Abstract

Family-based therapy is a common front-line strategy to prevent child maltreatment in high-risk families. This review aimed to systematically assess the evidence of the effect of family-based therapy programs on child maltreatment outcomes. CINAHL, Scopus and PsycINFO were systematically searched to March 25, 2023. Outcome data were extracted for child protection reports and out-of-home care (OOHC) placements from administrative data, and parent- or child-reported maltreatment risk. 12 RCTs and two observational studies of 8,410 screened were included. All 14 studies had high risk of bias. Sample sizes ranged from 43 in an RCT to 3875 families in an observational study. In seven studies with child protection report risk estimates, five studies (3 RCTs, 2 observational) showed results in favor of the intervention (risk differences (RD) of 2.0–41.1 percentage points) and two RCTs in favor of the comparison (RD, 2.0–8.6 percentage points). In the four studies with OOHC risk estimates, three studies (2 RCTs, 1 observational) showed results in favor of the intervention (RD, 0.9–17.4 percentage points) and one observational study showed results in favor of the comparison (RD, 1.5 percentage points). Most studies had ≤ 100 participants, did not estimate main causal effects, and had high risk of bias. Thus, although family-based therapy programs may reduce child maltreatment, the high risk of bias, typically small sample sizes (> 62% of studies had sample sizes < 100), and inconsistent results across studies means it is currently unclear whether family-based therapy interventions achieve better child maltreatment outcomes, compared with usual care services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The numbers of children in out-of-home care (OOHC) due to maltreatment has risen in high-income countries (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare, 2021; Children’s Bureau, 2017; Department for Education, 2021) in recent decades. By age five, 1–6% of children have experienced ≥ 1 OOHC placement in Australia (Falster et al., 2021, Pilkington et al., 2019), Canada (O’Donnell et al., 2016) and the United States (US) (Putnam-Hornstein et al., 2013) with 2–3% of children by age 18 years in the US (Wildeman & Emanuel, 2014) and New Zealand (Rouland & Vaithianathan, 2018). Supporting families to keep children safe at home is important for children, families, communities, and connection to culture (Davis, 2019). There is substantial policy interest in interventions to support high-risk families to keep their children safe at home, driven by the imperative to protect vulnerable children and to reduce the numbers of children in OOHC, which is extremely costly for governments (Australia Productivity Commission, 2018; Broadhurst & Mason, 2013).

First adapted for child maltreatment in the 1980s (Alternative for Families: A Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, n.d.; Brunk et al., 1987) family-based therapy interventions are one of a suite of frontline services provided to families at high risk of physical abuse and neglect. Family-based therapy is broad in definition, with the main distinction from individual-based therapy being that it treats the family unit as a system, which may include parents, extended family and children (Carr, 2000; Pardeck, 1989; Skuse et al., 2017). In child protection, family-based therapy involves psychologists or social workers who engage with family members to modify home environments, behaviors and interaction patterns of parents and children, with the goal of reducing physical abuse and/or neglect so children can safely remain or reunify with their family (Carr, 2009, 2019; Pardeck, 1989).

Most family-based therapy programs for child maltreatment were developed in the US and are now implemented internationally (Carr, 2019). Investment in such programs is not insubstantial. For example, estimated program costs per family range from 16,000–22,000USD for Multisystemic Therapy for Child Abuse and Neglect (MST-CAN) (Swenson et al., 2010) in the US (Dopp et al., 2018) and Functional Family Therapy – Child Welfare (FFT-CW®) (Alexander et al., 2011) in Australia (Shakeshaft et al., 2021). The extent to which these programs are effective at reducing maltreatment and child protection contacts is of significant policy interest because of the imperative to improve child outcomes, as well as the substantial costs associated with program investment and OOHC (Australia Productivity Commission, 2018; Broadhurst & Mason, 2013).

Given there is no published evidence synthesis on the effectiveness of a suite of family-based therapies for child maltreatment outcomes, this review was motivated to inform government decision making about the potential outcomes that may result from investment in these interventions. In this study, we conducted a narrative systematic review of the evidence on the effect of family-based therapy programs on reducing physical abuse and neglect among high-risk or maltreated children. We focused on the policy-relevant outcomes of child protection reports and OOHC placements, and parent- and child-reported maltreatment risk.

Methods

This review was undertaken according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Moher et al., 2009) and registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic reviews (PROSPERO).

Study inclusion criteria

Study designs

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomized observational published and unpublished studies in English if they: included a parallel cohort as a comparison group (i.e., groups observed at the same points in time); aimed to estimate the effect of family-based therapy interventions on physical abuse or neglect; and met the following criteria laid out under sub-headers below (more details in Appendix 1).

Population

Families with an assessment of high risk, or substantiated physical abuse or neglect, for ≥ 1 children aged 0–17 years. Studies of families with substantiated sexual abuse only were excluded.

Intervention

Family-based therapy interventions that aimed to reduce physical abuse and/or neglect among high-risk families, which may have been delivered as a component of licenced programs, including: family preservation, parenting and community-based programs; home support and case management services (more details in Appendix 2). Family-based therapy is a broad definition, which we operationalized as follows: a psychological or sociological family therapy component (e.g., systemic family therapy) was described in the treatment protocol; therapy was delivered by qualified health professionals including psychologists, social workers and/or counsellors; and multiple family members (e.g., parents and children), participated in family therapy sessions.

Comparators

Usual care services for families at high risk of maltreatment including, but not limited to: parenting programs, psychoeducation, case management, home support and visitation, behavioural and emotional regulation workshops, or waitlist.

Outcomes

Policy-relevant outcomes of maltreatment included: (i) child protection reports of alleged maltreatment to child protection agencies; and (ii) OOHC placements, including placement of a child in care outside the family home by a child protection agency. Parent- and/or child-reported measures of maltreatment risk or experience were also included.

Search strategy

CINAHL, Scopus and PsycINFO were systematically searched for studies prior to the most recent search date (March 25, 2023). The three electronic database searches included unpublished research consisting of thesis dissertations, government, committee and research reports, conference abstracts, news articles, factsheets and statistical datasets. Manual searches of forward and backward citations of studies selected for review were also conducted. Appendix 3 summarizes the search strategy, which included search terms: family therapy, therapy, intervention, child-parent relations, high-risk families, risk factors, vulnerable populations, child abuse, child neglect, child abuse and physical abuse for CINAHL, and family therapy, child abuse and child neglect for Scopus and PsycINFO.

Study selection

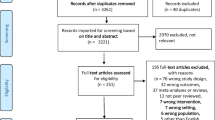

Two authors screened the titles/abstracts and full texts of 8410 articles for eligibility after removing duplicates. After every 100 titles/abstracts screened, the small number of discrepancies (3% abstracts, 2% full texts) were resolved with two additional co-authors.

Data extraction

Information was systematically extracted on: author, year, country, study design, sample size, family therapy program, program duration, comparator, study period, loss-to-follow up, participant demographics, substantiated abuse/neglect history, participating family members, intervention setting, and therapist qualifications.

For child protection reports and OOHC placement outcomes, we extracted the absolute risk, mean days and placement changes in the intervention and comparison group and measures of effect for between-group comparisons of post-treatment outcomes, where reported. For parent and child-reported measures of maltreatment risk, we extracted the mean scores in each group, mean differences and standardized measures of effect (i.e., Cohen’s d) for between-group comparisons of post-treatment outcomes (see Appendix 4), which summarize the magnitude of the absolute difference relative to the standard deviation of the outcome (Maxwell, 2004). We did not extract the within-group comparisons of pre- and post-treatment outcomes reported in some studies because between-group comparisons are necessary to estimate causal effects (Bland & Altman, 2015).

Risk of bias assessments

We used the Cochrane Risk-of-Bias tool for randomized trials (RoB) 2 (Sterne et al., 2019) to assess risk of bias in RCTs as low, moderate or high on five domains, and overall. The Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies – of Interventions (ROBINS-I) assessment tool (Sterne et al., 2016) was used to assess risk of bias in observational studies as low, moderate, serious or critical on seven domains, and overall. Three authors assessed the risk of bias with input from co-authors.

Synthesis of results

We conducted a narrative synthesis of results. We concluded it was not meaningful, and in most cases not possible, to quantitatively synthesize the results in a meta-analysis for several reasons. Family-based therapy was often delivered as part of complex, sustained programs and the interventions varied across studies. No RCTs reported a main causal effect of the intervention by calculating the absolute or relative risk difference in post-treatment outcomes between the intervention and comparison groups. Some studies did not report numerators and/or denominators for post-treatment outcomes and/or confidence intervals. We calculated crude risk differences as the closest estimate of an Intention-to-Treat (ITT) effect using post-treatment absolute risks; however, we were unable and/or did not calculate standard errors/confidence intervals for the causal contrast because of small study samples or adjust for differences in pre-treatment prognostic factors. Cluster RCTs were analysed at the identical ‘level’ as the clustered allocation, meaning each participant was treated as if they were their own cluster. Although the two non-randomized observational studies reported odds ratios and standard errors for child protection reports and OOHC outcomes, one study did not include all participants or adjust for confounding.

We calculated the fragility index (Walsh et al., 2014) for the child protection report and OOHC outcomes in studies reporting statistically significant results (i.e., p < 0.05) (Kane, 2018). The fragility index is a summary of the impact of small sample sizes on effects. It estimates the number of additional families in the smaller group that would be required to have the event to obtain a non-significant result (i.e., p > 0.05).

Because most studies did not estimate a main causal effect of the intervention or report standard errors, we could not assess publication bias using funnel plots.

Results

Study selection

Database searches identified 7550 studies and manual reference and citation searches identified 1648 articles (Fig. 1). Fourteen studies published in English met inclusion criteria; 12 RCTs (including one cluster RCT) and two non-randomized observational studies. Study participants had a substantiated maltreatment history in 10/14 studies (physical abuse in 3, neglect in 1, both in 6) and therapists had relevant tertiary qualifications in 11/14 studies; however, these inclusion criteria were not reported in all studies (Appendix 5).

Study characteristics

RCTs

Findings from eleven RCTs in the US and one in Australia were published between 1996 and 2021, including 9/12 since 2010 (Table 1). Average study sample size was 99 families, ranging from 44–195. Intervention and comparison groups included 18 vs. 12 families in the smallest RCT and 122 vs. 73 families in the largest RCT. Study follow-up ranged from 0 days to 24 months after completing treatment. Interventions were delivered in the home (4/12) and/or clinic or community settings (10/12) for 12–34 weeks. Comparison group families received usual care services or an alternative program (Table 1, Appendix 2).

Non-randomized observational studies

Two non-randomized observational studies were conducted in the US in 2013 and 2017. One study included 43 families (25 intervention, 18 usual care) to examine the effectiveness of the Multisystemic Therapy – Building Stronger Families (MST-BSF) program versus Comprehensive Community Treatment. The other study included 3875 families (1625 intervention, 2250 usual care) to examine the Functional Family Therapy – Child Welfare (FFT-CW®) program versus usual care. Both interventions were delivered in the home for 6–9 months, with study follow-up between 7–18 months post-treatment.

Risk of bias

Risk of bias for RCTs

All RCTs had a high overall risk of bias using the ROB-2 (Sterne et al., 2019) (Fig. 2). There were some concerns about the randomization process in all RCTs, mostly because allocation sequence concealment or pre-treatment characteristics were not reported, or pre-treatment prognostic factors differed between groups. All but one RCT (Runyon et al., 2010) had a high risk of bias on domain two, largely because blinding participants to the intervention was not possible and main causal effects were not reported for all outcomes. Risk of bias due to missing child protection service outcome data was low (Kolko, 1996; Schaeffer et al., 2021; Swenson et al., 2010) and high (Chaffin et al., 2004, 2011; Kolko et al., 2018) in three RCTs apiece. Risk of bias due to missing self-reported outcome data was low in five RCTs (Foley et al., 2016; Kolko, 1996; Schaeffer et al., 2021; Swenson et al., 2010; Villodas et al., 2021) and high in five RCTs (Donohue et al., 2014; Kolko et al., 2018; Meezan & O’Keefe, 1998; Runyon et al., 2010; Thomas & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2011). There were no sensitivity analyses on the impact of selection bias due to missing outcome data. Risk of bias for measurement of child protection report/OOHC outcomes was low in the six RCTs reporting these outcomes (Chaffin et al., 2004, 2011; Kolko, 1996; Kolko et al., 2018; Schaeffer et al., 2021; Swenson et al., 2010). In the ten RCTs reporting self-reported outcome measures (Donohue et al., 2014; Foley et al., 2016; Kolko, 1996; Kolko et al., 2018; Meezan & O’Keefe, 1998; Runyon et al., 2010; Schaeffer et al., 2021; Swenson et al., 2010; Thomas & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2011; Villodas et al., 2021), five had high risk of bias because blinding outcome assessors to treatment allocation was not possible and/or not clearly reported (Foley et al., 2016; Meezan & O’Keefe, 1998; Schaeffer et al., 2021; Swenson et al., 2010; Thomas & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2011). None of the RCTs reported pre-specified protocols resulting in some concerns about the potential for selected reporting.

Risk of bias for observational studies

The overall risk of bias was high in both observational studies (Fig. 3) (Schaeffer et al., 2013; Turner et al., 2017). Lack of reporting on loss to follow-up, missing outcome data and pre-specified protocols were issues. There was also concern about bias due to confounding in the analysis of child protection report outcomes in one study (Turner et al., 2017).

Child protection report outcomes

Six RCTs (Chaffin et al., 2004, 2011; Kolko, 1996; Kolko et al., 2018; Schaeffer et al., 2021; Swenson et al., 2010) and two observational studies (Schaeffer et al., 2013; Turner et al., 2017) examined child protection report outcomes using child protection service data.

RCTs

The post-treatment risk of ≥ 1 child protection reports were extracted for the intervention and comparison groups in 5/6 RCTs (Chaffin et al., 2004; Kolko, 1996; Kolko et al., 2018; Schaeffer et al., 2021; Swenson et al., 2010), which we used to calculate risk differences as a policy-relevant measure of the ITT effect (Table 2). In three RCTs (Chaffin et al., 2004; Kolko, 1996; Swenson et al., 2010), risk differences were in favor of the intervention group, ranging from -7.4 to –30.0 percentage points in the 8–24 months after completing the intervention (Table 2). In two RCTs (Kolko et al., 2018; Schaeffer et al., 2021), there was a risk difference of 2.0 and 8.6 percentage points in favor of the comparison group. Fragility indexes for the four RCTs ranged from 0 to 3. This means that if up to 3 families had experienced the opposite outcome to the one recorded, the finding of a statistically significant effect (at p < 0.05) would have become non-significant.

In the remaining RCT (Chaffin et al., 2011), it was not possible to calculate the risk difference for child protection reports or fragility indexes. The authors in this study reported the numerator (for reports) and denominator for the entire study sample (58/153, 38%), but did not report numerators and denominators for the intervention (i.e., PCIT) or usual care groups, which are necessary to estimate the main causal effect of PCIT versus usual care.

Observational studies

The child protection report risk was lower in the intervention group than the comparison group, with risk differences of -2 and –41.1 percentage points and fragility indexes of 2 and 6 in the two observational studies (Table 2) (Schaeffer et al., 2013; Turner et al., 2017). One study reported an adjusted odds ratio of 5.01 (95% CI, 1.03–24.32) based on a sample of 43 families: 5/25 families (20%) in the intervention group, and 11/18 families (61.1%) in the comparison group had ≥ 1 reports (Schaeffer et al., 2013).

Out-of-home care placement outcomes

Three RCTs (Chaffin et al., 2011; Schaeffer et al., 2021; Swenson et al., 2010) and two observational studies (Schaeffer et al., 2013; Turner et al., 2017) reported OOHC placement outcomes.

RCTs

The absolute risk of ≥ 1 OOHC placement in the intervention and comparison groups were extracted for 2/3 RCTs (Table 3) (Schaeffer et al., 2021; Swenson et al., 2010). The risk difference was –0.9 and –17.4 percentage points in favor of the intervention group (Table 3). In the other RCT (Chaffin et al., 2011), it was not possible to calculate the risk difference for OOHC placement because the authors only reported the numerator (for OOHC) and denominator for the entire study sample (58/153, 38%) rather than the intervention and comparison groups. Three RCTs (Donohue et al., 2014; Schaeffer et al., 2021; Swenson et al., 2010) reported mean days in OOHC in each group, with between group differences ranging from 8.6 to –36.4 days in the 10–18 months post-baseline follow-up (Appendix 6). One RCT (Swenson et al., 2010) reported placement changes in OOHC in each group, with a between group difference of –0.51 changes in the 16-months of post-baseline follow-up (Appendix 7).

Observational studies

In a study of 43 families (Schaeffer et al., 2013), there was a risk difference of -15.8 percentage points in favor of the intervention group and fragility index of 2 (Table 3). The authors reported an adjusted odds ratio of 3.12 (SE = 1.13) for the between group comparison of OOHC placement risk, as well as a difference of –44.4 mean days in OOHC (Appendix 6) and –0.5 placement changes (Appendix 7) in the 24-months post-baseline (Schaeffer et al., 2013). In a study of 3875 families (Turner et al., 2017), OOHC placement risk was higher in the intervention group compared to usual care, with a risk difference of 1.5 percentage points and fragility index of 9.

Parent- and child-reported measures of physical abuse and neglect risk/experience

Although eleven included studies (10 RCTs: Donohue et al., 2014; Foley et al., 2016; Kolko, 1996; Kolko et al., 2018; Meezan & O’Keefe, 1998; Runyon et al., 2010; Schaeffer et al., 2021; Swenson et al., 2010; Thomas & Zimmer-Gembeck; Villodas et al., 2021, 1 observational: Schaeffer et al., 2013)) administered parent or child-reported measures of maltreatment risk (Tables 4 & 5, Appendix 8), standardized pooled measures of effect for between-group differences were only reported in 3 RCTs (Table 4) (Runyon et al., 2010; Thomas & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2011; Villodas et al., 2021). One RCT of 75 families reported moderate benefits of family-based therapy on the incidence of physical abuse (d = 0.47), with the reverse association observed using the parent-reported measure (d = -0.57) (Runyon et al., 2010). A second RCT of 55 families reported a small beneficial effect of family-based therapy on the parent-reported measure (d = -0.13) (Villodas et al., 2021) whereas a third RCT of 150 families showed a marginally beneficial effect of usual care on the risk of abuse and neglect (d = 0.08) (Thomas & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2011).

In seven RCTs (Donohue et al., 2014; Foley et al., 2016; Kolko, 1996; Kolko et al., 2018; Meezan & O’Keefe, 1998; Schaeffer et al., 2021; Swenson et al., 2010) and one observational study (Schaeffer et al., 2013), the authors reported within-group differences pre- and post- intervention for three measures and/or their relevant subscales (Table 5, Appendix 8).

Discussion

Summary of evidence

We systematically reviewed 12 RCTs and two non-randomized observational studies of family-based therapy programs for families with high risk or substantiated maltreatment, published between 1996 and 2021. The sample sizes of RCTs ranged from 44 to 195 families. The overall risk of bias was high in all studies, which was, in part, due to inherent challenges in recruitment and retention of families and outcome measurement in high-risk populations. However, there are opportunities to strengthen approaches to minimising bias and interpreting its impact when reporting study findings in child maltreatment intervention research. Evidence from three RCTs (Chaffin et al., 2004; Kolko, 1996; Swenson et al., 2010) and one observational study (Schaeffer et al., 2013) suggest family-based therapies may reduce the recurrence of physical abuse or neglect, compared with usual care up to 24-months post-treatment. In contrast, two RCTs (Kolko et al., 2018; Schaeffer et al., 2021) and one observational study (Turner et al., 2017) found a lower risk of child protection reports and OOHC placements in families receiving usual care, compared with family-based therapy. Fragility index calculations show that the statistical significance of the findings from all RCTs may have reversed if ≤ 3 children in the intervention or comparison group had experienced a different outcome to the one recorded. Although family-based therapy may have benefits for vulnerable families, studies published to date do not provide consistent, low biased evidence on whether family-based therapy reduces physical abuse or neglect among high-risk families, compared with usual care services. Our finding is similar to another recent systematic review that found mixed evidence of program efficacy across outcomes within and between RCTs published to date for Multisystemic Therapy programs (MST) that aim to improve child and adolescent behavioral, psychosocial and psychiatric outcomes (Littell et al., 2021).

Of the reviewed RCTs, the least biased evidence of the effect of a family-based therapy intervention on maltreatment outcomes comes from an RCT of 87 families randomized to Multisystemic Therapy for Child Abuse and Neglect (MST-CAN) or Enhanced Outpatient Therapy in the USA in 2010 (Swenson et al., 2010). In this study, results showed the MST-CAN program reduced the risk of child protection reports by 7.4% (based on 2/44 families in the intervention and 5/42 families in the comparison group) and OOHC placements by 17.4% (based on 6/44 families in the intervention and 13/42 families in the comparison group) within approximately eight months of completing treatment. However, the results were fragile due to the small sample size. There was also a high overall risk of bias when considering the reported child protection and parent- and child-reported outcomes.

Of the observational studies, the Turner et al. (2017) study recruited 3875 families in the USA, which was the largest sample size of included studies in this review. Turner et al. (2017) reported the absolute risks of child protection reports and OOHC placements for children in the Functional Family Therapy – Child Welfare (FFT-CW®) and the usual care groups, within strata of several confounding factors, such as parental substance abuse and mental health. Beyond this descriptive analysis, the reported odds ratios (0.788 for child protection reports; 1.36 for OOHC) did not appear to be adjusted for multiple confounders, which is necessary to estimate unbiased program effects in observational studies. Our crude risk difference estimates suggest only small absolute differences in child protection report and OOHC outcomes between the FFT-CW and usual care groups (-2 and 1.5 percentage points, respectively). In contrast, the other observational study of 43 families in the US who received Multisystemic Therapy – Building Stronger Families (MST-BSF), or usual care, had a comparatively lower risk of bias, including > 90% ascertainment of study outcomes and adjustment for multiple confounders (Schaeffer et al., 2013). Although the Schaeffer et al. (2013) findings suggest MST-BSF may reduce the risk of child protection reports by 41.1% (based on 5/25 families in the intervention and 11/18 families in the comparison group) and OOHC placements by 15.8% (based on 3/25 families in the intervention and 5/18 families in the comparison group) in the 24-months since baseline, we found that the results were extremely fragile due to small numbers.

Strengths

This systematic review examined the effect of family-based therapies on the policy-relevant outcomes of child protection reports and OOHC placements. We reviewed 14 studies in accordance with PRISMA and Cochrane guidelines (Moher et al., 2009). We used the RoB 2 (Sterne et al., 2019) and ROBINS-I (Sterne et al., 2016) tools to assess the risk of bias, which were developed for studies examining the efficacy and effectiveness of clinical and pharmacological interventions, respectively. Although the same potential sources of bias are relevant when evaluating the effect of interventions for child maltreatment, it may be challenging to overcome some biases in studies of complex, sustained interventions for vulnerable families. For example, retention of vulnerable families in treatment and outcome measure collection are common challenges. It is also unrealistic to blind participants and therapists to treatment allocation, which is common in RCTs of pharmacological interventions.

Limitations

Limitations of the review

Risk of bias of reviewed studies was undertaken as per Cochrane guidelines (Moher et al., 2009). Such assessments can be difficult when the necessary information is not reported. Although the overall risk of bias was high, we included all studies in this review to comprehensively summarize what is known to date about programs using family therapy in this evolving, interdisciplinary research field. It was not meaningful (and for most studies, not possible) to quantitatively synthesize the evidence because of the methodological and reporting limitations in the original studies. Many of these methodological limitations relate to the challenges of evaluating complex, sustained child maltreatment interventions with vulnerable families. Thus, we focused on realistic opportunities to improve the design and reporting of studies of health or child welfare sector interventions.

Limitations of the included studies

Pre-treatment factors prognostic of the outcome were not reported for each group in all studies, which is key to assessing bias related to randomization as outlined by Cochrane (Higgins et al., 2019). Some studies based decisions about treatment group comparability on statistically significant differences in pre-treatment risk factors (i.e., p-values < 0.05). Health and medical research reporting guidelines (Montgomery et al., 2018; Vandenbroucke et al., 2007) now strongly discourage the use of p-values for this purpose, instead recommending that sample size, size and variability of the difference, and the strength of association between pre-treatment prognostic factors and outcomes are considered.

Three studies did not report missing outcome data. Although outcome data were reported missing for up to 23% (administrative data outcomes) and 69% (parent- and child-reported measures) of participants in other studies, none reported pre-treatment characteristics between families with and without missing outcome data to assess the potential impact of selection bias.

While between-group comparisons of post-treatment outcomes are necessary to estimate causal effects, several studies only reported within-group pre- and post-treatment outcomes. Within-group comparisons do not compare the intervention group with a group that is similar on pre-treatment risk factors, and while potentially informative, they do not allow conclusions to be drawn about the real-world impacts of interventions (Bland & Altman, 2015).

In RCTs that examined child protection report and OOHC outcomes, the absolute risks were reported, but not an estimate of the main causal effect of the intervention, such as absolute and relative risk difference measures between the intervention and comparison groups. Where possible, we calculated crude risk differences as the best possible estimate of a causal effect; however, we were unable to adjust for differences in pre-treatment risk factors or generate confidence intervals because information to calculate standard errors was not reported. Although one observational study adjusted for measured confounders (Schaeffer et al., 2013) the other observational study did not adjust for measured confounders, despite baseline differences between groups (Turner et al., 2017).

None of the RCTs referred to a publicly available, pre-specified analysis plan (i.e., published prior to the trial), which is now standard practice for clinical trials in health and medical research (Grant et al., 2018). This may in part be due to half of the RCTs being published on or before the publication of the CONSORT-2010 guidelines (Schulz et al., 2010).

Implications for policy and practice

Current evidence of program efficacy or effectiveness

The current evidence examines the effects of family-based therapies on physical abuse or neglect in the 0 days to 24 months post-treatment (average follow-up 8-months post-treatment). Although family-based therapy programs may reduce child maltreatment in the short-term, the high risk of bias and inconsistent findings across studies means it is currently unclear whether family-based therapy programs achieve better child maltreatment outcomes, compared with usual care, in the settings and populations studied to date. Given most studies were conducted in the United States, the effect of family-based therapy programs in other settings and populations is under-studied, including among Indigenous populations who are often over-represented in child protection systems, such as Australia (Davis, 2019), Canada (O’Donnell et al., 2016) and New Zealand (Rouland et al., 2019).

Methodological challenges in evaluating program efficacy and effectiveness

There are many challenges to conducting high quality intervention studies in the child maltreatment field, including recruitment of participants representative of the target population, adequate sample sizes, and retaining families to study completion. Family-based therapy programs are often complex, sustained interventions and treatment protocols may be less defined than clinical and pharmaco-epidemiology intervention studies, which makes treatment adherence difficult to assess. Moreover, it is not always clear to what extent the intervention and comparison treatments differ. In the case that family-based therapy program and comparison treatments are not substantially different in their structure and design, then it is reasonable to expect small or no beneficial effects of the intervention, compared with the comparison condition.

Retention of disadvantaged families in sustained family-based therapy interventions or usual care services is often challenging in the child protection context, as evidenced by the missing outcome data in the included studies. It is likely that participants with complete outcome data in the intervention and usual care groups were not representative of the whole target population for the included studies. Few studies included in this review reported the characteristics of participants with and without missing outcome data, which is best practice to facilitate assessment of the potential impact of selection bias on study findings.

Opportunities to leverage existing data to evaluate program effectiveness

To generate consistently high-quality evidence on the effect of family-based therapy interventions in local contexts and populations, adequate funding is needed to co-design evaluations with communities and service providers, to recruit and retain large appropriate sample sizes, and to develop protocols that minimize the risk of bias. As discussed, meeting the conditions to generate high-quality evidence from RCTs of family-based therapy can be challenging. One alternative to RCTs is to conduct cost-effective, large-scale, real-world interventions of program effectiveness by using quasi-experimental methods as part of emulating a trial using non-randomized observational study designs at scale (Hernán et al., 2008). This approach requires investing in routinely collected data on the type, timing and frequency of intervention delivery and linking this data to other whole-of-population health and human services administrative datasets for children and families. The resulting infrastructure can minimize bias from missing outcome data and enable longer-term evaluation of outcomes at low burden to children, families and service providers and at a relatively low cost, compared with conducting RCTs. Examples of using linked administrative data and observational study designs to estimate the effect of an intervention compared to usual care can be seen in the integration of nurse home-visiting program data with whole-of-population data from multiple agencies for children and families in South Australia (Moreno-Betancur et al., 2022), New Zealand (Vaithianathan et al., 2016) and Manitoba, Canada (Chartier et al., 2018).

Conclusions

Although family-based therapy programs may reduce child maltreatment, the high risk of bias and inconsistent findings across studies means it is unclear whether family-based therapy programs achieve better child maltreatment outcomes, compared with usual care. To understand whether investment in interventions achieve the intended outcomes for high-risk populations, adequate funding for high quality evidence is needed to guide policy decisions. In an era where data linkage capabilities have increased, there now exist opportunities to leverage routinely collected data on service delivery and outcomes to include larger sample sizes and emulate the target trial in observational study designs (Hernán & Robins, 2016), similar to comparative effectiveness studies of pharmacological interventions (Dagan et al., 2021; Dickerman et al., 2019) and secondary prevention programs in public health (Chartier et al., 2018; Moreno-Betancur et al., 2022).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Alexander, J. F., & Robbins, M. S. (2011). Clinical handbook of assessing and treating conduct problems in youth. Springer.

Alternative for Families: A Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (n.d.). History of the Model. http://www.afcbt.org/EvidenceBase/HistoryoftheModel

Australia Productivity Commission. (2018). Report on Government services 2018. https://www.pc.gov.au/research/ongoing/report-on-government-services/2018

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2021). Child protection Australia 2019-2020. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/c3b0e267-bd63-4b91-9ea6-9fa4d14c688c/aihw-cws-78.pdf.aspx?inline=true

Bland, J. M., & Altman, D. G. (2015). Best (but oft forgotten) practices: Testing for treatment effects in randomized trials by separate analyses of changes from baseline in each group is a misleading approach. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 102(5), 991–994.

Broadhurst, K., & Mason, C. (2013). Maternal outcasts: Raising the profile of women who are vulnerable to successive, compulsory removals of their children–a plea for preventative action. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 35(3), 291–304.

Brunk, M. A., Henggeler, S. W., & Whelan, J. P. (1987). Comparison of multisystemic therapy and parent training in the brief treatment of child abuse and neglect. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55(2), 171.

Carr, A. (2000). Evidence-based practice in family therapy and systemic consultation: Child-focused problems. Journal of Family Therapy, 22(1), 29–60.

Carr, A. (2009). The effectiveness of family therapy and systemic interventions for child -focused problems. Journal of Family Therapy, 31, 3–45.

Carr, A. (2019). Family therapy and systemic interventions for child-focused problems: The current evidence base. Journal of Family Therapy, 41(2), 153–213.

Chaffin, M., Funderburk, B., Bard, D., Valle, L. A., & Gurwitch, R. (2011). A combined motivation and parent–child interaction therapy package reduces child welfare recidivism in a randomized dismantling field trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(1), 84–95.

Chaffin, M., Silivosky, J. F., Funderburk, B., Valle, L. A., Brestan, E. V., Balachova, T., Jackson, S., Lensgraf, J., & Bonner, B. L. (2004). Parent-chiuld interaction therapy with physically abusive parents: efficacy for reducing future abuse reports. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(3), 500–510.

Chartier, M., Nickel, N. C., Chateau, D., Enns, J. E., Isaac, M. R., Katz, A., Sarkar, J., Burland, E., Taylor, C., & Brownell, M. (2018). Families first home visiting programme reduces population-level child health and social inequities. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 72(1), 47–53.

Children’s Bureau (2017). The AFCARS report (No. 24). https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/cb/afcarsreport24.pdf

Dagan, N., Barda, N., Kepten, E., Miron, O., Perchik, S., Katz, M., Hernán, M. A., Lipsitch, M., Reis, B., & Balicer, R. D. (2021). BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine in a nationwide mass vaccination setting. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(15), 1412–1423.

Davis, M. (2019). Family is culture: Independent review of Aboriginal children and young people in OOHC. https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2019-10/apo-nid267061.pdf

Department for Education (2021). Children looked after in England including adoption: 2020 to 2021. https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/children-looked-after-in-england-including-adoptions/2021

Dickerman, B. A., García-Albéniz, X., Logan, R. W., Denaxas, S., & Hernán, M. A. (2019). Avoidable flaws in observational analyses: An application to statins and cancer. Nature Medicine, 25(10), 1601–1606.

Donohue, B., Azrin, N. H., Bradshaw, K., Van Hasselt, V. B., Cross, C. L., Urgelles, J., Romero, V., Hill, H. H., & Allen, D. N. (2014). A controlled evaluation of family behaviour therapy in concurrent child neglect and drug abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(4), 706–720.

Dopp, A. R., Schaeffer, C. M., Swenson, C. C., & Powell, J. S. (2018). Economic impact of multisystemic therapy for child abuse and neglect. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 45(6), 876–887.

Falster, K., Hanly, M., Pilkington, R., Eades, S., Stewart, J., Jorm, L., & Lynch, J. (2020). Cumulative Incidence of Child Protection Services Involvement Before Age 5 Years in 153 670 Australian Children. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(10), 995–997.

Foley, K., McNeil, C. B., Norman, M., & Wallace, N. M. (2016). Effectiveness of group format parent-child interaction therapy compared to treatment as usual in a community outreach organization. Child & Family Behaviour Therapy, 38(4), 279–298.

Grant, S., Mayo-Wilson, E., Montgomery, P., Macdonald, G., Michie, S., Hopewell, S., & Moher, D. (2018). CONSORT-SPI 2018 explanation and elaboration: Guidance for reporting social and psychological intervention trials. Trials, 19(1), 1–18.

Hernán, M. A., Alonso, A., Logan, R., Grodstein, F., Michels, K. B., Stampfer, M. J., Willett, W. C., Manson, J. E., & Robins, J. M. (2008). Observational studies analyzed like randomized experiments: an application to postmenopausal hormone therapy and coronary heart disease. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.), 19(6), 766.

Hernán, M. A., & Robins, J. M. (2016). Using big data to emulate a target trial when a randomized trial is not available. American Journal of Epidemiology, 183(8), 758–764.

Higgins, J. P. T., Eldridge, S., & Li, T. (Eds.). (2019). Chapter 23: Including variants on randomised trials. In J. P. T. Higgins, J. Thomas, J. Chandler, M. Cumpston, T. Li, M. J. Page, & V. A. Welch (Eds.), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019). Cochrane, 2019. Available from http://training.cochrane.org/handbook

Kane, S.P. (2018). Fragility Index Calculator. ClinCalc. https://clincalc.com/Stats/FragilityIndex.aspx

Kolko, D. J. (1996). Individual cognitive behavioural treatment and family therapy for physically abused children and their offending parents: A comparison of clinical outcomes. Child Maltreatment., 1(4), 322–342.

Kolko, D. J., Herschell, A. D., Baumann, B. L., Hart, J. A., & Wisniewski, S. R. (2018). AF-CBT for families experiencing physical aggression or abuse served by the mental health or child welfare system: An effectiveness trial. Child Maltreatment, 23(4), 319–333.

Littell, J. H., Pigott, T. D., Nilsen, K. H., Green, S. J., & Montgomery, O. L. (2021). Multisystemic Therapy® for social, emotional, and behavioural problems in youth age 10 to 17: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 17(4), e1158.

Maxwell, S. E. (2004). The persistence of underpowered studies in psychological research: Causes, consequences, and remedies. Psychological Methods, 9(2), 147–163.

Meezan, W., & O’Keefe, M. (1998). Evaluating the effectiveness of multifamily group therapy in child abuse and neglect. Research on Social Work Practice, 8(3), 330–353.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., Prisma Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Plos Medicine, 6(7), e1000097.

Montgomery, P., Grant, S., Mayo-Wilson, E., Macdonald, G., Michie, S., Hopewell, S., & Moher, D. (2018). Reporting randomised trials of social and psychological interventions: The CONSORT-SPI 2018 Extension. Trials, 19(1), 1–14.

Moreno-Betancur, M., Lynch, J. W., Pilkington, R. M., Schuch, H. S., Gialamas, A., Sawyer, M. G., Chittleborough, C. R., Schurer, S., & Gurrin, L. C. (2022). Emulating a target trial of intensive nurse home visiting in the policy-relevant population using linked administrative data. International Journal of Epidemiology, 52(1), 119–131.

O’Donnell, M., Maclean, M., Sims, S., Brownell, M., Ekuma, O., & Gilbert, R. (2016). Entering out-of-home care during childhood: Cumulative incidence study in Canada and Australia. Child Abuse & Neglect, 59, 78–87.

Pardeck, J. T. (1989). Family therapy as a treatment approach to child abuse. Family Therapy: The Journal of the California Graduate School of Family Psychology, 16(2), 113–120.

Pilkington, R., Montgomerie, A., Grant, J., Gialamas, A., Malvaso, C., Smithers, L., ... & Lynch, J. (2019). An innovative linked data platform to improve the wellbeing of children—the South Australian Early Childhood Data Project. Australia’s Welfare. Australia’s Welfare Series No. 14. Cat. No. AUS 226. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/75c9f692-c72c-438d-b68b-91318f780154/Australias-Welfare-Chapter-8-summary-18Sept2019.pdf.aspx

Putnam-Hornstein, E., Needell, B., King, B., & Johnson-Motoyama, M. (2013). Racial and ethnic disparities: A population-based examination of risk factors for involvement with child protective services. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(1), 33–46.

Rouland, B., & Vaithianathan, R. (2018). Cumulative prevalence of maltreatment among New Zealand children. 1998–2015. American Journal of Public Health, 108, 511–513.

Rouland, B., Vaithianathan, R., Wilson, D., & Putnam-Hornstein, E. (2019). Ethnic disparities in childhood prevalence of maltreatment: Evidence from a New Zealand birth cohort. American Journal of Public Health, 109(9), 1255–1257.

Runyon, M. K., Deblinger, E., & Steer, R. A. (2010). Group cognitive behavioural treatment for parents and children at-risk for physical abuse: An initial study. Child & Family Behaviour Therapy, 32(3), 196–218.

Schaeffer, C. M., Swenson, C. C., Tuerk, E. H., & Henggeler, S. W. (2013). Comprehensive treatment for co-occurring child maltreatment and parental substance abuse: Outcomes from a 24-month pilot study of the MST-Building Stronger Families program. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37, 596–607.

Schaeffer, C. M., Swenson, C. C., & Powell, J. S. (2021). Multisystemic Therapy-Building Stronger Families (MST-BSF): Substance misuse, child neglect, and parenting outcomes from an 18-month randomized effectiveness trial. Child Abuse & Neglect, 122, 105379.

Schulz, K. F., Altman, D. G., & Moher, D. C. O. N. S. O. R. T. (2010). statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Annals of Internal Medicine., 152(11), 726–732.

Shakeshaft, A., Economidis, G., D’Este, C., Oldmeadow, C., Tran, D. A., Nalukwago, S., ... & Doran, C. (2020). The application of Functional Family Therapy-Child Welfare (FFT-CW®) and Multisystemic Therapy for Child Abuse and Neglect (MST-CAN) to NSW: an early evaluation of processes, outcomes and economics. NSW Government’s Their Futures Matter. https://www.nsw.gov.au/investment-approach-for-human-services

Skuse, D., Bruce, H., & Dowdney, L. (Eds.). (2017). Child psychology and psychiatry: Frameworks for clinical training and practice (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Sterne, J. A., Hernán, M. A., Reeves, B. C., Savović, J., Berkman, N. D., Viswanathan, M., Henry, D., Altman, D. G., Ansari, M. T., Boutron, I., Carpenter, J. R., Chan, A. W., Churchill, R., Deeks, J. J., Hróbjartsson, A., Kirkham, J., Jüni, P., Loke, Y. K., Pigott, T. D., ... & Higgins, J. P. T. (2016). ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ, 355, i4919.

Sterne, J. A. C., Savović, J., Page, M. J., Elbers, R. G., Blencowe, N. S., Boutron, I., Cates, C. J., Cheng, H. Y., Corbett, M. S., Eldridge, S. M., Emberson, J. R., Hernán, M. A., Hopewell, S., Hróbjartsson, A., Junqueira, D. R., Jüni, P., Kirkham, J. J., Lasserson, T., Li, T., ... & Higgins, J. P. T. (2019). RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ, 366, l4898.

Swenson, C., Schaeffer, C., Henggeler, S., Faldowski, R., & Mayhew, A. (2010). Multisystemic therapy for child abuse and neglect. Journal of Family Psychology, 24(4), 497–507.

Their Futures Matter (2018). Their Futures Matter: A new approach. Reform directions from the Independent Review in Out of Home Care in New South Wales. https://www.theirfuturesmatter.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/723606/Their-Futures-Matter-A-new-approach-Reform-directions-from-the-Independent-Review.pdf

Thomas, R., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2011). Accumulating evidence for parent–child interaction therapy in the prevention of child maltreatment. Child Development, 82(1), 177–192.

Turner, C. W., Robbins, M. S., Rowlands, S., & Weaver, L. R. (2017). Summary of comparison between FFT-CW® and Usual Care sample from Administration for Children’s Services. Child Abuse & Neglect, 69, 85–95.

Vaithianathan, R., Wilson, M., Maloney, T., & Baird, S. (2016). The Impact of the Family Start Home Visiting Programme on Outcomes for Mothers and Children – A Quasi-Experimental Study. https://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/evaluation/family-start-outcomes-study/family-start-impact-study-report.pdf

Vandenbroucke, J. P., von Elm, E., Altman, D. G., Gotzsche, P. C., Mulrow, C. D., Pocock, S. J., Poole, C., Schlesselman, J. J., & Egger, M. (2007). Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Medicine, 4(10), 1628–1655.

Villodas, M. T., Moses, J. O., Cromer, K. D., Mendez, L., Magariño, L. S., Villodas, F. M., & Bagner, D. M. (2021). Feasibility and promise of community providers implementing home-based parent-child interaction therapy for families investigated for child abuse: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Child Abuse & Neglect, 117, 105063.

Walsh, M., Srinathan, S. K., McAuley, D. F., Mrkobrada, M., Levine, O., Ribic, C., Molnar, A. O., Dattani, N. D., Burke, A., Guyatt, G., Thabane, L., Walter, S. D., Pogue, J., & Devereaux, P. J. (2014). The statistical significance of randomized controlled trial results is frequently fragile: A case for a Fragility Index. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(6), 622–628.

Wildeman, C., & Emanuel, N. (2014). Cumulative risks of foster care placement by age 18 for US children, 2000–2011. PLoS ONE, 9(3), e92785.

Wolfe, D. A., Sandler, J., & Kaufman, K. (1981). A competency-based parent training program for child abusers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 49(5), 633.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions Mr Economidis was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship via the University of New South Wales (UNSW), Sydney, Australia, and a Higher Degree Research scholarship from the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre (NDARC), UNSW. Rhiannon Pilkington is supported by an NHMRC Clinical Trials and Cohort Studies grant APP1187489. John Lynch was awarded a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Centre of Research Excellence (1099422). The other authors received no additional funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mr. Economidis conceptualized and designed the review, conducted the systematic review search, article screening, data extraction and risk-of-bias assessments, drafted the initial manuscript, and revised the manuscript. Dr. Falster contributed to the design of the review, supervised screening, data extraction and risk-of-bias assessments, supervised drafting of the initial manuscript, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. Ms. Powell contributed to article screening, data extraction, risk-of-bias assessments, and revision of the manuscript. Dr. Pilkington contributed to the design of the review, screening, data extraction, risk-of-bias assessments, and interpretation of the results, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Eades critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

A/Prof. Dobbins contributed statistical expertise to the interpretation and reporting of results, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. Prof. Shakeshaft conceptualized and designed the review, interpretation of the results and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. Prof. Lynch contributed to the design of the review, interpretation of the results, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study does not involve human participants.

Competing interests

Anthony Shakeshaft was the lead investigator on a competitive tender (FACS.17.266) awarded by the NSW Government Department of Family and Community Services (now Department of Communities and Justice) to evaluate the Functional Family Therapy – Child Welfare [FFT-CW®] and Multisystemic Therapy for Child Abuse and Neglect [MST-CAN®] programs in New South Wales, Australia (2018–2020). George Economidis was employed part-time at the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre as a Project Coordinator for the FFT-CW® and MST-CAN program evaluation from May 2018 to August 2020. The other authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Economidis, G., Pilkington, R., Lynch, J. et al. The effect of family-based therapy on child physical abuse and neglect: a narrative systematic review. Int. Journal on Child Malt. 6, 633–674 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42448-023-00170-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42448-023-00170-z