Abstract

This article emphasizes the importance of synchronization in changing patients’ dysfunctional patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors to functional ones. Furthermore, the concept of synchronization in psychotherapy is delineated herein, showing its feasibility through the free energy principle. Most sync-oriented publications focus on the therapist-patient relationship. In contrast, this article is focusing on the therapeutic process, especially by analyzing how dysfunctional units—both in an individual’s mind, as well as in social relationships—assemble in synchrony and how psychotherapy helps to disassemble and replace them with functional units. As an example, Gestalt psychology and Gestalt psychotherapy are demonstrated through the lenses of synchronization, supported by diverse case studies. Finally, it is concluded that synchronization is opening a gateway to understanding the change dynamics in psychotherapy and, as such, is worth further study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There is growing interest in synchronization in relation to the therapeutic process (Koole & Tschacher, 2016; Ramseyer & Tschacher, 2011; Reich et al., 2014; Tschacher et al., 2014; Yokotani et al., 2020). This is supported by development in the hard- and software monitoring of synchronization in therapy.Footnote 1 However, most publications focus on the therapist-patient relationship. In contrast, this article advances the field by focusing on the therapeutic process, especially by analyzing how dysfunctional units—both in an individual’s mind, as well as in social relationships—assemble in synchrony and how psychotherapy helps to disassemble and replace them with functional units.

Synchronization

Synchronization is the process of the coordination of events in order to operate a system in unison. Elements can achieve selective (cluster) synchronization if they simultaneously become salient in some manner, and this mechanism is likely used to synchronize elements that are instrumental to the achievement of a goal (Nowak et al., 2020, p. 18).

Synchronization can be described using two different perspectives: at the level of system dynamics and at the level of inter-influence among system elements. Both perspectives represent the binding of dynamics, i.e., the dynamics of one element being dependent on the dynamics of another element (Nowak et al., 2020, p. 6).

In relation to therapy, incompatible elements may be neglected, disregarded, or repressed, or two conflicting mental structures may be created. In both cases, dysfunctional units are assembled: in the first case, leading to the emergence of aggravating unfinished business—a term used in Gestalt therapy (see: Greenberg & Malcolm, 2002; O'Leary & Nieuwstraten 1999); in the second case, the persistence of conflicted mental structures in time may lead to neurotic stress (e.g., Andrews et al., 1993).

To deal effectively with these problems, it is necessary to disassemble dysfunctional units, thereby setting the stage for a reconfiguration that is more adaptive.

Functional and Dysfunctional Units

A functional unit refers to allowing for the creation of temporary structures in unique configurations that are assembled to perform a specific task (Köhler, 1970; Mandler, 1967; Nowak et al., 2020; Tulving, 1968).

Nowak et al. (2020) proposed that the functioning of a system is made possible because of intermittent synchronization, in which sets of elements are assembled and disassembled over time, as demanded by the present function. The elements comprising a substructure are assembled to create a functional unit, which can be observed at different levels of psychological and social reality, from the human brain to minds, groups, and societies. In this vein, to deal effectively with human problems, it is necessary to disassemble dysfunctional patterns, thus setting the stage for a reconfiguration that is more adaptive.

Free Energy Principle

Energy is perceived as an important issue in psychotherapy (e.g., Feinstein, 2008; Gallo, 2004). There are three kinds of human energy mentioned in the literature, as follows:

-

(1)

Energy being a result of metabolism. For example, studies have found that mental effort can be measured in terms of increased metabolism in the brain (Benton et al., 1996; Fairclough & Houston, 2004; Gailliot et al., 2007). Brain metabolism, measured by functional magnetic resonance imaging or positron emission tomography, is a physical correlate of mental activity.

-

(2)

Libidinal energy, primarily mentioned in psychoanalysis as psychic energy produced by the libido (Barratt, 2015; Jung, 1913). For example, Sigmund Freud (1900) used the term “libidinal energy economy” for the dynamic contradictoriness of repression barriers.

-

(3)

The understanding of energy in this article relates to the harmony of a system associated with synchronization.

Synchronization is a natural state in which self-organizing systems strive for a state of minimum energy, according to the free energy principle; an emergent property of this process is synchronization (Ashby, 1962; Friston, 2010; Friston et al., 2006). This relates to all biological systems, including the brain, individuals, and families. It is instrumental for a child’s successful development (Feldman, 2007; Harrist & Waugh, 2002) and an adolescent’s successful social adaptation (Barber et al., 2001). Some authors posit that synchrony is an emergent property of free energy minimization and, in lieu of this, synchronization is a state of a “resting brain” (Palacios et al., 2019).

In groups, synchronization increases the tendency to cooperate and to maintain positive relationships (Tschacher et al., 2014; Wiltermuth & Heath, 2009), while it decreases the occurrence of conflicts and generates efficiency of task groups (Barsade, 2002). On an individual level, individuals tend to like and to have more compassion for those with whom they are synchronized (Hove & Risen, 2009; Moritz, 2017; Valdesolo & DeSteno, 2011), and are also more eager to cooperate with them (Lang et al., 2017; Wiltermuth & Heath, 2009).

The state of synchronization may be temporary, depending on its usefulness. The elements of a system assemble into functional synchronized units and then disassemble when no longer serviceable (Nowak et al., 2020; Ramseyer, 2011). This property is especially important when the temporary synchronized unit is dysfunctional, leading to some impairments, e.g., on a neuronal level, such as in epilepsy (Jiruska et al., 2013; Lehnertz et al., 2009), or on an individual level, e.g., obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) (Özçoban et al., 2014; Tass et al., 2003). On a family level, some sequences of mutually reinforced subsequent actions/reactions may occur, thereby forming destructive patterns (Nowak et al., 2020; Praszkier, 1992).

The Psychotherapeutic Process and Synchronization

Psychotherapy is the use of psychological methods to help a person change and overcome problems in desired ways. It is a collaborative treatment based on the relationship between an individual and a psychologist, grounded in dialog and the provision of a supportive environment that allows the individual to talk openly with someone who is objective, neutral, and nonjudgmental, with the aim of working together to identify and change the thought and behavior patterns that keep the patient from feeling good (Hamlyn, 2007; Wampold, 2019).

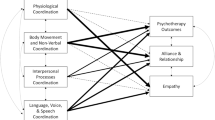

There have been some studies related to synchronization in psychotherapy, though mostly focused on the positive impact of synchronization on the psychotherapist-patient relationship and the way it influences the outcomes of psychotherapy (Koole & Tschacher, 2016; Ramseyer & Tschacher, 2008, 2011; Tschacher et al., 1998, 2014). To date, there have been no studies on the change dynamics in relation to synchronization.

Filling this gap, and using the premise of the synchronization concept, the psychotherapeutic process may be seen as focused on disassembling dysfunctional units and thus creating space for the emergence of functional ones.

Some problems (e.g., neuroses) appear when elements assembled on a lower level (e.g., memories from past experiences) create, at a higher level of awareness, new dysfunctional units. These units usually influence an individual’s cognitive structure, impacting one’s ability to understand oneself, to attribute others’ behaviors, and to perceive the relationships between oneself and others.

Perhaps, the best illustration of psychotherapy as a process of disassembling dysfunctional units and providing space for replacing them with new emergent structures in one’s cognition, emotions, and awareness is Gestalt theory and Gestalt therapy.

Gestalt Psychology and Gestalt Psychotherapy

Presented below are the basic concepts of Gestalt psychology and field theory, followed by a delineation of the application of synchronization to Gestalt theory, concluded with a characterization of the principles of Gestalt therapy.

Gestalt Psychology and Field Theory

Kurt Lewin’s original conception of field theory (Lewin, 2004) was based on Gestalt psychology (Burnes & Cooke, 2012). The basic premise is seeing the situation as a whole (Lewin, 2004); in other words, perceiving functional systems instead of single elements. There are several related principles (Deutsch, 1954; Parlett & Lee, 2005), as follows:

-

(1)

Organization and retroflection: Even small, seemingly irrelevant movements, such as tapping one’s finger on the table, may be significant as a symptom of one or more important mechanisms, e.g., the retroflection of energy. Retroflection occurs when a person turns his/her stored up, mobilized energy back upon himself instead of out into the environment, and tapping may be a signal of a suppressed need for the discharge of retroflected energy.

-

(2)

Contemporaneity: The present time reflects both the past (as it was remembered) and the anticipated future.

-

(3)

Singularity: Each situation is unique and could be seen as a “new opening.”

-

(4)

Changing process: Nothing is fixed and static in an absolute way. For each individual, the field is newly constructed moment by moment; individuals cannot have an identical experience twice.

-

(5)

Possible relevance: No part of the total field can be excluded in advance as irrelevant. Everything in the field is part of the total organization and is potentially meaningful.

-

(6)

The figure–ground construct: In Gestalt psychology, an important concept is the figure–ground theory, which refers to the tendency of a system to simplify a scene into the main object being observed (i.e., the figure) and to educe it from everything else that forms the background (Cherry, 2016; Wertheimer & Riezler, 1944). When a need appears (e.g., hunger), all related images of food, smells, etc., become figures, and the rest of the reality remains in the background. When hunger is appeased, a new functional unit appears, which is a new Gestalt (and it is Gestalt psychology that first introduced the emergence of functional units; see: Nowak et al., 2020), such as admiring the beauty of nature or business challenges, and everything else moves into the background.

Gestalt Theory and Synchronization

This delineated process is synchronous: Gestalts emerge, and after gratification has been removed, space is created for new functional Gestalts, thus forming new functional units. However, in some cases, the existing Gestalt is not fulfilled or gratified, and as such, while new needs become more pressing, it is (semi)moved into the background. The unattained functional unit lingers and retroflects in the background, popping up through some unintended movement (e.g., tapping a finger) or action (e.g., emotions transferred to someone else). This kind of a dysfunctional unit does not integrate and, often unconsciously, shatters synchrony.

An example might be that someone did not tell his father, before he died, that he loved him. This unfulfilled need endures, in the background, throughout the rest of his life, unintentionally influencing various actions. The Gestalt principle of contemporaneity allows the individual to fulfill this need in the present through a dialog with the imagined father sitting on an empty chair (see Gestalt techniques below). In this way, the mental system regains synchrony.

Gestalt Therapy

In Gestalt therapy, the ultimate goal is to achieve a client’s awareness, which includes knowing the environment, taking responsibility for choices, self-knowledge, self-acceptance, and the ability to establish contact with others (Yontef, 1993). Awareness is seen here as both the content and the process, both of which progress to deeper levels as the therapy proceeds (Yontef, idem).

The founder of Gestalt therapy, Fritz Perls, believed that the ultimate goal of psychotherapy is the achievement of a degree of integration that facilitates its own development (Perls, 1992). In the language of this article, this means decomposing the dysfunctional configurations in the patient’s awareness and fostering the process of recomposing them into new functional units.

Perls based his approach on the concept of phenomenological experience (Crocker, 1999; Latner, 2000; Yontef, 1993), i.e., on shifting the awareness from interpretations and attributions (i.e., malfunctioning cognitive units) to experiencing the “here and now,” and in this way, decomposing old dysfunctional cognitive units and recomposing them on a new functional level. This process was delineated by Melnick and Nevis (2005) as follows:

-

Rather than talking about a critical person (e.g., a parent) from a client’s life, a Gestalt therapist might ask him or her to imagine this person in the present (e.g., as if sitting opposite them on an empty chair), or imagining that the therapist is the parent; in both situations, the patient is asked to talk to that person directly in the present.

-

A Gestalt therapist might notice something about the non-verbal behavior or tone of voice of the client; then, he or she might have the client explore or exaggerate this non-verbal behavior and fully experience how this reverberates in their emotions.

-

The Gestalt therapist works with process rather than content, i.e., the “how” rather than the “what.”

Similarly, Gestalt therapy principles were seen by Marcus (1979) as exploring:

-

Contact, especially the “here and now” contact with the therapist.

-

Process, i.e., the flow of the “here and now” behaviors, thoughts, and attributions.

-

Experimentation, e.g., transforming the patient’s verbal account into role-playing.

-

These principles translate into very specific techniques, which Yontef (1993) called “patient focusing:”

-

Stay with it: Whatever you feel, e.g., being sad, just stay with it, try to explore and deepen the feeling, instead of escaping from it.

-

Enactment: Change descriptive narration into action; instead of talking about someone, talk to this person (e.g., imagining him or her sitting on an empty chair opposite them).

-

Exaggerate statements or expressions and connect with associated feelings.

-

Guided fantasy: The patient closes their eyes and imagines metaphorical situations described by the therapist (e.g., “imagine walking up the hill, finding a dark cave; you are entering the cave—what do you feel?” or “You see a door, come close to it, what are your first thoughts?”).

-

Body techniques—for integrating body and mind.

-

Paradoxical techniques, e.g., identifying with both sides of the conflict and speaking from both perspectives (e.g., changing between two chairs, each representing one of the opposing parties).

The Gestalt therapist acts as a “field theory agent:” He/she is not detached from the field, but rather is a part of it (Latner, 2000; Parlett & Lee, 2005), and carries out mutual “investigation” into how the field and its different parts are organized (Clarkson, 2013; Lewin, 2004; Parlett & Lee, 2005). In lieu of this, the therapist analyzes the existing (“here and now”) functional or nonadaptive units (e.g. some synchronized maladjusted sequences), creating an enabling environment that fosters the process of dissolving old, dysfunctional mental units and replacing them with new ones, based on the perception of reality (especially in the “here and now”). The following cases show therapists “in action.”

From the dynamical point of view, these techniques lead to disenabling of the dysfunctional emotional units and assembling new and functional ones; and in that way—achieving a higher synchrony level.

Examples of Gestalt-Style Interventions

The below cases are abbreviated accounts. The first two are from the Gestalt workshops of Eric Marcus, M.D. carried out in Warsaw in the late 1970s. The third refers to the co-author’s (Praszkier, 1992) professional experience as a psychotherapist.

Ann: Discomfort When Focusing on Oneself

In a group session, Ann decided to present her problem. In preparation, she shifted from her comfortable position to an awkward, forward-leaning posture that required muscle tension to be sustained. When she started to talk about her problem, the Gestalt facilitator stopped her and said, “Please don’t move, and fully experience the position you are currently sitting in.” “How does it feel?” he asked.

“I am tense,” Ann responded. The facilitator asked her to relax back into her previous position. Ann sat back, comfortably supported by the back of the chair.

“How do you feel?” asked the facilitator.

“Relaxed,” said Ann.

“Now please sit back in the position you took when you started to present your problem.” Ann again leaned forward to the tense position. The facilitator said, “Ann, please say: ‘When I speak about myself, I must take an uncomfortable position’.”

The group members held their breath as Ann hesitated. Finally, clearly upset, she said in a low voice, “When I speak about myself, I must take an uncomfortable position.” The therapist then asked Ann to repeat this phrase loudly, “When I focus on myself, I must feel uncomfortable!” He asked whether the statement fit her actual feelings.

Ann cried, while the group members remained in total silence, understanding that this was relieving the discharge of previously suppressed emotions. After a while, the Gestalt therapist asked: “When do you feel similar?” Ann responded that this was actually the issue she wanted to raise at the beginning: That with her peers or among her colleagues at work, she always feels tense and stunned, especially when it is her turn to speak up; it even—or especially—happens when she has something important or interesting to say.

This therapeutic experience of enactment and exaggeration solved her problem, as she realized how much she tortured herself whenever focusing on herself or her own ideas. “I will always remember this experience and how I believed that when I speak about myself I must feel uncomfortable.”

The therapist commented that this new experience gave Ann good momentum. At one of the next sessions, Ann volunteered to continue. The therapist asked about her first remembered experience of feeling similar, and this brought back childhood memories. Again, the method was to speak directly to the key people in her life, imagining them sitting across from her—and, in turn, stepping into their shoes to respond to “little Ann.” This inner and often suppressed dialog was enacted at a high-energy level.

In this way, the lingering unfinished and unclosed Gestalts were closed in the “here and now,” in accordance with the contemporaneity principle.

John: Intellectual Shield Covering Anger

John was the most intellectual group member. He talked slowly, weighed his words, and took an unemotional stance. In this way, he was respected, though not very much liked.

During group sessions, John was the last to discuss his problems. When he did speak, he focused on the furthest corner of the ceiling and spoke slowly and without emotion. It came across as a very studied and intellectual account of how he is honest in relationships with people and how this honesty makes others keep him at a distance. At one point, the facilitator interrupted him, “Have you noticed that whenever you talk, you find a spot on the ceiling to talk to? This must be an important place to attract your attention. What is this spot telling you?”.

John looked unnerved and flustered, hesitant to respond. The facilitator continued, “Could you imagine being this spot and talking to John?” John stared at the therapist and then back at the ceiling. Finally, a bit jittery, he started to talk: “I am a neutral spot, I keep your attention so you don’t become emotional; I am your resource to stay balanced.” The facilitator asked John to reply to what the spot on the ceiling told him. John looked even more agitated. “Thank you for being my guardian. Without you…. without you…. I would become furious,” he said in a faltering voice, his hands and legs shaking slightly.

He looked at the therapist, who said, “John, try to be furious then; see what it looks like. Take a pillow and hit the sofa.” John tried. “Harder, John, let all of that anger out of you, and shout out whatever comes to your mind.”

John became furious, hitting the sofa as hard as he could and yelling “I hate you, I hate you.” Finally, he threw the pillow away and, looking a bit confused, sat down. It was the first moment the group saw “the real” John—as per their comments in a feedback session, they witnessed John being natural and being human. Some said that during the lunch break that followed this episode, they wanted to socialize with John, who reacted in a new way, without his usual intellectual shield. After the break, John confirmed that he felt much closer to people.

In one of the next sessions, John came forward, willing to explore where his unwanted anger came from. The therapist asked about his first memories of feeling anger. This apparently raised John’s tension levels. Finally, he said that he remembered being six years old, beset by other children on the playground, especially by the girl he liked the most. At that time, he did not react. He did not even tell his parents, because he was shy to admit that the other children were after him. The therapist asked if there was a specific child he remembered; it was Mary, the girl he actually liked the most. The therapist asked John to imagine Mary sitting on the empty chair in front of him and to talk to her. Through a tense and painful process, John finally opened up and talked to Mary, saying how much he both liked and hated her and that he wanted to hit her in the present moment. The therapist gave John a pillow and prompted him to hit the empty chair and the imaginary Mary. He also told John to speak and shout while hitting the pillow. After this high-energy experience, John became calm and reflective, as well as visibly more relaxed on a physical level.

A Tedious Family

Sessions with this family were prompted by the 16-year-old daughter Juliet’s risk of developing anorexia. In this case, medical support was secured. There were also several preceding individual sessions with the daughter that indicated family communication problems.

During the first few family meetings, the progress gradually slowed to the point that it seemed stuck. The family members communicated in a succinct and formal way, spirited only by Juliet’s problems. Analyzing this case with his colleagues, the therapist noted that there was no real vitality in this family, only routine and tedious patterns. It seemed that the daughter and her younger brother expected more vibrant relationships, and implicitly, that both parents would appreciate such a change as well. In this case, their lack of “fire” was understood as a lack of interest.

The psychotherapist thought that without an occasional burst of joy and “craziness,” relationships usually remain limited to formal patterns, becoming overwhelmingly boring and meaningless. The issue was how to bring into the family some vibrant humor and creativity—a daunting challenge given that “bringing in humor” seemed like an oxymoron (as humor is usually spontaneous). Finally, the idea was to use the Gestalt technique of guided fantasy.

During the next session, the therapist suggested that everybody close their eyes and follow his instructions: “Imagine that your family is sitting at the dinner table. Who sits where? Who says what? Now imagine that the person on your right is doing something really crazy. What is it?”.

There was complete silence. After a while, with their eyes still closed, some of them started to giggle. “Now imagine that the person to your left is doing something really crazy.” The chuckles turned into laughs. The therapist asked the family to open their eyes and to share with one another what they had envisioned. They kept laughing, feeling relaxed and spontaneously talking to one another.

The son imagined their father putting the plate of noodles over his head and the noodles slowly creeping down his face. The father imagined his wife putting her favorite china cat sculpture into a cage. Juliet imagined her brother climbing up onto their wardrobe and loudly reading poems from there (the boy hated poems), and so forth. They could not stop laughing, and continued to share their images. The family left the therapist’s office sharing their ridiculous visions, especially those of the usually formal and humorless father with noodles on his head.

This experience triggered a different communication style at home. The images remained in their memories as “implants,” paving the way to more spontaneous communication. Funny ideas and jokes emerged; they changed their usual patterns, hung out together, went for outdoor treks, etc. This, in a feedback loop, had an influence on Juliet, alleviating her feeling of isolation and lack of acceptance and releasing her tension, thereby eradicating the root causes of her over-fasting.

Summary

The curative effects of Gestalt techniques such as enactment, “stay with it,” empty chair dialog, exaggeration, and guided fantasy seem apparent. Ann took her first step by identifying, on the emotional and bodily levels, her previous dysfunctional pattern that merged self-focus with discomfort. The next level of intervention led her to relive her early memories and to explore the circumstances supporting the occurrence of such a conjunction. Her lingering dysfunctional units were dismantled, opening her up to new experiences, i.e., building functional units around self-acceptance and self-reliance.

John was seemingly unwilling to accept the interpretation of him cutting himself off from his emotions and, instead, over-intellectualizing. However, the Gestalt enactment techniques contributed to a non-defensive, emotional way of gaining insight into his process of over-intellectualization that served as a shield, protecting him from his anger, which he was previously hiding from his own cognition. This new insight, together with releasing his emotions in public, gained him attention and was reinforced by positive feedback for being perceived as much more natural and real.

Through the guided fantasy technique, Juliet’s family found a way to change their usual patterns to more vibrant, real, and joyful experiences. The images of family members doing something funny shattered the previous dysfunctional system that was maintaining only formal, a-emotional relationships; also, these images paved the way for a new communication mode that turned into a functional unit, thereby bonding the family.

Previously, the family was paradoxically “bonded” by Juliet’s anorectic problems—the only field where they shared true emotions. The family systems theory indicates that symptoms often play a “positive” role by providing a platform for vibrant communication and, in lieu of this, offering protection from other threats, e.g., family disintegration (Keeney, 1983; Praszkier, 1992). The new functional unit re-bonded the family, creating a new way of synchronization.

In all those cases, there was demonstrated a process of achieving a new, adaptive synchrony level, through dismantling the dysfunctional emotional and behavioral units and assembling more functional ones.

Discussion

Fabian Ramseyer and Wolfgang Tschacher from Bern University asserted that synchronization is a pervasive concept relevant to diverse domains in physics, biology, and the social sciences. Are they right in positing that synchrony is also pivotal for psychotherapeutic processes? It seems that it is, considering the growing volume of articles in this field across the last two decades (e.g., Koole & Tschacher, 2016; Ramseyer & Tschacher, 2006; Reich et al., 2014; Yokotani et al., 2020).

The premise of synchronization and the assembly and disassembly of dysfunctional units seems cut out for Gestalt therapy: The dysfunctional units of unfinished business (Greenberg & Malcolm, 2002; Lubinski & Thompson, 2017; O'Leary & Nieuwstraten 1999) are being addressed—according to the Gestalt contemporaneity principle—in the present, as they are present in the present.

Other than the Gestalt therapeutic approaches that refer to the essential role of synchronization, e.g., the psychoanalytic concept of separation, individuation has also been analyzed under the premise of synchronization (Moon & Bahn, 2016); additionally, family systems therapy has been presented through the lens of synchronization (Nowak et al., 2020).

A caveat is that the therapeutic process often is more complicated than in the cases demonstrated in this article. The presented examples were selected as to best portray the issues of synchronization in Gestalt Therapy.

The method used in this article is to delineate the core theoretical concept through case studies. This article is only a first step into deepening our knowledge on the role of synchronization in psychotherapy. The conclusions thus far indicate the value of further study in this direction.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Andrews, G., Page, A. C., & Neilson, M. (1993). Sending your teenagers away: Controlled stress decreases neurotic vulnerability. Archives of General Psychiatry, 50(7), 585–589. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820190087009

Ashby, W. R. (1962). Principles of the self-organizing system. In H. Von Foerster & G. W. Zopf (Eds.), Principles of Self-Organization: Transactions of the University of Illinois Symposium (pp. 255–278). Pergamon Press.

Barber, J., Bolitho, F., & Bertrand, L. (2001). Parent-child synchrony and adolescent adjustment. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 18(1), 5–64. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026673203176

Barsade, S. G. (2002). The ripple effect: Emotional contagion and its influence on group behavior. A Dministrative Science Quarterly, 47(4), 644–675. https://doi.org/10.2307/3094912

Benton, D., Parker, P. Y., & Donohoe, R. T. (1996). The supply of glucose to the brain and cognitive functioning. Journal of Biosocial Science, 28(4), 463–479. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0021932000022537

Barratt, B. B. (2015). On the mythematic reality of libidinality as a subtle energy system: Notes on vitalism, mechanism, and emergence in psychoanalytic thinking. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 32(4), 626–644. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034973

Burnes, B., & Cooke, B. (2012). Kurt Lewin’s field theory: A review and re-evaluation. International Journal of Management Reviews, 15(4), 408–425. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2012.00348.x

Cherry, K. (2016). What is figure-ground perception? Very well. Retrieved 26.10.16 from: https://www.verywell.com/what-is-figure-ground-perception-2795195.

Clarkson, P. (2013). Gestalt Counselling in Action. SAGE Publications.

Crocker, S. (1999). A well-lived life; Essays in Gestalt Therapy. Gestalt Press.

Deutsch, M. (1954). Field Theory in Social Psychology. In: Lindzey, G. & Aronson, E. The Handbook of Social Psychology, vol. 1, pp. 412–487. Hoboken, NJ, Wiley.

Fairclough, S. H., & Houston, K. (2004). A metabolic measure of mental effort. Biological Psychology, 66(2), 177–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2003.10.001

Feinstein, D. (2008). Energy psychology: A review of the preliminary evidence. Psychotherapy Theory Research & Practice, 45(2), 199–213. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.45.2.199

Feldman, R. (2007). Parent-infant synchrony and the construction of shared timing; physiological precursors, developmental outcomes, and risk conditions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48(3–4), 329–354. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01701.x

Freud, S. (1900). The Interpretation of Dreams. Standard Edition, 4–5, 1–627.

Friston, K., Kilner, J., & Harrison, L. (2006). A free energy principle for the brain. Journal of Physiology, 100(1–3), 70–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphysparis.2006.10.001

Friston, K. (2010). The free-energy principle: A unified brain theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11, 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2787

Gailliot, M. T., Baumeister, R. F., DeWall, C. N., Maner, J. K., Plant, E. A., Tice, D. M., & Brewer, L. E. (2007). Self-control relies on glucose as a limited energy source: Willpower is more than a metaphor. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(2), 325–336. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.2.325

Gallo, F. P. (2004). Energy psychology: Explorations at the interface of energy, cognition, behavior, and health. CRC Press.

Greenberg, L. S., & Malcolm, W. (2002). Resolving unfinished business: Relating process to outcome. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(2), 406–416. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.70.2.406

Hamlyn, S. (2007). An Historical Overview of Psychotherapy. In C. Lister-Ford (Ed.), A Short Introduction to Psychotherapy (pp. 3–31). SAGE Publications.

Harrist, A. W., & Waugh, R. M. (2002). Dyadic synchrony: Its structure and function in children’s development. Developmental Review, 22(4), 555–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0273-2297(02)00500-2

Hove, M. J., & Risen, J. L. (2009). It’s all in the timing: Interpersonal synchrony increases affiliation. Social Cognition, 27(6), 949–960. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2009.27.6.949

Jiruska, P., de Curtis, M., Jefferys, J. G. R., Schevon, C. A., Schiff, S. J., & Schindler, K. (2013). Synchronization and desynchronization in epilepsy: Controversies and hypotheses. The Journal of Physiology, 591(Pt 4), 787–797. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2012.239590

Jung, C. G. (1913). The Theory of Psychoanalysis. The Psychoanalytic Review, 1(1), 1–40.

Keeney, B. (1983). Aesthetics of Change. The Guilford Press.

Koole, S. L., & Tschacher, W. (2016). Synchrony in psychotherapy: A review and an integrative framework for the therapeutic alliance. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 862. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00862

Köhler, W. (1970). Gestalt psychology: An introduction to new concepts in modern psychology. WW Norton & Company.

Lang, M., Bahna, V., Shaver, J. H., Reddish, P., & Xygalatas, D. (2017). Sync to link: Endorphin-mediated synchrony effects on cooperation. Biological Psychology, 127, 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2017.06.001

Latner, J. (2000). The Theory of Gestalt Therapy. In E. Nevis (Ed.), Gestalt Therapy: Perspectives and Applications (pp. 13–56). Gestalt Press.

Lehnertz, K., Bialonski, S., Horstmann, M. T., Kruga, D., Rothkegel, A., Staniek, M. & Wagner, T. (2009). Synchronization phenomena in human epileptic brain networks. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 183(1): 30 42–48 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.05.015.

Lewin, K. (2004). Resolving social conflicts. Field theory in social science. American Psychological Association.

Lubinski, D., & Thompson, T. (2017). Functional units of human behavior and their integration: A dispositional analysis. In M. D. Zeller & T. Thompson (Eds.), Analysis and Integration of Behavioral Units (pp. 275–314). Routledge.

Mandler, G. (1967). Organization and memory. Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 1, 327–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-7421(08)60516-2

Marcus, E. (1979). Gestalt Therapy and Beyond; an Integrated Mind-Body Approach. Meta Publications.

Melnick, J., & Nevis, S. M. (2005). Gestalt Therapy Methodology. In A. L. Woldt & S. M. Toman (Eds.), Gestalt Therapy, History, Theory, and Practice (pp. 101–116). Sage Publications.

Moon, D. S., & Bahn, H. B. (2016). The concept of synchronization in the process of separation-individuation between a parent and an adolescent. Psychoanalysis, 27, 35–41. https://doi.org/10.18529/psychoanal.2016.27.2.35

Moritz, K. (2017). When you like someone, your brain waves sync up with theirs. Rewire. Retrieved April 21, 2020 from: www.rewire.org/living/brain-waves-sync.

Nowak, A., Vallacher, R., Rychwalska, A., Praszkier, R., & Żochowski, M. (2020). In Sync: The emergence of function in minds, groups, and societies. New York, NY: Springer.

O’Leary, E., & Nieuwstraten, I. M. (1999). Unfinished business in gestalt reminiscence therapy: A discourse analytic study. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 12(4), 395–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515079908254108

Özçoban, M. A., Kara, S., Tan, O. & Aydın, S. (2014). Investigation the level of neural synchronization by using global field synchronization method in Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. 2014 18th National Biomedical Engineering Meeting, IEE.

Palacios, E. R., Isomura, T., Parr, T., & Friston, K. (2019). The emergence of synchrony in networks of mutually inferring neurons. Scientific Report, 9, 6412. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-42821-7

Parlett, M., & Lee, R. G. (2005). Contemporary Gestalt therapy: Field theory. In L. Ansel Woldt & S. M. Toman (Eds.), Gestalt Therapy: History, Theory, and Practice (pp. 41–63). Sage Publications.

Perls, F. S. (1992). Ego, Hunger and Aggression. The Gestalt Journal Press.

Praszkier, R. (1992). Change without change; the ecology of family problems [Zmieniać nie zmieniając; ekologia problemów rodzinnych]. Warszawa, WSiP.

Ramseyer, F. (2011). Nonverbal synchrony in psychotherapy: Embodiment at the level of the dyad. In: Tschacher, W. & Bergomi, C. (Eds.) The Implications of Embodiment: Cognition and Communication, pp 193–207. Charlottesville: Imprint Academic.

Ramseyer, F. T. (2019). Motion Energy Analysis (MEA). A primer on the assessment of motion from video. Journal of Counseling Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000407.

Ramseyer, F., & Tschacher, W. (2006). Synchrony: A Core Concept for A Constructivist Approach to Psychotherapy. Constructivism in the Human Sciences, 11(1–2), 150–171.

Ramseyer, F., & Tschacher, W. (2008). Synchrony in Dyadic Psychotherapy Sessions. In S. Vrobel, O. E. Rossler, & T. Marks-Tarlow (Eds.), Simultaneity: Temporal structures and observer perspectives (pp. 329–347). World Scientific.

Ramseyer, F., & Tschacher, W. (2011). Nonverbal synchrony in psychotherapy: Coordinated body-movement reflects relationship quality and outcome. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(3), 284–295. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023419

Reich, C. M., Berman, J. S., Dale, R., & Levitt, H. M. (2014). Vocal synchrony in psychotherapy. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 33(5), 481–494. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2014.33.5.481

Tass, P., Klosterkötter, J., Schneider, F., Lenartz, D., Koulousakis, A., & Sturm, V. (2003). Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Development of Demand-Controlled Deep Brain Stimulation with Methods from Stochastic Phase Resetting. Neuropsychopharmacology, 28, S27–S34. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300144

Tschacher, W., Scheier, C., & Grawe, K. (1998). Order and pattern formation in psychotherapy. Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, and Life Sciences, 2(3), 195–215. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022324018097

Tschacher, W., Rees, G., & Ramseyer, F. (2014). Nonverbal synchrony and affect in dyadic interactions. Frontiers in Psychology, 5(1323), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01323

Tulving, E. (1968). Theories used in free recall. In T. R. Dixon & D. L. Horton (Eds.), Verbal Behavior and General Behavior Theory (pp. 2–36). Prentice Hall.

Yokotani, K., Gen, T., & Wakashima, K. (2020). Nonverbal synchrony of facial movements and expressions predict therapeutic alliance during a structured psychotherapeutic interview. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 44(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-019-00319-w

Yontef, G. (1993). Awareness, Dialogue, and Process, essays on Gestalt therapy. The Gestalt Journal Press.

Valdesolo, P., & DeSteno, D. (2011). Synchrony and the Social Tuning of Compassion. Emotion, 11(2), 262–266. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021302

Wampold, B. E. (2019). The Basics of Psychotherapy (An Introduction to Theory and Practice). American Psychological Association.

Wertheimer, M., & Riezler, K. (1944). Gestalt theory. Social Research, 11(1), 78–99.

Wiltermuth, S. S., & Heath, C. (2009). Synchrony and Cooperation. Psychological Science, 20(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02253.x

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Volunteer Editor Paige Vanleer for her important contribution. This article is assigned to the Robert B. Zajonc Institute for Social Studies, University of Warsaw.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Praszkier, R., Nowak, A. In and Out of Sync: an Example of Gestalt Therapy. Trends in Psychol. 31, 75–88 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43076-021-00133-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43076-021-00133-8