Abstract

In an extraordinarily willing and swift fashion, the top leader of Shanxi Province in China, Tao Lujia [陶鲁笳, (1917–2011)], gave permission to the Red Flag Canal Project in 1960. Why was he so willing and swift to greenlight a project that would divert water from his home province to benefit the people in a neighbor province? We explored this question through a bipartite investigation. First, we dug into the empirical literature, the literature based on experience and/or observation, in search of his motivations for the action. Second, for a more systematic, deeper understanding, we examined the instance via a lens of compassion practice, an eclectic collection of theoretical constructs on compassion practice through which one can examine an individual’s behavior and performance for new insights. This article reports the second part of our research. It is a sequel to Why was Tao Lujia so willing and swift to greenlight the Red Flag Canal Project in 1960? The instance and his motivations which reports the first part of our research and is also published in this journal. Both articles are part of the SEPR mini-series on the Red Flag Canal, one of the best kept secrets in the world history of socio-ecological practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Questions for new insights

Why was Tao Lujia so willing and swift to greenlight the Red Flag Canal Project in 1960? In search for answers to this overarching question, in the first part of our research, we performed an empirical literature analysis, and raised three questions which we believe could prompt new lines of inquiry for more systematic, deeper understanding (Chen and Xiang 2020). This article reports the second part of our research which was inspired by these questions. For the sake of comprehensibility, we recommend that our readers read Chen and Xiang (2020) first to acquaint themselves with the context in which these questions were raised.

The three questions we raised point directly to an undisclosed mental-behavioral process (i.e., thinking-acting process) Tao Lujia would have gone through that impelled him to proceed toward the greenlight decision in an extraordinarily willing and swift fashion.

What personal mental-behavioral process would Tao Lujia have gone through from the mid-1940s to 1960 that enabled him, a person with many high-level leadership responsibilities, to first develop a specific desire of helping the people in a particular locale, then to keep it alive and strong for a long period of time, and eventually to fulfill it when time was ripe in 1960?

What kind of leadership role did Tao Lujia choose to play that helped impel him to go through such a lasting mental-behavioral process and allowed him to benefit from serving others?

How come he exercised this kind of leadership so well?

Answers to these questions are certainly not readily visible to the naked eye; but, as we shall show in the next two sections, they can be found with the assistance of a lens of compassion practice.

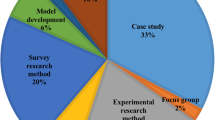

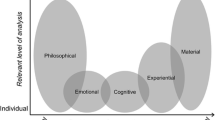

2 A lens of compassion practice

A lens of compassion practice is an eclectic collection of theoretical constructs pertaining to compassion practice, through which one can examine an individual’s behavior and performance in an instance or instances of socio-ecological practice,Footnote 1 such as the 1960 greenlight example, for new insights. In our study, the constructs are culled from a wide yet selective array of multicultural, multidisciplinary sources in philosophy, religion, history, political science, city planning, positive psychology, and neuroscience. They are mingled under five thematical categories and presented below.

2.1 Compassion and compassion practice

Compassion is an affective and motivational thought of a human being about the well-being of other human beings or even all sentient beings (Nussbaum 1996, p. 28, 2003, p. 14; Stellar et al. 2017, p. 201; The Dalai Lama 1999, pp. 123–124, 2009, p. 114). It comprises a dual mental state: a sympathetic emotion about the suffering of another individual or group; and a concomitant desire to help assuage the suffering for the welfare of that individual or group (Bernhardt and Singer 2012, p. 3; Faulkner 2014, p. 107; Goetz et al. 2010, p. 351; Jimenez 2009, pp. 209–210; Kanov et al. 2004, p. 809; Merriam-Webster 2020; Nussbaum 1996, pp. 29–31; Strauss et al. 2016, p. 19; The Dalai Lama 1999, pp. 123–124, 2009, p. 114).Footnote 2

For anyone who practices compassion (i.e., a compassion practitioner or giver), a compassion practice is necessarily a bipartite mental-behavioral process of thinking and acting: reaching the dual mental state through meditation or contemplation; and fulfilling the desire to help through actions that aim at assuaging the suffering of the other individual or group (i.e., the compassion recipient) (Barad 2007, p. 13, pp. 22–24; Forester 2020, p. 2; Martin et al. 2015, p. 239; The Dalai Lama 1999, pp. 123–124, 2020; Wong 2009, pp. 151–152).Footnote 3 The Dalai Lama, a life-long compassion scholar-practitioner (Cutler 2009, p. 113),Footnote 4 states the essential nexus between contemplating and acting in compassion practice eloquently in a 2020 TIME magazine essay entitled Prayer is not enough (The Dalai Lama 2020; parentheses by the authors):

Ever since news emerged about the coronavirus (the COVID-19 virus) in Wuhan, I have been praying for my brothers and sisters in China and everywhere else. … But prayer is not enough. … We must also remember that nobody is free of suffering, and extend our hands to others who lack homes, resources or family to protect them. This crisis shows us that we are not separate from one another—even when we are living apart. Therefore, we all have a responsibility to exercise (i.e., practice) compassion and help.

In short, compassion practice is a mental-behavioral process in which one contemplates and acts for the well-being of others’; contrary to popular belief, it includes but goes beyond meditation.

2.2 The mutual benefit of compassion practice

Compassion practice has been proven to be mutually beneficial to both the compassion practitioner and recipient in their respective pursuits of happiness (Cutler 2009, pp. xxvii–xxix; Dahl and Davidson 2019, p. 61; Halifax 2011, p. 146; Jimenez 2009, pp. 209–210; Martin et al. 2015, p. 240; Neff 2003, p. 85, p. 96; Seppala et al. 2013, p. 422, pp. 428–429; Shonin et al. 2015, p. 1162; The Dalai Lama 1999, p. 127, 2009, pp. 126–128). This is best presented in a famous aphorism by the Dalai Lama, “If you want others to be happy practice compassion; if you want to be happy practice compassion.” (The Dalai Lama 2009, p. x)

How can such a mutual benefit be even possible, given compassion practitioner’s focus on others’ well-being, as presented above in Sect. 2.1? The secret, according to the Dalai Lama, is that one’s compassion practice (for the well-being of others’) and self-compassion practice (for the compassion practitioner’s own welfare) are in fact two distinct yet intertwined aspects of a same process.Footnote 5 “In discussing the definition of compassion, the Tibetan word Tse-wa, there is also a sense to the word of its being a state of mind that can include a wish for good things (i.e., well-being) for oneself (i.e., the compassion practitioner). In developing compassion, perhaps one could begin with the wish that oneself be free of suffering, and then take that natural feeling towards oneself and cultivate it, enhance it, and extend it out to include and embrace others.” (The Dalai lama 2009, p. 114; parentheses by the authors) As such, the more one practices compassion for others’ well-being, the more one provides self-compassion for one’s own happiness (Shonin et al. 2015, p. 1161; The Dalai Lama 1999, p. 127).

With the potential for mutual benefit, compassion is a powerful engine, an energy source, residing inside a human being both for prosocial actions of serving-others and for one’s own self-healing (Barad 2007, p. 19; Jimenez 2009, pp. 209–210; Nussbaum 1996, p. 28; Seppala et al. 2013, p. 429; Stellar et al. 2017, p. 201; The Dalai Lama 1999, p. 124); and compassion practice is a process through which one ignites the engine, draws from it energy and applies to action, and ultimately realizes the potential for mutual benefit (The Dalai Lama 2009, p. 114).

2.3 Practitioner’s suffering experience and sense of interconnectedness

The dual mental state of compassion, the sympathetic emotion and desire to help, roots in a genuine sense of interconnectedness a compassion practitioner has with the compassion recipient (Barad 2007, pp. 13–14; Goetz et al. 2010, p. 351; Halifax 2011, p. 151; Jimenez 2009, p. 209, pp. 211–212; Nussbaum 1996, p. 31; 2003, pp. 12–13; The Dalai Lama 1999, pp. 126–127; 2009, pp. 117–118; 2020). Integral to such a sense of mutual relatedness or “we-ness” (Jimenez 2009, p. 212) is practitioner’s discernment that there is no real difference between herself/himself and all others in terms of suffering and need for compassion: no sentient being is exempt from suffering, suffering is a shared human experience; everyone deserves compassion, including oneself (Arendt 1963/1990, p. 85; Jimenez 2009, p. 212; Strauss et al. 2016, p. 17; also the quotes of the Dalai Lama in Sects. 2.1 and 2.2). As such, his/her “own liberation (from suffering) is not distinct from the liberation of all beings.” (Silk 2017, p. 2; parenthesis by the authors).

Personal suffering experience is a direct source for the genuine sense of interconnectedness. It comes in two forms. One is a practitioner’s self-suffering experience that is similar to, or even in common with, the one the potential compassion recipient is experiencing (for example, hardships of water shortage, loss of loved ones, or sickness) [Arendt 1963/1990, p. 86; Bernhardt and Singer 2012, p. 1, p. 4; Jimenez 2009, pp. 212–214; The Dalai Lama cited in Barad (2007, p. 14)]. The other, relatively rare but arguably more powerful, is a practitioner’s past or present co-suffering experience together, or “in the flesh”, with the present sufferer (Arendt 1963/1990, p. 85; Frost 2014, p. 51).

2.4 Authentic compassion practice and its laser focus on swift assuagement

A genuine sense of interconnectedness through personal suffering experience, be it self-suffering or co-suffering, contributes to and benefits from an authentic compassion practice, a process in which “compassion means (for the practitioner) to suffer with, to experience with or to feel with (the recipient)” (Jimenez 2009, p. 211; parentheses by the authors). Such a designation conforms with the literal meaning of compassion according to its origin—etymologically, the English word compassion is from Latin compatī, standing for “suffer with” (Barad 2007, p. 12; Collins English Dictionary 2020a).

Compassion practice of this authentic kind is a “magic”, writes German-American philosopher Hannah Arendt (1906–1975) in her 1963 book On revolution (Arendt 1963/1990, p. 81), in that it opens the heart of a practitioner to the suffering of others’, and establishes and confirms a “natural bond”—interconnectedness—between the practitioner and recipient (Ibid.) to the extent that “it is easier (for the practitioner) to suffer (herself/himself) than to see others suffer.” (Ibid., p. 86; parentheses by the authors) Without such a genuine sense of interconnectedness, argues Scottish philosopher and political economist Adam Smith (1723–1790) in his 1759 book The theory of mental sentiments with a hypothetical yet cogent example (Smith 1759/2002, pp. 157–158), a person’s compassion practice is most likely confined to a sheer vicarious, imaginative participation in the suffering of others’; and such a participation at best leads to empathy, a humane sentiment the Dalai Lama describes as compassion “at a basic level” (The Dalai Lama 1999, p. 123).

One manifestation of this magic is compassion practitioner’s laser focus on the swift assuagement of others’ suffering. In an authentic compassion practice, the practitioner perceives that the suffering of others’ “must claim for swift and direct (mitigative) action” (Arendt 1963/1990, p. 87; parenthesis by the authors). With that sense of urgency in mind, he/she is determined to do whatever is necessary and possible to help swiftly assuage the suffering of others’, and tends to put the “emotional fervor of suffering” ahead of everything else, including the often (but certainly not always) cool, rational yet politics-laden discourse (Charlebois 2017, p. 130).Footnote 6

2.5 Compassion practice is a signature trait of servant-leaders

In his 1970 seminal essay The servant as leader, American leadership scholar-practitioner Robert Greenleaf (1904–1990) coins the term servant-leader, and identifies a servant-leader as someone who believes that serving-others and self-healing are two sides of the same coin, and thus takes on the leadership role with a bona fide motivation “for his own healing” (Greenleaf 1970/2008, pp. 37–38).Footnote 7 By drawing upon exemplars of the servant-leader that range from Leo, a character in the 1932 novel Journey to the East by the Nobel laureate German-Swiss novelist Hermann Hesse (1877–1962), to Jesus, medical doctors, and ministers of different religious denominations, Robert Greenleaf reveals that one defining characteristic of servant-leaders is that of constant and continuous compassion practice. A servant-leader, he points out, “always empathizes”, strives “to bring more compassion into the lives of people (he/she serves)” (Ibid., p. 21, p. 29; parenthesis by the authors), and makes sure people’s highest-priority needs are served (Ibid., p. 15).Footnote 8

Why is compassion practice so centrally important to a servant-leader? Robert Greenleaf did not say. Nevertheless, compassion scholar-practitioners, like the Dalai Lama, can infer (not a difficult inference for them to draw) from their own practical experience. Since compassion practice is mutually beneficial to both the practitioner and recipient (see Sect. 2.2 above), for a servant-leader, serving-others with compassion arguably “constitutes the wisest course for fulfilling (enlightened) self-interest (in self-healing)” (the Dalai Lama 1999, p. 127; parentheses by the authors), so much so that the more compassionate he/she is in serving others, the happier his/her own life-work can become. Operating with this profound discernment of enlightened self-interest, servant-leaders are granted the moral authority to lead (Frick 2017).

It is noteworthy that Robert Greenleaf’s conception of servant-leader is neither foreign nor new in China. In a 2010 survey, Chinese management scholar Han Yong and colleagues found “that the concept of servant leadership holds parallel meaning in China to that of the West (primarily, that of the United States) and that the Chinese concept of servant leadership can be described precisely as public servant leadership (人民的勤务员) in the public sector and servant leadership in the non-public sector.” (Han et al. 2010, p. 265; parentheses and Chinese translation by the authors of this article). In fact, long before Robert Greenleaf’s 1970 conception, the idea to “work entirely in the people’s interests” (Mao 1944a, p. 177) had been, and still is, the motto of both the Chinese Communist Party (established in 1921) and the governments of the People’s Republic of China (established in 1949). It is written into the constitutions of the Party and the Country (e.g., the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China 2017), and most famously advocated by Chairman Mao Zedong [毛泽东, (1893–1976)], one of the founding fathers of the Party and the People’s Republic. In 1944, Chairman Mao wrote an influential essay with a telling title Serve the people (Mao 1944a), and made a powerful statement in a later speech delivered in the same year: “All of our cadres (leaders), whatever their rank, are servants of the people, and whatever we do is to serve the people.”(Mao 1944b, p. 172; parenthesis by the authors)

3 New insights via the lens

Through the lens of compassion practice above furnished, our examination of the 1960 greenlight example threw sharp light on the three questions we raised in Chen and Xiang (2020), and as such offered two fresh insights.

3.1 Insight 1: It would be a process of authentic compassion practice

In section 5 of Chen and Xiang (2020), we asked

What personal mental-behavioral process would Tao Lujia have gone through from the mid-1940s to 1960 that enabled him, a person with many high-level leadership responsibilities, to first develop a specific desire of helping the people in a particular locale, then to keep it alive and strong for a long period of time, and eventually to fulfill it when time was ripe in 1960?

The answer we found through the lens of compassion practice is, a process of authentic compassion practice as described in Sect. 2.4.

It all started with his personal co-suffering experience. During wartime in the 1940s, Tao Lujia lived and worked in Linxian. From 1945 to 1947, he was the Party Secretary of the Fifth Prefecture, a district headquartered in Linxian (Hao et al. 2011, p. 127), and the Political Commissar of the locally based division of the Eighth Route Army (八路军) (The archive 2020). It was during this 2-year period in Linxian when he gained the firsthand co-suffering experience with the Linxian people—to have endured the hardships of water shortage, experienced life-threatening draught, and felt the seriousness and intensity of the pain directly [see 4.1 in Chen and Xiang (2020)]. This, as illustrated in Fig. 1, would have set off a process of authentic compassion practice.

A systematized process of authentic compassion practice Tao Lujia would have gone through as a compassion practitioner [The compassion recipient, not shown in the figure, were the Linxian people (1) with whom he had firsthand co-suffering experience and (2) whose continuing suffering he would have vicariously participated in after left Linxian in 1947]

More specifically,

-

(1)

From the co-suffering experience between 1945 and 1947, he would have developed a deep-seated, genuine sense of interconnectedness with the Linxian people [box I in Fig. 1; see 4.1 in Chen and Xiang (2020)];

-

(2)

The co-suffering experience and the genuine sense of interconnectedness together would have enabled him to reach the dual mental state of compassion—a sympathetic emotion for the Linxian people and a strong desire to do whatever was necessary and possible to help assuage their suffering. Because of the limitations in wartime conditions, however, he was unable to take any substantive action to fulfill his desire while in Linxian. The co-suffering experience ended when he left Linxian in July 1947 (The archive 2020), but not his compassion practice. Since then, he might, or even must—judging from his swift, resolute action in 1960 and inferring from his reflective passages [see, respectively, sections 2 and 4 in Chen and Xiang (2020)]—have been able to keep up his sympathetic emotion through a vicarious participation (i.e., empathetic participation) in Linxian people’s suffering, and to sustain the desire to help (box II in Fig. 1);

-

(3)

In 1960 when the opportunity finally emerged in the form of a permission request for a grassroots water-diversion project—the Red Flag Canal Project [for the genesis of the project, see Xiang (2020a)], he wasted no time to take prosocial action upon the long-held desire of helping assuage Linxian people’s suffering. In the best of his ability as the top leader of Shanxi Province, he made bold moves beyond political limits which any provincial leader would abide by under the similar circumstance. With passionate intensity, he cut through government red tape; shun potentially protractive negotiations; gave the weighty greenlight swiftly at a single meeting; and voluntarily went the extra mile, after the greenlight decision, to make sure his subordinates do their best to help [see 2 and 4.1 in Chen and Xiang (2020)]. By so doing, he passed the finish line of a lasting process of authentic compassion practice, most likely without even knowing it himself (box III in Fig. 1).

But then, how could such a lasting authentic compassion practice from the mid-1940s to 1960 be ever possible? Besides his deep-seated sense of interconnectedness with the Linxian people and strong, sustained desire to help, there was another contributing factor—the kind of leadership he committed to exercising and learnt to exercise well.

3.2 Insight 2: He chose and learnt to be a compassionate servant-leader

We asked in our first article [section 5 in Chen and Xiang (2020)],

What kind of leadership role did Tao Lujia choose to play that helped impel him to go through such a lasting mental-behavioral process and allowed him to benefit from serving others?

How come he exercised this kind of leadership so well?

The answer we found via the lens of compassion practice? It was the servant-leadership he chose and learnt to exercise well that helped impel him to practice compassion and allowed him to benefit from serving others.

3.2.1 A hands-on apprentice in servant-leadership practice

Like most Party leaders of his time from the 1940s to the 1960s, Tao Lujia was a disciple of Chairman Mao Zedong’s; unlike most of them, however, he also considered himself an apprentice of Chairman Mao’s. During his 12-year tenure as the Party Secretary of Shanxi Province (January 1953–August 1965), he had the privilege to meet with Chairman Mao in person more than 40 times (Tao 2003, p. 3). In a 2003 book entitled Chairman Mao taught us how to be a provincial Party Secretary (Tao 2003), he acknowledges how much he learnt from these invaluable in-person experiences; and recalls how Chairman Mao, both as a role model and a master of servant-leadership, inspired and taught him to be a servant of the people and work entirely in the people’s interests (for the conception and practice of servant-leadership in China, see the third paragraph in Sect. 2.5).

In real life, he was indeed a good hands-on apprentice and put what he learnt from Chairman Mao directly into his own servant-leadership practice. Among many of his servant-leadership success examples is the Fenhe Reservoir (汾河水库) project in his home Shanxi Province. Under his strong servant-leadership, this two-year project (1958–1960) brought great socio-ecological benefits to the Shanxi people, and at the same time, boosted his own mental well-being as well [Fig. 2; see also Tao 1991; Tao 2003, pp. 118–128; Wang 2018; for a brief introduction of the Fenhe Reservoir in English, see Fan et al. (2009, p. 33)].

Source: The Shanxi Province Party History Research Institute 2013; use with permission)

Tao Lujia pulling a wheelbarrow of dirt at the Fenhe Reservoir construction site in his home Shanxi Province in 1958.

The 1960 greenlight decision for the Red Flag Canal Project, made during the Fenhe Reservoir project, is yet another example of his servant-leadership success. In this authentic compassion practice (as discussed in Sect. 3.1), Tao Lujia’s sole, laser-focused aim of taking swift prosocial action would have well been motivated by a dual intention of serving-others and self-healing. For the servant-leader Tao Lujia, to grant a much-needed greenlight to Linxian people’s do-or-die project would help himself as well—it would relieve him from a prolonged psychological burden of regret he has had about the unfulfilled desire to help the Linxian people [see 4.1 in Chen and Xiang (2020)]. To pursue this aim, he would have necessarily gone through an intertwined process of compassion practice and self-compassion practice (as described in Sect. 2.2). The subsequent boost in his mental well-being—the enduring sense of double happiness and gratitude that he enjoyed [box III in Fig. 1; 4.2 in Chen and Xiang (2020)]—exemplifies the power of compassion practice in a servant-leader’s endeavor of self-healing while serving others.

3.2.2 Inspirations from local servant-leaders in the Linxian history

“There is nothing as inspirational as a good example” (Xiang 2020b, p. 126). In exercising servant-leadership in the 1960 greenlight example, Tao Lujia might have also been inspired by local servant-leaders who voluntarily took prosocial actions in their power to assuage people’s suffering from the hardships of water shortage. Among the most noteworthy are Xie Sicong and Pi Dingjun.

In the sixteenth century during the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), the county manager Xie Sicong (谢思聪) initiated and led a locally funded project to build a 9-km-long canal in the southwest part of the county. Since its completion in 1596, the canal has been conveying spring water from the Honggushan (洪谷山) mountain to 18 nearby villages, providing drinking water to the people and domestic animals (Yang 1995, p. 461). Two hundred years later in 1785 during the Qing Dynasty (1616–1911), the local people named the canal the Duke Xie Canal (谢公渠) and built a memorial hall—the Duke Xie Temple (谢公祠), as tokens of appreciation and reverence (Ibid.).Footnote 9

Between 1943 and 1944, General Pi Dingjun (皮定均), the Commander of the locally based division of the Eighth Route Army, led his troops to build a canal for several villages in the west part of the county where they stayed (Wang and Sang 1995, pp. 13–14; Yang 1995, p. 463). This came shortly after the Linxian Battle in August 1943 in which his troops defeated the remnant Nationalist forces and Japanese puppet troops (Goodman 2000, p. xxiii, p. 54). General Pi and his troops left Linxian in September 1944 (Chinanews.com 2014). Later, the beneficiary villagers appreciatively called it the Goodwill Canal (爱民渠) [Yang 1995, p. 461] to recognize the troops’ compassionate, prosocial action through what American political scientist Tania Chacho calls “soft uses of military power” (Chacho 2009, p. 3).Footnote 10

In these two examples, Xie Sicong and Pi Dingjun exercised their compassionate servant-leadership effectively. They both had firsthand co-suffering experiences with the Linxian people; both took prosocial actions to help assuage Linxian people’s suffering from the hardships of water shortage; and their efforts were successful and acknowledged by the local beneficiaries. Might they have gone through a process of compassion practice comparable to the one Tao Lujia would have gone through (as illustrated in Fig. 1)? Was Tao Lujia aware of their prosocial actions and the lasting “goodwill benefits” the actions brought to the Linxian people (Chacho 2009, p. 3)? Was his 1960 compassionate, prosocial action inspired, even just in part, by those of Xie Sicong and Pi Dingjun? Evidence has yet to be found to answer these questions.

4 Takeaways

With the new insights in the preceding section, we wrap up our second part of research on Tao Lujia’s 1960 prosocial action in three brief subsections.

4.1 A plausible, more systematic, and deeper understanding

Why was Tao Lujia so willing and swift to greenlight the Red Flag Canal Project in 1960? About this overarching question of our research, we gained a plausible, more systematic, and deeper understanding via a lens of compassion practice. The new understanding complements what we learnt in the first part of our research [reported in Chen and Xiang (2020)], and comes in three interrelated parts.

-

(1)

The 1960 greenlight was a prosocial fruit of a lasting process of authentic compassion practice he would have been going through since the mid-1940s, and the compassion practice was an essential part of his exercise of servant-leadership;

-

(2)

his willingness and swiftness in making the greenlight decision manifested a long-held desire to help assuage Linxian people’s continuous suffering from water shortage;

-

(3)

the desire stemmed from his own co-suffering experience with the Linxian people in the mid-1940s, to fulfill it was thus not only prosocial but also self-healing.

4.2 A message to socio-ecological practitioners, especially leaders

The new understanding we gained sends a cogent, positive message to all who are engaged in socio-ecological practice, especially those who are bestowed on the leadership position—to paraphrase the Dalai Lama (2009, p. x; also quoted in the first paragraph in Sect. 2.2 of this article):

If you want yourself and the people you serve to be happy, be a servant-leader and practice compassion.

4.3 A message to socio-ecological practice researchers

In a 2019 essay entitled Ecopracticology: the study of socio-ecological practice, Chinese-American geographer and planning scholar Wei-Ning Xiang (the coauthor of this article) notes that there is a lack of leadership research in the study of socio-ecological practice—practitioners’ leadership has rarely been a topic of scholarly inquiry (Xiang 2019, p. 9). He regards this status quo as a missing link in the ecopracticological scholarship and calls for more leadership research.

The research reported in this article and in its sister piece (i.e., Chen and Xiang 2020) is an attempt, admittedly a rudimentary one, in this direction. Through a real-world example, it shows how positive and powerful a servant-leader’s compassion practice, a “soft side of leadership” in the eyes of many scholars (Brown 2005), can be in socio-ecological practice. It also demonstrates, in a rather modest way though, how fruitful the leadership research can be and how much it can potentially enrich the study of socio-ecological practice. With that, we hope that more colleagues from around the world will join us in this worthy endeavor.

Notes

Socio-ecological practice is the human action and social process that take place in specific socio-ecological context to bring about a secure, harmonious, and sustainable socio-ecological condition serving human beings’ need for survival, development, and flourishing. It includes six distinct yet intertwining classes of human action and social process—planning, design, construction, restoration, conservation, and management (Xiang 2019, p. 7).

[1] In the 2009 Encyclopedia of positive psychology, American psychologist Sherlyn Jimenez provides a useful comparison of compassion with related yet distinct constructs of altruism, compassionate love, empathy, pity, and sympathy (Jimenez 2009, pp. 210–211). In addition to an affective and motivational state, some psychologists also consider compassion to be a trait, a “general style[s] of emotional responses that persist(s) across context and time.” (Goetz et al. 2010, p. 353; parentheses by the authors of this article). [2] In a 2007 article entitled The understanding and experience of compassion: Aquinas and the Dalai Lama, American philosopher Judith Barad provides a useful comparison of compassion conceptions between Buddhism and Christianity (Barad 2007). [3] British psychologist Clara Straus and coauthor colleagues offer a comprehensive, up-to-date review of various, mostly complementary definitions of compassion in Strauss et al. (2016). [4] Like emotion, desire is also a mental state (Reisenzein 2007, p. 248).

[1] The Dalai Lama identifies yet a third stage of compassion practice at which dissipates a practitioner’s feeling that he/she is separate from all others, and as such he/she will always be fully engaged in the welfare of others (Barad 2007, p. 22). [2] A compassion practice of this kind is integral to the ideal of the bodhisattva in Mahayana Buddhism (Shonin et al. 2015, p. 1162; Silk 2017; The Dalai Lama 2009, p. 118; Wong 2009, pp. 151–152). A bodhisattva is an enlightened individual who practices compassion to save all sentient beings from suffering (Shonin et al. 2015, p. 1162; Wong 2009, p. 151) [Chinese: 慈悲为怀、普度众生的菩萨]; Guanyin (Chinese: 观音菩萨) is the most well-known and respected bodhisattva in China and across the East Asia. [3] Mahayana Buddhism (Sanskrit: “Great Vehicle”; Chinese: 大乘佛教) is influential in China since the Han dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE). Not only is it predominant in Chinese Buddhism—”[A]ll Chinese Buddhist monks are Mahayanists” (Silk 2017), but it is also one of three dominant Chinese philosophies, along with Confucianism and Daoism, that constitute the cornerstones of Chinese cultural beliefs (Palko and Xiang 2020; Wong 2009, pp. 149–152]. [4] American planning scholar John Forester regards the action leg of a compassion practice as “kindness”—“If ‘compassion’ refers to a more general concern toward Others’ welfare, ‘kindness’ is our specific action toward the Other.” (Forester 2020, p. 2). [5] Compassion practice at the organization level carries a different meaning, and is often regarded as an organizational tool to promote the well-being of employees in workplace [For a definition of compassion practice in medical care, for example, see Table 1 in McClelland et al. (2018, p. 5)].

In this article, we regard the Dalai Lama as a compassion scholar-practitioner even though we do not necessarily agree with some of his political positions. A scholar-practitioner is a scholar who is dedicated to generating new knowledge that is useful to practitioners and fellow scholars (Xiang 2019, p. 7).

Piggybacking on the compassion conception, American education psychologist Kristin Neff defines self-compassion as an emotionally positive, self-healing mental state that “could also benefit society, as it would encourage a kinder, less self-absorbed, less isolated, and more emotionally functional populace.” (Neff 2003, p. 85, p. 96) She identifies three main components of self-compassion: self-kindness, feelings of interconnectedness, and mindfulness (Ibid., p. 85, pp. 89–90).

Does this mean that, in a world where politics is ubiquitous, people who practice authentic compassion must act as impractically as Don Quixote, the hero in Miguel de Cervantes’s 1605/1615 satirical novel Don Quixote de la Mancha (Collins English Dictionary 2020b), did in striving to fulfill their desires to help assuage others’ suffering? Of course not. In a 2020 essay Our curious silence about kindness in planning: challenges of addressing vulnerability and suffering, John Forester shows, drawing on a fine-grained analysis of three real-world examples, that compassion practitioners can be practically effective if and when they make “contingent, contextually sensitive practical judgments” prudently (Forester 2020, p. 2). He provides an ensemble of four strategies for making these judgments well that involves learning, contemplation, and moral improvisation (Ibid., p. 13). Later, in an essay Beyond blame: leadership, collaboration and compassion in the time of COVID-19, he and coauthor George McKibbon stress that these strategies are among the requisites of compassion practice (Forester and McKibbon 2020).

Underling Greenleaf’s conception of servant-leader is the classic notion of heroic leadership (i.e., “the great man” theory in leadership literature) (Frick 2004, p. 339). For a succinct review of leadership theories, especially on the evolution from traditional “charismatic,” “mythic,” “heroic,” and “visionary” leadership to trending “emergent,” “distributed,” and “complexity leadership,” see McKelvey (2010, pp. 4–8).

Here we equate Greenleaf’s conception of empathy to the compassion construct by the Dalai Lama. “[E]mpathy is the imaginative projection of one’s own consciousness into another being.” (Greenleaf 1970/2008, p. 21) “At a basic level, compassion is understood mainly in terms of empathy—our ability to enter into and, to some extent, share others’ suffering.” (The Dalai Lama 1999, p. 123).

The English translation of 谢公 as Duke Xie follows the translation of 公 in Fan (2016, p. 31).

Interested readers can locate the Goodwill Canal and the Duke Xie Canal on the map in Figure 1 in Chen and Xiang (2020).

References

Arendt H (1963/1990) On revolution. Penguin Books, Harmondsworth

Barad J (2007) The understanding and experience of compassion: Aquinas and the Dalai Lama. Buddh-Christ Stud 27:11–29

Bernhardt BC, Singer T (2012) The neural basis of empathy. Ann Rev Neurosci 35:1–23

Brown PB (2005) Resonate!; Resonant leadership: renewing yourself and connecting with others through mindfulness, hope and compassion. CIO Insight 1(60):1

Chacho TM (2009) Lending a helping hand: the People’s Liberation Army and humanitarian assistance/disaster relief. US Air Force Institute for National Security Studies, USAF Academy, Colorado. https://www.usafa.edu/app/uploads/14_LENDING-A-HELPING-HAND-THE-PEOPLES-LIBERATION-ARMY-AND-HUMANITARIAN-ASSISTANCE-DISASTER-RELIEF.pdf. Accessed 29 Feb 2020

Charlebois T (2017) Coldness and compassion: the abnegation of desire in the political realm. MA thesis, the Department of Political Science, University of Victoria, Victoria

Chen Y, Xiang W-N (2020) Why was Tao Lujia so willing and swift to greenlight the Red Flag Canal Project in 1960? The instance and his reflections. Socio-Ecological Practice Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42532-020-00060-5

Chinanews.com (2014) General Pi Dingjun. [中新网(2014)虎将皮定均]. http://www.chinanews.com/mil/2014/05-06/6138027.shtml. Accessed 4 Apr 2020

Collins English Dictionary (2020a) Compassion. Collins English Dictionary. https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/compassion. Accessed 22 May 2020

Collins English Dictionary (2020b) Don Quixote. Collins English Dictionary. https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/don-quixote. Accessed 5 Aug 2020

Cutler HC (2009) Introduction to the 10th anniversary edition: the art of happiness: looing back and looking forward. In: The Dalai Lama (ed) The art of happiness, 10th anniversary edition: a handbook for living, pp. xiv–xxx. Riverhead Books, New York

Dahl J, Davidson RJ (2019) Mindfulness and the contemplative life: pathways to connection, insight, and purpose Cortland. Curr Opin Psychol 28:60–64

Fan CF (2016) Culture, institution, and development in China: the economics of national character. Routledge, New York

Fan SF, Feng MQ, Liu Z (2009) Simulation of water temperature distribution in Fenhe Reservoir. Water Sci Eng 2(2):32–42

Faulkner N (2014) Guilt, anger and compassionate helping. In: Ure M, Frost M (eds) The politics of compassion, 107–120. Routledge, London

Forester J (2020) Our curious silence about kindness in planning: challenges of addressing vulnerability and suffering. Plan Theory. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095220930766

Forester J, McKibbon G (2020) Beyond blame: leadership, collaboration and compassion in the time of COVID-19. Socio-Ecol Pract Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42532-020-00057-0

Frick DM (2004) Robert K. Greenleaf: a life of servant leadership. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, San Francisco

Frick DM (2017) Grateful leadership is servant leadership. Center for Grateful Leadership. https://gratefulleadership.com/don-m-frick-ph-d/. Accessed 1 Aug 2020

Frost L (2014) Compassion as risk. In: Ure M, Frost M (eds) The politics of compassion, 51–62. Routledge, London

Goetz JL, Keltner D, Simon-Thomas E (2010) Compassion: an evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychol Bull 136(3):351–374

Goodman DSG (2000) Social and political change in revolutionary China: the Taihang base area in the war of resistance to Japan, 1937–1945. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Lanham

Greenleaf RK (1970/2008) The servant as leader. The Greenleaf Center for Servant Leadership, Westfield

Halifax J (2011) The precious necessity of compassion. J Pain Symptom Manag 41(1):146–153

Han Y, Kakabadse NK, Kakabadse A (2010) Servant leadership in the People’s Republic of China: a case study of the public sector. J Manag Dev 29(3):265–281

Hao J, Yang Z, Li Y (2011) Yang Gui and the Red Flag Canal. Central Compilation and Translation Press, Beijing (in Chinese) [郝建生,杨增和,李永生 (2011)《杨贵与红旗渠》,中央编译出版社, 北京]

Jimenez S (2009) Compassion. In: Lopez SJ (ed) Encyclopedia of positive psychology. Wiley, Malden, pp 209–215

Kanov JM, Maitlis S, Worline M et al (2004) Compassion in organizational life. Am Behav Sci 47(6):808–827

Mao Z-D (1944a) Serve the people. In: Foreign Language Press (1969) (ed) Selected works of Mao Tse-Tung, III. Foreign Language Press, Beijing, pp 177–178

Mao Z-D (1944b) The tasks for 1945 (December 15, 1944). In: Foreign Language Press (1966) (ed) Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung. Foreign Language Press, Beijing, pp 172–173

Martin D, Seppala E, Heineberg Y et al (2015) Multiple facets of compassion: the impact of social dominance orientation and economic systems justification. J Bus Ethics 129(1):237–249

McClelland LE, Gabriel AS, DePuccio MJ (2018) Compassion practices, nurse well-being, and ambulatory patient experience ratings. Med Care 56(1):4–10

McKelvey B (2010) Complexity leadership: the secret of Jack Welch’s success. Int J Complex Leadersh Manag 1(1):4–36

Merriam-Webster (2020) Compassion. In: Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/compassion. Accessed 6 Apr 2020

Neff K (2003) Self-compassion: an alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Identity 2:85–101

Nussbaum M (1996) Compassion: the basic social emotion. Soc Philos Policy 13:27–58

Nussbaum M (2003) Compassion & terror. Dædalus 132(1):10–26

Palko HC, Xiang W-N (2020) In fighting common threats, people’s deep commitment to taking collective action matters: examples from China’s COVID-19 battle and her other combats. Socio-Ecol Pract Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42532-020-00056-1

Reisenzein R (2007) What is a definition of emotion? And are emotions mental-behavioral processes? Soc Sci Inf 46(3):424–428

Seppala E, Rossomando T, Doty JR (2013) Social connection and compassion: important predictors of health and well-being. Soc Res Int Q 80(2):411–430

Shonin E, Van Gordon W, Compare A et al (2015) Buddhist-derived loving-kindness and compassion meditation for the treatment of psychopathology: a systematic review. Mindfulness 6:1161–1180

Silk JA (2017) Mahayana. Encyclopedia Britannica, Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Mahayana. Accessed 01 July 2020

Smith A (1759/2002) The theory of mental sentiments. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Stellar JE, Gordon AM, Piff PK et al (2017) Self-transcendent emotions and their social functions: compassion, gratitude, and awe bind us to others through prosociality. Emotion Rev 9(3):200–207

Strauss C, Taylor BL, Gua J et al (2016) What is compassion and how can we measure it? A review of definition and measures. Clin Psychol Rev 47:15–27

Tao L (1991) Chairman Mao brought us golden dew of ideas: a recollection of the Fenhe Reservoir project. In: Tao L (1993) A memoir of Chairman Mao by a provincial Party Secretary, 97–107. Shanxi People’s Press, Taiyuan (in Chinese) [陶鲁笳 (1991) 毛主席给我们送来了及时雨—回忆汾河水库的建设,收录在:陶鲁笳 (1993) 《一个省委书记回忆毛主席》, 山西人民出版社,太原,第97–107页]

Tao L (2003) Chairman Mao taught us how to be a provincial Party Secretary. Central Party Literature Press, Beijing (in Chinese) [陶鲁笳 (2003) 《毛主席教我们当省委书记》, 中央文献出版社,北京]

The 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (2017) Constitution of Communist Party of China, revised and adopted at the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China on October 24, 2017. Xinhua News Agency. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/special/2017-11/03/c_136725945.htm. Accessed 1 April 2020

The Archive (2020) Tao Lujia. Jinsuiw.com. http://www.jinsuiw.com/index.php?p=news_show&lanmu=28&c_id=71&id=583 (accessed March 30, 2020) (in Chinese) [资料室(2020)《陶鲁笳》,晋绥网]

The Dalai Lama (1999) Ethics for the new millennium. Riverhead Books, New York

The Dalai Lama (2009) The art of happiness, 10th anniversary edition: a handbook for living. Riverhead Books, New York

The Dalai Lama (2020) “Prayer is not enough.” The Dalai Lama on why we need to fight coronavirus with compassion. TIME, April 14, 2020 5:23 pm EDT. https://time.com/5820613/dalai-lama-coronavirus-compassion/. Accessed 22 May 2020

The Shanxi Province Party History Research Institute (2013) Selected works of Tao Lujia. Corpus of Chinese Communist Party History, Beijing [中共山西省党史办公室 (2013)《 陶鲁笳文集 》, 中共党史出版社,北京]

Wang Y (2018) Tao Lujia: Following Chairman Mao’s lead, Learning how to build socialist China (in Chinese). J Chin Communist Party Hist 2018(10):37–41 [王燕萍 (2018)陶鲁笳:跟着毛主席学搞建设,《党史文汇》, 2018 第10期 P37–41]

Wang H, Sang J (1995) A history of the Red Flag Canal (in Chinese). SDX Joint Publishing Company, Beijing [王宏民,桑继禄(1995)《红旗渠志》, 北京三联书店,北京]

Wong PTP (2009) Chinese positive psychology. In: Lopez SJ (ed) Encyclopedia of positive psychology. Wiley, Malden, pp 148–156

Xiang W-N (2019) Ecopracticology: the study of socio-ecological practice. Socio-Ecol Pract Res 1(1):7–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42532-019-00006-6

Xiang W-N (2020a) The Red Flag Canal: a socio-ecological practice miracle from serendipity, through impossibility, to reality. Socio-Ecol Pract Res 2(1):105–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42532-019-00037-z

Xiang W-N (2020b) From good practice for good practice we theorize; in small words for big circles we write. Socio-Ecol Pract Res 2(1):121–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42532-020-00040-9

Yang G (1995) A memoir of the Red Flag Canal project [杨贵(1995)《红旗渠建设的回顾》]. In: Wang H, Sang J (eds) A history of the Red Flag Canal (in Chinese). SDX Joint Publishing Company, Beijing, pp 459–478

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the following individuals who provided valuable assistance during the preparation of this article: John Forester (Cornell University, USA); Gao Wei [(高伟) South China Agriculture University, Guangzhou, China], Li Yiman [(李沂蔓) South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China]; Kristen Banaszak, Erika Boardman, and Reese Manceaux (both with the Atkins Library, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, USA); Wang Yanping [(王燕萍) Corpus of Chinese Communist Party History, Beijing]; Shen Ning [(沈宁) (Hebei University of Engineering, Handan, China)]; Wang Fuguang [(王福光) The Shanxi Province Party History Research Institute, Taiyuan, China]; Hao Jiansheng [(郝建生), Anyang Daily, Anyang, China].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Y., Xiang, WN. Why was Tao Lujia so willing and swift to greenlight the Red Flag Canal Project in 1960? New insights via a lens of compassion practice. Socio Ecol Pract Res 2, 337–346 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42532-020-00061-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42532-020-00061-4