Abstract

Leiomyomas are benign tumors, mostly located in the uterus. The pelvic localization is quite rare, and it is associated with unusual growth patterns. It is important to make an adequate differential diagnosis between malignant and benign retroperitoneal neoplasm because treatment is different. When it is not possible to have a precise preoperative diagnosis, a laparoscopic or laparotomy surgical tumorectomy is often required. To obtain a certain diagnosis, the goal of surgery is ensuring the complete excision of neoplasms and preservation of urination, defecation, and sexual function. We report a rare case of a 58-year-old woman who underwent a laparoscopic tumorectomy for a pelvic retroperitoneal leiomyoma. The patient reported occasional episodes of dull pain in the pelvic region. Pelvic contrast CT scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a retroperitoneal solid mass in contiguity with the posterior wall of the uterine body-isthmus, to be referred to as a pedunculated uterine fibroma strictly posteriorly adherent to the sigma. She first underwent to explorative laparoscopy by a gynecologist who did not find any uterine mass. The patient was subsequently admitted to the department of general surgery and has done a second operative laparoscopy which highlighted the presence of an extra-peritoneal para-rectal mass which was completely excised. The histological examination of tumor indicated that it was a leiomyoma. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged in III post-operative day (POD).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Leiomyoma is a benign mesenchymal tumor arising from smooth muscle cells. Leiomyomas are the most common pelvic tumor, occurring in approximately 70% of women during the fourth and fifth decades of women’s life [1]. However, extra-uterine leiomyomas located in the retroperitoneum are rare; in literature, only 105 cases have been registered [2]. Neoformations located in the retroperitoneum are most frequently sarcomas [3]. Extraperitoneal leiomyomas occur rarely and with non-specific characteristics, so the diagnosis can be challenging and may lead to misdiagnosis [4]. Preoperative imaging is unable to distinguish benign from malignant retroperitoneal neoplasms, so histopathology remains the gold standard to obtain a certain diagnosis [5]. In this study, we report a case of a 58-year-old woman diagnosed with pelvic retroperitoneal leiomyoma, which was a common tumor located in a rare position.

Case Report

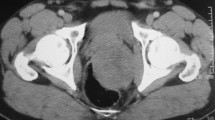

A 58-year-old nulliparous postmenopausal woman was admitted to our ER with acute and persistent abdominal and pelvic pain. The patient had a past medical history of arterial hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. She had no past familiar history of malignancies. The contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan showed in the pelvis an oval formation, with regular margins, measuring 57×40 mm, in contiguity with the posterior wall of the uterine body-isthmus, strictly suggestive for uterine fibroma. This neoplasm also came in contact with the sigmoid posteriorly (Fig. 1).

The patient underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) too which confirmed the solid formation documented on CT with a radiological finding of the pedunculated uterine fibroma (Fig. 2). Therefore, the patient was referred to the department of gynecology and after preoperative routine exams was planned explorative laparoscopy. During the procedure, it was not found either uterine fibroma or gynecological pathologies, but a retroperitoneal right mass apparently adherent to the sigma and rectum was observed. Intraoperative consulting by general surgeons was made indicating a second operative laparoscopic procedure in order to remove the mass for absence of informed consent too. Operative laparoscopy was performed 1 week later, and during surgical maneuvers, we confirm the intraoperative finding with medium size mass close to the sigma and rectum but mobile and apparently separated from it. The retroperitoneum was opened, and the tumor was gently removed in order to preserve the rectal wall and function. The measure of mass was about 6–8 cm, and it had a smooth, grayish-white surface and was completely excised (VIDEO). The final histological examination defined the neoformation as an extrauterine leiomyoma, with the following immunophenotype pattern: smooth muscle actin +, desmin +, cKit −, CD34−, S100−, EMA−. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged in III POD.

Discussion

Leiomyomas are smooth muscle benign tumors, rarely located in the retroperitoneum; the incidence of leiomyoma in the retroperitoneum is 1.2% [1]. In literature, we found only 105 cases of retroperitoneal leiomyomas. Although the retroperitoneum is a rare localization of leiomyoma, it is not the only one: extra-uterine leiomyoma can be found in the skin, in the respiratory system, or in the urinary system [6,7,8]. According to Billings et al. [9], there are two distinct subtypes: leiomyomas of somatic soft tissue and retroperitoneal–abdominal leiomyomas. The latter probably arise from hormonally sensitive smooth muscle; they present similar characteristics to intrauterine leiomyomas but at different sites, far from the uterus. They are likely independent soft tissue primaries rather than parasitic leiomyomas of the uterus [9]. The pathogenesis of retroperitoneal leiomyomas is still unknown. Some authors reported that pelvic retroperitoneal leiomyomas could arise from embryonal remnants of Mullerian or Wolffian tubes [10].

Clinically, patients with retroperitoneal leiomyoma report non-specific symptoms such as discomfort, fatigue, and back pain, although most are asymptomatic and the leiomyoma is diagnosed incidentally. Preoperative imaging methods (TC, MRI) recognize the location of the lesion, but it does not unequivocally distinguish between malignant and benign conditions [1, 2, 11]. Although MRI is the most accurate imaging modality for evaluating retroperitoneal masses, histopathology remains the gold standard for definitive diagnosis. Histologically, the tumor consists of intersecting fascicles of typical smooth muscle cells, with blunt-ended or slightly tapered nuclei, and the mitotic index is not high. The stroma contains numerous vessels with thick wall and mural hyalinization [9].

The gold standard treatment is surgical excision [12]. The principal goal is to resect completely the neoplasm and to preserve the integrity of the vessels and pelvic nerves. In literature, we found patients treated with a laparotomy, robot-assisted or laparoscopic approach, as in this case. In a previously reported case, a laparotomy was the most chosen option, although this approach would cause huge wounds and a long hospitalization [2]. The laparotomy approach is indicated when the tumor size is relatively large and there is adherence to adjacent structures, so a laparoscopic or robot-assisted approach could be difficult [2]. We decided for a laparoscopic approach because the tumor was relatively small and there were no adhesions with the pelvic organs on preoperative imaging.

Conclusions

Retroperitoneal leiomyoma of gynecologic type represents a challenging diagnosis. Histopathological examination remains the “gold standard” for making a definite diagnosis, and its role is crucial to distinguish it from other primary retroperitoneal tumors which are, in most of the cases, malignant.

Data Availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the supplementary material, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Poliquin V, Victory R, Vilos GA. Epidemiology, presentation, and management of retroperitoneal leiomyomata: systematic literature review and case report. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(2):152–60. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1553465007012186

Yüksel D, Kilic C, Kodal B, Cakir C, Güler Mesci C, Boran N, et al. A rare case of a retroperitoneal leiomyomatosis. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021;50(6):101760. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32325271

von Mehren M, Kane JM, Bui MM, Choy E, Connelly M, Dry S, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: soft tissue sarcoma, Version 1.2021. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2020;18(12):1604–12. https://jnccn.org/view/journals/jnccn/18/12/article-p1604.xml

Lin H-W, Su W-C, Tsai M-S, Cheong M-L. Pelvic retroperitoneal leiomyoma. Am J Surg. 2010;199(4):e36–8. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0002961009006291

Zhang Z, Shi F, She J. Robot-assisted tumorectomy for an unusual pelvic retroperitoneal leiomyoma: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101(31):e29650. https://journals.lww.com/10.1097/MD.0000000000029650

Niiyama S, Katsuoka K. Mobile leiomyoma of the skin. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23(4):567. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23985216

Zhang J, Dong A, Cui Y, Wang Y, Chen J. Diffuse cavitary benign metastasising leiomyoma of the lung. Thorax. 2019;74(2):208–9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30554139

Zachariou A, Filiponi M, Dimitriadis F, Kaltsas A, Sofikitis N. Transurethral resection of a bladder trigone leiomyoma: a rare case report. BMC Urol. 2020;20(1):152. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33028269

Billings SD, Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Do leiomyomas of deep soft tissue exist? Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25(9):1134–42. http://journals.lww.com/00000478-200109000-00003

Stutterecker D, Umek W, Tunn R, Sulzbacher I, Kainz C. Leiomyoma in the space of Retzius: a report of 2 cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185(1):248–9. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0002937801485097

Fasih N, Prasad Shanbhogue AK, Macdonald DB, Fraser-Hill MA, Papadatos D, Kielar AZ, et al. Leiomyomas beyond the uterus: unusual locations, rare manifestations. Radiographics. 2008;28(7):1931–48. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1900164

Miettinen M. Smooth muscle tumors of soft tissue and non-uterine viscera: biology and prognosis. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:S17–29. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S089339522203513X

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Roma La Sapienza within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation was performed by MP, data collection by MM, SMT, and AM, and the analysis by AFF, MDGP, and VG. CEV, MB, and FS supervised and critically revised the manuscript. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MP, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Procedures performed in the studies involving human participants were carried out in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

(MOV 332744 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pace, M., Moretti, M., Tierno, S.M. et al. Laparoscopic Tumorectomy for an Unusual Pelvic Retroperitoneal Leiomyoma: A Case Report. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 6, 7 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-023-01637-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-023-01637-3