Abstract

Nonlinear diffusion–reaction problem was investigated experimentally for the reference reaction (hydrogenation of propylene under isothermal conditions; a slab of catalyst pellet i.e., disks of large diameter/width ratio were applied). The diffusion–reaction model in the catalyst pellet with external mass-transfer resistances was solved analytically. Dependently on parameters values, two separate solutions were found: dead zone inside the pellet does not exist or it appears. In the first case, a common model is acceptable (regular model i.e., boundary value problem), in the second one, a model includes additional condition (dead zone model i.e., free boundary problem). Analysis of the solution presented indicated that either regular or “dead zone” model correctly describes the process for specific parameter values (with the only exception—multiple steady-state region—where the correct interpretation requires the combined application of the both). This result shows that the full description of the real process includes solutions of two different BVPs. Experimental research confirmed results anticipated by theory. It allowed to draw conclusions that go beyond this particular example i.e., the regular model, commonly applied in heterogeneous catalysis, does not adequately recognize dead zone problem. If “dead zone” appears, free boundary problem has to be consider, otherwise, process simulations will be incorrect. The conclusions drawn are valid also for biofilms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Diffusion and reaction problems are of great importance for chemical and process engineering problems both from theoretical and practical point of view. The equations describing the problems differ one from another mostly by reaction terms and/or by boundary conditions, but regardless the nature of the process under consideration, the conclusions are basically equivalent. There are many different, natural phenomena that can be modeled by very similar or even identical differential equations. In the process engineering field, diffusion and reaction problems appear mainly in the processes of heterogeneous catalysis and other technologies using porous structures in which reaction can occur. Other examples of great technological interest are as follow: (1) biochemical processes in which a biofilm is penetrated by oxygen; (2) various technologies used in the field of energy accumulators (carriers), e.g., development of new electrodes using porous materials, especially in the projects associated with the alternative power engineering (hydrogen power engineering). In models used for description of such processes, a nonlinear generation term of power-law form is often applied. In the problems referring to catalysis field, the model can describe an irreversible single reaction in a slab catalyst pellet. This can be treated as an example of practical application of catalysis, and it will be discussed in details below. Biochemical analogs of such approach related to mass-transfer problems can be easily found in the literature [1,2,3].

The foundations of engineering mathematics concerning diffusion and reaction processes were presented by Aris and Temkin [4,5,6]. R. Aris in his classical book described the theory of steady state both for isothermal and non-isothermal conditions, as well as for single and multiple reactions. Moreover, the author also analyzed some features of the stability of steady state and the transient behavior of diffusing and reacting systems. M.I. Temkin showed that inside the catalyst pellet, a dead zone can be formed as a result of a progress of catalytic nature of the process-in the dead zone concentration at least of one reagent is equal to zero. The analytic solution of nonlinear problem without external mass-transfer limitations and without the dead zone was presented by Mehta and Aris [7] and Aris [6] (a part of their results were later published by Magyari [8]). For bioprocesses, biotechnological dead zones, called also enzymatic inactive regions, were investigated experimentally for limitation created by oxygen diffusion into gel beads for cephalosporin C production processes [9, 10], for the process of Penicillin G enzymatic hydrolysis to 6-Aminopenicillanic acid [11] or for the process of 3-chloro-1,2-propanediol degradation by Ca-alginate immobilized Pseudomonas putida cells [12]. In the mentioned cases, Michelis-Menten kinetics were applied. Referred above models differ one to another by kinetic rate represented by generation term. This generation term depends heavily on the type of process. The mathematical analogy of described above processes is obvious, so conclusion drawn for catalysis will be correct for bioprocesses and vice versa. There are many analogies in chemical engineering field; one of the most recognizable is Reynolds analogy that relates turbulent momentum and heat transfer.

The main goal of the research is to confirm or disconfirm the hypotheses that dead zone is formed inside the catalyst pellet under favorable conditions and to show that the correct mathematical description of a process with dead zone requires application of a model with additional condition on the boundary [4, 7]. The goal is practical, results oriented, and it can make possible to develop models of systems with very active catalysts or biocatalysts. To realize it, there was a solved problem that includes two coupled points:

- 1

To find a solution of the boundary value problem (BVP) for any set of model parameters values; intentionally and consciously an analytical method was selected to avoid numerical errors (e.g., round-off, truncation, and others) and, additionally, analysis of existence and uniqueness of solutions of both models helps to remove all doubts in results interpretation.

- 2

To choose heterogeneous chemical reaction that model corresponds to the model equation and to develop an experiment that can confirm hypotheses; this point includes also other technical aspects as catalyst, operating conditions, etc.

It was realized in the following steps:

- 1

Obtaining an analytical solution of the models for a pellet with or without the dead zone; in this way, we exclude impact of round-off, truncation, and other numerical errors on model solution.

- 2

Demonstrating that both solutions of the model without dead zone (called “regular model”) and the model with dead zone (called “dead zone model”) exist for specified values of Thiele and Biot moduli only.

- 3

Determining sets of parameters where each model is valid for a separate operating region.

- 4

Designing and performing an experiment; a range of operating conditions should ensure unambiguous interpretation of results—since the solutions are complementary, it is possible to compare the valid solution with experimental results and, in consequence, to confirm (or disconfirm) the hypothesis formulated above.

The present paper includes extension of the above mentioned works and experimental verification of conclusions. The idea of the extension consist in considering non-negligible mass-transfer resistances and lack of reagents in the pellet center. To the best of my knowledge, the problem of non-negligible mass-transfer resistances has not been presented in the literature. Since appearance of the dead zone inside a pellet (or inside biofilm) results from sufficiently large mass-transfer resistance, it would be interesting to examine role of external mass-transfer resistances in comparison with internal ones. The conception of both complementariness and antagonism of the obtained analytical solutions was confirmed by experimental results: propylene hydrogenation reaction on nickel catalyst was considered. High coincidence of experimental results and theoretical solution was observed. It allowed to draw conclusions that go beyond this particular example i.e., the regular model, commonly applied in heterogeneous catalysis, does not adequately recognize dead zone problem. If “dead zone” appears, free boundary problem has to be consider, otherwise process simulations will be incorrect, and further, the dead zone phenomenon has to be taken into account when determining operating condition for catalytic reactor. The conclusions drawn are valid also for biofilms.

There is one more, non-technical but important aspect of the present problem. The exact solutions of models considered in engineering are generally difficult to obtain, and they are rather rarely presented. Both initial and boundary value problems are usually nonlinear, and they usually have no exact analytical solutions. If analytic solution of a nonlinear problem exists, then, it is usually hard to obtain and typically it is valid in limited parameter range, e.g., for specific model parameters values. Analytical solutions of engineering models are of great importance. They allow the problem to be analyzed thoroughly, and it is also possible to find its physical features in simpler way than numerically (e.g., finding the critical (bifurcation) points and calculation of the function values in their neighborhood requires only elementary knowledge of calculus and algebra). Additionally, analytic solutions are free of round-off, truncation, and other numerical errors. To sum up, if analytical solution can be found, especially for full range of model parameters values, it is a powerful tool for the process analysis.

1.1 Theory

A steady-state diffusion process with an irreversible isothermal chemical reaction (A → R) present can be described by (in dimensionless terms)

on the assumption that power-law-type kinetic equation is valid.

If external mass-transfer resistances are not negligible, the boundary condition on the outer surface of catalyst pellet is described by

When concentration in the pellet center is greater than zero, the second boundary condition is in the form

If concentration inside the pellet reaches zero for x = xdz and 0 ≤ xdz ≤ 1, the second boundary condition is

to obtain unique solution, an additional condition should be included

For 0 ≤ x ≤ xdz concentration is equal to 0.

For the purpose of calculation simplicity, the model (1) with boundary conditions (2) and (3) will be called a regular model, while the model (1) with conditions (2), (4) and (5)—a dead zone model.

Some comments are required here. Relatively simple nonlinear governing Eq. (1) completed by most often accepted in practice BCs (Eqs. 2, 3) has solution only for Φ smaller than Φc (for n fractional and any Bim). There is contradiction between model and physical results. Values of Φ larger than Φc can be easily obtained in practice (the larger temperature the large Φ-value) and reaction effects can be observed. To remove this contradiction is necessary to replace the mentioned set of BCs by another one i.e., (2), (4) and (5). Solution of the dead zone model completes solutions of the regular one. This result shows that the full description of the real process includes solutions of two different BVPs.

2 Methods

Well-known solutions of the linear reaction–diffusion problems (n = 1 or n = 0) are omitted in the given below considerations.

2.1 Solution of Eq. (1) with boundary conditions (2) and (3)

If n ≠ − 1 Polyanin and Zaitsev [13] propose the following first integral of Eq. (1) (some symbols in the original statement have been revised to fit the notation of the present work):

The second boundary condition, Eq. (3), gives the following value of integration constant

c0 = c(0) is reagent concentration in the pellet center; the way of its determination will be presented further.

Thus Eq. (6) becomes

At the assumption that

Eq. (8) acquire the following form

The complete description of the calculation procedure, it is reasonable to consider three following cases: n > − 1, n = − 1 and n < − 1.

2.1.1 Case a (n > − 1)

When n > − 1 and u > 1, so n + 1>0 and un+1>1 and the right-hand-side terms of Eq. (10) are positive. The variables in Eq. (10) can be easily separated

Integration of this equation in the range of (0…x) and of (1…u) gives

Using the Maple© CAS-type program, the integral in Eq. (12) can be expressed in terms of Gauss hypergeometric function as follows

Combining Eqs. (12) and (13) and rearranging the result using linear transformation formulas given by Abramowitz and Stegun [14] (Chapter 15, paragraph 15.3: Linear Transformation Formulas) one can obtain

and next

Now, it is clear that hypergeometric function in Eq. (15) absolutely converges so long as − 1<n < 1 and conditionally converges when n ≥ 1 (condition of convergence ibid.).

For n ≥ 1 Eq. (15) can be transformed using linear transformation formulas to the equivalent form with absolutely convergence of hypergeometric function viz.

Using Eqs. (8) and (15) one can write the following relationships for x = 1

where cs = c(1) is reagent concentration on the pellet surface.

Combining the boundary condition (2) and Eq. (17) one can obtain

Solution of the equations set (18) and (19) gives the unknown values of c0 = c(0) and cs = c(1). The uniqueness of the obtained solutions will be discussed in the next section.

It is worth mentioning that on the basis of Eq. (10), the following formula for the effectiveness factor can be written:

2.1.2 Case b (n < − 1)

When n < − 1 and u > 1, then n + 1<0 and un+1<1 and Eq. (10) can be rearranged into

to omit complex values. Now, right-hand-side terms of Eq. (21) are positive. After separation of variables we obtain

Integration of this equation in the range of (0…x) and of (1…u) gives

In this case

It is clear that the form of integral (24) differs significantly from this given by Eq. (13).

Rewriting Eq. (24) with the use of linear transformation formulas (see case a) and combining the result with Eq. (23), we can obtain

Now, one can easily prove that hypergeometric function in Eq. (25) absolutely converges so long as n < − 1.

Applying again the same procedure as presented above, one can obtain

Solution of the equations set (27) and (28) gives the unknown values of c0 = c(0) and cs = c(1).

The effectiveness factor is given by Eq. (20).

2.1.3 Case c (n = − 1)

Finally, if n = − 1, the first integral of Eq. (1) is given by

Applying again the same procedure as given above, one can obtain

and

Solution of the equation set (32) and (33) gives the unknown values of c0 = c(0) and cs = c(1).

The effectiveness factor is given by the following equation

2.2 Solution of Eq. (1) with boundary conditions (2), (4) and additionally (5)

The first integral of Eq. (1) is given by Eq. (6)

2.2.1 Case a (n ≠ − 1)

Assuming that n ≠ − 1, and using the conditions (4) and (5) for Eq. (6) one can obtain

Thus Eq. (6) becomes

It is easy to see that the point given by the coordinate values (x = xdz, c = 0) for n < − 1 is singular, and this case will be considered separately, in the next point. If n > − 1, separation of variables gives

Integration of Eq. (36) in the range of (xdz…x) and of (0…c) holds only for n < 1 (otherwise, the right-hand-side approaches infinity at (x = xdz, c = 0). So, assuming 1 > n> − 1, we can obtain

The last equation can be easily rearranged into

Using Eqs. (36) and (38) one can write relationships for x = 1

where cs = c(1) is reagent concentration on the pellet surface.

Combining the boundary condition given by Eq. (2) with Eq. (39), it follows

Solution of the Eq. (42) gives the value of cs = c(1). Substitution cs into Eq. (41) allows the value of xdz to be obtained.

The effectiveness factor is given by

2.2.2 Case b (n = − 1)

If n = − 1, (cf. Equation 29)

The point of the coordinates (x = xdz, c = 0) is singular, and this case will be analyzed in the next point.

Thus, the solution of the dead zone problem has physical meaning for − 1<n < 1. It is consistent with the necessary conditions of the dead zone formation as presented by Andreev [15].

2.3 Singularities for n ≤ − 1

The case of n ≤ − 1 has to be considered separately.

If n < − 1, the right-hand side of Eq. (36) approaches infinity for x = xdz. To find a solution, the assumptions of Picard’s theorem for the following equation should be examined

The assumptions are satisfied; then it follows that Eq. (45) has the unique solution. The solution is identically zero (trivial solution). It is easily to show that if n < − 1, left-hand side of Eq. (36) is non-negative and its right-hand side is non-positive, so the only solution is c = 0. Analysis of Eq. (44) leads to the same conclusion. The practical aspect of the solution obtained will be discussed in next point.

2.4 Notes

-

All expressions which include hypergeometric Gauss function and imaginary error function (erfi(x)) can be easily handled using some mathematical programs as Maple, Mathematica, Matlab, etc. The procedure of finding concentration profile in the pellet (written in Maple) is available as Supplementary Material. It is noteworthy that the whole procedure (excluding auxiliary commands) includes approximately 10 instructions; the procedure writing process does not require programming skills.

-

The modern software is helpful both for finding and for analysis of a model, and it is also useful for its solving. The programs allow to handle the sophisticated analytical solutions in relatively simple way. We can easily obtain useful forms of the solutions (e.g., graphs or relationships between variables, parameters, etc.) and for this reason, it is not hard task to analyze the presented solutions.

-

For selected values of n, hypergeometric Gaussian function can be converted to algebraic or special functions. Cases n = 1 and n = 0 are presented in Results and discussion section as given below.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Uniqueness of solutions

Problem of the solution uniqueness for the presented here model without external mass-transfer resistances (Bim → ∞) was discussed earlier in details by Mehta and Aris [7]. The difference concerning the solution given in this paper consists in the fact that if negligible resistances are assumed, the value of cS = 1, otherwise cS < 1. For this reason, their argumentation is still valid, but there are some details that they are necessary to be additionally included. Let’s pay attention to the case a.

- 1.

Simple inspection of Eq. (15) shows that it is of physical meaning if c ≥ c0, where equality occurs only when the reaction rate is infinitely slow

- 2.

Eq. (18) can be rearranged to

$$\varPhi = \left( {\frac{2}{n + 1}} \right)^{{\frac{1}{2}}} \left( {c_{s}^{1 - n} - c_{s}^{ - 2n} c_{0}^{n + 1} } \right)^{{\frac{1}{2}}} \,{}_{2}F_{1} \left( {1,\frac{n}{n + 1};\frac{3}{2};1 - c_{s}^{ - n - 1} c_{0}^{n + 1} } \right)$$(46)After substitution cS = 1 Eq. (46) becomes that as previously considered by Mehta and Aris [7].

- 3.

if n ≥ 1, Φ ranges from infinity to zero as c0 ranges from 0 to cS

- 4.

if 0 ≤ n < 1, Φ decreases from finite value to zero as c0 ranges from 0 to cS

- 5.

if − 1<n < 0, Φ decreases non-monotonically from finite value to zero as c0 ranges from 0 to cS

- 6.

a relationship between c0 and cS derived from Eqs. (18) and (19) can be written in the form (see also Supplementary Material)

$$c_{0} = \exp \left\{ {\frac{{ - \ln \left( 2 \right) - 2\ln \left( \varPhi \right) + \ln \left[ {2\varPhi^{2} c_{S}^{n + 1} - {\text{Bi}}_{\text{m}}^{2} \left( {1 - c_{S} } \right)^{2} \left( {n + 1} \right)} \right]}}{n + 1}} \right\}$$(47)It shows that the relationship between c0 and cS is unique and c0 ≥ 0

- 7.

For fixed values of Φ and Bim left hand side of Eq. (19) should be larger than or equal to zero. Thus, the value of cs ≤ 1. Equality occurs only when external mass-transfer resistances are assumed to be negligible

Cases b and c can be analyzed analogously to the example given above.

3.2 Dead zone and critical value of Thiele modulus

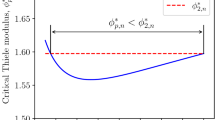

In this section, the analysis of two related problems will be presented—critical value of Thiele modulus and complementarity of regular and dead zone models.

Critical Thiele modulus Φc is the Φ-value for which concentration of reagent drops to zero at x = 0. At the assumption that c0 approaches zero, in all considered solutions, given Eqs. (15), (16) and (25), the last term of hypergeometric function approaches one; hypergeometric function converges, and it can be expressed in terms of Γ-function (Abramowitz and Stegun [14], Chapter 15 paragraph 15.1, Special Values of the Argument).

If n ≥ 1, we calculate Φc using Eq. (16) rearranged to the form

Regular model is valid for any value of Φ while the dead zone model cannot be used as it has no solutions.

If − 1<n < 1, it possible to calculate Φc using Eq. (46) (as the rearranged form of Eq. (15))

Note that Φc can be also obtained using dead zone model; for this, an assumption is needed that at the point of Φ = Φc…xdz = 0. Then Eq. (41) becomes Eq. (49) (as it was presented by Garcia-Ochoa and Romero [16]).

If − 1<n < 1, the value of Φc is finite, but it is reasonable to analyze two cases. The first one: if 0 ≤ Φ < 1, for Φ ≤ Φc the regular model have unique solutions while for Φ ≥ Φc, the unique solutions can be find from the dead zone model. In the second case if − 1 < n < 0, there is a difference. For Φc ≤ Φ ≤ Φmax exist two regular model solutions with physical meaning, one stable and one unstable. Φmax is here Thiele modulus value, for which lower and upper branch of dual solution become coincident; it is the maximum value of the right side of Eq. (46). The third solution can be obtained from dead zone model. Summarizing, in the limited range above Φc exists multiple steady-state region, in which both regular and dead zone models have solutions with physical meaning. Continuity of the solutions is achieved as it is shown below.

One can easily show the identity of the regular- and dead zone model solutions at the point of Φ = Φc. Equation (15) can be rearranged to

if c0 approaches zero, the above equation simplifies to

Calculation of c is given by Eq. (39). So, we have equality of derivatives what leads to the conclusion that regular and dead zone model are complementary.

If n < − 1, we calculate Φc using rearranged form of Eq. (25)

If n = − 1, we can calculate the value of Φc using rearranged form of Eq. (30)

As it follows from the two last equations, the value of Φc = 0, and it is a distinct difference in respect to the previously discussed case of − 1<n < 0. As a result, the region of unique solution of regular model for Φ < Φc vanishes. Moreover, the results of the dead zone model analysis (see the section Singularities for n ≤ − 1) suggest that the dead zone extends over the entire space inside the catalyst independently of Φ-value, and the reaction occurs on the pellet surface only. Concentration profiles obtained for small values of Φ confirm this interpretation (see results available as Supplementary Material). Thus, if the dead zone extends over the entire space inside the catalyst, the process can be analyzed qualitatively rather than quantitatively using dead zone model.

3.2.1 Case a (n > 1)

If n > 1, the regular model has the unique solution for any Thiele modulus value given by Eq. (15). c0 is always greater than 0, thus dead zone is not formed, Φc approaches infinity. This case was many times discussed in the literature.

3.2.2 Case b (n = 1)

If n = 1, the regular model becomes linear and it has the unique solution for any Thiele modulus value. The solution (54) was many times presented in the textbooks. Properties of the solution are the same as in case a, the dead zone is not formed.

3.2.3 Case c (0 < n<1)

If 0 < n<1, the regular model can be applied for Φ ≤ Φc; for larger Φ the dead zone model should be used. The unique solutions are given by Eq. (15) and Eq. (39), respectively. Critical value of Thiele modulus is given by (49). Typical results for different n and Bim → ∞ are presented in Fig. 1.

The shape of the presented curves is well known in the literature, but each curve consists of two parts: (1) solid line which corresponds to regular model solution for Φ ≤ Φc and (2) dashed line which corresponds to solution of dead zone model for Φ ≥ Φc. The solutions are complementary, each curve is smooth. From the figure, it is clear that: (1) the smaller n the larger η and the smaller Φc; (2) the smaller Bim the smaller η, and the smaller Φc.

The relationship between critical Thiele modulus value and external mass-transfer resistances is presented in Fig. 2. If external mass-transfer resistances increase, the value of critical Thiele modulus decreases; dependence is clearly nonlinear one.

The value of xdz coordinate characterizes a size of dead zone inside the pellet. In Fig. 3, the dependence of dead zone size on external mass-transfer resistance is presented. For Φ ≥ Φc and for any mass-transfer resistances, the value of xdz grows with increasing Φ first rapidly and then slowly.

The relationships presented in Figs. 2 and 3 are viewed also for cases d–g.

3.2.4 Case d (n = 0)

If n = 0, the regular model becomes linear and it has the unique solution for Φ ≤ Φc. The dead zone model also becomes linear, and it has the unique solution for Φ ≥ Φc. The solution (55) was many times presented in textbooks.

3.2.5 Case e (− 1<n < 0)

If − 1<n < 0, the unique solutions exist for 0 < Φ < Φc (the regular model should be used) and for Φ > Φmax (the dead zone model should be used). The results are presented in Fig. 4. For Φc ≤ Φ ≤ Φmax the multiple solutions exist. In this region, two solutions (stable and unstable) can be obtained from the regular model and one stable solution from dead zone model. Φmax is Thiele modulus value, for which lower and upper branch of dual solution become coincident. In this case, the existing opinion that for Φ > Φc the regular model is usefulness seems not be true. The smaller n the larger multiple solutions region and the zone moves toward Φ = 0. With the increase in Bim, Φc and Φmax values decrease and multiple solutions zone moves toward Φ = 0.

3.2.6 Case f (n = − 1)

Although mathematical formulas for n = − 1 and for n < − 1 significantly differ one to another, the properties of the solution are the same and will be presented below.

3.2.7 Case g (n < − 1)

If n < − 1, the multiple solutions region exist for 0 < Φ ≤ Φmax (Φc → 0). In this region, the regular model gives two solutions (stable and unstable). The results are presented in Fig. 5. Analysis of the dead zone model and asymptotic behavior of regular model show that the dead zone extends over the entire space inside the catalyst and the reaction occurs on the pellet surface only. The smaller n the narrower multiple solutions zone (Φmax decreases) and multiple steady-state region moves toward Φ = 0. If Bim increases, Φmax decreases.

In Fig. 6, all types of solutions (including n ≥ 1) obtained for simple diffusion–reaction problem are presented. The shapes of curves are the same as presented in Aris’ textbook. In multiple steady-state region, the upper branch gives the solution of dead zone model. One can easily observe that the smaller value of exponent n, the larger value of effectiveness factor for the same Φ.

The solution of the presented diffusion–reaction problem can be found for any set of values of process parameters (n, Φ, Bim) what concurs with the results of experiments presented in the literature and also with intuition. It means that the dead zone model and the regular model complement one another and both models should be considered in process modeling. Significant errors may occur if dead zone model is not taken into account.

4 Experiment

To establish correctness of considerations presented, the necessary experiments were conducted. Previously made investigations [17] show that a propene hydrogenation reaction can be described by the model discussed in the earlier sections. The experimental reaction rate corresponds to the Case c described in Sect. 3. In this case, the regular model is valid, if Thiele modulus value is smaller than its critical value, otherwise, the dead zone model is valid. Operating conditions were intentionally and consciously selected to maximize likelihood of formation of dead zone inside the pellet (the correctness of the regular model is beyond doubt, only dead zone conception and its model require experimental verification).

A short description of experiment method is presented below.

The propene hydrogenation reaction was carried out in tubular reactor (Microactivity-Efficient Unit, manufacturer: Process Integral Development Eng&Tech, Madrid, Spain) on heterogeneous nickel catalyst (type of KUB-3, manufacturer: New Chemical Syntheses Institute, Catalyst Department, Puławy, Poland). Nickel catalyst was activated in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Post-reaction mixtures were analyzed with gas chromatograph (CALIDUS™ 101 Gas Chromatograph, manufacturer: Falcon Analytical, Lewisburg, WV, USA).

The system was flushed for 30 min with a constant flow of hydrogen until a stable right temperature and pressure were obtained. Next, flow of propylene was started. Reaction was carried out for circa 1 h until the stable temperature inside the tubular reactor was reached. The relatively long time was taken to ensure that the steady-state conditions were reached. Next, the reaction mixture was analyzed.

The earlier experiment resulted in the following kinetic equation (the parameter values are rounded-off; the experimental values with confidence intervals and other details were published by Szukiewicz et al. [17]):

where rp is rate of reaction with respect to propylene, pp is partial pressure of propylene, R is gas constant, and, T is temperature.

It is easily to observe that for isothermal conditions the equation met requirements of the model under consideration.

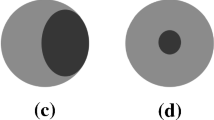

Main investigations were conducted in a slab catalyst (the single pellet). There were carried out two experiments:

- E1.

Catalyst pellet prepared as disk with diameter of 4.7 mm and thickness of 0.5 mm.

- E2.

Catalyst pellet prepared as disk with diameter of 4.9 mm and thickness of 0.35 mm.

Operating conditions are presented in Table 1.

Results obtained are presented in Table 2 and in Table 3 as well as in Fig. 7. ηexp was calculated by comparing of Thiele Φ and Weisz modulus Φw values. Mass-transfer coefficient, necessary for calculating the Biot number was taken from recommended in Perry’s handbook [18] relation (Table 5-17).

The reaction order with respect to propylene is equal to 0.5. It indicates that the concentration profile is given by Eq. (16) if dead zone inside the pellet does not exist or by Eq. (39) in the opposite case. Evaluated critical Thiele modulus value Φc ≈ 3.4 (Eq. 49) clearly indicates that for the considered case dead zone in the pellet exists. As a consequence, experimental value of effectiveness factor was compared with those obtained from Eq. (43).

The coincidence of observed results with the theoretical results was very close in both experiments. Calculated from the model effectiveness factor values varies from experimental ones more than 10% for only 5 of 40 measurements while average errors for the first and second experiment are 4% and 6%, respectively. It unambiguously confirms that conception of dead zone that arise spontaneously as a result of a fast reaction run is correct. In the region under consideration, i.e., reaction order is fractional and positive, existence and uniqueness of the presented above solutions indicate on formation of a dead zone in the pellet center despite the fact that in this area, the catalyst is active. A problem of dead zone formation is important from theoretical point of view—more difficult free boundary value problem has to be considered instead of much simpler regular boundary value problem. The problem is important also from practical point of view. Since the last columns of Tables 2 and 3 indicate the dead zone envelopes between 30 and 50% of the pellet volume, so non-productive part of the pellet is remarkable—the dead zone phenomenon has to be taken into account when determining operating condition for catalytic reactor or bioreactor.

5 Conclusions

On the basis of presented analysis the following conclusions can be drawn:

Analytical solution of the diffusion–reaction problem under consideration (single irreversible isothermal reaction with power-law-type kinetic equation) can be found for any set of process parameters (n, Φ, Bim) only if both models regular and dead zone are taken into consideration; the conclusion concurs with presented in the literature results of experiments and also with intuition.

If concentration of a reagent in the pellet center drops to zero, the modification of boundary conditions must be included; otherwise, results of modeling be falsified. This is the most important conclusion. Its practical aspect is presented below.

The dead zone and regular models complement one another and both models should be considered; solutions are smooth and continuous. Existence and complementary of the analytical solutions prove the correctness of the approach based on two models.

The solutions of the models are unique and complementary, and furthermore, they were confirmed experimentally, what follows that the dead zone presence inside a catalyst pellet or inside a biofilm requires consideration of free boundary value problem.

External mass-transfer resistances have to be generally taken into account because as it was proved in this paper, they have crucial role in the formation and position of the dead zone.

If n ≥ 1 then the regular model gives the unique solution to any Thiele modulus value.

If 0 ≤ n < 1 then the regular model can be applied for Φ ≤ Φc; for larger Φ the dead zone model should be used.

If − 1<n < 0 then the unique solution exists for 0 < Φ ≤ Φc (the regular model should be used) and for Φ > Φmax (the dead zone model should be used). For Φc ≤ Φ ≤ Φmax, the multiple solutions exist. In this region, two solutions (stable and unstable) can be obtained from the regular model and one solution (stable) from the dead zone model.

If n ≤ − 1, then the multiple solutions exist for 0 < Φ ≤ Φmax (Φc → 0). In this region, two solutions (stable and unstable) one can obtain from the regular model. In this case, the dead zone extends over the entire space inside the catalyst and the reaction occurs on the pellet surface only.

For a power-law type of kinetic equation (and for other types for which the concentration in the center of the pellet drops to zero i.e., the dead zone appears), it is necessary to use a model with modified boundary conditions (dead zone model).

The significance of the results presented here goes beyond this particular example. To the best of my knowledge, it is the only process for which analytical solution of BVP is available, and it therefore was selected to research. Irreversible, isothermal, one component reaction with power-law kinetic equation running on the slab catalyst pellet is the simplest nonlinear case. Its correct mathematical description requires application of regular model, dead zone model or both in dependence on dead zone existence i.e., a set of model parameters values. If concentration of a reagent in the pellet center drops to zero, the modification of boundary conditions must be considered (the problem becomes free boundary problem). Additionally, if irregular phenomena have to be considered for the simplest case, the same or more complex behavior will appear for more sophisticated cases. Since correctness of the conception of two complementary models that describe the problem was confirmed by experiment, the dead zone phenomenon has to be taken into account when determining operating condition for catalytic reactor or bioreactor. When significant effort is put into producing more active and more selective catalysts, formation of non-productive part of the pellet can reduce effects obtained in the laboratory. The reduction can be especially noticeable in large-scale processes.

References

Rosen G (1976) Book review. Bull Math Biol 38:95–96

Kreft JU, Picioreanu CJ, Wimpenny WT, van Loosdrecht MCM (2001) Individual-based modeling of biofilms. Microbiology 147:2897–2912

Hermanowicz SW (2001) A simple 2D biofilm model yields a variety of morphological features. Math Biosci 169:1–14

Aris R (1975) The mathematical theory of diffusion and reaction in permeable catalysts: the theory of the steady state, vol 1. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Temkin MI (1975) Diffusion effects during the reaction on the surface pores of a spherical catalyst particle. Kinet Cat 16:104–112

Temkin MI (1981) Gas diffusion in porous catalysts. Kinet Cat 22:1365–1375

Mehta BN, Aris R (1971) A note on a form of the Emden-fowler equation. J Math Anal Appl 36:611–621

Magyari E (2008) Exact analytical solution of a nonlinear reaction-diffusion model in porous catalysts. Chem Eng J 143:167–171

Araujo MLGC, Giordano RC, Hokka CO (1998) Comparison between experimental and theoretical values of effectiveness factor in cephalosporin C production process with immobilized cells. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 70:493–504

Cruz AJG, Almeida RMRG, Araujo MLGC, Giordano RC, Hokka CO (2001) The dead core model applied to beads with immobilized cells in a fed-batch cephalosporin C production bioprocess. Chem Eng Sci 56:419–425

Cascaval D, Turnea M, Galaction A-I, Blaga AC (2012) 6-Aminopenicillanic acid production in stationary basket bioreactor with packed bed of immobilized penicillin amidase—Penicillin G mass transfer and consumption rate under internal diffusion limitation. Biochem Eng J 69:113–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bej.2012.09.004

Konti A, Mamma D, Hatzinikolaou DG, Kekos D (2016) 3-Chloro-1,2-propanediol biodegradation by Ca-alginate immobilized Pseudomonas putida DSM 437 cells applying different processes: mass transfer effects. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 39:1597–1609

Polyanin AD, Zaitsev VF (1995) Handbook of exact solutions for ordinary differential equations. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Abramowitz M, Stegun IA (1972) Handbook of mathematical functions with formulas, graphs, and mathematical tables. Dover Publications, New York

Andreev VV (2013) Formation of a “dead zone” in porous structures during processes that proceeding under steadystate and unsteadystate conditions. Rev J Chem 3(3):239–269

Garcia-Ochoa F, Romero A (1988) The dead zone in a catalyst particle for fractional-order reactions. AIChE J 34:1916–1918

Szukiewicz M, Chmiel-Szukiewicz E, Kaczmarski K, Szałek A (2019) Dead zone for hydrogenation of propylene reaction carried out on commercial catalyst pellets. Open Chem 17:295–301. https://doi.org/10.1515/chem-2019-0037)

Perry RH, Green DW, Maloney JO (1997) Perry’s chemical engineers’ handbook, 7th edn. McGraw-Hill, New York

Funding

This study was funded by the National Science Center, Poland (Grant Number 2015/17/B/ST8/03369).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Szukiewicz, M.K. Study of reaction–diffusion problem: modeling, exact analytical solution, and experimental verification. SN Appl. Sci. 2, 1253 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-020-3045-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-020-3045-0