Abstract

The application of superabsorbent polymer hydrogels is gaining much research attention. Industrial applications include agriculture, environmental engineering, biomedical and tissue engineering, oilfield, construction and electrical products, personal care products, and wastewater treatment. In this study, the swelling performance and adsorption kinetics of two commercial superabsorbent polymer hydrogels were evaluated based upon their stimuli response to pH and salinity at varying temperature and reaction time periods. Characterisation and evaluation of the materials were performed using analytical techniques—optical microscopy, scanning electron microscopy, thermal gravimetric analysis, and the gravimetric method. Experimental results show that reaction conditions strongly influence the swelling performance of the superabsorbent polymer hydrogels considered in this study. Generally, increasing pH and salinity concentration led to a significant decline in the swelling performance of both superabsorbent polymer hydrogels. An optimal temperature range between 50 and 75 °C was considered appropriate based on swell tests performed between 25 c to 100 °C over 2-, 4- and 6-h time periods. These findings serve as a guideline for material technologist and field engineers in the use of superabsorbent polymer hydrogels for a wide range of applications. The study results provide evidence that the two superabsorbent polymer hydrogels can be used for petroleum fraction-saline water emulsions separation, among other applications.

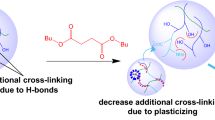

Graphic abstract

Highlights

-

The swelling performance of the two superabsorbent polymer hydrogels experimentally studied showed a maximum absorbency in the range of 270 to 300g/g.

-

Thermal gravimetric analysis curves show that both superabsorbent polymer hydrogels are stable at high temperatures.

-

Commercially available superabsorbent polymer hydrogels can be used in industrial water absorption applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Superabsorbent polymer hydrogels (SPHs) are a unique set of swellable polymeric materials. Due to their three-dimensional crosslinked polymeric network structure, SPHs can absorb disproportionately large quantities of different activation fluids and swell based upon their specific chemical crosslinks comprised of both hydrogen and ionic bonds. Their hydrophilic functional groups are responsible for their superabsorbent nature which does not lead to dissolution but rather result in formation of an insoluble gel. As a result of their versatility and suitability, SPHs have increasingly been used in a wide range of applications over the past decades as summarised in Table 1 [1].

Hydrogel materials have been the focus of considerable research due to their high hydrophilicity, low toxicity, and biocompatibility [4,5,6]. Studies have shown that several factors determine the application suitability of hydrogels including its swelling performance (particularly swelling rate), equilibrium swollen ratio, and mechanical strength from a dry to highly swollen state [4]. The swellability of the hydrogel is dependent on its response mechanism to external stimuli such as pH, salt concentration, temperature, and ionisation and to its chemical composition and backbone monomer type [7,8,9,10,11]. Slow temperature response rate and low mechanical strength have been identified as common disadvantages of hydrogels [12]. Several techniques have been adopted to modify hydrogels to increase their suitability for various applications, for example crosslinking with nanoparticles [13, 14] and copolymerisation [15].

Lenji et al. [16] carried out a series of experiments to investigate the swelling and rheological behaviour of preformed particle gel (PPG) made up of polyacrylamide and aluminium nitrate nanohydrate for potential application in water shutoff treatment in oil and gas reservoirs. This specific class of PPG functions as a superabsorbent and absorbs water equivalent in weight to 1000–2000 times its dry weight. The study investigated the effects of polymer and crosslinker concentrations, temperature, salinity, and pH on the swelling performance of the PPG. It was observed that the PPG swelling ratio declined with an increase in the polymer and crosslinker concentrations and salinity. Conversely, an increase in the polymer and crosslinker concentration enhanced the PPG strength. Regarding pH, acidic conditions below 5 or basic conditions of above 9 generally lowered the swelling ratio with a favourable ratio in the range of 5–9 being identified. High temperature above 100 °C, usually results in a collapse of the PPG 3-D network structure leading to a decline in its swelling ratio. A reduction of between 30 and 65% in water effluents was observed from the waterflood experiments aimed at testing the blocking efficiency of the PPG in reducing water production.

Namazi et al. [17] synthesised oxidised starch hydrogels impregnated with ZnO nanoparticles and evaluated its swelling performance by varying pH and salinity. The swelling performance of the nanocomposite hydrogels show sensitivity to pH with the maximum swelling observed at pH 7; however, this decreased with an increase in the salt concentration.

Singh and Dhaliwal [18] studied the morphological characteristics and swelling behaviour of silver nanoparticles containing superabsorbent polymer under varying pH and temperature conditions with respect to time. Findings on the morphologies of the materials showed irregular surfaces which is suggested to cause high swelling ratios due to the diffusion of water through the surface. Sensitivity of the polymer under varying conditions shows that it exhibits maximum swelling capacity of 1700% in neutral medium at 50 °C after 15 h. The study concluded that this class of superabsorbent has potential applications for water absorption purposes.

Natkanski et al. [19] synthesised a class of novel composites by introducing polyacrylic acid or polyacrylates hydrogels into montmorillonite via in situ polymerisation technique. Different analytic approaches were used to study the structure and composition of the samples with the results showing that the monomer type has a strong influence on the location of a polymer chain in the formed composite. It was also reported that the position of the monomer determined the swelling and adsorption properties with the pH influencing the kinetics of Fe(III) cation adsorption.

Al-Anbakey [20] and Alonso et al. [21] investigated the effect of pH and temperature on the swelling performance of different hydrogels and both agreed that the pH of the activation fluid is a strong determinant of their swelling performance. Meanwhile, Alonso et al. [21] reported the thermal response of the hydrogels tested and stated that the hydrogels were sensitive to the temperature condition with the highest swelling capacity found at pH 7 at 30 °C. Similar investigations for pH sensitivity were carried out by Kim et al. [4] with mechanical properties included in the analysis. The hydrogels used for the study were impregnated with polystyrene nanoparticles by free radical polymerisation in the presence of a crosslinking agent of different concentrations. The results showed that the hydrogel crosslinked to the least extent with a high amount of polystyrene, exhibited the fast-swelling rates, highest equilibrium swelling ratios and pH sensitivity. It was also observed that incorporating fillers by copolymerisation to enhance the mechanical property of the equilibrium swelling hydrogel was more effective when compared with the crosslinking degree.

Zareie et al. [22] modified a hydrogel network with silica nanoparticles to improve its mechanical and thermal stability while reducing its viscosity. To demonstrate the improved properties of the polyacrylamide hydrogel and its suitability for use in the oil industry, several testing methods were applied. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) imaging was used to observe the morphological polymer matrix, the dispersion and distribution of the silica nanoparticles and filler within the hydrogel network. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) was used to analyse the bonds formed by the chemical structure of the prepared hydrogel. The bottle test method was conducted to evaluate the hydrogel gelation time while viscosity measurements were taken at different shear rates to investigate the effect of the silica nanoparticles on gellant fluidity. Hydrogel strength was investigated using the elastic modulus in the range of 1–1000% strain. Finally, they compared the swelling behaviour of the hydrogels under different conditions. El-hoshoudy et al. [23] synthesised polyacrylate hydrogels and also conducted sandpack flooding experiments. Characterisation of the 2-(hexadecyloxy) ethyl methacrylate surfmer was performed using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), which evaluated the decomposition profile of the hydrogel sample while proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) was conducted to confirm the complete polymerisation of the monomers along with the absence of different chemical shifts. Viscoelasticity of the hydrogel was evaluated through measurements of shearing moduli which involves elastic moduli and viscous moduli, the application of a sinusoid oscillating shear strain. The swelling behaviour of the hydrogel samples were tested with different concentrations of polyethylene glycol (PEG) solutions. Gel strength was estimated qualitatively using the Sydansk’s gel strength code by monitoring the appearance of the gel structure on the wall of the inverted ampoule at different time intervals. The shear thinning behaviour of the hydrogel was tested through viscosity measurements where the viscosity-shear stress behaviour of samples was evaluated at various shear rates at 25 °C. The effect of salinity and electrolytic resistance was assessed through estimation of the hydrogel viscosity in different saline solutions at 25 °C and at a shear rate of 7.34 s−1. Thermal aging tests were performed by placing the hydrogel samples in an electrolyte solution of total dissolved solids of 40,000 ppm for 7 days under different temperatures of 25, 50, 75, and 90 °C after which the viscosity-shear rate profiles were recorded. Tang et al. [24] designed, synthesised and characterised a thermo-sensitive hydrogels, tri-copolymer poly(N-tert-butyl acrylamide-co-N-isopropyl acrylamide-co-acrylamide). SEM was used to observe the interior network morphologies and microscopy of the freeze-dried hydrogels. FTIR was used to determine the functional groups present and the extent of polymerisation. Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) tests were performed to determine the effect of network components on the glass transition temperature (Tg). The swelling and deswelling behaviour of the temperature-responsive hydrogels were studied to determine its swelling kinetics as a result of crosslink density. Compression tests of the hydrogels were performed for different crosslinker concentrations.

In summary, up to date studies have investigated the effects of hydrogel composition (mainly monomer, crosslinker, and initiator concentrations) and operating conditions such as temperature, salinity and pH on hydrogel strength and swelling performance. In most studies [25,26,27,28], synthesis of the hydrogels has been through polymerisation of acrylicamide free radicals while in other studies, the polymerisation process has adopted some commercial polymer superabsorbents such as LiquiBlock 40 K and Daqing (DQ) with the chemical composition of polyacrylic acid and polyacrylamide. However, very few studies have focused on the specific application of different SPHs for use in medium- to high-temperature industrial processes.

In this study, therefore, a detailed investigation has been performed on two commercially available SPHs: (1) poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt, and (2) sodium polyacrylate. While previous studies have focused on synthesised swellable polymers for specified applications, this study is focused on a set of relatively cheap and commercially available polymers. The commercial polymers have been chosen because they are readily available and can be applied with limited or no further modifications/synthesis for the operating conditions tested in this study. Testing conditions were chosen for temperature (25–100 °C), pH (6.5–12) and salinity (0–85,000 ppm) based on typical operating conditions experienced within refinery separation operations and sandstone reservoirs. The pH value of most oilfield water is between 4 and 9. The superabsorbent property of these two crosslinked swellable materials was characterised using various analytical techniques including optical microscopy, scanning electron microscopy, thermal gravimetric analysis, and the gravimetric method. In addition to conforming to standard testing protocols derived from literature [22,23,24], the characterisation of the poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt and sodium polyacrylate was based on their transient stimuli response to pH, salinity concentration, temperature and reaction time periods (Fig. 1).

2 Experiments

2.1 Materials

The SPHs used in this study were poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt and sodium polyacrylate and were both acquired from a major materials supplier and were tested without any further modification. As seen from Fig. 2, both superabsorbent materials are white in appearance with high angularity and irregular shapes.

Poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt and sodium polyacrylate are both superabsorbent crosslinked polymers having a density of 0.54 g/mL at 25 °C [25, 26]. Figure 3 shows the repeating terms of the chemical structures of both poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt and sodium polyacrylate used in this study. Both SPHs absorb many times its weight of aqueous fluids to produce gels which retain fluids under stress and do not dissolve.

Deionised water was obtained from an 18 Ω Milli-Q Integral ultrapure water system. Sodium chloride of ≥ 99% purity was acquired from Sigma-Aldrich and used along with deionised water to prepare brine solutions of varying concentrations (0, 35,000 and 85,000 ppm). 1 M sodium hydroxide solution was used to alter the pH of deionised water at appropriately 21 °C.

2.2 Characterisation

Samples of the superabsorbent materials were lightly scattered on microscope slides to be characterised according to their equivalent diameter (the diameter of a circle with the equivalent area) using an optical microscope fitted with a camera and open-source ImageJ analysis software. Under the same optical condition, an image of a linear scale was used for calibration.

A Zeiss EVO LS10 variable pressure scanning electron microscope (SEM), operating at an acceleration voltage of 25 kV, was used to investigate the surface morphology of dry and swollen samples of the superabsorbent materials. The superabsorbent materials in both dry and swollen states were electrically conductive and therefore were not sputter coated with gold or gold/palladium alloy. Hence, the swollen superabsorbent samples were mounted on SEM stubs and placed under vacuum before observation. Surface morphologies were imaged at magnifications of 75 × and 6000 ×.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed on the two SPH samples to determine their degradation and decomposition temperature as well as the rate of degradation using a TA TGA Q500. This analysis was performed by measuring the weight variation of one of the given samples due to temperature increase and phase change as the sample degrades until it is decomposed. The thermal stability was measured by using the ramp mode setting from room temperature (21 °C) to 800 °C at a rate of 10 °C per minute under a nitrogen environment. About 5–8 mg of dry sample was tested on a platinum pan and the sample weight loss analysed as a function of temperature.

2.3 Evaluation of gelation strength (bottle test method)

The bottle test method is an experimental technique which provides a semi-quantitative measurement to study gelation kinetics without applying stress or shear. The Sydansk’s method [22, 23, 29,30,31] employed offers insight into gelation time and strength, thermal stability and syneresis time using an alphabetical code to describe the behaviour of the gels upon bottle inversion (Table 2). In these experiments, 1 g of the polymer samples was added to 100 mL of deionised water in a thermally resistant sealed glass bottle at 90 °C. In this study, this method was used to determine gelation strength.

2.4 Swelling measurement

The swelling behaviour of the superabsorbent samples were performed using the gravimetric approach to characterise the polymer networks under different conditions. For a typical measurement, 1 g of the superabsorbent polymer sample was weighed (m0) then immersed in the different activation fluids (400 mL). Free swelling was allowed to take place for specific time periods of 2-, 4- and 6-h, and then the residual activation fluid was separated in the beaker from the swollen superabsorbent material using Grade 3, 6 µm filter paper. The solvent absorption or swelling ratio (W) was calculated by measuring the mass gained by the swollen sample. Runs were carried out at various temperatures of 25 °C, 50 °C, 75 °C and 100 °C. The swelling ratio was calculated using Eq. 1, where mt is the superabsorbent material mass at time (t) and mo represents the weight of the dry sample before free swelling [32].

Salt sensitivity factor of an electrolyte solution was also computed using Eq. 2, [14, 25].

where S and Se represent polymer swelling ratios in deionised water and in the electrolyte solution, respectively.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Morphology study

Figure 4 provides photographic images of poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt and sodium polyacrylate superabsorbent polymer hydrogel particles in both their dry and swollen states.

The particle size ranges of poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt and sodium polyacrylate were determined by microscopy to be in the range of 100–250 μm and 300–700 μm respectively. When viewed using an optical microscope in transmitted light, the SPHs appear as rough, angular shaped granules. Lee et al. [33] attributes this type of surface texture and shape to the grinding process after solution polymerisation at their manufacturing stage. Figure 5a–d shows their particle sizes, surface textures, particle shapes and their corresponding particle size distribution.

SEM micrographs were used to clarify the shape of the microporous polymer network structures and are displayed in Fig. 6. It follows that SEM is generally used appropriately to study the interior network morphologies [24]. At the 2 µm scale, the morphological structure of the two samples are significantly different with more surface roughness and porous voids observed in the sodium polyacrylate sample as compared to the poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt. However, the cross-sectional nanomorphology of both SPHs exhibited a neat, uniform and clear exterior morphology with regularly distributed pore spaces as a result of the conventional crosslinking polymerisation.

The number and size of pore spaces can be attributed to the method used to dry the SPHs; this is a critical factor in their morphological development. SPHs prepared by freeze-drying swell significantly more when compared to others which are air-dried [34]. From the micrographs, the poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt seems to be less porous having a narrower pore-size distribution than the sodium polyacrylate. The difference in pore size distribution may explain the difference in swelling performances of the two polymers.

3.2 Evaluation of gelation strength

The gel strength was determined based on the Sydansk’s hydrogel strength code as presented in Table 2. By monitoring the appearance of the gel structure on the wall of the inverted thermal resistant glass bottles at varying time intervals (see Fig. 7), the hydrogel strength codes of E and I with viscosity limitations of 5–6 and 11–13 Pa.s, were arrived at for the poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt and sodium polyacrylate samples, respectively at 90 °C. This indicated that the SPH materials exhibit reasonable gel strength and stability. This was similar to Lashari et al. [31] who reported gelation codes of E to G by varying the concentration of SiO2 of their novel composite polymer gel and also Zareie et al. [22] who recorded a gelation strength code of H for their polyacrylamide hydrogel impregnated with silica nanoparticles.

3.3 Thermal degradation

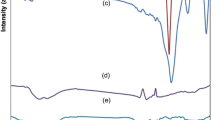

A thermal degradation study provides a good indicator of the ability of superabsorbent material to survive high temperature conditions [35]. For this reason, TG curves of the poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt and sodium polyacrylate were obtained from their dry, initial weights of 5.78 g and 7.79 g, respectively (Fig. 8). For both samples, minor weight loss was observed at temperatures less than 250 °C. The weight loss curve of both samples indicated three-stages of thermal decomposition: for the poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt sample, these regions are 25–281 °C, 281–430 °C and 430–619 °C while for the sodium polyacrylate these regions are 25–360 °C, 360–477 °C and 477–592 °C.

The first stage of decomposition is associated with the loss of water adsorbed on the surface of the particles also known as bound water. Decomposition profiles of the poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt and sodium polyacrylate samples showed their structural water loss (19% and 14%, equivalent to their remaining weights of 4.66 g and 6.72 g) between 31 and 281 °C and 26–360 °C, respectively. The second stage of decomposition is related to the intermolecular dehydration reactions and some initial depolymerisation reactions; the maximum weight loss occurred at this stage of decomposition for both samples. For the poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt sample this occurred between 281 and 430 °C with a weight loss of approximately 33% and remaining weight of 2.82 g. Similarly, between 360 and 477 °C, a reduced weight of 4.27 g was recorded with a corresponding weight loss of 32% for the sodium polyacrylate sample. The third stage of decomposition is attributed to depolymerisation reactions and the breaking of the crosslinks between the different polymeric chains. For the poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt, this occurred between 430 and 619 °C with a loss of 77% with a reduced weight of 1.31 g while for the sodium polyacrylate it occurred between 477 and 592 °C with a weight loss of 88% and reduced weight of 3.25 g. The final degradation stage of both samples was observed at between 620 and 800 °C and 592–800 °C for the poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt and sodium polyacrylate, respectively. At the maximum temperature of 800 °C, the residue of poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt and sodium polyacrylate was 20 and 40%, with residual weights of 1.18 g and 3.07 g respectively; this indicated a high amount of reticulation of both sample matrixes.

The TG curve of pyrolysis of the poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt and sodium polyacrylate takes place prominently in the temperature range of 281–620 °C and 360–592 °C, respectively. High temperature stability is an important property for medium- to high-temperature industrial processes because many of the organic polymers commonly used thermally decompose above 120 °C [36]. The TG curve of the poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt and sodium polyacrylate suggests that the polymers have good thermal stability suitable for a typical reservoir temperature between 90 and 150 °C with a loss in polymer mass of 0.4–1.5% and 2.2–5.4% respectively.

3.4 Sensitivity of particle swelling ratio to various thermochemical conditions

3.4.1 Effect of temperature

Temperature is an important factor affecting the absorbency capacity of SPHs [35, 37] and in this study different swelling behaviours were observed for the two superabsorbent materials tested.

After 2-h of free swelling, the absorbency of the poly (acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt decreased with increasing temperature with the peak absorbency occurring at 25 °C whereas and the lowest at 100 °C (Fig. 9a). At 25 °C, the polymer network formed hydrogen bonds with the water molecules, developing a hydration shell around the hydrophilic group which enhanced water uptake capacity to a maximum absorbency (285 g/g). However, with increasing temperature, the absorbency steadily decreased due to the elasticity of the cross-linked polymer network leading to the release of absorbed water. The collapse of the hydration shell at high temperature, 100 °C, may be responsible for the decrease in absorbency capacity (264 g/g). The polymer 3D network structure collapses due to destabilisation of the polymer network structure with increasing hydrolysis temperature leading to syneresis. In the case of the sodium polyacrylate, there was no noticeable trend in the swelling behaviour; swelling performance decreased from 25 to 50 °C and later peaked at 75 °C (280 g/g).

As seen on Fig. 9b, after 4-h of free swelling the poly (acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt experienced a notably sharp decrease in its absorbency (246 g/g) at 50 °C. Conversely, the sodium polyacrylate showed a steady increase in absorbency (290 g/g) at 50 °C and thereafter a sloping decrease in absorbency (239 g/g) at 100 °C, as its polymer network collapsed leading to a release of its absorbed water.

As shown in Fig. 9c, after 6-h of free swelling the poly (acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt experienced its peak absorbency (294 g/g) at 50 °C and lowest (204 g/g) at 100 °C. While the sodium polyacrylate exhibited a similar swelling behaviour, at 25 °C it demonstrated its highest absorbency (293 g/g) which decreased (264 g/g) at 50 °C. For both samples at 75 °C and higher, their polymer networks collapsed significantly leading to a release of absorbed water.

Different investigators have reported the optimal temperatures for different hydrogel samples tested. For example, Singh and Dhaliwal [18] have reported 50 °C and Alonso et al. [21] have reported 30 °C; the optimal temperature range of the hydrogels in this study was evaluated to be between 50 and 75 °C.

3.4.2 Effect of pH

SPHs exhibit dramatic volume transition in response to chemical stimuli such as pH [5]. Therefore, the swelling performance of the SPHs based on their pH sensitivity was measured under varying pH conditions ranging from 6.5 to 12 with an accuracy of ± 0.2.

As illustrated on Fig. 10, the swelling behaviour of the poly (acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt and sodium acrylate typically demonstrate maximum swelling between pH 6.5 (neutral medium) and 9 after free swelling at 25 °C for 2-, 4- and 6-h. This observation is in agreement with Lenji et al. [25] and Alonso et al. [21] who also observe that the optimal range for the hydrogels was at a temperature of about 30 °C, between pH 7 and 9. Figure 10a–c reflects the transient behaviour of the SPHs, with the highest swelling performance being observed at pH 9 after 2 h of free swelling. This systematically shifted to pH 6.5 after 4- and 6-h periods. This phenomenological change is due to the abundant of –COO− group which reduces the hydrogen bonding interactions.

The swelling behaviour of both samples may be further explained using the osmotic pressure (\( \pi_{ion} \)) ion theory [38, 39] where the osmotic swelling pressure for a weakly charged hydrogel network is given by:

Here, \( C_{i}^{g} \) and \( C_{i}^{s} \) are the molar concentration of the mobile ions in the swollen sample and ions present in the activation fluid, respectively and R and T, the gas constant and absolute temperature, respectively. In neutral aqueous activation fluids, the concentration of moveable ions (\( C_{i}^{s} \)) is very small, which is responsible for the higher value of \( \pi_{ion} \). In basic activation fluids, the concentrations of Na+ and OH− ions are very high and this reduces the values of \( \pi_{ion} \).

3.4.3 Effect of salinity concentration

The swelling performance of the superabsorbent polymers are strongly influenced by the ionic strength of the environment [5, 25]. The relationship between salt concentration and the swelling performance of the superabsorbent materials, in sodium chloride (NaCl) salt solutions (0, 35,000 and 85,000 ppm) are presented in Fig. 11. As observed for both cases of SPHs, their swelling capacity substantially diminishes with an increase in NaCl concentration. This result is in harmony with Sun et al. [40] and Singh and Dhaliwal [18] who reported a rapid decrease in hydrogel adsorption due to the increasing amount of Na+ metal ion concentration of the solutions. This phenomenological occurrence can be attributed to the effect of the additional cations which cause a decrease in anion–anion electrostatic repulsion, resulting in a decrease in the osmotic pressure difference between the polymer networks and the external solution. The difference in mobile ion concentration between the polymer networks and liquid phases decreases resulting in a decrease in absorbency capacity.

Table 3 shows the sensitivity of the SPH samples to NaCl salt of varying concentration, calculated using Eq. 3 above. Results show that the salt sensitivity factor for both SPHs increases with increasing salinity. It is also observed that the salt sensitivity factor decreases with increasing operating temperature at constant conditions. Though the sensitivity of the two SPH samples vary slightly, the same trend is seen for both the poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt and sodium polyacrylate samples.

3.5 Swelling kinetics

Understanding the swelling kinetics of SPHs is important for their operational use, especially for specific use in water production scenarios, because their swelling performance is directly affected by their adsorption properties [40]. To explain the swelling mechanism of the investigated SPHs, the Schott second-order dynamic model [40, 41] presented in Eq. 4 was used to analyse the experimental data.

where St is the absolute cumulative water penetrating the polymer network at time t and k2 is the second order rate constant for water absorption processes. On integrating the above equation within the limits t = 0, St = 0 and t = ∞, S = S∞, the following equation is obtained:

where A = 1 / k2, with k2 being the initial swelling rate of the hydrogel; B = 1 / S∞, with S∞ being the theoretical equilibrium swelling ratio of the hydrogel.

Thus, the Schott kinetic rate constant of swelling, k2, can be calculated as

The effect of time on the swelling performance is illustrated in Fig. 12. As shown in Table 4, the R2 value of the Schott second-order dynamic fitting curve is 0.9848 and 0.9925 for the poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt and sodium polyacrylate, respectively. This indicates that the swelling process does appropriately fit the Schott second-order dynamic equation. Comparable results were seen by Sun et al. [40, 42] who calculated R2 values greater than 0.98 for their calculated kinetic parameters.

4 Conclusion

This study experimentally evaluated the swelling performance of two SPHs, poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt and sodium polyacrylate, based on their stimuli response to pH, salinity concentration, temperature and reaction time periods. Several important conclusions have emerged:

-

The swelling behaviour of the granular SPHs tested were significantly influenced by the characteristics of the absorbing solutions (pH and ionic concentrations). Maximum swelling of both hydrogels occurred between pH 6.5 and 9 after free swelling at 25 °C for 2 h but systematically shifts to pH 6.5 after 4- and 6-h periods which may be attributed to the abundant –COO − group which reduces the hydrogen bonding interactions. An increase in NaCl concentration substantially decreased the swelling capacity of both hydrogels due to the effect of the additional cations which cause a decrease in anion–anion electrostatic repulsion, decreasing the osmotic pressure difference between the polymer networks and the external solution.

-

TGA results revealed that both SPHs are thermally stable and can thus be used under elevated temperate conditions. Initial decomposition of the poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt and sodium polyacrylate samples were between 31 and 281 °C and 26–360 °C with weight losses of 19% and 14% respectively due to structural water loss.

-

Generally, the absorbency of the SPHs decreases with increasing temperature. The collapse of the hydration shell at high temperatures may be responsible for the decrease in the absorbency capacity of the hydrogels. An optimal temperature range of between 50 and 75 °C was considered appropriate based on the swell test performed between 25 and 100 °C over 2-, 4- and 6-h time periods.

The results from this study conclusively demonstrate that both poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt and sodium polyacrylate are promising materials which can be implemented in a wide range of industrial applications.

Our research in this area is important to expand present understanding of these materials and their application boundaries in various technical applications. In particular, these findings form the basis for optimising commercially available SPHs which can be tuned to desired characteristic behaviours for functional applications in (i) conformance/water control operations, (ii) enhanced/improved oil recovery operations, and (iii) in separation processes for petroleum fraction-saline water emulsions.

Data availability

The raw/processed data required to reproduce these findings cannot be shared at this time as the data also forms part of an ongoing study.

Change history

28 July 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-021-04654-w

Abbreviations

- W:

-

Swelling ratio

- mt :

-

Superabsorbent material mass at time, t

- mo :

-

Original superabsorbent material mass

- f:

-

Salt sensitivity factor

- S:

-

Polymer swelling ratio in deionised water

- Se :

-

Polymer swelling ratio in electrolyte solution

- \( {\uppi}_{\text{ion}} \) :

-

Osmotic pressure

- \( {\text{C}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{g}} \) :

-

Molar concentration of mobile ions in swollen sample

- \( {\text{C}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{s}} \) :

-

Molar concentration of ions in the activation fluid

- R:

-

Gas constant

- T:

-

Absolute temperature

- St :

-

Absolute cumulative water penetrated by the polymer network at time, t

- k2 :

-

Second order rate constant for water absorption processes

- S∞ :

-

Theoretical equilibrium swelling ratio of hydrogel

- A, B:

-

Empirical coefficient

- t:

-

Time

References

Ganji F, Vasheghani-Farahani S, Vasheghani-Farahani E (2010) Theoretical description of hydrogel swelling: a review. Iran Polym J 19(5):375–398

Zohuriaan-Mehr MJ, Omidian H, Doroudiani S, Kabiri K (2010) Advances in non-hygienic applications of superabsorbent hydrogel materials. J Mater Sci 45:5711–5735

Zohuriaan-Mehr MJ, Kabiri K (2008) Superabsorbent polymer materials: a review. Iran Polym J 17(6):451–477

Kim B, Hong D, Chang WV (2013) Swelling and mechanical properties of pH-sensitive hydrogel filled with polystyrene nanoparticles. J Appl Polym Sci 130:3574–3587

Ahmed EM (2015) Hydrogel: preparation, characterization, and applications: a review. J Adv Res 6:105–121

Zhao C, Shengqiang N, Min T, Shudong S (2011) Polymeric pH-sensitive membranes—a review. Prog Polym Sci 36(11):1499–1520

Qiu Y, Kinam P (2001) Environment-sensitive hydrogels for drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 53:321–339

Lowe T, Elina V, Heikki T (1998) Dynamic light scattering studies on polyelectrolytic derivatives of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide). Polymer 39(3):641–650

Schild HG, David AT (1990) Sodium 2-(N-Dodecylamino)naphthalene-6-sulfonate as a probe of polymer-surfactant interaction. Langmuir 6(11):1676–1679

Feil H, Bae Y, Feijen J, Kim S (1992) Mutual influence of pH and temperature on the swelling of ionizable and thermosensitive hydrogels. Macromolecules 25(20):5528–5530

Feil H, Bae Y, Jan F, Sung WK (1993) Effects of comonomer hydrophilicity and ionization on the lower critical solution temperature of N-isopropylacrylamide copolymers. Macromolecules 26:2496–2500

Li P, Hou X, Qu L, Dai X, Zhang C (2018) PNIPAM-MAPOSS hybrid hydrogels with excellent swelling behavior and enhanced mechanical performance: preparation and drug release of 5-Fluorouracil. Polymers 10:137

Li P, Kim N, Hui D, Rhee K, Lee J (2009) Improved mechanical and swelling behavior of the composite hydrogels prepared by ionic monomer and acid-activated Laponite. Appl Clay Sci 46:414–417

Aalaie J, Ebrahim V-F, Ali R, Mohammad AS (2008) Effect of montmorillonite on gelation and swelling behavior of sulfonated polyacrylamide nanocomposite hydrogels in electrolyte solutions. Eur Polymer J 44:2024–2031

Li L, Du X, Deng J, Yang W (2011) Synthesis of optically active macroporous poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) hydrogels with helical poly(N-propargylamide) for chiral recognition of amino acids. React Funct Polym 71:972–979

Lenji MA, Masoud H, Mohsen VS, Mahsa BS, Aghdas H (2018) Experimental study of swelling and rheological behavior of preformed particle gel used in water shutoff treatment. J Petrol Sci Eng 169:739–747

Namazi H, Hasani M, Yadollahi M (2019) Antibacterial oxidized starch/ZnO nanocomposite hydrogel: synthesis and evaluation of its swelling behaviours in various pHs and salt solutions. Int J Biol Macromol 126:578–584

Singh J, Dhaliwal A (2018) Synthesis, characterization and swelling behavior of silver nanoparticlescontaining superabsorbent based on grafted copolymer of polyacrylic acid/Guar gum. Vacuum 157:51–60

Natkanski P, Piotr K, Anna B, Zofia P, Marek M (2012) Controlled swelling and adsorption properties of polyacrylate/montmorillonite composites. Mater Chem Phys 136:1109–1115

Al-Anbakey A (2014) Effect of pH on swelling properties of commercial polyacrylic acid hydrogel bead. J Atoms Mol 4(1):656–665

Alonso GJ, José LRA, Ana MMM, Maria LMH (2007) Effect of temperature and pH on swelling behavior of hydroxyethyl cellullose-acrylamide hydrogel. e-Polymers. https://doi.org/10.1515/epoly.2007.7.1.1744

Zareie C, Bahramian AR, Sefti MV, Salehi MB (2019) Network-gel strength relationship and performance improvement of polyacrylamide hydrogel using nano-silica; with regards to application in oil wells conditions. J Mol Liq 278:512–520

El-hoshoudy A, Mohammedy MM, Ramzi M, Desouky SM, Attia AM (2019) Experimental, modeling and simulation investigations of a novel surfmer-co-poly acrylates crosslinked hydrogels for water shut-off and improved oil recovery. J Mol Liq 277:142–156

Tang L, Gong L, Zhou G, Liu L, Zhang D, Tang J, Zheng J (2019) Design of low temperature-responsive hydrogels used as a temperature indicator. Polymers 173:182–189

Lenji MA, Haghshenasfard M, Sefti MV, Salehi MB (2018) Experimental study of swelling and rheological behavior of preformed particle gel used in water shutoff treatment. J Pet Sci Eng 169:739–747

Bai B, Zhang H (2011) Preformed particle gel transport through open fracture and its effect on water flow. Soc Petrol Eng J 16(02):388–400

Elsharafi MO, Baojun B (2012) Effect of weak preformed particle gel on unswept oil zones/areas during conformance control treatments. Ind Eng Chem Res 51(35):11547–11554

Elsharafi MO, Baojun B (2016) Effect of back pressure on the gel pack permeability in mature reservoir. Fuel 183:449–456

Sydansk R, Argabright PA (1987) Conformance improvement in a subterranean hydrocarbon bearing formation using a cross-linked polymer. U.S. Patent 4683949

Tessarolli FGC, Souza STS, Gomes AS, Mansur CRE (2019) Gelation kinetics of hydrogels based on acrylamide–AMPS–NVP terpolymer, bentonite, and polyethylenimine for conformance control of oil reservoirs. Gels 5(1):1–23

Lashari ZA, Yang H, Zhu Z, Tang X, Cao C, Iqbal MW, Kang W (2018) Experimental research of high strength thermally stable organic composite polymer gel. J Mol Liq 263:118–124

Ali SL, Majid K, Javed R, Murtaza S, Muhammad SK, Abbas K, Mohib U (2018) Superabsorbent polymer hydrogels with good thermal and mechanical properties for removal of selected heavy metal ions. J Clean Prod 201:78–87

Lee HX, Wong HS, Buenfeld NR (2018) Effect of alkalinity and calcium concentration of pore solution on the swelling and ionic exchange of superabsorbent polymers in cement paste. Cement Concrete Compos 88:150–164

Patel VR, Mansoor MA (1996) Preparation and characterization of freeze-dried chitosan-poly(ethylene oxide) hydrogels for site-specific antibiotic delivery in the stomach. Pharm Res 13(4):588–593

Salehi MB, Asefe MM, Samira ZM (2019) Polyacrylamide hydrogel application in sand control with compressive strength testing. Pet Sci 16(1):94–104

Kosynkin DV, Gabriel C, Kurt CW, Jay RL, Jason TS, Arvind DP, James EF, James MT (2012) Graphene oxide as a high-performance fluid-loss-control additive in water-based drilling fluids. Appl Mater Interfaces 4(1):222–227

He H, Yefei W, Xiaojie S, Peng Z, Dandan L (2015) Development and evaluation of organic/inorganic combined gel for conformance control in high temperature and high salinity reservoirs. J Pet Explor Prod Technol 5(2):211–217

Horkay F, Ichiji T, Peter JB (1999) Osmotic swelling of polyacrylate hydrogels in physiological salt solutions. Biomacromol 1(1):84–90

Mittal H, Jindal R, Kaith B, Maity A, Ray S (2015) Flocculation and adsorption properties of biodegradable gum-ghatti-grafted poly(acrylamide-co-methacrylic acid) hydrogels. Carbohyd Polym 115:617–628

Sun X-F, Yiwei H, Yingyue C, Qihang Z (2019) Superadsorbent hydrogel based on lignin and montmorillonite for Cu(II) ions removal from aqueous solution. Int J Biol Macromol 124:511–519

Huang Y, Baoping Z, Gewen X, Wentao H (2013) Swelling behaviours and mechanical properties of silk fibroin–polyurethane composite hydrogels. Compos Sci Technol 84:15–22

Sun X, Jing ZWG (2012) Preparation and swelling behaviors of porous hemicellulose-g-polyacrylamide hydrogels. J Appl Polym Sci 128(3):1861–1870

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the School of Engineering at Robert Gordon University in conducting this investigation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article has been revised: The names of the polymers and their applications have been removed.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahon, R., Balogun, Y., Oluyemi, G. et al. Swelling performance of sodium polyacrylate and poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) potassium salt. SN Appl. Sci. 2, 117 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1874-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1874-5