Abstract

This study examines the mediating effect of job stress and the moderating effect of job autonomy on the relationship between work-to-family conflict (WFC) and job satisfaction and organizational commitment. It uses cross-sectional data from 1062 prison officers sampled from 31 prison establishments in Ghana. The results of structural equation modelling (SEM) analysis showed that WFC was negatively associated with job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Job stress significantly mediated the influence of WFC on job satisfaction and organizational commitment. The negative influence of WFC on job satisfaction and organizational commitment was less for prison officers with higher levels of job autonomy than for those with lower levels of autonomy. These findings suggest the need for correctional organizations to adopt family-friendly measures that facilitate officers’ ability to integrate their work and family responsibilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prison officers are critically important to the success or failure of correctional organizations, as they embody the prison regime. Consequently, their attitudes and behaviours have received a great deal of empirical attention, with much of the research focussed on job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Armstrong & Griffin, 2004; Jiang et al., 2017). These two factors have been linked with many occupational outcomes in the corrections literature. For example, officers who are satisfied with and committed to their jobs have been found to demonstrate high levels of job performance and organizational citizenship behaviour, increased support for offender rehabilitation, and lower absenteeism, turnover intent, and actual turnover (e.g. Lambert et al., 2009, 2013a, 2013b; Liu et al., 2017; Matz et al., 2013; Stinchcomb & Leip, 2013).

In Ghana, a recent surge in prison officer misconduct involving abuse of power, corruption and dealing in narcotics has prioritized the issues of officer satisfaction and commitment to the ideals of prison work and the organization, as well as the quality of the officers themselves.Footnote 1 These developments have been costly to the reputation of the Ghana Prisons Service (GPS). The situation resonates with Haarr’s (1997) policing research based on interviews and field observations that “patrol officers with low levels of organizational commitment tended to engage in work avoidance and manipulation, deviant activities against the organization, and accepted informal rewards”. Due to the costly nature of prison officer malpractices on prison organizations, penologists and correctional managers have become more interested in discovering the antecedents of prison officers’ job satisfaction and commitment in order to optimize them.

Because of the impact of job satisfaction and commitment on a wide range of important correctional outcomes, a great deal of research has focussed on the correlates of job satisfaction and organizational commitment. This line of research has linked various aspects of prison work, such as role conflict, role ambiguity, the dangerousness of the job, job stress, and work climate in general to job attitudes among prison officers (Lambert & Paoline, 2008; e.g. Lambert et al., 2010, 2016; Stinchcomb & Leip, 2013). However, the impact of prison work on an officer’s family life and how this influences their job attitude has received less attention. The stressful nature of working in the prison environment suggests that officers are increasingly exposed to excessive demands at work, thereby making it difficult to meet demands in other important life domains such as the family (Triplett et al., 1999). This phenomenon, referred to as ‘work–family conflict’, has received widespread empirical attention in the organizational psychology and management literature (e.g. Byron, 2005; Frone et al., 1992; Michel et al., 2011; Shaffer et al., 2011), but its recognition in the corrections literature is recent and limited (Crawley, 2002; Jiang et al., 2017; Lambert et al., 2013a, 2013b; Liu et al., 2017).

Research on work–family conflict in the corrections literature suggests that increased levels of work–family conflict undermine job satisfaction and organizational commitment among correctional staff (e.g. Armstrong et al., 2015; Hsu, 2011; Lambert et al., 2002). While extant research has contributed to our understanding of the deleterious impact of work–family conflict in the corrections literature, there is a dearth of research into why work–family conflict exerts a negative influence on prison officers. In addition, research has rarely examined moderators of the relationship between officers’ work–family conflict and job outcomes. Moreover, most of the studies on work–family conflict and its impact on occupational outcomes in the corrections literature have been conducted in mainly Western industrialized countries. Only a few studies have addressed work–family conflict in non-Western contexts, with the African context conspicuously missing from this line of inquiry. The present study attempts to address these gaps in previous research by examining the mediating influence of job stress and the moderating influence of job autonomy on the relationship of work–family conflict with job satisfaction and organizational commitment among Ghanaian prison officers.

The study contributes to the literature in three ways. First, it employs a stress perspective to explain the link between work–family conflict and job attitudes within the prison context. In this way, the study conceptualizes work–family conflict as a stressor impacting on officers’ job attitudes through its influence on job stress. Work–family conflict is recognized as a significant source of stress, and stress has been associated with various job outcomes. Yet the role of job stress in linking work–family experiences to job outcomes has not been directly examined before in the prison context. Drawing on Hobfoll’s (1989) ‘conservation of resources’ theory and the source attribution model of stress (Grandey et al., 2005), we argue that the experience of work–family conflict results in the depletion of salient resources among prison officers. Depletion of resources associated with work–family conflict heightens stress, leading to decreased satisfaction and commitment to the job.

Second, as noted earlier, the corrections literature is silent on moderators of the influence of work–family conflict on job outcomes. Findings suggest that the impact of stressors upon strain depends on the availability of salient resources (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). In this regard, we propose that job autonomy, an important job resource, may mitigate the impact of work–family conflict on prison officers’ satisfaction with and commitment to their job. Although the moderating role of job autonomy has received widespread empirical attention in the organizational psychology literature, little research has been devoted to understanding how job autonomy may buffer the impact of work–family conflict in the correctional context. Our study not only contributes to understanding the boundary conditions for the relationship between work–family conflict and job attitudes; it also generates knowledge about how to mitigate the outcomes of work–family conflict among prison officers.

Third, by conducting this research in an African context, the study complements efforts to broaden the focus of research on work–family conflict and occupational outcomes from a non-western perspective. As noted by various criminological scholars, research from the global south is necessary for establishing whether “new ideas or policy innovations uncovered in one society may have applicability in others” (LaFree, 2007: 16) and for confirming whether concepts and generalizations developed in one country are true of all societies (Bendix, 1963).

Cross-cultural research on the work–family interface suggests that cultural values underpin the experience of work–family conflict and its impact on employees’ job attitudes (Annor & Burchell, 2018; Lu et al., 2010; Ollier-Malaterre et al., 2013). Consequently, the impact of work–family conflict on prison officers’ satisfaction with and commitment to the job may be different in African countries than the impact in the West. In Ghana, the strict hierarchical command-and-control management structure adopted by the GPS for communication and leadership implies that prison officers have less autonomy in executing their work. Additionally, excessive overcrowding (currently at 46.5% over capacity), coupled with staff shortages, means that prison officers in Ghana typically work long hours beyond the required eight-hour shift period with mandatory unpaid overtime, so as to ensure 24-h security. Although most Ghanaian officers have significant family responsibilities owing to societal emphasis on large family sizes, extended family relations, and marriage and procreation in Ghanaian culture, formal family-friendly policies are limited to the statutory 12-week paid maternity leave (Akoensi, 2017; Annor, 2014). The absence of paternity leave, making fathers unable to contribute meaningfully to childcare and household responsibilities, further perpetuates traditional gender values. Consequently, the work–family experiences of prison officers in Ghana may differ from those of their counterparts in the West. Thus, understanding how experiences of work–family conflict impact on job attitudes of prison officers has implications for enhancing the performance and effectiveness of correctional systems in Africa.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

Work and family represent distinct but strongly interconnected life domains, such that demands from one domain can spill over into the other domain. Greenhaus and Beutell (1985, p. 77) defined work–family conflict as “a form of interrole conflict in which the role pressures from the work and family domains are mutually incompatible in some respect”. Thus, work–family conflict occurs when demands in the work domain make it more difficult to meet responsibilities in the family domain and vice versa. Greenhaus and Beutell (1985) identified three major forms of work–family conflict: time-, strain- and behaviour-based conflict. Time-based conflict occurs when time demands associated with one role (e.g. work) make it difficult to participate in another role (e.g. family). Strain-based conflict occurs when stress resulting from participation in one role makes it difficult to meet demands in another role. Behaviour-based conflict occurs when behavioural expectations associated with one role are incompatible with those associated with another role.

Current research recognizes work–family conflict as bidirectional (e.g. Michel et al., 2011; Shaffer et al., 2011). Thus, work–family conflict may originate from the work domain (i.e. work-to-family conflict) or from the family domain (i.e. family-to-work conflict). Work-to-family conflict (WFC) occurs when participation in the work role makes it difficult to participate in the family role, whereas family-to-work conflict (FWC) occurs when participation in the family role makes it difficult to fulfil responsibilities in the work role. In the present study we focus on work-to-family conflict for two reasons. First, research in the organizational psychology literature indicates that WFC is more prevalent than FWC (e.g. Michel et al., 2011). In Ghana, Akoensi (2017) noted that the nature of a prison officer’s job makes work–family conflict unidirectional, with conflict originating mainly from the work domain to the family domain because the Prison Service makes total claims on officers’ loyalty to the organization at the expense of their family commitments. Secondly, WFC and FWC have been found to have different antecedents and consequences, with antecedents and outcomes of WFC located mainly in the work domain, whereas antecedents and outcomes of FWC are mainly family-related (Michel et al., 2011; Shockly & Singla, 2011). Consequently, the directions of work–family conflict can be studied independently.

As stated above, the conservation of resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 1989, 2002) provides the theoretical traction for the conceptual relationships examined in this study. The COR theory attempts to explain individuals’ response to stress as an interplay between gains and losses of resources, defined as those “objects, personal characteristics, conditions or energies that are valued in their own right or that are valued because they act as conduits to the achievement or protection of valued resources” (Hobfoll, 2001, p. 339). The central tenet of the COR theory is that individuals strive to retain, protect, and build resources, and that psychological stress represents individuals’ reaction to the actual and perceived loss of resources or lack of gain following investment of resources (Hobfoll, 1989). A key assumption of COR theory is that individuals expend resources to deal with stressful circumstances, so that continued exposure to stressors will increase the susceptibility to further resource depletion, a situation described as a ‘loss spiral’. The COR theory also assumes that individuals invest resources in order to prevent future resource loss and to avoid negative outcomes. Consequently, the COR theory proposes that access to resources reduces individuals’ vulnerability to stress and its associated negative outcomes.

On the basis of COR theory, we conceptualize work–family conflict as a stressor which impacts negatively on employees’ job attitudes. In contrast, resources such as job autonomy can buffer the negative impact of work–family conflict on job outcomes (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). Thus, we apply the COR theory in the present study to explain the linkages of WFC with job satisfaction and organizational commitment, as well as the moderating role of job autonomy in the relationships. The conceptual model for the study is presented in Fig. 1.

WFC and Prison Officer Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment

Work–family conflict has been linked to many work-related outcomes in both the correctional and non-correctional literatures. Salient among these outcomes are employees’ attitudes to their work, and specifically job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Although there is no consensus over the definition of ‘job satisfaction’, common to various definitions of the construct is the notion that job satisfaction emanates from employees’ subjective evaluation of actual job outcomes in relation to expected job outcomes. For example, according to Locke (1976, p. 1300), job satisfaction represents ‘‘a pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experiences’’, while Spector (1997) defined job satisfaction as the extent to which employees like or dislike their job.

Organizational commitment, another important job attitude, reflects “a desire, a need, and/or an obligation to maintain membership in the organization” (Meyer & Allen, 1991, p. 62). Meyer and Allen (1991) distinguished between three dimensions of organizational commitment: affective, normative, and continuance commitment. Affective commitment refers to the extent to which employees are emotionally attached to, identify with, and are involved in that organization; continuance commitment refers to employees’ desire to remain with an organization because of investments they have made in it; and normative commitment refers to the extent to which employees feel obliged to remain within an organization (Meyer & Allen, 1991). The present study focuses on the affective dimension, as it represents the predominant approach to conceptualizing organizational commitment (Jiang et al., 2017). In Ghana, officers’ positions are permanent and pensionable, an incentive for them to remain in post until retirement, irrespective of any cognitive and emotional job evaluations. Thus, among officers in this context, normative and continuance commitment may be less likely to change in response to adverse work experiences.

On the influence of WFC on employee job attitudes, Grandey et al. (2005) argue that individual attitudes towards the job are influenced by the extent to which it presents as a threat to other self-relevant goals—that is, to roles considered salient to individuals’ identity. When these roles are threatened by negative job experiences, employees are likely to evaluate the source of the threat (i.e. the job) negatively (Grandey et al., 2005). It has also been argued, on the basis of COR theory, that the experience of WFC depletes resources such as time and energy that could be devoted to other life domains such as the family (Grandey & Cropanzano, 1999). Thus, work–family conflict presents as a threat to employees constructing a stable role-related self-identity (Frone et al., 1992), who consequently attribute blame to the source of the conflict, resulting in negative attitudes towards that domain. Since WFC denotes that the conflict originates from the work domain, it follows that high levels of WFC would be associated with negative job attitudes. Accordingly, several studies outside the corrections literature have found that WFC is negatively related to job satisfaction and organizational commitment (e.g. Brough et al., 2005; Bruck et al., 2002; Grandey et al., 2005; Wayne et al., 2004).

We argue that when work schedules or the demands of the prison work make participation in family activities difficult or impossible, officers might be resentful towards their job and experience low job satisfaction. Most of the studies on the influence of work–family conflict on job satisfaction and organizational commitment in the correctional context have focussed on correctional staff, a term that embraces both custody and non-custody staff and not specifically on prison officers as a distinct group with unique job demands and characteristics, who work 24-h shifts to secure an unwilling population and at the same time assist in their rehabilitation (e.g. Armstrong et al., 2015; Hogan et al., 2006; Lambert et al., 2006). Together, these studies suggest that high levels of WFC are associated with decreased job satisfaction and organizational commitment in correctional facilities. For example, based on 272 staff in a Midwestern (United States) maximum-security prison, Hogan et al. (2006) reported a negative relationship between WFC conflict and staff organizational commitment. In a similar study among 160 correctional staff in a private medium-security prison in the Midwestern United States, Lambert et al. (2002) found that WFC was a significant negative predictor of job satisfaction but that FWC was not significantly related to job satisfaction. Drawing on the same dataset as Lambert et al. (2002), Lambert et al. (2006) found that job satisfaction negatively predicted strain- and behaviour-based WFC, whereas organizational commitment was negatively predicted by time- and behaviour-based WFC. Armstrong et al. (2015) also showed that strain-based and behaviour-based WFC negatively predicted job satisfaction among correctional staff in the US. On the basis of COR theory and empirical research we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 1a

Work-to-family conflict will be negatively related to job satisfaction.

Hypothesis 1b

Work-to-family conflict will be negatively related to organizational commitment.

Job Stress as a Mediator Between WFC and Prison Officer Job Attitudes

‘Job stress’ is generally defined in the literature as an employee’s feelings of job-related hardness, tension, anxiety, frustration, worry, emotional exhaustion and distress (Armstrong & Griffin, 2004; Lambert, 2004). Job stress has received considerable attention in the corrections literature as a potential consequence associated with work–family conflict. As noted by Lambert and his colleagues “if work is causing conflict at home, that conflict can become a new source of job stress” (Lambert et al., 2006, p. 378). However, the role of job stress in linking work–family conflict to prison officers’ job attitudes has yet to be examined. Drawing on the COR theory, it is argued that work–family conflict represents a source of stress because “resources are lost in the process of juggling work and family roles” (Grandey & Cropanzano, 1999, p. 352). Increased stress resulting from the potential or actual loss of resources may result in negative state of being, in the form of reduced commitment, dissatisfaction or psychological strain (Grandey & Cropanzano, 1999). We therefore expect that WFC would heighten job stress among prison officers, which would in turn result in decreased satisfaction with and commitment to the job.

In line with our argument, a number of studies in the corrections literature point to a positive and direct relationship between WFC and job stress. For example, Triplett et al. (1999) found that work-home conflict was a significant contributor to work-related stress among correctional officers. Lambert et al. (2006) found that strain-based WFC positively predicted job stress. Liu et al. (2017) found among 322 staff in two Chinese prisons that strain-based conflict and behaviour-based work-to-family conflict were positively related to job stress. The direct link between job stress and job attitudes is also well established in the correctional literature. Several studies in the correctional literature have demonstrated that job stress is inversely related to job satisfaction and organizational commitment (e.g. Griffin et al., 2010; Lambert & Paoline, 2008; Lambert et al., 2004, 2013a; Mahfood et al., 2013; Moon & Jonson, 2012). As WFC relates to job stress, which in turn relates to job satisfaction and organizational commitment, we expect WFC to be indirectly related to these job attitudes. Accordingly, a study by Singh and Nayak (2015) among police officers in India found that job stress significantly mediated the relationship between work–family conflict and job satisfaction. Based on the COR theory and extant research, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 2a

Job stress will mediate the relationship between WFC and job satisfaction.

Hypothesis 2b

Job stress will mediate the relationship between WFC and organizational commitment.

Job Autonomy as a Moderator Between WFC and Prison Officer Job Attitudes

Job autonomy is defined as “the degree to which the job provides substantial freedom, independence, and discretion to the individual in scheduling their work and in determining the procedures to be used in carrying it out” (Hackman & Oldham, 1976, p. 258). Previous studies in the corrections literature have focussed mainly on the direct influence of job autonomy on work stressors such as work–family conflict. Given that prison officers typically have low autonomy, it has been argued that increased job autonomy would enable them to manage demands from the work and family domains, thereby minimizing the occurrence of work–family conflict. However, beyond its main effect, job autonomy may have a buffering effect by reducing the impact of work–family conflict on job outcomes.

Our expectation regarding the buffering effect of job autonomy among correctional officers is predicated on the COR theory’s assumption that “people must invest resources in order to protect against resource loss, recover from losses, and gain resources” (Hobfoll, 2011, p. 117). Hobfoll (2011) argued that individuals with large resource reservoirs are less vulnerable to resource loss in the face of stressful situations such as work–family conflict. Job autonomy represents a form of job resource located at the task level (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007), which affords employees greater responsibility and flexibility in organizing duties associated with work when they are faced with conflict between work and family (Billing et al., 2014; Grzywacz & Marks, 2000). Thus, prison officers with greater control in their line of work would be better able to cope with work–family conflict and subsequently experience lower levels of distress and resentment. A number of studies outside the correctional literature have provided empirical support for the buffering effect of job autonomy on the influence of work–family conflict on employee well-being and job outcomes such as job satisfaction and organizational commitment (e.g. Bakker & Demerouti, 2007; Bakker et al., 2005; Billing et al., 2014; Yucel, 2019). Extending these studies to the correctional context, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 3a

Job autonomy will moderate the relationship between WFC and job satisfaction such that it reduces the strength of the relationship.

Hypothesis 3b

Job autonomy will moderate the relationship between WFC and organizational commitment such that it reduces the strength of the relationship.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

The data for the study come from a convenience sample of prison officers based at 31 (out of 43) prisons in Ghana. The selected facilities encompassed all prison categories from low-security to medium-security prisons. Most of the surveys were distributed at meetings with officers, where the first author was given the opportunity to introduce the aims of the study. For reasons of security, not all officers attended such meetings. Surveys were distributed in brown envelopes to officers at their various posts including workshops, wings or dormitories, guard posts, gates, kitchens and general offices. Participants were informed of the voluntary nature of their participation, assured of the confidentiality of their responses and that they had the right to decline participation in the study at any point, although they were encouraged not to do so.

Out of 1490 questionnaires distributed, 1117 were returned, resulting in a response rate of 74.9%. Data from 55 respondents were deleted due to incomplete responses, leaving 1062 usable questionnaires. The high response rate is mainly attributed to the meetings held for this research that took place in 26 of the 31 prisons, where they generated an average response rate of 81.2%. Table 1 displays the demographic characteristics of the sample.

Measures

Work-to-Family Conflict

WFC was measured with six items, five of which were adapted from Netemeyeri et al. (1996). Sample items include “the demands from my work as a prison officer interfere with my home and family life) and “I often miss important family or social activities, e.g. spending time with the family, outdoorings, funerals, etc. because of my job”. Each item was measured on a five-point Likert scale, from ‘strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘strongly agree’ (5). The scale proved to be highly reliable, with a Cronbach alpha of 0.86.

Job Stress

Job stress was measured with four items adapted from Cullen et al. (1985) because of its alignment with prison officers’ own conceptualization of job stress as work pressure, anxiety and tension, frustration and anger, and physical exhaustion associated with prison work in Ghana (Akoensi, 2014). Some job stress statements include “A lot of the time my job makes me frustrated or angry”, and “When I’m at work, I often feel tense, anxious and uptight”. Each item was measured on a five-point Likert scale from ‘strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘strongly agree’ (5). When computed, this four-fold measure of job stress yielded a Cronbach alpha of 0.76.

Job Satisfaction

A global measure of job satisfaction, rather than a measure of the specific aspects of officers’ work, was adopted for this study. Four items adapted from Brayfield and Rothe (1951), and later adopted in correctional contexts (e.g. Lambert & Paoline, 2008), measured job satisfaction in this study. Each item was measured on a five-point Likert scale from ‘strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘strongly agree’ (5). The computed scale also proved to be reliable, with a Cronbach alpha of 0.73.

Organizational Commitment

The study used an attitudinal measure of organizational commitment focussing on employees’ emotional and cognitive bonds. Four items adapted from Mowday et al. (1982) were used to measure organizational commitment. Sample items include “I find that my personal values and that of the Ghana Prisons Service are similar” and “I am proud to tell others that I work for the Ghana Prisons Service”. The items were measured on five-point Likert scales, from ‘strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘strongly agree’ (5). High scores therefore reflect a commitment and vice versa. When the scale was computed, a Cronbach alpha of 0.74 was obtained.

Job Autonomy

Job autonomy was measured with five items capturing employees’ ability to influence tasks and decisions in their work area. The items were adapted from House (1981) (e.g. “I have little control over the tasks that I perform”). Each item was measured on a five-point Likert scale from ‘strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘strongly agree’ (5). High scores reflect high levels of job autonomy and vice versa. When the scale was computed, a Cronbach alpha of 0.75 was obtained.

Control Variables

Several demographic variables were included in the study to control for potential confounds. These included gender (0 = male; 1 = female), age, level of education, rank, and tenure.

Results

Validity Issues

We conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using AMOS 21.0 to test whether the latent variables were distinct from each other. We estimated a measurement model with five latent factors representing the constructs in the study: WFC, job stress, job autonomy, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment. Model fit was assessed using the chi-square test, the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). As presented in Table 3, results of the CFA suggest that the hypothesized five-factor model fitted the data well (χ2 (214) = 525.73, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.96, SRMR = 0.04, RMSEA = 0.04). These results indicate that the five latent variables in the study were distinct. The standardized factor loadings for items measuring the constructs ranged from 0.48 to 0.88 (see Table 2).

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Means, standard deviations and correlations among the study variables are presented in Table 3. The descriptive and correlations for the latent variables were computed based on imputed factor scores from measurement model in the CFA. WFC was positively correlated with job stress (r = 0.63, p < 0.001) and negatively correlated with job satisfaction (r = –0.33, p < 0.001) and organizational commitment (r = – 0.30, p < 0.001), which supported Hypotheses 1a and 1b. Job stress was negatively correlated with job satisfaction (r = – 0.55, p < 0.001) and organizational commitment (r = – 0.46, p < 0.001). Furthermore, job autonomy was negatively correlated with WFC (r = – 0.48, p < 0.001) but positively correlated with job satisfaction (r = 0.35, p < 0.001) and organizational commitment (r = 0.36, p < 0.001). Among the demographic variables, gender, tenure and level of education had significant correlations with job stress, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment.

Mediation Analyses

The hypothesized mediation relationships were tested with structural equation modelling analyses using AMOS 21.0.Footnote 2 Although we included all demographic variables that were significantly correlated with job stress, job satisfaction and organizational commitment, only tenure and gender were left in the final modelling; the others made no statistically significantly contributions. First, we tested the hypothesized model (i.e. Model 1) in which the path coefficients among WFC, job stress, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment were freely estimated. The results (see Table 3) showed that the hypothesized model fitted the data well. (χ2 (154) = 358.72, p < 0.01; SRMR = 0.03; TLI = 0.96; CFI = 97; RMSEA = 0.04). The hypothesized model was then compared to alternative structural models to determine the best-fitting model using the chi-square difference test. First we compared the hypothesized model with a direct model (i.e. Model 2), in which paths coefficients from WFC to job stress and from job stress to organizational commitment and job satisfaction were constrained to zero. The results showed that Model 1 demonstrated a significantly better fit than Model 2 (Δχ2 (3) = 305.65, p < 0.001). Finally, Model 1 was compared with an indirect model (i.e. Model 3), in which path coefficients from WFC to job satisfaction and organizational commitment were constrained to zero. The results showed no statistically significant difference between the fit of the two models (Δχ2 (2) = 3.33, p > 0.05). Consequently, the hypothesized model was retained for subsequent analyses.

In the hypothesized model, WFC is positively related to job stress (β = 0.54, p < 0.001), while job stress is negatively related to job satisfaction (β = –0.41, p < 0.001) and organizational commitment (β = –0.31, p < 0.001). However, the direct relationships of WFC with job satisfaction (β = –0.06, p > 0.05) and organizational commitment (β = –0.09, p > 0.05) were not statistically significant, although the correlation analyses indicated statistically significant bivariate relationships. These results suggest that the relationships between WFC and both job satisfaction and organizational commitment were mediated by job stress.

We probed the mediating role of job stress in the relationships of WFC with job satisfaction and organizational commitment, using bootstrapping procedures suggested by Shrout and Bolger (2002). Specifically, we created 5000 bootstrap samples to estimate the confidence intervals for the indirect effects of WFC on job satisfaction and organizational commitment with the bias-corrected percentile method. The results indicate that the indirect effect of WFC on job satisfaction via job stress was statistically significant (β = – 0.22, p < 0.001), with a 99% confidence interval ranging from – 0.32 to – 0.13. The indirect effect of WFC on organizational commitment via job stress was also statistically significant (β = – 0.17, p < 0.001), with a 99% confidence interval ranging from – 0.27 to – 0.08. These results indicate that job stress mediated the relationships of WFC with job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Therefore, Hypotheses 2a and 2b were supported.Footnote 3 (Fig. 2).

We also conducted multi-group SEM analysis to examine potential gender differences in the findings obtained with the full sample. First, we tested the hypothesized model separately for males and females. Next, we specified two simultaneous between-group models to test whether the strengths and directions of the relationships were invariant across gender. In the first between-group model, which served as a baseline, all factor loadings were constrained to be equal across gender, while all structural parameters of the model were freely estimated for males and females. In the second between-group model, both factor loadings and structural parameters were constrained to be equal across gender. A significant increase in the chi-square for the model with equality constraints on factor loadings and path coefficients implies that the assumption of invariance would not be tenable (Byrne, 2010). The results of the multi-group SEM analyses are presented in Table 4. The within-group analysis indicated that the hypothesized model fitted the data well for males (χ2 (124) = 251.25, p < 0.001; SRMR = 0.03; RMSEA = 0.04; CFI = 0.97; TLI = 0.96) and females (χ2 (124) = 213.72, p < 0.001; SRMR = 0.04; RMSEA = 0.05; CFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.95). The results for between-group analyses indicated that there were no significant differences between males and females with regards to the parameter estimates for the hypothesized relationships (Δχ2 (5) = 10.14, p > 0.05). These results suggest that the hypothesized model was invariant across gender. Thus, gender did not significantly moderate any of the hypothesized relationships.

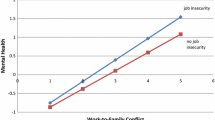

Moderation Analyses

Hypotheses 3a and 3b, which postulate that job autonomy would buffer the relationships of WFC with job satisfaction and organizational commitment, were tested using the PROCESS macro (version 3.5) for SPSS (Hayes, 2018). Both WFC and job autonomy were mean-centred prior to the analysis to avoid multicollinearity. Gender, tenure, rank, and job stress were included in the model as covariates. As shown in Table 3, the interactions between WFC and job autonomy were significantly related to job satisfaction (b = 0.18, p < 0.001) and organizational commitment (b = 0.16, p < 0.001). We explored the nature of the interactions graphically, using values 1 standard deviations (hereafter, SD) below the mean and 1 SD above the mean on both WFC and job autonomy. The plots for the interaction effects are shown in Figs. 3 and 4 respectively. As shown in Fig. 3, the relationship between WFC and job satisfaction is weaker when job autonomy is high than when job autonomy is low. Similarly, the relationship between WFC and organizational commitment is weaker when job autonomy is high than when job autonomy is low. These results suggest moderation effects of job autonomy on the relationships of WFC with job satisfaction and organizational commitment, in support of Hypotheses 3a and 3b (Table 5).

Discussion

Previous studies suggest that work–family conflict has significant negative effect on job attitudes among correctional officers. However, apart from being largely Western-focussed, these studies have failed to examine mechanisms by which work–family conflict impacts on officers’ job attitudes and the role of job autonomy in buffering the negative effects of work–family conflict on job attitudes. Drawing on data obtained from prison officers in Ghana, the present study empirically examined the mediating role of job stress in the relationships between WFC and both job satisfaction and organizational commitment. The study also examined the role of job autonomy in moderating the relationships between WFC and both job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

As expected, WFC conflict was found to be important in shaping prison officers’ satisfaction with and commitment to the job. Specifically, prison officers who experienced higher levels of WFC were found to report lower levels of job satisfaction and organizational commitment. This finding is consistent with previous studies suggesting that high levels of WFC are associated with negative job attitudes among correctional staff (e.g. Armstrong et al., 2015; Hogan et al., 2006; Lambert et al., 2002, 2006). Given that most previous studies on work–family conflict have been conducted in Western countries, the present study’s findings suggest that the negative impact of work–family conflict on correctional staff job attitudes also has applicability in non-Western contexts, particularly in the sub-Saharan African context. This study also extends an initial qualitative effort by Akoensi (2017), which documented experiences of work–family conflict among prison officers in Ghana, by demonstrating the adverse impact of work–family conflict on job attitudes among prison officers. As members of a collectivist society, Ghanaians tend to place greater emphasis on maintaining harmonious family relationships, which typically include the extended family. A person’s status in the family is judged not only in terms of their ability to provide for their family financially and materially, but also in terms of their level of participation in important family activities such as funerals and their commitment to the general well-being of extended family members. Consequently, as noted by Frone et al. (1992), prison officers whose job frequently interferes with their family life may perceive their job as a threat to constructing a good family identity and thus evaluate their job negatively.

Our findings further suggest that the negative relationship between WFC and prison officers’ job attitudes is indirect, being mediated by job stress. Specifically, high levels of WFC were found to be associated with high job stress, which was in turn related to reduced levels of job satisfaction and organizational commitment. This finding extends previous research on the link between work–family conflict and job outcomes in the correctional literature. While previous studies have shown that WFC is negatively related to job stress, job satisfaction and organizational commitment, and that job stress is negatively related to these job attitudes, the indirect relationship between WFC and job attitudes has not previously been examined, and this study sought to address this lacuna in the penal literature. Our study demonstrates that job stress provides a psychological mechanism through which WFC negatively impacts prison officers’ satisfaction with, and commitment to, the job. Our finding concurs with Sing and Nayak’s (2015) study among police officials in India, which reported that stress mediated the relationship between work–family conflict and job satisfaction. Our finding is also in line with those of Mansour and Mahonna (2017), which suggested that job stress mediated the relationship between work–family conflict and perception of service quality among hotel employees. The indirect link between WFC and job attitudes through job stress aligns with the ‘loss spiral’ assumption of COR theory, which contends that exposure to stressors depletes resources, making fewer resources available for mitigating subsequent exposure to stress (Hobfoll, 1989). Thus, prison officers experiencing high WFC feel overwhelmed by their inability to meet both nuclear- and extended- family demands, as personal resources (e.g. time and emotional energy) are lost in the process of dealing with these interferences in this African prison context. The ensuing stress prompts prison officers to become more resentful towards the job—the source of the conflict—and thereby to evaluate their job negatively, in terms of low job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Hennessy, 2008).

The results of the moderated regression show that job autonomy significantly moderated the relationships between WFC and job satisfaction and organizational commitment. The negative relationship between WFC, job satisfaction and organizational commitment was weaker for prison officers who reported having high job autonomy than for those who reported low job autonomy. Thus, not only does job autonomy minimize the experience of work-related stressors, particularly among high-ranking prison officers, as documented in previous studies (e.g. Lambert et al., 2012), but it also helps to mitigate the negative impact of work–family conflict on job attitudes. As a job resource, job autonomy enhances officers’ sense of control, thereby decreasing the likelihood of negatively interpreting conflict between work and family roles. As noted earlier, the paramilitary management structure of the GPS means that discretionary power is concentrated at the top management level with minimal to no discretionary powers left for low-ranking frontline officers to decide how and when specific tasks are to be completed or which criteria should be adopted in assessing their work performance, although frontline officers’ discretion in the enforcement of prison rules is inevitable (see Liebling, 2004). This finding indicates that allowing officers some discretion over their work roles, especially in scheduling, may enhance officers’ positive emotional states by communicating to them “they are valued, respected, and trusted” (Lambert et al., 2012, p. 14). However, feelings of frustration and helplessness are inevitable when officers have no autonomy, and this undermines their ability to handle work stressors. Although autonomy has been found to be more concentrated among superior officers’ ranks than among subordinate officers’ ranks, the moderating effect of job autonomy on the relationship between WFC and job attitudes remained even after accounting for rank.

Limitations and Directions for Further Research

This study is not without limitations. First, it examined work–family conflict as a composite variable without delineating the different components of conflict. The work–family literature suggests that work–family conflict may be time-based, strain-based or behaviour-based. Although different components may have differential effects on job stress and job attitudes (e.g. Liu et al., 2017), the study did not distinguish between them. We suggest that future research might employ a more comprehensive measure of work–family conflict to address the various dimensions of WFC.

Second, our study adopted a cross-sectional design with single-source data based on self-report. This makes it difficult to derive causal inferences from our results and to rule out common-method bias entirely. For instance, the fact that participants had to report on their experiences of work–family conflict, job stress, and work attitudes may inflate the relationship among these variables, although results from the CFA confirmed the uniqueness of the constructs. Studies adopting longitudinal approaches with data from multiple sources would help to establish the temporal order of relationships between work–family conflict and job attitudes and also to minimize concerns about common-method bias.

Practical Implications

Correctional systems thrive on committed and satisfied staff. Our finding that work–family conflict undermines employee job satisfaction and organizational commitment, albeit indirectly, underscores the need for correctional organization managers to develop and implement measures that would help prison officers successfully juggle work and family demands, as previous research in Ghana shows that employment demands stretched officers’ resources to the extent that participation in family activities was impossible. Time- (e.g. overtime and lack of autonomy) and strain- (e.g. accommodation and deployment) based demands were formidable and impacted prison officers to an extent resulting in job stress (Akoensi, 2017). The literature on work–family conflict offers a variety of opportunities for improving employees’ ability to combine work and family responsibilities. It is not far-fetched to suggest that correctional managers should receive training to recognize the significant family demands on prison officers and to accommodate flexible scheduling in their supervision and job performance appraisals. Correctional institutions may also benefit from workshops designed to equip prison officers and managers with strategies to deal with competing demands from work and family domains.

Another implication of our findings is that initiatives designed to mitigate the impact of work–family conflict on job stress would be concomitantly beneficial in enhancing job satisfaction and organizational commitment among prison officers. An initiative that seems particularly relevant in this regard is the provision of stress-management workshops for prison officers (Netemeyer et al., 2005). Such workshops could provide a forum where officers discuss family-related concerns with superiors and colleagues and receive practical suggestions from workshop facilitators for managing multiple roles.

A further implication highlights the importance of job autonomy as resource for mitigating the impact of work–family conflict. Job autonomy affords employees the opportunity to determine “the pace, sequence, and methods for accomplishing tasks without major organizational constraints and restrictions” (Volmer et al., 2012, p. 462). Although the paramilitary organizational structure of the GPS places significant constraints on the extent to which prison officers are able to exercise discretion, our findings highlight the need to develop organizational interventions such as the re-design of jobs to allow prison officers an opportunity to control certain aspects of their work-life without compromising prison security, and to give them opportunities to contribute to decision-making affecting their work. A move towards team-based work where officers are able to contribute to team decision-making may be an attractive and viable option to promote officers’ sense of autonomy or control at the very minimum.

Overall, the study has shown that work–family conflict constitutes a significant problem among prison officers in Ghana, as it undermines their satisfaction with and commitment to the job. Our study suggests that job stress constitutes the pathway along which work–family conflict exerts its negative influence on job attitudes. Moreover, our findings suggest that correctional organizations may benefit from rethinking the extent of direction and control that prison officers have in carrying out their work.

Notes

An officer sentenced to 13 years for dealing in narcotics (https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/Prison-officer-slapped-with-13-year-jail-sentence-for-narcotics-648320); another interdicted for escorting prisoners to purchase alcohol and cigarettes at a pub (https://www.graphic.com.gh/news/general-news/ghana-prisons-to-take-action-against-alcohol-drinking-officer.html) and finally, a male officer assaulting and injuring a female referee at a local female football league game was reported by the BBC (https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/football/47870661. These are just a few cases of officer misconduct reported recently in both the electronic and print media.

Given that the data were collected from 31 prisons, we explored the possibility of clustering in the data and whether it was necessary to conduct multilevel analysis. The results of our initial analysis involving a random intercept model showed that the amount of variance in the outcome variables (job satisfaction and organizational commitment) attributable to the group (i.e. the prison in which officers are based) was minimal (< .3%). This obviated the need for multilevel analysis. Hence, data from officers across the different prisons were pooled for individual-level analysis.

We further tested whether the hypothesized model was invariant across different types of prison (i.e. low-security and medium-security prisons). Results from multi-group SEM showed that the model fitted the data well for both types of prison, and no significant difference was found in any of the hypothesized path estimates.

References

Akoensi, T. D. (2014). A tougher beat? The work, stress and well-being of prison officers in Ghana. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation. University of Cambridge, UK.

Akoensi, T. D. (2017). ‘In this job, you cannot have time for family’: Work–family conflict among prison officers in Ghana. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895817694676

Annor, F. (2014). Managing work and family demands: The perspectives of employed parents in Ghana. In Z. Mokomane (Ed.), Work-family interface in Sub-Saharan Africa (pp. 17–36). Springer International Publishing.

Annor, F., & Burchell, B. (2018). A cross-national comparative study of work demands/support, work-to-family conflict and job outcomes: Ghana versus the United Kingdom. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 18(1), 53–72.

Armstrong, G. S., Atkin-Plunk, C. A., & Wells, J. (2015). The relationship between work-family conflict, correctional officer job stress, and job satisfaction. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 42(10), 1066–1082.

Armstrong, G. S., & Griffin, M. L. (2004). Does the job matter? Comparing correlates of stress among treatment and correctional staff in prisons. Journal of Criminal Justice, 32(6), 577–592.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328.

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Euwema, M. C. (2005). Job resources buffer the impact of job demands on burnout. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10, 170–180.

Bendix, R. (1963). Concepts and generalizations in comparative sociological studies. American Sociological Review, 28, 532–539.

Billing, T. K., Bhagat, R. S., Babakus, E., Krishnan, B., Ford, D. L., Srivastava, B. N., Rajadhyaksha, U., Shin, M., Kuo, B., Kwantes, C., Setiadi, B., & Nasurdin, A. M. (2014). Work-family conflict and organisationally valued outcomes: The moderating role of decision latitude in five national contexts. Applied Psychology: an International Review, 63(1), 62–95.

Brayfield, A., & Rothe, H. (1951). An index of job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 35(5), 307–311.

Brough, P., O’Driscoll, M. P., & Kalliath, T. J. (2005). The ability of ‘family friendly’ organizational resources to predict work-family conflict and job and family satisfaction. Stress and Health, 21(4), 223–234.

Bruck, C. S., Allen, T. D., & Spector, P. E. (2002). The relation between work-family conflict and job satisfaction: A finer-grained analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 60(3), 336–353.

Byrne, B. (2010). Structural equation modeling using AMOS. In Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Byron, K. (2005). A meta-analytic review of work-family conflict and its antecedents. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67(2), 169–198.

Cullen, F., Link, B., Wolfe, N., et al. (1985). The social dimensions of correctional officer stress. Justice Quarterly, 2(4), 505–533.

Crawley, E. M. (2002). Bringing it all back home? The impact of prison officers’ work on their families. Probation Journal, 49(4), 277–286.

Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Cooper, M. (1992). Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: Testing a model of the work-family interface. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77(1), 65–78.

Grandey, A. A., Cordeiro, B. L., & Crouter, A. C. (2005). A longitudinal and multi-source test of the work-family conflict and job satisfaction relationship. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78(3), 305–323.

Grandey, A. A., & Cropanzano, R. (1999). The conservation of resources model applied to work–family conflict and strain. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54(1999), 350–370.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10(1), 76–88.

Griffin, M. L., Hogan, N. L., Lambert, E. G., Tucker-Gail, K. A., & Baker, D. N. (2010). Job involvement, job stress, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment and the burnout of correctional staff. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 37(2), 239–255.

Grzywacz, J. G., & Marks, N. F. F. (2000). Reconceptualizing the work–family interface: An ecological perspective on the correlates of positive and negative spillover between work and family. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 111–126.

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1976). Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 16(2), 250–279.

Haarr, R. N. (1997). “They’re making a bad name for the department”: Exploring the link between organizational commitment and police occupational deviance in a police patrol bureau. Policing: International Journal of Police Strategies and Management, 20(4), 768–812.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). . Guilford Press.

Hennessy, D. A. (2008). The impact of commuter stress on workplace aggression. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 38(9), 2315–2335.

Hobfoll, S. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6(4), 307–324.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2011). Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84(1), 116–122.

Hogan, N. L., Lambert, E. G., Jenkins, M., & Wambold, S. (2006). The impact of occupational stressors on correctional staff organizational commitment: A preliminary study. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 22(1), 44–62.

House, J. S. (1981). Work stress and social support. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Hsu, Y. R. (2011). Work-family conflict and job satisfaction in stressful working environments. International Journal of Manpower, 32(2), 233–248.

Jiang, S., Lambert, E. G., Liu, J., Kelley, T. M., & Zhang, J. (2017). Effects of work environment variables on Chinese prison staff organizational commitment. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 51(2), 275–292.

LaFree, G. (2007). Expanding criminology’s domain: The American Society of Criminology 2006 Presidential Address. Criminology, 45, 1–31.

Lambert, E. G. (2004). The impact of job characteristics on correctional staff members. The Prison Journal, 84(2), 208–227.

Lambert, E. G., Altheimer, I., & Hogan, N. L. (2010). An exploratory examination of a gendered model of the effects of role stressors. Women & Criminal Justice, 20(3), 193–217.

Lambert, E. G., Hogan, N. L., & Barton, S. M. (2002). The impact of work-family conflict on correctional staff job satisfaction: An exploratory study. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 27(1), 35–52.

Lambert, E. G., Hogan, N. L., & Barton, S. M. (2004). The nature of work-family conflict among correctional staff: An exploratory examination. Criminal Justice Review, 29(1), 145–172.

Lambert, E. G., Hogan, N. L., Barton, S. M., & Elechi, O. O. (2009). The impact of job stress, job involvement, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment on correctional staff support for rehabilitation and punishment. Criminal Justice Studies, 22(2), 109–122.

Lambert, E. G., Hogan, N. L., Camp, S. D., & Ventura, L. A. (2006). The impact of work-family conflict on correctional staff: A preliminary study. Criminology and Criminal Justice, 6(4), 371–387.

Lambert, E. G., Hogan, N. L., Dial, K. C., Jiang, S., & Khondaker, M. I. (2012). Is the job burning me out? An exploratory test of the job characteristics model on the emotional burnout of prison staff. Prison Journal, 92(1), 3–23.

Lambert, E. G., Hogan, N. L., & Paoline, E. A. (2016). Differences in the predictors of job stress and job satisfaction for Black and White Jail Staff. Corrections, 1(1), 1–19.

Lambert, E. G., Kelley, T., & Hogan, N. L. (2013a). The association of occupational stressors with different forms of organizational commitment among correctional staff. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 38(3), 480–501.

Lambert, E. G., Kelley, T., & Hogan, N. L. (2013b). Work-family conflict and organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Crime and Justice, 36(3), 398–417.

Lambert, E. G., & Paoline, E. A. (2008). The influence of individual, job, and organizational characteristics on correctional staff job stress, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment. Criminal Justice Review, 33(4), 541–564.

Liebling A., assisted by H. Arnold. (2004). Prisons and their moral performance. Oxford University Press.

Liu, J., Lambert, E. G., Jiang, S., & Zhang, J. (2017). A research note on the association between work–family conflict and job stress among Chinese prison staff. Psychology, Crime and Law, 23(7), 633–646.

Locke, E. A. (1976). The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In M. D. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 1297–1343). Chicago, IL: Rand McNally.

Lu, L., Cooper, C., Kao, S. F., Chang, T.-T., Allen, T. D., Lapierre, L. M., O’Driscoll, M. P., Poelmans, S. A. Y., Sanchez, J. I., & Spector, P. E. (2010). Cross-cultural differences on work-to-family conflict and role satisfaction: A Taiwanese-British Comparison. Human Resource Management, 49(1), 67–85.

Mahfood, V. W., Pollock, W., & Longmire, D. (2013). Leave it at the gate: Job stress and satisfaction in correctional staff. Criminal Justice Studies, 26(3), 308–325.

Mansour, S., & Mohanna, D. (2017). Mediating role of job stress between work-family conflict, work-leisure conflict, and employees’ perception of service quality in the hotel industry in France. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism., 17(2), 154–174.

Matz, A. K., Wells, J. B., Minor, K. I., & Angel, E. (2013). Predictors of turnover intention among staff in juvenile correctional facilities. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 11(2), 115–131.

Meyer, J., & Allen, N. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1(1), 61–89.

Michel, J., Kotrba, L., Mitchelson, J. K., Clark, M. A., & Baltes, B. B. (2011). Antecedents of work–family conflict: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32, 689–725.

Moon, M. M., & Jonson, C. L. (2012). The influence of occupational strain on organizational commitment among police: A general strain theory approach. Journal of Criminal Justice, 40(3), 249–258.

Mowday, R., Porter, L., & Steers, R. (1982). Employee-organization linkages: They psychology of commitment, absenteeism and turnover. Academic Press.

Netemeyer, R. G., Maxham, J. G., & Pullig, C. (2005). Conflicts in the work-family interface: Links to job stress, customer service employee performance, and customer purchase intent. Journal of Marketing, 69(2), 130–143.

Ollier-Malaterre, A., Valcour, M., Den Dulk, L., & Kossek, E. E. (2013). Theorizing national context to develop comparative work–life research: A review and research agenda. European Management Journal, 31, 433–447.

Shaffer, M. A., Joplin, J. R. W., & Hsu, Y.-S. (2011). Expanding the boundaries of work–family research: A review and agenda for future research. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 11(2), 221–268.

Shrout, P., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422–445.

Singh, R., & Nayak, J. K. (2015). Mediating role of stress between work-family conflict and job satisfaction among the police officials: Moderating role of social support. Policing: an International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 38(4), 738–753.

Spector, P. E. (1997). Job satisfaction. Sage.

Stinchcomb, J. B., & Leip, L. A. (2013). Expanding the literature on job satisfaction in corrections. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 40(11), 1209–1227.

Triplett, R., Mullings, J. L., & Scarborough, K. E. (1999). Examining the effect of work-home conflict on work-related stress among correctional officers. Journal of Criminal Justice, 27(4), 371–385.

Volmer, J., Spurk, D., & Niessen, C. (2012). Leader-member exchange (LMX), job autonomy, and creative work involvement. Leadership Quarterly, 23(3), 456–465.

Wayne, J. H., Musisca, N., & Fleeson, W. (2004). Considering the role of personality in the work-family experience: Relationships of the big five to work-family conflict and facilitation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64(1), 108–130.

Yucel, D. (2019). Job autonomy and schedule flexibility as moderators of the relationship between work-family conflict and work-related outcomes. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 14(5), 1393–1410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9659-3

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix 1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Akoensi, T.D., Annor, F. Work–Family Conflict and Job Outcomes Among Prison Officers in Ghana: A Test of Mediation and Moderation Processes. Int Criminol 1, 135–149 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43576-021-00020-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43576-021-00020-3