Abstract

Regulators and pharmaceutical companies across the world are intensifying efforts to get increasingly complex and innovative drugs to patients with high unmet medical need in the shortest possible time frame. This article reviews pathways to expedite drug development and approval available in member countries of the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use and Australia. It is concluded that the increasing availability of expedited regulatory pathways and associated modernisation of regulatory systems changes the current regulatory paradigm and requires sponsors to rethink drug development and regulatory strategy. A transformation of the current sequence of regulatory submissions, favouring those countries/collaborations that are best regulatory equipped to make innovative medical need drugs available to patients in the shortest time frame is imminent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Development of new drugs is a challenging and complex process associated with long development timelines and clinical trial success rates for compounds entering phase I of around 10% [1, 2]. This is despite the publication of many scientific guidelines, interactions/meetings with regulators and the establishment of dedicated review timelines by regulatory agencies in many countries. To accelerate patient access to treatment mainly in areas of serious and life-threatening diseases and unmet medical need, many regulatory authorities have put in place regulatory pathways to expedite drug development and approval. Initially, expedited pathways were introduced in the early 1990s in the United States of America (US) stimulated by the intention to allow antiretroviral treatments for patients to become available as quickly as possible to counter the threat of the AIDS pandemic [3].

Generally, the following regulatory options are available globally to expedite the development and approval of innovative drugs in areas of serious and life-threatening diseases and unmet medical need:

-

1.

Initial authorisation based on limited clinical data In most countries, this pathway includes regulatory approval based on a surrogate or early endpoint. Approval through this pathway needs to be complemented by further clinical data generated post-authorisation as laid out in commitments, such as Accelerated Approval in US or Conditional Marketing Authorisation in the EU.

-

2.

Repeated increased interaction between the regulator and the sponsor This option focusses on increased frequency of interactions starting early and continuing throughout drug development and involves designations as Breakthrough and Fast Track in the US or Priority Medicine (PRIME) in the EU.

-

3.

Shortened registration pathways These pathways are intended to shorten the regulatory review timelines by health authorities. Regulatory agencies provide additional resources to expedite the review and evaluation of regulatory submissions. This includes pathways such as Priority Review in US or Accelerated Assessment in the EU. Other regulatory pathways that are based on reliance are not in scope of this article.

The aim of this regulatory review article is to provide an overview of the key characteristics of regulatory expedited pathways across members of the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). Furthermore, the aim is to discuss the potential impact on development and approval when these pathways are used. Only ICH member countries and Australia were selected since they are important markets for drug developers and the possibility to reduce drug development timelines and avoid duplication of work will have high impact. Although Mexico is ICH member since November 2021, all the regulatory pathways currently available in Mexico to expedite review are based on reliance and hence not discussed in this article.

Future regulatory perspectives, anticipating an evolving regulatory landscape aiming for expedited approvals in different regions, with potential consequences for future company submission and launch sequence strategies are also discussed. These include recent pilot collaborations such as Australia, Canada, Singapore, Switzerland and UK (Access consortium) and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-led Project Orbis.

Materials and Methods

A systematic search and in-depth analysis of information and guidelines provided by national regulatory agencies on expedited pathways was conducted, including all information available up to December 2021. In case of language barriers local regulatory experts verified guidelines content and meaning. This analysis was complemented with:

-

Information from a regulatory intelligence database (Cortellis)

-

Context from relevant published literature

-

Information published on Health Authorities’ websites

Corresponding source documents and literature are included as references.

The authors would like to point to FRPath.org, an educational project designed to serve as the trusted repository of expertly evaluated and organized information about Facilitated Regulatory Pathways, although this source was not used for the purpose of this paper.

Results

Country-Specific Information on Available Expedited Pathways

The most recent information and procedure details collected on regulatory pathways in different ICH members is summarised in the Tables 1, 2 and 3 (countries listed in alphabetical order). The tables classify the regulatory pathways according to the criteria “Initial authorisation based on limited clinical data” (Table 1); “ Repeated, increased agency interaction” (Table 2) and ‘Shortened registration pathways ‘ (Table 3).

Table 1 illustrates that authorisation based on limited clinical data is a regulatory option in all ICH members but differences in eligibility and scope exist. In the case of Singapore, no specific guideline is available but during the COVID-19 pandemic, remdesivir was conditionally authorised demonstrating that in emergency situations the possibility exists.

Repeated, increased interaction between the regulator and the sponsor is a more recent regulatory tool to expedite drug development. Thus far, Brazil, China Breakthrough Designation (BTD), US FDA (BTD and Regenerative Medicine Advance Therapy (RMAT) program), EU (PRIME), Japan (Sakigake), Korea and Taiwan offer this option of repeated, close engagement with the Health Authority during drug development. In many cases, drugs that qualify for an increased interaction pathway are also eligible for one or more of the other expedited pathways (Table 2).

As summarized in Table 3, regulators in all ICH members offer shortened marketing authorisation application review pathways. Eligibility requirements and scope differ across ICH members. Shorter pathways are mostly achieved through repeated, intensified development and pre-submission interactions, expedited review or rolling or split submissions or a combination of these.

Additional Regulatory Collaborations—Perspectives

To further enhance the efficiency of national regulatory systems, regulatory authorities are also looking for alignment and creating synergy, with the aim to reduce duplication and bring innovative drugs to patients in their countries as early as possible. Several initiatives such as Project Orbis, Access consortium, and the ASEAN joint assessment have been started that seek to share review experience and burden and to foster close exchange between participating regulators, preferably throughout the life cycle of a drug (Table 4).

Project Orbis

Project Orbis, an initiative from FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence provides a framework for concurrent submission and review of oncology drugs among partner international regulatory agencies [4]. This initiative was launched in 2019 with three participating agencies (FDA, the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) and Health Canada); however, new Participating Orbis Partners (POP) were recently added such as Singapore’s Health Sciences Authority (HSA), Switzerland’s SwissMedic, Brazil’s ANVISA, UK’s Medicines & Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and Israel’s Ministry of Health (MoH) [5,6,7,8,9].

Submitted dossiers are similar in content but must meet national regulatory requirements of each country. The review process is based on collaborative review (involving FDA as primary coordinator plus at least one of the POPs) but each of the POPs performs its own review and remains fully independent in making its regulatory decision. Mutual confidentiality agreements have been set up to allow to share assessment information among partners. Cross-functional assessments are facilitated through an Assessment Aid (FDA template) and questions can be coordinated by FDA (but each POP can send questions).

In the first year of the project (June 2019–June 2020) a total of 60 oncology marketing applications were received. The first New Medical Entity (NME) under Orbis was approved on April 17, 2020. The median time gap in the submission date to the FDA and to the POP was 0.6 months (range −0.8 to 9.0 months). The median time to approval was similar between FDA (4.2 months, range 0.9–6.9 months, N = 18)) and the POP (4.4 months, range 1.7–6.8, N = 20) [10].

Access Consortium

Initiated in 2007, the Access (formerly ACSS) Consortium is a coalition of ‘like-minded’, medium-sized regulatory authorities (currently Australian TGA, Health Canada, SwissMedic, HSA Singapore and UK MHRA) that work together to promote greater regulatory collaboration and alignment of regulatory requirements [11]. It also aims to bring drugs faster to patients. Access offers a work sharing pilot for coordinated assessment of new applications or indication extensions filed in at least two Access countries. A single assessment of a common dossier (Module 2–5) facilitated via work-sharing between participating members is followed by a national step where each jurisdiction takes separate sovereign approval and labelling decisions. All participating countries need to agree on either standard or priority review. In contrast to project Orbis, Access review can be requested for drugs for any therapeutic area. Since the first simultaneously reviewed Access submission in 2017 until July 2021, 12 drug submissions have been evaluated; 16 drugs are under active review; and an additional seven applications are in pre-filing planning [12].

ASEAN Joint Assessment

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is a collaboration of 10 member states aiming to accelerate economic growth, social progress and cultural development. The collaboration also includes harmonisation of regulatory requirements for pharmaceutical drugs. Participation is open to all ASEAN National Regulatory Agencies (NRA) on a voluntary basis and is specific for the drug being assessed. The Joint Assessment Coordinating Group (JACG) will assist NRAs to define drugs eligible for the joint assessment procedure, supported by a list of priority pharmaceutical drugs which will be periodically reviewed and published. Joint assessment will be implemented when a minimum of three NRAs decide to participate. For each joint assessment, a lead NRA will be appointed who coordinates and facilitates the assessment work. The final decision on the application will be made through the regular decision-making process of each participating country. A stable ASEAN-wide IT platform is being developed to support the operation of the collaborative processes (dossier submission, online review, consolidated list of questions, online responses from sponsors and joint assessment reports). The JACG has completed two joint assessments (both concerning antimalarial drugs). In one of the examples, all steps of the process up to release of the final joint assessment report were completed in less than 5 months [13].

EMA Pilot Project OPEN—most recently, triggered by the COVID pandemic, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) launched in December 2020 the OPEN pilot to increase international collaboration on the evaluation of COVID-19 vaccines and therapeutics. The objective is to share scientific expertise, while each agency remains fully independent. Participating agencies are the TGA, Health Canada, the Japanese Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA), SwissMedic and the World Health Organization (WHO). EMA will evaluate the pilot and has announced publicly to expand the OPEN scheme to antimicrobial resistance; quality topics / variations, products going through the PRIME scheme and medicines combating health threats or public health emergencies [14].

Discussion

In an effort to improve factors that impact timelines for drug development and approval, all ICH members have established pathways with expedited review timelines and initial approval based on limited clinical data as part of their regulatory toolkit. Pathways offering repeated, increased interactions with regulators to expedite drug development are established by many but not all ICH members. A possible explanation may be that these interactions are resource intense. The FDA has the longest experience with expedited pathways. Both priority review and accelerated approval were introduced in 1992. Other jurisdictions are rapidly catching up and have initiated pathways that shorten review timeline (in particular China, but also Brazil for rare diseases, Taiwan, Republic of Korea). ICH membership is expected to have a positive impact on this process and the growing scientific expertise may increase further availability of increased interaction pathways for the often more complex high medical need drugs. Similarly, by being a new ICH member, it is expected that Mexico will modernise its regulatory environment in the near future.

The FDA’s Breakthrough Therapy Designation and Fast Track designation have been well established as development regulatory tools for over a decade and have contributed significantly to expedite drug development. BTD is one of the most sought designations for drugs for serious conditions where preliminary clinical evidence indicates that the drug may demonstrate substantial improvement over available therapy on a clinically significant endpoint(s). Other ICH members have started to offer repeated, increased interaction between the agency and the sponsor during development. Examples are Japan (pioneering drug designation previously referred to as SAKIGAKE) and the EU (PRIME—PRIority MEdicines), but also several of the emerging markets such as China (Breakthrough designation) and Taiwan (Breakthrough Therapy). The UK, now independent from the EU, has introduced ILAP—Innovation Licensing and Access Pathways, which not only involves the regulators but also important payers (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and Scottish Medicines Consortium). When pursuing respective designations sponsors must align them with the subsequent filing strategy/sequence: for example, upholding of a Sakigake designation requires the first global filing to be in Japan or simultaneous in another first country.

Utilization of Expedited Pathways Across ICH Members

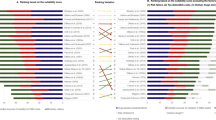

The extent to which the expedited pathways are being used and the impact on the median approval times have been analysed for a number of jurisdictions as part of the Centre for Innovation and Regulatory Science (CIRS) annual analysis of New drug approvals across indications by six major regulatory agencies (EMA, FDA, PMDA, Health Canada, SwissMedic and TGA) [15].

The CIRS data show that the use of expedited review versus standard review pathway differs greatly between jurisdictions. It is highest in the US where 71% of New Drug Approvals were reviewed under the expedited pathway (Priority review) in 2020, followed by Japan (45%), Canada (26%) and Australia (14%). The EU and Switzerland have the lowest percentage of expedited review (Accelerated Assessment) of completed new marketing authorisation applications (9% and 8% respectively). For the EU this might be impacted by the fact that drugs that are eligible for accelerated assessment often (50–60%) revert to the standard timelines, in case major objections are raised in the course of the assessment [16]. Between 2016 and 2020, over half (35 of 67) of Accelerated Assessment requests for non-PRIME designated drugs were rejected as compared to about 15% (3 out of 22) for PRIME designated drugs [16, 17]. Based on these figures, the ongoing revision of the EU pharmaceutical legislation provides an excellent opportunity to revisit EU’s expedited tools and how they are combined to gain competitive advantage when compared to other regulatory authorities (e.g., FDA; PMDA).

When focussing on review time gain (Table 5), a rather consistent gain of around 40% emerges between the ICH members for expedited versus standard marketing authorisation application review.

A CIRS survey in 2019 showed that both FDA’s BTD and PMDA’s pioneering drug designation (Sakigake) had a positive qualitative impact both within companies and outside (patients, physicians, regulators and investors) [18]. FDA fast track and EMA PRIME were less positively valued in this qualitative survey. PRIME is less valued due to the short time window of application and lack of availability for new indications. The drawbacks are recognised in EMA’s 5-year analysis of the PRIME scheme [16]. Between 1 January 2018 and 30 June 2021 18 drugs that previously received the PRIME designation have been authorised (10 of them received a conditional Marketing Authorisation). Overall, 25% of PRIME eligibility applications are accepted, the therapeutic area of haematology was highlighted as having a success rate of 57%. Based on their experience and feedback from an industry-led survey EMA recommends enhancements in scope and timing of eligibility, flexibility of scientific advice and knowledge building to support the marketing authorisation. An important conclusion is that due to the considerable resource assessment, it is critical to select the drugs that are most likely to benefit.

Impact of Expedited Development Tools on Overall Development Timelines

In general, it is hard to quantify the overall impact of expedited pathways on the development timelines for pharmaceuticals as many other factors are involved. Several authors have attempted such analyses, but the results are difficult to interpret.

A study from 2009 [19] evaluated 51 new medical entities for oncology indications that had been approved by FDA in the period 1995 (upon introduction of Accelerated Approval) to 2008 (prior to the availability of BTD). This included 19 (37%) drugs with Accelerated Approval designation and 32 (63%) drugs that underwent regular approval. The median development time for both pathways of drugs was essentially the same (7.3 versus 7.2 years). Shea et al. focussed on BTD and compared cancer drugs with and without BTD for 29 drugs approved by FDA between 2013 and 2015 [20]. Drugs with BTD (12/29; 41%) reached the market faster than those without (17/29; 59%). This was mainly due to reduced development timelines as median time from submission of an investigational new drug application (IND) to submission of a new drug application (NDA) or biologics license application (BLA) was 2.2 years shorter. In addition, more drugs with BTD (8/12, 67%) were approved based on data from Phase 1 or Phase 2 trials only (compared to 4/17, 24% for non BTD drugs), as also shown by wide range in the development time for new oncology drugs of 4.0–9.6 years [19,20,21].

Liberti et al. found that the impact on overall development times (calculated as time from IND date to dossier submission) of drugs using any expedited pathway in the US depends on the exact routing that is followed [21]. They reported the shortest median development time of 1458 days for those drugs with accelerated approval, priority review and breakthrough designation. Products that benefited from fast-track designation or priority review alone had the longest development timelines (median of 2620 and 3515 days, which is longer than the median 2148 days for drugs not benefiting from any expedited pathway. The authors suggest that it would be worthwhile to explore the underlying factors that influence development. Such knowledge could also allow to better predict the impact of the expedited pathways and could play a role in rationalising their use and economise resources.

Impact on Review and Approval Timelines

Studies that analysed the impact of Priority Review on marketing application review times [21, 22] concluded that median review time for drugs using priority review or other expedited pathways (in US and Canada over various time periods) was substantially reduced. Combinations of more than one expedited pathways reduced review times by more than half [21]. The fastest combinations were Fast Track Designation + Accelerated Approval + Priority Review + BTD, with a median approval time of 145 days and Accelerated Approval + Priority Review + BTD, with a median approval time of 166 days (compared to 242 days and 365 days for drugs with priority review alone and standard review respectively). For drugs using any of these pathways the acceleration was on average four months (median of 243 days compared to 365 days standard review). From this perspective it is interesting to note that Wang et al. [23] showed that between 2011 and 2020 only 14 out of 410 new medical entities approved by FDA were granted all four expedited pathway designations and that 12 of them were oncology drugs.

Similarly, an analysis of all centrally authorised drugs in the EU revealed that the mean time for drugs reviewed under Accelerated Assessment was 248 days compared to 431 days for standard assessment in the EU during the 5-year period 2016–2020 (reduction of review time by 42%) [15]. The 5-year analysis of PRIME concluded that PRIME had a positive impact, reducing overall time to marketing authorisation, mainly due to a shorter clock-stop duration [16].

An important observation from above analyses is that “combined benefits” have been shown to have the largest impact on both development and review timelines. However, even though applying different expedited pathways simultaneously is quite frequently seen, this is rarely officially offered by the agencies. The only official procedure is pioneering drug designation (Sakigake) in Japan, providing close Agency interactions and accelerated approval timelines. In China, candidates for BTD are also eligible for priority review and possible rolling submission. Agency interaction and accelerated approval timelines are also foreseen for PRIME (which is essentially built as a procedure using close interaction for specific drugs to allow for accelerated assessment), but for drugs under PRIME, eligibility for accelerated assessment still needs to be confirmed.

The EU adaptive pathway approach, which ran as a pilot project under the Innovative Medicines Initiative between 2014 and 2018, provided such an end-to-end approach but is no longer pursued. During multi-stakeholder activities many concerns with an adaptive licensing approach were addressed but some gaps regarding pricing, reimbursement, interpretability of real-world evidence and also intellectual property questions remained.

Given the positive impact observed on development and approval timelines, an end-to-end holistic approach across ICH regulators would be the ideal way forward.

Approvals Based on Based on Early Evidence Data Packages

With approvals based on early evidence (e.g., surrogate endpoints, small or selective groups of patients) data packages, there is a higher amount of uncertainty at the time of approval, which is usually outweighed by the expected benefit to patients but requires post-authorization evidence for confirmation. A particular challenge arises from the scenario that the required post-authorisation studies may not support the benefit/risk balance in the conditionally approved indication at all, or only support benefit/risk in a specific patient subset [24]. In such a scenario, regulators will consider, based on the review of the totality of data available at this timepoint, whether the conditional or accelerated approval has to be revoked and the drug taken off the market, or the period for post-approval data collection should be extended or the indication should be restricted to the population with a positive benefit/risk balance. A prominent example in the EU is the revocation of the conditional marketing authorisation for lartruvo (olaratumab) in combination with doxorubicin for the treatment of patients with soft tissue cancer following review of data from the ANNOUNCE study revealing no survival benefit gain versus doxorubicin monotherapy [25]. In the US, between 1992 and 2021, approximately 165 oncology drugs have received accelerated approval. Of those, 69 have been converted to full approval. A total of 10 approvals were withdrawn because the initially anticipated benefit could not be confirmed. The main reasons were less than expected efficacy in the confirmatory trials and/or a changing unmet medical need landscape with efficacious alternative substitutes having become available [26].

The limited validity of the initial conditional marketing authorisation (1–2 years), either by law (Australia, EU, UK and Switzerland) or through planned drafted re-assessment of the authorisation after the confirmatory trials have been finalized (as in US) alongside with an agreed timetable aims to facilitate timely completion of confirmatory clinical studies and keeps pressure on sponsors after approval. In the US, as part of the next 5-year reauthorisation cycle of user fees discussion, drafts are ongoing (not final yet) to amend the accelerated approval pathway to (1) require FDA to agree on the conditions for the required confirmatory study for a drug approved under the accelerated approval pathway by the time the accelerated approval is granted and (2) “streamline” the administrative process for withdrawing an accelerated approval when the sponsor fails to perform due diligence in completing the confirmatory study or when the post approval trial has failed to confirm clinical benefit.

Potential Impact on Sequence of Submissions

The increasing availability of expedited pathways across the world is likely to have an impact on the regulatory submission sequence and launch strategy of drug developers. In future, first wave submissions might no longer start with US/EU but utilize the option of collaborative review such as Orbis/ Access as first wave. Considering the ongoing rapid rehaul of the Chinese regulatory system and depending on commercial considerations, China might in the future be considered as first wave country.

Although the availability of new, expedited regulatory pathways is welcomed, there are also challenges. An important challenge is that not all pathways are equally accessible and used. For example, in China the program is not open for drugs approved already outside China and developers face difficulties in acceptance of clinical data generated outside China. To maintain Japanese pioneering drug designation (Sakigake), first submission must occur in Japan or in parallel to another country. This could be overcome by involving China and Japan in clinical trials earlier in development. The implementation of the ICH guideline E17 on general principles for planning and design of multi-regional clinical trials is crucial in all ICH countries including China to increase the acceptance of applications with foreign clinical data. The Japanese pioneering drug designation (Sakigake), although well-valued, is very much Japan focussed and lacks the global outlook. In general, regional differences in scope and requirements will become a more important aspect of the global submission strategies.

International Collaborations

Forward-looking, in addition to further expanding on existing expedited regulatory pathways, regulatory agencies are looking increasingly toward collaboration pathways to share expertise and optimize resources. These pathways rely on work-sharing, collaborative review, exchange of expertise and/or shared assessment aids and technology. Currently active examples are Orbis, Access and ASEAN JACG and most recently the EU OPEN initiative (thus far restricted tor COVID vaccines and therapeutics). These initiatives are expanding and maturing as more countries join and experience increases.

For regulatory agencies, advantages include efficient use of resources through work-sharing, mutual learning and the possibility to strengthen expertise in a certain area as well as increase of global alignment, while maintaining independence in decision-making. Participation in these programs by pharmaceutical companies necessitates early planning of the sequence of submission, frequently frontloading of work and taking into account the regulatory and scientific guidelines of the major markets. Although this initially may complicate development (working with many different, sometimes contradictory guidelines, short response timelines), increasing collaboration between regulators may also trigger further harmonisation in regulatory requirements. Furthermore, the submitted dossiers will be increasingly similar and ideally, a consolidated list of questions will facilitate a smoother response process for developers.

Conclusions

Over the past years, a tendency has been seen for ICH members and beyond to modernize their regulatory systems to implement different expedited regulatory tools to ensure faster development and approval of innovative drugs in areas of unmet medical need. This has already resulted in new regulatory paradigms in major markets like China (providing BTD, priority review and conditional approval) and Brazil (now accepting less than comprehensive dossiers for rare diseases or diseases with unmet medical needs). MHRA by participating in the Project Orbis and Access Consortium as well as by establishing other innovative regulatory tools is able to approve certain medicines ahead of the European Union.

Despite the differences seen in all expedited approval pathways in ICH member states and regions they share a common denominator and are foreseen for drugs addressing an unmet medical need.

It is expected that additional regulatory acceleration options will arise in the near future, by further increasing collaborative work-sharing such as already implemented in the Access consortium and Orbis, building on existing pathways and revision of existing tools. In addition, new knowledge in science, new approaches to regulatory review taking advantage of digitalization such as dynamic regulatory assessment [27] may facilitate further reduction of regulatory review timelines while maintaining a scientifically robust regulatory assessment.

The changing regulatory environment will require sponsors to rethink drug development and regulatory strategy and may cause a transformative disruption to the current sequence of regulatory submissions, favouring those countries/collaborations that are best equipped to make innovative drugs for areas of unmet medical need available to patients in the shortest time frame.

Data Availability

All data and datasets analysed and described in this article are publicly available.

References

Wouters OJ, McKee M, Luyten J. Estimated research and development investment needed to bring a new medicine to market, 2009–2018. JAMA. 2020;323(9):844–53. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.1166.

Wong CH, Siah KW, Lo AW. Estimation of clinical trial success rates and related parameters. Biostatistics. 2019;20(2):273–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/biostatistics/kxx069.

Roberts TG, Chabner BA. Beyond fast track for drug approvals. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(5):501–5.

US, Food and Drug Administration. Project Orbis. https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/oncology-center-excellence/project-orbis. Accessed 23 June 2022.

Swissmedic Guidance document. Project Orbis HMV4. Version 3.

MHRA website. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/guidance-on-project-orbis.

Health Canada website. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/international-activities/project-orbis.html.

TGA website: https://www.tga.gov.au/project-orbis.

ANVISA website. https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/assuntos/noticias-anvisa/2020/anvisa-agora-e-parceira-do-projeto-orbis.

de Claro AR, Spillman D, Hotaki LT, et al. Project orbis: global collaborative review program. Clin Cancer Res. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-3292.

Australia-Canada-Singapore-Switzerland-United Kingdom (Access) Consortium. https://www.tga.gov.au/australia-canada-singapore-switzerland-united-kingdom-access-consortium. Accessed 2 January 2022.

Pharma to Market. Newsletter 22 July 2021. Access consortium releases strategic plan for 2021–2024. https://www.pharmatomarket.com/access-consortium-releases-strategic-plan-for-2021-2024/

Ahmad R, Chanprapaph T, Azatyan S, et al. Joint assessment of marketing authorization applications: cooperation among ASEAN drug regulatory authorities. In DIA global forum. Driving insights to action. Sept 2021. https://globalforum.diaglobal.org/issue/september-2021/joint-assessment-of-marketing-authorization-applications-cooperation-among-asean-drug-regulatory-authorities/

8th EMA stakeholder platform meeting on Centralized Procedure. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/events/eighth-meeting-industry-stakeholder-platform-operation-centralised-procedure-human-medicine

CIRS R&D briefing 85. New drug approvals in six major authorities 2012–2021: focus on facilitated regulatory pathways and internationalisation. https://www.cirsci.org/publications/cirs-rd-briefing-85-new-drug-approvals-in-six-major-authorities-2012-2021/

European Medicines Agency. PRIME: analysis of the first 5 years’ experience. Findings, learnings and recommendations. EMA/587035/2021, 2022. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/report/prime-analysis-first-5-years-experience_en.pdf

European Medicines Agency. Accelerating Patients’ access to medicines that address unmet medical needs. Updated review of the accelerated assessment tool. Slide deck presented by Victoria Palmi & Caroline Pothet—EMA2021. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/presentation/presentation-accelerating-patients-access-medicines-address-unmet-medical-needs-vpalmi-cpothet-ema_en.pdf

Bujar M, McAuslane N, Liberti L. The qualitative value of facilitated regulatory pathways in Europe, USA and Japan: benefits, barriers to utilization and suggested solutions. Pharmaceutical Medicine, 2021. https://cirsci.org/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2021/02/Bujar2021_QualitativeValueofFRPs.pdf Accessed 4 August 2022.

Richey EA, Lyons EA, Nebeker JR, et al. Accelerated approval of cancer drugs: improved access to therapeutic breakthrough or early release of unsafe and ineffective drugs. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(26):4398–405.

Shea M, Ostermann L, Hohman R, et al. Regulatory watch: impact of breakthrough therapy designation on cancer drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15(3):152.

Liberti L, Bujar M, Breckenridge A, et al. FDA facilitated regulatory pathways: visualizing their characteristics, development, and authorisation timelines. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:161.

Downing NS, Aminawung JA, Shah ND, et al. Regulatory review of novel therapeutics—comparison of three regulatory agencies. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(24):2284–93.

Wang S, Yang Q, Denk L, et al. An overview of cancer drugs approved through expedited approval programs and orphan medicine designation globally between 2011 and 2020. Drug Discov Today. 2022;27(5):1236–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2021.12.021.

Prasad V, Mailankody S. The accelerated approval of oncologic drugs: lessons from ponatinib. J Am Med Assoc. 2014;311(4):353–4.

EMA/254126/2019. Procedure under Article 20 of regulation (EC) no 726/2004. Assessment report Lartruvo procedure number: EMEA/H/A-20/1479/C/4216/015. 25 April 2019

Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Final summary minutes of the oncologic drugs advisory committee meeting 27–29 April 2021.

Nogueira F. The accumulus synergy consortium. White paper. https://www.accumulus.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Accumulus_Synergy_White_Paper.pdf.

TGA provisional determination eligibility criteria, version 1.2, August 2021. Accessed 18 May 2022

Ministry of Health-MS. National Health Surveillance Agency—ANVISA. Resolution of the Collegiate Board—RDC 205 of December 28, 2017.

Health Canada guidance document, notice of compliance with conditions (NOC/c). 16 September 2016.

State administration for market regulation. SAMR order No. 27, measures for the administration of drug registration. 22 January 2022.

CDE notification No.2020/41: technical guidance on conditional approval of drugs (interim), 19 November 2020.

Commission Regulation (EC) No 507/2006 of 29 March 2006 on the conditional marketing authorisation for medicinal products for human use falling within the scope of Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council.

EMA/CHMP/509951/2006, Rev.1. Guideline on the scientific application and the practical arrangements necessary to implement Commission Regulation (EC) No 507/2006 on the conditional marketing authorisation for medicinal products for human use falling within the scope of Regulation (EC) No 726/2004.

Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 March 2004.

Directive 2001/83/EC of the European parliament and of the council of 6 November 2001 Annex I, Part II, 6.

EMEA/357981/2005. Guideline on procedures for the granting of a marketing authorisation under exceptional circumstances, pursuant to Article 14 (8) of regulation (EC) No 726/2004.

MHLW Notification: PSEHB/PED No. 0831/1, PSEHB/MDED No. 0831/1: handling of priority reviews, 31 August 2020.

MHLW notification: PSEHB/PED No. 0831/2: handling of conditional approval for pharmaceutical products, 31 August 2020.

MFDS notification No. 2021–90: regulation on item license, declaration and review of pharmaceutical drugs, 11 November 2021.

Ordinance on licensing in the medicinal products sector. Medicinal products licensing ordinance, MPLO; SR 812.212.1.

Swissmedic. Guideline temporary authorisation of use of an unauthorised medicinal product version 4.0.

MOHW Letter No.1081410835: Issuance of accreditation. Keypoints of drugs for pediatric population or rare diseases, simplified review mechanism for new drugs registration, prioritized review mechanism for new drugs registration, accelerated review mechanism for new drugs registration and accreditation keypoints of breakthrough treatment drugs, 18 November 2019.

Guidance for Great Britain conditional marketing authorisation applications. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/conditional-marketing-authorisations-exceptional-circumstances-marketing-authorisations-and-national-scientific-advice. Accessed 23 June 2022.

The human medicines regulations 2012. Conditions of UK marketing authorisation: exceptional circumstances. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2012/1916/regulation/60. Accessed 23 June 2022.

Guidance for Great Britain Marketing authorisations under exceptional circumstances. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/conditional-marketing-authorisations-exceptional-circumstances-marketing-authorisations-and-national-scientific-advice#guidance-for-great-britain-marketing-authorisations-under-exceptional-circumstances. Accessed 23 June 2022.

FDA Guidance for Industry. Expedited programs for serious conditions—drugs and biologics. May 2014.

State administration for market regulation. measures for the administration of drug registration. SAMR Order No. 27. 15 January 2022.

EMA website. PRIME: priority medicines. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/research-development/prime-priority-medicines. Accessed 23 June 2022.

MHLW Notification: PSEHB/PED No. 0831/6: handling of designation of pioneer drugs, 31 August 2020

Kondo H, Hata T, Ito K, et al. The current status of Sakigake designation in Japan, PRIME in the European Union, and breakthrough therapy designation in the United States. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2017;51(1):51–4.

Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Guidance. innovative licensing and access pathway. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/innovative-licensing-and-access-pathway. Accessed 23 June 2022.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Food and Drug Administration. Expedited programs for regenerative medicine therapies for serious conditions. Guidance for Industry, February 2019.

EMA/276376/2016. Final report on the adaptive pathways pilot. 28 July 2016.

TGA priority determination eligibility criteria, version 1.3, Apr 2021. Accessed 18 May 2022.

TGA priority determination: A step-by-step guide for prescription medicines, version 1.1, Aug 2018. Accessed 18 May 2022.

Ministry of Health-MS. National Health Surveillance Agency—ANVISA. Resolution of the Collegiate Board RDC 204 of 27 December 2017.

Health Canada Policy Priority Review of Drug Submissions. Effective date 1 March 2006.

Health Canada Guidance for Industry. Priority review of drug submissions. Effective date 1 March 2006.

Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council. Recital 33 and Article 14(9).

EMA/CHMP/671361/2015 Rev. 1. Guideline on the scientific application and the practical arrangements necessary to implement the procedure for accelerated assessment pursuant to Article 14(9) of Regulation (EC) No 726/2004. 2016.

The Pharmaceutical and Medical Device Act (Act No. 145 of 1960) as amended by the Act for Partial Revision of the Pharmaceutical and Medical Device Act (Act No. 63 of 2019).

MFDS Notification No. 2021–29: provision on approval and review of biological products. 5 April 2021.

MFDS/MaPP: 5200.52B: procedures for the quick approval and examination of biologics for infectious disease pandemic. June 2020.

Guide-0880–02: guidelines for the application of expedited review of pharmaceutical drugs. September 2021.

Guide-1064–01: considerations when applying for designation for expedited review of medical products. 31 May 2021.

Instructions-0983–02: procedure for expedited review. 31 March 2021

Health science authority therapeutic products guidance on therapeutic product registration in Singapore, TPB-GN-005–009, April 2022. Accessed 21 June 2022.

Swissmedic guidance document Fast-track authorisation procedure HMV4 ZL104_00_002e / V7.0, 01.07.2021.

Swissmedic guidance document procedure with prior notification HMV4 ZL101_00_013e / V3.2, 01.03.2021.

MHRA Guidance. Rolling review for marketing authorisation applications. 31 December 2020. Rolling review for marketing authorisation applications—GOV.UK (www.gov.uk). Accessed 23 June 2022.

PDUFA Reauthorization performance goals and procedures fiscal years 2023 through 2027.

Funding

The research for and writing of this article were conducted and funded by Merck KGaA/EMD Serono. All authors are employed by Merck KGaA. We would like to greatly acknowledge our Merck and EMD Serono local regulatory colleagues in the discussed countries who supported this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PF, MUK, CH and RJ contributed to the conception of the work, collection of the information, the drafting, reviewing and revision of the article. ERL (US) and CH (EU) were involved in the review and final approval of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All contributing authors are employed by Merck KGaA/EMD Serono, a pharmaceutical company with a strong presence in oncology medicines.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Franco, P., Jain, R., Rosenkrands-Lange, E. et al. Regulatory Pathways Supporting Expedited Drug Development and Approval in ICH Member Countries. Ther Innov Regul Sci 57, 484–514 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43441-022-00480-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43441-022-00480-3