Abstract

In the face of climate change, people experience a variety of emotions, e.g., guilt, grief, anger, anxiety, or even shock. Although these emotions are generally considered unpleasant, they may play a key role in dealing with climate change by motivating climate action. In 2022, Ágoston et al. introduced three questionnaires to assess eco-guilt (EGuiQ-11), ecological grief (EGriQ-6), and eco-anxiety (EAQ-22). We translated and validated these questionnaires in a large German sample (N = 871). More specifically, the current study not only intended to replicate the factor structures of all three questionnaires, but also expand previous findings by investigating associations of eco-emotions with climate action intentions, climate policy support, climate anxiety, and psychological distress. Confirmatory factor analyses indicated one-factor structures of the EGuiQ-11 and EGriQ-6 and the two factors habitual ecological worry and negative consequences of eco-anxiety of the EAQ-22. All eco-emotions were positively associated with climate action intentions and climate policy support, but also with levels of climate anxiety as well as general anxiety and depression. All in all, the translated questionnaires seem suitable measurements of eco-guilt, ecological grief, and eco-anxiety that capture the adaptive and maladaptive aspects of these emotions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The devastating consequences of ecological crises, such as climate change, do not only impact the natural environment but also people’s affective states. Accordingly, individuals experience, for instance, guilt [1], anxiety [2], grief [3], anger [4], but also hope [5] in the face of environmental issues. These eco-emotions have been conceptualized as affective reactions to various environmental crises and accordingly include but are not limited to climate change related emotions [6]. Despite individual differences, most people seem to encounter eco-emotions to some extent [7, 8] leading to an increasing scientific and public interest in the affective dimension of ecological crises. Furthermore, eco-emotions may not only be a consequence of environmental degradation but also a motivator of pro-environmental behavior [9]. According to theories on affect (e.g., [10]), emotions are key antecedents of human behavior. Negative emotions, in particular, can function as signals of frustrated basic needs (e.g., need for safety), which in turn motivate appropriate countermeasures [11]. In line with these theoretical considerations, a meta-analysis [12] on potential motivators of adaptive climate change behavior revealed negative affect as one of the most predictive variables. However, eco-emotions may not only motivate but also overwhelm individuals. Accordingly, high levels of negative climate-related emotions were associated with insomnia and worse overall mental health [13].

Despite the increasing interest in eco-emotions, previous research [14] discussed several methodological issues regarding the cross-sectional measurement of these affective states. For example, many instruments are limited to the measurement of only one emotion. While the literature on environmental psychological research offers a variety of well validated questionnaires on anxiety-related experiences, e.g., the Climate Anxiety Scale [15], the Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale [16], or the Climate Change Worry Scale [17], comparatively fewer instruments on other eco-emotions are available. Hence, empirical studies may not adequately capture the complexity and multitude of relevant eco-emotions suggested by recent theoretical accounts [6].

Furthermore, many questionnaires seem to focus on the potentially pathological consequences rather than the adaptive aspects of eco-emotions. For example, the Climate Anxiety Scale [15] is based on measures of clinical symptoms, especially rumination and functional impairment. Similarly, the Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale [16] is based on a symptom-oriented theoretical foundation by linking eco-anxiety to the characteristics of general anxiety disorder. However, the clinical relevance of eco-emotions is frequently discussed in recent literature on affective environmental research [18,19,20]. For example, levels of climate anxiety were on average low in a German [21] and UK sample [22]. Consequently, questionnaires on eco-emotions should not be limited to the maladaptive features of these experiences.

In an attempt to measure various aspects of multiple eco-emotions, i.e., eco-guilt, ecological grief, and eco-anxiety, Ágoston, Urbán, et al. [14] introduced three questionnaires: the Eco-Guilt Questionnaire (EGuiQ-11), the Ecological Grief Questionnaire (EGriQ-6), and the Eco-Anxiety Questionnaire (EAQ-22). Eco-guilt refers to the affective state most individuals experience after violating personal or societal norms for environmental behavior [23]. Hence, eco-guilt is based on feelings of responsibility that are especially prevalent in young people [24]. Grief is often understood as emotional reaction to experiences of loss [25]. Accordingly, ecological grief, is defined as grief in reaction to environmental loss [3]. These experiences are not exclusively based on physical loss (e.g., the disappearance or degradation of eco-systems), but also loss of knowledge systems and identity, or anticipated environmental losses. Finally, eco-anxiety has been defined as fear or worry of environmental doom (for an overview, see [26]). Previous research identified eco-anxiety as a multifaceted phenomenon that can range from constructive worry [20] to pathological anxiety, which includes symptoms of persistent worrying, restlessness, or concentration difficulties [27].

Although the EGuiQ-11, the EGriQ-6, and the EAQ-22 [14] were thoroughly constructed and validated in a multi-step process, they are limited to the use in Hungarian-speaking populations. The availability of psychometrically sound instruments in multiple languages seems especially relevant in the light of cross-cultural differences regarding negative climate related emotions indicated by previous research [13]. Therefore, in the present study, we analyze the factor structure and construct validity of all three questionnaires in German to enable further research of eco-emotions in German-speaking populations. We aim to not only replicate but also expand the results of Ágoston, Urbán et al. [14] by investigating associations with theoretically related constructs, i.e., climate anxiety [15], climate action intentions [28], climate policy support [21], and psychological distress [29].

2 Potential correlates of eco-emotions

2.1 Eco-emotions and climate anxiety

Climate anxiety has been conceptualized as a specific form of eco-anxiety specifically related to anthropogenic climate change [6]. While the Climate Anxiety Scale [15] mainly operationalizes climate anxiety on a symptom level, the EAQ-22 [14] offers two subscales to address the adaptive and maladaptive facets of eco-anxiety, i.e., habitual ecological worry and negative consequences of eco-anxiety. Conceptually, the subscale negative consequences of eco-anxiety seems closely related to the items of the Climate Anxiety Scale by assessing anxiety-related impairments. As an indicator of construct validity [30], we therefore hypothesize that the negative consequences of eco-anxiety subscale correlates strongly and positively with climate anxiety (H1a). On the other hand, the habitual ecological worry subscale was designed to reflect the more constructive aspects of eco-anxiety in contrast to the more pathologically oriented Climate Anxiety Scale. Although both scales assess anxiety-related experiences, we therefore expect only a low positive correlation between the habitual ecological worry subscale and climate anxiety (H1b). Although previous taxonomies [26] suggest a co-occurrence of negative eco-emotions, only little empirical research has been dedicated to these potential interrelations. In their validation study, Ágoston, Urbán, et al. [14] revealed positive associations between eco-guilt, ecological grief, and both facets of eco-anxiety. Similarly, we hypothesize positive correlations of both eco-guilt and ecological grief with climate anxiety (H1c).

2.2 Eco-emotions and climate action

Negative eco-emotions have been identified as strong motivators of climate action in particular [for an overiew, see 9] and pro-environmental behavior in general [31]. Accordingly, a meta-analysis [1] revealed moderate correlations of anticipated guilt with both reported and intended pro-environmental behavior. The causality of this association was supported by several experimental studies. For example, individuals who were induced with a guilty conscience via short texts about environmental damages were more likely to sign a pro-environmental petition [32]. Similarly, individuals who received false feedback in a carbon footprint calculator reported stronger feelings of guilt, which resulted in increased subsequent pro-environmental behavior [33].

Certain solution-oriented forms of eco-anxiety, often referred to as practical eco-anxiety [19] or constructive worry [20] have also been associated with increased pro-environmentalism. Correlational studies, for example, identified worry about climate change as an important predictor of support for climate policy [34, 35]. Furthermore, experimentally induced worry via personal stories positively influenced global warming beliefs and risk perceptions [36]. Interestingly, climate anxiety measured via Climate Anxiety Scale was unrelated to engagement in environmental issues in the original validation study [15], but positively correlated with climate action intentions and climate policy support in the German version [21].

Although ecological grief has been theorized as a potentially adaptive response to ecological crises and a motivator of pro-environmental behavior [18], empirical evidence for this functionality seems to be scarce. In an experimental study [37], individuals who were confronted with sadness inducing videos spent more time on a subsequent carbon footprint calculator and donated more money to an environmental organization. However, this effect was only found for immediate and not delayed reactions to the sadness manipulation. In their validation study of the EGuiQ11, EGriQ-6, and EAQ-22, Ágoston, Urbán, et al. [14] revealed small but significant positive correlations of eco-guilt, ecological grief, and eco-anxiety with various self-reported pro-environmental behaviors. As a replication and expansion of these findings, we expect eco-guilt, ecological grief, and both facets of eco-anxiety to be positively correlated with climate action intentions and climate policy support (H2).

2.3 Eco-emotions and psychological distress

Aside from the motivational aspects of eco-emotions, strong and lasting emotional responses to ecological crises may also have a negative impact on general mental health. In light of a high comorbidity of anxiety disorders and depression [38], high levels of eco-anxiety may be similarly related to depressive symptoms, e.g., anhedonia, fatigue, or sleep disorders. Accordingly, climate anxiety was associated with elevated (yet mostly non-clinical) levels of depression and general anxiety [15, 21] as well as insomnia [13]. To our knowledge, there is little quantitative research on potential associations between psychological distress and both eco-guilt and ecological grief. Regarding eco-guilt, however, previous qualitative studies suggest that feeling overly guilty with one’s past behavior may result in self-criticism and less well-being [39]. Although grief is a common emotional reaction to loss, previous research identified pathological forms of grief reactions including complicated or chronic grief as well as associations with depression [40]. Ecological grief was associated with traumatic experiences and may consequently likewise cause symptoms of depression or posttraumatic stress disorder [3, 18]. Due to these findings, we expect positive correlations of eco-guilt, ecological grief, and (negative consequences of) eco-anxiety with psychological distress (H3).

3 Methods

3.1 Participants and procedure

This study was realized on the online platform SoSci Survey [41] and distributed to a convenience sample in the online respondent pool SoSci Panel [42]. A priori power calculations yielded a sample size of 880 participants to ensure an N:q ratio of 20:1 recommended for confirmatory factor analyses [43]. After providing informed consent via opt-in buttons, 933 participants completed the study. The items within each eco-emotion questionnaire were presented in randomized order to account for item order effects [44].

For the factor analyses, we excluded 35 participants with missing values on the eco-emotion questionnaires and 27 speeders (relative speed index > 2; [45]), yielding a total sample size of N = 871.Footnote 1 The mean age was 49.3 years (SD = 15.3); 56.4% of participants identified as female, 42.7% as male, and 0.9% as diverse. Most participants indicated an academic degree as highest education (89.1% college or higher), were employed (69.9%), and earned a net income of over 2000€ per month (52.6%; for detailed demographic information, see Supplement S1). We conducted this study in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the ethics committee of the Johannes Gutenberg-University Mainz (2023-JGU-psychEK-S020).

3.2 Measures

3.2.1 Eco-guilt, ecological grief, and eco-anxiety

The three questionnaires by Ágoston, Urbán, et al. [14] assess eco-guilt (EGuiQ-11; e.g., “I feel guilty for not paying enough attention to the issue of climate change”), ecological grief (EGriQ-6; e.g., “It makes me sad that I don’t see many of the plants and animals I used to see often”), and eco-anxiety (EAQ-22; e.g., “It scares me that the weather is becoming more and more unpredictable because of climate change”) on 4-point Likert scales (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). Ágoston, Urbán, et al. suggest two factors within the EAQ-22, i.e., habitual ecological worry (e.g., “I am worried about the increasing number of natural disasters caused by climate change”) and negative consequences of eco-anxiety (e.g., “I am so anxious about climate change that it affects my performance at school/work”). All items were translated into German and back-translated into English by two professional translators of the Johannes Gutenberg-University Mainz. The back-translation method revealed only minor wording incongruities, which we resolved via discussion (for an overview of all translated items, see Supplement S2).

3.2.2 Climate anxiety

We assessed climate anxiety with the German version of the Climate Anxiety Scale [CAS; 21]. The CAS consists of 13 items regarding climate change related impairments that are rated on 7-point Likert scales (1 = does not apply at all to 7 = applies completely). Although the original version of the CAS [15] suggests two subscales, i.e., cognitive-emotional impairment (e.g., “I find myself crying because of climate change”) and functional impairment (e.g., “I have problems balancing my concerns about sustainability with the needs of my family”), the German version was not able to replicate these factors. Therefore, we calculated a total score of climate anxiety by averaging all 13 items of the CAS for all analyses (α = 0.86).

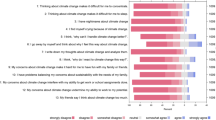

3.2.3 Climate action intentions

Climate action intentions were assessed via three items [21, 28]. Participants rated statements on behavior change intentions regarding political and activist engagement (“I plan to become involved in politics in the future to limit the consequences of climate change”, “I plan to become involved in activism in the future to limit the consequences of climate change”) and everyday behavior (“I plan to act in an environmentally protective way in my everyday life in the future to limit the consequences of climate change”) on 7-point Likert scales (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree; α = 0.76).

3.2.4 Policy support

We developed three items to assess support for climate protection policies that were included in the governmental climate protection program [46] and debated in Germany at the time of data acquisition (“Expansion of renewable energies”, “Speed limit of 120 km/h on all German highways”, “Ban on newly installed oil and gas heating systems as of 2024”; α = 0.73). Participants indicated policy support on 7-point Likert scales (1 = strongly disapprove to 7 = strongly approve).

3.2.5 Psychological distress

The Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4; [47]) was included as an indicator of psychological distress with the subscales general anxiety and depression (α = 0.88). Both subscales assess key symptoms within the past two weeks via two 4-point Likert items each (e.g., “Not being able to stop or control worrying “; “Little interest or pleasure in doing things”; 0 = not at all to 3 = nearly every day).

4 Results

We used SPSS 27 [48] to analyze descriptive and correlational statistics, and performed confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) with MPLUS 7.3 [49].

4.1 Factor structure of the EGuiQ-11, EGriQ-6, and EAQ-22

Similar to Ágoston, Urbán, et al. [14] and based on established conventions [50, 51], we determined model fit by investigating χ2-test statistics,Footnote 2 the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; acceptable < 0.08), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; acceptable > 0.90), and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI; acceptable > 0.90). All CFAs were performed with weighted least square mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimation, which was found to yield more robust estimates for items with few categories [52].

4.1.1 Eco-Guilt questionnaire (EGuiQ-11)

With respect to the EGuiQ-11, the CFA identified the hypothesized one-factor solution with satisfactory fit. While the χ2-test of model fit was significant χ2 (44, N = 871) = 217.05, p < 0.01, RMSEA = 0.067, 90% CI [0.058, 0.076] indicated acceptable fit and both CFI = 0.989 and TLI = 0.987 indicated excellent fit. All items had salient factor loadings (≥ 0.05; for an overview, see Table 1). The internal consistency of the EGuiQ-11 was excellent (α = 0.93).

4.1.2 Ecological grief questionnaire (EGriQ-6)

The one-factor model of the EGriQ-6 was identified but did not exhibit satisfactory fit. Although CFI (0.977) and TLI (0.961) were high, RMSEA was unacceptable (0.119, 90% CI [0.101, 0.139]), χ2 (9, N = 871) = 120.50, p < 0.001. We ran an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with oblique rotation to test whether a two-factor model would better fit the data. Indeed, the two-factor solution yielded acceptable model fit, RMSEA = 0.056, 90% CI[0.027, 0.087], CFI = 0.998, TLI = 0.992, χ2 (4, N = 871) = 14.736, p < 0.01. However, one item did not have salient factor loadings and another item had high cross loadings (see Supplement S3). As the exclusion of these items would lead to instable factors with only two items each [53], we examined correlations of residuals and modification indices in the one-factor model. Two items exhibited a relevant residual correlation (r = .10) and high modification index (MI = 79.62): “It is frightening that climate change is causing the destruction of natural areas at such a dramatic rate that they will never be the same again.” and “I am not comforted by the thought that nature can regenerate itself to some extent, because what we have destroyed will never return.”. As these items exclusively formed a factor in the two-factor solution, we attributed the misfit in the one-factor solution to the similar wording of both items. Consequently, we added the correlation between both items to the model, which substantially improved model fit in the one-factor solution, RMSEA = 0.071, 90% CI[0.051, 0.093], CFI = 0.993, TLI = 0.986, χ2 (8, N = 871) = 43.30, p < 0.001. All items of the EGriQ-6 had salient factor loadings (see Table 2) and good internal consistency (α = 0.84).

4.1.3 Eco-Anxiety questionnaire (EAQ-22)

The hypothesized model for the EAQ-22 with the factors habitual ecological worry and negative consequences of eco-anxiety was identified with satisfactory fit, RMSEA = 0.061, 90% CI [0.057, 0.065], CFI = 0.976, TLI = 0.974, χ2 (208, N = 871) = 879.52, p < 0.001. All items had salient loadings on the respective factors (see Table 3). Both subscales showed good to excellent internal consistencies (habitual ecological worry: α = 0.93; negative consequences of eco-anxiety: α = 0.86).

4.2 Potential correlates of the EGuiQ-11, EGriQ-6, and EAQ-22

The EGuiQ-11, the EGriQ-6, as well as the subscales of the EAQ-22 habitual ecological worry and negative consequences of eco-anxiety were significantly and positively correlated (see Table 4). As hypothesized (H1a-H1c), CAS scores were most strongly associated with the negative consequences of eco-anxiety subscale, but were also significantly correlated with habitual ecological worry, eco-guilt, and ecological grief. Similar to previous research and consistent with H2, both climate action intentions and policy support showed moderate to high positive correlations with eco-guilt, ecological grief, and habitual ecological worry, but also with the negative consequences of eco-anxiety subscale. To gain a better understanding of the relationships between all eco-emotions with climate action intention and policy support, we conducted follow-up hierarchical linear regressions on both variables with a stepwise inclusion of eco-guilt, ecological grief, and both eco-anxiety subscales. As shown in Table 5, all steps provided incremental validity to the regression models. Interestingly, eco-guilt and ecological grief did not significantly predict climate action intentions after the inclusion of both eco-anxiety variables. Multicollinearity analyses indicated a considerable collinearity of habitual ecological worry with the other independent variables, VIF (variance inflation factor) = 3.39. The results of the regression analyses may consequently be affected by shared variances of all eco-emotion variables. In conformity with H3, all eco-emotions were positively and significantly correlated with psychological distress (negative consequences of eco-anxiety showing the strongest and ecological grief the weakest associations). Younger participants reported slightly higher levels of habitual ecological worry, negative consequences of eco-anxiety, and eco-guilt, but not ecological grief. Participants that identified as female (compared to male)Footnote 3 indicated significantly higher intensities of eco-guilt (M(SD)female = 23.43(7.47), M(SD)male = 21.17(7.50), t(861) = -4.39, p < 0.001, d = -0.30), ecological grief (M(SD)female = 16.15(3.85), M(SD)male = 14.54(3.85), t(861) = -5.76, p < 0.001, d = -0.42), habitual ecological worry (M(SD)female = 40.00(8.17), M(SD)male = 35.59(9.56), t(861) = -7.28, p < 0.001, d = -0.50), and the negative consequences of eco-anxiety (M(SD)female = 13.73(4.21), M(SD)male = 12.75(4.01), t(861) = -3.41, p < 0.001, d = -0.24).

5 Discussion

5.1 Psychometric properties of the EGuiQ-11, EGriQ-6, and EAQ-22

The main aim of this study was to validate a German version of the EGuiQ-11, EGriQ-6, and EAQ-22 by Ágoston, Urbán, et al. [14]. First, we analyzed the factor structure of all three questionnaires. In line with the original versions of the questionnaires, multiple confirmatory factor analyses revealed an acceptable model fit for the one factor solution of the EGuiQ-11, and the two-factor solution of the EAQ-22 with the subscales habitual ecological worry and negative consequences of eco-anxiety. When accounting for correlations between two items with similar wording, a one factor solution could also be confirmed for the German version of the EGriQ-6. However, a subsequent exploratory factor analysis revealed good model fit for a two-factor solution, but unfavorable factor loadings of two items. Interestingly, Ágoston, Urbán, et al. found a similar pattern in an initial seven item version of the ecological grief questionnaire. These findings may reflect the heterogeneity of ecological grief suggested by previous theoretical models [3]. As discussed by Ágoston, Urbán, et al., the EGriQ-6 is a valid measure for general ecological grief, but future studies may want to include additional items to assess various facets of this emotion. All questionnaires showed good to excellent internal consistencies.

As an indicator of convergent and discriminant validity, we expected CAS scores to be highly correlated with the negative consequences of eco-anxiety subscale of the EAQ-22, but only weakly correlated with the habitual ecological worry subscale. In accordance with H1a, the results revealed a high correlation between climate anxiety and the negative consequences of eco-anxiety (r = .76), which indicates that both scales may measure a clinically relevant facet of eco-anxiety. However, contrary to our expectations (H1b), climate anxiety was also moderately correlated with the habitual ecological worry subscale (r = .51), which was construed as an indicator of practical eco-anxiety [19]. In fact, climate anxiety was also substantially associated with eco-guilt (r = .63) and ecological grief (r = .49), and all three eco-emotions were highly correlated among each other (r > .50). Although all eco-emotions are conceptually related, the magnitude of these associations may be inflated by common factors in all measurements of eco-emotions. For example, all scales may in part also capture pro-environmental attitudes. Accordingly, previous studies found small to moderate correlations of climate anxiety with nature connectedness [54], environmental identity [15], and pro-environmental values [20]. Furthermore, recent studies revealed that individuals who have more knowledge about climate change experience less climate anxiety [55]. In light of these findings, questionnaires on eco-emotions may not exclusively capture the affective responses of individuals, but also additional motivational or cognitive variables. Future studies may compare the scores of the eco-emotion questionnaires with affective responses from experience sampling methods [56] to gain further insight on construct validity.

All eco-emotions were positively correlated with climate action intentions and climate policy support. These findings correspond with previous theoretical and empirical literature on eco-emotions as drivers of climate action and pro-environmental behaviour [1, 9, 18, 20]. However, follow-up regression analyses revealed eco-guilt and ecological grief as non-significant predictors of climate action intentions after including both eco-anxiety subscales. This finding again hints at a potential conceptual overlap between all eco-emotions by measuring motivational factors apart from affective experiences, which may in turn reduce the incremental predictive validity of each eco-emotion. Although the correlational nature of our study does not permit causal interpretations, previous experimental research observed increased pro-environmental behavior after inducing negative eco-emotions [23, 37]. Consequently, the EGuiQ-11, EGriQ-6, and EAQ-22 may be valid measures of the adaptive facets of eco-guilt, ecological grief, and eco-anxiety.

Interestingly, all three eco-emotions showed moderate to high correlations with climate action intentions and climate policy support in our study, but only small associations with pro-environmental behavior in the original study [14]. At least two conceptual differences between both studies may account for this discrepancy. First, the items in this study were focused on climate action in particular whereas the original study addressed pro-environmental behavior in general. Pro-environmental behavior, defined as “behavior that harms the environment as little as possible, or even benefits the environment” [57, p. 309], contains but is not limited to climate action. As previous research identified multiple domains of pro-environmental behavior [58] and individuals behave inconsistently across domains [59], eco-emotions may differently affect certain sets of pro-environmental behavior. Second, this difference may be rooted in the discrepancy between people’s intentions and their actual pro-environmental behaviour [often referred to as green intention behavior gap; 60], as individuals reported specific past behavior habits in the original validation study and abstract future behavior intentions in our study. Subsequent studies should investigate the relationship between self-reported eco-emotions and measures of observed pro-environmental behavior (for example via the Work for Evironmental Protection Task; [61]).

In accordance with previous studies [13, 15, 62], all negative eco-emotions were associated with higher levels of general psychological distress as measured via symptoms of depression and generalized anxiety disorder. Taken together, these findings may suggest that experiences of eco-guilt, ecological grief, and eco-anxiety are potentially stressful and detrimental to overall mental health. However, it seems just as plausible that individuals who suffer, for example, from depressive symptoms may experience stronger affective responses when faced with environmental crises due to emotion regulation deficits [63]. Likewise, general anxiety disorder is characterized by excessive worry about various events [64] and may thus likely expand to environmental concerns. It should be noted that participants in our sample exhibited on average low and nonclinical levels of depression and general anxiety [29]. To further investigate the psychopathological relevance of eco-emotions, future research should apply longitudinal designs and include clinical populations.

Regarding demographic variables, this study was able to replicate the findings of Àgoston, Urbàn, et al. [14]. Younger age was slightly associated with higher levels of eco-guilt and the two factors of eco-anxiety, but not ecological grief. This finding partly coincides with studies [cf. 21] that revealed elevated levels of climate anxiety in younger age groups in Germany [65] and the United States [15]. Although previous research indicated increased concern and awareness regarding climate change in adolescents and young adults [66], we urge caution when interpreting the age effects in our study due to the small correlations and the exclusively adult sample. Also, in line with other studies on eco-emotions [14, 15, 21], participants who identified as female reported slightly higher levels of negative eco-emotions than participants who identified as male. Although these affective differences may reflect differences in pro-environmental attitudes or stereotypes [67] inherent in the eco-emotion questionnaires, clinical psychological research robustly identified gender differences regarding, for example, elevated prevalences for anxiety disorders [68] or depression [69] in individuals identifying as female. Whether the association of gender identity with eco-emotions is a result of attitudinal, stereotypical, or vulnerability related factors requires further research. Again, however, it should be noted that all gender-based differences were only small to medium in effect sizes.

5.2 Limitations and future research

Similar to the original validation study [14], the findings of our study are based on a convenience sample and the generalizability to the general population is limited. Although we observed a heterogeneity regarding socioeconomic status in our sample, participants with high education levels and income were overrepresented. However, previous research found only small negative effects of education level on eco-emotions [14] and no effect of income on climate anxiety [22]. Furthermore, individuals who identified as female were slightly overrepresented in our sample and indicated higher levels of eco-emotions. Therefore, our results may overestimate the extent of these experiences in the general population. Future studies should not only investigate all three questionnaires in quota samples, but also focus on subpopulations that may experience high levels of eco-emotions, e.g., people who were exposed to extreme weather events [70].

Applying the eco-emotion questionnaire in subpopulations that are differently affect by the consequences of ecological crises would also improve the validation of the scales in terms of known-group validity. Along these lines, further validation steps should include assessments of test–retest reliability via longitudinal designs as well as indicators of incremental and predictive validity by, e.g., including additional measures of pro-environmentalism. The inclusion of further outcome variables seems especially relevant regarding the items used in this study to measure climate action intention and policy support. Although both scales exhibited acceptable internal consistency and the climate action intention items have been applied in previous studies [21, 28], they lack extensive validation. Furthermore, the climate policy support items were tailored to reflect relevant policies in Germany, but this degree of specificity comes at the expense of cross-societal generalizability. Consequently, more general and extensively validated measurements (e.g., [71, 72]) should be included in future studies to further validate the three eco-emotion questionnaires.

The scope of the validated questionnaires was limited to the assessment of eco-guilt, ecological grief, and eco-anxiety. However, emotional reactions to environmental issues are manifold [6]. For example, individuals frequently report anger and frustration regarding environmental crises, which in turn was positively associated with increased personal and collective pro-environmental behavior [4]. Previous research also investigated positive emotions concerning climate change, e.g., hope. Accordingly, constructive hope, in contrast to hope based on denial, was positively related to environmental engagement [5]. The increasing scientific interest in the investigation of various eco-emotions should be accompanied by psychometrically sound research instruments. Therefore, future research may want to expand the focus of the eco-emotion questionnaires of Ágoston, Urbán, et al. [14] by including additional emotional reactions. As a more comprehensive assessment of multiple eco-emotions may cause fatigue effects in participants, shorter versions of the scales should be constructed and validated.

6 Conclusion

This study contributes to the rapidly expanding field of affective environmental research by offering thoroughly translated and validated German versions of questionnaires on eco-guilt, ecological grief, and eco-anxiety. The investigated research instruments seem suitable to fill the methodological gap that is especially salient in the assessment of eco-guilt and ecological grief. Beyond a replication of the structures of the three questionnaires, we linked the investigated eco-emotions to increased climate action intentions and climate policy support, but also elevated (yet mostly nonclinical) levels of psychological distress. Thus, an adequate measurement of emotional reactions to climate change and other environmental crises can help predict and navigate the adaptive and maladaptive consequences of eco-emotions.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Open Science Framework at osf.io/skehr/.

Notes

Subsequent correlational analyses were performed on a subset of n = 859, after excluding participants with missing values on any questionnaire.

We did not regard a significant χ2-test for goodness of fit as a sufficient indicator of bad model fit due to the oversensitivity of this index in large samples.

As only eight participants identified as diverse, they were not included in the t-tests.

References

Shipley NJ, van Riper CJ. Pride and guilt predict pro-environmental behavior: a meta-analysis of correlational and experimental evidence. J Environ Psychol. 2022;79:11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101753.

Clayton S. Climate anxiety: psychological responses to climate change. J Anxiety Disord. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102263.

Cunsolo A, Ellis NR. Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nat Clim Chang. 2018;8(4):275–81. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0092-2.

Stanley SK, Hogg TL, Leviston Z, Walker I. From anger to action: differential impacts of eco-anxiety, eco-depression, and eco-anger on climate action and wellbeing. J Clim Change Health. 2021;1:100003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joclim.2021.100003.

Ojala M. Hope in the face of climate change: associations with environmental engagement and student perceptions of teachers’ emotion communication style and future orientation. J Environ Educ. 2015;46(3):133–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2015.1021662.

Pihkala P. Toward a taxonomy of climate emotions. Front Clim. 2022;3:22. https://doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2021.738154.

Poortinga W, Demski C, Steentjes K. Generational differences in climate-related beliefs, risk perceptions and emotions in the UK. Communications Earth Environment. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00870-x.

Poortinga W, Whitmarsh L, Steg L, Bohm G, Fisher S. Climate change perceptions and their individual-level determinants: a cross-European analysis. Global EnvironChange. 2019;55:25–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.01.007.

Brosch T. Affect and emotions as drivers of climate change perception and action: a review. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2021;42:15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2021.02.001.

Frijda NH, Kuipers P, Terschure E. Relations among emotion, appraisal, and emotional action readiness. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;57(2):212–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.2.212.

Kenrick DT, Griskevicius V, Neuberg SL, Schaller M. Renovating the pyramid of needs: contemporary extensions built upon ancient foundations. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2010;5(3):292–314. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610369469.

van Valkengoed AM, Steg L. Meta-analyses of factors motivating climate change adaptation behaviour. Nat Clim Change. 2019;9(2):158. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0371-y.

Ogunbode CA, Pallesen S, Bohm G, Doran R, Bhullar N, Aquino S, et al. Negative emotions about climate change are related to insomnia symptoms and mental health: Cross-sectional evidence from 25 countries. Curr Psychol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01385-4.

Ágoston C, Urbán R, Nagy B, Csaba B, Köváry Z, Kovács K, et al. The psychological consequences of the ecological crisis: Three new questionnaires to assess eco-anxiety, eco-guilt, and ecological grief. Clim Risk Manag. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2022.100441.

Clayton S, Karazsia BT. Development and validation of a measure of climate change anxiety. J Environ Psychol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101434.

Hogg TL, Stanley SK, O’Brien LV, Wilson MS, Watsford CR. The Hogg eco-anxiety scale: development and validation of a multidimensional scale. Global Environ Change. 2021;71:10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102391.

Stewart AE. Psychometric properties of the climate change worry scale. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(2):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020494.

Comtesse H, Ertl V, Hengst SMC, Rosner R, Smid GE. Ecological grief as a response to environmental change: a mental health risk or functional response? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(2):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020734.

Kurth C, Pihkala P. Eco-anxiety: What it is and why it matters. Front Psychol. 2022;13:13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.981814.

Verplanken B, Marks E, Dobromir AI. On the nature of eco-anxiety: how constructive or unconstructive is habitual worry about global warming? J Environ Psychol. 2020;72:11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101528.

Wullenkord MC, Troger J, Hamann KRS, Loy LS, Reese G. Anxiety and climate change: a validation of the climate anxiety Scale in a German-speaking quota sample and an investigation of psychological correlates. Clim Change. 2021;168(3–4):23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-021-03234-6.

Whitmarsh L, Player L, Jiongco A, James M, Williams M, Marks E, et al. Climate anxiety: what predicts it and how is it related to climate action? J Environ Psychol. 2022;83:10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101866.

Mallett RK. Eco-Guilt Motivates Eco-Friendly Behavior. Ecopsychology. 2012;4:223–31. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2012.0031.

Hickman C, Marks E, Pihkala P, Clayton S, Lewandowski RE, Mayall EE, et al. Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: a global survey. Lancet Planetary Health. 2021;5(12):E863–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00278-3.

Stroebe MS, Hansson RO, Stroebe W, Schut H. Handbook of bereavement research: Consequences, coping, and care. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2001.

Pihkala P. Anxiety and the ecological crisis: an analysis of eco-anxiety and climate anxiety. Sustainability. 2020;12(19):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12197836.

Clayton S, Manning CM, Krygsman K, Speiser M. Mental health and our changing climate: impacts, implications, and guidance. Washington: American Psychological Association, and ecoAmerica; 2017.

Wullenkord MC, Heidbreder LM, Reese G. Reactions to environmental changes: place attachment predicts interest in earth observation data. Front Psychol. 2020;11:15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01442.

Lowe B, Wahl I, Rose M, Spitzer C, Glaesmer H, Wingenfeld K, et al. A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2010;122(1–2):86–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.019.

Clark LA, Watson D. Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. Psychol Assess. 1995;7(3):309–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.7.3.309.

van Valkengoed AM, Abrahamse W, Steg L. To select effective interventions for pro-environmental behaviour change, we need to consider determinants of behaviour. Nat Hum Behav. 2022;6(11):1482–92. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01473-w.

Rees JH, Klug S, Bamberg S. Guilty conscience: motivating pro-environmental behavior by inducing negative moral emotions. Clim Change. 2015;130(3):439–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-014-1278-x.

Adams I, Hurst K, Sintov ND. Experienced guilt, but not pride, mediates the effect of feedback on pro-environmental behavior. J Environ Psychol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101476.

Bouman T, Verschoor M, Albers CJ, Bohm G, Fisher SD, Poortinga W, et al. When worry about climate change leads to climate action: how values, worry and personal responsibility relate to various climate actions. Global Environ Change. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102061.

Goldberg MH, Gustafson A, Ballew MT, Rosenthal SA, Leiserowitz A. Identifying the most important predictors of support for climate policy in the United States. Behaviour Public Policy. 2021;5(4):480–502. https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2020.39.

Gustafson A, Ballew MT, Goldberg MH, Cutler MJ, Rosenthal SA, Leiserowitz A. Personal stories can shift climate change beliefs and risk perceptions: the mediating role of emotion. Commun Rep. 2020;33(3):121–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/08934215.2020.1799049.

Schwartz D, Loewenstein G. The chill of the moment: emotions and proenvironmental behavior. J Public Policy Mark. 2017;36(2):255–68. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.16.132.

Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Wittchen HU. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21(3):169–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1359.

Ágoston C, Csaba B, Nagy B, Köváry Z, Dúll A, Rácz J, et al. Identifying types of eco-anxiety, eco-guilt, eco-grief, and eco-coping in a climate-sensitive population: a qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(4):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042461.

Bonanno GA, Kaltman S. The varieties of grief experience. Clin Psychol Rev. 2001;21(5):705–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(00)00062-3.

Leiner D. SoSci Survey (Version 3.2.25) [Computer software]. 2021. Available at https://www.soscisurvey.de.

Leiner D. Our research’s breadth lives on convenience samples A case study of the online respondent pool “SoSci Panel.” Stud Commun Media. 2016;5:367–96. https://doi.org/10.5771/2192-4007-2016-4-367.

Kyriazos T. Applied psychometrics: sample size and sample power considerations in factor analysis (EFA, CFA) and SEM in general. Psychology. 2018;09:2207–30. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2018.98126.

Sahin MD. Effect of item order on certain psychometric properties: a demonstration on a cyberloafing scale. Front Psychol. 2021;12: 590545. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.590545.

Leiner D. Too fast, too straight, too weird: non-reactive indicators for meaningless data in internet surveys. Survey Res Methods. 2019. https://doi.org/10.18148/srm/2019.v13i3.7403.

Bundesregierung. Klimaschutzprogramm 2030 der Bundesregierung zur Umsetzung des Klimaschutzplans 2050. Berlin: Bundestag; 2019. p. 133.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Lowe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):613–21. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613.

Corp I. IBM SPSS statistics for windows (Version 27.0). Armonk: IBM Corp; 2020.

Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 8th ed. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 1998.

Hooper D, Coughlan J, Mullen M. Structural Equation Modeling: Guidelines for Determining Model Fit. Electron J Bus Res Methods. 2008;6:53–60.

Alavi M, Visentin DC, Thapa DK, Hunt GE, Watson R, Cleary M. Chi-square for model fit in confirmatory factor analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2020;76(9):2209–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14399.

Beauducel A, Herzberg PY. On the performance of maximum likelihood versus means and variance adjusted weighted least squares estimation in CFA. Struct Equ Modeling-A Multidiscip J. 2006;13(2):186–203. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1302_2.

Raubenheimer J. An item selection procedure to maximise scale reliability and validity. South Afr J Indust Psychol. 2004. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v30i4.168.

Curll SL, Stanley SK, Brown PM, O’Brien LV. Nature connectedness in the climate change context: implications for climate action and mental health. Transl Issues Psychol Sci. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000329.

Zacher H, Rudolph CW. Environmental knowledge is inversely associated with climate change anxiety. Clim Change. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-023-03518-z.

Kuppens P, Oravecz Z, Tuerlinckx F. Feelings change: accounting for individual differences in the temporal dynamics of affect. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;99(6):1042–60. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020962.

Steg L, Vlek C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: an integrative review and research agenda. J Environ Psychol. 2009;29(3):309–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2008.10.004.

Larson LR, Stedman RC, Cooper CB, Decker DJ. Understanding the multi-dimensional structure of pro-environmental behavior. J Environ Psychol. 2015;43:112–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.06.004.

Gatersleben B, Steg L, Vlek C. Measurement and determinants of environmentally significant consumer behavior. Environ Behav. 2002;34(3):335–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916502034003004.

ElHaffar G, Durif F, Dube L. Towards closing the attitude-intention-behavior gap in green consumption: a narrative review of the literature and an overview of future research directions. J Clean Prod. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122556.

Lange F, Dewitte S. The work for environmental protection task: a consequential web-based procedure for studying pro-environmental behavior. Behav Res Methods. 2022;54(1):133–45. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-021-01617-2.

Searle K, Gow K. Do concerns about climate change lead to distress? Int J Clim Change Strat Manag. 2010;2(4):362–79. https://doi.org/10.1108/17568691011089891.

Joormann J, Gotlib IH. Emotion regulation in depression: relation to cognitive inhibition. Cogn Emot. 2010;24(2):281–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930903407948.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Virginia: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Hajek A, König HH. Climate anxiety in Germany. Public Health. 2022;212:89–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2022.09.007.

Corner A, Roberts O, Chiari S, Völler S, Mayrhuber ES, Mandl S, et al. How do young people engage with climate change? The role of knowledge, values, message framing, and trusted communicators. Wiley Interdiscip Rev-Clim Chang. 2015;6(5):523–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.353.

Brough AR, Wilkie JEB, Ma JJ, Isaac MS, Gal D. Is eco-friendly unmanly? The green-feminine stereotype and its effect on sustainable consumption. J Consum Res. 2016;43(4):567–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucw044.

McLean CP, Asnaani A, Litz BT, Hofmann SG. Gender differences in anxiety disorders: prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45(8):1027–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.03.006.

Piccinelli M, Wilkinson G. Gender differences in depression—critical review. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:486–92. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.177.6.486.

Ogunbode CA, Bohm G, Capstick SB, Demski C, Spence A, Tausch N. The resilience paradox: flooding experience, coping and climate change mitigation intentions. Clim Policy. 2019;19(6):703–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2018.1560242.

Kaiser FG, Wilson M. Assessing people’s general ecological behavior: a cross-cultural measure. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2000;30(5):952–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02505.x.

Kaiser FG, Gerdes R, König F. Supporting and expressing support for environmental policies. J Environ Psychol. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2023.101997.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Open access funding was granted by the publication fund of the Johannes Gutenberg-University Mainz. PZ received intramural funding from the Johannes Gutenberg-University Mainz.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by PZ. The first draft of the manuscript was written by PZ and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the ethics committee of the Johannes Gutenberg-University Mainz (2023-JGU-psychEK-S020).

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zeier, P., Wessa, M. Measuring eco-emotions: a German version of questionnaires on eco-guilt, ecological grief, and eco-anxiety. Discov Sustain 5, 29 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00209-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00209-2