Abstract

The study of the ethnicity of authors, illustrators, and characters in children’s literature is important for understanding the ethnic normativity messages that children receive through books. However, ethnic representation in children’s books has rarely been studied in Asian countries. The present study examined the ethnic representation of authors, illustrators, and characters of books for young children that (1) won awards, or (2) were in the annual sales ranks in one of the most popular online book stores in China from 2011 to 2018. In total, 75 books and 1858 human characters were coded. Results suggest a dominant representation of East Asian authors, East Asian illustrators, and White characters. Male characters were overrepresented (especially East Asian males). East Asian characters (especially females) were more prominent according to some indicators, whereas White characters (especially males) were more prominent according to the other indicators. Gender differences in physical features in East Asian characters were found in terms of eye shapes and straight hair. Light skin color was overrepresented in East Asian characters (especially females). The results indicate overrepresentation of White authors, illustrators, and characters as compared to population statistics, as well as the preference for White skin color in East Asian characters in illustrations. The results suggest a form of current postcolonial globalization influencing Chinese children’s literature, and can help to explain potential early origins of preference for people and culture mostly identified as White (or Western) in China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Shared reading by parents and children encourages children to engage in literature with pleasure. Being represented in books by means of characters of the same gender and/or ethnicity contributes to identification with characters and higher reading motivation of children (Hughes-Hassell et al. 2009). In addition, illustrations of human characters in books may transmit physical feature preferences to children, impacting children’s body image development and self-evaluation (Thompson and Heinberg 1999). White dominance in characters and authors in books for young children has been widely found in countries with majority White populations (e.g., de Bruijn et al. 2020; Koss 2015; Koss et al. 2017), suggesting fewer identification opportunities for underrepresented ethnic groups, as well as potential White-normative messages about physical appearance (Russell et al. 1992). Given the highly developed globalized market and a history of White dominance in many parts of the world in (post-)colonial times, similar patterns might be present in children’s books in other parts of the world where the majority of the population is not White. Considering the (semi)colonial history of China, its current globalized economy, and its Westernized beauty standards (Stohry et al. 2021; Yu 2021), the study of the ethnicity of authors, illustrators, and characters in children’s books in contemporary China is important for our understanding of ethnic normativity messages children receive through books in a different context. The present study aims to examine (1) ethnic representation of authors, illustrators, and characters in books for young children (6 years or younger) in China and (2) the physical features of human East Asian characters in these books.

Books portraying characters are created by different authors and illustrators. Authors and illustrators are usually better able to represent the uniqueness and universality of the images of their own cultural group in books (Bista 2012; Youngs 2015). Previous studies have indicated that 88 to 96% of books for young children in Canada, the Netherlands, and the United States were written by White authors, and 83 to 94% books were illustrated by White illustrators (de Bruijn et al. 2020; Dionne 2014; Eisenberg 2002; Garner and Parker 2018; Koss 2015; Koss et al. 2017; Kurz 2012). Clearly, we see White dominance in terms of authors and illustrators among children’s books. This means that authentic information about White culture are more likely to be seen by readers. In contrast, the readers from ethnically underrepresented groups have fewer opportunities to read accurate and positive messages about their ethnic group to contribute to their cultural understanding and self-esteem (Hughes-Hassell and Cox 2010), and there are fewer opportunities for White children to learn about diverse heritages and cultures. In addition, children from ethnically underrepresented groups might benefit from books written by authors and illustrators who share their ethnicity, because children may see them as role models (Hughes-Hassell et al. 2009).

Within the works of all authors, it is also important to look at the representation of characters in books for young children, because identification between a reader and a character in books is “an imaginative process through which an audience member assumes the identity, goals, and perspective of a character” (Cohen 2001, p. 261). As may be expected, young readers in North Atlantic countries predominantly see White characters (75–95%, de Bruijn et al. 2020; Dionne 2014; Hughes-Hassell and Cox 2010; Koss 2015). In other words, White children, compared to children of other ethnicities, have more opportunities to identify with a White character, and such identification can make them feel more connected to the character’s experiences and emotions (Slater and Rouner 2002; Witmer and Singer 1998). Identification with characters increases with similarity between characters and readers in terms of for example ethnicity, gender, and age (Chen et al. 2016). Further, characters with whom the young reader can identify also make children believe that the children themselves can be written about in stories, and this may increase their reading motivation, and ultimately reading achievement (Hughes-Hassell et al. 2009).

The illustrations of human characters and their physical features in books are also salient to young children. Sociocultural theory emphasizes that the preferred physical features shown in media influence children’s physical feature preferences and body image development (Rice et al. 2016; Thompson and Heinberg 1999). This is because physical feature preferences are transmitted through a variety of sociocultural channels (e.g., toys, printed media, books), that are then internalized by the audience. Preferences for specific ethnic physical features start early, as shown for example by the fact that White Barbie dolls are preferred over Black ones by children 3–7 years of age of various ethnic backgrounds (Gibson et al. 2015). Dittmar et al. (2006) adopted picture books with images of different dolls as body-related stimuli and their findings supported a direct impact of (skinny hour-glass proportioned) images of Barbie dolls as aspirational role models for girls, therefore negatively influencing 5- to 7-years-olds’ body image development and self-evaluation. In the same way, the illustrations of White dominant characters in books may transmit potential White-normative messages about physical appearance to young children.

Although identification with authors, illustrators, and characters from their own ethnic group is important for all children, ethnic representation in children’s books has been studied predominantly in the U.S. Studies on the ethnic representation of authors, illustrators, and characters in books for young children in China or other East Asian countries are lacking. However, books for young children play an increasingly important role in many children’s lives in East Asian countries. Studies show that 18 to 20% Chinese parents read books to their children every day, and 54–58% Chinese families with children 0–6 years have shared reading time 3–4 times per week (Ji 2012; Li et al. 2018). In addition, children’s books occupy approximately one quarter of China’s book market, and the growth rate of book sales for children’s books outnumbered the average growth rates in the book market (Beijing OpenBook 2018). If books represent society, Chinese authors, illustrators, and characters would be expected to dominate Chinese children’s books given the Chinese-dominant demographic context in mainland China (non-Chinese population < 0.06%; NBS 2020a). However, books imported from abroad and translated into Chinese in fact dominate the children’s book market in China (almost 80% of sales; Yang 2012). The impact of such a high percentage of imported books in China’s market on ethnic representation in books for young children in China has not yet been studied.

Many researchers have indicated that White (Western) product popularity and White-normative messages about beauty ideals are prevalent in China and other postcolonial countries due to globalization and postcolonial mechanisms (Goon and Craven 2003; Stohry et al. 2021). Globalization involves growing cross-border trade in products, books and information, and the development of a globalized market. Postcolonialism can be defined as the effect of colonization on the colonized people and their culture after a certain period of high imperialism and colonial occupation (Drew 1999). More specifically, China was defeated by Britain in the Opium Wars (1840–1842) which forced opening to Euro-American powers (and ideology). In the following ca. 100 years, China gradually transformed into a semi-colony under Western military coercion (Lan 2016). The colonial history provided a foundation for the prevalence of “Whiteness” and “White supremacy” in China (Stohry et al. 2021), as illustrated by the observation that Chinese people commonly consider White people and Western culture as “civilized” and “superior” in contemporary China (Liu and Croucher 2022; Yu 2021). Current postcolonial globalization influences are seen in things like the popularity of Caucasian and Eurasian models, celebrities, and Whitening products (Goon and Craven 2003). Similarly, the books written and illustrated by White people may be regarded as more civilized cultural products by Chinese buyers, and those imported books may therefore be more popular in China’s children books’ market.

When it comes to the illustrations of human characters and their physical features, Chinese or East Asian characters depicted in children’s books may have White physical features because of the White beauty ideals. In many Asian countries, including China, White skin color preference is common (Stohry et al. 2021; Yu et al. 2021). This is a reflection of widespread colorism in East Asian countries, which refers to prejudicial and preferential treatment of people solely based on skin tones, with lighter skin evaluated more favorable than dark skin (the term colorism believed to be first coined by Alice Walker in her 1983 book, in Yu 2021). For example, advertisement for skin-related products in magazines in India, Japan, Korea, and Hong Kong commonly show White as representing good skin (Li et al. 2008). TV commercials and print ads in China promote similar esthetic standards of White being more beautiful and indicating higher social status (Mak 2007), thereby spreading a global standard of White beauty ideals in non-White countries. In addition, with regard to facial feature preferences, East Asian faces evaluated as attractive by Asians do not have an epicanthal fold (a skin fold of the upper eyelid covering the inner corner of the eye), and therefore have a less steep slant of the opening between the eye lids than average East Asian faces (Rhee et al. 2012). Considering the early emergence of physical feature preferences in childhood (Gibson et al. 2015; Qian et al. 2016), books for young children with illustrations may work as an important catalyst for the development of physical feature preferences and body image development among Chinese children.

The main aim of the present study is to examine ethnic representation in popular books for young children published in China. They are as follows: (a) What is ethnicity of the authors and illustrators? Is ethnicity of the authors and illustrators associated with ethnicity of the characters in books? (b) What is ethnicity of the characters? Is ethnicity of the characters (in total and per gender) associated with different indicators of roles and prominence? (c) How prevalent are White physical features in East Asian characters in illustrations (i.e., eyes, skin tone, hair color, and hair style)? Are physical features in East Asian characters in illustrations different for male versus female characters? The result will shed light on East Asian and White representation of ethnic features in books for young children in contemporary China, and can serve as a stepping stone to a better understanding of the potential early origins of the preference for White (Western) products and figures in contemporary China.

Method

Sampling

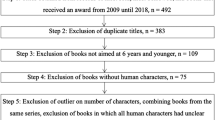

The potential exposure to picture books by Chinese children was the most important criterion in book selection. The first step was to collect the titles of all the children’s books published in mainland China that (1) won an award, or (2) appeared in the sales ranks of children’s books in one of the most popular online bookstores (www.dangdang.com) from 2011 until 2018 (n = 214; see Fig. 1). Awards included in the book selection process were the National Outstanding Children’s Literature Award, China Children’s Books list, Annual Ranking of Original Chinese Picture Books, Feng Zikai Chinese Children’s Picture Book Award, and Chen Bochui International Children’s Literature Award. From the sales ranks reported by the Dangdang online bookstore, the top 10 in the annual ranks for children’s books were selected. If a book was part of a series, only the first book in the list of each series was selected, as some series consisted of up to 100 books.

The next step was to exclude duplications (n = 185). The third step was to exclude books not aimed at children 6 years or younger (n = 138). Age information of the target readers was based on the printed information in books (if available), the target age groups classified by awards (if available), or the book introduction at the Dangdang online bookstore. All books that included at least 0–6 years in the age range of the target audience were included. Specifically, 60% of all sample books (n = 45) were specifically targeted at children under 6 years of age, and 40% (n = 30) were targeted at children both under and over 6 years. The fourth step was to remove the books without human figures (n = 87). During the coding, we removed another 12 books aiming at making handicrafts, containing only photos, or including only human characters coded as having an unclear ethnic appearance (e.g., characters are illustrated in blue). In the end, 75 books for young children were included in the final list to be analyzed (for a list of these books, see online Appendix A), of which 21 were part of a series. Most of the books were story books (89%). The other books were encyclopedia for young children (e.g., introduction of Chinese solar terms; 7%), and poetry or song books (4%).

Procedure

Coding of the books was based on an adapted version of the coding manual used by de Bruijn et al. (2020) (for an overview of coded variables, see online Appendix B). General information about the book was coded, including the year of publication (the first edition of the book), publisher, number of pages, number of pictures, and the storyline. The ethnicity and gender of the authors and illustrators were coded, with adapted categories of ethnicity: (1) East Asian, (2) White, (3) other, and (4) unknown. This information was collected based on the introduction in books, personal webpages, or other websites. The following aspects of all human character illustrations in the book were coded: character’s name, explicit mention of ethnicity or nationality, ethnic appearance, gender (i.e., male, female, unclear), age group (i.e., child, teenager, adult, elderly, unclear), role (i.e., protagonist, secondary, background characters), representation on the cover, and the number of pages and pictures that shows the character.

Ethnic appearance categories were (1) East Asian, (2) White, (3) other, and (4) unclear. Each character was evaluated based on the illustrations throughout the whole book when a character was shown more than once. An East Asian appearance was defined as eyes with epicanthal folds (high frequency in East Asians), and/or tawny beige skin color (neither extremely White nor extremely dark), and ethnic characteristics such as black and straight hair (e.g., a character having eyes with epicanthal folds, tawny beige skin color, sometimes even White skin color, were coded as East Asian). Characters having eyes without epicanthal folds, but showing all the other criteria of typical East Asian physical appearance, i.e., not extreme White skin color, black and straight hair, brown or black eyes, were also coded as East Asian. If the criteria were met but the coder still hesitated over ethnic appearance, characters were discussed in a larger ethnic diverse team to reach a consensus (n = 24).

A White ethnic appearance was defined as a White skin color as well as Caucasian ethnic appearances (e.g., a character with White skin color, round eyes, and black hair were coded as White). Other ethnic appearance was coded if the characters were perceived as neither East Asian nor White (e.g., had a darker skin color or an ethnicity-related costume such as a taqiyah). Characters were coded as having an unclear ethnic appearance when their skin color was transparent (their face could not be distinguished from the colored background) or unnatural (e.g., red, blue), or when they were drawn in a position from which the ethnic features, such as face, skin, and hair, could not be seen clearly. Characters for which two out of three aspects (ethnicity, gender and age) could not be coded were not included in the dataset. Particularly, ethnic appearance was coded independent from the text indication (e.g., characters could be coded as White ethnic appearance based on figure illustration, although they were referred to as Chinese by names or in text). Based on ethnic appearance and name, a separate category, namely, characters with inconsistency between ethnic appearance and names or explicitly mentioned ethnicity, was coded.

Because the present study aims at a detailed investigation of ethnic physical feature representations in East Asian characters, the following variables were added to the coding system for East Asian appearance characters: eyes, skin tone, hair color, and hair style. Among the East Asian population, eyes with epicanthal folds are frequent (50% to 90%, Lee et al. 2000). When applied to illustrations, eyes drawn with a line, drawn in a slant manner, or open eyes with a clear single line drawn on the upper eyelid starting from the inner corner of the eye were coded as eyes with epicanthal folds. Closed eyes were coded as missing data for this variable. Skin tone in East Asian characters was classified as (0) light, (1) mid-tone, (2) somewhat dark, or (3) very dark. Example skin colors for each category were provided as a reference for the coders. Skin tone was coded as missing if skin of the characters was not clearly visible, or the same character in different pictures had very different skin tones, or the book was in black-and-White sketch style. In addition, hair color (black or not black) and hair style (straight and not straight) were coded among East Asian characters. Hair color and hair style were coded as missing if the characters were bald, wore a hat or scarf, or whose hair was not visible for other reasons.

Two coders (one Chinese and one Vietnamese American) independently coded ten random books including 112 human characters as the reliability set on the variables used by de Bruijn et al. (2020) (physical features variables not included in this phase). The first coder continued to code all the variables in all books. Reliability for the variables between that coder’s original coding and a consensus scores was between 0.92 and 1.00 (Cronbach’s α) for numeric variables and between 0.89 and 1.00 (Cohen’s ĸ) for nominal variables. In addition, physical features for the East Asian characters (n = 97) in the reliability set were then coded by three coders (two Chinese and a Vietnamese American) separately. The first coder also coded the physical features variables in all books. Reliability between the main coder’s original coding and the consensus reliability set of the physical features variables was between 0.86 and 0.94 (Cohen’s ĸ) for all variables.

Analyses

There were 75 books and 2177 human characters in the final dataset. Characters with unclear ethnic appearance (n = 305) were not included in the analyses at the character level. Moreover, among the 246 characters with explicitly mentioned ethnicity in the text (1% of the coded characters), ethnic information in the pictures and text were consistent. However, there were 14 characters with inconsistencies between their ethnic names and ethnic appearances. These 14 characters were presented as East Asian characters due to their explicitly mentioned East Asian names in text, but did not have an East Asian ethnic appearance in the pictures. All statistical analyses were done with and without these 14 ethnically inconsistent characters.

After calculating descriptive statistics, associations between ethnicity of the characters and ethnicity of the authors and illustrators were examined by Pearson Chi-Square tests. Fisher’s Exact Tests were used when the expected count in more than 20% of the cells was below five. Further, associations between ethnicity of the characters and the relative representation in pages and pictures were examined by a Mann–Whitney U test, as the variables were highly skewed (Zskew > 3.29). In addition, associations between ethnicity of the characters, and character gender, age group, role, having a name, and representation on the cover were also examined by Pearson Chi-Square tests. The analyses regarding indicators of prominence (representation in pages and pictures, role of the characters, having a name, being presented on the cover) were then conducted separately per gender of character. For physical feature representation, descriptive statistics on four physical feature illustrations, including eyes, skin tone, hair color, and hair style, were reported among East Asian characters. Further, Pearson Chi-Square tests were conducted to examine potential differences in terms of physical feature illustrations between East Asian male and female characters.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The study sample consisted of 75 books published between 2007 and 2018. Most books were published by Mingtian (n = 9), Jieli (n = 8), or Beijing associated publishers inc (n = 6). There were 2177 human characters in the books, of which ethnic appearance of 305 characters could not be coded. Therefore, 1872 characters were eventually included in the analyses of the sample books. Descriptive statistics of general information about the sample books are shown in Table 1. In addition, 14 characters had East Asian names but non-East Asian appearances, of whom 13 characters had an East Asian name with a White ethnic appearance, and one had an East Asian name with a dark skin color. These 14 inconsistent characters were first excluded (n = 1858) and then included (n = 1872) in the analyses at the character level to examine potential differences. All results were the same except ethnic representation in protagonists at the character level. Results without the 14 inconsistent characters were reported.

Authors and illustrators

Of the 75 books included in the research, most books (n = 68) were written by one author, while six books were written by two authors. One book was a wordless book, and thus no author was coded. Specifically, the books were written by 75 different authors, of whom 61% were East Asian and 39% were White. After exclusion of six gender-unknown authors, 45% of the authors were female. For 32 books, the authors also illustrated the books. Most books (n = 71) were illustrated by one illustrator while four books were illustrated by two. The pattern was similar for ethnicity of the illustrators (n = 72): 58% were East Asian, 39% were White, and 3% had a different ethnic background (Arab and Latin American). After exclusion of four gender-unknown illustrators, 41% of the illustrators were female.

Results of Pearson Chi-Square tests to examine the association between ethnicity of the author and the illustrator and books containing only White characters, only East Asian characters or both White and East Asian characters are presented in Table 2. There was a significant association between ethnicity of the characters in books and ethnicity of the author [χ2 (2, N = 72) = 7.50, p = 0.023] and illustrator [χ2 (2, N = 73) = 11.72, p = 0.003]. As may be expected, the books containing only East Asian characters were more often written by East Asian authors (z = 2.08, p = 0.037) and illustrators (z = 2.69, p = 0.007), the books containing only White characters were more often written by non-East Asian authors (z = 2.64, p = 0.008) and illustrators (z = 3.26, p = 0.001), and books containing both White and East Asian characters showed no significant difference between ethnicity of the author and illustrator.

Characters

Of the 1858 characters with a clear ethnic appearance, 50% were White, 40% were East Asian, and 10% were of other ethnicities. Patterns for protagonists (45% White, 42% East Asian, and 13% other ethnicities) and secondary characters (53% White, 32% East Asian, and 15% other ethnicities) showed that White characters were consistently the largest category, followed by East Asian characters. There was an exception for background characters (47% White, 47% East Asian, and 6% other ethnicities), as White and East Asian background characters were similarly represented. With inclusion of the 14 characters with inconsistent ethnic names and ethnic appearances, the patterns for all characters, secondary characters, and background characters were the same. However, we identified more East Asian protagonists (47%) than White protagonists (42%) and other protagonists (11%) in children’s books.

Comparison between age groups and gender of White and East Asian appearance characters was also analyzed (see Table 3). There was a significant association between ethnic appearance of the characters and gender [χ2 (2, N = 1668) = 9.63, p = 0.008]. For both East Asia and White characters, males were more likely to be represented than females. More specifically, male characters were represented more among East Asian characters than among White characters (z = 2.83, p = 0.004), while female characters were represented more among White characters than among East Asian characters (z = 2.46, p = 0.013). There were no significant associations between ethnic appearance of the characters and age groups.

Prominence

The associations between ethnic appearance and prominence factors were investigated. Different from the ethnic distribution of characters, the relative representation in pages (representation on number of pages relative to total number of pages in the book) was higher for East Asian characters (Mdn = 0.03) than for White characters (Mdn = 0.02, U = 243,943.00, p < 0.001). Similarly, a significantly higher relative representation in pictures was found for East Asian characters (Mdn = 0.04) than for White characters (Mdn = 0.01, U = 231,442.50, p < 0.001). In addition, there were significant associations between ethnic appearance of the character and role, having a name, and cover representation (see Table 3). Comparing the character role, both East Asian and White characters were equally likely to be the protagonist, while East Asian characters were significantly less represented as secondary characters (z = − 5.19, p < 0.001), and more as background characters (z = − 4.91, p < 0.001).

The associations between ethnic appearance of the character and the indicators of prominence were then separately analyzed for male and female characters. Among the 1858 sample characters, it was shown that a significantly higher relative representation in pages was found for both East Asian males (Mdn = 0.03, U = 85,220.00, p < 0.001) and East Asian females (Mdn = 0.03, U = 38,096.00, p < 0.001). Likewise, a significantly higher relative representation in pictures was also found for both East Asian males (Mdn = 0.04, U = 75,818.50, p < 0.001) and East Asian females (Mdn = 0.04, U = 38,883.50, p < 0.001). In addition, there was no significant association between ethnic appearance and character roles for females, but there was for males [χ2 (2, N = 971) = 43.60, p < 0.001]. Specifically, White male characters (50%) were represented as secondary characters more often than East Asian male characters [30%, χ2 (1, N = 971) = 23.90, p < 0.001], whereas East Asian male characters (66%) were represented as background characters more often than White male characters [45%, χ2 (1, N = 971) = 42.60, p < 0.001]. Further, East Asian males (4%) were less likely to have names than White male characters [12%, χ2 (1, N = 971) = 24.23, p ≤ 0.001], but there was no significant association between ethnic appearance and having a name for female characters. Conversely, East Asian female characters (10%) were more likely to appear on the cover than White female characters [4%, χ2 (1, N = 675) = 8.943, p = 0.003], whereas there was no significant association between ethnic appearance and cover appearance for males.

Physical features

The 14 characters with inconsistencies between their ethnic names and ethnic appearances were excluded from analyses regarding physical features. To summarize, for all the physical features that can be observed, 84% of the East Asian characters (n = 579) had epicanthal folds. East Asian characters (n = 694) had 26% light, 52% mid-tone, 16% somewhat dark, and 5% very dark skin tone. Moreover, 79% of the East Asian characters (n = 619) had black hair and 95% of the East Asian characters (n = 587) had straight hair.

Results of Pearson Chi-Square tests to examine the association between physical features in East Asian characters and character gender are presented in Table 4. As can be seen, eyes with epicanthal folds were shown significantly more in East Asian female characters than in East Asian male characters [χ2 (1, N = 573) = 6.72, p = 0.010]. In contrast, straight hair was shown more in East Asian male characters than East Asian female characters [χ2 (1, N = 583) = 13.77, p < 0.001]. There was no significant difference in female and male skin tone distribution, although the comparison showed a trend towards significance [χ2 (3, N = 689) = 7.39, p = 0.060]. East Asian female characters were somewhat more likely to be illustrated with a light skin tone but less likely with a very dark skin tone than East Asian male characters. Finally, no significant association was found between hair color and character gender.

Discussion

The present study aimed to shed light on the ethnic representation of authors, illustrators, and characters of books for young children in China that (1) won awards or (2) were in the annual sales ranks of one of the most popular online book stores in China from 2011 to 2018. Results demonstrated that the authors and the illustrators are predominantly East Asians, while more White rather than East Asian characters were found in the Chinese books for young children. More male than female characters, especially among East Asians, were depicted in the books. For some indicators East Asian characters were more prominent, especially females, whereas for the other indicators White characters were more prominent, especially males. Gender differences in physical feature illustrations in East Asian characters were found in terms of eye shape and hair style.

The results of the present study indicated a predominance (just over half) of East Asian authors and illustrators, suggesting many opportunities for role models for Chinese young children (Hughes-Hassell et al. 2009). However, when considering that almost the entire Chinese population is East Asian (> 99.4%; NBS 2020a), this finding actually reflects an underrepresentation of East Asian authors and illustrators as compared to the population. In Canada, the Netherlands, and the United States, a higher degree of dominance (White authors and illustrators over 80%) was found in popular books for young children (e.g., de Bruijn et al. 2020; Dionne 2014; Koss 2015). Therefore, it is safe to conclude that the degree of dominance of East Asian authors and illustrators in popular children’s books in China is smaller than that of White authors and illustrators in children’s books in North Atlantic countries.

In addition, the largest ethnic category of the characters was White, followed by East Asian. This result suggests that Chinese children are less likely to see East Asian characters (who are more likely to look similar to them) than White characters. This might lead Chinese children to have fewer opportunities to identify with a character and to be less connected to the character’s experience and emotions (Slater and Rouner 2002; Witmer and Singer 1998), and thus contributing to potential lower reading motivation (Hughes-Hassell et al. 2009). In addition, the higher representation of White characters than East Asian characters in Chinese children’s books is in line with earlier studies on the popularity of, for example, Caucasian and Eurasian models and celebrities in Asia (Goon and Craven 2003; Stohry et al. 2021), and adds to this body of research by showing this pattern in children’s literature.

An overrepresentation of White authors, illustrators, and characters in Chinese children’s books reflects the White preference on China’s book market. This is due to decisions by the publication import entities who take the market demand into account. Chinese parents show a strong demand for imported books due to a lack of satisfactory contemporary children’s books written by Chinese authors and illustrators (e.g., stories about ancient China are distant from the life of contemporary Chinese children, old-fashioned painting styles; Yang 2012). The censorship of the press by the administrative department for publication in China seldom applies to the books for young children because the criteria used for censoring mainly aim to exclude, for example, books against China’s sovereignty and territorial integrity (Regulations on the Administration of Publication 2001, cl 45–46). This means that children’s books are very likely to be approved for import. Therefore, the children’s books market in China gradually shows a high proportion of imported books resulting in Chinese children's being continuously exposed to White (Western) contexts, cultures, and norms, including White-normative messages about physical appearance from picture books.

It is also interesting to note that ethnicity of the author was related to ethnicity of the characters: the books with characters all from one specific ethnic group were written by authors and illustrators of that same ethnic group. There is evidence that insiders depict their cultural traditions and its people the most authentically and qualitatively in literature (Bista 2012). Thus, Chinese children are likely to be exposed to authentic characters and stories about the East Asian (especially in the books containing only East Asian characters) and the White group (especially in the books containing only White characters).

At the character level, gender and age of the characters were analyzed in this study as two other salient factors in terms of identification for children (Chen et al. 2016). In general, consistent with findings in other countries (de Bruijn et al. 2020; Hamilton et al. 2006), males were overrepresented among both White and East Asian characters. Furthermore, a significant association between gender and ethnicity was found, indicating a bigger gender representation gap for East Asian characters. This result suggests that girls may have more difficulty identifying with characters, especially with East Asian characters, based on the similarity identification hypothesis (Cohen 2001). No significant intersection between gender and ethnicity was found in the previous studies of Western books for young children (e.g., de Bruijn et al. 2020; Eisenberg 2002). A possible explanation for a higher dominant level of East Asian male characters might be the patriarchal demographics in contemporary China, with its skewed gender ratio favoring males because of the preference for boys in traditional Chinese culture, especially under the one-child policy between the 1980s to the year 2015. In fact, the gender gap in the children books in the present study (166 male to 100 female characters) was bigger than those of the newborn baby and total population statistics (approximately 120 newborn boys to 100 girls; 105 males to 100 females in total population; Abrahamson 2016; Greenhalgh 2013; NBS 2020b). Given that children’s books are an important source of new concepts and morals for young children, equal representation of male and female characters is important.

In addition, indicators of prominence of characters were examined because they can provide more information about the degree in which the audience gets acquainted with a character. The present study indicated that East Asian characters were represented on a relatively higher number of pages and pictures than White characters. This may be explained by the types of books in which the two groups of characters are represented. The books by East Asian authors and illustrators (generally with East Asian characters) had a lower number of characters on average so that one character would make up a higher proportion of characters. Moreover, East Asian characters, especially females, were more often on the cover than White characters. Because only eight more East Asian than White characters were shown on the cover in all sampled books, it is difficult to draw strong conclusions from this finding. Future research is needed to replicate this result in larger samples to see a clearer pattern.

Lower character prominence in terms of roles and names was found for East Asian characters. There may be multiple explanations for this finding. Firstly, the cultural trait of collectivism, i.e., to work as a group rather than the emphasis on individual worth and initiative that is typical for East Asian culture, may be reflected in more group than individually prominent representation of East Asian characters (Lui and Rollock 2018). The representation of non-prominent East Asian characters in books written by White authors and illustrators may reflect diversity efforts, that is, tokenism, which may activate negative stereotypes associated with the tokenized identity (Paul et al. 2020). We also found that character prominence in terms of roles and names was higher for East Asian females than males. This result seems contradictory to the underrepresentation of females in children’s books, but is likely due to the fact that books for children under 6 years old often include family or (pre-)school settings with adult female characters that typically fulfill prominent roles in these contexts (e.g., mothers, teachers, child care professionals). It appears that the high prominence of women in young children’s lives in real life is mirrored in these children’s books.

Physical features among East Asian characters were analyzed because the illustration of characters could transmit preferences for specific physical features to young children. The present study showed a higher percentage of light and a lower percentage of dark skin tone for illustrated East Asian characters than for the actual East Asian population (a small percentage of people have light skin color, the majority has intermediate or somewhat dark skin color; Liu et al. 2007). This result may bring potential skin color biases, supported by colorism, between persons of the same ethnicity in which someone with a lighter complexion is considered more beautiful and seen as having a higher social and economic status than someone with dark skin tone (Sconiers 2018; Yu 2021). Chinese children may therefore develop (or strengthen) a White or light skin tone preference, and those who have a dark skin tone themselves may have a higher risk of negative self-evaluation in terms of appearance (Thompson and Heinberg 1999; Rice et al. 2016). The result showed a trend towards significance towards more light skin tone and less dark skin tone for female characters, which is consistent with the observations that colorism is gendered, and especially prominent in the lives of females (Alexander and Carter 2022; Hill 2002; Wilder and Cain 2011). Previous studies indeed indicated that East Asian people have a preference for White or lighter skin color, and Chinese males had a stronger preference for lighter skin color Chinese women (Krishen et al. 2014).

In addition, the frequencies of eyes illustrated with epicanthal folds in the books for young children were at the top of the range in the East Asian population (50–90%; Lee et al. 2000), and more often seen in East Asian female than male characters. There was no evidence of a preference for (East Asian) characters without epicanthal folds in the books, suggesting that they do not contribute to such preference in children, especially for the beauty ideals for East Asian females. Similarly, ethnically typical straight hair was most common in illustrated East Asian characters, higher than the highest percentage in Chinese population statistics (64–91%; Tan et al. 2013), although more often illustrated among males than females. Further, the majority of characters had black hair (no national comparison statistic available). This result suggests no promotion of preference for hair types uncommon to East Asian people. In short, the physical features presented in the books as compared to population statistics show that light skin color is overrepresented, and other typical features are in the high ranges of representation.

Several limitations of the present study should be discussed. Firstly, 21 of the 75 sample books were part of a series, and only the first book in the list of each series was selected, as some of the series consisted of a large number of books (up to 100). Although ethnic representation in each book in a specific series is generally similar considering the consistent social contexts in stories, children might be exposed to characters with specific ethnic backgrounds more often if they have multiple books of the same series and spend more time reading books in a series than those who are not part of one. Given that the ethnic representation gap is bigger in books from series, with a lower percentage of East Asian characters, children may in fact be exposed to even fewer East Asian characters than reported in this study. Secondly, the results on skin tones should be interpreted cautiously, because bias in color categorization, for example, the influence of the colors surrounding a human character in a picture, is almost impossible to be avoided by a human coder. Digital methods for face recognition and skin tone categorization have been considered to mitigate this problem. However, rotated faces cannot yet be successfully recognized by the computers (Jha et al. 2018), limiting the usefulness of this method. Further research with more objective color categorization following the development of digital methods for face recognition and skin tone categorization is needed. Lastly, it is important to note that the internet and social media were not studied in the present study although they may also play a large role in globalization and the preference for White people and culture in China. However, young children under 6 years old generally have very limited access to the internet. Researchers could include multiple types of media, for example, social media and books for formal schooling, in future studies aimed at older children.

Conclusion

The present study pioneers the investigation of ethnic representation issues in East Asia by examining books for young children (6 years old and under) in China, by examining both the ethnic representation statistics and indicators of prominence of characters, and by examining the frequency of physical features illustrated in East Asian characters. The results reveal an overrepresentation of White authors, illustrators, and characters as compared to population statistics, as well as a light skin color preference for East Asian characters in illustrations in books for young children in China. White prevalence and White preference in Chinese children’s books are driven by the promotion of publication import entities under a demand for imported books among Chinese parents, and are not hindered by the censorship of the press. These mechanisms may reflect a form of postcolonial globalization influencing children’s literature in China, i.e., overrepresentation of White culture and underrepresentation of ethnic culture in books with the educational function in China at younger level. The results can help us understand the potential early childhood origins of the preference for White people and culture in China.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abrahamson P (2016) End of an era? China’s one-child policy and its unintended consequences. Asian Soc Work Policy Rev 10(3):326–338. https://doi.org/10.1111/aswp.12101

Alexander T, Carter MM (2022) Internalized racism and gendered colorism among African Americans: a study of intragroup bias, perceived discrimination, and psychological well-being. Journal of African American Studies (New Brunswick, N. J.) 26(2):248–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12111-022-09586-2

Beijing OpenBook co., Ltd (2018) Quanqiu beijing xia de 2017 Zhongguo tushu lingshou shichang qushi (The annual aggregated report of China’s book retail market 2017). Kaijuan Wenzhai 2:4–5

Bista K (2012) Multicultural literature for children and young adults. Educ Forum 76(3):317–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131725.2012.682203

Chen M, Bell RA, Taylor LD (2016) Narrator point of view and persuasion in health narratives: the role of protagonist-reader similarity, identification, and self-referencing. J Health Commun 21(8):908–918. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2016.1177147

Chuban guanli tiaoli (Regulations on the Administration of Publication) (promulgated by the State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 25 December 2001, effective 1 February 2002). http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2020-12/26/content_5574253.htm. Accessed 9 Sept 2021

Cohen J (2001) Defining identification: a theoretical look at the identification of audiences with media characters. Mass Commun Soc 4(3):245–264. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327825MCS0403_01

de Bruijn Y, Emmen RAG, Mesman J (2020) Ethnic diversity in children’s books in the Netherlands. Early Child Educ J 49(3):413–423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-020-01080-2

Dionne A (2014) Multicultural children’s books at the French Canadian public library: where can I find them? Qual Quant Methods Libraries (QQML) 1:183–190

Dittmar H, Halliwell E, Ive S (2006) Does Barbie make girls want to be thin? The effect of experimental exposure to images of dolls on the body image of 5- to 8-year-old girls. Dev Psychol 42(2):283–292. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.283

Drew J (1999) Cultural composition: Stuart hall on ethnicity and the discursive turn. In: Olson G, Worsham L (eds) Race, rhetoric, and the postcolonial. SUNY Press, New York, pp 205–239

Eisenberg KN (2002) Gender and ethnicity stereotypes in children’s books (Doctoral dissertation). https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.leidenuniv.nl:2443/docview/251657696?pq-origsite=primo

Garner PW, Parker TS (2018) Young children’s picture-books as a forum for the socialization of emotion. J Early Child Res 16(3):291–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X18775760

Gibson B, Robbins E, Rochat P (2015) White bias in 3–7-year-old children across cultures. J Cogn Cult 15(3–4):344–373. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685373-12342155

Goon P, Craven A (2003) Whose debt?: Globalisation and White-facing in Asia. Intersections: gender, history and culture in the Asian context, 9. http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue9/gooncraven.html. Accessed 10 Sept 2021

Greenhalgh S (2013) Patriarchal demographics? China’s sex ratio reconsidered. Popul Dev Rev 38:130–149

Hamilton MC, Anderson D, Broaddus M (2006) Gender stereotyping and under-representation of female characters in 200 popular children’s picture books: a twenty-first century update. Sex Roles 55(11):757–765. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9128-6

Hill ME (2002) Skin color and the perception of attractiveness among African Americans: does gender make a difference? Soc Psychol Q 65(1):77–91. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090169

Hughes-Hassell S, Cox EJ (2010) Inside board books: representations of people of color. Libr Q 80(3):211–230. https://doi.org/10.1086/652873

Hughes-Hassell S, Barkley HA, Koehler E (2009) Promoting equity in children’s literacy instruction: using a critical race theory framework to examine transitional books. Sch Libr Media Res 12:1–20

Jha S, Agarwal N, Agarwal S (2018) Towards improved cartoon face detection and recognition systems. http://arXiv.org/abs/1804.01753

Ji Y (2012) 3–6 Sui Youer Jiating Qinzi Yuedu Xianzhuang Diaocha (Investigation on parent-child reading among 3-6-year-old children). Youer Jiaoyu (Jiayu Kexue) 1(2):77–80

Koss M (2015) Diversity in contemporary picturebooks: a content analysis. J Child Lit 41(1):32–42

Koss M, Martinez MG, Johnson NJ (2017) Where are the Latinxs?: diversity in caldecott winner and honor books. Biling Rev 33(5):50–62

Krishen AS, LaTour MS, Alishah EJ (2014) Asian females in an advertising context: exploring skin tone tension. J Curr Issues Res Advert 35(1):71–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.2014.866851

Kurz RF (2012) Missing faces, beautiful places: the lack of diversity in South Carolina picture book award nominees. New Rev Child Lit Librariansh 18(2):128–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614541.2012.716695

Lan S (2016) The shifting meanings of race in China: a case study of the African diaspora communities in Guangzhou. City Society 28(3):298–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/ciso.12094

Lee Y, Lee E, Park WJ (2000) Anchor epicanthoplasty combined with out-fold type double eyelidplasty for Asians: do we have to make an additional scar to correct the Asian epicanthal fold? Plast Reconstr Surg 105(5):1872–1880. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-200004050-00042

Li EPH, Min HJ, Belk RW, Kimura J, Bahl S (2008) Skin lightening and beauty in four Asian cultures. Adv Consum Res 35:444–449

Li C, Liu Y, Jian W (2018) Youer jiating qinzi huiben yuedu xianzhuang diaocha yanjiu (The research on parent-child picture book reading present situation of infant family). Kashi Daxue Xuebao 39(1):110–115

Liu Y, Croucher S (2022) Becoming privileged yet marginalized other: American migrants’ narratives of stereotyping-triggered displacement in China. Asian J Soc Sci 50(1):7–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajss.2021.06.006

Liu W, Wang X, Lai W, Li L, Zhang P, Wu Y, Lu Y, Li Y, Tian Y, Wu Y, Chen L (2007) Skin color measurement in Chinese female population: analysis of 407 cases from 4 major cities of China. Int J Dermatol 46(8):835–839. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03192.x

Lui PP, Rollock D (2018) Greater than the sum of its parts: development of a measure of collectivism among Asians. Cult Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 24(2):242–259. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000163

Mak AKY (2007) Advertising whiteness: an assessment of skin color preferences among urban Chinese. Int J Phytorem 21(1):144–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/15551390701670768

NBS (2020a) Di qi ci quanguo renkou pucha gongbao (di ba hao) (Report for the seventh national population census (number 8)). http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/202105/t20210510_1817184.html. Accessed 11 Mar 2022

NBS (2020b) Di qi ci quanguo renkou pucha zhuyao shuju qingkuang (Main Data situations of the seventh national population census). http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/202105/t20210510_1817176.html. Accessed 11 March 2022

Paul I, Parker JR, Dommer SL (2020) The influence of incidental tokenism on private evaluations of stereotype-typifying products. Soc Psychol Q 83(1):49–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272519865502

Qian MK, Heyman GD, Quinn PC, Messi FA, Fu G, Lee K (2016) Implicit racial biases in preschool children and adults from Asia and Africa. Child Dev 87(1):285–296

Rhee SC, Woo KS, Kwon B (2012) Biometric study of eyelid shape and dimensions of different races with references to beauty. Aesth Plast Surg 36(5):1236–1245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-012-9937-7

Rice K, Prichard I, Tiggemann M, Slater A (2016) Exposure to barbie: effects on thin-ideal internalisation, body esteem, and body dissatisfaction among young girls. Body Image 19:142–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.09.005

Russell KY, Wilson M, Hall RE (1992) The color complex: the politics of skin color among African Americans. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York

Sconiers ND (2018) Color-struck: a look at the influence of skin tone on the racial identities and self-perceptions of African-American women (Doctoral dissertation). https://search.proquest.com/openview/eee37c0b735cac261f7e80ad2d69e0d7/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

Slater MD, Rouner D (2002) Entertainment-education and elaboration likelihood: understanding the processing of narrative persuasion. Commun Theory 12(2):173–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2002.tb00265.x

Stohry HR, Tan J, Aronson BA (2021) The enemy is White supremacy. In: Hayes C, Carter IM, Elderson K (eds) Unhooking from Whiteness. Brill, Leiden. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004389502_013

Tan J, Yang Y, Tang K, Sabeti PC, Jin L, Wang S (2013) The adaptive variant EDARV370A is associated with straight hair in East Asians. Hum Genet 132(10):1187–1191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-013-1324-1

Thompson JK, Heinberg LJ (1999) The media’s influence on body image disturbance and eating disorders: we’ve reviled them, now can we rehabilitate them? J Soc Issues 55(2):339–353. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00119

Wilder J, Cain C (2011) Teaching and learning color consciousness in Black families: exploring family processes and women’s experiences with colorism. J Fam Issues 32(5):577–604. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X10390858

Witmer BG, Singer MJ (1998) Measuring presence in virtual environments: a presence questionnaire. Presence 7(3):225–240. https://doi.org/10.1162/105474698565686

Yang A (2012) Zhongguo yuanchuang tuhua shu: Lixiang yu daolu (Chinese original picture books: the ideal and the road). Zhongyang Minzu Daxue Xuebao (zhexue Shehui Kexueban) 39(4):156–160

Youngs E (2015) Effects of multicultural literature on children’s perspectives of race and educator implementation of multicultural literature. Education Masters. Paper 319

Yu T (2021) Examining colourism in China. In: Halse C, Kennedy KJ (eds) Multiculturalism in turbulent times, 1st edn. Routledge, Oxfordshire. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003090090

Acknowledgements

Support from the China Scholarship Council (CSC) (Grant No. 201808110198) is gratefully acknowledged. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the CSC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that there are no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Y., Emmen, R.A.G., de Bruijn, Y. et al. White prevalence and White preference in children’s books in China. SN Soc Sci 2, 228 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-022-00540-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-022-00540-3