Abstract

Dolphins in the wild cooperate to find food, gain and maintain access to mating partners, look after their young ones, or for the sheer joy of play. Under human care, environmental enrichments provide mental and physical stimulation and opportunities for the dolphins to practice their natural abilities. In this review, I focus on a set of enrichment devices we designed for cooperative problem-solving. They allowed the dolphins to utilize and improve their cognitive skills, leading to improved socialization within the group. While the devices provided appropriate challenges to the dolphins, they also allowed the investigation of the impact of demographic and social factors on the cooperative actions. We found that age and relatedness had no impact on cooperation; in turn, cooperation increased with group size. In addition, during the use of these cognitive enrichments, partner preference and intersexual differences were revealed in cooperative actions. The novel multi-partner devices were not only used by dolphin pairs but also by dolphin trios and quartets, providing evidence for group-level cooperation. In addition, a novel food-sharing device was used prosocially by dolphin pairs. Finally, the introduction of these cognitive enrichments leads to measurable short- and long-term welfare improvement. Thus, the use of these cognitive enrichments paired with systematic data collection bridged science with welfare. Future studies will investigate intersexual differences in independent groups, the emergence and function of cooperative interactions, and the socio-dynamics using cognitive enrichments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cooperation can be defined as two or more individuals working together for a common goal (Boesch and Boesch 1989). Dolphins in the wild cooperate for multiple reasons. They work together to find and catch food, developing a striking variety of group hunting tactics, such as strand feeding (Jiménez and Alava 2015) and mud ring feeding (Ramos et al. 2022), and cooperative prey herding (Benoit-Bird and Au 2009). They were even observed to take up different roles during group hunting (Gazda et al. 2005). Females have also been documented to provide alloparental care (Herzing 1997; Martin and Da Silva 2018; New et al. 2013). In contrast, male dolphins recruit allies to capture and maintain access to females (Connor and Krützen 2015). Finally, dolphins have been observed to play socially, for example, passing a piece of sargassum (Kaplan et al. 2018) or a ball (Ikeda et al. 2018).

Under human care, environmental enrichment devices (EEDs) can provide both mental and physical stimulation (Kuczaj et al. 1998; Makecha and Highfill 2018). They increase behavior diversity, reduce stereotypy, and enhance the display of species-specific behaviors. Their importance in zoos and aquariums has been well documented (Harley et al. 2010; Kuczaj et al. 2002; Mellen and MacPhee 2001; Shepherdson et al. 2012). The design of the appropriate tools has been in the focus of several studies (Eskelinen et al. 2015; Fabienne and Helen 2012; Mason et al. 2007). EEDs are often categorized by their function, such as visual, olfactory, auditory, structural, tactile, social, or food-based enrichments (Hoy et al. 2010). A special category, cognitive enrichment, provides problem-solving challenges, i.e., opportunities to practice one’s innate cognitive skills (Clark 2011; 2013; Clark et al. 2013).

Dolphins in the wild have been reported to cooperate to solve all major challenges in their life successfully (finding food, finding mates, and raising their young ones) and even to play socially. Thus, designing EEDs for cooperative use was a logical idea. The devices not only provided adequate enrichment to our dolphins, but they also proved to be important tools to investigate the underlying mechanism of cooperation and their long-term welfare impact on the dolphins. This brief review summarizes our observations during the testing use of a set of cooperative enrichment devices at Ocean Park Hong Kong (OPHK).

Mutual cooperation by dolphin pairs

The first cooperative enrichment device consisted of a PVC tube with two caps equipped with rope handles. The device was filled with ice and fish each time before given to the dolphins. It allowed simultaneous interaction for pairs of dolphins. The device could be opened by synchronous pull of the rope handles, allowing access to its content. The device was tested in three facilities: at Dolphin Cove, Florida (Kuczaj et al. 2015), at Roatan Institute for Marine Sciences, Honduras (Bagley et al. 2020), and at Ocean Park Hong Kong (Matrai et al. 2021a; b; Matrai et al. 2020). In the first test by Kuczaj and his colleagues (2015), the device was introduced to a mixed group of three male and three female dolphins. The males successfully opened the device in cooperation. As the males monopolized the device during the sessions, the females’ device-related behaviors could not be tested (Kuczaj II et al. 2015). Bagley and her colleagues tested the same device with five pairs of dolphins. None of the pairs opened the device in cooperation; however, they found a correlation between the dolphins’ device-related behaviors and their personalities (Bagley et al. 2020).

The first devices used at Ocean Park Hong Kong followed the same design. Age in our same-sex group of male and female dolphins (Tursiops aduncus) ranged between 1 and 42 years, and the groups consisted of 4–8 dolphins. No correlation was found between age and cooperative success (cooperative opening of the device) or relatedness and cooperative success. However, there was a sharp difference between the cooperative success of the sexes. Males were four times more successful in opening the device in cooperation than female dolphins (Matrai et al. 2021a; 2022a). Females were also interested in the devices and interacted with them throughout the experiment, but they did it in a solo, taking turn in playing with it. While both sexes have been observed to participate in cooperative actions in the wild, the observed sex differences in our study may reflect on the males’ natural alliance formation tendencies (Connor et al. 2017; Connor and Krützen 2015; Gerber et al. 2021; Krützen et al. 2003; Nishita et al. 2017).

Building on the initial cooperative success of the male groups, we were interested in the drivers of male cooperation. Thus, additional group testing and pair-wise testing were conducted. The groups included four, five, or six dolphins with a single or two devices. The number of cooperative openings increased with group size. Out of the six dolphins, five showed active interest in the device. These five dolphins were also tested pair-wise, systematically. All 10 possible pairs succeeded in opening the device cooperatively. However, during the group setting, some pairs were recorded to cooperate more often, while others were never observed to cooperate during group testing. These findings suggest that when multiple partners are available, the dolphins may prefer some of them over others (Matrai et al. 2021b).

Male dolphins were not only more successful in opening the devices cooperatively, but they also invented a novel behavior, cooperative play that was never observed in females. During cooperative play, the male dolphins held the device between them and swam in synchrony. They kept the same speed, direction, and rhythm of breathing. Cooperative play is regarded as a spontaneous, affiliative behavior, which we observed almost every session, mainly after the opening events, i.e., when the device was already emptied. There was a strong correlation between participating in the opening and the playing. Hence, we consider the opening and play part of the same behavior chain rather than independent behaviors (Matrai et al. 2021b). Alliance formation has been linked with reproductive benefits (Frère et al. 2010; Krützen et al. 2003), and we assume cooperative play is likely to provide opportunities for obtaining new or maintaining existing relations.

Multi-partner cooperative enrichments

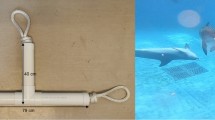

The successful introduction of the two-way device and the dolphins’ inclination of cooperation inspired novel designs. Our team was interested in investigating if the recorded cooperative actions were only possible by dolphin pairs or, if an opportunity was given, more animals would cooperate, simultaneously. In the wild, group-level collaboration has been observed during group hunting (Benoit-Bird and Au 2009) or social play (Bel’kovich et al. 1991). Therefore, two multi-player devices were built: one with a T- and another with a TT-shape, allowing simultaneous interactions for three and four dolphins, respectively (Matrai et al. 2022). Prior to our experiment, cooperative enrichments were only designed for dolphin pairs (Kuczaj II et al. 2015; Yamamoto et al. 2019). Thus, these novel devices opened an interesting new avenue for investigating within-group cooperation and socio-dynamics by focusing on multiple individuals at the same time.

With more handles available, dolphin trios and even quartets were observed to cooperate. Cooperative opening of the devices in males was most often observed by pairs: 70% with the T-shape device and 50% with the TT-shape device. However, 30% of the T-shape and 40% of the TT-shape openings were documented with trios. Finally, 10% of the TT-shape openings were observed with a dolphin quartet (Matrai et al. 2022). The two multi-partner devices were also tested with a group of female dolphins. While the dolphins’ interest remained high, similarly to the two-way device, their cooperative opening success rate remained one-third of that of the males. Moreover, in females, only pairs, but no trios or quartets, were observed to participate in cooperative opening (unpublished data). These findings further support sex differences in cooperative tendencies in dolphins in favor of males.

Multi-player cooperation was also observed during cooperative play in males, but never in females. The males spent the most of the experimental time playing cooperatively with the devices, 65% as pairs, 22% as trios, and 6% as quartets. During these interactions, the participating dolphins swam in synchrony while holding the device, just like with the two-way device. However, with the multi-partner devices, we could observe synchronization of up to four dolphins, something that we have never observed with any other enrichments. Moreover, similar to our findings with the two-way device, the dolphins showed preference for certain partners. The pairs that were observed to spend most time together were also more likely to be part of the same trio or quartet (Matrai et al. 2022).

Prosocial food-sharing

A modified version of the two-way enrichment device was designed for testing prosocial food-sharing. The device contained an internal structure which held five pieces of fish in place and a rubber band that kept the device closed. The device was tied to the poolside with one handle, while the other was available to the dolphins to interact with. The fish could be retrieved if one dolphin pulled the handle (actor) and kept the device open for another dolphin (recipient) to access the fish. Male dolphins successfully retrieved one-third of the fish in a prosocial manner. Furthermore, male dolphins showed stable role preferences over the sessions, independent from their age and relatedness (Matrai et al., submitted).

Cooperative enrichments for improving welfare

While there were obvious signs that the dolphins apparently enjoyed interacting with the cooperative enrichment devices, we were interested in how much it influenced their behavior outside of the research sessions, and we also aimed at a more objective measure on their welfare. Seven welfare indicators were monitored in a three-year, long-term study with a group of male dolphins. These were the same animals that participated in the above-mentioned cooperative enrichment studies. Research sessions were conducted twice weekly. The seven welfare indicators included five positive (Play with water, Play with enrichment, Social play, Synchronous play, and Tactile interactions) and two potential negative welfare indicators (Aggression and Potential stereotypy). The presence and the absence of the welfare indicators were recorded daily for each animal by the care team. The short-term impact of the enrichment was investigated by comparing the occurrence of the seven indicators between Session days (when the cognitive enrichments were utilized) and Non-session days (only regular enrichments were used). The long-term analysis investigated the trends in these welfare indicators over the three-year period.

The analyses revealed that ‘Play with enrichment’, ‘Affiliative tactile’,‘Social play,’ and ‘Synchronous swim’ were significantly higher, while ‘Aggression’ was significantly lower on Session days than on Non-session days. Moreover, the social network analysis further supported our findings, showing a decrease in aggressive interactions on Session days. The positive welfare indicators showed an increasing trend over the 36 months, while the negative welfare indicators showed a decreasing trend over the observation period (Matrai et al. 2024; 2022a).

Undoubtedly, the generalizability of these findings are hindered by having only a single group tested with no control group. Nonetheless, these experiments provide a basis for future studies, including collaborations with other institutions.

Conclusions for future directions

Cognitive enrichments provide valuable opportunities for linking science and welfare, emphasizing the importance of appropriate designs. The dolphins’ natural ability for collaborative problem-solving and their flexibility in execution make cooperative enrichment devices perfect for the task. Our devices were built from commonly available, inexpensive materials. They can be easily adapted in any facility around the world. Our studies paved the way for further investigations on the long-term cooperative trends. The social arrangement of dolphins under human care changes over time. As young individuals become mature, they move to other groups. Older individuals reach their end of life, and new dolphins are born. The repeated use of the cognitive enrichment devices allows us to investigate the impact of the changes in the social network on individual (maybe even lifelong) trends in alliance formation and maintenance and the development of social skills of young individuals.

We also aim to extend our investigations by involving other zoos and aquariums. The relative long-term application of our devices at OPHK has provided us with a unique insight into our dolphins’ social life. Our findings are currently limited to one facility and can only be interpreted with caution. However, we hope that our efforts and the proven welfare benefits of the cognitive enrichments will inspire other facilities to join the program. A multi-facility collaboration would provide valuable opportunities for comparison between different dolphin groups and species. Ultimately, it would allow to evaluate whether the trends documented in OPHK are unique to our dolphin group or could be observed across the species or even multiple species.

Finally, testing in the aquarium contributes to our understanding of social behaviors and dynamics in cetaceans in the wild, e.g., the socio-cognitive skills cooperation requires and the function and emergence of cooperation.

References

Bagley KC, Winship K, Bolton T, Foerder P (2020) Personality and affiliation in a cooperative task for bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) dyads. Int J Comp Psychol. https://doi.org/10.46867/ijcp.2020.33.00.05

Bel’kovich VM, Vanova EE, Kozarovitsky LB, Novikova EV, Kharitonov SP (1991) Dolphin play behavior in the open sea. In: Pryor K, Norris KS, (eds) Dolphin societies: discoveries and puzzles, University of California Press, Berkeley, pp 67–77

Benoit-Bird KJ, Au WWL (2009) Cooperative prey herding by the pelagic dolphin, Stenella longirostris. J Acoust Soc Am 125:125–137. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.2967480

Boesch C, Boesch H (1989) Hunting behavior of wild chimpanzees in the Taï national park. Am J Phys Anthropol 78:547–573. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.1330780410

Clark FE (2011) Great ape cognition and captive care: can cognitive challenges enhance well-being? Appl Anim Behav Sci 135:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2011.10.010

Clark FE (2013) Marine mammal cognition and captive care: a proposal for cognitive enrichment in zoos and aquariums. J Zoo Aquar Res 1:1–6. https://doi.org/10.19227/jzar.v1i1.19

Clark FE, Davies SL, Madigan AW, Warner AJ, Kuczaj SA II (2013) Cognitive enrichment for bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus): evaluation of a novel underwater maze device. Zoo Biol 32:608–619. https://doi.org/10.1002/zoo.21096

Connor RC, Cioffi WR, Randic S, Allen SJ, Watson-Capps J, Krutzen M (2017) Male alliance behaviour and mating access varies with habitat in a dolphin social network. Sci Rep 7:46354. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep46354

Connor RC, Krützen M (2015) Male dolphin alliances in shark bay: changing perspectives in a 30 year study. Anim Behav 103:223–235

Eskelinen HC, Winship KA, Borger-Turner JL (2015) Sex, age, and individual differences in bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in response to environmental enrichment. Anim Behav Cognit 2:241–253. https://doi.org/10.12966/abc.08.04.2015

Fabienne D, Helen B (2012) Assessing the effectiveness of environmental enrichment in bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus). Zoo Biol 31:137–150. https://doi.org/10.1002/zoo.20383

Frère C, Krützen M, Mann J, Watson-Capps J, Tsai Y, Patterson E, Connor R, Bejder L, Sherwin W (2010) Home range overlap, matrilineal and biparental kinship drive female associations in bottlenose dolphins. Anim Behav 80:481–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2010.06.007

Gazda SK, Connor RC, Edgar RK, Cox F (2005) A division of labour with role specialization in group-hunting bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) off Cedar Key, Florida. Proc Biol Sci 272:135–140. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2004.2937

Gerber L, Wittwer S, Allen SJ, Holmes KG, King SL, Sherwin WB, Wild S, Willems EP, Connor RC, Krutzen M (2021) Cooperative partner choice in multi-level male dolphin alliances. Sci Rep 11:6901. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-85583-x

Harley HE, Fellner W, Stamper MA (2010) Cognitive research with dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) at disney’s the seas: a program for enrichment, science, education, and conservation. Int J Comp Psychol 23:331–343

Herzing DL (1997) The life history of free-ranging atlantic spotted dolphins (Stenella frontalis): age classes, color phases, and female reproduction. Mar Mamm Sci 13:576–595. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.1997.tb00085.x

Hoy JM, Murray PJ, Tribe A (2010) Thirty years later: enrichment practices for captive mammals. Zoo Biol 29:303–316. https://doi.org/10.1002/zoo.20254

Ikeda H, Komaba M, Komaba K, Matsuya A, Kawakubo A, Nakahara F (2018) Social object play between captive bottlenose and Risso’s dolphins. PLoS ONE 13:e0196658. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196658

Jiménez PJ, Alava JJ (2015) Strand-feeding by coastal bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in the Gulf of Guayaquil, Ecuador. Lat Am J Aquat Mamm 10:33–37. https://doi.org/10.5597/lajam00191

Kaplan DJ, Melillo-Sweeting K, Reiss D (2018) Biphonal calls in atlantic spotted dolphins (Stenella frontalis): bitonal and burst-pulse whistles. Bioacoustics 27:145–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/09524622.2017.1300105

Krützen M, Sherwin WB, Connor RC, Barré LM, Casteele TVd, Mann J, Brooks R (2003) Contrasting relatedness patterns in bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops sp.) with different alliance strategies. Proc R Soc B: Biol Sci 270:497–502. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2002.2229

Kuczaj S II, Winship K, Eskelinen H (2015) Can bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) cooperate when solving a novel task? Anim Cogn 18:543–550

Kuczaj S, Lacinak T, Fad O, Trone M, Solangi M, Ramos J (2002) Keeping environmental enrichment enriching. Int J Comp Psychol 15:127–137

Kuczaj SA, Lacinak CT, Turner TN (1998) Environmental enrichment for marine mammals at sea world. In: Shepherdson DJ, Mellen JD, Hutchins M (eds) Second nature: environmental enrichment for captive animals, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, pp 314–328

Makecha RN, Highfill LE (2018) Environmental enrichment, marine mammals, and animal welfare: a brief review. Aquat Mamm 44:221–230. https://doi.org/10.1578/AM.44.2.2018.221

Martin AR, Da Silva VMF (2018) Reproductive parameters of the Amazon river dolphin or boto, Inia geoffrensis (Cetacea: Iniidae); an evolutionary outlier bucks no trends. Biol J Lin Soc 123:666–676. https://doi.org/10.1093/biolinnean/bly005

Mason G, Clubb R, Latham N, Vickery S (2007) Why and how should we use environmental enrichment to tackle stereotypic behaviour? Appl Anim Behav Sci 102:163–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2006.05.041

Matrai E, Gendron SM, Boos M, Pogány Á (2024) Cognitive group testing promotes affiliative behaviors in dolphins. J Appl Anim Welfare Sci. 27:165-179. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888705.2022.2149267

Matrai E, Kwok ST, Boos M, Pogány Á (2021a) Cognitive enrichment device provides evidence for intersexual differences in collaborative actions in Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins. Anim Cognit 24:1215–1225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-021-01510-7

Matrai E, Kwok ST, Boos M, Pogány Á (2021b) Group size, partner choice and collaborative actions in male Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops aduncus). Anim Cognit 25:179–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-021-01541-0

Matrai E, Kwok ST, Boos M, Pogány Á (2022) Testing use of the first multi-partner cognitive enrichment devices by a group of male bottlenose dolphins. Anim Cogn 25:961–973. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-022-01605-9

Matrai E, Ng AKW, Chan MMH, Gendron SM, Dudzinski KM (2020) Testing use of a potential cognitive enrichment device by an Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops aduncus). Zoo Biol 39:156–167. https://doi.org/10.1002/zoo.21536

Mellen J, MacPhee SM (2001) Philosophy of environmental enrichment: past, present, and future. Zoo Biol 20:211–226. https://doi.org/10.1002/zoo.1021

New LF, Moretti DJ, Hooker SK, Costa DP, Simmons SE (2013) Using energetic models to investigate the survival and reproduction of beaked whales (family Ziphiidae). PLoS ONE 8:e68725. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0068725

Nishita M, Shirakihara M, Iwasa N, Amano M (2017) Alliance formation of Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops aduncus) off Amakusa, western Kyushu, Japan. Mamm Study 42:125–130

Ramos EA, Santoya L, Verde J, Walker Z, Castelblanco-Martínez N, Kiszka JJ, Rieucau G (2022) Lords of the rings: mud ring feeding by bottlenose dolphins in a Caribbean estuary revealed from sea, air, and space. Mar Mamm Sci 38:364–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/mms.12854

Shepherdson DJ, Mellen JD, Hutchins M (2012) Second nature: environmental enrichment for captive animals. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington

Yamamoto C, Kashiwagi N, Otsuka M, Sakai M, Tomonaga M (2019) Cooperation in bottlenose dolphins: bidirectional coordination in a rope-pulling task. PeerJ 7:e7826. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.7826

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the dolphin care team of Ocean Park for their help in obtaining the observational data. I would like to express our deepest gratitude to my colleagues Rick Kwok, Iris Tan and the research volunteers. The project was approved by the Animal Welfare, Ethics and Care Committee of Ocean Park Corporation. Ocean Park Hong Kong gained accreditation from the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA), and it is also a member of the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA). The animal welfare standards at the Park were also certified by the American Humane Association under its Humane ConservationTM.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Eötvös Loránd University. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Matrai, E. Experiments with a set of cooperative enrichment devices used by groups of Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins. BIOLOGIA FUTURA (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42977-024-00218-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42977-024-00218-2