Abstract

Camouflaging refers to behaviours observed in autistic people to hide or compensate for difficulties experienced during social interaction. As it is unknown to what extent neurotypical individuals camouflage, this study looked at camouflaging and mental well-being in the general population. We employed a cross-sectional survey design to recruit 164 people (123 female, 35 male, 5 non-binary, 1 prefer not to say) between 18 and 65 years of age online. Participants filled in measures of autistic traits, camouflaging, social anxiety, generalised anxiety and presence of autism diagnosis (5 self-diagnosed, 5 diagnosed, 154 not diagnosed) and additional mental health diagnoses. Camouflaging was significantly correlated with autistic traits, social anxiety, generalised anxiety and age. Hierarchical regression analyses revealed that autistic traits and social and generalised anxiety predicted camouflaging. Logistic regression analyses for mental health diagnoses showed camouflaging significantly reduced risk of depression, although the effect was small. No other mental health diagnoses were predicted by camouflaging. Neurotypical individuals who have higher autistic traits and experience more social and/or generalised anxiety may be more likely to camouflage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Autism spectrum conditions (ASCs) are characterized by difficulties in social interaction and communication, restricted and repetitive behaviours and interests and activities (APA, 2013). Autism occurs in around 1% of the population, with men being about four times more likely to be diagnosed than women (Corbett et al., 2021). Although men are more likely to be diagnosed, recent population-based studies suggest lower true sex/gender ratios of about 3:1 (men-women) (Loomes et al., 2017) or even 2:1 (Corbett et al., 2021), and camouflaging is one factor proposed to influence differences in diagnostic rates (Lai et al., 2011). Camouflaging refers to a strategy to hide or compensate for an individual’s autistic traits (Hull et al., 2019a) and has been reported as a conscious or unconscious behaviour to appear less autistic during social interactions. Behaviours can include use of learned phrases, making eye contact, mimicking social behaviour, learning social scripts and imitation of facial expressions (Lai & Baron-Cohen, 2015).

Camouflaging arises as a discrepancy between the external and internal states of autistic individuals (Lai et al., 2017). Hence, autistic individuals may feel uncomfortable because of other people’s responses during social interaction and camouflage to address this. From an outside perspective, individuals suppress internal stress truly experienced to adjust to society, to meet social norms and reduce likelihood of stigmatisation (Schneid & Raz, 2020). Hull et al. (2017) qualitatively explored motivations of camouflaging in adults with ASC and identified main themes of the desire “to fit in”. Camouflaging was used to obtain jobs, be a member of society and “blend in with the normal” (Hull et al., 2017, p.5). Even though camouflaging can help to compensate for social difficulties experienced, the constant need to camouflage may negatively impact mental health. Camouflaging is reported to be mentally and physically draining; individuals report increased levels of anxiety and stress, with a minority of people reporting some relief or satisfaction after camouflaging (Hull et al., 2017). Camouflaging in autistic individuals is associated with poor mental health outcomes and may lead to symptoms of anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, even loss of identity and suicidal ideation (Cage & Troxell-Whitman, 2019; Tubio-Fungueirino et al., 2020). There is evidence that neurotypical individuals also camouflage to hide autism-like characteristics (Beck et al., 2020). However, the effects of camouflaging on neurotypical individuals’ mental health are unknown.

Qualitative research on camouflaging in autistic individuals suggests that individuals who camouflage are more likely to experience anxiety (Cage & Troxell-Whitman, 2019). An association between greater symptoms of social anxiety (SAD) and generalised anxiety (GAD) and camouflaging was previously observed in autistic adults (Hull et al., 2021); however, we do not know whether such relationship exists in the general population. Neurotypical individuals may mask autistic traits in social situations, but camouflaging research in the neurotypical population is scarce, and motivations or consequences in the general population remain unknown. Anxiety is common in the general population, with a prevalence of around 7.3% (Baxter et al., 2013). Neurotypical individuals may fear negative evaluation of others during social interaction or feelings of being overwhelmed by everyday activities (Munir & Takov, 2021).

There is a lack of distinction between SAD and GAD in many previous studies in autistic populations, making it hard to untangle the relationship between anxiety and camouflaging (Hull et al., 2021). Hull et al. (2021) investigated mental health problems in autistic adults. Self-report measures of GAD, depression and SAD were associated with higher levels of camouflaging. According to these findings, camouflaging may be a risk factor for development of anxiety and/or other mental health problems. It is important to distinguish forms of anxiety to identify situations in which autistic—or neurotypical—individuals are more likely to camouflage. The direction of the relationship between anxiety and camouflaging has not yet been determined; it may be that in some cases (for autistic or non-autistic people), the presence of an anxiety disorder increases likelihood of camouflaging (Cage & Troxell-Whitman, 2019).

As SAD is more closely related to social interaction, individuals with SAD may be more likely to camouflage in comparison to individuals with GAD. Thus, it is important to explore whether an individual’s underlying level of anxiety can predict how much someone camouflages.

Additionally, the previously observed association between camouflaging and other mental health conditions, such as depression and suicidality, raises the question of whether camouflaging itself is associated with specific mental health conditions. Individuals with high autistic traits who camouflaged more in the study by Beck et al. (2020) were more likely to experience negative consequences, including depression and suicidal thoughts. Therefore, it is important to explore the relationship between camouflaging and specific mental health conditions among the general population.

As the current literature shows, more research is needed to explore the role of camouflaging and its association with GAD and SAD. In this study, we will explore whether camouflaging is related to generalized and social anxiety in the general population. In addition, we know that camouflaging is associated with poorer mental health outcomes in autistic people, showing increased numbers of co-occurring mental health conditions. Therefore, the presence of mental health condition(s) and its association with camouflaging will be investigated in the general population. As camouflaging has been previously associated with both autistic traits (Hull et al., 2019b) and gender (Hull et al., 2019a), both these characteristics will be controlled for in all analyses. Subsequently, the following questions will be addressed.

Research Questions

-

(1)

Do people who camouflage more, show higher social anxiety and generalised anxiety scores?

-

(2)

Is there an association between camouflaging and presence of a mental health diagnosis?

Methods

We employed an online, quantitative cross-sectional design, to explore the role of camouflaging, SAD and GAD in the general population. The independent variable was camouflaging, to investigate its association with the outcome variables (1) SAD, (2) GAD and (3) mental health diagnosis.

Participants

In total, we recruited 230 participants between the age of 18 and 65 (M = 26.68, SD = 11.13) from the general population via convenience sampling. Participants were recruited through the researchers’ networks, social media and snowball sampling, from May to July 2021. Inclusion criteria were to be aged between 18 and 65 years and have sufficient English language comprehension to complete an online survey; there were no other exclusion criteria. One participant did not report their age. Individuals were asked to specify their gender (male = 35, female = 123, non-binary = 5, 1 = prefer not to say) and whether they have an autism diagnosis (autism = 5, not diagnosed = 154, self-diagnosed autism = 5). It was assumed that participants had sufficient English skills to participate. No information was available about participants’ location or other demographic factors, including race/ethnicity, though the study itself was conducted in the UK.

Materials

Broader Autism Phenotype Questionnaire (BAP-Q)

The BAP-Q (Hurley et al., 2007) consists of 36 items on a 6-point Likert-scale (1 = very rarely, 6 = very often) with questions referring to personality and language characteristics, based on autistic individuals’ relatives. It contains three sub-scales (aloof personality, pragmatic language problems, rigid personality) with 12 items per sub-scale, higher scores indicating increasing likelihood of present autism phenotype. The questionnaire has high sensitivity and specificity (> 70%), has high internal consistency across all items (α = 0.95) and was found to be valid for identifying phenotypes in males as well as females (Hurley et al., 2007).

Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire (CAT-Q)

The CAT-Q is a self-report questionnaire looking at levels of camouflaging (Hull et al., 2017). It contains 25 items on a 7-point Likert-scale and has three sub-scales (compensation, masking, assimilation). Scores range from 25 to 175, with higher scores indicating higher levels of camouflaging. The scale has been validated in autistic and non-autistic samples and shows good internal consistency (α = 0.89) (Hull et al., 2019b).

Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS) and Social Phobia Scale (SPS)

The SIAS and SPS (Mattick & Clarke, 1998) were developed as companion measurements. The SIAS assesses general aspects of social interactions, while the SPS looks at fears experienced during routine activities (e.g. eating). Both scales consist of 20 items scored on 5-point Likert scales and show good internal consistency (α = 0.89 for SPS, α = 0.90 for SIAS) and validity. Higher scores indicate more symptoms of SAD. The measurements are recommended to be used together and were found to be adequate in an autistic population (Boulton & Guastella, 2021).

Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7)

The GAD-7 is a 7-item self-report questionnaire to examine GAD symptom (Spitzer et al., 2006). Symptoms of anxiety over the past 2 weeks are rated on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = not at all, 3 = nearly every day). Scores range from zero to 21, higher scores showing more anxiety. The questionnaire has excellent interact consistency (α = 0.92) (Löwe et al., 2008).

Procedure

Ethical approval was granted by the University College London ethics committee (reference 19896.001). The study was performed in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. We recruited participants via social media (Twitter, Facebook and Instagram), using an advert which contained a link to the study on Qualtrics, and university students from University College London (UCL) through internal student research systems. Participants gave informed consent for anonymised data to be included in the study. Participants then answered demographic questions, before filling in the BAP-Q, CAT-Q, SIAS, SPS and GAD-7, which took around 26 min. Finally, participants reported mental health diagnoses via free-text entries. Once finished, they received a debrief sheet with support resources in case of psychological discomfort. UCL students received credits and every participant could enter the prize draw for a £100 Amazon voucher.

Analyses

We used STATA (StataCorp., 2019) to explore associations between camouflaging and autistic traits, SAD, GAD and age. Total scores were explored to examine the relationship between the concept of camouflaging and outcome variables. Multiple correlation analyses examined the direction and strength of the relationship between camouflaging and each variable. Although two questionnaires (SPS and SIAS) were used to measure SAD as one concept, both questionnaires were evaluated individually for correlational analyses.

Question 1

Hierarchical regression models examined how camouflaging is predicted by autistic traits, SAD and GAD. We controlled for age and gender (Model 1) and autistic traits (Model 2). SPS and SIAS were entered into the model at the same time to explore the concept of SAD itself (Model 3), and then GAD was added (Model 4).

Question 2

New variables were generated from the free-text entries for having a “Mental Health Diagnosis” in general, “Anxiety”, “Depression” and “Eating Disorders”, and a separate variable that accounted for all “Other Diagnoses” (obsessive compulsive disorder, bipolar disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder and emotionally unstable personality disorder; see Table 1). This allowed us to run logistic regression models (controlling for autism and age), to see whether presence of camouflaging increased likelihood of a mental health diagnosis.

Results

A total of 230 participants were recruited initially. After removing participants with missing data, a full sample with completed measures was obtained from 164 participants (Table 1). Based on an a priori power calculation, 146 participants were needed to achieve a small to medium effect with 90% power, α = 0.05.

Multiple correlation analyses (Table 2) examined whether there was an association between individuals’ level of camouflaging and autistic traits. Results showed a highly significant positive moderate correlation; higher camouflaging scores indicated higher autism traits. Highly significant strong positive correlations were found between camouflaging and both SAD measures. If SAD increased, camouflaging behaviours also increased. A significant weak positive correlation between camouflaging and GAD was observed. Camouflaging was weakly associated with greater GAD. Lastly, a significant weak negative correlation between camouflaging and age was reported, meaning that levels of camouflaging decreased with increasing age.

A hierarchical linear regression analysis evaluated the role of SAD and GAD on camouflaging when controlling for BAP scores. Age and gender were first added to the model to control for them. For the first analysis, BAP was included as a predictor, which was highly significant (F(3, 159) = 13.13, p < 0.001). Additionally, the adjusted R2 value of 0.18 associated with this model suggests that autistic traits account for up to 11.7% of the variation in camouflaging scores, though age and gender variables were not significant. For every one-unit increase in camouflaging, BAP scores increased by 0.54. The final model (Table 3) included all predictors and explained around 54.67% of variance in camouflaging. The full model is available in the Online Resources (Table S1).

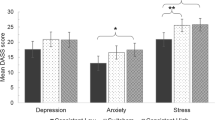

Finally, we wanted to see whether there was a relationship between camouflaging and presence of a mental health diagnosis. Camouflaging did not contribute to having a mental health diagnosis overall, anxiety, eating disorders nor other diagnoses (Table 4). However, camouflaging was found to predict diagnosis of depression. The estimated odds ratio showed a decrease of around 2.6% (OR = 0.97, 95% CI 951–0.997) in depression scores for every one-unit increase in camouflaging. Thus, camouflaging more may reduce the likelihood of having a diagnosis of depression.

Discussion

The aims of the study were to explore camouflaging behaviours and associated generalised and social anxiety in the general population and to explore the extent to which other mental health diagnoses may be predicted by camouflaging behaviours in the general population.

Initially, we observed significant positive correlations between autistic traits, social anxiety (SAD), generalised anxiety (GAD) and camouflaging. SAD and GAD were also found to significantly predict greater camouflaging in the regression analyses. The findings are consistent with Hull et al. (2021), who found associations between camouflaging and SAD and GAD in autistic individuals. The present study was the first to assess the relationship between anxiety and camouflaging in the general population. The regression models showed that SAD accounted for more variance than GAD, suggesting that SAD has greater influence than GAD on camouflaging among neurotypicals. A stronger relationship between SAD and camouflaging in comparison to GAD and camouflaging may be explained by the fact that camouflaging is defined as a strategy used to overcome social difficulties (Hull et al., 2017). GAD scores were only weakly correlated with camouflaging. Intense worries associated with GAD may not necessarily increase camouflaging in social contexts and may play less of a role during social interaction.

Sub-clinical autistic traits were similar across males (M = 3.36; SD = 0.35) and females (M = 3.41; SD = 0.35) in our sample, although this difference was not tested statistically. Non-binary individuals scored higher than males or females on all measures obtained, although again these differences were not tested statistically. Consistent with this, Hull et al. (2019a) reported higher camouflaging scores in non-binary individuals regardless of autism diagnosis. However, the sample size of our non-binary sample was underpowered, which means that we are unable to make any inferences from these findings. Although no significant correlations between camouflaging and measures of mental health were found in the non-binary sub-sample in Hull et al. (2019a), emerging evidence from non-binary samples suggests this group may be more likely to engage in camouflaging than binary gendered people (Sedgewick et al., 2020).

Self-report measures on mental health diagnoses were used to investigate whether camouflaging is related to mental health conditions beyond anxiety. We found that camouflaging significantly predicted the likelihood of being diagnosed with depression, but no other mental health diagnoses (anxiety, eating disorders, or other diagnoses), and did not predict overall likelihood of having a mental health diagnosis. This is in contrast to previous research in autistic populations, which found that those who camouflage more have higher likelihood of meeting diagnostic criteria for anxiety and depression (Hull et al., 2021). That said, small numbers of participants reporting specific mental health diagnoses mean our analyses may have been underpowered. Subsequently, exploring camouflaging levels and mental health in a clinical neurotypical sample (i.e. recruiting specifically from groups with mental health conditions, rather than the general population) may identify differences in well-being (Livingston et al., 2019).

Greater use of cognitive resources and internal monitoring may increase autistic individuals’ risk of additional mental health problems (Lai et al., 2017). However, neurotypical individuals might be able to engage in the same levels of camouflaging with less effort, which could reduce the likelihood of mental health issues at the clinical level (Lai et al., 2015). However, researchers have yet to establish a causal relationship between camouflaging and mental health difficulties, and the relationship may be bidirectional (Chapman et al., 2022). Some individuals may develop mental health problems as a result of camouflaging, while others may already have mental health problems, for which they camouflage to fit into society. This could mean that both autistic and neurotypical people camouflage and experience associated negative consequences, but the reason for camouflaging may differ between groups. Qualitative research may facilitate exploration of these potentially causal relationships.

Surprisingly, camouflaging predicted decreased likelihood of a diagnosis of depression. Individuals were 2.6% less likely to be diagnosed as depressed when camouflaging more, meaning that camouflaging could be a protective factor for depression in non-autistic people. It is important to note that this is a small effect size, and therefore, the impact at a clinical level might be diminished. In addition, we cannot establish a causal or directional relationship. One explanation for this finding is that individuals who have been diagnosed with depression may already receive more support than individuals who are not diagnosed. Therefore, access to or existing support might lead to reduced levels of camouflaging in the general population. Alternatively, individuals who camouflage their autistic traits more, may also camouflage symptoms of depression, and so may be less likely to receive a diagnosis of depression.

In contrast, autistic individuals report camouflaging to be exhausting and mentally draining, which can negatively influence symptoms of depression (Bernardin et al., 2021). This raises the question, whether neurotypical individuals are more likely to use camouflaging behaviours to maintain self-monitoring. Autistic individuals may memorise scripts to aid conversation flow in everyday life, whereas neurotypical individuals may rehearse sentences to prevent public embarrassment (Gray et al., 2019). Although use of those behaviours to overcome anxiety may be referred to as camouflaging, behaviours used for impression management may not represent the idiosyncratic camouflaging originally observed in autistic individuals (Schneid & Raz, 2020).

Successful impression management by non-autistic people may help to prevent depression by increasing social competency, while autistic individuals who engage in strong camouflaging behaviours say that they feel like they lose themselves in the process (Hull et al., 2017). Non-autistic adults report lower levels of thwarted belonging than autistic adults, which is associated with camouflaging (Cassidy et al., 2020; Pelton et al., 2020). This potential impact of camouflaging on belonging may contribute to poor sense of identity, and even suicidality (Cassidy et al., 2020). In reference to our findings, camouflaging may be less likely to negatively impact the sense of identity or belonging in non-autistic individuals. Neurotypical individuals may have a stronger sense of identity, which could potentially decrease likelihood of a diagnosis of depression because of their camouflaging.

In the present study, neurotypical individuals engaged in relatively low levels of camouflaging (M = 91.09), whereas individuals with a formal diagnosis of autism (M = 115.6) and self-diagnosed individuals (M = 114.6) scored comparably high to autistic individuals as reported in other research (Hull et al., 2019b). However, the number of autistic participants was too small to allow for statistical comparison between groups. Our results might be indicative of potentially positive consequences of camouflaging for some individuals. When exploring compensatory behaviours in clinical mental health settings, it may be helpful to know that camouflaging is not necessarily a purely negative behaviour for all autistic people (Hull et al., 2017).

Strengths and Limitations

The study provides novel insights into the relationship between GAD, SAD and camouflaging in the general population. Furthermore, distinction between GAD and SAD allows for a more refined analysis between camouflaging behaviours and anxiety experienced.

The study contained some limitations. Firstly, recruitment of participants was conducted online; therefore, individuals without access to social media or sufficient English skills were unable to participate. Individuals with intellectual disabilities (IDs) were not included in this study, meaning that findings are not generalisable across a broader range of experiences. Individuals with ID remain greatly understudied and excluded from research (Lai et al., 2006). It is yet unknown whether individuals with ID also engage in camouflaging behaviours, with very limited camouflaging research that includes autistic people with ID (Cook et al., 2021).

Limited sample size of sub-groups with specific mental health diagnoses reduced the ability to further explore the relationships between these and camouflaging. In addition, individuals freely entered their own mental health diagnoses, meaning that there was variation in the specificity of diagnoses reported. For instance, some individuals specified a diagnosis of GAD, whereas others stated just “anxiety”. In administering SAD and GAD measures, we did attempt to capture both forms of anxiety, but more specified self-reported diagnoses would have aided dissemination of different types of mental health conditions observed in camouflaging. Gendered comparisons were also limited by the small number of non-binary participants in this sample. As non-binary autistic individuals are more likely to experience mental health issues compared to cisgender autistic people, inclusion of larger minority group samples may help to identify reasons for camouflaging and mental health difficulties (Sedgewick et al., 2020).

Future Research

There is no current research comparing autistic and non-autistic individuals’ motivations for camouflaging. Subsequently, it is questionable whether neurotypical individuals truly camouflage due to social difficulties, or whether camouflaging reported by non-autistic people is in fact the same as impression management. Thus, it is important to qualitatively explore neurotypical individuals’ motivations for camouflaging. Furthermore, raising awareness of camouflaging among neurotypical individuals may lead to an improved understanding of neurodiverse groups (Wood-Downie et al., 2020).

There are few studies of camouflaging to date that included self-diagnosed autistic individuals (Bradley et al., 2021). Considering the fact that self-diagnosed individuals may also be more likely to be missed by clinicians, this group may show higher levels of camouflaging. In consequence, high levels of camouflaging reported by this group may also increase risk of mental health problems (Wood-Downie et al., 2020). As reported by Hull et al. (2019b), late diagnosis and camouflaging can increase mental health difficulties, and camouflaging is associated with suicidality in autistic males and females (Cassidy et al., 2018). Thus, autism diagnosis itself may be less indicative of how much someone camouflages compared to the presence of autistic characteristics that impact someone’s daily life. Investigation of characteristics observed in individuals with autism, as well as neurotypical individuals, may help to explain high levels of heterogeneity observed in the autistic population (Muggleton et al., 2019). Additionally, findings may also help professionals to develop interventions to address camouflaging efforts in autistic individuals. Individual differences in autistic people should be taken into consideration, to ensure the intervention is in line with the person’s values and well-being (Crane et al., 2018).

Implications

Our findings suggest a stronger relationship between camouflaging and social anxiety than generalised anxiety in the general population. Clinicians working with socially anxious individuals should therefore be particularly aware that they may be camouflaging autistic traits and should offer support including, if appropriate, referring for an autism assessment. Although we found camouflaging was associated with reduced likelihood of being diagnosed with depression, we would caution clinicians against assuming that camouflaging is beneficial or protective against depression. More research is needed to understand the complex relationship, including inclusion of other clinical mental health samples (i.e. people with diagnoses of anxiety or depression). While our findings suggest that camouflaging may be associated with reduced depression in neurotypicals, other groups may show different outcomes. We also suggest that screening for camouflaging in individuals with social anxiety may allow for better, more personalised, support. In consequence, assessing camouflaging and mental well-being—benefits and/or negative consequences—can inform clinical practice to develop appropriate care at an individual level. Furthermore, it is difficult to establish a causal relationship between camouflaging and mental health measures, which could be addressed in future longitudinal research. Qualitative research into autistic and non-autistic people’s experiences of camouflaging and mental health could inform clinical practice so clinicians can best support their patients who may be camouflaging. Autism is highly heterogeneous, reflecting a variety of presentations and outcomes (Beck, 2019). While there are current attempts to use deep phenotyping measures to disseminate the role of different strengths, weaknesses, and biological and behavioural characteristics observed in autistic individuals (Isaksson et al., 2018), capturing camouflaging behaviours through a range of different approaches could aid identification of different behaviours.

Since autistic people consistently report high levels of depression and anxiety associated with camouflaging, it is beneficial to note that the impact of camouflaging on neurotypicals may be more complex and may not always be harmful. Awareness of camouflaging increases awareness that individuals may be missed in clinical practice. As those individuals may be more likely to experience mental health difficulties (Beck et al., 2020), recognising camouflaging when assessing individuals may promote well-being. In some cases, receiving an autism diagnosis can encourage acceptance of “being different” and reduces the need to camouflage (Bradley et al., 2021).

Conclusions

This study found that autistic traits, social anxiety and generalised anxiety disorder are all associated with greater camouflaging in the general population. The findings replicated associations between camouflaging and poor mental health observed in the autistic population and demonstrated for the first time that there may be a stronger link between social anxiety and camouflaging than between general anxiety and camouflaging. Clinicians working with individuals with social anxiety should be aware that their patients may camouflage some aspects of their experiences. Camouflaging may also have some positive impact on mental health for individuals in the general population, although further research is required.

Data availability

Data used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

Baxter, A. J., Scott, K. M., Vos, T., & Whiteford, H. A. (2013). Global prevalence of anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-regression. Psychological Medicine., 43, 897–910. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171200147X

Beck, J. S., Lundwall, R. A., Gabrielsen, T., Cox, J. C., & South, M. (2020). Looking good but feeling bad: “Camouflaging” behaviours and mental health in women with autistic traits. Autism, 24, 809–821. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320912147

Beck, J. (2019). Camouflaging in women with autistic traits: Measures, mechanisms, and mental health implications. Theses and Dissertations. 8589. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/8589

Bernardin, C. J., Lewis, T., Bell, D., & Kanne, S. (2021). Associations between social camouflaging and internalising symptoms in autistic and non-autistic adolescents. Autism, 25(6), 1580–1591. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361321997284

Boulton, K. A., & Guastella, A. J. (2021). Social anxiety symptoms in autism spectrum disorder and social anxiety disorder: Considering the reliability of self-report instruments in adult cohorts. Autism Research, 14(11), 2383–2392. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2572

Bradley, L., Shaw, R., Baron-Cohen, S., & Cassidy, S. (2021). Autistic adults’ experiences of camouflaging and its perceived impact on mental health. Autism in Adulthood, 3(4), 320–329. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2020.0071

Cage, E., & Troxell-Whitman, Z. (2019). Understanding the reasons, contexts and costs of camouflaging for autistic adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49, 1899–1911. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-03878-x

Cassidy, S., Bradley, L., Shaw, R., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2018). Risk markers for suicidality in autistic adults. Melcular Autism, 9, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-018-0226-4

Cassidy, S. A., Gould, K., Townsend, E., Pelton, M., Robertson, A. E., & Rodgers, J. (2020). Is camouflaging autistic traits associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviours? Expanding the interpersonal psychological theory of suicide in an undergraduate student sample. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(10), 3638–3648. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04323-3

Chapman, L., Rose, K., Hull, L., & Mandy, W. (2022). “I want to fit in… but I don’t want to change myself fundamentally”: A qualitative exploration of the relationship between masking and mental health for autistic teenagers. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 99, 102069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2022.102069

Cook, J., Hull, L., Crane, L., & Mandy, W. (2021). Camouflaging in autism: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 89, 102080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102080

Corbett, B. A., Schwartzman, J. M., Libsack, E. J., Muscatello, R. A., Lerner, M. D., Simmons, G. L., & White, S. W. (2021). Camouflaging in autism: Examining sex-based and compensatory models in social cognition and communication. Autism Research., 14, 127–142. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2440

Crane, L., Batty, R., Adeyinka, H., Goddard, L., Henry, L. A., & Hill, E. L. (2018). Autism diagnosis in the united kingdom: Perspectives of autistic adults, parents and professionals. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders., 48, 3761–3772. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3639-1

Gray, E., Beierl, E. T., & Clark, D. M. (2019). Sub-types of safety behaviours and their effects on social anxiety disorder. PLoS ONE, 14, e0223165. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223165

Hull, L., Petrides, K. V., Allison, C., Smith, P., Baron-Cohen, S., Lai, M.-C., & Mandy, W. (2017). “Putting on my best normal”: Social camouflaging in adults with autism spectrum conditions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3166-5

Hull, L., Lai, M.-C., Baron-Cohen, S., Allison, C., Smith, P., Petrides, K. V., & Mandy, W. (2019). Gender differences in self-reported camouflaging in autistic and non-autistic adults. Autism, 24(2), 352–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361319864804

Hull, L., Mandy, W., Lai, M.-C., Baron-Cohen, S., Allison, C., Smith, P., & Petrides, K. V. (2019). Development and validation of the camouflaging autistic traits questionnaire (cat-q). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49, 819–833. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3792-6

Hull, L., Levy, L., Lai, M.-C., Petrides, K. V., Baron-Cohen, S., Allison, C., Smith, P., & Mandy, W. (2021). Is social camouflaging associated with anxiety and depression in autistic adults? Molecular Autism, 12, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-021-00421-1

Hurley, R. S. E., Losh, M., Parlier, M., Reznick, J. S., & Piven, J. (2007). The broad autism phenotype questionnaire. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders., 37, 1679–1690. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0299-3

Isaksson, J., Tammimies, K., Neufeld, J., Cauvet, E., Lundin, K., Buitelaar, J. K., . . . & EU-AIMS LEAP group. (2018). EU-AIMS longitudinal European autism project (leap): The autism twin cohort. Molecular Autism, 9(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-018-0212-x

Lai, M.-C., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2015). Identifying the lost generation of adults with autism spectrum conditions. Lancet Psychiatry, 2, 1013–1027. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00277-1

Lai, M.-C., Elliott, D., & Quellette-Kuntz, H. (2006). Attitudes of research ethics committee members towards individuals with intellectual disabilities: The need for more research. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 3, 114–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-1130-2006-00062.x

Lai, M.-C., Lombardo, M. V., Auyeung, B., Chakrabarti, B., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2015). Sex/gender differences and autism: Setting the scene for future research. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54, 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.003

Lai, M.-C., Lombardo, M. V., Pasco, G., Ruigrok, A. N. V., Wheelwright, S. J., Sadek, S. A., . . . & Baron-Cohen, S. (2011). A behavioural comparison of male and female adults with high functioning autism spectrum conditions. PLoS ONE. 6, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0020835

Lai, M.-C., Lombardo, M. V., Ruigrok, A. N., Chakrabarti, B., Auyeung, B., Szatmari, P., . . . & Baron-Cohen, S. (2017). Quantifying and exploring camouflaging in men and women with autism. Autism. 21, 690–702. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361319878559

Livingston, L. A., Shah, P., & Happe, F. (2019). Compensatory strategies below the behavioural surface in autism: A qualitative review. Lancet Psychiatry, 6, 766–777. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30224-X

Loomes, R., Hull, L., & Mandy, W. (2017). What is the male-to-female ratio in autism spectrum disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry., 56, 466–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.013

Löwe, B., Decker, O., Müller, S., Brähler, E., Schellberg, D., Herzog, W., & Yorck Herzberg, P. (2008). Validation and standardisation of the generalised anxiety disorder screener (HAD-7) in the general population. Medical Care, 46, 266–274. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093

Mattick, R. P., & Clarke, J. C. (1998). Development and validation of measures of social phobia scrutiny fear and social interaction anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36, 455–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(97)10031-6

Muggleton, J. T. B., MacMahon, K., & Johnston, K. (2019). Exactly the same but completely different: A thematic analysis of clinical psychologists’ conceptions of autism across genders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders., 62, 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2019.03.004

Munir, S., & Takov, V. (2020). Generalized anxiety disorder (gad) [updated 2019 Nov 22]. Statpearls [internet]. Treasure island (fl): Statpearls publishing.

Pelton, M. K., Crawford, H., Robertson, A. E., Rodgers, J., Baron-Cohen, S., & Cassidy, S. (2020). Understanding suicide risk in autistic adults: Comparing the interpersonal theory of suicide in autistic and non-autistic samples. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders., 50, 3620–3637. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04393-8

Schneid, I., & Raz, A. E. (2020). The mask of autism: Social camouflaging and impression management as coping/normalization from the perspectives of autistic adults. Social Science & Medicine., 248, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112826

Sedgewick, F., Leppanen, J., & Tchanturia, K. (2020). Gender differences in mental health prevalence in autism. Advances in Autism. https://doi.org/10.1108/AIA-01-2020-0007

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalised anxiety disorder. Archives of Internal Medicine., 166, 1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

StataCorp. (2019). Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC.

Tubio-Fungueirino, M., Cruz, S., Sampaio, A., Carracedo, A., & Fernandez-Prieto, M. (2020). Social camouflaging in females with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04695-x

Wood-Downie, H., Wong, B., Kovshoff, H., Mandy, W., Hull, L., & Hadwin, J. A. (2020). Sex/gender differences in camouflaging in children and adolescents with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04615-z

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support of Professor Will Mandy in planning this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SL and LH conceived and designed the study. SL collected the data, analysed the results, and wrote the first draft. SL and LH revised the manuscript and approved submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Declarations

Participant payments were provided by the Division of Psychiatry at University College London, as part of Shania Lorenz’s MSc in Clinical Mental Health Sciences. No other funding sources were used during this study. Laura Hull is currently supported by the Elizabeth Blackwell Institute, University of Bristol, the Wellcome Trust and the Rosetrees Trust, but was not at the time this research was conducted.

The authors report no other financial or non-financial conflicts of interest.

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lorenz, S., Hull, L. Do All of Us Camouflage? Exploring Levels of Camouflaging and Mental Health Well-Being in the General Population. Trends in Psychol. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43076-024-00357-4

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43076-024-00357-4