Abstract

Compared to other developing regions, Africa has experienced a relatively late start to the demographic transition, although certain countries in the continent’s north and south did. As a result, Africa is only now starting to broadly benefit from the demographic dividend. Thus, a study on the drivers of the dividend, the timing and length of the dividend, and the dividend optimization strategies is crucial. The paper uses a cross-country panel data for 34 African countries for the years between 1990 and 2018. To identify the drivers of the demographic dividend, fixed effects econometric analysis is used. The foremost contribution of the paper is that it empirically shows the ongoing demographic transition and the simulated time span of the potential first and second demographic dividends. It also identifies pertinent drivers of the demographic dividend. Besides, as a new conceptual framework, it introduces an innovative analytical framework for augmenting the demographic dividend from formal migration. The framework is named after the “International Surplus Labour Circulation (ISLC) model.”

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Background

Compared to other developing regions, Africa has experienced a relatively late start to the demographic transition, although certain countries in the continent’s north and south did. As a result, Africa is only now starting to benefit from the demographic dividend. For instance, compared to the previous decades, in the post 1990 decades, Africa has been in the midst of a remarkable change in population age structure. The transition towards a higher share of youth and labour force in the total population has profound policy implications. For example, the timing of the transition varies among countries. As the causes of the transition vary across the nations, the consequences may also vary, mainly due to, among other differences, the quality of governance with respect to job creation, population control, and human capital creation (Bloom and Williamson 1998; Mason 2002; Bloom et al. 2003; Mason and Lee 2007; Mason et al. 2017).

In demographic dividend related studies, the role of migration is blurred, whereas it is a crucial factor to consider in the African context. In this context, to understand the causes and effects of international migration, the notion of “new institutional economics” is helpful. For instance, Acemoglu et al. (2005 p. 402) claim that “institutions are the fundamental cause of differences in economic development.” By implication, the quality of institutions is responsible for brain drain and the flight of human resources (Obeng-Odoom 2021). This is of course in line with Rodrik et al. (2004), who claim that “the quality of institutions trumps everything else.” However, the economic effect of immigration on the destination countries is often highly politicized. For instance, Obeng-Odoom (2021) claims that the migration crisis is the result of a political-economic system, particularly unfair rent collection by the privileged few who use “institutions such as land and property rights, race, ethnicity, class, and gender to keep the poor in their status quo.”

The mainstream debate on how the human population affects development has been sparked by the question of whether it is an advantage or a liability. However, the age distribution is currently the subject of more curiosity than the general population (Bloom and Williamson 1998; Mason 2002; Bloom et al. 2003; Mason and Lee 2007; Mason et al. 2017). In Africa, the currently undergoing fast demographic transition is boosting the youth cohort and labour force, which may unlock a new window of opportunity to harness a “demographic dividend”.Footnote 1 The demographic transition per se cannot, however, ensure the dividend because conducive policies and governance institutions are crucial. This is mainly because, in the absence of favorable policies and institutions, the bulging youth and the labour force may even result in a curse which is called the “demographic bomb”.Footnote 2 The curse may manifest as eruption of conflicts (Woldegiorgis 2022a, b). Therefore, the two razor-sharp swords of the demographic shift are generating a great deal of excitement among public policymakers. For example, the African Union (2017, 2) underscores that there is an “[…] urgent necessity to transform the potential of Africa’s large youth population, often referred to as the youth bulge, into a demographic dividend.”Footnote 3

Conversely, there is mounting apprehension in high-income countries about their shrinking populations, especially the active labour force. The support ratio is irreversibly deteriorating in high-income countries, if not all, due to aging and the replacement of the “baby boom” by the “baby bust.” As a result, the shrinking labour force in developed regions and the growing labour force in developing countries need to be comprehended in a holistic approach to mutually harness the demographic dividend and facilitate brain circulation instead of brain drain or unfair brain gain. Apparently, there is a high influx of an unregulated labour force into labour shortage regions. However, the spontaneous transaction of migrants is giving rise to a new “lucrative illicit smokeless industry” called human trafficking. Thus, the intra-African and inter-continental influx of risky illegal labour force movements caused by economic reasons and political upheavals necessitates more strategic thinking to deal with brain-gain and brain-drain in the pursuit of the demographic dividend. Although there is a plethora of literature on simulations of the demographic dividend, they do not effectively address the issue of optimal use of the youth and labour force bulge globally. Otherwise, the demographic transition per se may not guarantee a dividend in developing countries. It may even be a curse. This instigated the current paper.

Hence, the paper is organized as follows. In the second section, literature and the conceptual framework of the examination are elucidated. Section 3 presents data sources and methods of scrutiny. After discussing the statistical results in the fourth section, the final part focuses on the public policy implications.

1.1 Aims and research questions

The paper exclusively aims to elucidate the demographic transition, when the window of opportunity to dividend opens and closes, and to identify some of the drivers of the demographic dividend. Besides, it aims to introduce an innovative analytical framework for augmenting the demographic dividend from the wasting labour force due to unregulated, risky emigration. The framework is named after the “International Surplus Labour Circulation (ISLC) model.”

The research questions are: Is there a meaningful demographic transition in Africa compared to the rest of the economic regions? What are the drivers of the dividend? What is the time span of the potential dividend? How can the dividend “potential” be realized and optimized through a well-regulated labour circulation? What are the public policy takeaways in the pursuit of harnessing a demographic dividend?

1.2 Worth and limitation

The paper may contribute to the demographic dividend policy discourse in three ways. (i) It describes the ongoing demographic transition in Africa and estimates the life span of the first demographic dividend from a comparative perspective. (ii) The available literature does not seemingly give much attention to the role of formal emigration from the place of surplus to the place of shortage as a strategy for optimization of the dividend. Therefore, this paper builds on the Lewis dual economy model to show a brand new analytical framework. (iii) The focus of the literature on demographic dividend is dominated by its role in the transition to economic growth, but this paper extends its role to inclusive development as well. However, it is crucial to keep in mind that the continental demographic variables are forecasted under ceteris paribus assumptions. Therefore, the scrutiny in the paper cannot substitute for a country-specific, detailed analysis.

2 Literature

2.1 Theory

Regarding the population’s contribution to economic growth, there are opposing points of view. Malthusian demographic theory holds that “food” grows arithmetically, while population grows geometrically, leading to a “Malthusian trap” or “Malthusian catastrophe” that calls for a “positive check” like contraceptive pills as a family planning strategy. According to Seltzer (2002), Ehrlich (1968) subsequently explains the idea of a “population bomb” hypothesis. Ehrlich predicted the global famine that took place between the 1970s and 1980s because of the apparent overpopulation in 1968. The net result of population growth on economic growth, according to the United Nations (1973), would be “undesirable.”

Indeed, population growth and modernization manifested by urbanization and industrialization have come up with more concerns from a climate change, environmental pollution, and unbalanced growth point of view (Obeng-Odoom 2022). For instance, Boulding (1956) in his “theories of evolutionary economics and organizational change” clearly prophesies about the imminent threats in this regard. He analyzed the interface of ecological change and civilizational change. In other words, he underscores the precarious relationship between civilizational complexity and sustainability. He not only foresees the threat of climate change and other ecological hurdles but also ethical decay (Boulding 1984) and forthcoming distributional injustice (Boulding 1992).

The other argument is the feminist perspective on population and ecology. For instance, according to Lammensalo (2021), there are divided thoughts with respect to reducing human pressure on the “earth systems.” Some claim that reducing the population is the foremost remedy. Conversely, feminists claim that the human rights of vulnerable individuals and communities should not be compromised by neoliberal population control policies (ibid.). Gil-Vasquez and Elsner (2022, p. 1) are also in line with the argument. They claim: oligopolistic and oligarchic structures, plutocracy, austerity in neoliberal regimes, and financialization are leading to long-run economic slack, mass unemployment, and a human surplus and waste. Based on a postcolonial feminist theoretical framework, Lammensalo (2021) underscores that to recoup the neo-colonial practices and structural inequalities that shape intersections between demographic issues including sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) and climate change, it is important to adhere to postcolonial feminism, which recognizes power inequalities in promoting more justice-based approaches to sustainability.

Population optimist theories claim that rapid population growth and large population sizes can promote economic prosperity by supplying copious labour, intellectual capital, economies of scale, and knowledge spill over (Kuznets 1960; Boserup 1965). The third view is called the population neutralist theory, which debatably underscores that population growth alone has little impact on economic performance (Bloom and Freeman 1986; Kelley 2001 as cited in Bloom et al. 2003).

Meanwhile, the current paper recent demographers and economists who claim that instead of focusing on pessimistic, optimist, or neutralist theories, it is quite meritorious to zoom into the age structure and the dynamics because people in all age groups are not equally productive (see Bloom and Williamson 1998; Mason 2002; Bloom et al. 2003; Mason and Lee 2007; Mason et al. 2017).

2.2 Empirics in literature

The empirical analyses show that a change in the age structure of a population has only a transitional effect. For instance, the change in the age structure backed by inclusive public policies in East Asia contributed one-third of economic growth, which is often called an “economic miracle,” as the working age population grew much faster than its dependent counterpart between 1965 and 1990 (Bloom et al. 2003; Mason et al. 2017). Lee and Mason (2007) claim that the crucial point is not only the age structure but also inclusive public policy institutions. Conversely, they also underscore that there are other parts of Asia where the demographic transition has not resulted in a demographic dividend due to the prevailing extractive institutions. Consequently, the demographic transition even suppressed economic growth (ibid.).

However, the interface between population, economic growth, and institutions is not always straightforward in Africa. For instance, Bloom et al. (2007) stated that there are some sub-Saharan African countries, such as Uganda and Mali, that showed high economic growth rates due to “excellent” policy reforms, despite negative growth in the share of the working age population, whereas the economic growth projections of South Africa and Botswana, which were the then regional leaders in terms of “quality in the political institutions,” the demographic dividend was projected to be trivial in the following two decades (ibid.).

Regarding the pace of demographic transition and institutionalism, the statistical findings of Dramani and Oga (2017) and May and Guengant (2020) show that in recent decades, support ratios have been growing swiftly in Africa. For instance, May and Guengant (2020) claim that about 35 years later than in the other less developed countries, high mortality and fertility levels have started to decline in the 48 countries of sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). They emphasize that to capitalize on the demographic dividend, countries have to create economic opportunities for young adults and invest in human and physical capital. Ssebbaale and Kibukamusoke (2016) also argue that most African countries are experiencing a fast demographic transition. However, there are countries that still have high fertility rates, which may have adverse effects on realizing the potential demographic dividend. They noted that there are countries that face governance bottlenecks such as low accountability by public officials and the rule of law that may be unpromising for the potential demographic dividend. Bloom et al. (2017) state that Africa has substantial potential to harness a demographic dividend. Realizing the time and magnitude, however, is dependent on policies and institutions in critical areas such as macroeconomic management, human capital, trade, governance, and labour and capital markets. In demographic dividend studies, the waste of labour force due to illegal migration has not got enough attention. Thus, the following innovative framework may provoke discourse in the area.

2.3 Introducing a new conceptual framework: ISLC model as game strategy for demographic dividend optimization

Obviously, mobility labour force among economic sectors and geographical areas is an important factor in harnessing or wasting a demographic dividend potential. Institutional political economists such as Harold Innis and Albert Hirschman, for example, have articulated the relevance of forward and backward linkages among sectors. According to the notion, industry can benefit from input from the rural agriculture sector, which is called “forward linkage.” Likewise, agriculture should benefit from industrial products such as fertilizers, pesticides, and machinery that are used as inputs for agriculture. This is called backward linkage. Accordingly, the cheap labour force in the rural area could be efficiently used in industry and surge profit. Consequently, the rural sector can also benefit from the low prices of industrial products as a result of modern production efficiency. Lewis (1954) proposes a conceptual framework for understanding the economic incentive of labour circulation in a dual-economy model, namely, the traditional agriculture and modern industry sectors.

However, the duality neglects another crucial sector, which in this paper is generalized as the “international modern sector.” The sector is accommodating a lot of migrated labour force including from Africa. The labour-sending countries are also benefiting from remittance, among other things. The poor infrastructure in the 1950s may have confined to only a dual sectoral mobility of labourers. Given the other push and pull factors, advancements in information and communication technology and transportation infrastructure nowadays allow people to move not only from rural to urban areas within the same country but also across borders. This is so for two reasons. On one side, the local modern industrial sector cannot endlessly absorb labourers that move from rural areas. The most important pull factor, however, is the wage disparity between the destination and labour-sending countries. The Lewis dual-sector model does not address this issue, although it is crucial.

Regarding the feebleness of the dual economic sector and surplus labour hypothesis of Lewis, Molero-Simarro (2016) brings evidence from the Chinese economy’s recent development trajectory, which claims that increasing income inequality has caused urban poverty in China. In cities, the rich have gotten richer while the poor have gotten poorer. Accordingly, the wage differential between the modern industry sector and the traditional agriculture sector has significantly declined. As a result, rural–urban migration has also significantly declined, which is “proof of the Lewis model's turning point.” Thus, the following section is devoted to introducing a new conceptual framework that builds on the Lewis dual-sector development model. The new framework is named after the international surplus labour circulation (ISLC) model.

From a policy and institutionalism point of view, the ISLC model is significant because it may provoke conversation and recraft policies regarding brain drain and illegal labour mobility to the third sector. The model is significant in terms of provoking pragmatic debate about formalizing labour exchange between sending and receiving countries, thereby optimizing the potential demographic divided among labour-sending and -receiving countries.

To introduce the initial model, in the year 1954, Sir Arthur Lewis published a research paper entitled “Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour.” The assumptions in his model are that (i) traditional agrarian society has a surplus or “disguised” labour; (ii) there is a shortage of workers in the modern sector where higher wages are offered and there is absorptive capacity for migrated surplus labour force from the traditional agriculture sector; (iii) wages are flexible in the modern sector; (iv) the modern sector can be profitable due to the cheaper new labour force; and (v) the profit will be reinvested in the business in the form of fixed capital, which is vital for dividends and thereby development. Accordingly, the model appreciates labour circulation as an instrument to ensure structural change from traditional agriculture to modern industrialization (Lewis 1954). The current paper introduces “international modern sector” (see the left column of Fig. 1).

International surplus labour circulation (ISLC) model. Source: Sketched by the author based on the Dual Economy Model of Lewis (1954)

Although the concepts of “unlimited supply” and “disguised unemployment” are seemingly contentious, it is obvious that in overpopulated rural areas, including Africa, there is a high unemployment and underemployment rate. According to Lewis (Molero-Simarro 2016), the local modern industrial sector in the countries does not always have an infinite labour absorptive capacity. According to the conventional infant industry argument, it has a limited absorptive capacity for disguised labour. However, the model could be extended to include a second modern “sector” in low-fertility developed countries so that labourers would have three alternative choices: stay in the subsistence local traditional sector, move to the local modern sector, or look for opportunity in labour-scarce developed regions abroad, ceteris paribus.

Figure 1 shows that when a foreign modern sector is introduced as a third sector in the Lewis dual economy model, the surplus labour can be legally circulated (moved) into labour-deficient regions, where the previous surplus labour can find employment opportunities with a potentially higher wage rate compared to the surplus labour-sending sector or region. In return, the labour-sending sector and region can benefit from remittances and reinvestment as a payoff. Cheap circulated labour can also benefit the labour-receiving region. The notion is that due to globalization, the supply and demand of labour are not limited to a dual economy like in the 1950s. Therefore, if the local modern sector is not labour-absorptive enough, relocation to the third “sector” is compelling in a globalized world. The best example is the American Diversity Immigrant Visa (DV lottery) program. As will be explained later, the agreement between decision-making agents in developing and developed regions can be modeled using game theory.

One may start the scrutiny from the right-side column of Fig. 1 (see the traditional sector column on the right). According to Lewis, developing countries have dual economies: (i) a local traditional agricultural sector and (ii) a local modern industrial sector. In the traditional agriculture sector, there are a million disguised (unlimited supply of unemployed) labourers who could be relocated to the modern sector without reducing total production in the traditional sector. The marginal product of surplus labour is zero in the traditional sector. As a result, wages are determined not based on a marginal product but on an average product. As shown in the middle column of the figure, the local modern sector in developing countries not only pays higher wages but also absorbs parcels of surplus labour relocated from the traditional sector. Moreover, the modern sector in developing countries is profitable due to the cheap and plentiful labour force (Lewis 1954). It is assumed that the local modern sector pays at least 30% more wages compared to the traditional sector. Thus, the profit will be reinvested, and more output will be produced sustainably (ibid.). Hence, industrialization could be fostered rather than relying on subsistence agriculture. This is how, through the Lewis model, a greater demographic dividend could be harnessed and structural change could be promoted.

Nevertheless, the Lewis model does not recognize that the modern sector has limited labour absorption capacity in developing countries. Moreover, it does not include the foreign sector in the model. In reality, however, the disguised unemployed and underemployed not only from the traditional agriculture sector but also from the local modern industry and service sectors may find employment opportunities in the modern sectors of a foreign country.

Developed countries obviously have a scarcity of labour due to the demographic downturn. The above premises lead to an important proposition. Part of the surplus labour in the traditional sector from developing regions can be formally absorbed into the local modern sector, and the rest can be absorbed by a foreign country. As a result, the traditional sector in a developing country may generate more demographic dividends from formally circulated labour in the form of remittances, business ideas, and technology transfer, among other things. According to Lewis, the local modern sector still has a plentiful and inexpensive labour supply. If conducive and competent public policies are in place, it can also benefit from increased demand for its products, capitalization, and investment in the local market over time, as demographic dividends beget more dividends. May facilitate the free movement of factors of production, particularly labour from developing regions and capital and technology from modern regions, in a formal and mutually beneficial way to harness the optimum demographic dividend sustainably, which could be termed “forward and backward linkage.”

As shown in Fig. 1, the model shows the following facts: Before circulation, APAt is greater than MPAt in the traditional sector. In the modern sector, wages are paid based on marginal product. The marginal product in the foreign modern sector is assumed to be greater than the marginal product in the local modern sector. If this is true, only then will the surplus labourers consider international labour relocation. The relocated labour, as shown in the bold curves on the top of the modern sectors in the figure, can produce a substantial product. As there is remittance, technology transfer, and investment in the traditional sector, productivity will also improve with the circulation of surplus labour. If the assumptions hold true, the additional dividend due to the increased circulation will generate more dividends in all sectors and will be reinvested. Accordingly, the circulation will cause structural change and result in more inclusive development everywhere.

2.4 Payoff matrix in the game theoretic ISLC model

Currently, there is no legal free mobility of labour in the international labour market because there are national boundaries and governments that decide on the modality of allowing the entry of international labourers. Therefore, the traditional sector (mostly represented by households and farmers’ associations) can negotiate with their governments on minimum wage increments in the country through an electoral political game. Furthermore, through multilateral and bilateral agreements, governments from developing regions can negotiate with governments from labour-deficit and low-fertility developed countries (Tables 1 and 2).

There is evidence to implicitly supplement the arguments in the ISLC Model. For example, according to the United Nations (2017/8), the developed regions as a whole will experience a shrinking of the population. That is why, since the 1990s, migration has been the primary source of population growth in the developed regions. The United Nations (2012) also states that “[w]hile there is no substitute for development, migration can be a positive force for development when supported by the right set of policies”.Footnote 4

It is clear that there is a moral hazard in the prevailing laissez-faire non-cooperative games in the circulating labour force. Currently, migration policies are devised from a humanitarian aid or moral philosophy point of view. However, according to the ISLC model, there is also an economic payoff (i.e., demographic dividend) for all parties from sharing disguised labour with the support of inclusive public policies.

2.5 Hypothesis

The structure of the population is the crucial driver of development (Gendreau 1991; Bloom and Williamson 1998; Lee et al. 2003). The transition may also trigger a political eruption, which is termed a ticking time bomb (Lin 2012; Ehrlich 1968; Coale and Hoover 1958; as cited in Bloom and Williamson 2007). The literature to date shows that in the presence of inclusive institutions, youth can positively contribute to their own development, which leads to the first hypothesis (Bloom and Williamson 1998; Acemoglu and Robinson 2016; North et al. 2009).

-

Hypothesis 1: The proportion of the youth population is important drivers of the demographic dividend and, as a result, of a society’s inclusiveness, but it is dependent on the quality of institutions.

The literature also shows that developing regions have surplus labour, whereas modern urban industrial areas face a shortage of labour (e.g., Lewis 1954), which leads to the second hypothesis.

-

Hypothesis 2: Formal transactions of surplus labour can increase the demographic dividend for the region of labour surplus and the region of labour deficiency.

3 Definitions of variables, data source, and method of analysis

3.1 Definition of variables and drivers of demographic dividend

Demographic dividend is often conceived as the change in per capita income (Bloom and Williamson 1998; Mason et al. 2017). However, considering only the economic dividend of demographic change might be conceptually ambiguous. For instance, a demographic bomb includes political instability. Demographic transitions also affect social investments and vice versa (Mason et al. 2017). Therefore, development variables might best describe the multidimensional dividend caused by the transition. Hence, in the panel regression, the inclusive development index (IDI) is used as a proxy for the demographic dividend. The details of the multidimensional index are explained in Woldegiorgis (2020a).

The youth bulge is proxied by the share of youth between 15 and 24 in the total population, whereas institutional quality is proxied by country policy and institutional assessment (CPIA).

3.2 Data source

This paper is entirely based on metadata from secondary sources. The demographic data, including the youth bulge, are derived from the United Nations’ 2019 World Population Prospects,Footnote 5 whereas labour income and consumption data are extracted from the national transfer accounts (NTA).Footnote 6 The metadata on remittance, institutional quality, and other controlled macroeconomic variables for the regression are extracted from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators and the International Labour Organization (ILO) database.

3.3 Methods of data analysis

Methods of data analysis vary based on the research questions. To verify if there is a substantial demographic transition in Africa, the conventional demographic transition model (DTM) and population pyramid are outlined. In the proposed international surplus labour circulation model (ISLC) model, the “Dual Economy Model” of Lewis is presented to show that formal surplus labour circulation across regions has a greater potential payoff, i.e., dividend. A mathematical model for estimating the first and second demographic dividends is also presented. However, the baseline data for labour income and consumption for different age groups is hardly available for Africa or individual countries. Therefore, the metadata for the potential dividends is extracted from NTA and described graphically. Finally, a panel data regression is also conducted to prove the statistical significance of the drivers of the demographic dividend. In the regression model, the inclusive development index is used as a proxy to capture both economic and non-economic effects of demographic transition.

3.4 Demographic dividend estimation model

According to May and Guengant (2020), there are three main formulations of the opening of the window of opportunity for the demographic dividend. The first is to consider that the window of opportunity opens when (i) the percentage of under 15 years old reaches 30% or below of the total population and (ii) those aged 65 and over remain below 15% of the total population. As of 2020, May and Guengant obtained different results based on the low and high variant projection data of the 2019 United Nations World Population Prospects. Accordingly, only five sub-Saharan African countries meet the two age conditions above. A second formulation is that the window of opportunity opens when the demographic dependency ratio (the number of people under 15 and over 65 divided by those aged 15–64) becomes equal to or less than 0.6.

May and Guengant (2020) found that six sub-Saharan African countries already have such a dependency ratio. The third formulation is that the window of demographic opportunity opens when the working-age population (15–64) is growing faster than the total population and especially than the young population (under 15) as a result of a decrease in the fertility rate. Because all Sub-Saharan African and North African countries have begun to experience fertility declines, the demographic window of opportunity in Africa remains open. The method used by May and Guengant (2020) has its own merits because it is not only simplistic but also helps comprehend the dividend in the absence of labour income and consumption data at different years of age. However, the cutting points are apparently subjective.

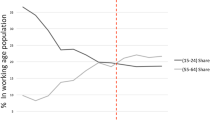

However, the current paper follows a different model of demographic dividend estimation. The model has gained prominence in the last two decades and has been consistently used (Bloom and Williamson 1998; Mason and Lee 2007; Mason and Kinugasa 2008; Lee and Mason 2010; Prskawetz and Sambt 2014; Mason et al. 2015, 2017). The model has its own merits and limitations. The merit is that it is subjectively free and enables one to calculate the first and second dividend potentials. It also enables us to clearly see when the window of hope opens and closes. When the slope of the economic support ratio starts to be positive, the window of opportunity opens. When the support ratio curve reaches its peak, at the same time, the wind of opportunity closes (see Figs. 2 and 3). The economic support ratio should not be confused with the conventional support ratio (i.e., ratio of active members to retirees) because the economic support ratio is about labour income and aggregate consumption at different years of age. That is why, the author prefers not to follow the thresholds of May and Guengant (2020). However, most of the African countries have not been documenting labour income and consumption at various years of age. Therefore, it is difficult to calculate the dividend, particularly the first demographic dividend. That is why, the paper uses secondary source (see Fig. 4).

For interested readers, the mathematical model is explained as follows. In an economic life cycle, people are assumed to live in three broad age groups: children, adults, and the elderly. Accordingly, the model illustrates the relationship between people of different ages, their labour income, and consumption overtime. On average, the young and the old consume in excess of what they produce through their labour, while people in the labour force age group produce more through their labour than they consume. Hence, the life cycle is simulated using two age profiles: labour income and consumption. The notion of support ratio is also helpful as it encompasses both the population age structure and country-specific age patterns of production and consumption in the life cycle (Mason et al. 2017, 5).The model being built is built on the following generic mathematical identity, where Yt is the total national income, Nt is the total population (consumer), and Lt is the labour force in time t. The support ratio, SR (t), is calculated as the ratio of the number of effective workers to the number of effective consumers:

From Eqs. 1 and 2, one can draw Eq. 3:

Equation 3 shows the direct relationship between the support ratio and per capita income.

The growth of per capita income due to increase in support ratio is called the first demographic dividend (ibid, p.7)

Therefore, to calculate the first demographic dividend, average labour income and consumption data are required in different age groups. For example, age could be grouped into age groups from 1 to 100+. The age is given in years.

The second demographic dividend is growth in per capita income due to \(\left(\frac{\partial Yt}{\partial Lt}\right)\) which could be put as a function of capital and total factor productivity in the Cobb Douglas production function (Mason et al. 2017, p. 5; Moreland et al. 2014, p. 10).

If we put all the variables in Eq. 1, we get

The first demographic dividend is virtuously caused by support ratio and policy, whereas the second demographic dividend is affected by many factors, including capital from saving, technology, and institutions. However, for simplicity, capital, especially social security funds, is often used to calculate the second demographic dividend (ibid). The notion is that as longevity increases, the demand for social security funds increases. Then, the fund is used as a source of capital and reinvested, which generates sustainable economic growth, i.e., the second demographic dividend. In sum, the first demographic dividend is caused by an increment in the working population relative to the non-working population, and it is a transitional one, which means it could be achieved for a limited period of time. The total demographic dividend (or simply demographic dividend) is the sum of the first and second demographic dividends.

4 Discussion of results

4.1 Demographic transition in Africa

Although the demographic transition in Africa was slow, since the 1990s, the transition has been swift (Fig. 5).

Since 1990, the natural growth rate of the population has been declining. This implies that the continent is currently in stage III of the demographic transition model (DTM). It passed through stage II swiftly (Figs. 6 and 7).

In comparison to other regions, Africa’s support ratio will be the highest by the year 2025. Its economic implications are vivacious. The high proportion of working-age people in a society can provide a window of hope for African countries to escape the poverty trap by creating a conducive institutional and policy environment.

The low-fertility countries, particularly in Oceania, North America, and the West and North Europe, will have a minimum support ratio (see the following self-explained figures) (Fig. 8).

First demographic dividend. Source: Compiled by the author based on metadata from Mason et al. (2017)

Figure 9 shows that Africa has the highest potential to supply the labour force.

4.2 Economic life cycle: labour income and consumption in Africa

Figure 10 shows that at early and old age, people consume more but produce and earn less. To contrast the results, for regions, the consumption and labour income data are normalized using the min–max approach. When labour income is greater than aggregate consumption, there is a surplus to be saved and invested in, which leads to a demographic dividend. When consumption is greater than labour income, the gap is called a “life cycle deficit” (Mason et al. 2017). As shown in Fig. 10, compared to the other regions, children and youth cohorts in Africa start earning labour income at the earliest age, whereas American children start earning income late, i.e., after 16, but they consume more both in childhood and old age compared to other regions. Asians start earning an income at the age of 10 but consume less until old age.

First demographic dividend timing in Africa. Source: Sketched by the author based on data from IMF (2014)

4.3 Demographic dividend potential and timing in Africa

To achieve objective 2 in this section, the economic support ratio and the first demographic dividend are presented for Africa. As stated above, the economic support ratio could be calculated by the following equation (Bloom et al. 2003; Mason and Lee 2007; Lee and Mason 2010; Mason et al. 2017).

where r is economic support ratio, LY is life cycle labour income, and C is life cycle aggregate consumption.

The dividend is calculated by taking 1970 as a base year. Accordingly, Fig. 10 shows that, in comparative terms, Africa is at the top of the demographic dividend potential in the years 2022 onwards. On the other hand, Asia has been on top of the dividend potential since the 1960s. In fact, this is claimed to be the cause of the East Asian economic miracle (Bloom and Williamson 1998; Mason 2002; Bloom et al. 2003; Mason and Lee 2007; Mason et al. 2017).

Figure 3 shows that Africa has the robust potential for a first demographic dividend in the coming decades. However, the second demographic dividend does not show vigorous potential. This could be due to a variety of factors, including low per capita savings, a poor social security system, a lack of human capital, and other cultural and governance issues. As the simulation is based on old data, Africa can harness more than what is simulated as dividends beget dividends. However, if the potential is not used appropriately with the support of public policies, the demographic transition can even cause conflicts, called “demographic bombs” (Lin 2012).

Regarding the timing of the demographic dividend, African countries have different paces. As shown in Fig. 7, for example, Niger has not yet started to see its first dividend. On the other hand, Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, and Mauritius have already finished their first dividend span. In the meantime, in the last couple of decades, 47 have already started to see their first dividend potential. As a result, one may claim that the sustainable economic growth of Africa in the last two decades has been, inter alia, caused by demographic transition. Although the average two-decade economic growth is 4.5%, it is not substantial compared to the East Asian miracle. This leads to the claim that the potential is not well-harnessed, perhaps due to dearth of conducive policies and programs.

4.4 Age distribution of surplus labour

As portrayed in Fig. 11, about 78.4% of the current international migrants in the world are in the age range of 15–64. This shows that three-fourths of migrants can be sources of labour in the country of destination. Although migrants may have skill gaps in developed regions, the gaps could be resolved by training. However, determined public policies are required to have balanced growth between the global north and south. It does not mean that all migrants have economic reasons for migration, nor does it mean that all migrants could be classified as surplus or disguised labour from developing countries.

4.5 Drivers of demographic dividend

As explained above, the demographic dividend is often considered as growth in an economy caused by the demographic transition. Therefore, in the first step, as shown in the following table, the logarithm of real per capita income is used as a dependent variable, while the percentage of youth in the population, personal remittance, and policy score are used as independent variables. The OLS regression results are as per the hypotheses in that remittance and policy are related positively to per capita income, whereas the youth bulge has negatively influenced the income (see Table 3).

However, the economic dividend may not capture all the positive changes in economic, social, and political affairs due to the change in demographic structure. Therefore, the inclusive development index is used as a proxy for dependent variable (see Table 4).

4.6 Discussion of the dynamic panel data regression result

According to the regression result, the model is fitted as follows:

The regression results show that both the youth bulge and its lag variable are negatively correlated to the inclusive development index, but only slightly (see model 1 in Table 5). Even though the regression result confirms that the youth bulge has a negative effect on development, possibly due to ineffective labour-market policies, portraying the bulge as a ticking time bomb is deceptively embellished not only because the bulge is not statistically significant, but also, perhaps, for ethical reasons. Moreover, after controlling for the omitted youth data using the first difference method, the share of youth shows a positive correlation with inclusive development.

The size of the economy provides the momentum for further development. It is proxied by a per capita income, and it is statistically significant in all the models that have logical ground because, without a cake, talking about equity and intergenerational sustainability is gibberish. The proxy of policy and institutional quality (CPIA index) has a positive effect in the first model, but it is not statistically significant. Modern contraceptive methods’ prevalence rate and life expectancy have positive effects on inclusive development. Moreover, the rate of population growth and the unemployment rate have a negative effect on the dividend. On the other hand, structural change towards industrialization has a positive effect.

4.7 Robustness

The fixed effects regression is chosen in order to minimize the risk of endogeneity. Regarding the robustness test, first Pearson’s correlation matrix is drawn, and it shows no sign of multicollinearity. The youth bulge proxy and its lag variable, however, show a strong correlation. That is why, they are regressed in a separate model because if the variables are controlled in a single model, the result does not qualify the best linear unbiased estimator (BLUE) conditions. Moreover, the initial fixed effects regression models show heteroscedasticity when they are verified with the modified Wald test for groupwise heteroscedasticity. Therefore, as a corrective measure, the fixed effects models are regressed again to get a correlation coefficient with a robust standard error (presented in parenthesis). The fixed effects regression output in STATA 14 shows the correlation coefficient between the error terms and the explanatory variables. Accordingly, the coefficient indicates that there is no strong correlation. As a result, serial correlation (autocorrelation) is no longer a risk. Finally, the Hausman test of fixed versus random effects shows that fixed effects are consistent, whereas random effects are not. That is why, the overall inferences are drawn based on the fixed effects.

5 Deductions and public policy implications

The paper is different from the literature at least in four ways: (i) the available literature apparently neglects the role of relocating labour in optimizing the demographic dividend, but the current paper proposes a new conceptual framework, i.e., ISLC model which may provoke discourses in the area; (ii) based on secondary data from IMF (2014), the paper also presents when the window of opportunity for demographic dividend opens and closes in 47 African countries. Third, the paper conducts fixed effects regression to identify the drivers of demographic dividend. Accordingly, family planning facilities, maternal and child health, education, and women’s empowerment should be the targets for demographic and socioeconomic policies. Fourth, the paper uses two regression approaches. The first approach uses GDP as a proxy for demographic dividend and proves whether the ratio of youths in total population, institutional quality proxied by CPIA index, and circulation of labour proxied by remittance are significant drivers. As shown in Table 3, in the presence of inclusive institutions, circulation surplus labour from the region of abundance to the region of shortage has statistically significant positive effect on demographic dividend. Using ISLC model and bringing remittance into the democratic dividend discourse, the paper also uniquely presents the significance of labour circulation not only between rural and urban economic sectors but also internationally.

The second approach uses inclusive development index as a dependent variable, which is a novel approach in the paper. The logic is that, for example, if peace dividend (economic benefit of peace) and demographic bomb (such as political instability) should be considered, growth in terms of per capita income per se is not sufficient to measure the actual dividend. Thus, as the multidimensional inclusive development index considers multiple development variables, it may give a better picture. In this regard, the author has a detail account in a separate forthcoming research paper. Finally, based on the statistically significant variables, the paper statistically proves the hypotheses. Accordingly, on one hand, formal circulation of surplus labour may generate remittance and augment demographic dividend. On the other hand, inclusive governance institutions that promote family planning, address unemployment and health facilities, and augment human capital and empowerment of women are at the heart of harnessing demographic dividend. Moreover, most of youths under 24 years are not often active to enter into the labour market and may be due to schooling and college education. However, the regression shows that when the omitted variables are controlled through first difference, the effect of youth is positive on the dividend.

Data Availability

The data used in the research is accessible on request from the authors.

Notes

A demographic dividend is economic growth caused by a demographic shift towards a larger labour force compared to dependent age groups. Declining fertility and a mortality rate are the immediate causes of the transition. However, migration also plays a significant role.

Lin (2012) claims that if a large cohort of young people cannot find decent work and earn a satisfactory income, the youth bulge will become a demographic bomb, because a large mass of hopeless youth is likely to become a potential source of social and political instability. http://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/youth-bulge-a-demographic-dividend-or-a-demographic-bomb-in-developing-countries/ (accessed: 20 April 2021).

Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/theme/international-migration/index.asp. Accessed 20 October 2021.

The 2022 report is now available. However, the current paper depends on the 2019 report and it is available at: https://population.un.org/wpp/. (Accessed March 18, 2020). Using the UN data is found to be meritorious for its comprehensiveness and consistence for the fact that it has projections for long time.

It is available at: https://ntaccounts.org/web/nta/show. (Accessed January 18, 2020).

References

Acemoglu D, Johnson S, Robinson J (2005) Institutions as a fundamental cause of long-run growth. In: Acemoglu D, Johnson S, Robinson J (eds) Handbook of Economic Growth, vol 1, Part A, Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.35866/caujed.2021.46.2.003

Acemoglu D, Robinson JA (2016) Paths to inclusive political institutions. In: Eloranta J, Golson E, Markevich A, Wolf N (eds) 2016 Economic History of Warfare and State Formation. Studies in Economic History. Springer, Singapore

African Union (2017) AU Roadmap on harnessing demographic dividend through investment in youth: in response to AU assembly decision (Assembly/AU/Dec.601 (XXVI) on the 2017 theme of the year. Addis Ababa: African Union Commission

Bloom DE, Freeman RE (1986) The effects of rapid population growth on labour supply and employment in developing countries. Popul Dev Rev 12(3):381–414

Bloom DE, Williamson JG (1998) Demographic transitions and economic miracles in emerging Asia. World Bank Econ Rev 12:419–455

Bloom DE, Kuhn M, Prettner K (2017) Africa’s prospects for enjoying a demographic dividend. J Dem Econ 83(1):63–76

Bloom D, Canning D, Sevilla J (2003) The demographic dividend: a new perspective on the economic consequences of population change. RAND Corporation: Santa Monica. [Online]. https://doi.org/10.7249/MR1274

Bloom DE, Canning D, Fink G, Finlay J (2007) Realizing the demographic dividend: is Africa any different? PGDA Working Papers 2307, Program on the Global Demography of Aging

Boserup E (1965) The conditions of agricultural growth: the economics of agrarian change under population pressure. George Allen and Unwin Ltd, London

Boulding KE (1956) General systems theory: the skeleton of science. Manage Sci 2:197–208

Boulding KE (1984) The organizational revolution: a study in the ethics of economic organization. Greenwood Press, Westport

Boulding KE (1992) Towards a new economics: critical essays on ecology, distribution and other themes. Edward Elgar, Aldershot

Coale AJ, Hoover E (1958) Population growth and economic development in low-income countries. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Dramani L, Oga IJ (2017) Understanding demographic dividends in Africa: The NTA Approach. J Dem Econ 83(1):85–101. https://doi.org/10.1017/dem.2016.30

Ehrlich PR (1968) The Population Bomb. Ballantine Books, New York

Gendreau F (1991) The demography of development. Eur J Dev Res 3(2):59–69

Gil-Vasquez K, Elsner W (2022) Death cult. From neoliberalism to human waste to biopolitics, and from “individual freedom and competition” to “heroic death” Available (Online)

IMF (2014) Africa rising: Harnessing the demographic dividend. IMF Working Paper WP/14/143, International Monetary Fund

Kelley AC (2001) The population debate in historical perspective: revisionism revised. In: Birdsall N, Kelley A, Sinding S (eds) Population Matters: Demographic Change, Economic Growth, and Poverty in the Developing World. Published to Oxford Scholarship (Online): 24–54. Available at https://doi.org/10.1093/0199244073.001.0001. Accessed 20 Feb 2020

Kuznets S (1960) Population change and aggregate output in Universities–National Bureau Committee for Economic Research, Demographic and Economic Changes in Developed Countries. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Lammensalo LS (2021) Intersections of sexual and reproductive health and rights and climate change: a postcolonial feminist analysis. Master Thesis. Retrieved from: http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:hulib-202106303266. Accessed 10 Jan 2023

Lee R, Mason A (2010) Fertility, human capital, and economic growth over the demographic transition. Eur J Popul 26(2):159–182

Lee R, Mason A (2014) National transfer accounts and intergenerational transfers. [Online]. Available at: https://ntaccounts.org/web/nta/show/Applications. Accessed 14 Feb 2021

Lewis WA (1954) Economic development with unlimited supplies of labour. Manchester School 28:139–191

Lin JY (2012) Youth bulge: a demographic dividend or a demographic bomb in developing countries? [Blog] Available at: https://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/youth-bulge-a-demographic-dividend-or-a-demographic-bomb-in-developing-countries. Accessed 20 Apr 2021

Mason A (2002) Population change and economic development. challenges met, opportunities seized. Stanford University Press, Stanford

Mason A, Kinugasa T (2008) East Asian economic development: two demographic dividends. J Asian Econ 19(5–6):389–399

Mason A, Lee R (2007) Transfers, capital, and consumption over the demographic transition. In: Robert C, Ogawa N, Mason A (eds) (2007) Population Aging, Intergenerational Transfers and the Macroeconomy. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 128–162

Mason A, Lee R, Jiang JX (2015) Demographic dividends, human capital, and saving. J Econ Ageing Apr (7):106–122

Mason A, Lee R, Abrigo M, Lee SH (2017) Support ratios and demographic dividends: estimates for the world. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division Technical Paper No. 2017/1. New York: United nations

May JF, Guengant JP (2020) Demography and economic emergence of sub-Saharan Africa (Series Pocket Book Academy, Vol. 134-EN). Académie royale de Belgique

Molero-Simarro R (2016) Is China reaching the lewis turning point? Agricultural Prices, Rural Urban Migration and the Labour Share. J Aust Polit Econ 78:48–86

Moreland S, Madsen EL, Kuang B, Hamilton M, Jurczynska K, Brodish P (2014) Modeling the demographic dividend: technical guide to the DemDiv model. Washington, DC: Futures Group, Health Policy Project. [Online]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.4162.1607. Accessed 19 Dec 2020

North D, Wallis J, Weingast B (2009) Violence and the rise of open-access orders. J Democr 20(1):55–68

Obeng-Odoom F (2021) Global migration beyond limits. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Obeng-Odoom F (2022) Spatial political economy: the case of metropolitan industrial policy. Rev Evol Polit Econ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43253-022-00078-3

Prskawetz Aa, Sambt J (2014) Economic support ratios and the demographic dividend in Europe. Demogr Res 30(34):963–1010

Rodrik D, Subramanian A, Trebbi F (2004) Institutions rule: The primacy of institutions over geography and integration in economic development. J Econ Growth 9:131–165. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOEG.0000031425.72248.85

Seltzer JR (2002) The origins and evolution of family planning programs in developing countries. RAND Corporation, Santa Monica

Ssebbaale EM, Kibukamusoke M (2016) Demographic dividend in Africa, prospects, opportunities and challenges: a case study of Uganda. Researchjournali’s Journal of Sociology 4(6):1–11

Stanley A (2018) Getting the youth bulge wrong. [Online]. Retrieved from: https://politicalviolenceataglance.org/2018/02/15/getting-the-youth-bulge-wrong/. Accessed 17 May 2021

United Nations (1973) The determinants and consequences of population trends. Population Studies No. 50, 2 vols. New York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs

United Nations (2017/8) Population facts. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. [Online]. Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/popfacts/PopFacts_2017-8.pdf. Accessed on 25 Dec 2021

United Nations (2019) World population prospects 2019: highlights. ST/ESA/SER.A/423. DESA, Dessa Population Division. [Online]. Retrieved from: https://population.un.org/wpp. Accessed 17 May 2021

WEF (2017) The inclusive growth and development report. World Economic Forum, Geneva

Woldegiorgis MM (2020b) The social market economy model in Africa: a policy lesson in the pursuit of an inclusive development. PanAfrican Journal of Governance and Development 1(2):100–125

Woldegiorgis MM (2020a) Modeling institutional reengineering for inclusive development (IRID) in Africa. PanAfrican Journal of Governance and Development 1(1):102–132. http://ejhs.ju.edu.et/index.php/panjogov/article/view/1369

Woldegiorgis MM (2022a) Inequality, social protection policy, and inclusion: pertinent theories and empirical evidence. J Soc Econ Dev. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40847-022-00185-1

Woldegiorgis MM (2022b) Social structure, economic exclusion, and fragility? Pertinent theories and empirics from Africa. In: AlDajani IM, Leiner M (eds) Reconciliation, Heritage and Social Inclusion in the Middle East and North Africa. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-08713-4_23

Acknowledgements

The author sincerely acknowledges the financial support of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation (KAS).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

As the manuscript includes empirical findings, the author consents to providing the meta when it is required. The author also permits duplication and reproduction of the manuscript based on the ethical standards of the Review of Evolutionary Political Economy.

Conflict of interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Woldegiorgis, M.M. Drivers of demographic dividend in sub-Saharan Africa. Rev Evol Polit Econ 4, 387–413 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43253-023-00094-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43253-023-00094-x