Abstract

Purpose

With the exponential spread of the COVID-19 pandemic worldwide, regulatory authorities are taking measures to avoid shortages of medical devices, particularly personal protective equipment (PPE) and medical equipment. The Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (ANVISA), specifically the Medical Devices General Office (GGTPS), has been reviewing regulatory guidelines and procedures and simplifying approvals for medical devices.

Methods

Using public records, we present the Brazilian health regulatory scenario during the first four months of the pandemic (between December 31, 2019, and April 30, 2020).

Results

The ANVISA-GGTPS has been making efforts to increase the availability of medical devices for use by healthcare professionals and patients. It has simplified the rigorous regulatory system, as rising COVID-19 cases lead to a shortage of the availability of them.

Conclusion

The challenges to overcome shortages raises a pertinent question about how governments, with their respective regulatory authorities, productive supply chains, and Industry 4.0 components, will guarantee the availability of medical goods and maintain the fast flow of the goods in a flexible way, while meeting the standards of quality, safety, and effectiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

On December 31, 2019, a pneumonia-like illness of unknown etiology was reported in Wuhan, China (World Health Organization 2020a), which was later categorized as a disease caused by a virus called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The World Health Organization (WHO) later announced the official name of the disease as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) (World Health Organization 2020b).

COVID-19 is transmitted through contact with an infected person’s respiratory droplets or via aerosol (Holland 2020). The estimated incubation period, after exposure to the virus, is between 2 and 14 days, as announced by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2020). Most COVID-19 victims who succumbed are older adults, followed by patients with co-morbidities such as chronic lung disease, serious heart conditions, diabetes, and cancer (Kimball 2020; Mehra 2020). A fatality rate of 20% has been estimated for patients above the age of 80 (Haines 2020). Nearly one and a half years after the COVID-19 was declared a pandemic, the total number of confirmed cases was more than 180 million, and an estimated 3.9 million deaths have been reported worldwide (Roser 2020).

Respiratory etiquette, that is, practicing hand hygiene using an alcohol-based hand sanitizer, covering mouth with a flexed elbow while coughing or sneezing, and practicing social distancing (Holland 2020), can prevent the transmission of COVID-19. Almost 80% of the infected people tend to suffer a mild respiratory disease or remain asymptomatic and can be treated at home (Emanuel 2020; Gandhi 2020). However, those with severe respiratory symptoms require hospitalization, thus placing immense pressure on the availability of medical equipment as well as beds in the intensive care unit (ICU). It is estimated that each COVID-19 infected person spreads the virus to two others (Emanuel 2020; Li 2020). The exponential increase in the number of infected people (McMichael 2020) has increased the demand for medical devices in hospitals. Additionally, medical personal protective equipment (PPE) kits are in high demand, especially from healthcare workers.

The Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (ANVISA) is an autarchy associated with the Ministry of Health, part of the National Health Surveillance System (SNVS), functioning across the country. The ANVISA’s Medical Devices General Office (GGTPS) is the regulatory authority responsible for approving the sale of medical devices in the open market. Medical devices are categorized into four types: (i) medical equipment, (ii) materials for health use, (iii) orthopedic implants, and (iv) in vitro diagnostic medical test kits. These devices include implants; diagnostic tests; ventilators; and PPE components such as masks, face shields, respirators, surgical gowns, and gloves.

Broadly, to ensure safe and effective implementation for patients and healthcare professionals, medical devices must comply with stringent health legislations regarding design, manufacture, and quality control, among others. In addition, to meet various technical requirements, PPE must be approved based on the labor laws Regulatory Standards (NR6) released by the Brazilian Secretary of Labor.

Attributable to the increased demand for medical devices during treatment and protection, as well as shortages of products in the market, ANVISA has been amending regulatory requirements to meet Brazil’s growing demand for resources during the pandemic. The dominant focus of this study is to present to the international community the simplification of guidelines for regulatory practices (fast track approval for market) related to medical devices in Brazil, current initiatives for developing new technologies in manufacturing, and the emerging scenario.

Material and methods

First, we collected available information related to the COVID-19 pandemic from a global perspective, from December 31, 2019. We then obtained documents focusing on medical devices, regulatory decisions, technical notes, guidance material, and data from official Brazilian government press releases, including the Ministry of Health and ANVISA. Information regarding number of confirmed cases, deaths, daily new cases (published online at https://covid.saude.gov.br/), and regulatory requirement documents reported in Brazil were also collected. The collected data were analyzed and plotted in a graphical profile, describing the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths versus information published regarding simplification of the regulatory practices, relating them to the general overview of the Brazilian health system. Subsequently, we compared the regulatory requirements for medical device approvals before December 31, 2019, and during the pandemic period. The databases were accessed between December 31, 2019, and April 30, 2020. Finally, the worldwide status of medical device regulations during the COVID-19 scenario is discussed.

Results

Table 1 depicts a chronological summary of the main events related to COVID-19, published by the WHO and the Brazilian Ministry of Health, and further action taken on medical devices regulatory releases by ANVISA from December 31, 2019, to April 30, 2020. The first COVID-19 case in Brazil was confirmed on February 26, 2020 (Ministério da Saúde 2020a), and since then, ANVISA has published some new regulations to guarantee the availability of diagnostic kits, medical equipment for patient treatment, and PPE kits for protecting health professionals.

Brazil has an insightful and rigorous medical device product approval system that complies with international guidelines such as those defined by members of the International Medical Device Regulators Forum (IMDRF members: Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Europe, Japan, Russia, Singapore, South Korea, and the USA). However, the WHO’s announcement of the COVID-19 pandemic, followed by the growing fatalities in European countries such as Spain and Italy, resulted in efforts to increase the number of ICU beds, medical equipment, PPE, and healthcare staff, among others. Owing to shortages in the supply of critical medical devices worldwide, regulatory flexibility to approve health materials during a public health calamity was required. Five important simplification releases related to medical devices have been published.

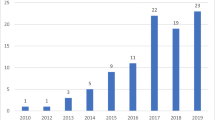

Figure 1 shows the temporal relationship between the evolution of pandemic data in the early stages and the main regulatory simplification practices published in Brazil. After Brazil’s first COVID-19 case was confirmed on February 26, 2020, ANVISA published the first regulatory amendment on March 13, 2020. The first three regulatory simplifications were published by ANVISA before 5,000 cases were confirmed. On April 30, 2020, ANVISA published the fifth important regulatory flexibility, when the number of confirmed cases in Brazil rose to approximately 85,000.

The first release related to medical devices approval was published on March 13, 2020 (Resolution of the Collegiate Board—RDC 346/2020) (Diário Oficial da União 2020b). For some products, prior to approval (high-risk classes III and IV), it is mandatory for the manufacturer to possess the required good manufacturing practices (GMP) certification. After conducting the required inspection, ANVISA certifies products with satisfactory results, both in Brazil and industrial plants overseas. Technically, the same regulatory requirements are adopted, regardless of the location. During the pandemic, ANVISA sought to offer an alternative GMP inspection process through remote inspection mechanisms (e.g., video-conferencing), or based on reports from foreign regulatory authorities: (i) PIC/S (Pharmaceutical Inspection Cooperation Scheme) for certifications related to drugs and pharmaceutical supplies; (ii) MDSAP (Medical Device Single Audit Program) for certifications related to health products; and (iii) program to rationalize international GMP inspections of active pharmaceutical ingredients or substances manufacturers for certifications related to pharmaceutical supplies. However, this simplification in GMP inspection was applicable to only manufacturers whose certification was not rejected in the last inspection cycle, and GMP petitions filed before the date of publication of the release. There were exceptions for temporary GMP certification; specifically local companies engaged in manufacturing products intended for control, diagnosis, prevention, and treatment, to meet health needs caused by the SARS-CoV-2, or for the availability of essential life-sustaining products threatened by shortages (imminent or in effect).

The second document published on March 20, 2020 (RDC 349/2020) (Diário Oficial da União 2020g) aimed to establish extraordinary criteria and procedures for handling requests for approval of PPE and medical devices, such as pulmonary ventilators, identified as strategic by ANVISA due to the pandemic. The various regulatory requirements established that products should be approved under the current legislation. In the absence of GMP certification issued by ANVISA, exceptional certifications obtained under the MDSAP or ISO 13485 Quality Management System were accepted. Products covered by this resolution were excluded from the mandatory certification tests to approve medical devices.

On March 21, 2020, a technical note (Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária 2020a) was published, recommending that healthcare professionals use N95 particulate respirators or equivalent for a longer period than that indicated by the manufacturers, provided the respirator is intact, clean, and dry. The regulatory authority did not recommend the use of an expired respirator. However, this recommendation was necessary during periods of extreme shortage to optimize the supply of particulate respirators, which are usually labeled as single-use medical devices. Shortly thereafter, on March 23, 2020, a regulatory simplification was published (RDC 356/2020) (Diário Oficial da União 2020h) that allowed significant changes in requirements for the manufacture, import, and purchase of PPE, medical equipment, and other medical devices that were identified as strategic by ANVISA. This resolution also allowed import of new and “not approved” products by ANVISA, such as PPE, pulmonary ventilators, circuits, connectors, respiratory valves, multi-parameter patient monitors, and other medical devices, when they are not available in the country; this was done as the products are approved in other IMDRF members countries by both public and private organizations and health services. The standard also authorizes the receipt of these items as donations, even if they are not approved by IMDRF countries. In these cases, the person in charge of imports must request prior authorization from ANVISA.

On March 31, 2020, ANVISA also released a technical note (Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária 2020b) to clarify details on a policy related to the import and approval of parts and accessories of medical equipment and diagnostics, due to the dynamism of the import processes. On April 15, 2020, it published a basic and simplified step-by-step guide for developing a pulmonary ventilator, with the applicable technical standards and regulatory references. Subsequently, on April 20, 2020, ANVISA published a resolution (RDC 375/2020) (Diário Oficial da União 2020j) that simplified the procedure for conducting clinical trials of high-risk class products (changed from Investigational Medical Device Dossier (IMDD) for the notification regime). Clinical trials involving these products can be submitted in a clinical research notification form, defined as in the document RDC 10/2015, indicating that these products do not have to wait for prior approval, making the procedure similar to the low-risk class I and II products. Before the pandemic, risk class III and IV products had to go through prior agency analysis by sending the IMDD. Finally, on April 30, 2020, ANVISA authorized (RDC 378/2020) (Diário Oficial da União 2020k) the import of used medical equipment, previously approved as pulmonary ventilators, vital sign monitors, and infusion pumps, for exclusive ICU applications.

Figure 2 summarizes the workflow for medical devices approval in Brazil before (Fig. 2a) and during the COVID-19 pandemic (Fig. 2b). This workflow shows the main activities in industrial plant facilities starting from inspection to final approval by ANVISA. Figure 2b highlights the workflow for medical devices intended for COVID-19 prevention, diagnosis, and treatment after simplification of regulatory practices (fast track pathways). It is clear that many steps involved in the approval of medical devices intended for the market (Fig. 2a) are no longer necessary. For instance, to manufacturing PPE in Brazil or import it from other countries, it can be observed that prior authorization was no longer required. For high-risk medical devices, such as those used in ICU, requirement of GMP certification issued by ANVISA, product certification tests, and clinical trials for products with new technologies are no longer needed for local industrial plants. Furthermore, new and used ICU products can be imported, if previously approved in IMDRF member countries.

Discussion

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, workflow approval for all medical devices included inspection of the company’s facilities, such as industrial plants, certification of design controls, manufacturing procedures, and quality systems, in addition to product validation and mandatory tests. Implementing the requirements mandated in this complex workflow was often slow and expensive. Most regulatory health agencies, regardless of country, routinely classify medical products by risk classes, with a higher number corresponding to a medical product which, in the event of a failure, may cause greater damage to users or patients.

A thorough analysis process for approval of a medical product is needed to guarantee efficacy and safety for patients and users and to ensure that the medical device perfectly meets the purposes for which it has been designed. Thus, rigor in inspections, documents, tests, and proof of effectiveness and safety studies, which must be submitted for approval, is directly linked to the risk classification of a product. The GGTPS of Brazil is responsible for receiving the documentation from companies and providing approval for introducing medical devices in the market. However, before medical devices receive marketing approval, there are several steps that involve inspection and approval at the municipality, state, and federal levels. On-site inspection of industrial plants aims to provide approval for the company’s facilities by municipality and state authorities (architectural project, fire brigade, environment, and sanitation departments). The company’s facilities must also be approved by ANVISA’s directory, Companies Permits Coordination (COAFE), which is responsible for publishing the operational authorization based on reports issued by the SNVS authorities.

Next, companies need GMP certification, which is overly complex and involves the establishment of various specifications for design, manufacture, packaging, labeling, storage, installation, and servicing of devices intended for human use. Finally, medical devices are subjected to validation tests. Some of them need mandatory certification issued by the National Institute of Metrology (INMETRO), whereas others with new technologies must undergo clinical trials.

The COVID-19 pandemic has presented numerous challenges to the Brazilian regulatory authority, which has continually simplified various regulatory practices for medical product approval, as the growing number of deaths and confirmed COVID-19 cases have reduced the availability of medical equipment and PPE.

Figure 1 clearly shows that Brazil has adopted greater flexibility with the increase in the number of people infected with COVID-19. During the first four months of the pandemic, ANVISA had published simplified procedures related to medical devices. All regulatory simplification measures undertaken owing to the emergency have an expiration date. However, it is worth examining if the effectiveness and safety of the products have been fully guaranteed.

Similarly, some health regulatory authorities, who are IMDRF members, have published regulatory simplification practices for the approval of medical devices during the COVID-19 pandemic, which are highlighted as follows. On March 18, 2020, the Minister of Health (Canada) said that Canada was accelerating import, sale, and review of medical devices, including ventilators (Government of Canada 2020). The US Food and Drug Administration (USA) determined, on March 30, 2020, that if the components of PPE kits, such as gloves, masks, and lab coats, are unavailable, they could be improvised (US Food and Drug Administration 2020). On April 1, 2020, the Health Sciences Authority (Singapore) authorized the use of anesthesia machines and positive airway pressure devices as emergency ventilators without prior approval (Health Sciences Authority 2020). On April 8, 2020, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (Australia) published minimum technical requirements for ventilator use (Therapeutic Goods Administration 2020). Other health regulatory authorities also published simplification measures during the pandemic period. For instance, on April 17, 2020, the Health and Safety Executive (UK) approved reuse of PPE (Public Health England 2020). However, such comparisons between regulatory actions taken by agencies should not be made directly, as they depend on heterogeneous factors such as number of inhabitants, population density, supply chain, and pre-existing stock of medical devices.

Health authorities of some countries relaxed the requirements for approval of medical devices due to growing demand and need. On the one hand, there were countries with a lower incidence of contamination by COVID-19 and a greater availability of ICU beds, PPE kits, healthcare professionals, and supplies; subsequently, these countries could postpone or may not have to employ regulatory flexibility for medical devices approval. On the other hand, countries with a high incidence of contamination and low availability of resources have been trying to use alternatives, for example, employing the idle productive capacity available in the maintenance and manufacture of medical devices, such as respiratory ventilators, other ICU equipment, and PPE. Brazil has been using human resources and infrastructure from universities, technical schools, research centers, and companies from different sectors for the maintenance and manufacture of PPE and medical equipment parts and accessories, especially ventilators.

During the pandemic, the responsibility of product validation rests with the clinical engineering department of the health institution or the company supplying the equipment. The approval process is more critical in manufacturing; thus, the easiest and safest way to meet the demand for medical devices could be the following: industries that received approval for medical devices from the regulatory authority should consider outsourcing parts (components) of the production process from companies in other sectors. However, in partnership with research centers and universities, innovative makers, hobbyists (Armani 2020), and several other companies worldwide have been developing alternative PPE kits and medical equipment parts through accelerated production (Longhitano 2020; Longhitano and Silva 2021b; Longhitano et al. 2021b) and at a low cost; for instance, F1 Mercedes, in partnership with engineers and clinicians at University College London, developed a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) device that is being successfully tested on COVID-19 patients undergoing treatment before invasive mechanical ventilation (Mahase 2020). Nevertheless, many of these measures can void the various warranty and technical assistance contracts and potentially become judicial actions in the future; however, the best way to deal with this situation remains to be defined.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused extensive regulatory changes in Brazil, which will likely be in force for months or even years. However, the challenges that must be overcome during this pandemic or others that can potentially occur in the future raise the question of how governments, with their respective regulatory authorities, productive supply chains, innovative makers and hobbyists, and Industry 4.0 components, will guarantee the availability of healthcare professionals, field hospitals, ICU beds, medical equipment, and PPE, in a swifter and more flexible way in the future, while still meeting all the requirements for quality, safety, and effectiveness, going beyond the purpose for which they have been designed.

References

Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA). Nota Técnica GVIMS/GGTES/ANVISA no 04/2020 [Internet]. Brasília: ANVISA; 2020a. https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/centraisdeconteudo/publicacoes/servicosdesaude/notas-tecnicas/nota-tecnica-gvims_ggtes_anvisa-04_2020-25-02-para-o-site.pdf. Accessed 23 January 2011.

Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA). Nota Técnica no 23/2020/SEI/GCPAF/GGPAF/DIRE5/ANVISA [Internet]. Brasília:ANVISA; 2020b. https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/setorregulado/regularizacao/produtos-para-saude/notas-tecnicas/nota-tecnica-gcpaf-no-23-de-2020.pdf. Accessed 05 January 2021.

Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA). Orientações Gerais Máscaras faciais de uso não profissional [Internet]. Brasília:ANVISA; 2020c. https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/assuntos/noticias-anvisa/2020/covid-19-tudo-sobre-mascaras-faciais-de-protecao/orientacoes-para-mascaras-de-uso-nao-profissional-anvisa-08-04-2020-1.pdf/view. Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA). Desenvolvimento regularização de ventiladores pulmonares – Emergência Covid-19 [Internet]. Brasília:ANVISA; 2020d. https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/arquivos-noticias-anvisa/501json-file-1. Accessed 15 2021.

Armani AM, Scholtz A. Low-tech solutions for the COVID-19 supply chain crisis. Nat Rev Mater [internet]. 2020;5:403–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41578-020-0205-1.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Symptoms of Coronavirus [Internet]. Georgia: CDC; 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html. Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Diário Oficial da União (DOU). Decreto No 10.211, De 30 de Janeiro de 2020 [Internet]. Brasília: DOU; 2020a. http://www.in.gov.br/web/dou/-/decreto-n-10.211-de-30-de-janeiro-de-2020-240646239?inheritRedirect=true&redirect=%2Fweb%2Fguest%2Fsearch%3Fsecao%3Ddou1%26data%3D31–01–2020%26qSearch%3D. Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Diário Oficial da União (DOU). Resolução de diretoria colegiada – RDC no 346, de 12 de março de 2020 [Internet]. Brasília: DOU; 2020b. https://www.in.gov.br/web/dou/-/resolucao-de-diretoria-colegiada-rdc-n-346-de-12-de-marco-de-2020-247801951. Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Diário Oficial da União (DOU). Resolução de RDC no 348, de 17 de março de 2020 [Internet]. Brasília: DOU; 2020c. http://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/resolucao-rdc-n-348-de-17-de-marco-de-2020-248564332. Accessed 15 January 2021.

Diário Oficial da União (DOU). Resolução-Re no 777, de 18 de março de 2020 [Internet]. Brasília: DOU; 2020d. https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/resolucao-re-n-777-de-18-de-marco-de-2020-248808760. Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Diário Oficial da União (DOU). Decreto Legislativo no 6, de 2020 [Internet]. Brasília: DOU; 2020e. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/portaria/DLG6-2020.htm. Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Diário Oficial da União (DOU). Resolução-RDC no 350, de 19 de março de 2020 [Internet]. Brasília: DOU; 2020f. https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/resolucao-rdc-n-350-de-19-de-marco-de-2020-249028045. Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Diário Oficial da União (DOU). Resolução-RDC no 349, de 19 de março de 2020 [Internet]. Brasília: DOU; 2020g. https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/resolucao-rdc-n-349-de-19-de-marco-de-2020-249028270. Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Diário Oficial da União (DOU). Resolução-RDC no 356, de 23 de março de 2020 [Internet]. Brasília: DOU; 2020h. https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/resolucao-rdc-n-356-de-23-de-marco-de-2020-249317437. Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Diário Oficial da União (DOU). Resolução-Re no 922, de 27 de março de 2020 [Internet]. Brasília: DOU; 2020i. https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/resolucao-re-n-922-de-27-de-marco-de-2020-250059740. Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Diário Oficial da União (DOU). Resolução-RDC no 375, de 17 de abril de 2020 [Internet]. Brasília: DOU; 2020j. https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/resolucao-rdc-n-375-de-17-de-abril-de-2020-253004636. Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Diário Oficial da União (DOU). Resolução - RDC no 378, de 28 de abril de 2020 [Internet]. Brasília: DOU; 2020k. https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/resolucao-rdc-n-378-de-28-de-abril-de-2020-254764715. Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, Thome B, Parker M, Glickman A, et al. Fair Allocation of Scarce Medical Resources in the Time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2049–55. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsb2005114.

Gandhi RT, Lynch JB, del Rio C. Mild or Moderate Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1757–66. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp2009249.

Government of Canada. Ventilators for patients with COVID-19 [Internet]. Ottawa; 2020. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/covid19-industry/medical-devices/ventilator-access.html. Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Governo do Estado de São Paulo. Decreto no 64.881, de 22 de março de 2020 [Internet]. São Paulo; 2020. https://www.al.sp.gov.br/norma/193361.

Haines A, de Barros EF, Berlin A, Heymann DL, Harris MJ. National UK programme of community health workers for COVID-19 response. Lancet. 2020;6736(20):1173–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30735-2.

Health Sciences Authority (HSA). HSA’s regulatory position on respiratory devices: supply for management of COVID-19 patients [Internet]. HSA: Singapore; 2020. https://www.hsa.gov.sg/announcements/regulatory-updates/hsa-regulatory-position-on-respiratory-devices-supply-for-management-of-covid-19-patients. Accessed on January 15, 2021.

Holland M, Zaloga DJ, Friderici CS. COVID-19 personal protective equipment (PPE) for the emergency physician. Vis J Emerg Med. 2020;19:3–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.visj.2020.100740.

Kimball A, Hatfield KM, Arons M, James A, Taylor J, Spicer K, et al. Asymptomatic and presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infections in Residents of a LongTerm Care Skilled Nursing Facility —. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(13):377–81.

Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1199–207. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2001316.

Longhitano GA, Silva JV. COVID-19 and the worldwide actions to mitigate its effects using 3D printing. J 3D Print Med. 2021a;5(1):1–3. https://doi.org/10.2217/3dp-2021-0004.

Longhitano GA, Candido G, Machado LMR, Inforçatti Neto P, Oliveira MF, Noritomi PY, et al. 3D-printed valves to assist noninvasive ventilation procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic: a case study. J 3D Print Med. 2020;4(4):193–202. https://doi.org/10.2217/3dp-2020-0017.

Longhitano GA, Nunes GB, Candido G, Silva JVL. The role of 3D printing during COVID-19 pandemic: a review. Prog Addit Manuf. 2021;6:19–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40964-020-00159-x.

Mahase E. Covid-19: Mercedes F1 to provide breathing aid as alternative to ventilator. Bmj [internet]. 2020;1294(March):m1294. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1294.

McMichael TM, Currie DW, Clark S, Pogosjans S, Kay M, Schwartz NG, et al. Epidemiology of Covid-19 in a long-term care facility in King County, Washington. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2005–11. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2005412.

Mehra MR, Desai SS, Kuy SR, Henry TD, Patel AN. Cardiovascular disease, Drug Therapy, and Mortality in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e102. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2007621.

Ministério da Saúde (MS). Brasil confirma primeiro caso da doença [Internet]. Brasília: MS; 2020a. https://www.gov.br/pt-br/noticias/saude-e-vigilancia-sanitaria/2020/02/brasil-confirma-primeiro-caso-do-novo-coronavirus. Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Ministério da Saúde (MS). Novo coronavírus: 9 casos suspeitos no Brasil [Internet]. Brasília: MS; 2020b. https://antigo.saude.gov.br/noticias/agencia-saude/46300-novo-coronavirus-9-casos-suspeitos-no-brasil. Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Public Health England (PHE). Considerations for acute personal protective equipment (PPE) shortages [Internet]. PHE: London; 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-infection-prevention-and-control/managing-shortages-in-personal-protective-equipment-ppe. Accessed 01 Dec 2020.

Roser M, Ritchie H, Ortiz-Ospina E, Hasell J. Coronavirus pandemic (COVID19) [Internet]. Published online at OurWorldInData.org; 2020. http://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus. Accessed on May 27, 2021.

Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). Therapeutic goods (medical devices—ventilators) (COVID-19 emergency) exemption 2020 [Internet]. TGA: Australia; 2020. https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2020N00046. Accessed 01 Dec 2020.

U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA). Enforcement policy for gowns, other apparel, and gloves during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Public Health Emergency [Internet]. Washington: FDA; 2020. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/enforcement-policy-gowns-other-apparel-and-gloves-during-coronavirus-disease-covid-19-public-health. Accessed 01 Dec 2020.

World Health Organization (WHO). Pneumonia of unknown cause – China [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2020a. http://www.who.int/csr/don/05-january-2020-pneumonia-of-unkown-cause-china/en/. Accessed 01 Dec 2020.

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Director-General’s remarks at the media briefing on 2019-nCoV on 11 February 2020 [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2020b. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-sremarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-2019-ncov-on-11-february-2020. Accessed on December 01, 2020.

World Health Organization (WHO). Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2020c. https://www.who.int/news/item/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov). Accessed 01 Dec 2020.

World Health Organization (WHO). Rolling updates on coronavirus disease (COVID-19) [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2020d. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-%ADcoronavirus-%AD2019/events-%ADas-%ADthey-%ADhappen. Accessed on December 01, 2020.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), and the Coordinator of Superior Level Staff Improvement – Brazil (CAPES).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gabriel, L., Lopes, É. Simplification of regulatory practices for approving personal protective equipment and medical devices during the early stages of COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. Res. Biomed. Eng. 37, 765–772 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42600-021-00183-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42600-021-00183-y