in forest landscape restoration. Bogor: CIFOR; 2019.

Ciecko LA, Kimmett D, Saunders J, Katz R, Wolf KL, Bazinet O, et al. Forest Landscape Assessment Tool (FLAT): rapid assessment for land management: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research. 2016.

Pasanen T, Ambrose K, Batool S, Soumelong LE, Abuya R, Mountfort H, et al. Outcome monitoring and learning in large multi-stakeholder research programmes: lessons from the PRISE consortium. Pathways to Resilience in Semi-arid Economies. 2018.

Price-Kelly H, Hammill A, Dekens J, Leiter T, Olivier J. Developing national adaptation monitoring and evaluation systems: a guidebook. Geneva: IISD: International Institute for Sustainable Development; 2016.

Restoration UNDfE. Framework for ecosystem restoration monitoring FAO; 2024.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted in the frame of TREES project Tropical Restoration Expansion for Ecosystem Services, Accompanying research to Forest Landscape Restoration and Governance in the Forest sector (F4F) coordinated by the German Leibniz Centre for Agricultural Landscape Research (ZALF). This work received financial support from the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) commissioned and administered through the global project on forest landscape restoration and good governance in the forest sector (Forests4Future) of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ). The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of the authors of this publication and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of F4F/GIZ or the BMZ. We thank the reviewers for their feedback that helped us improve our work.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work received financial support from the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) commissioned and administered through the global project on forest landscape restoration and good governance in the forest sector (Forests4Future) of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KL, SBE conceived and designed the research; KL, SBE, HM, JAH performed literature review KL, SBE, HM, JAH, AT, KH, HR analysed the data; KL, SBE wrote the original draft of the manuscript; KL, SBE, StS, HM, JAH, HRR, TB, AK, KK reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Löhr, K., Eshetu, S.B., Moluh Njoya, H. et al. Toward a social-ecological forest landscape restoration assessment framework: a review. Discov Sustain 5, 155 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00342-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00342-y