Abstract

During the early days of the initial outbreak of the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Japan, preschools were exempt from nationwide school closures, which came into effect on March 2, 2020. In addition, Japan is unique in that it experienced preschool closures without any heavy restrictions on daily life activities, making it possible to separate the effects of preschool closures from those of other anti-COVID-19 policies such as lockdown measures. This study conducted a placebo test that revealed that the decision to close or keep preschools open was left to each facility and the municipality where they were located and was characterized by relatively high randomness. Based on these advantages, we explored the effects of children’s preschool absence during March 2020 on mothers’ psychological distress. Our results showed that preschool closures caused immediate deterioration in mothers’ psychological states, with moderate psychological distress persisting for at least 5 months.

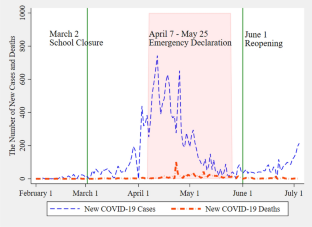

Sources: Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare “New coronavirus infection information,” URL:https://covid19.mhlw.go.jp/

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

We are willing to share our dataset and questionnaire on request.

Notes

Some studies found negative effects on mental health soon after the implementation of lockdowns (Armbruster and Klotzbücher, 2020; Sibley et al., 2020). Sibley et al. (2020) compared measurements on the Kessler (K6) Psychological Distress Scale (Kessler et al., 2002) before and after the lockdown in New Zealand and found a statistically significant increase in psychological distress.

According to (MEXT, 2020), 99.9% of elementary schools were closed as of March 10.

Following the removal of the state of emergency declaration on May 25, 2020, which lifted the obligation to close educational facilities, preschools reopened nationwide after June 2020.

For international readers, Ando et al. (2020) provides a comprehensive overview of the Japanese government’s response to the COVID-19 crisis in terms of the fiscal measures taken between January and June 2020.

We did not impose any restriction on siblings of the firstborn child in the sampling process, because restricting the sample to mothers with only one child would likely bias our results toward families with special features such as low socioeconomic status or strongly career-oriented double-income couples.

In Takaku and Yokoyama (2021), using the same survey data, we tested whether these sample drops were more likely to occur for mothers who experienced school closures in March 2020 and confirmed that there was no such trend.

Note that there were cases where preschools were closed temporarily in March, possibly due to direct or indirect exposure to COVID-19, but then reopened in April. These cases were omitted from the analysis, because even if we controlled for the potential risk, that is, the number of infected persons by prefecture, the exclusion restrictions would not have been satisfied. Moreover, given that the preschools reopened in April, the infection rate in that prefecture could not have been too high, which was another reason we could not satisfy the exclusion restrictions by controlling for only the number of infected persons by prefecture. Further, since the infection occurred in an area with a low infection rate, infections that occurred around these preschools in March could even be considered close to random. Therefore, discarding these 23 samples from our data would not hurt external validation. There were other cases in which preschools were closed in March but did not open in April. This implies that there was still a high risk of infection in April, meaning that the preschools were located in high-risk areas. Thus, in these cases, the stress caused by this situation could be controlled for by the number of infected persons per prefecture.

As stated in Sect. 3.2, the difference in K6 scores between the two groups in the previous year reflected the disparity that existed before preschool closure, and this gap was controlled for by the current control variables in the regressions.

This result may have been obtained, because traveling within the same prefecture is relatively easy, given Japan’s developed transportation network, which means that everyone in the same prefecture potentially faces the same infection risk. Thus, obtaining an insignificant coefficient from the placebo test meant that controlling for the potential risk of infection at the prefecture level would be sufficient and that there was no need to also control for a large city dummy variable.

While the true reason behind Prime Minister Abe’s declaration of school closures is not completely clear, hosting the Tokyo Olympics in August 2020 as planned would be a strong motivation to implement school closures. The official explanation in the statement from the Cabinet Office appeared to be based on the belief that infectious diseases spread rapidly among young children, as with influenza, and the government should protect children from this new disease.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. DSM IV-4th edition 1994

Ando, M., Furukawa, C., Nakata, D., Sumiya, K., et al. (2020). Fiscal responses to the COVID-19 crisis in Japan: The first six months. National Tax Journal, 73(3), 901–926.

Armbruster, S., & Klotzbücher, V. (2020). Lost in lockdown? COVID-19, social distancing, and mental health in Germany (No. 2020-04). Diskussionsbeiträge. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/218885.

Asakawa, S., & Ohtake, F. (2022). Impact of COVID-19 school closures on the cognitive and non-cognitive skills of elementary school students. Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI): Tech. rep.

Asakawa, S., Ohtake, F., & Sano, S. (2023). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the academic achievement of elementary and junior high school students: Analysis using administrative data from Amagasaki city. Tech. rep.

Baron, E. J., Goldstein, E. G., & Wallace, C. T. (2020). Suffering in silence: How COVID-19 school closures inhibit the reporting of child maltreatment. Journal of Public Economics, 190(104), 258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104258 , http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0047272720301225

Brodeur, A., Clark, A. E., Fleche, S., & Powdthavee, N. (2021). COVID-19, lockdowns and well-being: Evidence from Google Trends. Journal of Public Economics, 193(104), 346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104346 , http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0047272720302103

Cabinet Office. (2020). Prime Minister Abe’s Press Conference On February 29. https://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/98_abe/statement/2020/0229kaiken.html, accessed: 2020-09-14

Campedelli, G. M., Aziani, A., & Favarin, S. (2020). Exploring the immediate effects of COVID-19 containment policies on crime: an empirical analysis of the short-term aftermath in Los Angeles. American Journal of Criminal Justic. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-020-09578-6

Cygan-Rehm, K., Kuehnle, D., Oberfichtner, M. (2017). Bounding the causal effect of unemployment on mental health: Nonparametric evidence from four countries. Health Economics 26(12):1844–1861, https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3510, URL: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/hec.3510, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/hec.3510

Furukawa, T. A., Kawakami, N., Saitoh, M., Ono, Y., Nakane, Y., Nakamura, Y., Tachimori, H., Iwata, N., Uda, H., Nakane, H., et al. (2008). The performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the world mental health survey Japan. International journal of methods in psychiatric research, 17(3), 152–158.

Gong, J., Lu, Y., & Xie, H. (2020). The average and distributional effects of teenage adversity on long-term health. Journal of Health Economics, 71(102), 288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2020.102288 , http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167629619304989

Hipp, L., Bünning, M., Munnes, S., & Sauermann, A. (2020). Problems and pitfalls of retrospective survey questions in COVID-19 studies. Survey Research Methods, 14(2), 109–114. https://doi.org/10.18148/srm/2020.v14i2.7741

Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S. L. T., Walters, E. E., & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32, 959–976.

Leslie, E., & Wilson, R. (2020). Sheltering in place and domestic violence: Evidence from calls for service during COVID-19. Journal of Public Economics, 189(104), 241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104241 , http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0047272720301055

MEXT. (2020). What is the mext and Japanese government doing in response to COVID-19? https://www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/coronavirus/index.html. Accessed 14 Sep 2020.

Mohler, G., Bertozzi, A. L., Carter, J., Short, M. B., Sledge, D., Tita, G. E., Uchida, C. D., & Brantingham, P. J. (2020). Impact of social distancing during COVID-19 pandemic on crime in Los Angeles and Indianapolis. Journal of Criminal Justice, 68(101), 692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2020.101692. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0047235220301860.

New York Times. (2020). Japan shocks parents by moving to close all schools over Coronavirus. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/27/world/asia/japan-schools-coronavirus.html. Accessed 14 Sep 2020.

Nikkei Inc. (2020). More daycare centers are now closed [in Japanese, hoikuen hirogaru kyuen/riyoujishuku]. https://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXMZO57894650Z00C20A4CC1000/. Accessed 23 Sep 2020.

North, A. (2023). The unexpected pitfalls of work-from-home parenthood. https://www.vox.com/even-better/2023/7/31/23807375/remote-hybrid-wfh-work-parents-moms-parenting, accessed: 2024-03-28

Parker, J.J., Garfield, C.F., Simon, C.D., Bendelow, A., Heffernan, M.E., Davis, M.M., Kan, K. (2023). Teleworking, parenting stress, and the health of mothers and fathers. JAMA Network Open, 6(11), e2341,844–e2341,844. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.41844. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/articlepdf/2811325/parker_2023_ld_230205_1698176578.7112.pdf.

Payne, J.L., & Morgan, A. (2020). COVID-19 and violent crime: A comparison of recorded offence rates and dynamic forecasts (ARIMA) for March 2020 in Queensland, Australia. SocArXiv g4kh7, Center for Open Science, https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/g4kh7, https://ideas.repec.org/p/osf/socarx/g4kh7.html

Pietrobelli, A., Pecoraro, L., Ferruzzi, A., Heo, M., Faith, M., Zoller, T., Antoniazzi, F., Piacentini, G., Fearnbach, S,N., & Heymsfield, S.B. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on lifestyle behaviors in children with obesity living in Verona, Italy: A longitudinal study. Obesity, 28(8):1382–1385. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22861. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/oby.22861, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/oby.22861.

Piquero, A. R., Jordan, Riddell SANC., Bishopp, Rand, Reid, J. A., & Piquero, N. L. (2020). Staying home, staying safe? a short-term analysis of COVID-19 on dallas domestic violence. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 601–635.

Rieth, M., & Hagemann, V. (2021). The impact of telework and closure of educational and childcare facilities on working people during COVID-19. Zeitschrift für Arbeits- und Organisationspsychologie, 65(4), 202–214. https://doi.org/10.1026/0932-4089/a000370

Sakurai, K., Nishi, A., Kondo, K., Yanagida, K., & Kawakami, N. (2011). Screening performance of K6/K10 and other screening instruments for mood and anxiety disorders in Japan. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 65(5), 434–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2011.02236.x. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2011.02236.x

Sanga, S., McCrary, J. (2020). The impact of the coronavirus lockdown on domestic violence. Working paper

Sibley, C. G., Greaves, L. M., Satherley, N., Wilson, M. S., Overall, N. C., Lee, C. H. J., Milojev, P., Bulbulia, J., Osborne, D., Milfont, T. L., Houkamau, C. A., Duck, I. M., Vickers-Jones, R., & Barlow, F. K. (2020). Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and nationwide lockdown on trust, attitudes toward government, and well-being. American Psychologist, 75(5), 618–630. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000662.

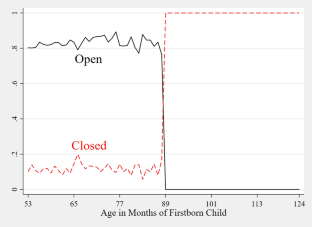

Takaku, R., Yokoyama, I. (2021). What the COVID-19 school closure left in its wake: Evidence from a regression discontinuity analysis in Japan. Journal of Public Economics, 195, 104364.

UNESCO (2020) COVID-19 response. https://en.unesco.org/covid19. Accessed 14 Sep 2020

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This research was supported by the Hitotsubashi Institute for Advanced Study and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (18K12793, PI: Izumi Yokoyama). All errors are our own.

Appendices

Appendix

School closures in other countries

This section summarizes school closures in multiple countries. In Japan, all elementary schools closed on March 2, but this requirement was waived for preschools. In contrast, as shown in Table 5, many developed countries closed schools only gradually, unlike Japan.

For example, in the UK, school closures started on February 20 in some regions, and nationwide closures were implemented approximately one month later. However, nationwide closures were abruptly implemented in Japan despite the fact that only three COVID-19 deaths had occurred by the day of the announcement.Footnote 12

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Yokoyama, I., Takaku, R. How serious was it? The impact of preschool closure on mothers’ psychological distress: evidence from the first COVID-19 outbreak. JER (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42973-024-00155-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42973-024-00155-8